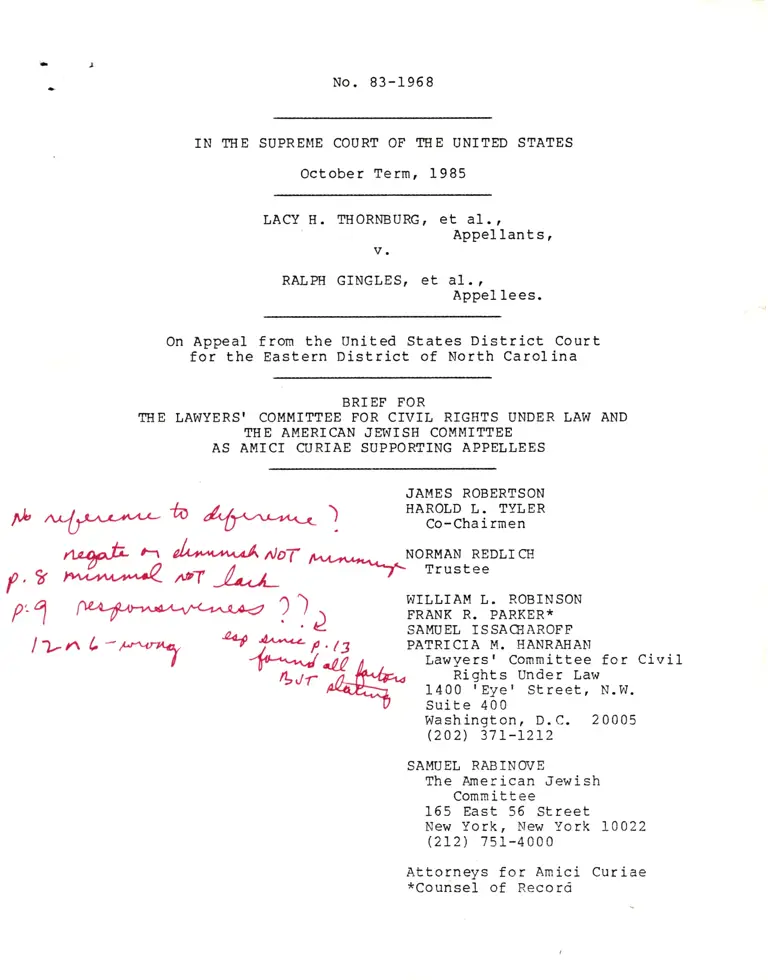

Annotated Draft Brief for Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights Under Law and Jewish Committee as Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1985

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Annotated Draft Brief for Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights Under Law and Jewish Committee as Amici Curiae, 1985. a2a07059-db92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b3853070-c6ca-4763-a4a9-c1a598313e76/annotated-draft-brief-for-lawyers-committee-for-civil-rights-under-law-and-jewish-committee-as-amici-curiae. Accessed January 31, 2026.

Copied!

IN

No. 83-1968

THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1985

LACY H. TIIORNBURG,

v.

RALPH GINGLESI €t

et dI. ,

Appel lant s ,

dI. t

Appel 1ees.

On Appeal from the

for the Eastern

United States District Court

District of North Carolina

BRTEF FOR

ITIE LAWYERSI COMMITTBE FOR CTVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW

THE AMERICAN JEI.TISH COMMfTTEE

AS AMTCI CURIAE SUPPORTING APPELLEES

AND

il" rwbt w',-w h I

,4agp"t, ^1 NoT pu,.rq1^- NORMAN REDLI CH

t n^:-^^-^.< *T J.f rrustee

1 2),, HI"^ll^H.';^XpElNsoN

I t- n L - p,^1 ,b,, 4r ,*- f . ,, ;i#Hftrltfi:Tt$31f,o,

I -f\lJ.Ll l- , Lawyersr Committee for Civil

u'tr W Hff"tfi:''3:::"1?',.*.

Washington, D. C. 20005

(202) 37t-t2t2

SAMUEL RABINC'VE

The American Jewish

Committee

165 East 56 Street

New York, i{ew York 10022

Qlz) 7s1-4000

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

*Counsel of Record

JAMES ROBERTSON

HAROLD L. TYLER

Co-Chai rmen

f'

P'.

STATEMENT OT' INTEREST

The Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law is a

nonprofit organization established in 1953 at the reguest of the

president of the United States to involve leading members of the

bar throughout the country in the national effort to assure civil

rights to all Americans. Protection of the egual voting rights

of all citizens has been an important component of the Commit-

teets work, and it has suhnitted amicus curiae briefs in a nunber

of voting rights cases decided by this Court, including Escambia

Countv v. McMillant

-

U.S. , 80 L. Ed. 2d 35 (1984);

Rogers v. Lodqe, 458 U.S. 513 (1982)i McDanie1 v. Sanchez,

452 U.s. 130 (1981), and City of Mobile v. Bolden, 445 U.s. 55

(1980). The Lawyers' Committee has more than eighteen yearsr

experience in litigating voting rights cases, including several

appearances before this Court.

The American Jewish Committee is a naEional organization of

approximately 50r000 members which was founded in 1906 for the

purpose of protecting the civil and religious righEs of Jews. It

has always been the conviction of this organization that the

security and the consEitutional rights of American Jews can best

be protected by helping to preserve the security and constitu-

tional rights of all Americans, irrespective of race, religi.on,

sex or national origin.

The American Jewish Committee and the Lawyersr Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law strongly supported enactment of the Voting

Rights Act of 1965. tr{e continue to bel ieve that this landrnark

statute, as amended, must be enforced vigorously to fulfill its

objectives and therefore urge affirmance of the decision below

in the case at bar.

STATEMENT OF IPHE CASE

Amici adopt the statement of the case contained in the Brief

of Appellees.

INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF JUDGMENT

This appeal challenges a determination by a three-judge

district court that a redistricting plan enacted by the General

Assembly of North Carolina for the election of that staters

legislators had the effect of diluting black minority voting

strength in six multimember state House of Representative

and Senate districts and in one racially gerrymandered state

Senate district.

Although this appeal presents this Court with its first

plenary review of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. S

1973r since its Amendrnent by Congress in 1982, the issues

presented nonetheless fa11 within the well-developed jurispru-

dence of this Court concerning vote dilution. At stake in this

litigation is the ability of the federal judiciary under the

mandate of the Voting Rights Act to secure for black citizens the

ful1 opportunity to egually participate in the political process

and to elect the representatives of their choice.

The true significance of this case lies in the attempt by

Appellants, with the backing of the Solicitor Generalr to

debilitate the amended Voting RighEs Act by reasserting that a

careful judicial examination of the context in which a vote

dilution claim arises necessarily leads to a'proportional

representationn standard of revievr. fn additionr appellants seek

to reinfuse an intent standard into the AcE, despite its express

repudiation by Congress, by reguiring proof of racial motivation

before racially polarized voting may be weighed as an evidentiary

factor in a vote dilution claim.

It is instructive that the attempt to secure a judicial

nullification of the amended Voting Rights Act occurs in the

context of at-large elections. Beginning with Fortson v. Dorsey,

379 U.S. 433 (1955) and Burns v. Richardson, 384 U.S. 73 (1956),

and continuing through Rogers v. Lodge, 483 U.S. 513 (1982), this

Court has repeatedly viewed with skepticism the use of multimem-

ber districts in communities evidencing a history and practice of

sharp racial polarization. Although the use of at-Iarge systems

in itself violates neithef the Voting Rights Act nor the Consti-

tutionr it is long settled that these systems singularly lend

themselves to an impermissible diminution of the value of the

franchise of minority populations. In amending the Voting Rights

Act in 1982, Congress drew upon two challenges to at-large

elections to frame the proper standards for Section 2 of the

Act. See @, 412 U.S. 755 (1973) and Zimmer

v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir. 1973) (en banc) (aff'd sub

nom. East Carroll Parish School Board v. Marshal1r 424 U.S. 535

(re76).

Under the statutory "totality of the circLmstances" test

derived frorn White and Zimmerr vote dilution claims are of

necessity fact specific and must correspond to the local con-

text. North Carolina is a state with a long history of de jure

discrimination against blacks in all aspects of civil life,

including the iron-clad preclusion of any role in political

life. From the conclusion of Reconstruction until 1959, no black

had ever been elected to the State llouse of Representatives; not

until 1975 did any black ntmber among the State's Senators. The

claims of "proportional representationn can be laid to rest with

the most rudimentary examination of North Carolina political

1ife. Although blacks constitute 22.4* of the state's popula-

tionr between l-97l- and 1982 (the year this lawsuit was filed),

the number of blacks in the state llouse was between two and four

out of a total of L20i between 1975 and 1983, there were one or

two black members of the state Senate out of a total of 50. Only

five House districts and two senate districts are involved in

this litigation and, as a simple arithmetical matter, the outcome

would not and could not guarantee proportionality.

This appeal permits this Court to affirm the district

court's proper application of the congressionally specified

evidentiary factors of iIlegal vote dilution. Beyond reaffirming

the application of amended Section 2, holvever, this appeal al1ows

for a renewed declaration of the pivotal role of the federal

judiciary in securing the voting rights of Americars minority

"rarrens. If the political processes are to be utilized to

eradicate the vestiges of de jure and de facto discrimination

frorn our society, ful1 and equal participation in the political

process, including the ability to elect representatives, must be

guaranteed to minorities under careful and exacting judicial

scrutiny.

As amici, the Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

and the Arnerican Jewish Committee appeal to this Court not to

vraver from this task.

ARGUI,TENT

I. THE DISTRICT COURT PROPERLY CONCLUDED TTIAT

THE TOTALITY OF CIRCUMSTANCES DEMONSTRATED

AN IMPERMISSIBLE DILUTION OF MINORITY VOTING

STRENGTH, AND ITS ANALYSIS OF EAG OF THE

RELEVANT FACTORS WAS CONSISTENT !{ITH lHE

VOTTNG RIGHTS ACT AMENDMENTS OF 1982.

In 1982, Congress enacted a series of Amen&nents to the

Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. Sec. 1973, to secure for victims of

discriminatory vote dilution a strong and workable statutory

remedy. Particular attention was devoted to the standards of

proof for abridgment of the right to vote under Section 2 of the

amended Act as a result of this Courtrs ruling that claims of

unconstitutional vote dilution can only be premised on a showing

of discriminatory intent. City of Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55

(1980). The legistative history of the 1982 amendnents makes

unmistakably clear that the principal objective was to provide a

remedy for electoral schemes that deny minorities an egual

opportunity to participate in the political process and elect

representatives of their choice without reguiring proof of

discriminatory intent. Voting Riohts Act Extension:' Report of

the Senate Comm. of 5.1992, S. Rep. No. 4L7 | 97th Cong., 2d

Sess. at 15-15, reprinted in 1982 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News 177

[hereinafter cited as S. Rep.].1

Ith" Solicitor General argues in his brief that the Senate

Report 'cannot be taken as determinative on all counts, n and that

the statements of Senator Dole must instead nbe given particular

weight. " Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae Supporting

Appellants at 8 n.12, 24 n.49 [hereinafter cited as Br. for U.S.]

In sharp contrast is the first sentence of Senator Dolers

Additional Vierps: nThe Committee Report is an accurate statement

of the intent of S. 1992 r ds reported by the Committee. n

S. Rep. at 193 (Additional Vierps of Senator DoIe). See also

S. Rep. at 199 (supplemental views of Senaor Grassley, co-sponsor

of Dole compromise amen&nent) (oI am wholly satisfied with the

bill as reported by the Committee and f concur with the interpre-

tation of this action in the Committee Report").

ConErary to the Solicitor's contention, the Senate Report

must be regarded as an authoritative pronouncement of legislative

intent, since it was endorsed by the supporters of the original

billr Ers well as by the proponents of the compromise amen&nent.

'[R]eports of committ,ees of [the] House or Senate . may be

regarded as an exposition of the legislative intent in a case

where otherwise the meaning of a statute is obscure. " Duplex

Printinq Press Co. v. Deering, 245 U.S. 443, 474 (1920). The

government extensive reliance on the statements of witnesses

before the Senate Committee on the Judiciary is unsupportable:

nRemarks . . . made in the course of legislative debate on

hearings other than by persons responsible for the preparation or

the drafting of a bi11, are entitled to 1ittle weight

o . .n Ernst e Ernst v. Hochfelder, 425 U.S. 185, 203 n.24

(1975). See also National Woodwork Mfrs. Assoc. v. N.L.R.B., 385

U.S. 612t 539-40 (1967); N.L.R.B. v. Fruit a Vegetable Packers,

377 U.S. 58, 66 (1964)l United SEates v. Calamaro, 354 U.S. 351,

357 n.9 (1957).

The Solicitorrs position is a radical departure frorn the

previous reliance of the Justice Department on the Senate Report

as the authoritative vehicle for interpreting Section 2.

References to the Report are found throughout government argument

opposing the at-large election system in Dallas County, Alabama

(Brief for Appellant at 20,25,26,27,35r 38, 41, United States

v. Dal1as County Commission, 548 F. Supp 875 (S.D. A1a. 1982)

revrd 739 F.2d 1529 (l1th Cir. 1984), and are cited as authority

'

o revietr of the legislative history of the irg82 Amen&nen

yields three critical concerns of Congress that have direct

bearing on the present appeal:

a) Congress repudiated any nintent" standard in

section 2 cases and expressly "restore[d] the pre-Mobile tegal

standard which governed cases challenging election systems or

practices as an i1legaI dilution of the minority vote. n

S. Rep. at 27. This oresultsn test was a statutory codification

of the test used by this court in white v. Regester | 412 u. s. 75s

(1973), S. Rep. at 27, and 23 Courts of Appeals decisions, most

notably, Zimmer v. McKei !-heEr, 485 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir. 1973) (e-O

banc) affrd sub nom. East Carroll Parish SchooL Board

v. Marshal1,424 U.S.536 (1975). Under the ntotality of the

ci rcLunstancestr standa rd, plaintif f s are held to a showing that

the "political processes leading to nomination and election were

not egually open to participation by the group in question

that its members had less opportunity than did other residents in

the district to participate in the political processg to

elect legislators of their choice." White, 412 U.S. 766

b) The factors derived from these cases

the judicial inguiry into claims of vote dilution.

nthere is no reguirement that any particular number

proved r ot that a majority of them point one vray or

in more than ten pages of its twenty-five

States v. Marengo County Commission, Brief

t"q di re

eve r,

factors

o ther.

are

Eow

of

the

cE)

be

15, 19, 19, 20, 2L, 22, 23, 25, 26, 27, 36,

v. Marenoo Countv Commission, 731 F.2d 1546

page argument in United

for Appellant at

39, United SEates

(11th Cir. 1984).

7

S. Rep. at 29. Instead, "the provision requires the courtrs

overall judgnent, based on the totality of the circumstances and

guided by those relevant factors in the parEicular case, of

whether the voting strength of the minority voters is . . . rmin-

imized or canceled out. I n S. Rep. at 29 n.118, guoting Fortson

and Burns, supra.

c) Congress intended Section 2 to reach practices that

either completely negated or minimized the voting strength of

minorities. Conseguently, trthe election of a fev,r minority

candidates does not 'necessarily foreclose the possibility of

dilution of the black voter' in violation of this section. "

S. Rep. at 29 n.115, guotinq Zimmer, 485 F.2d at 1307.

Of necessity, the guestion of the existence of vote dilution

entails an intensely factual inguiry. The standard developed by

the pre-City of Mobile case l,aw and incorporated by Congress into

the 1982 Amen&nents provides the framework that highlights the

features that have recurred through the factual settings where

vote dilution has been found. These factors correspond to a

paradigmatic setting in which a claim of vote dilution

incorporates some combination of the following: (1) structural

obstacles to the electoral success of minorities, such as

multimembet#;fitt (2) a historv of discrimination and/or

absence or Jae{c-.ofminority political success, and (3) certain

behavioral patterns that accentuate the racial axis of the vote

dilution, such as racially polarized voting, racial appeals in

electoral campaigns t ot absence of responsiveness

officials.2 The juxtaposition of the particular

by elected

factual pattern

2rh" Senate Report specified the following constellation of

factors:

1. the extent of any history of official discrimina-

tion in the state of political subdivision that touched

the right of the members of the minority group to

register, to vote, or otherwise to participate in the

democratic processi

2. the extent to which voting in the elections of the

state or political subdivision is racially polarizedi

3. the extent to which the state or political subdivi-

sion has used unusually large election districts,

majority vote reguirements, anti-single shot provision,

or other voting practices or procedures that may

enhance the opportunity for discrimination against the

minority groupt

4. if there is a candidate slating process, whether

the members of the minority group have been denied

access to that processi

5. the extent to which members of the minority group

in the state or political subdivision bear the effects

of discrimination in such areas as educaLion, employ-

ment and health, which hinder their ability to partici-

pate effectively in the political processi

5. whether political campaigns have been characterized

by overt or subtle racial appeals;

7. the extent to which members of the minority group

have been elected to public office in the jurisdiction.

I\uo additional factors of lesser evidentiary significance are

mentioned:

whether there is a significant lack of responsiveness

on the part of elected officials to the particularized

needs of the members of the minority group; [and]

whether the policy underlying the state or political

subdivision's use of such voting gualification,

prereguisite to voting r ot standard, practice or

procedure is tenuous.

aigainst the paradigm model of how an electoral system can

operate to cancel out or dilute the exercise of the franchise by

racial minorities yields the conclusion whether a violation of

Section 2 of Ehe Voting Rights Act exists.

B. lHE DISTRICT COURTI S ULTIMATE

CONCTUSION OF DISCRIMINATORY

RESULTS WAS FULLY SUPPORTED BY

TIIE TOTALITY OF TT{E CIRCUM-

STANCE S

$renty years of voting rights ritigation has imparted the

clear lesson that certain electoral systems, foremost among them

multi-member districts or at-large elections, have shown them-

selves to have resulted in the i11egal dilution of minority

voting strength with such regularity that, while not Be-f Ee

violative of the Voting Rights Act, these sytems must elicit from

reviewing courts a serious prestrnption of statutory infirmity.,

rn its last ful1 treatment of a constitutional voting rights

claim, Ehis Court emphasized nthe tendenry of multi-member

districts to minimize the voting strength of racial minorities. n

Rogers v. Lodqe, 458 U.S. 513, 627 (1982). This Court has

repeatedly ruled that at-large elections violate the statutory or

constitutional rights of minority votersr3 and has directed

courts fashioning remedial decrees to avoid the implementation of

S. Rep. at 28-29 [fooEnote omitted]

3Footnote A

10

such districts.4

A wealth of social scientific literature confirms the

'conventional hypothesisn that at-large elections constitute a

significant political disadvantage for minority candidates. See

Davidson and Korbel, At-larqe Elections and Minoritv Group

Re-Presentation, 43 J. of Politics 982t 994-95 (1981) (listing

empirical studies).5 Dissenting from the application of the

constitutional intent standard in Rogers v. Lodge, Justice

Stevens focused on the inherent tendency of at-large systems to

maximize majority political power and re-emphasized this Courtrs

skeptical view of multi-member districting. 458 U.S. at 6321

4 Connor v. Johnson, 402 U.S. 690, 692 (1970) ("wh

district courts a

single-member dis

districts as a ge

u.s. 947 (1975);

re forced to fashion apportionment pla

tricts are preferable to large multi-m

en

nSr

ember

neral matter. n) ; see also YIALI-aCC_IL,_Eouse, 425

East Carroll Parish Board v. Marshall, 424

U.S. 636t 538-39 (1976) i Charrnan v. Meier, 420 U.S. 1, 18 (1975) .

5See also E. Banfield & J. Wilsonr City Politics g1-g5l

303-308 (1953); A. Karnig & S. Welch, Black Representation and

Urban PoIicy 86-99 (1980); Berry and Dye, The Discriminatorv

Effects of At-Larqe Elections, 7 Florida State University Law

Review 85, 93 (1979); Engstrom and McDonald, The Election of

Blacks to City Councils, 75 American Political Science Revievr

344-54 (f981) ; Jones, The Impact of Local Election Systems on

Black Po'l itieal Representation, 11 Urban Affairs Quar terly 3 45

, 12 Urban(1975) r Karnig, BIack Representation on Citv Councils

Affairs 0uarterly 223-242 (1975); Kramer, The Election of Blacks

to Citv Councils, L97 I Journal of Black Studies 449 (1971);

Latimer, , 15

Urban Affairs Quarterly 550 (1979) ; Robinson and Dye, Reformism

and Black Representation on Citv Councils, 59 Social Science

Quarterly 133-141 (1978); Sloan, nGood Governmentn and the

Politics of Race, L'7 Social Problems 151, L70-7 3 (1969).

In addition, studies have docranented the sharp rise in Lblack representation in southern legislatures resulting from the ! q,,

el imination of multi-member district s. &3r, e. q. , ptsrker, Raci al i "'6

cerrymanderino and Legislative ReapportiililenE-E C. oaviason, I o L

Minoritv vote Dilution 88 (1984) . I b

11

5'37-38 & n.16 (stevens, J. dissenting) (quoting 1J. Kent,

Commentaries of American Law 230-231 (12th ed. 1873) ).

The facts in this case present a clear example of the

interaction between the at-large structural impediment and the

history and behaviorar patEerns of discrimination in North

carorina.5 The district courtfs findings of fact are replete

with doctmentation of the de 'iure and de facto discrimination

against blacks in North Carolina, not only with respect to the

right to vote, but also in housing, €ducation, employment,

health, and ther public and private facilities. 590 F. Supp. at

359-64. The court noted past use of literacy tests, po11 taxes,

anti-single shot voting laws, numbered seat reguirements, and

other means to deny blacks the opportunity to register and vote,

including the continued use of a majority vote reguirement. The

court found that black voter registration rates remained de-

pressed relative to whites "because of thg long period of

official state denial and chilling of black citizensr registra-

tion efforts. r Id. at 351. Also as a consequence of the history

of discrimination, blacks continued to suffer from a lower

socioeconomic status which the court found continued bo impair

their ability to participate on an equal basis in the political

process. I-d. at 361-53. The historic use of racial appeals in

political campaigns was found to persist in North Carolina, and

5a*i"i emphasize that H*ot *.%harlenged districts

use at-large elections. The remaining district, Senate District

No. 2, was created by extensive realignment and resulted in thedivision of a black population concentration, thereby precluding

an effective voting majority. 590 F. Supp. at 358.

l2

to continue to affect the capability of blacks to elect candi-

dates of their choice. I-d. at 354. F'ina11y, voting was found to

be severely racially polarized in the challenged districts,

id. at 367-72, and black candidates to remain at a disadvantage

in terms of rerative probabitity of success in running for

office. Ld. at 367.

rn srtrn, with the singre exception of denial of access to a

candidate slating process, the district court found arr of the

factors specified in the Senate Report to exist or to have been

present in the recent past in the challenged districts. More

important, the persistent effect of each factor in isolation was

found to have a direct and appreciable impact on present minority

political participation which continued t,o disadvantage blacks

relative to whites. In fignt of these findings of facts, the

district court concluded that the sign posts for vote dilution

drawn from the case law and legislative history all pointed to

the dilution of minority voting strength in the multi-member

districts and the single-member Senate district.

II. APPELLANTS SEEK TO NULLIFY THE 1982 AMENDMENT

TO TEE VOTING RIGHTS ACT BY FORECr,OSING TIIE

JUDICIAL INQUIRY INTO THE TOTALITY OF lrHE CIR-

CUMSTANCES WHICE GIVE RISE TO CT,AIMS OF VOTE

DILUTION.

Congress drew upon White and Zimmer as a model judicial

interventions to remove structural barriers to minority access to

the political process. It bears emphasis that many of the

factors focused upon in white and its progeny are not in them-

13

selves either illega1 or unconstitutional but may nonetheless, in

their aggregate, trigger the need for remedial intervention.

"[T]he facts in White set the contours for the puzzle, but the

blank spaces could be filled in with different pieces. . .n7

Appellantsr argunents before this Court would defeat the

overall inguiry into the structures, pf,actices and behaviors

affecting minority poritical opportunity in two critical l/ays:

first, appellanEs seek to reintroduce an intent standard into the

well-developed concept of racially polarized voting, and second,

appellants would have the multi-factored White -immer analysis

negated by the episodic election of black candidates.

A. THE USE OF STATISTICAL ANALYSIS AND

LAY W]TIIESSES TO ESTABLISH RACIALLY

potARIZED VOTING WrlgOUT ANy INQUIRY

rNTO VOTER MOTIVATION IS FULTY SUP.

PORTED BY THE CASE LAW AND I]HE

LEGISLATIVE IIISTORY OT SECTION 2.

1. The Facts Support A Finding of

Racially Polarized Voting.

Racially polarized voting is a key component of a vote

dilution claim. nrn the context of such racial bloc voting, and

other factors, a particular election method can deny minority

voters eguar opportunity to participate meaningfully in erec-

tions.n S. Rep. at 33. As this Court wrote in Rogers,

Voting along racial lines alIows those elected to

ignore black interests without fear of political

conseguenc€sr and without bloc voting the minority

candidates would not lose elections sole1y because of

THartman, Racial Vote Dilution and Separation of Powers: An

Exploration of the Conflict Between the Judicial "fntentn and the

Legislative nResultsn Standards, 50 Geo. Wash. L. Rev. 689, 699

(1e82).

14

their race.

458 U.S. at 623. Racially polarized voting, when proven,

provides a court with a critical evidentiary piece showing the

political ostracism of a racial minority. City of Rome v. United

States, 471 F'. supp. 22lt 226 (D.D.C. L97g), af f rd 446 U.S. 156

(I980). When combined with either at-large elections or a

suspected gerrymander, bloc voting provides important confirma-

tion that the potential structural impediments to minority

political opportunity will in fact bar equal opportunity and the

ability to egually elect the representatives preferred by the

minority community. ggg United States v. Marengo County Commtn,

731 F.2d 1545, 1556-67 (11th Cir. 1984) (raciaIly polarized

voting ordinarily the "keystone" of a dilution claim) ; Nevett

v. Sides, 571 F.2d 2Ogt 223 n.15 (5th Cir. 1978), cert. deni!d,

445 U.S. 951 (1980).

In the present case, based on evidence presented by expert

witnesses and corroborated by the direct testimony of 1ay

witnesses, the district court concluded that "within all the

challenged districts racially polarized voting exists in a

persistent and severe degree.' 590 F. Supp. at 36-7. The

district court relied in part on testimony by plaintiffsf expert

witness, Dr. Bernard Grofman, whose comprehensive study of racial

voting patterns in 53 elections in the challenged districts

revealed consistently high correlations between the nunber of

voters of a specif:.c race and the number of votes for candidates

of that race. These correlations were so high in each of the

15

elections studied that the probability of occurrence by chance

was less than one in 1001000. 590 F. Supp. at 368.

The uncontraverted evidence showed that gg black candidate

received a majority of white votes cast in any of the 53 elec-

tions, including those which lrere essentially uncontesEed. Id.

Whites consistently ranked black candidates at the bottom of the

field of candidatesr €v€D where those candidates ranked at the

top of black votersr preferences. Id. The district court

individually analyzed elections in each of the challenged

districts to conclude that, in each district, racial polarization

"operates to minimize the voting strength of black voters. n

of nurnerous Iay witnesses involved in North Carolina electoral

politics. Given the overwhelming and uncontradicted facts of

this case, there is no guestion but, that racial polarization in

each district wESr as Ehe district court properly found, 'sub-

stantial or severe.' 590 F. Supp. at 372.

2. The District Court Applied Every

Accepted Methodology for Proving

Racially Polarized Voting.

Proof of racially polarized voting has been provided in the

case law by three types of evidence: a) bivariate or ecological

regression analysis performed by an expert; b) extreme case or

homogeneous precinct analysis performed by an expert; c) lay

testimony. The district courtrs findings of racially polarized

voting rested on evidence drawn from each of these methods of

analysis,590 F. Supp. at 367-68 n.29, and conforms to every

I5

regui rement derived f rcrn prior voting rights cases.

a. Bivariate regression graphically compares the votes

for minority candidates in each precinct with the racial composi-

tion of that precinct, examining the corretation between the

nunber of voters of one race and the nurnber of votes received by

candidates of the same race. This technique examines both

racially segregated and racially mixed precincts, providing

correctives to reflect the differences in voting behavior among

precinct s.

Polarized votingr ds the district court observed, is

considered statisticallv significant if the relationship between

the variables indicated by correlation coefficients is suffi-

cientry consistent, and substantively significant if it is of a

suf f icient magnitude to affect the outco,me of an election. 590

F. Supp. at 367-369. See McMillan v. Escambia Countv, 538

F.2d 1239t l-24l- n.6 (5th cir. 1981), afffd on rehearinq, 688 F.2d

960r 966 n.12 (5th Cir. 1982) rev'd on other qrounds, Escambia

County v. McMillant _ U.S. , 80 L. Ed. 2d 35 (1984)

(hereinafter Escambia f); Mcl1i1lan v. Escambia Countyr T43 F.2d

1037, 1043 n.12 (5th Cir. 1984) (affirming the definition of bloc

voting and related findings made in Escambia I). Because of its

precision in isolating the racial breakdown of election results,

bivariate regression is the preferred method of proving racial

bloc voting. S

The surest method of demonstrating racial bloc voting

t7

b. Homogeneous precinct analysis, also known as 'extreme

casen analysis, statistically compares the voting patterns in

precincts with heavy concentrations of one race (90t of the

population or more) and other precincts with comparable concen-

trations of another race. This technigue ascertains the

existence of polarized voting by measuring a nracial polarization

index, n which is determined by subtracting the votes cast for a

minority candidate in homogeneous white precincts from the

percentage of votes cast for the same candidate in honogeneous

minority precincts. SCC City of Port Arthur v. United States,

517 E'. Supp. 987, 1007 n.136 (D.D.C. 1gg1), aff 'd 459 U.S. 159

(1982) . While nurnerous courts have accepted this analysis in

making findings of polarized voting, they have differed slightly

is to analyze the results, broken down into a nwnber of

districts of differing racial makeup, of an election in

which a white candidate is pitted against a black one.

If there is a positive correlation in a sufficient

number of districts between voters of one race and the

percentage of votes received by the candidate of that

race, then it can be inferred that racial bloc voting

has occurred.

United SEates v. Marenoo County Commission, 73I F.2d 1546, L567

n.35 (1lth Cir. 1984);

739 F.2d 1529, 1535 n.4 (1lth Cir. 1984);

Lubbockr T2T F.2d 364,380 (5th Cir. 1984); NAACP bv Campbel

v. Gadsden Countv School Board, 69L F.2d 978, 983 (I1th

Cir. 1982); Jordan v. Wi nter, 604 F. Supp. 807, 812-813(tt.O. Miss. 1984); aff 'd sub. nom.

Executive Committee v. Brooks , _ U. S. , 83 L. Ed. 2

(1984); Major v. Treen, 574 F. Supp. 325t 337 (8.D. La. 19

Taylor v. Havwood County, 554 F. Supp. 1122, 1-126

(W.D. Tenn. 1982) i Parnell v. Rapides Parish School Board,

F. Supp. 399, 405 (w.o. La. 1975), aff'd 563 F.2d 180 (5th

d. 343

83) ;

42s

Cir. 1978); Bolden v. City of Mobile, 423 F. Supp. 384, 388-89

(S.O. AIa. L976), aff'd 571 F.2d 238 (1978), rev'd on other

groundst 445 U.S. 55 (1980).

18

on the specific index score needed to constitute proof.g

c. In additionr courts have relied on non-statistical

evidence to supplement the testimony of experts to make up for

the unavailabitity of expert testimony:

A per se rule requiring that Plaintiffs show actual

black-white city election breakdowns in order to

demonstrabe polarized voting would enable offiials to

negate an important elernent of a voting rights action

simply by forcing all voters to come to one polling

p1ace. The Court, finds that when direct evidence as

to racial voting patterns is unavailable, the Court

must look to indirect evidence.

Terrel lr E-ggEB, 555 F. supp. at 348.10

C. APPELLANTS AND THE SOLICITOR GENERAL

SEEK TO REIMPOSE AN INTENT STANDARD

ONTO SECTION 2 CLAIMS BY RMUIRING

PROOF OT MOTIVATION OF VOTERS.

Despite the district courtrs reliance on all three forms of

evidence of racial bloc voting, appellants groundlessly accuse

the court of adopting as a measure of racial bloc voting the

standard of less than 50? of white voters casting a ba11ot for

the black candidate. Appellantsr Brief at 35. The court

gEgSr er-gr, Political Civil Voters Organization v. Citv of

Terrel1,565 F. Supp. 338, 348 (n.o. Tex. 1983) (a score of 50 or

70 proves polarized voting); Port Arthur, suprar 51-T F. Supp. at

1007 n.13e (polarization significant when scores are in excess of

50 or 50). See also Perkins v. City of Diest He1ena,675 F.2d

20!t 213 (8th Cir. 1982); Lipscomb v. hlise, 399 F. Supp. 7821

785-786 (ll.n. Tex. 1975), revrd on other qrounds, 551 F.2d 1043

(5th Cir. 1977), revrd 437 U.S. 535 (1978).

lOsee also Major v. Treenr SlIpF-3r 57 4 F. Supp. at 338

(testimony of trained political observers considered probative of

bloc voting); Rome, supra, 472 F. Supp. at 226-227 (finding

testimony of black deponents highly probative of bloc voting);

Boykins v. City of Hattiesburq, No. H7 7-0052(C) , slip op. at 15

(S.p. Miss. Mar. 2r 1984) nlay witnesses from the White community

. . . confirmed that members of the White community continue to

oppose and fear the election of Blacks to office. n)

19

indicated that the purpose of both methods of statistical

evaluation relied upon by the plaintiffs' expert witness was

simply "to determine the extent to which blacks and whites vote

differently from each other in relation to the race of candi-

dates. n 590 F. Supp. at 367 n.29. Only after concluding thaE

substantively significant racial polarLzation existed in alI but

two of the elections analyzed did the district court note that no

black candidate had received a majority of the white votes cast.

The court specifically referred to this finding as one of a

nunber of n Ialdditional factsn which nsupport the ultimate

finding that severe (substantively significant) racial polariza-

tion existed in the multi-member district elections considered as

a who1e." Id. at 358 (emphasis supplied1.11

The principal method for measurement of racial polarization

relied on by the court below was statisticallv siqnificant

correlation between the number of voters of a specific race and

the nunber of votes for candidates of that race. 590 F. Supp. at

367, 358. The Solicitor Generalrs charge tht, under the lower

courtrs methodology, a ominor degree of racial bloc voting would

be sufficient to make out a violationr" Br. for U.S. at 29, is

gravely misleading since it focuses on the lower courtrs defini-

tion of substantive significance without acknowledging the

1}rh" Solicitor General has also conceded in his brief in

support of the Jurisdictional Statement that nIa]ppellantsl

restatement of the district courtrs standard for racial bloc

voting is imprecis€, n since "the district court did not state

that polarization exists unless white voters support black

candidates in numbers at or exceeding 50t.n Brief for the United

States as Amicus Curiae at 13 n.10.

20

courtrs initial definition of racial polarization as also

reguiring statistical significance. To the contrary, to the

Solicitor's conclusion that a "minor degree of racial bloc

voting would be sufficient to make out a violationr' Br. for

U.S. at 29, a low correlation would result in a finding of a Iow

extent of polarization and would weigh against an ultimate

conclusion of impermissible vote dilution.12

Both the Solicitor GeneraL and appellants propose methods to

discount the importance of racial bloc voting by reguiring proof

that racial motivation underlies the disparate voting patterns.

Appellants would hold plaintiffs to a nightmarish standard of

conclusively establishing the intent of the electorate by

disproving possible motivation by nany other factor [besides

racel that could have influenced the election. n Br. for appel-

lants at 42. The Solicitor General similarly advocates a

standard reguiring only that n'minority candidates not }ose

elections solely because of Eheir race.'n Br. for U.S. at 31

(guoting Rogers v. Lodqe). This standard, iE is argued, would

12tho", the hypothetical situation in which a white candidate

receives 51t of the white vote and 49t of the black vote and an

opposing black candidate gets the reverse would clearly not

constitute severe polarizaEion, as the government contends. See

Br. for U.S. at 29. In fact, since such a disparity would not be

statistically significant, it would not constitute racial

polarization at all. The suggestion that the district courtrs

definition of racial polarization would invalidate numerous

electoral schemes across the countryr Sge i-d. at 30, conveniently

ignores the fact that the courtrs correlation analysis correctly

focused on "the extent to which voting . is racially polar-

ized." s. Rep. at 29 (emphasis supplied). Racial po}arization

is properly evaluated as a guestion of degree, and not as a

dichotomous characteristic which is Iegally conclusive if present

and irrelevant in all other cases.

2t

render racial bloc voting nlargely irrelevant, tr i-d.; if a losing

black candidate receives some unspecified amount of white

support, this would demonstrate that motivational factors other

than race play a role in the election.

Congress has made it plain that Section 2 plaintiffs are no

longer reguired to ascribe nefarious motives to the individuals

or community responsible for discriminatory election results;

thusr it is immaterial whether white voters refuse to vote for

brack candidates nsolery because of racen or because of sorne

other factor closely associated with race. The impact of racial

bloc voting on minority politicar participation is the same

regardless of the explanaEion or motivation for that phenomenon.

rn the presence of other white,/zimmer factors, if white voters

consistently shun black candidates for reasons other than race,

the result is stil1 that the black community is effectively shut

out of the politicar proce"".13 tn delineating the factors

relevant to a showing of unequal opportunity to participate in

the political process, Congress relied heavily on federal circuit

13rhi. point is also responsive to appellants' objections tothe statistical methodology relied upon by the district court,

which was characterized by appellantst own expert witness as a

standard methodology for measuring racial voting polarization.

Tr. at 1445. It simply does not matter whether orace is the only

explanation for the correspondence between variables. n AppeI-

lants' Brief at 42. Where differential voting along racial linesexistsr for whatever combination of reasons, the result in the

context of structural impediments such as at-large or multi-mem-

ber district elections can be a dilution of the minority vote

which renders minorities unable to elect representatives of theirchoice. This resurt is a violation of the voting Rights Act

regardless of the existence or nonexistence of proof of racial

animus on the part of whites who fail to vote for blacks.

22

court interpretations of r{hite, none of which adopted a defini-

tion of racial polarization that supports the standard urged here

in fact, most of them required no formal proof of polarization

whatsoever.l4 Moreover, last Term, this Court rejected the

argument that racial motivation of voters casting ballots for

candidates of their own race must be established to prove

racially polarized voting. Mississippi Republican Executive

M, t . s. ,

-

L. Ed.2d

-.15

III. THE DISTRICT COURT DID NOT ERR IN CONCT,UDING

1TIAT TTIE ELECTION OF SOME MINORITY CANDIDATES

DID NOT ALTER TEE HTSTORIC PATTERN OF LACK OF

OPPORTUNITY OF BLACK CANDIDATES, NOR DID IT

ADOPT A PROPORTIONAL REPRESENTATION STAI{DARD.

A. The Election of Some B1ack Officials

Did Not Disprove tack of Egual

Opportunity to EIect Minority Officials.

Appellants contend that "the degree of success at

enjoyed by black North Caroliniansn distinguishes this

the polIs

case from

la$gg e.cr., Ferouson v. winn Parish PoIicy Jurvr 528 F.2d

592 (5th Cir. L975)i Robinson v. Commissioners Court, 505 P.2d

674 (5th Cir. 1974)i Moore v. Leflore Countv Board of Election

Commissioners, 502 F.2d 621 (5th Cir. L974) i

490 F.2d 191 (5ttr Cir. 1973). The original Zimmer factors

themselves did not even include racially polarized voting. See

Zimmer | 485 at 1305

lspefendants, represented by the same counsel as at present,

argued that, nlhe use of a regression analysis which correlaEes

only racial make-up of the precinct with race of the candidate

ignores the reality that race . . . may mask a host of other

explanatory variables. [Jones v. City of Lubbock, 730 P.2d 233,

235 (5th Cir. 1984) (Higginbotham concurring).ln Jurisdictional

Statement at 12-13. This Court summarily affirmed the district

courtts decision in that case and, therefore, 'rejectIed] the

specific challenges presented in the statement of jurisdictionr"

Mandel v. Bradlev, 432 U.S. l73t L76 (L977).

23

prior vote dilution cases. Br. of Appellants at 24. Similarly,

the Solicitor General asserts that the challenged multimember

districts have napparently enhanced not diluted -- minority

voting strength." Br. for u.s. as Arnicus curiae at 24. Both

Appellants and the Solicitor General cite the extent of claimed

minority success as a principal reason for overturning the

district court. This argument is wrong as a matter of law and

fact.

To begin with, Congress spoke without eguivocation that the

degree of minority electoral success is none factor which B-ey be

considered . . .' 42 U.S.C. 1973 (emphasis added). See also

S. Rep. at 29 (nthere is no reguirement that any particular

nunber of factors be provedr or that a majority of them point one

$ray of the other.'). Indeed the proviso in Section 215 oru"

enacted in response to concern that a results test would devolve

into a standard focuses so1ely on the extent of minority elec-

toral success. The Senate Report expressly disavows the proposi-

tion that the success of a few black candidates will foreclose

the possibility of a finding of racial vote dilution. S. Rep. at

29 n.115 (guoting zimmer v. McKeithent 485 E.2d at 1307). fn

Zimmer, the court concluded that, despite the fact that two of

the three candidates elected to the school board in 1972 were

16nP.orrided, that nothing in this section establishes a

right to have members of a protected class elected in numbers

egual to their proportion in the population." 42 U.S.C.

Sec.1973.

24

black, plaintiffs had proven vote di1ution.17 The conclusion of

the Zimmer court that electoral successes do not preclude a

finding of vote dilution is echoed in nunerous decisions both

prior to this Court's ruling in Citv of t'tobileI8 and in post-19g2

amendrnent cases.l9

In rushing to herald the electoral success of North Carolina

blacksr appellants and the Solicitor General overlook the

critical findings of fact of the district cour 1.20 The statewide

17n[!ri]e cannot endorse the view that the success of black

candidates at the poIls necessarily forecloses the possibility of

diluticn of the black vote. Such success mightr oD occasion, be

attributable to the work of politicians, who, apprehending that

the support of a black candidate would be politically expedient,

campaign to insure his election. Or such success might be

attributable to political support motivated by different consid-

erations namely that election of a black candidate will thwart

successful challenges to electoral schemes on dilution grounds.

In eiEher situation, a candidate could be elected despite the

relative political backwardness of black residents in the

'electoral district. Were we to hold that a minority candidate's

success at the pol1s is conclusive proof of a minority group's

access to the political process, we would merely be inviting

attempts to circunvent the Constitution. This we choose not to

do. fnsteadr w€ shall continue to reguire an independent

consideration of the record.o 485 F.2d at 1307.

lSMcfntosh County Branch of NAACP v. Citv of Darien, 605

F.2d 753, 756 (5th Cir. 1979); Cross v. Baxter, 604 F.2d 875t 885(5th Cir. 1979)i United States v. Board of Suoervisors of ForresE

Countv, 57L F.2d 951, 955 (5th Cir. 1978); Kirksey v. Board of

Supervisors of Hinds Countyt 554 F.2d 139, 149 n.ZL (5th

Cir. L977) | cert. den. 434 U.S. 877 (1977)i Graves v. Barnes

(Graves II),378 F. Supp. 640, 648,559 (w.D. Tex. L974) vac'd on

other qrounds, 422 U.S. 935 (1975); Wallace v. Houset 377

F. Supp. 1192, 1197 (W.O. La. L974) , aff 'd in part and rev'd inpart on other qrounds, 515 F.2d 519 (5th Cir. 1975); Beer

v. United SLates, 374 F. Supp. 363, 398 and n.295 (D.D.C. 19741,

vacrd on other qrounds, 425 U.S. 130 (1975); Yelverton v. Driq-qers, 370 F. Supp. 6L2, 515 (S.o. AIa. 1974).

I 9Footnote.

20rinding= subject to Rule 52(a) ctearly erroneous standard.

25

figures reveal that there vrere never more than four blacks

North Carolinars 120-member House of Representatives betwee

and 1982, and never more than two blacks in the 5O-member State

Senate from 1975 to 1983. 590 F. supp.345 at 355. fn the

period from 1970 to L982, black Democrats in general elections

within the challenged districts lost at three times the rate of

white Democrats. Tr. 114.

The district courtrs findings with respect to the L982

elections showed that there were 'enough obviously aberrational

aspects in the most recent electi.onsr' 590 F. Supp. at 367, to

reject the contention that blacks were not still disadvantaged in

the multi-member districts at issue. Although black candidates

did enjoy some degree of success, it did not nearly rival the

),rt,,.ol

success of white candidates, not a single one of whom lost in the

general elections{ tr. 114, I1n n House District 35, a black

Democrat won one of E s in the district in 1982. Since

there were only seven white candidates for the I seats in the II

prirnaryr, it w4s a mathematical certainty Ehat a !lack would win.

I t.t ...1' ,': ! /LL){, ' ,+t, ,,!. \ ''' ..r : t tti".; li-. , t.

I3. at 359.

^

ID House District 23, there were only 2 white/\

candidates for 3 seatg .t" the 1982 primary, and the black

candidate who *on

'run,.unopposed

in the general election, but

i\ i,

still received only 43* of the whit vote. Ig. at 370. In three.

other elections prior to 1982, the same black candidte won in

unopposed races, yet failed to receive a majority of white

votes in each contest. I-d.

The district court made two critical findings of fact

t\.L_.r&

\7

26

'concerning

the purported electoral successes of blacks in Nort

Carolina. First, even in elections where black candidates brer

vicEorious, witnesses for the plaintiffs and defendants alike

agreed that the victories were largeLy due to extensive

single-shot voting by b1acks.21 Tr. 85, 181, l-82, 184, 1099.

Even Ehe defendantsr expert witness conceded that, nas a general

rule, n black voters had to single-shot vote in the multi-member

districts at issue in order to elect black candidates.

Tr. L437. Thus the district court determined, " [o]ne revealed

conseguence of this disadvantage is that to have a chance of

success in electing candidates of their choice in these dis-

tricts, black voters must rely extensively on single-shot voting,

thereby forfeiting by practical necessity their right to vote for

a fuII slate of candidates.n 590 F. Supp. at 369.

The district court also concllded that the evidence at trial

,

showed that in several of the 1982 elections, nthe pendency of

thisvery1itigationworkedasaone-timeadvantageforb1ack

candidates in the form of unusual political support by white .*

Ieaders concerned to forestall single-member districting. n 590

F. Supp. at 367 n.27. This is exactly the concern which led the

2lsingIe-shot voting occurs when minority voters concentrate

their voting strength on one or a few preferred candidates and

deliberately fail to exercise their right to cast ballots for

other candidates in the race. The purpose of single-shot voting

is to enhance the likelihood of a minority candidaters election

by depriving nonminority candidates of the minority vote;

however, it also has the effect of completely eliminating any

influence minority voters might have over the choice of the

elected nonminority candidates. See Citv of Rome v. U. S. , 446

U. S. I56, 184 n.19 (1980) .

1

27

Zimmer court to reject assertions identical to those advanced by

the appellants here.

In srtrn, the evidence amply supported the district courtrs

conclusion that:

[T]he success that has been achieved by black candi-

dates to date is, standing alone, too minimal in total

nunbers and too recent in relation to the long history

of complete denial of any elective opportunities to

compel or even arguably to support an ultimate finding

that a black candidate's race is no longer a signifi-

cant adverse factor in the pol itical processes of the

state -- either generally or specifically in the areas

of the challenged districts.

590 F. Supp. at 367.

B. Appellants Claim that the District Court

Imposed a Proportional Representation

Standard Harken Back to the Defeated

Arguments of Opponents to the 1982 Amend-

ment to the Voting Rights Act.

Without doubt the most inflammatory claim that can be raised

in a vote dilution case is the charge of proportional representa-

tion. Cf. Iln i t'ed .Tcr.r i sh Orqanizations v. Carev, 430 U.S. l44l

155-167 (1977). Appellants seek to obscure the district courtrs

careful examination of all the White,/Zimmer f actors by raising

the blazing charge that the district court "flat1yn stated a

standard of "guaranteed proportional representation.n Br. for

Appellants at 19. In appellantsI eyesr dny reference to the

actual proportions of blacks in North Carolina as compared to

black electoral success reveals the entire factual inguiry to

have been a subterfuge designed to conceal an imposition of

proportional representation.

Consideration of minority electoral success is one of many

28

evidentiary factors which the case law and legislative history of

the Voting Rights Act specify as proper grounds for judicial

examination. The Leap between the evidentiary weighing of the

rate of success and an ipso facto creation of an entitlement to

proportional representation is derived from the pivotal arguments

made by opponents of the t982 Amen&nents to the voting Rights

Actr namely that there is no intelligible distinction between a

results test and proportional representation.22 thi" claim was

the most disputed issue which faced Congress in its deliberations

on the legislation, and it was the concern which most evidently

divided the billrs supporters and detractors. The proportional

representation argument was firmly rejected both by the sponsors

of the original amen&nent and the proponents of the Dole compro-

mise. SeeT €.e.7 S. Rep. at 33 (n[T]he Section creates no right

to proportional representation for any group") ; i-d. at 194

(Additional Views of Senator DoIe) ("I am confident that the

rresultsf test will not be construed to reguire proportional

representationn). Since the district court properly considered

the totality of circumstances under the mandated legal standardsr

22sec e.9. , I

Comm. on the Judiciary, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. 3 (1982) [herein-after cited as Senate HearinqsJ (Opening Statement of Senator

Orrin Hatch) ('ln short, what the rresults' test would do is to

establish the concept of rproportional representationt by race as

the standard by which courts evaluate electoral and voting

decisionso). A ful1 discussion of the proportional representa-

tion objections of the legislationrs opponents can be found in

the Senate Subcommittee's Report. See S. Rep. at 139-147 (Voting

Rights Act: Report of the Subcomm. on the Constitution) ; see

also jd. at 185-87 (Attachment B of Subcommittee Report:

Selected Quotes on Section 2 and Proportional P.epresentation).

29

Ehe effort to persuade this Court that it in fact reguired

proportional representation can only be understood a an inviEa-

bion to embrace the views of opponents to the 1982 amendments and

should categorically be declined.

IV. CTAIMS OF VOTE DILUTION, LIKE ALL CLAIMS

OF AN ABRIDGMENT OF lEE FRANGISE, ARE

ENTITLED TO SPECIAL JI'DICIAL SOLICITUDE

BECAUSE OF IIIE FUNDAMENTAL NATURE OF THE

RIGHT AT STAKE.

Based upon an exhaustive reviery of the background, struc-

tures and behaviors involved in the North Carolina legislative

elections, the district court unanimously concluded, under the

statutory results test, that the legislative redistricting

abridged the voting rights of blacks. Of particular signifi-

cancer the court revealed the continued taint of discriminaEion

upon all walks of North Carolina's civil life. As the Voting

Rights Act and other pieces of civil rights legislation make

c1ear, the political processes may provide critical relief for

the victims of past and continuing discrimination providing

that those channels are open to victimized minorities.

The Voting Rights Act sets out to remove structural barriers

to minority access to political processes in order to facilitate

the amelioration of the vestiges of discrimination. The Act

corresponds to a heightened standard of judicial scrutiny set

down by this Court nearly half a century ago:

IP] rejudice against discrete and insular minorities may

be a special condition . curtailing the operation

of those political processes ordinarily to be relied

upon to protect minorities, and lso1 may call for a

30

correspondingly more searching judicial inguiry.

United States v. Carolene Products Co., 304 U.S. 144, 152 n.4

(1938). Foremost among the rights specified by what Justice

Powell has termed nthe most celebrated footnote in constitutional

Lawr"23 is the right to vote. Id., citinq Nixon v. Herndon, 273

U.S. 535 (I8 ) and Nixon v. Condonr 2S6 U.S. 73 (18 ). This

Court has repeatedly stressed the need for judicial vigilance in

claims of vote dilution or abidgrnent as set forth in the Carolene

Products footnote:

Undoubtedly, the right of suffrage is a fundamental

matter in a free and democratic society. Especially

since the right to exercise the franchise in a free and

unimpaired manner is preservative of other basis civil

and political rights, any alleged infringment of the

right to vote must be carefully considered and meticu-

lously scrutinized.

Revnolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 561-562 (1954) ; see also B-arceI

v. Virqinia ,St-ate Bd. of Elections, 383 U.S. 553 (195 ); Yick

Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1885).

So long as the paths to political success remain closed,

blacks remain the "discrete and insular'minorities of the

Carolene Products footnote to whom a special measure of judicial

solicitude is owed. See Ackerman, Bevond Carolene Productsr 98

IIarv. L. Rev. 713, 733-37 (1985) (need for political success for

minorities to transcend npariahn role in political process).

23Powe11, J.,

Co1. L. Rev. 1087

Carolene Products Revisited, 82

(1982).

31

Conversely, nrepresentation-reinforcing'24 judicial intervention

is the most efficacious manner by which this Court may insure

that the goals of two decades of statutory civil rights Iitiga-

tion may one day be met. tsection to follow relating this

argument to legislative history of Section 2-l

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, amici urge that the judgment of

the district court be affirmed.

24J. EIy, Democracy and Distrust, 101-103, Ll.'l (1980). See

also i-d . at 10 3 :

Malfunction occurs when the process is undeserving of

trust, when (1) the ins are choking off the channels

of political change to ensure that they will stay in

and-the outs will stay out, or (21 though no one is

actually denied a voice or a voter representatives

beholden to an effective majority are systernatically

disadvantaging some minority out of simpl9 hgstility or

a prejudiced iefusal to recognize commonalities of

inLerest, and thereby denying that minority the

protection afforded otfrer groups by a representative

system.

32

Respectf u1 ly submitted,

JAMES ROBERTSON

EAROLD L. TYLER

Co-Chai rmen

NORMAN REDLICH

Trustee

WILLIAM L. ROBINSON

FRANK R. PARKER*

SAMUEL ISSAGIAROFF

PATRICIA M. HANRAHAN

Lawyersr Committee for Civil

Rights Under taw

1400 'Eye' Street, N.W.

Suite 400

Washington, D. C. 20005

1202) 37t-t2t2

SAMUEL RABINCI/E

RICEARD FOLTIN

The American Jewish Committee

155 East 55 Street

New York, New York 10022

(2t2) 751-4000

Attorneys for Amici Curiae*

*Counsel of Record

*The attorneys for amici gratefully acknowledge the assist-

ance of Martin Buchanan and Roger Moore, students at Harvard Law

Schoolr on the brief.

33