Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School District Response to the Court's Letter Inquiries

Public Court Documents

May 11, 1977

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School District Response to the Court's Letter Inquiries, 1977. 44a4a305-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b7e9fe48-fa91-40be-9c2f-83398767b152/henry-v-clarksdale-municipal-separate-school-district-response-to-the-courts-letter-inquiries. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

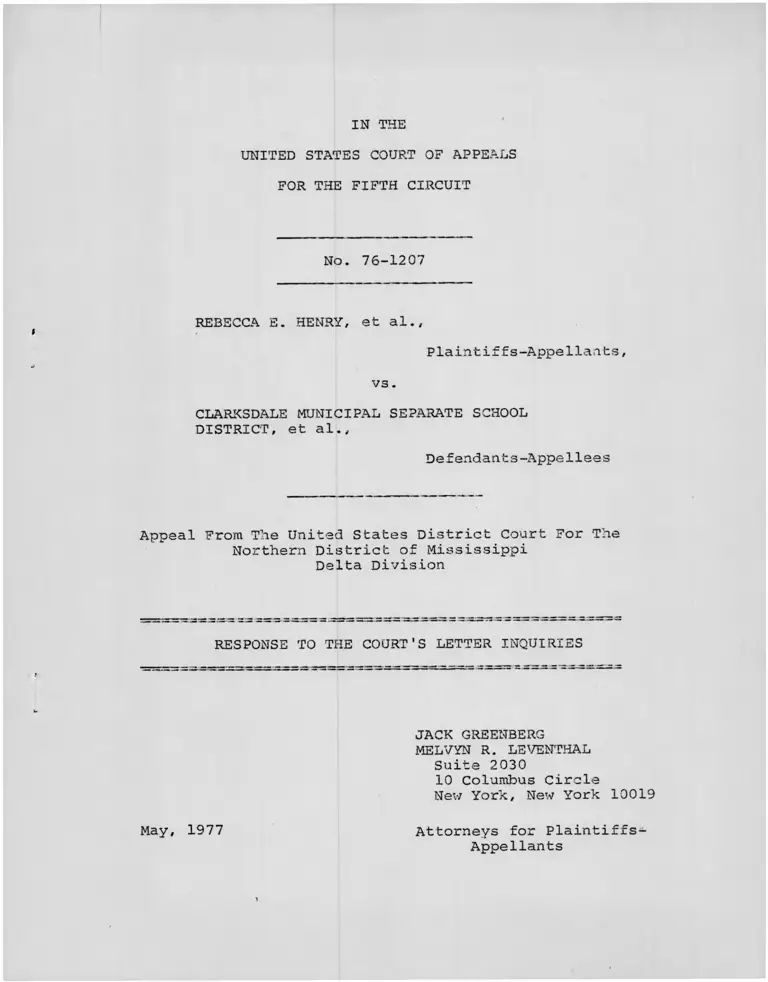

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

IN THE

No. 76-1207

REBECCA E. HENRY, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

vs.

CLARKSDALE MUNICIPAL SEPARATE SCHOOL

DISTRICT, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees

Appeal From The United States District Court For The

Northern District of Mississippi

Delta Division

RESPONSE TO THE COURT'S LETTER INQUIRIES

JACK GREENBERG

MELVYN R. LEVENTRAL

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

May, 1977 Attorneys for Plaintiffs-

Appellants

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 76-1207

REBECCA E. HENRY, et al.(

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

vs.

CLARKSDALE MUNICIPAL SEPARATE SCHOOL

DISTRICT, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees

Appeal From The United States District Court For The

Northern District of Mississippi

Delta Division

RESPONSE TO THE COURT'S LETTER INQUIRIES 1 2

1. Should Section 718 of the Emergency School Act,

20 U.S.C. 1617, be applied retroactively?

2. Is this case more closely analogous to Brewer v. School Board of Norfolk, 500 F.2d 1129 (4th Cir.

1974), or Scott v. Winston Salem/Forsyth City

Board of Education, 400 F.Supp. 65 (M.D.N.C.)

aff'd without opinion, 530 F.2d 969 (4th Cir.

1975?

3. Were Brewer and Scott correctly decided?

This case does not present an issue of retroactivity.

There was not, for example, a request for fees made prior

to the enactment of §1617, a denial of such fees, an

appeal and final disposition, followed by a request to

reopen and relitigate the fee issue after §1617 was

enacted. Retroactivity was the issue in Scott v. Winston-

Salem Forsyth County Board of Education, 400 F.Supp 65, 67

(M.D. N.C.), aff'd without opinion, 530 F.2d 969 (4th Cir.

1975). There plaintiffs had litigated and recovered

attorneys1 fees for time expended since the inception of

the litigation through June 11, 1973, the court and the

parties had considered the matter closed and plaintiffs,

nine months later, filed a second motion to recover fees

1/

from the inception of the litigation. Nor can there be

any real dispute that §1617 controls cases in which a

request for an award of fees (not a request for substantive

relief as was held by the district court) was pending on,

or timely entered subsequent to, the date §1617 was enacted.

That is the clear holding of Bradley, Brewer, supra, and a

1/ The issue of retroactivity arises when a final judg

ment with all appeals exhausted, is under collateral attack.

Thus in Linkletter v. Walker, 381 U.S. 618 (1965), the

exclusionary rule established by Mapp v. Ohio was applied

prespectively only, and was not available to state prisoner

whose judgment of conviction had become final prior to Mapp.

But the Mapp exclusionary rule applied to all cases pending

at the time of Mapp; Johnson v. New Jersey, 384 U.S. 719

(1966); See also O'Connor v. Ohio, 385 U.S. 92 (1956); Doughty v. Maxwell, 376 U.S. 202 (1964); United States v.

LaVallee, 330 F.2d 303 (2d Cir. 1964).

2

host of other cases. And both Brewer and Scott were

correctly decided.

The critical issue before the Court is whether in

a school desegregation case, a motion for an award of

fees must be entered early in the litigation or coin

cidentally with an order requiring the implementation

of what is perceived to be a final plan, or is a motion

for an award of fees timely when filed after the equit

able relief proves efficacious and the litigation nears

1/or reaches final resolution. Through the Clarksdale IV

2/

2/ Howard v. Allen, 368 F.Supp.310, 314-15 (S.C. 1973),

aff'd without opinion, 487 F.2d 1397 (4th Cir. 1973) cert.

denied, 417 U.S. 912(1974)(remedial or procedural statutes

to be applied "retrospectively," to cases pending at the time

of enactment). United States v. Hauqhton, 413 F.2d 736,738

(9th Cir. 1969)("Statutes effecting procedural changes, which

do not otherwise alter substantive rights, generally are con

sidered immediately applicable to pending cases.") Standard

Acc. Inc. Co. v. Miller, 170 F.2d 495 (7th Cir. 1948).

Seqars v. Gomez, 360 F.Supp. 50 (D.C. S.C. 1972). Bruner v.

United States, 343 U.S. 112 (1952); Ex parte Collett, 337

U.S. 55 (1949); Orr v. United States, 174 F.2d 577 (2d Cir.

1949); In re Moneys Deposited, etc. 243 F.2d 443 (3d Cir.

1957); Frye v. Celbrezze, 365 F.2d 865, 867 (4th Cir. 1966);

Bowles v. Strickland, 151 F.2d 419 (5th Cir. 1945); Hoadlev

v. San Francisco, 94 U.S. 4 (1876); Congress of Racial

Equality v. Clinton, 346 F.2d 911 (5th Cir. 1964); Rachel

v. Georgia, 342 F.2d 336 (5th Cir. 1965), aff'd 384 U.S.

780 (1966).

3/ That the litigation had not come to an end is further

"confirmed by a Motion of Defendants for Order of Dismissal

filed in the trial court on January 16, 1976. Therein

defendants acknowledge that the case did not come to a

conclusion until the school system had been operating,for

three years, a fully unitary system. See appellants

Motion for Leave to Supplement the Record [on appeal],

and order granting same, April 25, 1977, (per Tjoflat,

C.J) .

3

thislanguage quoted in the Court's letter inquiry,

Court has already resolved this critical issue in

plaintiffs' favor; i.e., the Court, in effect, held that

the litigation was drawing to a close with Clarksdale IV ^

and that a motion for fees was, at that point, appropriate.

Accordingly, Clarksdale IV indeed precludes the district

court holding that the litigation "had come to an end

before a request for fees had been made. 11 Moreover, the

Clarksdale IV holding is entirely responsive to consider

ations controlling school desegregation and equity litigation

generally.

In Johnson v. Combs, 471 F.2d 84, 87 (5th Cir. 1972)

1 /

4/ What effect does the following language in Clarksdale IV

have on the present litigation;

The district court shall also grant a

hearing to determine whether or not

the appellants’ actions in this lawsuit

were carried out in an "unreasonable

and obdurately obstinate" manner in the

years preceding July 1, 1972, so as to

entitle appellees to be awarded reason

able attorneys' fees for services before

that date. I_d. 585-86.

More specifically, is the finding of the district court

that this litigation had come to an end before a request for

fees had been made precluded by the above language?

5/ On remand the district court, on September 18, 1974,

entered an order requiring the submission of proof of

attorneys' fees in accordance with the mandate of Clarksdale

IV. (A.280-82) Plaintiffs, after obtaining extensions of^

time, filed their affidavits in Support of Motion for Award

of Fees on January 10, 1975 (A.281) and January 22, 1975

(A.287) .

4

(rejected on other grounds in Bradley v. Richmond School

Board, 416 U.S. 696, n. 20 (1974)), this Court held that

§1617 allows fee awards only "upon 'the entry of a final

order.' . . . Since most school cases involve relief of

an injunctive nature which must prove its efficacy over a

period of time it is obvious that many significant and

appealable decrees will occur in the course of litigation

which should not qualify as final in the sense of deter

mining the issues in controversy." See also, Appellants'

Reply Brief, pp. 7-11.

In Sprague v. Ticonic National Bank, 307 U.S. 161,

168 (1939) 83 L.Ed. 1184, plaintiff first requested attor-

neys' fees only after the conclusion of the case on the merits;

the trial court held that the request for fees came too late.

The Supreme Court reversed,holding through Mr. Justice

Frankfurter:

Certainly the claim for . . . [attorneys'

fees] was not directly in issue in the

original proceedings by Sprague . . . .

Its disposition . . . could be implied

only if a claim for such . . . [fees] was

necessarily implied in the claim in tne

original suit, and its failure to ask for

such . . . [fees] an implied waiver.

These implications are repelled by the

basis on which such costs are granted.

They are not of a routine character like

ordinary taxable costs; they are contingent

upon the exigencies of equitable litigation,

the final disposition of which in its entire

process including appeal place such a claim

in much better perspective than it would have

at an earlier stage. Such are the considerations which underlay the decision in Internal

Improv. Fund, v. Greenbough 105 U.S. 527,

5

in holding that an order allowing

. . . [attorneys fees] was a final

judgment for purposes of appeal

because 'the inguiry was a collateral

one, having a distinct and independent

character.

(Emphasis added)

Finally, the Court asks whether "plaintiff's request

for attorneys' fees, initially made in their brief on

appeal in Henry v. Clarksdale M.S.S.D., 480 F.2d 533 (5th

Cir. 1973) (Clarksdale IV), [was] sufficient to put fees

incurred prior to that time in issue," and whether "due

process considerations preclude such an application."

aWe have already argued that/motion for fees after

6/

remand of Clarksdale IV would have been timely; such

a motion was unnecessary since this Court, through its

mandate in Clarksdale IV, directed the district court to

consider an award of fees. In any event, under the

reasoning of Bradley there is no violation of due process

even assuming "a delay."

6/ Plaintiffs' 1954 Complaint prayed for "costs herein

and such further, other, additional or alternative relief

as may appear to the Court to be equitable and just."

(A.21-22) The Supreme Court has held that a challenge

to a private club's membership practices included, through

"a customary prayer for other relief" an attack on policies

for serving guests of members. Plaintiffs request for costs and

and other relief put defendants on notice that attorneys fees

could be sought. Irvis v. Moose Lodge, 407 U.S. 153, 170

(1972). Moreover, in light of Rule 54(c), FRCP, a court is

required to award all relief to which plaintiffs are entitled,

even when it is not specifically requested in a pleading, provided

there is no prejudice to the other party. Albemarle Paper Co.

v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 424 (1975). As to whether Clarksdale

defendants are prejudiced by an award of fees, see pp. 7-9

below.

6

The Bradley Court held that only upon proof of

"manifest injustice," could there by a departure from

the general rule that "a court is to apply the law in

effect at the time it renders its decision." The

Court undertook a three-part inquiry to determine under

what circumstances "manifest injustice" arises from the

application of the rule and, in the course of that

inquiry/fully explored all the "due process" arguments

available to a school district. Bradley, supra, 416

U.S. at 716-722. The Court began by noting that

"manifest injustice" will generally arise "in mere private

cases between individuals," or when as in Greene v. United

States, 376 U.S. 149, the government attempts to deprive

an individual of a matured and fully litigated claim

through the retroactive application of a new regulation,

416 U.S. at 717, and n. 24. In a school desegregation

case: (a) the "parties consist, on the one hand, of the

School Board, a publicly funded governmental entity, and,

on the other, a class of children whose constitutional

right to a nondiscriminatory education has been advanced

by . . . [the] litigation;" it is "not appropriate to

view the parties as engaged in a routine private lawsuit"

and plaintiffs are in fact representatives of the entire

community; (b) a "publicly elected school board" has no

"matured or unconditional right" to the "funds allocated

to it by the taxpayers," which funds "were essentially

held in trust for the public," (c) any claim that

7

"unanticipated obligations may be imposed upon . . .

[the school board] without notice or an opportunity

to be heard" has no cogency:

Here no increased burden was imposed

since §718 did not alter the Board's

constitutional responsibility for

providing pupils with a nondiscrimina-

tory education. Also there was no

change in the substantive obligation

of the parties. From the outset, upon

the filing of the original complaint in

1961, the Board engaged in a conscious

course of conduct with the knowledge

that, under different theories, . . .

the Board could have been required to

pay attorneys' fees. Even assuming a degree of uncertainty in the law at

that time regarding the Board1s con

stitutional obligations, there is no

indication that the obligation under

718, if known, rather than simply the

common-law availability of an award,

would have caused the Board to . . .

[alter] its conduct so as to render

this litigation unnecessary and there

by preclude the incurring of such costs.

The availability of 718 to sustain the

award of fees against the Board there

fore merely serves to create an addition

al basis or source for the Board's

potential obligation to pay attorney's

fees. It does not impose an additional

or unforeseen obligation upon it.

416 U.S. at 721.(Emphasis added.)

The three part inquiry undertaken in Bradley and in

particular its third aspect, quoted fully immediately

above, applies to the Clarksdale defendants. Assuming

that our prayer for costs in the original complaint (see

n.6, above), was not sufficient to put defendants on

notice that attorneys' fees may be sought (an assumption

8

rejected by Bradley), there is no indication that a

lack of such notice injured these defendants because

they hold funds in trust for the public and because

only the uninitiated would ask whether this school

board and this superintendent would have defended the

case differently if only they knew that they might be

held liable for plaintiffs' attorneys' fees.

Respectfully submitted,

JACK 'GREENBERG

MELVYN R. LEVENTHAL

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N.Y.10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-

Appellants.

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on this 11th day of May, 1977,

I caused to be served by United States mail, postage prepaid,

a copy of the foregoing Appellants Response to the Court's

Letter Inquiries upon counsel for appellees as follows:

Semmes Luckett, Esq.

121 Yazoo Avenue

Clarksdale, Mississippi 38614

Attoriley for Plaintiffs-

9