Chisholm v. United States Postal Service Brief for Appellee

Public Court Documents

October 2, 1976

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Chisholm v. United States Postal Service Brief for Appellee, 1976. 0c7c1b6e-ad9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b78c0a79-5ccb-4a40-9622-b7224be7ebef/chisholm-v-united-states-postal-service-brief-for-appellee. Accessed February 28, 2026.

Copied!

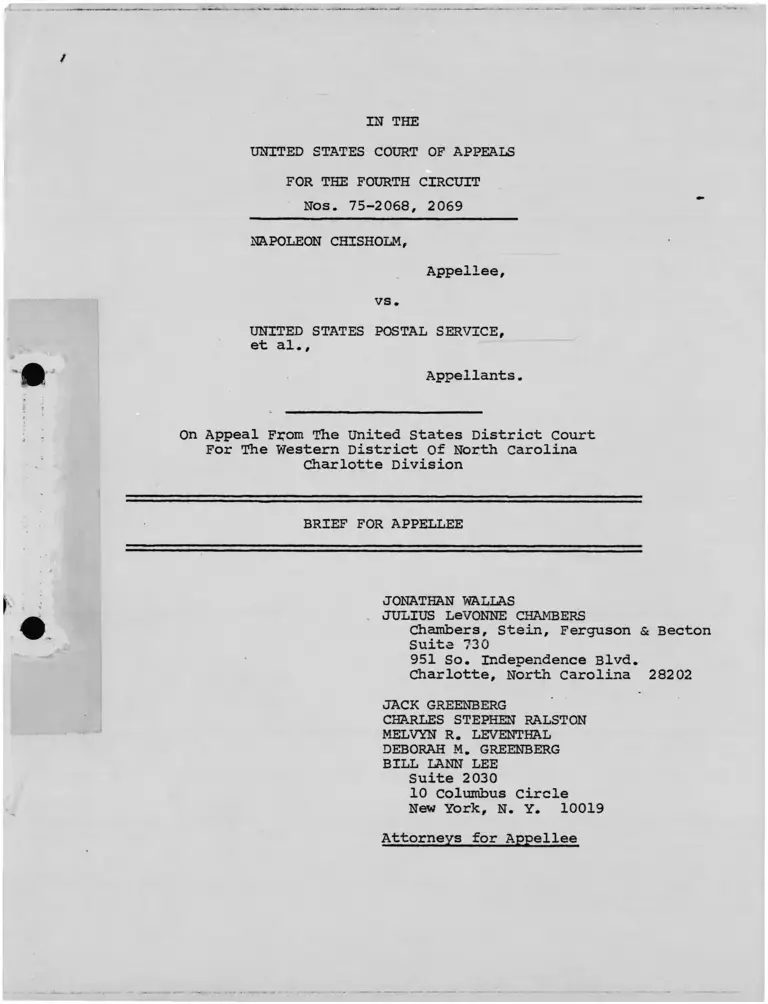

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 75-2068, 2069

NAPOLEON CHISHOLM,

Appellee,

vs.

UNITED STATES POSTAL SERVICE,

et al.,

Appellants.

On Appeal From The united States District Court

For The Western District Of North Carolina

Charlotte Division

BRIEF FOR APPELLEE

JONATHAN WALLAS

JULIUS LeVONNE CHAMBERS

Chambers, Stein, Ferguson & Becton

Suite 730

951 So. Independence Blvd.

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

JACK GREENBERG

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

MELVYN R. LEVENTHAL

DEBORAH M. GREENBERG

BILL LANN LEE

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

Attorneys for Appellee

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Table of Contents ............................ .

Table of Authorities ...............................

Statement of Issues Presented .....................

Statement of the Case ..............................

A. Administrative Proceedings ..............

B. Judicial Proceedings ....................

Statement of Facts ................% ...............

A. Discriminatory Denial Of Plaintiff

Chisholm's Applications .................

B. Discrimination Against Black Employees

Generally ................................

1. Discriminatory Policies and

Practices ..........................

> 2. Prima Facie Discrimination ........

Argument

Introduction ..................................

I. A Class Action Was Properly Certified

Pursuant To Rule 23(a) and (b)(2),

Fed. R. Civ. Pro.........................

A. Class Actions Provided For In The

Federal Rules Of Civil Procedure .

Are Not Precluded By The Statutory

Language Of 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16 ...

1. Rule 23(b)(2) Fed. R. Civ.Pro............................

2. 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16 .........

B. The Legislative History Of the

1972 Amendment To Title VII

Demonstrates Congressional

Intent To Allow Rule 23 Class

Actions ............................

1

iii

1

2

3

9

12

13

16

16

18

Page

21

27

33

34

36

41

-l-

1. Legislative History ........... 41

2. Case Law ...................... 48

C. The Administrative Process Does

Not Permit Class Claims To Be

Accepted, Investigated Or

Resolved Effectively ............... 57

1. 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16 ........... 58

2. 5 C.F.R. Part 713 As Applied .. 60

D. The Broad Provisional Definition

Of The Class Was Proper ............ 65

II. Intervention Was Properly Permitted

Pursuant To Rule 24, Fed. R. Civ. Pro. .. 70

Conclusion ........................................ 70

Appendix A ....................................... la- 7a

Appendix B ........................................ lb- 5b

Appendix C ........................................ lc-32c

Appendix D ........................................ ld-27d

Page

- l i -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

Cases:

Aetna Ins. Co. v. Kennedy, 301 U.S.

389 (1937) ....................................

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S.

405 (1975) .................. 21, 25, 36, 41,

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415

U.S. 36 (1973) ..................

B. A. R. Decision No. 713-73-593 ................

Barela v. United Nuclear Corp., 462 F.2d

149 (10th Cir. 1972) .........................

Barnett v. W.T. Grant Co., 518 F.2d

543 (4th Cir. 1975) .......................

Barrett v. U.S. Civil Service Commission,

69 F.R.D. 544 (D.D.C. 1975) ............ 29,

52,

Blue Bell Boots Inc. v. EEOC, 418 F.2d

355 (6th Cir. 1969) ..........................

Bowe v. Colgate-Palmolive Co., 416 F.2d

711 (7th Cir. 1969) ..........................

Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing Machine Co.,

457 F.2d 1377 (4th Cir. 1972), cert. denied,

409 U.S. 982 (1972) ..........................

Brown v. General Services Administration,

44 U.S.L.W. 4704 .............................

Chandler v. Roudebush, ____ U.S. ____ ,

44 U.S.L.W. 4709 (Sup. Ct. June 1, 1976) 12,

Coles v. Penny, 531 F.2d 609 (D.C. Cir. 1976)

Contract Buyers League v. F & F Investment

Co., 48 F.R.D. 7 (N.D. 111. 1969) .......

Danner v. Phillips Petroleum Co.,

447 F .2d 159 (5thCir. 1971) ..............

40

00V 52, 53, 55

26, 34, 40, 41

63

42

23, 35, 66, 67

30, 31, 36, 41

53, 61, 62, 65

69

22, 42, 57

23

12, 39, 47, 48

21, 24, 25, 26

28, 30, 33, 34

40, 47, 48, 49

24

67

69

Day v. Weinberger, 530 F.2d 1083

(D. C. Cir. 1976) ...........

- l i i -

24

Page

Cases (cont'd)

Dillon v. Bay City Construction Co., 512

F .2d 801 (5th Cir. 1975) ..............

Douglas v. Hampton, 512 F.2d

976 (D.C. Cir. 1975) ..................

EEOC v. University of New Mexico, 504

F .2d 1296 (10th Cir. 1974) ...........

Ellis v. Naval Air Rework Facility, 404

F.Supp. 391 (N.D. Cal. 1975) ......... 29, 38, 51, 56, 60, 64

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co.,

U.S. . 47 L.Ed. 2d 444 (1976^

36’ 41) 48

53, 55

Gamble v. Birmingham Southern Ry. Co.,

514 F .2d 678 (5th Cir. 1975) .........

Georgia Power Co. v. EEOC, 412 F.2d 462

(5th Cir. 1969) .......................

Graniteville Co. v. EEOC, 438 F.2d 32

(4th Cir. 1971) .......................

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S.

424 (1971) ............................

Grubbs v. Butz, 514 F.2d 1323

(D.C. Cir. 1975) ......................

Hackley v. Roudebush, 520 F.2d 108

(D.C. Cir. 1975) ................... 24, 28, 36, 41, 56, 60

Hariiis v. Nixon, 325 F.Supp. 28

(D. Colo. 1971) .......................

Hodges v. Easton, 106 U.S. 408 (1882) ___

Jenkins v. United Gas Corp., 400 F.2d

28 (5th Cir. 1968) .................... 22, 35, 41, 42, 43

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, Inc.,

417 F .2d 1122 (5th Cir. 1969) ........

Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 U.S. 458 (1938) ... ..... 40

Keeler v. Hills, 408 F.Supp. 386

(N.D. Ga. 1975) ...................... 29, 36, 52, 60, 64, 67

Koger v. Ball, 497 F.2d 702

(4th Cir. 1974) .......................

-iv-

Page

Lance v. Plummer, 353 F.2d 585 (5th Cir. 1965), cert.

denied. 384 U.S. 929 (1966) ................... 37,38,39

Local No. 104, Sheet Metal Workers Int'l.

Assoc, v. EEOC, 429 F.2d 237 (9th Cir. 1971)... 69

Long v. Sapp, 502 F.2d 34 (5th Cir. 1974) ....... 67

Love v. Pullman Co., 404 U.S. 522 (1972) ......... 32,40

McBroom v. Western Electric Co., 7 EPD f9347

(M.D. 1974) .................................... 70

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792

(1973) 25,34,40

McKart v. United States, 395 U.S. 185 (1969) .... 49

McLauthlin v. Callaway, Fifth circuit No. 75-2261,

reversing position taken in, 382 F. Supp.

885 (S.D. Ala. 1974) ........................... 30

Macklin v. Spector Freight System, Inc.,

478 F .2d 979 (D.C. Cir. 1973) ................. 42

Miller v. International Paper Co., 408 F.2d

(5th Cir. 1969) .................. 42-

Morrow v. Crisler, 479 F.2d 960 (5th Cir. 1973),

aff'd en banc. 491 F.2d 1053 (5th Cir. 1974)... 23,57

Morton v. Mancari, 417 U.S. 535 (1974) ........... 24,56

Moss v. Lane Co., 471 F.2d 853 (4th Cir. 1973) ... 23

Motorola, Inc. v. McClain, 484 F.2d 1139 (7th

Cir. 1973), cert, denied. 416 U.S. 936 (1974).. 69

Newman v. piggie Park Enterprises, 390 U.S. 400

(1968) ......................................... 39

New Orleans Public Service, Inc. v. Brown, 507

F .2d 160 (5th Cir. 1975) ...................... 69

Oatis v. crown Zellerbach Corp., 398 F.2d 496

(5th Cir. 1968) ...................... 22,37,39,41,43

48,56,57,70

Ohio Bell Telephone Co. v. Public Utilities

Comm., 301 U.S. 292 (1937) .................... 40

Cases (cont'd)

-v-

Page

Parks v. Dunlop, 517 F.2d 785 (5th Cir. 1975) .... 24

Pendleton v. Schlesinger, 8 EPD f 9598

(D.D.C. 1974) .................................. 28

Place v. Weinberger, __ U.S. __, 44 U.S.L.W. 3718

(Sup. Ct. June 14, 1976), vacating, 497

F.2d 412 (6th Cir. 1974) ........................ 24

Predmore v. Allen, 407 F. Supp. 1053 .... ....... 28,29,36,49

(D. Md. 1975) 52,53,60

Richerson v. Fargo, 61 F.R.D. 641 (E.D. Penn.

1974) ........................................... 29,36

Robinson v. Lorillard corp., 444 F.2d 791,

cert, dismissed, 404 U.S. 1006 (1971) .......... 42

Rodgers v. U. S. Steel Corp., 69 F.R.D. 382

(W.D. Penn. 1975) .............................. 67

Sanchez v. Standard.Brands, Inc., 431 F.2d

455 (5th Cir. 1970) ............................ 40,69

Sharp v. Lucky, 252 F.2d 910 (5th Cir. 1958) .... 37,39

Sibbach v. Wilson & Co., 312 U.S. 1 (1941) ...... 33

Simmons v. Schlesinger, No. 75-2182 argued

May 3, 1976 .................................... 29

Sosna v. Iowa, 419 U.S. 393 (1975) (White J.

dissenting)..................................... 23

Sylvester v. U. S. Postal Service, 393 F. Supp.

1334 (S.D. Tex. 1975) ......................... 29,36,60

United States v. Allegheny-Ludlum Industries,

Inc., 571 F.2d 826 (5th Cir. 1975) ........ . 56

United States v. Chesapeake and Ohio Ry. Co.,

471 F.2d 582 (4th Cir. 1972) .................. 22

United States v. Georgia Power Co., 474 F.2d

906 (5th Cir. 1973) ............................ 22

Weinberger v. Salfi, 422 U.S. 749 (1975) ........ 38,52,54

Williams v. Tennessee Valley Authority,

415 F. Supp. 454 (M.D. Term. 1976) ___ 29,36,41,50, 52

53,55,56,61,64

Cases (cont'd)

-vi-

Page

Wilson v. Monsanto Co., 315 F. Supp. 977

(E.D. La. 1970) ................................. 67

Zahn v. International Paper Co., 414 U.S.

291 (1973) ..................................... 52,53,54

Statutes, Rules and Regulations;

28 U.S.C. § 1292 (b) ............................... 10,65

28 U.S.C. § 1331 9

28 U.S.C. § 1332 (a) ............................... 52

28 U.S.C. § 1343 (4) ............................... 9

28 U.S.C. § 2072 ................................. 33

28 U.S.C. § 2073 ................................. 33

28 U.S.C. § 2201 ................................. 9

28 U.S.C. § 2202 ................................. 9

42 U.S.C. § 405(g) ................................ 38,53

42 U.S.C. § 1981 ................................. 9,11,12

42 U.S.C. § 1983 ................................. 37

42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e, et seq.......................... 65

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5 ......................... 21,22,33,34,39

41,45,46,48,49

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5 (f) ........................... 45,48

41 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(f) (1) ..................... ».. 45

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16 ........................ 1,2,9,21,23,26

32,33,36,38

39,40,41,45, 58

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16 (a) ............................ 58,59

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16(b) ............................ 59

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16(c) ........................ 39,45,47,49

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16(d) ......................... 22,45,47,49

Cases (cont'd)

-vii-

Statutes, Rules and Regulations, (Cont'd)

Civil Rights Act of 1964

. Title Jl ....____ ............................... 37

§ 706 Title-VII.......... 21,43

§ 706<a)........................ 42

§ 706(b)......................................... 42

§ 706(d)......................................... 42

§ 706 (f)(1)...................................... 45

§ 706(f)- (k) . ..................................... 45

Rule 23, Fed. R. Civ. Pro..................... 12,22,26,33,34

38,40,41,49

Rule 23(a), Fed. R. Civ. Pro.................. 2,9,26,27,32,34

Rule 23(b)(2), Fed. R. Civ. Pro................... 2,9,26,27

32,34,35,36

Rule 23(c)(1), Fed. R. Civ. Pro................... 27,66

Rule 24, Fed. R. Civ. Pro......................... 3,12,27,70

5 C.F.R. Part 713 ................................. 3,58,60,64

5 C.F.R. §§ 713.211 et seq........................ 61

5 C.F.R. § 713.251 ................................. 64

41 F.R............................................... 31

Legislative History

H. R. 1746 .......................................... 42,45

Hearings Before the Subcomin. on Labor of

the H. Comm, on Education and Labor,

92d Cong., 1st Sess. (1971) ...................... 25

Hearings Before the Subcomm. of the S. Comm,

on Labor and Public Welfare, 92d Cong., 1st

Sess. (1971) ..................................... 25

Legislative History of the Equal Employment

Opportunity Act of 1972 ................... ..;... 42,43,44

45,47,59,69

S. Rep. No. 92-415, 92d Cong. 1st Sess (1971)...... 25

118 Cong. Rec...................................... 45

Page

v m

Page

Other Authorities

K. Davis, Administrative Law § 20.07.................... 60

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission,

Eighth Annual Report for FY 1973 ..................... 56

Federal Practice And Procedure, Civil § 1785

(1st ed. 1972) ........................................ 68

Proposed Amendments to Rules of Civil Procedure,

39 F.R.D. 69 (1966) ................................... 35

7A Wright & Miller; Federal Practice And Procedure,

Civil § 1785 (1st ed. 1972) ......................... 67

U. S. Commission on civil Rights, The Federal

Civil Rights Enforcement Effort, 1974 Vol. V 56,61

'Civil Rights Act 1964, 84 Harv. L. Rev. 1109 (1971).. 42

Development in the Law, Employment Discrimination

And Title VII of the civil Rights Act of 1964,

84 Harv. L. Rev. (1971) ............................. 42

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 75-2068, 2069

NAPOLEON CHISHOLM,

Appellee,

v s .

UNITED STATES POSTAL SERVICE,

et al.,

Appellants.

On Appeal From The United States District court

For The Western District Of North Carolina

Charlotte Division

BRIEF FOR APPELLEE

Statement Of Issues Presented

1 ,

In this civil action brought by a black federal employee

to redress pervasive policies and practices of racial discrimi

nation in agency employment practices pursuant to, inter alia.

Jl / Under 42 U.S. C. § 2000e-16, emplovees of the united States

Postal Service are federal employees'for all relevant purposes.

§ 717 of Title VII of the civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended,

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16:

1. Whether the district court properly allowed the

action to proceed as a class action pursuant to Rule 23(a)

and (h)(2), Fed. R. Civ. Pro.?

2. Whether the district court properly permitted inter

vention in the action by five other black employees pursuant

to Rule 24, Fed. R. Civ. Pro.?

_2/

Statement Of The case

This is a federal employee Title VII action for declaratory

and injunctive relief against across-the-board racially discrimi

natory employment policies and practices at the Charlotte,

North Carolina branch of the United States Postal Service

(hereinafter USPS Charlotte"). Plaintiff is Napoleon Chisholm,

a long time black employee of USPS Charlotte , then employed

as a mail carrier PMS-5. He brought the action on his behalf

and on behalf of all other similarly situated persons after

unsatisfactory administrative resolution of a substantiated

charge of racial discrimination. Defendants are the united

States Postal Service and certain postal officials who are %

responsible for maintaining the employment policies and prac—

tices complained of.

_2/ Citations are to the Appendix, hereinafter "A."- the Record

on Appeal, hereinafter "R.".y and the Administrative Record that

was made part of item 6 of the Record on Appeal (See A. 1) here

inafter "R. 6 Admin, r ."

_3/ W. A. Shaw, officer in charge of USPS Charlotte; E. T. Klassen

Postmaster General of the united States; and Michael R. Greeson.

Director of Personnel of USPS Charlotte.

2

A. Administrative Proceedings

plaintiff Chisholm filed a formal administrative complaint of

racial discrimination pursuant to U. S. Civil Service Commission

regulations set forth at 5 C.F.R. Part 713, attached hereto as

4_/

Appendix A, infra. (A. 64-65). As is true throughout the

entire administrative process Mr. Chisholm was not represented

by counsel. The complaint states that the "specific action or

situation complained of" is:

3. (a) On March 4, 1972, the position of

Finance Examiner, level 9 was filled by

Mr. Robert L. Wallace and on March 13, 1972,

the position of Budget Assistant, level 8 was

filled by Mr. L. B. Holland; I was denied an

equal opportunity to be considered for the

above positions.

(b) That such denial of equal opportunity for

black employees in relation to promotion in

the U. S. Postal Service, Charlotte, N.C. is

a continuing discriminatory practice.

(A. 64). Mr. Chisholm gave as "the date of the alleged act of

discrimination," " [s]pecifically: March 4, 1972 and March 13,

1972" and " [g]enerally: 1960 through present time." The

following were set forth as reasons to believe there was

discrimination:

7. In being denied the equal opportunity to be

considered for the aforementioned positions, I

was informed by the Personnel Office that I

did not meet the specialized experience required,

in that, at least one year of specialized

experience must have been at a level of difficulty

comparable to not more than 3 levels and 2 levels

On March 30, 1972, after inconclusive informal proceedings,

4 / The complaint is a letter which follows the format prescribed In Postal Service regulations implementing 5 C.F.R. Part 713. The

format is set forth in Brief For The Appellants 3 n. 2.

below the position to be filled, 9 and 8 respect

fully [sic]. Therefore, since I am a level 5

carrier I was denied the opportunity to compete

for the positions. However, in subsequent adver

tisements with the same stipulation above;

Mr. C. C. Claud and Mr. Leonard W. Kerr, both

level 5 and both white employees were granted

an opportunity to compete for level 8 positions

on March 10, 1972 at 10:30 a.m. and 11:00 a.m.,

respectively [sic]. On March 17, 1972, Mr. Jack

R. Polk, a white employee, level 4 was granted

an opportunity to compete for a level 8 position

advertised with the same stipulation.

Therefore, I contend that the aforementioned

stipulation is a manipulated tool of management

whereby discrimination in general is practiced

by management against the black employees and

in this case specifically against me. In that

I firmly believe that I am the more qualified

employee.

In regards 3-b above: because of the lack of

the accessibility to record examination the

below contentions are not based on specific

statistics, however they are in my opinion,

statistically inferred based on 12 years of

competent observation - stated within a 95% to

99% competence level.

(a) That less than 1% of the total supervisory

staff, level 7 and above is black.

(b) That the total number of black supervisors

appointed since 1960 is less than h of 1%

of the total number of white supervisors

appointed since 1960.

(c) That the total number of times that a

black supervisor has chaired a position on

the Promotion Advisory Board is less than

h of 1% of the total number of times that

it has convened.

(d) That the white employee has been consistently

"detailed" to the open positions and allowed

to work in the position on an average of

1 year before it goes up for bid, thus

giving the "detailed" employee a definite

advantage over any other applicant.

(e) That the "detailed" employee gets the

position regardless of the qualification

of any applicant competing against him.

(f) That less than h of 1% if any, black

employees, are "detailed" to supervisory

and other staff positions.

As a result, it is through the "detailed process"

which is unadvertised, and the convening of a

biased Promotion Advisory Board that willful and

consistent discriminatory practices in promotions

against the black employee, has and is prevailing

in the Charlotte, N. C. Postal Service.

(A. 64-65). The district court found that, "[i]t is undisputed

that . . . in his formal complaint, the plaintiff raised broad

class-wide issues of discrimination" (A. 37).

As required by U. S. Civil Service Commission regulations,

an investigation was conducted by an investigator employed by

_!/the Postal Service. On the basis of a review of the investi

gator's report and considering only the denial of Mr. Chisholm's

applications for promotion, the regional USPS Office of Equal

Employment Compliance issued a proposed decision that the

"allegation of discrimination due to your race is not supported;

therefore we propose to dispose of your complaint of discrimination

5/ The investigator's report and attached exhibits are set forth

in’ R. 6, Admin. R. 40-110. While the investigation apparently

focused on the specific denial of the two promotions, the following

exhibits pertain to discrimination against black employees

generally: "No. 5: May 1971 Minority Census Report for the

Charlotte, North Carolina Postal Installation" (A. 66); "No. 6:

Field Report on EEO Program for Progress (POD Form 1789) for the

period of December 1, 1970 to May 31, 1971" (A. 67-68); "No. 7:

Field Report on EEO Program for Progress (POD Form 1789) for the

period of May 31, 1971 to November 30, 1971" (A. 69-70); "No. 8:

Analysis of Promotions made within the Post Office Branch of the

Charlotte, North Carolina Postal Installation during the period

of April 1, 1971 to March 31, 1972;" "No. 10: Applications of

white level PS-5 personnel considered for the position of Safety

Assistant, PMS-8 and copy of posting of the position dated

February 18, 1972;" "No. 11: Application of white level PS-4

employee considered for the position of Training Assistant,

PMS-8 and copy of posting of the position dated February 23, 1972"

(R. 6, Admin. R. 43-44, 56-72, 86-110).

as not being supported" (R. 6, Admin. R. 33). Mr. Chisholm

was informed that he could request an administrative hearing

if dissatisfied with the proposed decision, and he did so

(R. 6, Admin. R. 32). A hearing was held September 21, 1972

at which some evidence of class-wide discrimination was presented.

In his recommended decision, the hearing examiner considered

only " [hasp the complainant been improperly denied consideration

for promotion?" (A. 56). The examiner found "that the complainant

was improperly denied consideration for the position of Finance

Examiner, but that he was not improperly denied consideration

for the position of Budget Assistant" (A. 61-62), and recommended

that, "The preponderence of the evidence supports the allegation

of discrimination because of race" (A. 62). Thereupon

_6/

6/ The transcript and exhibits are set forth at R. 6 Admin. R.

118-233.

7/ See infra at 14-16, 18-20, see also A. 71.

8/ The following was the recommended relief:

Since the evidence shows an inconsistency in the

application of the qualifications standards by the

Personnel Office of the Charlotte Post Office, it is

recommended that for at least one year, all determi

nations of eligibility and/or ineligibility of candi

dates for positions in the Charlotte Post office be

audited by the Regional office before the lists of

eligibles are referred to the selecting official.

It is also recommended that the complainant be given

priority consideration for promotion to the first

available position for which he applies in which he

meets the minimum qualifications.

(A. 62).

6

on December 29, 1972, the national office of USPS Equal

Employment Compliance accepted the examiner's proposed findings,

recommended decisions and recommended action in a short letter

of final decision (A. 63). The letter also did not address

allegations of class-wide discrimination. Mr. Chisholm was

given the option of appealing to the Board of Appeals and

Review of the U. S . Civil Service Commission (presently the

Appeals Review Board) or filing a civil action pursuant to

Title VII; he chose the former (A. 52-54).

Mr. Chisholm's January 14, 1973 letter of appeal states;

After careful consideration of the various

factors leading to his decision, I have

concluded that I cannot and will not accept

his decision. Therefore, on behalf of all

of the minority employees in the Charlotte,

N. C. Post Office and myself I am appealing

to you for equitable relief from the practices

of discrimination against the minority employees

by management in the Charlotte, N. C. Post

Office.

_ V

Among his reasons for appeal were: First, "the decision leaves

intack [sic] an unjustified Promotion Appeals Board which has

only one black supervisor on it; and no female members."

9/ other reasons for appeal were (a) that the- decision wrong

fully omitted the recommended auditing period of "at least one

year" and wrongfully left auditing to the ineffective regional

office; (b) the white employee's promotion to methods and standards

analyst PMS-10, see infra at 14 n. 15, should be declared null and

void; and (c) the promotion of the white employee who previously

had been detailed to and was ultimately selected for the finance

examiner PMS-9 position should be declared null and void and

Mr. Chisholm placed in the position retroactive to March 4, 1972.

7

S econd, " [t]he decision makes no effort to correct the discrimi

nation practices of management via use of the 'detail1 process

(A. 53).

Note: that in the Hearing management made no

effort to defend their method of "detailed"

promotions whereas it was pointed out by me and

testimony given as to just how this is done.

(1) the opening to which they can detail an employee

is not made known to the entire work force, there

fore they hand pick a "buddy," detail him to the

position and allow him to work it for a considerable

length of time, "normally 6 months to a year and

a half," then, they place the position up for bid

as if it just came open. Added to that is the fact

that they load the Promotion Advisory Board with two

people who usually are instrumental in detailing

their "buddy" employee. As a result their "buddy"

gets the promotion. Now place yourself on that

Promotion Board as the third member and you are

reviewing an applicant thats [sic] been working

the position in question for a least a year, and

it has been prior assured that there is no reported

discrepancy in his work performance. How would you

vote?

I am therefore requesting that you direct the

Charlotte Post Office to make known to all employees

of any and all positions to which an employee can

be "detailed" prior to the filling of the position.

And that the Charlotte Post Office allow any and all

employees ample time to express their interest and

qualification for the position prior to filling the

"detailed" position. Your attention is directed

to the fact that when an employee is detailed to a

higher level position he is paid accordingly and its

ultimately the same affect as a promotion.

(A. 53-54). Thereafter on May 29, 1973, the final agency

decision was affirmed except for reimposing the required one

year auditing period (A. 48). The decision expressly stated

that class^wide discrimination would not be addressed (A. 50).

The district court found and it is undisputed that

" [d]espite the clear language in Chisholm's formal complaint,

8

claiming pervasive racial discrimination quoted above, the

administrative agency chose to 'interpret1 Chisholm's complaint

as raising the limited claim of discrimination in the Finance

Examiner and Budget Assistant jobs" only (A. 26). As "the

decision of the Board [was] final and there [was] no further

right of administrative appeal" (A. 51), this lawsuit was

filed on June 27, 1973.

B. Judicial Proceedings

This suit for declaratory and injunctive relief against

racially discriminatory employment practices at US PS Charlotte

prohibited by the Fifth Amendment, 42 U.S.C. §2000e-16 and

42 U.S.C. §1981 was brought in the Western District of North

10/

Carolina, Charlotte Division (A. 4). Mr. Chisholm brought

the action on his behalf and on behalf of all other persons

similarly situated pursuant to Rule 23(a) and (b)(2), Fed. R.

Civ. Pro. The complaint charges that "defendants follow a

policy and practice of discrimination in employment against

blacks on account of their race," and that "the policy and

practice . . . has been and is implemented by the defendants,

among other ways, as follows": refusing to consider plaintiff

Chisholm for promotion to the positions of budget assistant and

finance examiner; maintaining a policy of refusing to grant

promotions to blacks; maintaining a policy of preventing

10/ Jurisdiction of the district court was invoked pursuant to

28 U.S.C. §§ 1331, 1343(4); 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16, 42 U.S.C.

§ 1981 and 28 U.S.C. §§ 2201 and 2202.

9

blacks from attaining supervisory positions; and maintaining

a policy of excluding blacks from the "promotion advisory board"

which has responsibilities for recommending employees for pro-

11/

motion in the USPS Charlotte (A. 6). Thereafter, defendants

filed their answer (A. 13).

On August 22, 1974, five black USPS Charlotte employees -

H. C. Rushing, William J. McCombs, C. A. Rickett, Milton J. Yongue

and James F. Lee - filed a motion to intervene as parties

plaintiff which alleged, inter alia, that they have been denied

promotion and other employment opportunities by the defendants

on account of their race; and that they have an interest in the

business and transactions and policies which are the subject of

the action and are so situated that the disposition of this action

may, as a practical matter, impair or impede their ability to

protect their interests in the action (A. 19). Attached thereto

was a complaint in intervention which generally incorporated the

allegations in the complaint.

In a supplemental memorandum filed October 18, 1974,

defendants renewed their objections to the action proceeding

as a class action because, first, a trial de_ novo is impermis

sible and, second, exhaustion of adminstrative remedies by

members of the class was lacking (R. 29). Defendants also objected

to intervenors' motion because of lack of exhaustion of administra

tive remedies by intervenors. A hearing on all pending motions

11/ On March 5, 1974, the district court decided several pending

motions (A. 12), including, inter alia, (1) denial of defendant's

motion to dismiss (A. 9); (2) allowing plaintiff's motion to compel

answers to plaintiff's first interrogatories; and (3) permitting a

full hearing on the factual issues, i.e., trial de novo.

10

was held December 13th and the lower court issued a memorandum

opinion and order May 29, 1975 (A. 24). The district court

ordered that, inter alia, (1) the action proceed as a trial de_ novo

as in private employee Title VII actions; (2) the action proceed

under 42 U.S.C. § 1981 as well as Title VII; (3) the action be

12/

certified and allowed to proceed as a class action; and (4)

the intervention be allowed (A. 42-43). The opinion specifically

rejected the government's trial de novo and lack of exhaustion

contentions against class action and intervention, choosing

instead to apply recognized Title VII law developed in private

employee actions to decide these procedural questions (A. 35-40).

The district court certified the trial de_ novo, class

action and intervention issues for an immediate interlocutory

appeal to this Court pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1292(b) (A. 42) and,

subsequently, the additional issue of whether the remedy avail

able to federal employees under Title VII is exclusive and thus

preempts other available remedies (A. 45). On August 8 and 13,

1975, the petition for leave to appeal the four issues was

granted and the appeal permitted by this Court. Later, briefing

12/ The class was defined as consisting conditionally of all

black persons who are employed or might be employed by USPS

Charlotte limited, classified, restricted, discharged, excluded

or discriminated by defendants in ways which deprive or tend to

deprive them of employment opportunities and otherwise affect

their status as employees or applicants for employment or pro

motion because of their race or color.

The government's brief fails to acknowledge that the lower

court's definition of the class "is conditional and may be modified

at any stage prior to final determination of the action on the

merits" (A. 43), see pp. 9, 25-32 of the government's brief.

11

■was deferred until the Supreme Court's decision in two pending

cases. On June 1, 1976, the Supreme Court decided that federal

employees are entitled to the same right to a trial de_ novo as

private employees under Title VII in Chandler v. Roudebush,

44 U.S.L.W. 4709, and that Title VII is the exclusive remedy

for federal employment discrimination in Brown v. General

Services Administration, 44 U.S.L.W. 4704, thereby pretermitting

independent consideration by this Court of the trial de novo

13/

and exclusive remedy issues.

The class action and intervention questions, which raise

important issues concerning whether Rule 23 and 24, Fed. R. Civ.

Pro., procedures which safeguard effective judicial enforcement

of Title VII rights of private and state or local government

employees are unavailable to federal employees, remain to be

considered and decided.

Statement of Facts

The district court held that, "This Court's conclusion

that its discretion should be exercised to grant this case class

action status is supported by the fact that (1) the appropriate

administrative agency has limited through 'interpretation'’ its

review of plaintiff's formal complaint to only some of the

discriminatory charges contained therein, thus making it difficult

if not impossible for Chisholm to raise class issues except in

13 / Plaintiff Chisholm agrees with the government that the

dTstrict court's decision permitting a trial de novo should be

affirmed in light of Chandler v. Roudebush, supra, and that the

decision that this case may proceed under 42 U.S.C. § 1981 should

be reversed in light of Brown v. General Services Administration,

supra.

12

this forum; and (2) there is some evidence in the record . . .

which suggests there may have been class-wide discrimination in

the Post Office which has left lingering present discriminatory

effects."—

A. Discriminatory Denial Of Plaintiff Chisholm's

Applications

Plaintiff Chisholm has been employed by US PS Charlotte

since 1958, except for two years military service (R. 6,

Admin. R. 74). In early 1972, Mr. Chisholm, then a mail carrier

PMS-5, applied for two accounting positions, finance examiner

PMS-9 and budget assistant PMS-8 (A. 24, 56). Mr. Chisholm's

application for finance examiner was improperly rejected for

failure to meet specialized experience requirements, although

Mr. Chisholm met substitute educational requirements. The

undisputed conclusion of the administrative hearing examiner,

which the agency accepted, was that Mr. Chisholm "had sufficient

college credits to substitute for the required specialized

experience and that he was improperly denied the opportunity to

be considered for the position of Finance Examiner" (A. 58-63).

The administrative record also indicates that the denial of

•^/ Although plaintiff has not had a full opportunity to develop

the merits of the case, facts concerning the denial of plaintiff

Chisholm's applications and patterns of employment discrimination

against blacks generally are established in the administrative

record submitted to the Court by defendants with their motion to

dismiss (A. 1) and in some of the discovery materials already filed

with the Court (A. 1—3). Parts of the administrative record are

set forth in A. 48-75 and the complete record at R. 6, Admin. R.

1-233.

13

Mr. Chisholm's applications has implications for discrimination

/

against black employees generally in several respects.

First, white employees of similar grades whose applications

also did not comply with comparable required years of USPS

specialized experience nevertheless were concurrently granted

the opportunity to compete for positions equal in grade to those

15/

Mr. Chisholm was denied consideration for. The undisputed

conclusion of the administrative hearing examiner, which the

agency accepted, was that "the application of published qualifi

cation standards at the Charlotte Post Office have not been

applied to certain white candidates, but that no deviation from

the standards were granted in consideration [Mr. Chisholm] for

positions for which he has applied" (A. 62-63).

Second, Mr. Chisholm's assertion that the white employee

ultimately selected for finance examiner was unfairly preferred,

preselected and qualified by supervisors who had previously

"detailed" him to the examiner position, is supported by the

testimony of another witness, _ unrebutted and uncontradicted in

16/

the administrative record.

15/ Thus, a white PMS-4 employee was determined to be eligible

for consideration for training assistant PMS-8 without any

specialized experience or substitute education (A. 59-60); a white

PMS-6 employee was considered eligible to compete and ultimately

selected for methods and standards analyst PMS-10 without any

specialized experience and on the improper basis of a test (A. 60-61)

two white PMS-5 mail clerks were determined to be eligible for

consideration for safety assistance PMS-8 on the basis of non-

Postal Service experience (A. 58-59); and a white letter carrier

was improperly considered for safety assistant PMS-8 on the basis

of an insufficient detailed reference to previous employment

experience (A. 61).

R. 6, Admin. R. 182-184.

14

It was and still is my contention that I am a

better qualified employee than Mr. Robert

Wallace for Finance Examiner position level 9.

Management made no effort to refute my

position or to defend Mr. Robert Wallace's

qualifications. However, I pointed out and

testimony given that Mr. Wallace was a level

5, that his position was reranked to level 6,

shortly thereafter he was given a level 7 job

which he never worked, and was then detailed

to level 9 Finance Examiner position for a

year and three months before it went up for

bid. And that the same two people who were

instrumental in detailing him as well as manip

ulating him on paper, to the various positions

were the same two people who were on a three

man Promotion Advisory Board which I was not

allowed to appear before. Those two people

were Mr. Carl Sims his immediate supervisor in

finance and Mr. Harold R. Kennedy, Director.

Gentlemen that was plainly a bias [ed] Promotion

Board and a "buddy" system of Promotion.

(A. 54). " [B]efore 1972 there were few, if any, black clerks or

carriers detailed to higher level jobs" (A. 75). The hearing

examiner, however, failed to address the question of the

discriminatory impact of specialized experience requirements

on Mr. Chisholm or other black employees' promotional

opportunities in light of whites-only detailing.

Third, USPS Charlotte promotion advisory boards which con

sidered, inter alia, the applications for both the finance

examiner and budget assistant positions were constituted in a

manner that would limit and in fact did limit the membership

17/

largely to white supervisors. As a result, only one black

supervisor had ever sat on promotion advisory boards at USPS

Charlotte and he only since 1971. Mr. Chisholm's assertions

17/ A. 53; R. 6, Admin. R. 159-163, 213-214.

15

to this effect, although supported by the testimony of

several witnesses, unrebutted and uncontradicted, also were

not reached by the hearing examiner in his recommended decision

B. Discrimination Against Black Employees Generally

1. Discriminatory Policies and Practices

At this juncture, the record is most developed on the

discriminatory impact of detailing.

The heart of Chisholm's (and prospective

plaintiffs-intervenors) claim of racial dis

crimination is the "detailing" process, a

system utilized to fill "temporary vacancies"

in USPS. Details apparently have been given

on the basis of highly subjective criteria.

Plaintiffs contend blacks have been denied

details and, consequently, are presently

disadvantaged with respect to all pending

and future promotions. Promotions in USPS

are based to a great extent on past job

experience and past work at various job

levels. One method by which such experience

is gained is through temporary "details."

Thus, if plaintiff prevails and demonstrates

by the evidence that blacks have been victims

of a racially discriminatory detailing system,

he contends he will further demonstrate that

blacks presently seeking promotions are and

will be disadvantaged because they do not have

job experience or level experience they would

have obtained absent discrimination.

A cursory review of the Administrative

Record in this case and some discovery material

tends to substantiate plaintiff's claims of

discrimination in the detailing process.

James W. Toatley, the EEO Specialist for the

Charlotte Post Office, reported on September

20, 1972: "Before 1972 there were few, if any,

black clerks or carriers detailed to higher

level jobs." The extent and reasons for this

apparent discrimination in the detailing

system were made more clear in [a] . . .

colloquy between counsel for the plaintiff and

Mr. Toatley during Toatley's deposition taken

on November 12, 1974 (pp. 24-29 of the depo

sition:

16

* * *

Q. Do you have any explanation, Mr.

Toatley, as to why a number of blacks

who had college degrees were serving

as clerks and carriers in the Post

Office rather than some higher position?

A. To be factual, I couldn't, you know, I

can't give, you know, other than my own

opinion.

Q. Well, what is that?

A. Well, during Carpenter's administration,

they just weren't hired. I mean they

just — they just didn't put them in

higher levels.

Q. You're saying because they were black?

A. I would say so.

(A. 27-33). See also supra at 14-15 and infra at 20.

There are other indications of class-wide policies and

practices with discriminatory impact that are lurking in the

record. For example, defendants' answers to plaintiff's first

interrogatories suggest that subjective discretion by the almost

all-white supervisory force plays a critical role in at least

two points in the promotion process (R. 24, Answers to Interr.

10-11 at 10-14). Thus, employees who take and pass the super

visory examination, are placed upon a register. The Postmaster

may consider as eligible for promotion any employee who has

attained a score of 55% on the appropriate supervisor examination.

Eligible employees to be considered are then appraised by their

18/

immediate supervisor and rated overall. Written appraisals

18/ Exhibit 5A, attached hereto as Appendix B infra at lb _ 4b.

17

of performance and potential are required in Section B. Factors

to be considered in evaluating performance are "job knowledge,"

"work execution," "job relationships," "job demands," and "job

conduct"; factors to be considered in evaluating potential are

"learning capacity," "motivation," "judgment," "responsibility,"

and "technical ability." An overall rating is determined from

19/

Section B evaluation scores. Candidates are then interviewed

20/

by a promotion advisory board. The interview form requests

scoring on "appearance, bearing and manner," "ability in oral

expression," "stability and social adjustment," "mental qualities,"

"vitality," "maturity," "work attitudes," "motivation and

interest" and "subject matter knowledge." The Postmaster then

selects one of three names proposed by the advisory board.

2. Prima Facie Discrimination

Overall workforce statistics compiled by USPS Charlotte

for December 1, 1970 - May 31, 1971 constitute a prima facie

showing of systemic racial discrimination (A. 57-58, see also

56). Of 1436 employees of all grades, 72.8% (1045 of 1436)

were white and 27.2% (390 of 1436) black. Black employees are

disproportionately concentrated at low grade positions and

almost completely absent from high level positions. Thus, while

19/ The_appraisal form requests, in Section A, the following

information "describing the employee's performance and ability":

"attitude toward Postal Service," "knowledge of postal porcedures,"

"initiative," "ability to work effectively with others," "physical

vitality," "emotional stability," "leadership ability," "integrity,"

"ability and willingness to make decisions," "mental alertness" and

"personal conduct."

20/ Exhibit 7, attached hereto as Appendix B, infra at 5b .

- 18

9.6% (138 of 1436) of all employees were in grades 2-4, only

3.3% (34 of 1045) of white employees but 26.7% (104 of 390) of

21/

black employees held such low level jobs. While 82.7% (1187

of 1436) of all employees are in grades 5-7, white employees were

overrepresented (86.7% or 906 of 1045) and blacks underrepresented22/

(72.1% or 281 of 390). The pattern of white overrepresentation

and black underrepresentation at grades 5-7 is true of all higher

level as well. While 5.5% (79 of 1436) of all employees were

at grades 8-10, fully 7.0% (73 of 1045) of white employees and

23/

only 1.9% (6 of 309) of black employees held such jobs. All

24/

twenty 11-17 grade level positions were held by whites. By the

time Mr. Chisholm's administrative complaint was filed in March

1972, there was one high level black employee - at PMS-11, see

25/

supra at 15.

2-V Black employees were a majority at all these levels: grade

2, 80% (4 of 5); grade 3, 94.1% (16 of 17); and grade 4, 71.8%

(84 of 113). Black employees are a majority at no other levels.

22/ Black employees held 24.7% (244 of 986) of PMS-5 positions,

17.6% (33 of 187) of PMS-6 positions and 26.7% (4 of 15) of PMS-7

jobs.

23/ At level 8, 8.7% (4 of 46) were black; at level 9, 12.5% (2 of

16) were black; and at level 10, none of 17 were black.

24/ This included 9 level 11 positions, 4 level 12 positions, 3

level 13 positions, 2 level 14 positions, 1 level 15 positions and

I level 17 position.

25/ In fact, the disproportionality is greater when account is taken

of the fact that white women (9.7% or 101 of 1046 white employees)

are concentrated at lower level jobs and absent from all grades

higher than level 8. Excluding white women and comparing black

employees to white males alone would indicate greater statistical

disparity. The total of 1046 white employees also includes all

II ungraded rural carriers.

19

Available statistics on details to PMS-7 and higher

positions, supervisory training and promotions, reflect the

same pattern of statistical disparity (A. 67-70).

As to detailing, of 113 details to grades 7-14, fully

86.7% (98 of 113) details were assigned to white employees and

only 13.3% (15 of 113) to black employees in the December 1,

1970 - May 31, 1971 period. All 11 of the details to 11-14 level

positions went to white employees. Similarly, in the May 31,

1971 - November 30, 1971 period, fully 83.8% (93 of 111) of all

level 7-14 details went to white employees but only 15.3%

(17 of 111) to black employees. As in the earlier period, all

7 of the details to positions at grades 11-14 went to white

employees. With respect to employees chosen for supervisory

training, fully 91.2% (134 of 147) of all employees receiving

supervisory training were white but only 8.8% (13 of 147) black

from December 1, 1970 to May 31, 1971. For the next six month

period, 91% (172 of 189) were white but only 9% (17 of 189) black.

In the December 1, 1970 - May 31, 1971 period, there were

16 promotions: 6 of 10 promotions to white employees and all 6

of promotions to black employees were in grades 2-7,while all

4 high grade promotions were of white employees. In the succeeding

six month period, there were 32 promotions: 15 of 21 white

employees and 10 of 11 black employees were promoted to 2-7

level positions while 6 of the 7 promotions to higher positions

went to white employees. For the full 12 month period, 10 of

11 promotions to level 8-17 positions went to white employees.

From April 1, 1971 to March 31, 1972, 11 of 15 promotions to

level 8-9 positions went to white employees (R. 6, Admin. R. 69-72).

20

ARGUMENT

Introduction

It is clear that in actions brought by private company

and state or local government employees pursuant to § 706 of

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended, 42

U.S.C. § 2000e-5, it is unnecessary for all members of a class

to seek administrative resolution of their individual complaints

as a condition precedent to maintaining a Rule 23 class action; the

Supreme Court has so held twice within the last two terms. Albemarle

Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 414 n. 8 (1975); Franks v.

Bowman Transportation Co., ___ U.S. ___ , 47 L.Ed. 2.d 444, 465-

466 (1976). It also is now clear that, " [a] principal goal of

the amending legislation, the Equal Employment Opportunity Act

of 1972 . . . was to eradicate 'entrenched discrimination in

the Federal Service,* Morton v. Mancari, 417 U.S. 535, 547, by

. . . according 1 [a]ggrieved [federal] employees or applicants

. . . the full rights available in the private sector under

Title VII,'" Chandler v. Roudebush, ___ U.S. ___, 44 U.S.L.W.

4709, 4710 (Sup. Ct. June 1, 1976). Chandler dealt specifically

with whether federal employees suing under § 717 of Title VII,

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16, are entitled to the same Title VII right

to a plenary judicial proceeding or trial de_ novo under the

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure as private employees rather

than a-truncated review of the administrative record (as the

government contended). In upholding the right to a trial

21

de novo, a unanimous Court looked to the plain meaning of

statutory language and legislative history that "[t]he

provisions of section 2000e-5(f) through (k) of this title

shall govern civil actions brought hereunder," 42 u.S.C.

§ 2000e-16(d). It is those very sections of 2000e-5 which

the Supreme court and all other courts have construed to

allow a Rule 23 class action by a single employee who has

26/

exhausted his administrative remedies.

The principal question presented in this federal Title VII

action is not unprecedented in employment discrimination

jurisprudence; precisely the same kind of issue has been

litigated innumerable times in Title VII actions brought by

27/ 28/

private company employees and the United States. Plaintiff

Chisholm is attacking a range of employment policies and

practices that have the effect of discriminating against blacks

as a class "by stigmatization and explicit application of a

26/ The government has phrased its objection to class certifi

cation in terms of per se "jurisdiction" and "exhaustion". What

is at issue however, is much narrower: there is no doubt that

the district court had jurisdiction over the action or that Mr.

Chisholm has exhausted his administrative remedies. The only

question is whether the government’s additional and wholly technical

bar to a Rule 23 class action was properly rejected. For the

convenience of the Court, however, appellants will use the term

"exhaustion" in referring to the government's contention.

27/ See, e.g., Qatis v. Crown Zellerbach Corp., 398 F.2d 496

(5th Cir. 1968); Jenkins v. United Gas Corp., 400 F.2d 28 (5th

Cir. 1968); Bowe v. Colgate-Palmolive Co., 416 F.2d 711, 715 (7th

Cir. 1969).

28/ See, e.g.. Graniteville Co. v. EEOC. 438 F.2d 32 (4th Cir.

1971); United States v. Chesapeake and Ohio Ry. Co.. 471 F.2d

582 (4th Cir. 1972); United States v. Georgia Power Co., 474 F.2d

906 (5th Cir. 1973).

- 22

29/

badge of inferiority." Simply stated, federal employees

seek no more or less than what employees of a private company

31/

or state or local government employer are entitled under

Title VII. The federal government, on the other hand, seeks an

exemption from challenges to systemic discriminatory policies

and practices it itself has consistently encouraged in this and

other courts against all other alleged discriminatory employers.

The class action and intervention questions are but two

of the narrow technical devices which government lawyers

defending federal agencies in employment discrimination suits

have raised in a comprehensive and concerted effort to

forestall application to § 200e-16 actions, law developed

in private employee Title VII cases. Other such contentions

30/

29/ Sosna v. Iowa. 419 U.S. 393, 413 n. 1 (1975) (White, J.,

dissenting). Justice White, who dissented from the application

of established Title VII law to class actions generally, went

on to point out that congress in Title VII had given persons injured

by such systemic discrimination "standing . . . to continue an

attack upon such discrimination even though they fail to

establish injury to themselves in being denied employment

unlawfully." compare Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., supra,

47 L.Ed. 2d at 455-457; Moss v. Lane Co., 471 F.2d 853 (4th Cir.

1973); Barnett v. W. T. Grant, 518 F.2d 543 (4th Cir. 1975).

3°/ See, e.g., Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing Machine Co., 457

F.2d 1377 (4th Cir. 1972), cert, denied. 409 U.S. 982 (1972).

31/ See, e.g., Morrow v. Crisler, 479 F.2d 960 (5th Cir. 1973),

aff*d en banc, 491 F.2d 1053 (5th cir. 1974).

- 23

concern trial de novo, remand to agency proceedings in

33/

properly filed cases, federal court authority to grant Rule 65

34/ _ _ 15/

preliminary injunctive relief, notice of right to sue, and

36 /

application of Title VII substantive standards. Appellate

courts have rejected the government's basic contention that

Title VII principles developed in private sector cases do not

apply in each of these contexts and squarely held that, "The

intent of Congress in enacting the 1972 amendment to [Title VII]

extending its coverage to federal employment was to give those

public employees the same rights as private employees enjoy,"

Parks v. Dunlop, supra, 517 F.2d at 787. In rejecting the

government's contentions, the lower court also expressly

declared that federal employee Title VII actions should be

treated like any other Title VII case; e.g., "Congress intended

to give federal employees the same opportunity as private

employees enjoy to seek class relief in a civil action" (A. 36).

Thus, the district court's ruling permitting a class action and

intervention is wholly consistent with how other courts have

32/

32/ See, e.g., Chandler v. Roudebush, supra; Hackley v..Roudebush,

520 F.2d 108 (D.C. Cir. 1975).

33/ See, e.g., Grubbs v. Butz, 514 F.2d 1323 (D.C. Cir. 1975).

34/ see, e.g., Parks v. Dunlop, 517 F.2d 785 (5th cir. 1975).

35/ see, e.g., Coles v. Penny, 531 F.2d 609 (D.C. Cir. 1976).

36/ See, e.g., Day v. Weinberger, 530 F.2d 1083 (D.C. Cir. 1976)

(burden of proof); Douglas v. Hampton, 512 F.2d 976 (D.C. Cir.

1975) (remedies); see also Morton v. Mancari, 417 U.S. 535, 547

(1974) (substantive law generally). With respect to the retro

active effect of Title VII,. see Koger v. Ball, 497 F.2d 702 (4th

Cir. 1974); Place v. Weinberger, ___ U.S. ___, 44 U.S.L.W. 3718

(Sup. Ct. June 14, 1976), vacating, 497 F.2d 412 (6th Cir. 1974).

- 24

disposed of other narrow technical contentions raised by

3j/government lawyers defending employer agencies.

If the court below had accepted the government's contentions

on either trial de novo or class action, the result would have

been that no broad effective judicial inquiry of USPS Charlotte

employment policies and practices would have been permitted,

notwith standing the "plain . . . purpose of Congress to assure

equality of employment opportunities and to eliminate those

practices and devices which have fostered racially stratified

job environments to the disadvantage of minority citizens."

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792, 800 (1973),

38/

citing Griggs v. Duke Power Co.. 401 U.S. 424, 429 (1971).

" [C]ourts should ever be mindful that Congress, in enacting

37 / The common purpose of the government's objections to

the application of Title VII law is to nullify § 2000e-16,

enactment of which the spokesman for federal agencies, the

U„S. Civil Service Commission, unsuccessfully opposed in congress

as unnecessary. See chandler v. Roudebush. supra, 44 U.S.L.W. at

4712 n. 8; S. Rep. No. 92-415, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. 16 (1971),

reported in. Staff of Subcomm. On Labor of the Senate comm. On

Labor and Public Welfare, 92d Cong., 2d Sess. 425 (Comm. Print

1972) (hereinafter "Legislative History"); see also Hearings

Before the Subcomm. of the S. Comm, on Labor and Public Welfare,

92d Cong., 1st Sess. 296, 301, 318 (1971); Hearings Before the

Subcomm. on Labor of the H. Comm, on Education and Labor, 92d

Cong., 1st Sess. 386 (1971).

38/ See also Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 417

(1975); Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 47 L.Ed. 2d 444.

461 (1976T-------------------- ------------

- 25

Title VII, thought it necessary to provide a judicial

forum for the ultimate resolution of discriminatory

employment claims, it is the duty of the Courts to assure

the full availability of this forum." Alexander v. Gardner-

Denver Co., 415 U.S. 35, 60 n. 21 (1973); Chandler v. Roudebush,

supra. 44 U.S.L.W. at 4711. Title VII was amended to include

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16 in order "to make the courts the final

tribunal for the resolution of controversies over charges of

discrimination," Roger v. Ball, 497 F.2d 702, 706 (4th Cir. 1974),

for all employees. The result would be especially contrary to

the purpose of Title VII in this action in which the Court

below specifically found "a class action is not only proper in

this case but it is also superior to all other options available

to the Court" (A. 39).

Appellants' contention that every member of the class must

file an individual administrative complaint before a class action can

be brought boils down to precluding any meaningful use of

Rule 23, Fed. R. Civ. Pro., procedures in federal Title VII cases

no matter how appropriate such treatment would be under Rule

23(a) and (b)(2). The position of the government on class actions

is erroneous on several counts as decided by the lower court.

First, the language of § 2000e-16 in no way restricts the right

to maintain class actions as provided for by Rule 23. Second,

the legislative history of the 1972 amendments to Title VII

demonstrates congressional intent to allow broad class actions

26

and approval of prior judicial decisions to that effect.

Third, the administrative process does not permit class claims

to be accepted, investigated or resolved in an effective manner.

Fourth, the appellees1 secondary contention that the district

court abused its Rule 23(c) (1) discretion in broadly defining

the provisional scope of the class is also erroneous.

With respect to the district court's exercise of discretion

also to permit intervention by black employees who have not

previously sought administrative relief on their claims there

likewise was no abuse of discretion. Intervention pursuant to

Rule 24, Fed. R. Civ. Pro., is both proper and in accordance

with applicable principles developed in private employee Title

VII cases.

I.

A CLASS ACTION WAS PROPERLY CERTIFIED PUR

SUANT TO RULE 23(a) AND (b)(2), FED. R. CIV.

PRO.________________________________________

The lower court certified a class action and provisionally

defined a broad class after concluding that maintenance of a

class action was permissible on the basis of (a) statutory

language under which "courts enforcing Title VII have found the

class action vehicle as being particularly suitable to redress

claims of racial discrimination in employment"(A. 35), (b) specific

1972 legislative history (A. 36-37) and (c) the fact that "it [is]

difficult if not impossible for Chisholm to raise class issues

except in this forum" (A. 37). The government contends that

there is no jurisdiction for a class action and that the

27

conditionally defined class is too broad. Initially, however,

we note what the government does not contend. First, the

government no longer urges, as it did below, that, "'[wjhether

federal employees can maintain a Title VII class action is

best answered by deciding whether a Title VII action entitles

federal employees to a trial de novo after administrative

remedies have been unsuccessfully pursued. Clearly, if

court review of a federal employee's discrimination charge

were restricted to a review of the agency record a class

action would not be possible as it would require exploration

of factual issues obviously beyond the record of a single

employee.'" Defendants' Supplemental Memorandum at 3

(R. 29) citing Pendleton v. Schlesinger, 8 EPD ^[9598 at

5569 (D.D.C. 1974). Indeed, the government's brief does

not mention Chandler v. Roudebush, supra, in connection

with the class action issue, although Chandler leave no

doubt that federal employee Title VII actions are governed

by principles developed in private employee Title VII

cases. Indeed, decisions upholding the government's position

on the class action issue were decided before Chandler and

in reliance on an erroneous view of the trial de novo issue's

effect on exhaustion requirements, see Predmore v. Allen,

407 F. Supp. 1053, 1065-1066 (D. Md. 1975); none of these

39/

cases is now cited. On the other hand, the D. C. Circuit

39/ Hackley v. Roudebush, supra, 520 F.2d 152-153 n. 177.

28

and all the district courts which correctly decided the trial

de novo issue(because they concluded that Congress intended to

give federal employees the same rights and remedies as private

sector employees) also have, without,exception, permitted class

actions, resolving exhaustion contentions as the lower court did.

Thus, the government does not and cannot cite any reported court

authority that directly supports its exhaustion bar.

Second, the government does not contend that Mr. Chisholm

should have filed a separate "administrative class action" in

addition to his complaint as a condition to maintaining a Rule 23

class action. The government so argued in this court in Simmons

41/

v. Schlesinger, No. 75-2182, argued May 3, 1976, although

federal district courts have found that there is no way such an

42 /

administrative complaint could have been raised. The Justice

40/

40/ Williams v. Tennessee valley Authority. 415 F. Supp. 454

7M.D. Tenn. 1976); Barrett v. U. S. Civil Service Commission,

69 F.R.D. 544 (D.D.cI 1975); Keeler v. Hills, 408 F . Supp. 386

(N.D. Ga. 1975); Ellis v. Naval Air Rework Facility, 404 F. Supp.

391, (N.D. Cal. 1975); Predmore v. Allen, supra; Sylvester v. U. S .

Postal Service. 393 F. Supp. 1334 (S.D. Tex. 1975); Richerson v.

Fargo. 61 F.R.D. 641 (E.D. Penn. 1974).

41/ In its brief in Simmons v. Schlesinger at 31, the government

spoke to the contention that all members of a class must exhaust

individually in private Title VII cases as "effectively end[ing]

class actions in Title VII cases by limiting relief to those who

file a charge with the EEOC or were named in a charge. Such a

provision goes far beyond what [appellees] propound . . . "

42/ See, e.g.. Barrett v. U. S. Civil Service Commission, supra,

69 F.R.D. at 549-554; Williams v. Tennessee Valley Authority,

supra, 415 F. Supp at 458-459; Keeler v. Hills, supra, 408 F. Supp.

at 387-388; Ellis v. Naval Air Rework Facility, supra, 404 F. Supp.

at 394-395.

29

Department has so conceded and the Solicitor General

44/

so approved. In Barrett v. U. S. Civil Service Commission,

supra, 69 F.R.D. at 553, the district court specifically

granted a declaratory judgment because Title VII requires

modification of Civil Service Commission regulations to per

mit "consideration of class allegations in the context of

individual complaints." For the declaratory judgment and

order to this effect, see 10 EPD ^10,586 at 6450, see also

infra at Part I.C. of this brief.

43/

43/ See, e.g.. Brief For The Defendants-[Appellees],

McLaughlin v. Callaway, Fifth Circuit No. 75-2261, at p. 13

("As interpreted by the Civil Service Commission the regulations

do not permit filing of a class action administration com

plaint."), reversing position taken in, 382 F. Supp. 885

(S.D. Ala. 1974).

44/ Brief For Respondents, chandler v. Roudebush, No. 74-1599,

at p. 65 ("A district court I . has recently invalidated

Commission rules that effectively prohibited administrative

class actions. Barrett v. United States civil Service Com

mission. . . . "). 40/

40/ The Civil Service Commission has

now approved in concept the propriety

of administrative class actions and

we expect that draft regulations imple

menting Barrett will be published on

or before February 16, 1976.

30

The government does not raise the administrative

class action contention here, both because it is unsupport-

able and exposes facts that plainly undermine their present

contention. Thus, the government's elliptic reference

to Barrett at p. 24 n. 9 of their brief appears to suggest that

proposed revisions permitting separate administrative

class action procedures are somehow permissible under Barrett.

This of course is contrary to Barrett's holding on the

declaratory judgment which the government did not appeal and,

indeed, has elsewhere approved, supra. Some of appellant's

counsel, who are also plaintiff's counsel in Barrett, under

stand that the proposed revisions set forth at 41 F.R,

8079 have been withdrawn and are themselves being revised

for being contrary to Barrett. Moreover, footnote 9 concedes that

"the requirement of exhaustion will not necessarily require

that each individual exhaust separately" in light of Barrett,

although it is not clear the government understands what

Barrett really stands for. This concession calls into question

their present contention that all members of a class must

individually exhaust administrative remedies. No legal

doctrine justifies depriving these class members of the right

to maintain a class action because the government chooses

to urge an "exhaustion" bar bottom on illegal administrative

refusal of federal agencies to consider "class allegations

31

in the context of individual complaints." compare Love v .

Pullman Co. 404 U.S. 522 (1972).

Third, the government raises no issues with respect to

the propriety of the lower court's certification of the

class pursuant to Rule 23(a) and (b)(2), the specific finding

that "a class action is not only proper in this case but

it is also superior to all other options available to the

Court" (A. 39), nor the specific finding that it was

"difficult if not impossible for Chisholm to raise issues

except in this forum" (A. 37) aside from the question of the

scope of provisionally defined class. Thus the government

seeks to preclude a class action which, aside from scope of

the provisionally defined class, would be wholly appropriate

under safeguards of Rule 23(a) and (b)(2), and the best

and only way to resolve the claims of systemic discrimination

asserted.

As demonstrated above, the government has not hesitated

to change its horse midsteam or to advocate the most extreme

of positions in its effort to stifle congressional purpose and

remove Title VII as a practical means of curing systemic

federal employment discrimination. Clearly, what the govern

ment intends is to emasculate 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16 enforcement

suits as an effective weapon against class-wide discrimination.

Appellee suggests that the government's present position should

be considered in this light.

32

A. Class Actions Provided For In The Federal Rules Of

Civil Procedure Are Not Precluded By The Statutory

Language Of 42 U.S.C. 5 2000e-16

The right of federal employees to bring class actions

to enforce § 2000e-16 guarantees of equal employment opportunity

derives in the first instance from Rule 23, Fed. R. Civ. Pro.,

in accordance with 28 U.S.C. §§ 2072, 2073. Sibbach v. Wilson

& Co., 312 U.S. 1 (1941). The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure,

with certain exceptions not here relevant, extend to "all suits

of a civil nature whether cognizable as cases at law or in

equity or in admiralty." The federal courts thus have no

discretion to make ad_ hoc determinations whether specific civil

action statutes permit class action enforcement; class actions

are permitted unless statutory language expressly precludes or

limits class action treatment. Section 2000e-16, by its terms,

permits judicial consideration of class actions after one

named plaintiff exhausts his administrative remedies without

the additional preclusive exhaustion the government argues for.

As the lower court put it: "It is undisputed that Chisholm has

exhausted his administrative remedies, and, in his formal

administrative complaint, the plaintiff raised broad class-wide

issues of discrimination. It is well settled that a single

plaintiff who has met the procedural prerequisite under Title VII

may maintain a class action in court on behalf of all others

similarly situated" (A. 37).

There is no doubt after the Supreme court's landmark decision

in Chandler v. Roudebush, supra, that federal employee Title

VII actions, like § 2000e-5 suits, are "civil actions" fully

33

governed by the Federal Rules. "The Congress . . . chose to

give employees who had been through [administrative] procedures

the right to file a de novo 'civil action' equivalent to that

enjoyed by private sector employees," 44 U.S.L.W. 4716. The

necessity of § 2000e-5 trials de_ novo has been clear since

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., supra, and McDonnell Douglas v .

Green, 411 U.S. 792, 798-799 (1973), and the propriety of class

actions in Title VII enforcement suits since Griggs v. Duke Power

Co., supra, 401 U.S. at 429-30. Implicit, therefore, in the

general right to a trial de novo, is the specific right of a

plaintiff, in appropriate cases, to prosecute class actions pur

suant to Rule 23 in a fashion equivalent to § 2000e-5 class

actions. The government's proffered preclusive exhaustion rule

in derogation of this right is without basis or precedent in

Title VII jurisprudence and contrary to Chandler. It also, at the

very least, is wholly inappropriate in this action in which, as

noted above, the lower court has held that Rule 23(a) and (b)(2)

requirements are fully met, that the class action is "superior to

all other options" and that the class action is the only practi

cable means for considering the merits of the controversy.

1. Rule 23(b)(2) Fed.R. Civ. Pro.

Nothing in Rule 23(b)(2), under which the class action was

certified below, requires the government's exhaustion bar. The

inquiry required by Rule 23(b)(2) was described by the Advisory

Committee in the following broad terms: "Action or inaction is

directed to a class within the meaning of this subdivision even

34

if it has taken effect or is threatened only as to one or a

few members of the class, provided it is based on grounds which

have general application to the class." Proposed Amendments

to Rules of Civil Procedure, 39 F.R.D. 69, 102 (1966). The

technical exhaustion bar of every member of the class filing

an individual administrative complaint is thus contrary to the

preeminent purpose of Rule 23(b) (2) to provide practically for

full adjudication of claims against a defendant whose policies

or practices have general application to a class.

Moreover, Rule 23(b)(2) was specifically designed for

actions "in the civil rights field where a party is charged

with discriminating unlawfully against a class, usually one

whose members are incapable of specific enumeration. See

Advisory Committee's Notes, 39 F.R.D. 98, 102" (A. 39); Barnett

v. W. T. Grant, 518 F.2d 543, 547 (4th Cir. 1975); Johnson v .

Georgia Highway Express, Inc., 417 F.2d 1122, 1124 (5th cir.

1969). What plaintiff Chisholm in the instant case seeks

to raise and remedy in a court of law — systemic, class-"wide