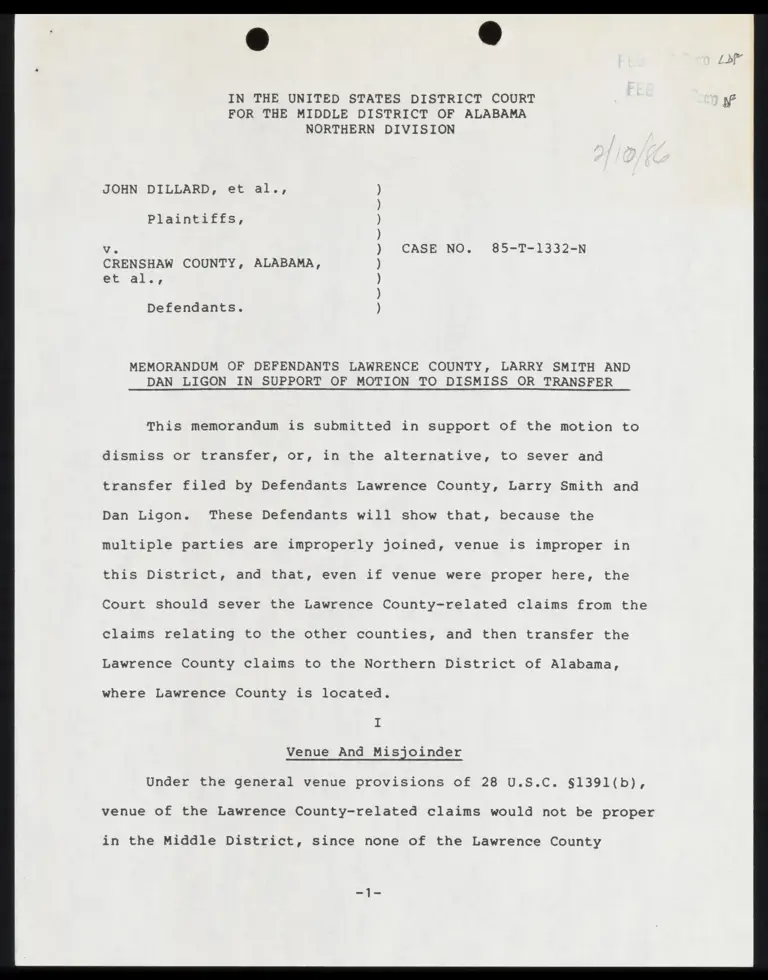

Memorandum of Defendants in Support of Motion to Dismiss or Transfer

Public Court Documents

February 10, 1986

25 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Dillard v. Crenshaw County Hardbacks. Memorandum of Defendants in Support of Motion to Dismiss or Transfer, 1986. cad856d3-b7d8-ef11-a730-7c1e527e6da9. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/bab1bdf5-7667-4f13-857d-98e325cfca21/memorandum-of-defendants-in-support-of-motion-to-dismiss-or-transfer. Accessed February 16, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT |

FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

NORTHERN DIVISION

JOHN DILLARD, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

Vv. CASE NO. 85-T-1332-N

CRENSHAW COUNTY, ALABAMA,

et al.,

N

a

N

t

”

a

w

t

u

e

l

w

t

?

S

a

s

”

w

t

’

q

u

i

t

Defendants.

MEMORANDUM OF DEFENDANTS LAWRENCE COUNTY, LARRY SMITH AND

DAN LIGON IN SUPPORT OF MOTION TO DISMISS OR TRANSFER

This memorandum is submitted in support of the motion to

dismiss or transfer, or, in the alternative, to sever and

transfer filed by Defendants Lawrence County, Larry Smith and

Dan Ligon. These Defendants will show that, because the

multiple parties are improperly joined, venue is improper in

this District, and that, even if venue were proper here, the

Court should sever the Lawrence County-related claims from the

claims relating to the other counties, and then transfer the

Lawrence County claims to the Northern District of Alabama,

where Lawrence County is located.

I

Venue And Misjoinder

Under the general venue provisions of 28 U.S.C. §1391(b),

venue of the Lawrence County-related claims would not be proper

in the Middle District, since none of the Lawrence County

Defendants reside in the Middle District, and the claims

certainly did not arise in the Middle District. However, the

Plaintiffs are expected to rely on 28 U.S.C. §1392(a) to

support their claim that venue is proper in the Middle

pistrict.t This section provides, essentially, that if

venue is good in one district of a state as to some defendant,

other defendants from other districts in the state may be sued

in the same suit, notwithstanding that venue would not

independently lie against the other defendants in the original

district. The rule is, as Wright & Miller have called it, "a

limited statutory escape" from the normal rule. Federal

Practice and Procedure, §3807, p.38 (1976).

The Plaintiffs' reliance on 28 U.S.C. §1392(b) frustrates

and undermines the purpose of the statute, and should not be

countenanced. Section 1392(b) was obviously enacted to cover

situations where a plaintiff (or a properly-joined group of

plaintiffs), having a claim against properly-joined multiple

defendants arising out of the same general transaction or

occurrence, would be thwarted in the effort to achieve relief

by having to pursue an otherwise-indivisible claim in several

forums, purely because of the strictures of the general venue

statute. See 1 Moore's Federal Practice 90.143.

yy The fact that this case is brought as a class action

does not make Sections 1391 and 1392(a) any less applicable.

Venue for a class action is determined just as it is in a

comparable type of nonclass action. 3B Moore's Federal

Practice $23.96.

The rule was not designed -- as it is sought to be used

here -- to give eight sets of plaintiffs the right to join

eight sets of defendants in one action where the respective

claims, relating to eight different counties, have little in

common factually, and where there is no basis under F.R.C.P.

20(a) for joinder of the multiple parties in the first place.

Inseparable from the §1392(b) venue question is whether

the multiple plaintiffs and multiple defendants are properly

joined in one action under F.R.C.P. 20(a). If they are,

§1392(b) arguably is a good basis for venue in the Middle

District. On the other hand, if the multiple parties are not

properly joined under Rule 20(a), §1392(b) is necessarily

inapplicable. See, e.g., Cheeseman v. Carey, 485 F.Supp. 203,

208-10 (S.D.N.Y. 1980).

Rule 20(a) provides, in pertinent part, as follows:

Permissive Joinder. All persons may

join in one action as plaintiffs if they

assert any right to relief jointly,

severally, or in the alternative in respect

of or arising out of the same transaction,

occurrence, or series of transactions or

occurrences and if any question of law or

fact common to all these persons will arise

in the action. All persons (and any

vessel, cargo or other property subject to

admiralty process in rem) may be joined in

one action as defendants if there is

asserted against them jointly, severally,

or in the alternative, any right to relief

in respect of or arising out of the same

transaction, occurrence, or series of

transactions or occurrences and 1f any

question of law or fact common to all

defendants will arise in the action.

« « « « (emphasis added)

in the present case, the requirements of Rule 20(a) are

not met because, as explained in more detail in the following

section, the claims made by the various county groups of

plaintiffs against the various county groups of defendants do

not arise out of the same transaction, occurrence, or series of

transactions or occurrences. The claims relating to Lawrence

County, for example, must necessarily be considered and decided

separately from the claims relating to Crenshaw County, because

the Court is required to make its decision on the vote dilution

question on the basis of a number of well-established factors

on which the evidence will necessarily differ from county to

county. See, United States v. Marengo County Cn., 731 F.2d

1546, 1566 (llth Cir. 1984), cert. denied, U.S. +103

S.Ct. 375, 83 L.EA.24 311 (1984).

Since the multiple parties are improperly joined in the

action, the very foundation for application of the §1392(b)

venue exception is completely eroded. If the exception is

designed to accommodate lawsuits which properly involve

multiple parties from more than one district, it follows that

there is no place for its application in a lawsuit where the

multiple parties are improperly joined in violation of Rule

20(a).

Under Rule 21 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure,

misjoinder of parties is not ground for dismissal of the

action. The Rule provides as follows:

Misjoinder of parties is not ground for

dismissal of an action. Parties may be

-—d-

dropped or added by order of the court on

motion of any party or of its own

initiative at any stage of the action and

on such terms as are just. Any claim

against a party may be severed and

proceeded with separately.

Similarly, 28 U.S.C. §1406(a) authorizes the dismissal or

transfer of cases from the district of improper venue to a

district where the claim could have been brought.

In the instant action, there is clearly a misjoinder of

the Lawrence County parties. Because of the misjoinder, the

venue exception of 28 U.S.C. §1392(b) does not apply to these

parties, and thus venue, as to them, is not good in the Middle

District. For all these reasons, and in accordance with the

provisions of Rule 21 and Section 1406(a), the Lawrence County

claims should be severed, transferred to the Northern District,

and proceeded with separately.

1}

Severance and Transfer

Even if the joinder of parties were appropriate, and even

if venue were technically proper in the Middle District, the

claims relating to Lawrence County should be severed from the

claims relating to the other counties, and then transferred to

the Northern District of Alabama for further proceedings.

Rule 20(b) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

authorizes the Court, in cases where there are multiple

parties, but where some of the parties have no claims against

each other, to order that separate trials be held, in order to

avoid embarrassment, delay or expense. Similarly, Rule 42(b)

authorizes the Court -- in furtherance of convenience, to avoid

prejudice, or when conducive to expedition and economy -- to

order a separate trial of any claim or issue which might be

included in a lawsuit with other claims and issues.

Section 1404(a) of Title 28 of the United States Code,

commonly referred to as the forum non conveniens statute,

authorizes the Court to transfer an action to any district

where it could originally have been brought, if such a transfer

would be "for the convenience of parties and witnesses" and "in

the interest of justice.”

As explained below, this Court should use Rules 20(b) and

42(b), and Section §1404(a), to sever the Lawrence County

claims from the claims against the other counties and then to

transfer the Lawrence County claims to the Northern District,

where they could have been brought originally.

It is well-settled law that Plaintiffs' claims under

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act must be considered and

decided by the Court before the Plaintiffs' claims based upon

the Constitution. Lee County Branch of NAACP v. City of

Opelika, 748 F.2d 1473, 1475 (llth Cir. 1984); Escambia County

V. McMillan, U.S. sy 104 8,Ct. 1577, 80 L.EA.24 36

(1984). For this reason, it is appropriate to consider the

present issue of severance and transfer principally in light of

Plaintiffs' statutory claims.

Brought under Section 2, the present claims against the

various counties are in reality eight separate "dilution"

cases, in which the Plaintiffs claim that their voting power

has been minimized by the existing election scheme in the

respective county of their residence. Of necessity, the merits

of these claims must be dealt with on a county-by-county basis,

because the evidence relating to the factors the Court is

required to consider obviously will be different from county to

county. See United States v. Marengo County Cn., supra, 731

F.2d at 1566; McMillan v. Escambia Cty., Fla., 748 F.2d 1037

(11th Cir. 1984); and Lee County Branch of NAACP v. City of

Opelika, supra. That is, the factors -- such as existence of

racially polarized voting, extent of participation by blacks in

the electoral process, election practices, and extent of

success of black candidates -- are geared to a particular

election system for a particular office or offices in a

particular locale, with a given electorate and a unique

election history.

The Court will readily see that, because of the lack of

typicality and commonality among the several counties, any

attempt at class action treatment will result in an

unmanageable conglomerate of factually-independent

mini-proceedings, with the absolute certainty that each such

proceeding will be decided in an independent evidentiary

hearing. At-large election systems for county commissions are

not inherently violative of either the Constitution or the

Voting Rights Act (United States v. Marengo County Cn., supra,

731 F.2d at 1564), and the existing at-large systems could,

theoretically, be adjudged lawful for elections in some

counties, while unlawful for elections in others, depending

entirely upon their differing circumstances -- circumstances

which can only be distinguished through full evidentiary

hearings. Obviously a finding in favor of the Plaintiffs with

respect to one county would not mean that persons in some

other, unique county have necessarily had their rights

violated.

Further, if liability were established, the remedy phase

for each county would necessarily have to be handled

separately. No particular remedy is required to redress a vote

dilution situation. United States v. Marengo County Cn.,

supra, 731 F.2d at 1566, note 24. If the Court allows this

action to proceed in its present form, at the remedy stage it

will simply be handling several independent cases under the

cumbersome and inefficient umbrella of one civil action.

Reluctant to belabor the point, we must emphasize that

joint consideration of the allegations made in the

multi-faceted, eight county complaint is impractical because

the validity of the allegations will depend upon which

particular county is being examined. The wide diversity of

factual circumstances which exists within the boundaries of the

-8w

State of Alabama is dramatically illustrated by two recent

decisions of the Eleventh Circuit Court, United States Vv.

Marengo County Cn., supra, and Lee County Branch of NAACP v.

Opelika, supra, both decided in 1984 under the amended version

of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act.

In Marengo County, the Court was considering whether the

at-large method of electing county commissioners resulted in

unlawful dilution of black voting strength under the "results"

test of the amended Section 2. The Eleventh Circuit set forth

the following list of factors to be considered in answering

this question (some factors having greater importance than

others):

Racially polarized voting;

Past discrimination and its lingering effect;

Access to the slating process;

Election practices (race of poll officials, etc.);

Enhancing factors;

Racial appeals in elections;

State policy;

Success of minority candidates;

Unresponsiveness of elected officials.

Applying these factors to the evidence relating to Marengo

County, the Eleventh Circuit concluded (at page 1574) that "the

record compels a finding that, as of the time of trial, Marengo

County's at-large system resulted in abridgement of black

citizens' opportunity to participate in the political process

and to elect representatives of their choice".

However, the Eleventh Circuit reached a completely

different answer 150 miles on the other side of the State in

City of Opelika, supra, holding that the plaintiffs had not

established that the at-large method of electing the city

government of Opelika constituted a violation of Section 2. In

explaining the different results, the Eleventh Circuit pointed

out important differences in the factual circumstances

relating to these two localities in the State of Alabama: The

court in Marengo had found extremely strong evidence of

polarized voting in elections in Marengo County, whereas in

Opelika, "evidence of racially polarized voting is weak".

There was evidence in Marengo that appointments of poll

officials were racially motivated, and tended toward tokenism,

and that the Board of Registrars limited the number of days

when it was open. In contrast, in Opelika the Registrar's

office is open every day of the week and the evidence shows the

use of black officials in voting and registration of voters.

Overall, the record in Opelika presented a much weaker showing

on the issues of racially polarized voting and election

practices than that in Marengo.

It is unlikely that the Court of Appeals would have

accepted the suggestion, if it had been offered, that these two

at-large voting systems should be tried together as a class

-0~

action because they both involved common questions of law and

fact under the Voting Rights Act, or that all of the at-large

forms of county government and city government in the State of

Alabama should be tried as a class action, simply because they

all involve questions of alleged voter dilution under the

Voting Rights Act. At-large voting systems are not inherently

unconstitutional, and they can be declared illegal only after

the relevant factors are applied to the particular election

district as required by the Eleventh Circuit.

Because the claims relating to Lawrence County must be

decided on evidence which, at least for most part, will relate

uniquely to Lawrence County, the Lawrence County claims should

be severed from the remainder of the action. Only the Lawrence

County Plaintiffs have standing to raise the claims relating to

Lawrence County, and only the Lawrence County Defendants have

the responsibility for defending those claims. The great bulk

of discovery on the Section 2 factors will necessarily involve

Lawrence County people and records, and not the people and

records of any other county. It makes sense to sever the

Lawrence County claims, and it makes no sense not to do so.

The severance should be accompanied by a transfer of the

Lawrence County claims to the Northern District pursuant to 28

U.S.C. §1404(a). Certainly the action could have been brought

in the Northern District, so it is a proper district to which

to transfer the case. It is also the best district for

resolution of the case, because it is unquestionably the most

We ©. YO

convenient and efficient forum for deciding this controversy.

All the interested parties reside in Lawrence County; most, if

not all, the witnesses who would be involved in the trial of

the Lawrence County aspect of this case reside in Lawrence

County; compulsory process for attendance of North Alabama

witnesses would be available in the Northern District, but is

questionable in the Middle District; and, generally, the

fact-intensive inquiry mandated by Marengo County and other

applicable Eleventh Circuit cases can more economically and

fairly be conducted in the Northern District, where Lawrence

County is located. Moreover, there is absolutely no nexus

between the Middle District of Alabama and the Lawrence County

aspect of this case.

The Plaintiffs may argue that each separate county claim

will involve evidence of the State of Alabama's race-related

history, and that this common feature of the claims warrants

their being litigated in one case. However, Marengo County

tells us that history -- that is, a history of racial

discrimination -- is only one of the several factors to be

considered in a dilution case, and that there is no prescribed

formula for aggregating the factors. 731 F.2d at 1574. The

ultimate conclusion, in each case, must be "based on the

totality of circumstances." 1d. Accordingly, it makes little

sense to decline an otherwise-appropriate severance and

transfer based on the possibility that the evidence on one

factor may be common to the various counties, when the evidence

WE §

on all the other factors will be different from county to

county. We would also note that, while evidence of past

discrimination was found to be "important" in Marengo County,

731 F.2d at 1567, the evidence discussed there principally

related not to state history, but rather to the history of

Marengo County: Hence, even the history factor of the

dilution equation has an important local component.

The wisdom of a Section 1404(a) transfer of the Lawrence

County aspect of this case to the Northern District is

illustrated by a famous decision from this very Court, issued

by a three-judge Court consisting of Judges Rives, Grooms, and

Johnson. In Lee v. Macon County Board of Education, et al.,

Civil Action No. 604-E, the suit brought by parents and school

children of Macon County to end racial segregation of the

County's public schools, the Court concluded that, because of a

wide range of activities carried out by the Governor and other

state officials designed to frustrate desegregation of the

State's public schools generally, only a statewide order

applicable to every school system in the State could

effectively achieve meaningful desegregation. The statewide

order was made applicable to every school system in the State

not then under court order, and was to be implemented through

the State Superintendent of Education. The individual school

boards were not made defendants.

2/ £/ +The Court did refer to "cases of statewide applica-

tion" as also being important in the Court's consideration of

the "history" factor. 731 F.2d at 1568.

-13-

In a series of later orders, the three-judge Court made

the State's individual school boards formal parties defendant

in Lee v. Macon, and maintained jurisdiction over the State's

school systems for some time.

when the individual school boards became parties, and as

it became clear that local issues, relating to particular

school systems, had begun to predominate over the statewide

issues, the Court, under the authority of 28 U.S.C. §1404(a),

severed the Lee v. Macon case, by school system, and

transferred it to the District Courts for the Northern, Middle

and Southern Districts of Alabama as it related to the county

and city school systems in those districts. A copy of the

Court's order is attached as an Appendix. It is particularly

important to note that, at page 5, the Court concluded that the

Lee v. Macon case had "evolved into many separate school

desegregation cases," and thus needed to be fragmented. The

Court also said:

It is quite evident that the convenience of

the parties and witnesses and the interest

of justice would be better served by the

decentralization of this case and the

transfer of the separate school

desegregation cases to the district courts

having regular jurisdiction over the areas

in which the school districts are

situated.

In the present case, as discussed above, the various local

issues (such as the existence of racially-polarized voting)

clearly predominate over the statewide issue (the State's

history of race discrimination). And it is absolutely clear

-l4-

that the considerations of convenience and economy weigh

heavily in favor of a §1404(a) transfer. Accordingly, this

Court should now transfer this part of the case to the Northern

District, just as the Lee v. Macon Court transferred the school

cases when they became, in effect, separate cases and local

issues came to predominate.

111

Class Action

The class certification question is not directly before

the Court, but it is probably inseparable from the issues

addressed above. For the same reason that joinder of the

Lawrence County parties and claims in this lawsuit is improper,

and for the same reasons that severance and transfer is

appropriate, this case is ill-suited for class action

treatment. If the Lawrence County claims were severed and

transferred, a plaintiff class of black citizens of Lawrence

County would arguably be appropriate. But a class of

plaintiffs from eight separate and distinct counties is not

appropriate. These Defendants respectfully reserve the right

to revisit this issue when it is formally before the Court.

Respectfully submitted,

D. L. Martin 77548

215 South Main Street

Moulton, AL 35650

(205) 974-9200

David R. tnd 7. 2.22

Attorney for Defendants

Lawrence County, Alabama,

Larry Smith and Dan Ligon

BALCH & BINGHAM

P. O. Box 78

Montgomery, Alabama 36101

(205) 834-6500

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that I have served the foregoing

Memorandum of Defendants Lawrence County, Larry Smith and Dan

Ligon in Support of Motion to Dismiss or Transfer, upon all

counsel of record listed below by placing copies of same in the

United States Mail, properly addressed and postage paid this

24 aay of January, 1986.

Aon HBr

V

OF COUNSEL

-16-

Larry T. Menefee, Esq.

James U. Blacksher, Esq.

wanda J. Cochran, Esq.

Blacksher, Menefee & Stein

405 Van Antwerp Building

P. O. Box 1051

Mobile, Alabama 36633

Terry G. Davis, Esq.

Seay & Davis

732 Carter Hill Road

P. O. Box 6125

Montgomery, Alabama 36106

Deborah Fins, Esq.

Julius L. Chambers, Esq.

NAACP Legal Defense Fund

1900 Hudson Street

l6th Floor

New York, New York 10013

Jack Floyd, Esq.

Floyd, Kenner & Cusimano

816 Chestnut Street

Gadsden, Alabama 35999

H. R. Burnham, Esq.

Burnham, Klinefelter, Halsey,

Jones & Cater

401 SouthTrust Bank Building

P. O. Box 1618

Anniston, Alabama 36202

Warren Rowe, Esq.

Rowe & Sawyer

P. O. Box 150

Enterprise, Alabama 36331

Reo Kirkland, Jr., Esq.

P. O. Box 646

Brewton, Alabama 36427

James W. Webb, Esq.

Webb, Crumpton, McGregor,

Schmaeling & Wilson

166 Commerce Street

P. O. BOX 238

Montgomery, Alabama

Lee Otts, Esq.

Otts & Moore

P. O. Box 467

36101

Brewton, Alabama 36427

W. O. Rirk, Jr., Esq.

Curry & Kirk

Phoenix Avenue

Carrollton, Alabama

Barry D. Vaughn, Esq.

Proctor & Vaughn

121 N. Norton Avenue

35447

Sylacauga, Alabama 35150

Alton Turner, Esq.

Turner & Jones

P. O Box 207

Luverne, Alabama 36049

DP. L. Martin, Esq.

215 S. Main Street

Moulton, Alabama 35650

Edward Still, Esq.

714 South 29th Street

Birmingham, Alabama

oe hy

35233-2810

4 - A PPENDI1LIX =

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE MIDDLE

DISTRICT OF ALABAMA, EASTERN DIVISION

FILED

MAR 3 1 1370

ANTHONY T. LEE, ET AL.,

Plaintiffs,

8. CIT ou

———— maaan

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

EE rT Pu

S&uy gine

Plaintiff-Intervenor

and Amicus Curiae,

NATIONAL EDUCATION CIVIL ACTION NO. 604~E

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

ASSOCIATION, INC., )

)

Plaintiff-Intervenor, )

K

)

)

)

)

)

)

vs.

MACON COUNTY BOARD OF

EDUCATION, ET AL.,

Defendants.

QRDER

This case was originally filed in January 1963, and

~

Ad

involved a petition for equitable relief by parents and school

children of Macon County against the Macon County Board of

Education, its superintendent and its individual members.

Jurisdiction was invoked under § 1343(3), Title 28, and § 1983,

Title 42, United States Code. The plaintiffs sought an injunction

prohibiting the Board from continuing to maintain its policy,

Practice and custom of compulsory biracial assignment of students

to the Macon County public schools. After a hearing, the relief

sought by the plaintiffs was granted by order entered on August 22,

1963. Lee v. Macon county Board of Education, 221 F.Supp. 297

(M.D.Ala. 1963). At this juncture the case represented no more

than a typical class action against a single school system. In

compliance with the court order, the Macon County Board of

>

go

Education assigned to its previously all-white Tuskegee High

School 1) Negro pupils who had exercised a choice to attend

that school.

On Ceptember 2, 1963, acting pursuant to an executive

order of tha Governor of Alabama, state troopers prevented these

13 Negro pupils from physically entering the Tuskegee High School.

The order, which was issued without the knowledge or consent of

the Macon County Board of Education, declared the school closed.

On September 9, 1963, state troopers acting on the Governor's

order again prevented the Negro students from entering the

school. A temporary restraining order was entered enjoining

implementation of the executive orders and enjoining any inter-

ference with compliance with the court orders. United States

v. Wallace, 222 F.Supp. 485 (M.D.Ala. 1963).

Subsequently, and in February 1964, the plaintiffs

filed an amended and supplemental complaint alleging that the

State Board of Education had asserted general control and super-

vision over all the public schools in the state in order to

continue the operation of a racially segregated school system

throughout the State of Alabama, and particularly in Macon Countv.

The State Board of Education and its members, the State Super-

intendent of Education and the Governor, as ex officio President

of the State Board of Education, wers made defendants. At the

same time, the plaintiffs sought to enjoin further enforcement

by defendants of Title 52, § 61 (13-21), Code of Alabama 1940,

and several other statutes that permitted the use of public

funds for the maintenance of "private' segregatad schools in

order to circumvent court orders. As a part of this supplemental

proceeding, the "tuition grant resolutions” of the State

Board of Education were challenged. At this point the District

T

r

p

e

r

? !

av -. - .

wlan er :

> . ? : . .

Judge requested, and the Chief Judga of tha United States Court

of Appeals constituted, a three-judge court pursuant to §§ 2281

and 2284, Title 28, United States Code. In July 1964, the

three-judge court sntered an order which enjoined, inter alia:

(1) Interference by the Governor, the Stata Board

or any member thereof with the desegregation of the Macon County

public schools; and

(2) The use of tuition grants for students enrolled

in schools discriminating on the basis of race or color:

Lee Vv. Macon County Board of Education, 231 F.Supp. 743 (M.D.

Ala. 1964) (three-judge court).

The three-judge court was called upon again to

consider whether the defendant state officials had continued

to use their authority to perpetuates a dual school systam based

upon race, and whether another tuition grant law, Title 52,

§ 61(8), Code of Alabama 1940, was constitutional. At this time

the plaintiffs sought a statewide desegregation order and an

injunction against the use of state funds to support a dual school

system. Thereafter, Governor George Wallace and Superintendent

Austin Meadows informed the school systems throughout the Stata

of Alabama that they should “take no action in the administration

and execution of compliance plans which are not required by law

or court order. . . ." Through “parables,” press releases to

local newspapers, and fund-shutoff threats, these state officials

exacted compliance from the local school boards, who promptly

discarded their plans to desegregate the public schools in most

of the counties throughout the State of Alabama.

Confronted with this situation in 1967, this Court

found that the state officials had engaged in a wide range of

activities designed to maintain segregated public cducation

throughout the State of Alabama, and that they in the past had

exercised and at that time continued to exercise the final

control and authority over all the public school systems in the

state. This Court concluded that only the imposition of a

statewide order, which at that time was made applicable to

every school system in the State of Alabama not then under court

order, would effectively achieve meaningful school desegregation.

"Freedom of choice" was adopted as the court-imposed statewide

plan. The court order was implemented through the State

Superintsndent of Education, and the individual school boards

and their members and superintendents were not made formal varties

defendant at that time. Lee v. g B atc]

267 F.Supp. 458 (M.D.Ala. 1967) (three-judge court).

The next episode in this case occurred in August 1968,

when this Court found it necessary to respond to motions for

additional relief filed by the United States and the original

plaintiffs. The motions presented at this juncture generally

sought a court order abandoning "freedom of choice" on the basis

of three Supreme Court cases decided May 27, thea Notwith-

standing the Supreme Court decisions, which this Court found

distinguishable on their facts, “freedom of choice" was reaffirmed

as “the most feasible method to pursue” for the several schosl

systems then involved in this case "at this time." In the

same order, faculty desegragation and minimum student standards

were ordered for each system. Lee v. Macon County Board of

Education, 292 F.Supp. 363 (M.D.Ala. 1968) (three-judge court).

Through subsequent orders, this three-judge court has amplifiad

and modified the August 1968 order, and through a series of

Ll/ Gxgen v. Countv School Board of New t County, 391 U.S. 430

(1968): Rainey v. Board of Education of the Gould School District,

391 U.S. 443 (1968), and Monroe v. Board of Commissioners of the

City of Jackson, 391 U.S. 450 (1968).

d=

.

uy Me.

— . -

- — —

—

gS | Ta BL

orders commencing on October 14, 1968, and continuing through

August 1969, has made the individual school boards, the members

thereof and the superinta:ndents formal parties defendant in

this proceeding. The case has, therefore, evolved into many

separate school desegregation cases concerning school systams

that are located in the three federal judicial districts of

Alabama. The school districts located within the geographical

limits of the Northern District of Alabama are listed, the

dates these systems and the members of the boards of thesa systems

were made parties defendant are set forth, and the current status

with regard to each of these systems is given on Exhibit A

attached to this order. The same information with regard to the

school systems located in the Southern District of Alabama is

given on Exhibit B which is attached to this order. This Court

has now concluded that after a "terminal-type"” plan for the

desegregation of a school system has been approved and ordered

implemented with the commencement of the 1970-71 school year,

the case, insofar as the school system wherein such plan has

been approved, should be transferred for supervision and for all

further proceedings to the United States District Court for the

geographic area in which the school system is situated.

Section 1404 (a), Title 28, United States Code, reads

as follows:

“For the convenience of the parties and

witnesses, in the interest of justice, a district

court may transfer any civil action to any

other district or division where it might

have been brought.”

It is quite evident that the convenience of the parties

and witnesses and the interest of justice would be better served

by the decentralization of this case and the transfer of the

separate school desegregation cases to the district courts having

§ % a. : v

regular jurisdiction over the areas in which the school districts

are situated. See Norwood Vv. Kirkpatrick, 349 U.S. 29 (1955);

1 Moore, Federal Practice. 1 0.145(5), p. 1786 (2d ed. 1967).

The fact that these cases have proceeded to this point prior to

transfer is immaterial. There is no question but that these

desegregation cases against the individual school systems could

have been brought in the United States District Court for the

geographic area whersin each such school system is located.

1 Moore, supra, § 0.145([6], pp. 1787-1800; 1 Barron and Holtzoff,

Federal Practice and Progeduge, § 86.2, pp. 283-287 (Wright ed.,

supplement 1967). See also Wright, Federal Courts, § 44, PP.

143-144. See also Vap Dusen v. Baryagk, 376 U.S. 612 (1964).

Thus, the original two-party action, concerning only

Macon County, that was commenced in this case in January 1963,

has evolved into an entirely different action, with the United

States as one of the plaintiffs, and the proceedings are now

directly against the various school boards located throughout

the State of Alabama. Therefore, both logically and legally,

these are individual cases which could have been brought in the

United States District Courts for the geographic arcas in which

the school districts are located. This Court will, therefore,

order transferred to the United States District Court for the

Northern District of Alabama the cases against the school boards

and individual members thereof, where terminal plans have been

approved to be implemented with the commencement of the 1970-71

school year, that are geographically situated in the Northern

District of Alabama. The Court will order transferred to the

United States District Court for the Southern District of Alabama

the cases involving the school boards and the individual members

. thereof, where terminal plans have been approved for implementation

_

effective with the commencement of the school year 1970-71,

that are geographically situated in the Southern District of

Alabama. As the other school systems are placed under terminal-

type orders by this three-judge court, they will also be

transferred to the district wherein they are situated.

Accordingly, it is the ORDER, JUDGMENT and DECREE of

this Court that the cases against the following school boards,

their superintendents and their individual members be and they

are hereby transferred pursuant to § 1404(a), Title 28, United

States Code, to the United States District Court for the

Northern District of Alabama:

county systems

Bibb

Blount

Cherokee

Clay

Cleburne

Colbert

Cullman

DeKalb

Etowah

Fayette

Franklin

City systems

Anniston

Athens

Attalla

Carbon Hill

Cullman

Decatur

Fort Payne

Guntersville

Jacksonville

Jasper

Mountain Brook

Greene

Jackson

Lamar

Lauderdale

Marion

Marshall

Morgan

St. Clair

Tuscaloosa

Walker

Winston

Muscle Shoals

Oneonta

Piedmont

Russellville

Scottsboro

Sheffield

Sylacauga

Tarrant City

Tuscaloosa

Tuscumbia

Winfield

It is further ORDERED that the cases against the

following school boards, their superintendents and their

individual members be and they are hereby transferred to the

United States District Court for the Southern District of

Alabama:

county systems

Baldwin

Clarke

Dallas

Washington

it g

Brewton

It is further ORDERED that the Clerk of this Court

forthwith physically transfer the court file of each of these

cases to the Clerk of the appropriate United States District

Court.

37

Done, this the 3/ "day of Lane 1970.

ELE Fi A:

UNITED STATES CIRCUIT JUDGE

KH Gs peer

UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE

UNITED — DISTRICT JUDGE =