McCord v. City of Fort Lauderdale, Florida Order and Opinion

Public Court Documents

March 12, 1985

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. McCord v. City of Fort Lauderdale, Florida Order and Opinion, 1985. 75706778-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/bb17913b-5618-458f-8706-4aefeb5efedc/mccord-v-city-of-fort-lauderdale-florida-order-and-opinion. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

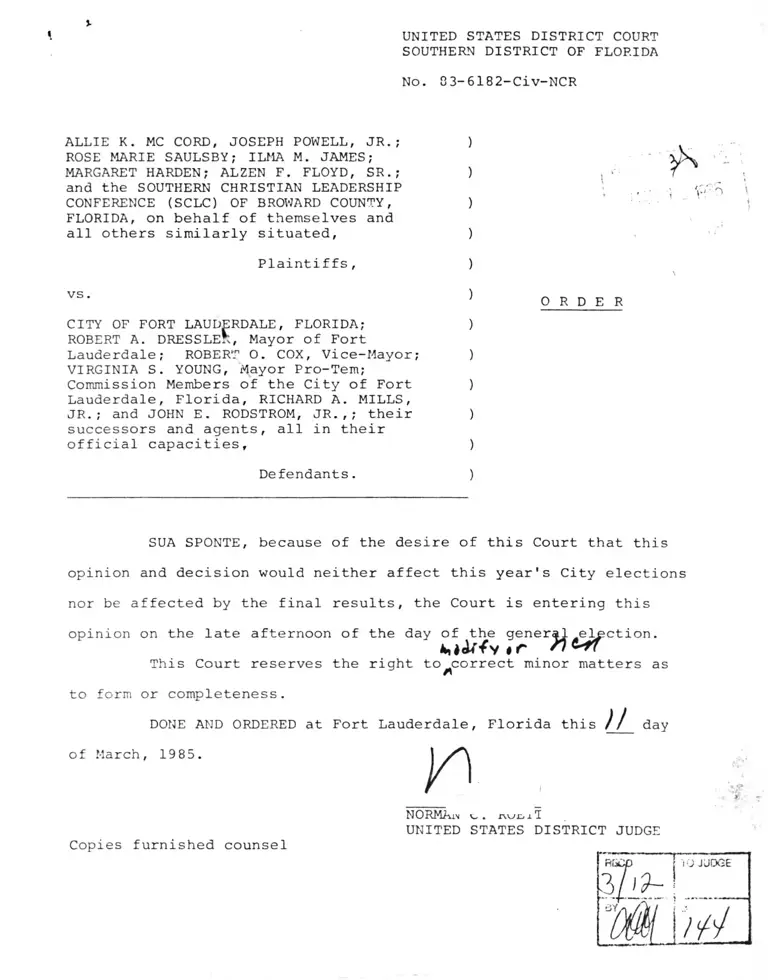

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF FLORIDA

No. 0 3-6182-Civ-NCR

ALLIE K. MC CORD, JOSEPH POWELL, JR.; )

ROSE MARIE SAULSBY; ILMA M. JAMES;

MARGARET HARDEN; ALZEN F. FLOYD, SR.; )

and the SOUTHERN CHRISTIAN LEADERSHIP

CONFERENCE (SCLC) OF BROWARD COUNTY, )

FLORIDA, on behalf of themselves and

all others similarly situated, )

Plaintiffs,

\

V S . O R D E R

CITY OF FORT LAUDERDALE, FLORIDA; )

ROBERT A. DRESSLEr, Mayor of Fort

Lauderdale; ROBERT O. COX, Vice-Mayor; )

VIRGINIA S. YOUNG, Mayor Pro-Tern;

Commission Members of the City of Fort )

Lauderdale, Florida, RICHARD A. MILLS,

JR.; and JOHN E. RODSTROM, JR.,; their )

successors and agents, all in their

official capacities, )

Defendants. )

SUA SPONTE, because of the desire of this Court that this

opinion and decision would neither affect this year's City elections

nor be affected by the final results, the Court is entering this

opinion on the late afternoon of the day of the general election.

This Court reserves the right to correct minor matters as

to form or completeness.

DONE AND ORDERED at Fort Lauderdale, Florida this ) f

of March, 1985.

day

n

NORMAN ROETTER, JR

UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE

Copies furnished counsel

V

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF FLORIDA

CASE NO. 83-6182-Civ-Roettger

ALLIE K. McCORD; JOSEPH

POWELL, JR.; ROSE MARIE SAULSBY;

ILMA M. JAMES; MARGARET HARDEN;

ALZEN F. FLOYD, SR.; and the

SOUTHERN CHRISTIAN LEADERSHIP

CONFERENCE (SCLC) OF BROWARD COUNTY,

FLORIDA, on behalf of themselves and

all others similarly situated,

Plaintiffs, O P I N I O N

vs .

CITY OF FORT LAUDERDALE, FLORIDA;

ROBERT A. DRESSLER, Mayor of Fort

Lauderdale; ROBERT 0. COX, Vice-Mayor;

VIRGINIA S. YOUNG, Mayor Pro-Tern;

Commission Members of the City of

Fort Lauderdale, Florida, RICHARD A.

MILLS, JR.; and JOHN E. RODSTROM, JR.;

their successors and agents, all in

their official capacities,

Defendants.

Plaintiffs sued the city of Fort Lauderdale, claiming

violation of the Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1973 in the

city's at-large elections for city commissioner.

It is important to bear in mind that an attempt to

discriminate or a discriminatory motive is not required under the

act following the 1982 amendment. Now, a sufficient violation is

shown—Lf— a discriminatory purpose or result may be inferred from

the voting practices.

The exact wording of the statute, as amended, is as

uws :

§ 1973. Denial or abridgement of right to vote on

account of race or color through voting qualifications

or prerequisites; establishment of violation

(a) No voting qualification or prerequisite to

voting or standard, practice, or procedure shall be

imposed or applied by any State or political

subdivision in a manner which results in a denial or

abridgement of the right of any citizen of the United

States to vote on account of race or color, or in

contravention of the guarantees set forth in section

1973b(f)(2) of this title, as provided in subsection

(b) of this section.

J k

V, W

V ill

it'*' p

(b) A violation of subsection (a) of this section

is established if, based on the totality of

circumstances, it is shown that the political processes

leading to nomination or election in the State or

political subdivision are not equally open to

participation by members of a class of citizens

protected by subsection (a) of this section in that its

members have less opportunity than other members of the

electorate to participate in the political process and

to elect representatives of their choice. The extent

to which members of a protected class have been elected

to office in the State or political subdivision is one

circumstance which may be considered: Provided, That

nothing in this section establishes a right to have

members of a protected class elected in numbers equal

to their proportion in the population. (As amended

Pub. L. 97-205, § 3, June 29, 1982, 96 Stat. 134.)

The trial evidence focused on the elections held since

70, primarily because the serious efforts in a black candidacy

began about that time. The candidacies prior to about 1970 on

the part of black candidates appeared obviously to be a "testing

1,, , CT L t /f !' ̂ . .d'j ̂VL& M

of the waters," while the candidacies beginning about 1970 have

been definite efforts on the part of all candidates, with perhaps

one exception.

Both sides treated 1970 as if it

starting date for our critical examination

prior to then were covered in the evidence

ovH1

b

a ! V

h &

were the important

although the matters

by both sides possibly

for historical completeness. E.g., plaintiffs' exhibit 1 (PX1)

gives exhaustive detail of the elections since 1970.

Since 1970 there has been an election in 1971, 1973,

1975, 1977, and in both 1979 and 1982 for three-year terms. All

of the commissioners have been white throughout this period,

except Fort Lauderdale elected a city commissioner, who was

black, in the at-large elections in 1973, 1975, and 1977. That

candidate was the same person, Andrew De Graffenreidt.

Key Facts for a Frame of Reference

There is no dispute between the parties as to the

following:

1. There have been four "open seats"— no incumbent

running— since 1970. The parties agree that open seats are the

key races to demonstrate electability.

2. Twenty-one percent of the city's present population

is black.

3. One open seat was won by Mr. De Graffenreidt, who

is black, in 1973, and he was re-elected in 1975 and 1977.

4. In 1975 and 1977 Mr. De Graffenreidt received

enough votes in identifiable white precincts to win election as

commissioner without any votes from black precincts.

5. Arthur Kennedy, also black, lost by a narrow margin

in the last election in 1982.

6. Black voter turnout has equaled (within one percentage

point) or exceeded white voter turnout (often substantially),

percentagewise, in every election since 1970 but one.

7. Since the city's founding in 1911, commissioners

(formerly council members) have been elected at large.

And, although not conceded by plaintiff, Fort

Lauderdale is not a part of the "Old South"; instead, most of its

white citizens come from the Northeast or Midwest.

These facts and others relevant to this decision will

be treated in more detail throughout this opinion.

Historical Background of City's Electoral System

The city of Fort Lauderdale was incorporated by the

Florida State Legislature in 1911. From 1911 to 1925, Fort

Lauderdale was governed by a Mayor-Council form of government;

and since 1925 the city has maintained a Mayor-Commission form of

government. Since 1911 there have been five members on the Fort

Lauderdale City Council or Commission (the term Commission has

been utilized since 1925).

From 1911 to 1917 the mayor served one year and the

council members for two years with staggered terms. In 1917 and

continuing to 1921, the mayor and the council served two

years, with the council serving staggered terms. Of the five

council members elected in 1922, the two candidates receiving the

highest number of votes served two years, and the two candidates

receiving the lowest number of votes served one year. In 1923

the mayor and council were elected for one year; two years with

concurrent terms in 1925; two years with staggered terms from

1929 to 1947. From 1947 to 1951, commissioners were elected for

four-year staggered terms, and from 1951 to 1979 they served

f

two-year concurrent terms. Since 1979, the mayor and

commissioners have served three-year concurrent terms.

Election of Council Members and Commissioners

by Ward, Districts, or At-Large

Since 1911 council members or commissioners have been

elected at-large. From 1913 to 1923, four of five commission

members were elected at-large, but they ran from districts in

which they resided. One of five ran at-large, but not from any

district. The residency requirement was deleted from 1923 to

1929. From 1929 to 1947, the four and one split was again

instituted, but from 1947 to the present, the system has been

that all commissioners are elected at-large, but with no

residency requirements.1/ In the 1979 election, only four

commissioners were elected at-large with the fifth running

separately as mayor, also at-large, but in 1982 the separate

mayoralty race was abolished with all five commissioners being

elected at large, as usual. City commissioners are elected by

plurality vote in both the primary and general elections. In the

primary election, the 10 candidates who receive the highest

number of votes become candidates in the general election; and in

the general election, the five candidates who receive the highest

number of votes become city commissioners.

\

/

1/However, plaintiffs in this case rejected this solution of

a residence district requirement from five districts in the city

with at-large voting for the elections of persons from the

various districts, despite the fact this would almost guarantee

the election of a black commissioner. This proposal was made by

the court in an effort to resolve the situation without extensive litigation.

3

fyt-r

(

V /

<5 CilCfi

(A' O-'1

( S 0 or e

-/ U f c r - f ' } T t S a

Since 1913 the candidates elected to office were those

receiving a plurality of votes. The one receiving the highest

number of votes was declared to be the mayor-commissioner, and

the one receiving the second highest was declared to be

vice-mayor-commissioner.

There is no white or segregated primary in the city of

Fort Lauderdale. There is no prohibition against single-shot

voting. There is no requirement for majority vote and there

never has been except from 1923 to 1925. During that period, the

----------majority vote requirement was used when there were only two

candidates. In those elections during this period, where there

were more than two candidates for a position, only a plurality of

votes was required to be elected. Therefore, as a practical

matter, there never has been a requirement for a majority vote,

even during those two years.

Population and Demographic Statistics for the City

The population of Fort Lauderdale in the 1980 census

was a total of 153,279, of whom 32,225 (21%) were black. Fifty

years earlier, the 1930 census showed a total population of

8,666, of whom 1,994 (23%) were black.

The city produced expert testimony2/ that Fort

Lauderdale has only 23% native Floridians, a much lower figure

than for several other cities in Florida. An examination of the

demographic patterns of immigration from 1975 to 1980 indicates

that 45% of Fort Lauderdale's residents came from the

____________________/

2/Professor Susan A. MacManus, Cleveland State University, Cleveland, Ohio.

northeastern part of the United States, 18% from the Midwest, and

only 17% from other southern communities. This demographic

pattern is similar to prior demographic patterns.

The evidence reveals that Fort Lauderdale is a part of

"New Florida" with a more tolerant and unbiased racial attitude

while some other comparative communities in Central and North

Florida reflect "Old Florida," which itself is like the "Old

South."

Black Candidates for the Fort Lauderdale City Commission

The black candidates prior to about 1970 appeared to be

largely a testing of the political waters and began with

Nathanial Wilkerson in 1957; almost no evidence was introduced as

to his campaign. In 1963, Thomas Reddick, a lawyer, ran for city

commission, and in 1967 a full slate of five candidates, all of

whom were black, ran for city commission: Horace Lewis, Helen

Morris, Edison Wheeler, Tom Reddick, and Walter Sullivan. The

announced purpose of the campaign, according to Commissioner De

Graffenreidt, was to see if black voters would go to the polls.

In 1969 and 1971, Alcee Hastings, a lawyer and presently a United

States District Judge, ran, but finished seventh.

In 1973, Andrew De Graffenreidt ran for the city

commission and was elected; Commissioner De Graffenreidt was

re-elected in both 1975 and 1977. In 1979, Commissioner De

Graffenreidt ran for re-election as a city commissioner and was

narrowly defeated, for reasons to be discussed at more length

later. In 1982, two black candidates ran: Arthur Kennedy,

President of the Broward Classroom Teacher's Association,

*7

•** -J***,

narrowly lost, and a young college student, Louis Alston, ran

with a rather unsubstantial showing.

The comments of the candidates about their own races

are instructive as to their respective defeats. Tom Reddick, who

ran in 1963 and 1967, analyzed that Republicans were getting

elected in his campaigns and he was a Democrat. Horace Lewis,

who ran in 1967, spent less than $100 and took out no ads. Helen

Morris, who also ran in 1967, took out only one ad and limited

her campaigning to one street. Neither Morris nor Lewis had been

active in city affairs before then, although Morris has since

been appointed to serve on an advisory board.

Alcee Hastings, a candidate in 1969 and 1971,

attributes his election difficulties to many things: Someone

gave him 5,000 bumper stickers but because they did not have the

union "bug" on them, the unions were mad at him. He attributes

his drop from fifth or sixth in 1969 to seventh in the general

election to the fact that more people knew he was black; he

further felt that black Democrats support white Democrats but not

vice versa.

In 1973, 1975, and 1977, Andrew De Graffenreidt was

elected, but then after two races for other positions lost in

1979. (His successor, Bert Frazer, ran but was defeated in

1982.) The matter that seemed largest to Commissioner De

Graffenreidt for his defeat was "because I resigned to run [for

the county commission in 1978] and was reappointed [by his fellow

members on the Fort Lauderdale City Commission], the press was

unsupportive." The Fort Lauderdale News did not endorse him in

1979 because of that, although he had enjoyed the endorsement of

The Fort Lauderdale News in previous campaigns. The State of

Florida requires that one must resign to run for a state office.

Consequently, in 1976 when Commissioner De Graffenreidt ran for

Congress, he did not resign, but when he ran for the county

commission in 1978, he had to resign his city of Fort Lauderdale

City Commission post. The other city commissioners— all

white— deliberately kept the position vacant until they saw what

the results of the county commission race would be. When

Commissioner De Graffenreidt lost, he was reappointed by his

fellow members of the city commission to his old seat.

Additionally, Commissioner De Graffenreidt felt the

voters were unhappy because he had opposed buying the Bartlett

Estate (the last large available undeveloped tract on Fort

Lauderdale Beach), and he blames that for a drop in his vote

totals. Not only did he oppose it, but Commissioners Young and

Mills also opposed it and their vote totals dropped, too;

however, the city's overall vote totals dropped 3,546 votes from

the 1977 election to the 1979 election, with the totals for Mayor

Shaw— running specifically for mayor this time— dropping by 2,134

votes. Commissioners De Graffenreidt, Young, and Mills dropped

their vote totals by 2,165, 1,960, and 1,474, respectively, but

Commissioner Cox dropped only 195 votes. Commissioner

De Graffenreidt testified he "lost luster" in the black community

and the voter turnout ebbed (confirmed by election statistics).

Arthur Kennedy, who narrowly lost by about 3% of the

total votes cast in 1982, felt that a big turnout was important

. . V . ■satf. ■ * 4 I ' . . .

for him because the more people who voted, the better off he

would be as a candidate. However, the turnout was low at

election. Clearly, the matter that bothered Mr. Kennedy the most

was the fact that three power brokers (as he describes them) whom

he avoided and also did not solicit money from, were unhappy with

him, and he feels two of them were behind a letter mailed out on

the Saturday before the election. His staff advised him not to

respond to it, but he wishes he had done so.

The court asked to see the letter and it was received

as a court exhibit. The letter is on the letterhead of the

Broward County Republican Party, reminding the voters of Fort

Lauderdale that the property taxes in the county had doubled

since the Broward County Commission was "taken over by Democrats"

four years earlier. The letter went on to point out that the

conservative Republican majority on the Fort Lauderdale City

Commission had controlled spending and kept the city taxes in

line. Then the letter specifically sounds the bugle for the

Republican party faithful, pointing out that a majority of the

top five finishers in the primary were Democrats, one a

27-year-old candidate running for the first time, and Arthur

Kennedy^ descrjjaed as— 'La. labor_leader that has a direct interest

in 'not rocking the boat, but sinking it,1_if_ he gets elected."

The letter then urged that Republican party members— presumably

the only addressees of the letter— elect a conservative majority

to the city commission and recommended four candidates:

incumbents Bob Cox, Richard Mills, and newcomer candidates Rob

Dressier and John Rodstrom. The fact that Art Kennedy was a

1 A

* mu:*

former member of the Democratic Executive Committee was a matter

undoubtedly not lost on the persons behind this election eve

letter.

The letter was successful: The four persons

recommended were all elected in the 1982 general election. The

city also elicited from Mr. Kennedy that he used up half or more

than half of his campaign funds in the primary campaign rather

than holding them for the general election, despite the existence

of only 11 candidates and the primary would only reduce the field

to 10 candidates.

Arthur Kennedy candidly observed that nearly all the

commissioners in the last two decades have been Republicans--al1

except for Mayor Young and Commissioner De Graffenreidt. He also

acknowledged that Mayor Young is regarded in the white community

as basically conservative, but that her support among "voters in

the Northwest area...[is] almost a given."

Neither lawyer had seen the letter referred to by Mr.

Kennedy (court exhibit 1), and there was no other evidence of

partisan activity in past city elections. The evidence does show

the exclusive preference of the Broward Citizens Committee for

Republican candidates.

The Nine Factors

The first factor indicated in the Senate report an^

U.S. v. Dallas County Commission, 739 F.2d 1529, 1534 (11th Cir.

1984), is the extent of any history of official discrimination

"that touched the right of minority groups to... participate in

the democratic process." Turning to it at this time, this court

permitted introduction of evidence of discrimination during the

post-Civil War period in enactments by the State of Florida and

during the reconstruction throughout the remainder of the 19th

century and early 20th century. The relevance of this evidence

to the city of Fort Lauderdale is dubious because of the fact

that Fort Lauderdale was not even a trading post at the time of

Reconstruction; the court can take judicial notice of the

historical fact that Frank Stranahan1s trading post on the New

River was the nucleus around which Fort Lauderdale began, and a

village began to take shape at the turn of the century, assisted

greatly by the construction of Henry Flagler's railroad, which

finally pushed down the Atlantic coast to Miami in 1896. As

noted earlier, Fort Lauderdale did not become a city until 1911.

Whatever may have been the situation in the state of Florida in

the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, there

have been almost none of the usual badges of bias against

minorities participating in the political process: There has

been no white or segregated primary in the city; there has been

no prohibition against single-shot voting, and no_■•py1' for

a majority vote. A poll tax was required to be paid for two

years from 1911 to 1917; from 1917 to 1919 no poll tax was

required. In 1919, women's suffrage was obtained and poll taxes

were reinstated, but since 1929 there have been no poll taxes

required. The elections are officially nonpartisan.

However, there was evidence of discrimination against

blacks in the city of Fort Lauderdale in the past.

In 1922 an ordinance was enacted which created a legal

color line" segregating blacks into the northwest area of the

city, west of the railroad tracks. A violation of this ordinance

carried a penalty of both a fine and imprisonment. The ordinance

remained basically in effect for 25 years.

In 1926 an ordinance was created which provided for the

creation of a "Negro district" and "no residence or apartment

house could be used to house Negro families with the exception of

servants' quarters." Action was taken in 1929 to enforce the

ordinance. In 1936 the boundary of the "Negro district" was

redefined, and in 1939 the planning and zoning commission

recommended an increase in the size of the "Negro district." A

few months later, the ordinance was repealed with an ordinance

restoring the "Negro district" to its earlier boundaries in 1942.

The advisory board recommended the acquisition of land

for a buffer area around the "Negro district," and during the war

Dillard School, the black high school, would be closed

periodically so black children could work in the vegetable fields.

That was challenged (unsuccessfully) in 1945 in federal court.

See Walker Civil League v. School Board, 154 F.2d 726 (5th Cir.

1946 ) .

The segregation ordinance about the "Negro district"

was repealed in 1948.3/

Plaintiffs claim that Fort Lauderdale's abandonment of

a district residency requirement in 1947 simply was a lock step

or shadow effect to emulate the State of Florida in getting

around Smith v. Allriqht, 321 U.S. 649 (1944), and the striking

down of the white primary in Davis v. State ex rel. Cromwell, 156

Fla. 181, 23 So.2d 85 (1945). However, the court cannot agree

with plaintiffs' assertions because the simple fact of the matter

is that Fort Lauderdale has had at-large elections of its city

commissioners from the very beginning in 1911. Additionally,

there has been no white primary, as such. There have been some

requirements from time to time in the city's history that

commissioners reside in certain districts but they still ran

at-large.

There is no reason to conclude from the evidence in

this case that the official discrimination, either in the State

of Florida or in Fort Lauderdale, has adversely affected the

right of the members of the plaintiff minority group either to

register or to vote or otherwise to participate in the democratic

____________________/

3/Tnere are other examples set forth in the evidence of

discrimination, some tenuous to the point of being erroneous,

such as newspaper clippings as to the Ku Klux Klan rallies in

Central Florida. However, there have been some instances of

discrimination in Fort Lauderdale; for example, the petition by

some black residents to use the municipally-owned golf course

during the 1950's. A city resolution (6247) expressed fear of

adverse tourist reaction if the petition was granted. The United

States Disrict Court ordered integration of the golf course and

the city sold the golf course. There were also various petitions

to hire black police officers to patrol in the black residential areas.

process. This is particularly true when we consider that,

generally speaking, black voters since 1970 have voted,

percentagewise, as much as or more than white voters in every

election but one.

Moving on to the second matter pesented by the Senate

report, the extent to which voting in Fort Lauderdale is racially

polarized, we find a battle of expert witnesses with widely

divergent conclusions. Plaintiff presented Dr. de la Garza, a

professor at the University of Texas, while defendant relied on

Dr. Bullock, a professor at the University of Georgia.

Dr. de la Garza relies on a bivariate statistical

analysis; that is, he checks only the issue of race in

determining what factors affected the votes cast for a candidate,

whereas Bullock checked the voting patterns from a number of

independent variables, including, but not limited to, incumbency

of the candidate, campaign funds spent, whether male or female,

whether newspaper endorsements were received, voter turnout

either in the black or white community, the proportion of the

registered voters who were black, jand party— "in some instances"

(although the court does not believe this was fully explored or

utilized.)

Although there has been some judicial consideration of

bivariate vis-a-vis multi-variate analysis (and that will be

discussed later in this order), the court wanted to compare the

analyses when tested against some actual events and realities in

order to determine which theory seemed to be more sound and of

more assistance to the court in determining whether the at-large

.15

election system in Fort Lauderdale impacted illegally on the

rights of the black citizens of the city.

Dr. de la Garza's analysis was fairly simple in that

he counted every vote cast by a voter and then used raw scores of

the number of votes for black candidates vis-a-vis the number of

blacks registered in the precincts, coming up with a regression

figure ranging from .81 to .99, with 13 of 18 elections over .90

(De La Garza calculated all elections with a black candidate with

the apparent exception of the 1963 primary and the 1979

elect ions).

His second regression reflects the percentage of votes

received by a black candidate as a function of turnout ratio

(number of votes cast by a precinct as a function of a number of

votes they could have cast). Tr. 256. The regressions ranged

from .51 to .99. When the two analyses are combined, the R2

ranges from .82 to .99, with most over .91.

Dr. de la Garza counts vote totals rather than voters

(at least he does so with the white precincts), and therein lies

(the statistical problem when methodology more suited for

head-to-head elections is applied to this particular at-large

system.

By comparison, Dr. Bullock examined the 12 elections

since 1970: a primary and a general in 1971, 1973, 1975, 1977,

1979 (only four commissioners elected), and 1982. There was at

least one black candidate in each of these elections, and these

are the elections the parties have focused on. (He apparently

also compared the 1969 elections.) Dr. Bullock considered

several independent variables: newspaper endorsements, campaign

spending, incumbency, level of turnout in the black or white

community, gender, as well as race, among others. He noted

that in three of the 14 elections, a black candidate received 40%

or more of the support of the white voters. Note: There has

been at least one black candidate in each of the 14 elections.

In seven other elections, a black candidate received between 30%

and 39.9% support of the white voters.

Dr. Bullock also examined 15 other elections in which

Fort Lauderdale citizens could vote which had black candidates

competing against white candidates. In those 15, a majority of

Fort Lauderdale citizens preferred black candidates in four

elections: the Florida Supreme Court election in 1976 (then

Justice Hatchett, now Judge Hatchett of the U.S. Court of Appeals

for the Eleventh Circuit), Alcee Hastings in the 1974 Public

Service Commission primary, City Commissioner De Graffenreidt

running for the Broward County Commission, plus another race. In

addition, in other elections, four of the black candidates

received 40% to 49.9% of the ^hite voteT]

In only two of the 14 Fort Lauderdale elections has a

black candidate (Alston, in both instances) received less than

20% of the'^white vote?, only those two races would indicate racial

polarization under the Loewen standard (80%-20% polarization

benchmark). Alston also ran less strongly in black precincts

than had other black candidates.

_______________________/

4/Dr. de la Garza agrees these factors, and more, do affect

elections. ic-c-ẑ q -CU*j -vtoj ^py o lo^ue r

^ ̂ Q0^07 - r L

(evil —

17

'..•k /a-

J r '

, *

Dr. Bullock also concluded that whites more generally

Q\ X

0 vote for blacks than black voters for white candidates. Dr.

Bullock's conclusion was that the variable of race is not one of

the important variables. His conclusions were that the important

variables are like this: The candidate is more likely to win a

seat on the Fort Lauderdale City Commission if:

1. The candidate is an incumbent.

2. The candidate spends more.

3. The candidate receives newspaper endorsements.

4. White voter turnout is lower.

He concludes that race is not a statistically significant

variable; in considering race along with the other four just

listed, it only changes the result 6/10 of 1%. Dr. Bullock adds

that being a female increases the likelihood of finishing better

--more so than the effect of race.

Newspaper Endorsements

Dr. Bullock concluded that with one of the two major

newspaper endorsements, the candidate would finish 1.4 places

higher; with both of them, the candidate can expect to finish

2.75 places higher. The two newspapers involved were The Fort

Lauderdale News and the Broward County edition of The Miami Herald.

Problems with Professor de la Garza's Approach

Dr. Bullock sets forth three reasons why Professor

de la Garza's theory is wrong: First, it has an artificial upper

limit. E.g., if every white voter in the city voted for

Commissioner De Graffenreidt, the only black candidate in the

race, but also exercised his option to vote for four other

candidates who necessarily were white, then the white voters

could not be any more disposed favorably towards a black

candidate than to cast a vote for that black candidate. Yet

under De La Garza's theory, you would have a polarization score

of 80 which would indicate racial polarization even under the

Loewen theory. That would be racial polarization under the De La

Garza theory, even though every white voter in the city had voted

for the only black candidate.

The second reason Bullock concludes that De La Garza's

theory is wrong is it depends on the number of minority

candidates in the election, even if the voter attitude remains

constant. Example: Assume there are 100 white voters and of

that 100, 25 will vote for a black candidate every opportunity

they have. The remaining 75 will never vote for a black

candidate. Each voter can cast five ballots, and there will

presumably be a total of 500 ballots cast. If one black

candidate is running, the black candidate gets 25 votes of the

100 white voters, and that would be 25 votes of a total of 500

votes cast which, under the De La Garza approach, gives a

polarization score of 95%. If there are two black candidates

running, the black candidates would get two times 25, or 50 votes

out of the 500 votes cast, which would give a polarization score

according to De La Garza of 90. Similarly, three black

candidates would attract 75 out of 500 votes and the polarization

score would be 85. With four black candidates, the polarization

score falls to 80, and with five black candidates, they get 125

votes, resulting in a polarization score of 75, according to

1 Is

: * . . - . r ^ f c r ' - v T f

De La Garza. Consequently, the attitudes in the white community

in this illustration remain constant. The polarization score

varies tremendously simply because of the number of options

available to vote for black candidates.

In the third illustration, we assume the same voting

attitudes of 100 white voters with 25 of them who will always

vote for a black candidate. What will vary is the number of

candidates the voter can vote for in a race, but only one black

candidate is in each election contest. If you have a

head-to-head race for the U.S. Congress with a black candidate

competing with a white candidate, the 25 votes would end up with

a De La Garza score of 75% polarization. However, in a

hypothetical race for state representative (and the voters in

this precinct can vote for two candidates for state

representative), again, there is only one black candidate

running, then 100 white voters would cast 200 ballots with 25 for

the black candidate and the polarization score has now risen to

87.5%. If in the same election there are three members of the

local school board running at-large, in the same precinct of 100

white voters, the black candidate would get 25 of those,

producing a polarization score of 93.75%. Eventually you get to

five slots to be filled, such as in the Fort Lauderdale City

Commission. The same situation now produces a polarization score

of 95%.

Dr. de la Garza does concede certain problems with his

approach in attempting to determine voter polarization in Fort

Lauderdale with his comment that "you can't translate voter

De La Garza. Consequently, the attitudes in the white community

in this illustration remain constant. The polarization score

varies tremendously simply because of the number of options

available to vote for black candidates.

In the third illustration, we assume the same voting

attitudes of 100 white voters with 25 of them who will always

vote for a black candidate. What will vary is the number of

candidates the voter can vote for in a race, but only one black

candidate is in each election contest. If you have a

head-to-head race for the U.S. Congress with a black candidate

competing with a white candidate, the 25 votes would end up with

a De La Garza score of 75% polarization. However, in a

hypothetical race for state representative (and the voters in

this precinct can vote for two candidates for state

representative), again, there is only one black candidate

running, then 100 white voters would cast 200 ballots with 25 for

the black candidate and the polarization score has now risen to

87.5%. If in the same election there are three members of the

local school board running at-large, in the same precinct of 100

white voters, the black candidate would get 25 of those,

producing a polarization score of 93.75%. Eventually you get to

five slots to be filled, such as in the Fort Lauderdale City

Commission. The same situation now produces a polarization score

of 95%.

Dr. de la Garza does concede certain problems with his

approach in attempting to determine voter polarization in Fort

Lauderdale with his comment that "you can't translate voter

. ; w * \ ± " " . H i jwm w *-

polarization in a conventional sense into this kind of election

system," and "this particular type of at-large election is not

readily quantifiable by political science."

Dr. de la Garza also could not explain, using the

actual example from the 1973 election where there were 31

candidates, only one of whom was black, and if a white voter cast

a vote for the black candidate and four votes for white

candidates, how those votes and that voter are not racially

polarized under his bivariate theory. The nearest thing he could

give as a reason for this apparent flaw in his theory was that

(the white voter should have single-shot (bullet voted) his vote

/ for the one black candidate if he really wanted the candidate to

Comparing the two approaches, the court is left with

very little confidence in the approach of Dr. de la Garza in view

of its apparent ignoring of factors which plainly affect election

results.

The Supreme Court in Teamsters v. U.S., 431 U.S. 234

(1977), cautioned that "...statistics are not irrefutable; they

come in infinite variety and, like any other kind of evidence,

they may be rebutted. In short, their usefulness depends on all

of the surrounding facts and circumstances." Id. at 340.

The Fifth Circuit in Wilkins v. Univ. of Houston, 654

F.2d 388 (5th Cir. 1981), reh'q denied, 662 F.2d 1156 (5th Cir.

1981), repeated its panel opinion statement on rehearing:

_______________/

5/S ingle-shot or bullet voting is to vote for only one— or

perhaps two— candidates in order to give maximum effect to your vote for that candidate.

"multiple regression analysis is a largely sophisticated means of

determining the effect that any number of different factors have

on a particular variable." [Emphasis supplied.] 654 F.2d at

402, 662 F. 2d at 1157. Only one expert testified in the Wilkins

case and introduced a series of independent variables affecting

salary in a discrimination case. These various independent

variables showed that when sex was added as the ninth independent

variable, sex (gender) as a factor explains only .8 of 1% more of

the variation around the average salary (the dependent variable).

when race is added to the other independent variables he applied

to the voting statistics for past city commission races, the

factor of race explains only .6 of 1% of the dependent variables

of candidate success. Consequently, a totality of the evidence,

including Dr. de la Garza's admitted difficulties in applying his

bivariate analysis to the city's at-large election system,

In the instant case, Dr. Bullock's model shows that

compels the conclusion there has been no racial polarization

showing a violation of the Voting Rights Act. 6/

A Voting Rights Act case, Jones v. City of Lubbock., 727

F.2d 364 (5th Cir. 1984), reh'g denied, 730 F.2d 233 (5th Cir.

1984), reveals that the city of Lubbock, Texas, has a total

population only slightly larger than Fort Lauderdale, with a

Mexican-American population of 17.9%, about halfway between Fort

Lauderdale's 1970 black population percentage of 14.6% and its

1980 black population percentage of 21%; additionally, there is

an 8.2% black population in Lubbock which, unlike Fort

Lauderdale, had never elected a minority group member to the city

council, probably because of its majority vote requirement, again

unlike Fort Lauderdale. The demography in Lubbock bears

considerable resemblance to Fort Lauderdale.

Seldom does this court quote at length from any judge's

analysis or opinion, particularly a concurring opinion, but Judge

________________________/

6/In many ways the instant case bears a striking statistical

resemblance— at least in its development— to a case from the pay

discrimination field, Boylan, et al. v. The New York Times. The

Boylan plaintiffs were women employees of The New York Times, but

the heart of the plaintiffs' classes were the female reporters.

They claimed they were discriminated against paywise because of

their gender, and the bivariate analysis based on sex alone

supported their claim dramatically, much like Dr. de la Garza's

bivariate regression analysis on race in the instant case.

However, as other valid independent variables were tested,

such as the number of Pulitzer Prizes won, years of college, work

experience prior to coming to work for The New York Times,

seniority and tenure, etc., the disparity in pay's strong

statistical support had diminished dramatically from what it

appeared to have been at first. Alas, for purposes of this

court's citations, the case settled a few days prior to trial in

the United States District Court for the Southern District of New

York----------

23

Patrick Higginbotham's opinion is most applicable to the instant

case, as follows:

Care must be taken in the factual development of the

existence of polarized voting because whether polarized

voting is present can pivot the legality of at-large

voting districts. The inquiry is whether race or

ethnicity was such a determinant of voting preference

in the rejection of black or brown candidates by a

white majority that the at-large district, with its

components, denied minority voters effective voting

opportunity. In answering the inquiry there is a risk

that a seemingly polarized voting pattern in fact is

only the presence of mathematical correspondence of

race to loss inevitable in such defeats of minority

candidates. The point is that there will almost always be a raw correlation with race in any tailing candidacy"

of a minority whose racial or ethnic qFoup~~l.s mm khih 1 1 •

a percentage of the total voti nq~~pooulation as here.Yet, raw correspondence, even at high levels,must

accommodate the legal principle that the amended Voting

Rights Act does not legislate proportional

detailed findings are required to support any

conclusions of polarized voting. These findings must

make plain that they are supported by more than the

inevitable by-product of a losing candidacy in a

predominately white voting population. Failure to do

so presents an unacceptable risk of requiring

proportional representation, contrary to congressional will.

730 F.2d at 234.

For the third factor considered by the Senate report

and the court in Dallas County, the city has not had a majority

vote requirement or anti-single-shot provisions or any other

voting practices or procedures traditionally used to enhance the

opportunity for discrimination against minority groups or its

black citizens. The city has used at-large elections from the

very beginning of the city, and it was not something that was

incorporated to evade or circumvent the law of the land. As

at-large elections are not prohibited per se by the Voting Rights

Act.7/ United States v. Dallas County Commission, 739 F.2d

at 1534 (11th Cir. 1984), this court finds no error in the

continued use of the at-large system.

The fourth factor is whether there is a candidate

slating process. There is not one in the city and no evidence

has been adduced to that effect. Plaintiffs made an effort to

intimate that the Broward Citizens Committee was a slating

process under this factor. The Broward Citizens Committee is a

group that interviews candidates but it recommends only

Republicans, even though the city election is officially

nonpartisan. This court cannot conclude from the evidence that

it is necessary for a candidate to receive approval from the

Broward Citizens Committee before success is enhanced or assured

in the city elections. The evidence does not show that even one

of the black candidates who has run for the Fort Lauderdale City■ -— —--

Commission is a Republican. Inasmuch as former Mayor and

____________________/

7/In fact, court after court has explicitly avoided such a

holding: United States v. Dallas Countv Commission, 739 F.2d at1534 ( 11th Cir~i 19B4); United States v.Marenao County Commission, 731 F.2d at“T563 "(11th Cir. 19 84 ). See also Rogers

v. Lodge, 458 U.S. 613 (1982); Brown v. Bd. of School Com'rs of

Mobile County, Ala,, 706 F.2d at 1104 (11th Cir. 1983 ) ;-------- “

N^A.A.C.P. v. Gadsen County School Board, 691 F.2d at 981 (11th Cir. 1982).

long-time Commissioner Virginia Young does not receive the

recommendation of the Broward Citizens Committee— despite her

generally being regarded as a conservative in

politics®/— one must conclude that this unofficial

organization®/ simply furthers the interest of candidates who

are Republicans. There are and have been prominent black

citizens of Fort Lauderdale who are Republican^ but no evidence

has been offered to indicate they ever sought the recommendation

of the Broward Citizens Committee.

The fifth factor is the extent of the effects, if any,

of discrimination in areas such as education, employment, and

health on minority group members, "which hinder their ability to

participate effectively in the political process."

Dr. de la Garza, plaintiffs' expert, testified that in

nine of the twelve elections from 1971 to 1982, inclusive, black

"turnout is equal to or higher than white turnout." In the other

three elections, white turnout exceeded black turnout by less

than 1% in two of them, and in only one election did white voter

turnout exceed that of the black voters by as much as 2% (22% to

20%). However, in five straight elections black voter turnout

was larger by more than 8%, occasionally as much as 17%.

Consequently, although the court received evidence presented by

plaintiff in these areas, the qualification in the Senate report

____________________/

®/See, e.g., testimony of Arthur Kennedy.

____________________/

®/The testimony as to whether it is a registered political organization was inconclusive.

of effects "which hinder their ability to participate effectively

in the political process" makes such evidence irrelevant as a

practical matter.

Nevertheless, the court has considered whether any

effects of discrimination — or lingering effects — in the field of

education would adversely affect political participation.10/

The statistics referred to in Professor de la Garza's testimony

indicate it did not affect the turnout of the black voters.

The court has even contemplated whether any lingering

effects of education discrimination would affect the quality of

the black candidates. That does not appear to have been the

case: Alcee Hastings was a lawyer at the time of his candidacy;

Commissioner De Graffenreidt was an experienced educator and past

Classroom Teacher of the Year; Art Kennedy was a high school

coach and president of the county's Classroom Teachers

Association, while Louis Alston was a college student at the time

of his candidacy.

________________________/

10/The school system is not maintained on a citywide basis.

It is operated by a county school board so the City of Fort

Lauderdale has no control or voice in the operation of the

schools, including assignment of students or equality of

instruction. There have been no schools built in the white

residential areas of Fort Lauderdale since the 1960's, largely

because the population centers— particularly for young

families have moved to the western portion of the county, except

for the largely childless condominium dwellers along the beach

and Intracoastal. A second factor troubled the court about

plaintiffs' expert testimony on education: he had not included

the high school sitting immediately outside the city limits of

Fort Lauderdale (Northeast High School), which high school

services a large population area of Fort Lauderdale. However, in his statistics, he included several other schools not located in the city.

.* .•JvV'*-

There was one area which might conceivably affect the

participation in the political process, and that is a disparity

1969, the median income was $7,674 for white families and $4,626

for black. In 1979, the figures were $15,410 and $9,761,

respectively. ^

contributions, although Art Kennedy had virtually no trouble

securing contributions.

The matter of employment listed in the Senate report

seems subsumed in income.

Again, except as indicated above, there seems no effect

in ability to participate equally.

Sixth, whether past political campaigns have been

characterized by overt or subtle racial appeals. No evidence has

been introduced in this trial which would begin to suggest there

has been any such tactic in political campaigns in the past. On

the contrary, there was evidence that the commissioners in the

mid-70s ran as a "team" and that Commissioner De Graffenreidt was

a member of the team. In addition, in the 1982 election, Arthur

Kennedy testified that he and the present mayor, Robert Dressier,

urged voters to vote for both of them.

group members have been elected to public office in the city. In

view of the parties' concentration on the six elections since

197C, the court has largely limited its consideration of

elections to that period as well. There has been a black

in income among white residents vis-a-vis black residents.

This differential conceivably could affect

The seventh factor is the extent to which minority

28

candidate in every election, and two in 1982. In the elections

with "open seats"— there have been four "open seats," one in

1971, two in 1973, and one in 1982— there has been one black

candidate, Andrew De Graffenreidt, elected, and another who

narrowly lost, Art Kennedy in 1982. Kennedy lost by 568 votes

out of 17,151 cast, for a margin of defeat amounting to 3.29%.

This factor was covered in greater detail earlier.

After all, the proof is in the pudding. This court dealt with

this factor at the beginning because it feels this factor is by

far the most important of the nine listed by the Senate and Court

of Appeals. E.g., if the other eight factors show no reason even

to suspect a violative condition under the Voting Rights Act, but

minority candidates have had little or no chance of election

despite numbers to indicate electoral strength, the minority

group may well be able to show a violation. Conversely, if the

minority group is having success at the polls— especially if

the success exceeds its statistical electoral strength— then a

strong showing in all the other factors could scarcely justify

relief to that group.

The two additional factors set forth in the Senate

report may deal more exclusively with the issue of intent but

will be addressed by this court anyway, despite the amendment of

the Voting Rights Act. The eighth factor is whether there is a

significant lack of responsiveness on the part of elected

officials to the needs of the minority group members. Most of

the evidence on this factor was introduced by the city. For

example, the city called the city recruiting officer, who is in

3 9

. : ' . . V i *

charge of the minority recruiting program, particularly for

police and fire department positions. Not only do they use radio

advertising, but he, along with a police officer, goes to various

community functions, community colleges around the state and

country in recruiting efforts.

The city has been operating under a 1980 consent decree

to achieve 11.25% black fire fighters and police officers. By

1982, the city had achieved a 12.9% figure of its fire fighters

who were black. The same goal was set for the police department

(based on the 1970 census), but in 1982 the city was only at a 6%

manning level.

The city had validated its police entrance examination

in 1977 and it was considered valid. A new recruiting officer

adopted a new test in 1982 to increase the passing rate for

minorities from 18% to 25%, and currently it is in excess of 50%.

The explanation for being below 11.25% in police officers results

largely because 15 minority police officers left. Apparently a

number of cities are under the stimulus of a consent decree in

minority hiring and are raiding each other's police departments

in the sense of offering attractive benefits to minority officers.

Fort Lauderdale's salary and benefits program became competitive,

perhaps attractive, in mid-1984.

The city has been engaged in a recruiting program

attempting to add minorities to the police and fire departments

for several years prior to the consent decree in 1980,

particularly in the area of public service aides who then moved

into the police departments or fire departments.

30

Unfortunately, a reverse discrimination suit was filed

by white police officers in federal court, and that has resulted

in an injunction against any further promotional testing for the

rank of police sergeant, thereby freezing the situation as of a

previous promotion list.

In 1979, Commissioner De Grafenreidt was reported in

The Miami Herald to have said that the city has done everything

possible with respect to minority hiring.

The city also called Assistant City Manager James Hill,

who happens to be black and has been the assistant city manager

since 1970. He is the affirmative action officer for the city in

addition to his other duties.

The city engineer testified that Fort Lauderdale still

does not have sanitary sewers in all of the areas within the city

limits. Because of Fort Lauderdale's sandy soils and low

population in the past, sanitary sewers were not the compelling

need they may become in the future. A program was developed and

instituted to install sanitary sewers, generally working from the

ocean westward. In 1970, a consultant performed a master plan

for sewers for the city of Fort Lauderdale, and the city

anticipated having all of the city furnished with sanitary sewers

by sometime in 1975 or 1976. However, about the time of the

"master plan," EPA came into existence and ordered the cessation

of gravity sanitary sewers, changing the entire treatment

process, treatment plant locations in Fort Lauderdale, and doing

away with all treatment plants which contributed effluence

into the waterways. (The court can take notice that more than

31

200 miles of canals and waterways exist in the city of Fort

Lauderdale.) These sanitary sewer-deficient areas are in both

the black and white sections of the city, primarily in the

southwest section (largely white), with some in the northwest,

but only very small portions in the northeast or southeast

quadrants of the city.

The city engineer further testified that procedure for

installing sanitary sewers is that a petition is filed by the

residents of a neighborhood requesting installation of sewers and

installation recommendations depend on certain engineering

factors, such as hydraulic design, etc. The city commission

receives various technical data from the engineering department

and then holds public hearings in passing a resolution declaring

the necessity of installation, and the cost of the assessment is

made against the individual property owners. A procedure has

been implemented whereby the payments can be spread over several

years at simple interest in order to accommodate the low income

homeowner. However, septic tanks work fairly well in Fort

Lauderdale's sandy soil; none of the predominantly black areas,

which are still unsewered, have petitioned for sanitary sewers.

The last unpaved street in Fort Lauderdale was paved

about six months prior to the hearing and it was in a white

neighborhood .

The city also called its deputy personnel director who

outlined the efforts made by the city to recruit minority

employees into the city's work force. They are spending about

$100,000 to $150,000 a year in that area alone: up to $20,000 a

32

year for advertising, and the balance on recruiting trips to

other cities attempting to recruit personnel.

Evidence was also received as to promotion of black

city employees vis-a-vis white city employees. In 1981, although

there were more white employees promoted, the percentage of

eligible whites promoted was 48% while the percentage of eligible

blacks promoted was 95%. Similar situations continued on into

both 1982 and 1983, as well as the first part of 1984.

There still is an average income disparity, but this

matter was naturally not the subject of statistical treatment by

either side. There were fewer blacks, for example, in the

engineering department and no breakdown was given as to the

effect of seniority and tenure on compensation. Consequently,

the compensation matter seems to have some similarity to the

Fifth Circuit case of Wilkins v. Univ. of Houston, supra.

Since the year before the consent decree, the city has

hired 2,000 employees, 22% of them black.

The city also presented evidence as to code compliance

with the minimum housing codes.

Without the impetus of a consent decree, the city

commission ordered a part of the northwest section of the city

(largely black) in October of 1982 to be upgraded and an

equivalent of one inspector assigned on a full-time basis to

concentrate on that area.

The director of parks and recreation for the city

testified that 550 acres of parks exist in Fort Lauderdale,

ranging from small "vest-pocket parks" to Fort Lauderdale Beach.

There is no line of hotels or motels separating the public from

Fort Lauderdale's beaches as exists in many other Florida cities.

There has been no question the city's beach has been integrated,

at least since 1961. Of the 550 total acres, 190 acres (32% of

the total) of the parks are situated in the northwest section

(largely black). However, a portion of that 190 acres was

acquired several years ago by the city for a park but has not

yet been developed. The parks in the white neighborhood areas of

the city are not only integrated, but are freely used by black

persons. The major parks in the city have full-time recreation

program staff members.

The city also introduced evidence as to the use of the

Community Development Grant funds, which have been receivd by the

city basically since 1974. In this 10-year period, Fort

Lauderdale has received almost $21,400,000. Of that figure, 90%

to 95% of the funds have been spent in the northwest sector. The

unds have been used for matters such as construction of the Dr.

Von Mizell Center, rehabilitation and modernization of public

housing, renovation of their low-income housing, rental

rehabilitation program, etc.

The totality of evidence indicates that the

responsiveness of the city is hardly perfect, but most of the

inequities that exist are from difficulties in recruiting

competition in the police department area. There the city has

made bona fide and intensive efforts to overcome the problems of

recruiting or retention. Another area of difficulty is the

disparity in income of city employees, much of which results from

seniority factor of employees who have been with the city for up

to 20 or 30 years. The evidence does persuade the court that the

city has made intensive efforts, certainly in the last 10 to 15

years, to correct any imbalances and has been ̂ overcompensatT 57

during that period of time in many programs in an effort to

improve and correct any imbalance.

The ninth factor deals with the tenuousness, if any, of

the policy underlying the use of any voting qualification

practice or procedure. There is no questionable voting

prerequisite or procedure involved in this case. The only

question has been whether the city's at-large system itself

violates the Voting Rights Act. The city has had the at-large

system since its creation in 1911, and this court does not find

from the totality of evidence indications that its election

policy either was adopted or has been maintained to discriminate

against minority citizens.

Summary

This court has gone through the nine factors indicated

as being relevant by the Senate as well as the Court of Appeals.

The totality of the evidence does not warrant a finding that Fort

Lauderdale's at-large system of electing commissioners, with the

highest vote-getter becoming the mayor, violates the Voting

Rights Act, as amended.

Fort Lauderdale simply has very little resemblance to

the many cases which have held a violation of the Voting Rights

Act. Fort Lauderdale, with a black population of 14.6% in 1970

which had climbed to 21% by 1980 because of a plateauing of the

white population, has elected a black commissioner three times in

the six recent elections. The leading cases are decidedly

different by comparison: Rogers v. Lodge, 458 U.S. 613 (1982),

where the black population of Burke County, Georgia, was 53.6%

while only 38% of the registered voters comprised black voters

and no black had ever been elected to the board of county

commissioners; United States v, Marengo County Commission, 731

F.2d at 1563 (11th Cir. 1984), had a black population in the

county of 55.2% and 44% of the registered voters were black, but

the only black ever elected to county office was a county coroner.

In N.A.A.C.P. v. Gadsden County (Florida) School Board, 691 F.2d

at 981 (11th Cir. 1982), the county population was 59% black with

49.36% registered voters being black, but only one black had ever

been elected to the school board. In United States v. Dallas

_Commi s s i on, 739 F. 2d 1529 (11th Cir. 1984), the population

of Dallas County, Alabama, was 52.3% black, while 43.8% of the

registered voters were black, but no blacks in recent history had

ever been elected to any county office.

The equal opportunity to participate in a political

process and to elect representatives of their choice is best

shown at the polls. All parties, lawyers, experts, witnesses, et

al., agree that an "open seat" affords the best chance for a

candidate to be elected. There have been four open seats since

1970 (only one since 1973), and a black candidate won one of

36

them.H/ Considering the minority percentage population in

1970 of 14.6%, one out of four would be comfortably above a

proportional representation figure— even if that were not

specifically proscribed by Congress. If Mr. Kennedy had won in

1982, this lawsuit would be illogical and would be virtually

frivolous under these circumstances. As it turns out, he lost by

a mere 3.2% and attributes his defeat to an election eve letter

on the letterhead of the county Republican party urging Fort

Lauderdale citizens to vote for four Republicans and his failure

to respond to it.

If one examines it another way, the result does not

vary: Since 1970 (counting the 1979 mayoralty race), there have

been 75 white candidacies for city commission, of which 27 were

successful in being elected, for a percentage of 36%, while there

have been seven black candidacies, of which three were

successful, for a percentage of 43%.

What has emerged from the evidence is that the bulk of—— _____

Fort Lauderdale citizens are conservative, largely Republican.

Although the city races are officially nonpartisan, the city

commission has been Republican for approximately two decades.

Not one of the black candidates has been a Republican according

to the evidence.

What has also emerged from the evidence is that the

white voters of this city are more than willing to vote for black

____________________/

H/With two "open seats" in 1973 and only one black

candidate, it would have been impossible for black candidates to win more than three.

candidates. For example, Commissioner De Graffenreidt would have

won re-election in 1975 and 1977 on votes from white precincts

alone. In addition, in 15 non-city races, e.g., for Florida

Supreme Court Justice, Florida Public Service Commission, and the

county commission, the white voters of Fort Lauderdale in four

different races have given a majority vote to a black candidate

who was competing with a white candidate, and in four other

elections, black candidates received 40% to 49.9% of the white

vote.

The evidence fails to show a violation of the Voting

Rights Act in Fort Lauderdale's at-large system for its city

commission.

Order to be entered accordingly.

DONE AND ORDERED at Fort Lauderdale, Florida, this/ £ *

Copies to:

3 *

C • *’’! -1 • i " H T f l lM I X