Brief in Support of Defendants' Motion to Quash Subpoenae; Plaintiffs' Response to Defendants' Motion to Quash Subpoenae

Public Court Documents

December 14, 1981

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Williams. Brief in Support of Defendants' Motion to Quash Subpoenae; Plaintiffs' Response to Defendants' Motion to Quash Subpoenae, 1981. 7bc1e27b-d992-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b43be161-637d-4233-8c16-5f061e57abdb/brief-in-support-of-defendants-motion-to-quash-subpoenae-plaintiffs-response-to-defendants-motion-to-quash-subpoenae. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

i'

I

D

I

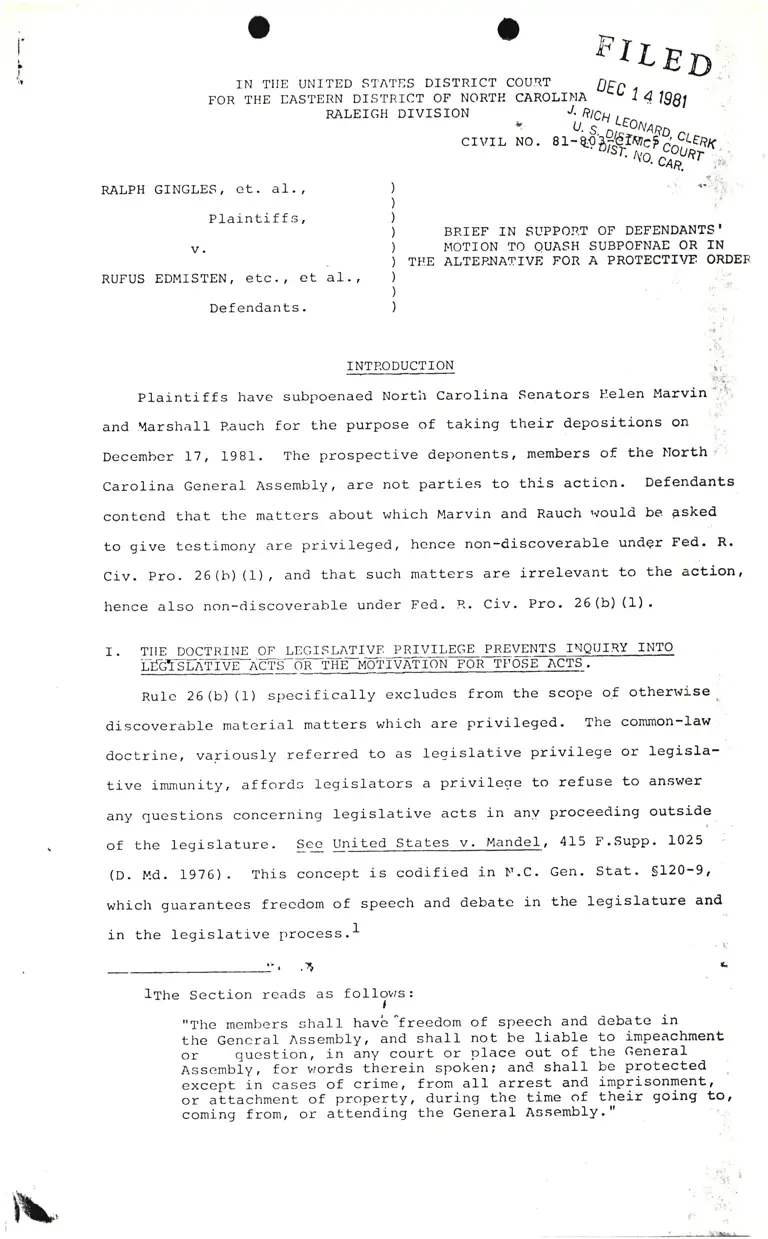

\l IN TIIE UNITED STAT}1S DISTRICT COU]17

THE DASTERN DISTRICT OF NORT}I CAROLII'IA

IT-TT ED

oEc I 4 BBt

No . s r- Qg 36?:fg.F,,??l

1,$;a;usri,.*Yatax+i#{.,2,g

FOR

RALEIGH DIVISION

RALPH GINGLES, Qt. aI.,

Plainti ffs,

v.

RUFUS EDMISTEN, etc. , et af. ,

CI\ITL

t'.,

BRIEF' IN SUPPOP.T OF DEFENDANTS I

I{OTION TO QUASH SUBPOFNAE OR IN

THE ALTEPNATIVE FOR A PROTECTIYE ORDEF

Defendants.

INTP.ODUCTION

plaintiffs have subpoenaed Nortir Carolina Senators Uelen Marvin l'i'

and Marshall pauch for the purpose of taking their depositions on

December ;-7, 1981. The prospective deponents, members of- the llorth '

Carolina General Assembly, are not parties to thls action. Defendants

contend that the matters about which l4arvin and Rauch rvould be Ssked

to give testimony are privileged, hence non-discoverable under Fed. R.

Civ. pro. 26 (b) (1) , and that such matters are irrelevant to the action,

hence also non-cliscoverable under Fed. F.. civ. Pro. 26 (b) (1).

I. TIIE DoC,i.IlINE OF LtrGISLATIVE PRIVTLEGE PREVENTS IIIQI]]RY INTO

r,-E-cTsr,rrrrvn neT5-on r-ua-llorffETroN r'6n trosE Acrs .

RuIe 26(b) (1) specifically excludes from the scope of otherlise,

discoverable material matters which are privileged. The common-law

doctrine, variously referred to as legislative privilege or legisla-

tive immunity, affords legislators a privilege to refuse to answer

any questions concerning legislative acts in anv proceeding outside

of the legislature. q"i , 415 F.Supp. L025

(o. Md. 1976). This concept is codified in N.C. Gen. Stat. 5120-9,

whicl'r guarantees frecdom of speech and debate in the legislature and

in the legislative p.o".=".1

,.7

lrhe Section reads as follovrs:

,'The members shall havb ^freedom of speech and debate in

the General Assembly, and shall not he liabIe to impeachment

or guestion, in lny court or place out of the General

Assembiy, for vrords therein spoken; and shall be protected

except in cases of crime, from all arrest and imprisonment,

or attachment of property, during the time of their going to,

coming from, or attending the General Assembly. "

'L

-2.-

North Carolina's statutory provision pararllels the Speech or

Debate Clause of the Federal Constitution (art. I, 56), as well.

as the statutory and constitutional enactments of most other

states. In interpreting the federal constj-tutional version of,,,

this doctrine the United Statesupreme Court has written:

,.-i

;"

r ,; ...fr4.

{t:'

.C..'

';: l:{..

'','l't'

'.

rtL'

:1.

The reason for the privilege is clear. It r.ras

weIl summarized by James Wilson an influential

member of the Committee of Detail which rras

responsible for the provision in the Pederal

Constitution. "In order to enable and encourage

a rcpresentative of the public to discharge his

public trust r'rith firmness and success, it i.s

indispcnsably necessary, that he should enjoy

the fullest liberty of speech, and tt'.at he

should be protected from the resentment of every

one, however porverful, to r'rhom the exercise of that

liberty may occasion offence." Tenney v. P,roadhove,

341 u.s. 367 (1951) at 372-73 (cltTEions omTffi).-

Legisl-ativo privilege has a substantj.ve as weLl as evidentj..ry , ,

aspect, and both are founded in the ratj-onaIe of legislative

integrity and independence, enunciated by the Framers and propounded

two centuries later by the SupreriTe Court. The substantive aspec,t ,1..

of the doctrine affords legislators immunity from civil anrl criminal

liability arising from legislative proceedinqs. The evidentiary

aspect. affords legisLators a privilege to refuse to test,ify about

legislative acts in proceedings outside the legislativo halls. United

State v. llandel, guprg at 1027.

At issue here is the evidentiary facet of the privileqe and,

specificalIy, rvhether such a state-afforderl evidentiary privilege

should have efficacy in the federal courts. It is clear t,hat the

S,:reech or Debate Clause of the f ederal constj-tution vrould preclud.e .,

the deposition of a member of Congress in an analogous situatj-on.

In Brewster v. United Stat-=s, 408 U.S. 508 (1975), the Court stated,

"ft is beyond doubt that the Speech or Debate clause protects against

the legislative

.a

U.S. at 525. .

I

, -(

. rr1..';..I !#'L

.'J l;

:el

!lJ

t' l.'

inquiry into acts that occur in the regular course

,r, .1

process and into the motivation for those acts.',

of

408

,..t

.'l

.' *'-1.

f .,,lir-'"c

N

-3- , - / rl,';

'l':,{.u.'.

.,rn].l!.,

, , ,..|.,'

1.:fi.

,,i'

', 'In.

.'. 'L..

Defendants acknowledge that even the privilege granted federal

legislators is hounded by countervailinq consideratj-ons, particularJy.

'ix ..

the need for every man's evidence in federal criminal prosecutionlf:;!:;'l'

As Brewster further states, "the privilege is hroad enough ao irr".,r.::r.,

.'::.

the historic independence of the Legislativc Branch . but narrow,-i.

" t.enough to guard against the excesses of those who would corrupt the:.;;

process by corrupting its memhers. " 408 U.S. at 525. Defendant,s i..

-,

,1,

'i-

motion attempts, however, to conceal no "corruption,'. :'

...

'i .. i'. "I{ith the boundaries of the ferleral legislative privilege in .,,1.i1,

mindr w€ turn to the question of the scope of paralle1 state privileges

,'t''whatever their extent and range of applicabllity in state courtr the,,'

United States Suprerne Court has ruled that state privileges v,ill r dt ,

times, yeild to overriding federal interests in federal courts.

United States v. Gill_ocl:, IOO S.Ct. 1Ig5 (1980) . The Court has

recognized only one federal interest of importance sufficient t,o ':

,

merit dispensing with this state-granted privilege: , the prosecution

of f ederal cri-mes.

The Supreme Court has never scluarety addressed the issue presented

here: .whether a state legislator's evidentiary privilege remains

intact in federar civir proceedj-ngs. rn @, =,rpr",i,

the Court ruled that a legislatorrs aybs.lang-ve. immunity from suit,'?:.

withstood ah: enactment of 42 U.S.C. 51983, ancl thus state legislators

were not susceptible to suit for rrords and acts vrithin the purvievl

of the legislative process. Although it deals r+ith the substantive ' .

aspect of the privilege, Tenney is instructive, insofar as t,he Court

there gave great dcference to the statets own doctrine. Recently,

i" llitea stat"s v. (;i}o.E, supra, a criminal case invoLving the

,:evidentiary facet of legislative immunity, the Corrrt cited Tenney

forthepropositignthqta11federaIcourtsmustendeavortoaPp1y

state legislative privilege. In GiIIock, however, the Court ruled

,'^

-

{ri ,

I

\

that the Tennessee Speech or Debate C1ause would not exclude

inquiry into the legislatj-ve acts of the aefJndant-legislator

prosecuted for a federal criminal offense.

Throughout tl'rc Supreme Court's activity in this field no

Congress j-onaI

for themselves

,,

.

,'

].::

.,:1.(

- 4--r," +:,'

' :i dr.''1"'J t

.:i,

'' A. 1.,.,

' rrt{:.

.il'*-"

,i>''. li r

reanportionmen

{.

. Insofar ,as

distinction has been drawn betvreen substantive and evidentiary .. ,i''l"

applications of the privilege for the purpose of determining the

,,:: l.

.lt _.efficacy of legislative privileqe in federal court. Thus, the i

.. \.

Court's conclusions in gillgck and Tgnsy must be read togetherr'','l'

,;

and tl:eir comhined ef fect dictates that the evidentiary prj.vilege i':

1,. ,

granted a legislator by his state remains inviolahle except where:,1.:,.,, ,,V,F:i

it must yield to the enforcement of federal criminal statutes. ,dre es es'-- '

, ll J'

Sce Gillocl: at 1193 ':'t''.'.

Un1ess federal criminal prosecution demands othen'rise, "the

role of the state legislature is entitled to as much judicial

respect as that of Congress . The need for a Congress rahich may '

(-

act free of interference by the courts is neithe:: more nor less than

the need for an unimpaired state legislature. " Star Distributors, Ltd

v. Mari-no, 613 F.2d 4 (1980) at 9. On this fundamental point the

Supreme Court has recently said, "To create a system in wlrich the

a

Bill of Rights monitors more closely the conduct of state officials

than it does that of federal officials is to stand the consti-t,ut,ional

design on its head." P"!Z_y:_ gcgqomou, 428 tl.S. 478 (1978) at 504.

fn the .present civil action, brought by private citizens of

Ilorth CaroIina, Leqislators l{arvin and Rauch are privileged to refuse

to testify concernins their legislative acts. Principles of comity.

and the decided law strongly suggest that federal courts honor this

evidentiary privilege in aIl civil actions

II. TI.IE I.IATER]AL SOUGIIT TO BE DISCOVERED IS IRRELEVA}IT.

The North Cago1iXa House, Senate, and

plans challenged in this litigation speak

,

r\*

,.. ,'.r,i

'

'

.t,.,

trr.)

,.r,;i,.:,i-r

' lr.

' .''.lt ..i

, . '.- -!q;*!rre*

the intent of the legisl-ature is in question, the legislative history,

i'e., the conteml>oraneous record of dehate .ie. enactment, tulr"a1"t tna

"'' '' i. .Iegislative intent. The remarks of any single legislator, even thei,i,

''..., i.i

{.i.if,r,sponsor of the bi11, are not controlling in analyzing Iegislative,,,",

history. Chrysler Corpo{ation rz. Brown , 441 U.S. 2g1 (tgl9) . ft.til

such remarks have any relevance at all precludes that they were made

"{: i,,/ l

contemporaneously and constitute part of the record. See United l'',,",

.;ti$;

State v. Gila River pima-ltaricopa_Indian Community, 5gO F.2d 2Og 1.'

(ct' cl' 1978). This proposition is adherecl to even more strongly;.'

by the appellate courts of North carolina. The North Carolina Supq,emg

' ' '.:.'Court, for example, stated the following in D & w,-.rnc. v. Charlotterlt:

268 N.C. 577 , 581, 151 S.E.2d 24L, 244 (1966) :

". I.,lore than a hundred years ago tl-ris Courtherd that 'no evidence as to the motives of theLegislature can be heard to give operation to t otto take it from, their acts. . Dral<e v. Drake,15 N.c. 110, rr7. The meaning of a sEEEuEe--anilEhe'intention of the legislature which pas.serl it cannotbe shorvn by the testimony of a memher of the legisla_ture, it 'must be drarvn from the construction oi theAct itself .' Goi_ns v. fndian Training School , l-69N.C. 736, 739, B6 s.E.--07g, 0grl

'! .:

, r'.\

The testimony of Marvj-n and Rauch is

of the peneral Assembly and can have no

Thus, their depositions are outside the

discovery.

II]

not relevant to the intent,,

other discernable relevance.

scope of permissible

PRESERVATTON OF LEGISLATIVE INDEPENDENCE REQUIRES T}IAT, .SHOI.ILDtTiE pEp osr 1rI6NS-pRoCEED Lr-

If the court orders the deposi-tions to procee<l, it is imperative

that the transcripts he sealed and opened only upon Court Order. The

purpose of legislative privirege is to ,'avoid intrusion by the

Executive or the Judiciary into the affaj-rs of a co-equal hranch,

and - to protect legislative inrlependence." Gillock at II91.

a

t

.,| It

{

t

- 6-.

Legislators must f ee1 f ree to discuss anQ,. ponder the pletfrora,',;ilj'.

of economic, social, and political considerations which enter into'Liit,

oi}itlY,,

legislative decision-making. Pear of subsequent disclosure of arl"lfj'.",'

individual legislator's intent or rationale tvouLd chil1 <lebate

"rrq;'::.;'

destroy independence of thought ancl vote. In this case, sensitivq ;t

political considerations might be recklessly exposed by the Plaintiff.'t

proposed discovery. To maintain free expression of j.deas vrithin qh"l',,iil:

General Assembly, as well as to protect those ideas already freelyiilT

1:. l.:

cxpressed therein, a protective order must issue, if the suhrpoenaqjjfi,

are not quashed, as theY should be.

P.UFUS L. EDI,{ISTEN

ATTORNEY GNI'IERAL

Jam-

Attorney Gene

LegaI Affairs

rney Generalrs Office

. C. Department of Justice

Post Office Box 629

P.a1eigh, I.lorth Carolina 27602

Telephone: (919) 733-3377

Norma Harrell

Tiare Smiley

Assistant A.ttorneYs General

John Lassiter

Associate AttorneY General

Attorneys for Defendants

Of Counsel:

Jerris Leonard & Associates, P.C

900 17th Street, N.I{.

Suite 1020

Washington, D. C. 20006

Q02) 87 2- 109 s

'i)/

:t" 'i,,'t' .,'

'i !:'..,i ,. tl'_'t:,) i,

l;:. tr.

,;'

\\^

\

I

!,,

not quashed, as they should be. ,t'X,tffi*-..

Respectfully su):mitted, this L,," /( day of December, 1981. :ffij: