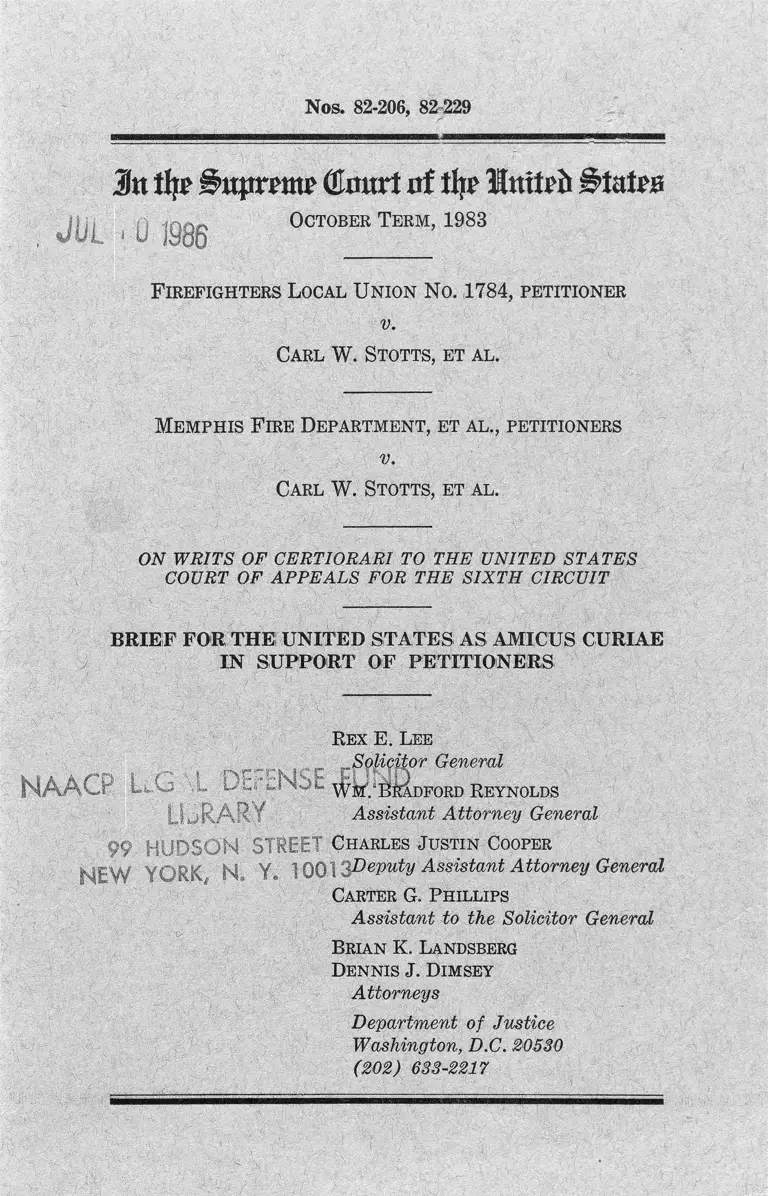

Firefighters Local Union No. 1784 v. Stotts Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Petitioners

Public Court Documents

August 1, 1983

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Firefighters Local Union No. 1784 v. Stotts Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Petitioners, 1983. f94688c6-b19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/bbdd4047-4445-43fe-8bd2-c927e961fce3/firefighters-local-union-no-1784-v-stotts-brief-amicus-curiae-in-support-of-petitioners. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

Nos. 82-206, 82 229

In % Bnprmt (Urntrt of % HHmUb States

October Term, 1983

F irefighters Local Union No. 1784, petitioner

v.

Carl W. Stotts, et al.

Memphis F ire Department, et al., petitioners

v.

Carl W. Stotts, et al .

ON WRITS OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE,: UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE

IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS

NAACP

Rex E. Che

.,„Sg}icitor General

tNu'E Reynolds

■jRARY Assistant Attorney General

’ 99 : HUDSON STREET Charles Justin Cooper

NEW YORK N, Y. 10013P eVwby Assistant Attorney General

Carter G. Phillips

Assistant to the Solicitor General

Brian K. Landsberg

Dennis J. Dimsey

Attorneys

Department of Justice

Washington, D.C. 20530

(202) 633-2217

QUESTION PRESENTED

This brief will address the following question:

Whether the district court exceeded its authority by

prohibiting the City of Memphis from laying off and

demoting personnel in its fire department on the basis

of accumulated seniority in order to maintain the per

centage of minority employees in the department who

had been hired and promoted pursuant to a consent de

cree entered into as a settlement of suits charging

discrimination in the department’s hiring and promotion

practices.

(I)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Interest of the United States................ ......-...................... 1

Statement ..... ............... ............ .............................................. 2

Summary of Argument ............... -................. ...................... 8

Argument:

The district court’s order exceeded its remedial

authority under Section 706(g) of Title V I I ........ 11

A. The order o f the district court disregards the

important statutory policy embodied in Section

703(h), 42 U.S.C. 2000e-2(h), to protect sen

iority systems, ignores the legitimate interests

of incumbent employees in those systems and

grants unwarranted protection to non-victims

of discrimination....................... 13

B. The limitation on the court’s remedial author

ity contained in the last sentence of Section

706(g) confirms that Congress did not intend

to grant constructive seniority in the circum

stances of this case........................ .......................- 23

C. The courts below should have avoided creating

a substantial constitutional question by refrain

ing from issuing a race conscious seniority or

der that was not clearly intended by Congress

in Title VII .............................................................. 29

Conclusion ................................ 31

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Aetna Life Insurance Co. V. Haworth, 300 U.S.

227 ......... ............. -.......-............ -............................... - 8

Airline Stewards & Stewardesses Association V.

American Airlines, 573 F.2d 960, cert, denied,

439 U.S. 876 _______ _______ _________________ - 18, 19

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 ____15, 24,

29,30

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 3 6 ___ 12

Page

(III)

American Tobacco Co. v. Patterson, 456 U.S. 63..... 9, 13,

14, 25

Arizona Governing Committee V. Norris, No. 82,-

52 (July 6, 1983) ______ .________ ______ ______ 16,18

Boston Firefighters Union V. Boston Chapter,

NAACP, No. 82-185 (May 16, 1983) .................... 8

Buckley V. Valeo, 424 U.S, 1 ...................... .............. 29

California Brewers Association V. Bryant, 444 U.S.

598 ...........................................................................13, 14-15

Carson V. American Brands, Inc., 450 U.S. 7 9 ..... 12

Connecticut V. Teal, 457 U.S. 440 ...._.................... 9,16

County of Los Angeles V. Davis, 440 U.S. 62:5....... 8

Delaware & II. Ry. V. United Transportation Union,

450 F.2d 603, cert, denied, 403 U.S. 911 .............. . 28

Ford Motor Co. V. EEOC, No. 81-300 (June 28,

1982) .......................... .................... 8,13,18,19, 21, 24, 30

Franks V. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S.

747 ........................................... ........9,15, 16, 24, 28, 29, 30

Fullilove v. Klutznick, 448 U.S. 448 .............. .......... . 30

General Building Contractors Association v. Penn

sylvania, No. 81-280 (June 29, 1982) ................ 11-12

Griggs V. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 ................ . 11, 17

H.K. Porter Co. V. NLRB, 397 U.S. 99 .................... 13

Humphrey V. Moore, 375 U.S. 335 ......................... . 8, 13

Local 189, United Papermakers and Paperworkers

V. United States, 416 F.2d 980 ..................... ....... 18

Los Angeles Department of Water & Power V.

Manhart, 435 U.S. 702 ......................................... 16

Minnick V. California Department of Corrections,

452 U.S. 105 ................................. ............. .............. 31

Moragne V. States Marine Lines, Inc., 398 U.S.

375 ....... ............................................. ......................... 13

Morton V. Mancari, 417 U.S. 535 ...... ........................ 31

NLRB V. Catholic Bishop, 440 U.S. 490 ......... 10, 31

Occidental Life Insurance Co. v. EEOC, 432 U.S.

355 _____ ____ ___ ________ ___ ___ ________ ___ _ 12

O’Connor v. Board of Education, 645 F.2d 578,

cert, denied, 454 U.S. 1084 ____ _____ ________ __ 23

Patterson v. American Tobacco Co., 535 F.2d 257..9-10,18

Powell V. McCormack, 395 U.S. 488 _____________ 8

Punnett V. Carter, 621 F.2d 578 ............................ 23

IV

Cases— Continued Page

Regents v. Bakke, 488 U.S. 265 ....1........................... 30

System Federation V. Wright, 364 U.S. 642 __ ..... 12

Teamsters V. United States, 431 U.S. 324 ............passim

Trans World Airlines, Inc. V. Hardison, 432 U.S.

63 ................................................................................ 9, 13

United A ir Lines, Inc. V. Evans, 431 U.S. 553....... 14

United States V. Int’l Union of Elevator Construc

tors, 538 F.2d 1012 .................... .......................... 28

United States V. Security Industrial Bank, No. 81-

184 (Nov. 30, 1982) ................................................. 10, 31

United States V. W. T. Grant Co., 345 U.S. 629 .... 8

United Steelworkers V. Weber, 443 U.S. 193 ....... 22

Virginia, Ex parte, 100 U.S. 339 ............... ....... . 29

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 .................... . 11

Withrow V. Larkin, 421 U.S. 35 .......................... ;.... 23

W. R. Grace & Co. V. Local 759, No. 81-1314 (May

31, 1983) ............................... ....................... ......... . 12,22

Constitution and Statutes:

United States Constitution :

Amend. V (Due Process Clause) __ __________ 10, 29

Amend. X I V ..... ........... ........ ................................ 29

§ 5 .................................................... ............... 10, 30

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title VII, 42 U.S.C. (&

Supp. V) 2000e et seq............................................. 1, 8

Section 703, 42 U.S.C. 2000e-2.......................... 27

Section 703 (a ) , 42 U.S.C. 2000e-2 (a) .............. 15

Section 703(h), 42 U.S.C. 2000e-2(h) .....9,13, 14, 18

Section 706(f) (1 ), 42 U.S.C. 2000e-5(f) (1) .. 1

Section 706(g), 42 U.S.C. 2000e-5(g) .......10, 12, 13,

17, 18, 19, 23-29

42 U.S.C. 1981 ................................ ............ ................ 2, 11

42 U.S.C. 1983 ................ .............. .............. ......... ....... 2, 11

Miscellaneous:

Comment, Preferential Relief Under Title VII, 65

Va. L. Rev. 729 (1979) ................. .............. ........... 25

110 Cong. Rec. (1964) :

pp. 486-487 .................................................... ....... 14

pp. 486-489 .... ................ .............. ........................ 9

V

Cases— Continued Page

VI

Miscellaneous— Continued Page

p. 1518 .......................................... 25

p. 1540 ................................. 25

p. 1600 .................... ............... ................................ 25

p. 2567 ..................... ............. ................................. 25

p. 5423 ...... .................................. ............ ............ - 25

p. 6549 .............................. ..................... ............. . 26

p. 6563 .......................................... ............ .......................... ............. 26

p. 6566 ........................... ........................................ 25

p. 7207 ..................................................... .............. 14,26

pp. 7212-7215 .................. 14

p. 7214 .............. ;.™„............. .................... ....... 26

pp. 7216-7217 ........................................................ 14

p. 12723 - .................. ................ ........................... 14

pp. 12818-12819 ................................ ........... ........ 14

p. 14465 __________ ______ ___ ______ ______:... 26

118 Cong. Rec. (1972):

p. 1662 ........................................... ......... .......... 28

pp. 1663-1664 ..................... 28

p. 4917 ...........................!................................. . 28

pp. 4917-4918 ...... ................. ........... ............ ....... 28

p. 7168 ...................................... ........... ......... ;........ 15,28

p. 7565 ............................... 28

H.R. 1746, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. (1972) .......... ......... 28

H.R. Conf. Rep. No. 92-899, 92d Cong., 2d Sess.

(1972) _______ 28

H.R. Rep. No. 914, 88th Cong., 1st Sess. (1963) ... 14

S. 2515, 92d Cong., 2d Sess. (1972) ................... . 28

S. Conf. Rep. No. 92-681, 92d Cong., 2d Sess.

(1972) ....... 28

Subcomm. on Labor o f the Senate Comm, on Labor

and Public Welfare, 92d Cong., 2d Sess., Legis

lative History of the Equal Employment Oppor

tunity Act of 1972 (Comm. Print 1972) ______ 18, 27,

28, 29

In % (tmxxt nf % Itttteft States

October Term, 1983

No. 82-206

F irefighters Local Union No. 1784, petitioner

v.

Carl W. Stotts, et a l .

No. 82-229

Memphis F ire Department, et al., petitioners

v.

Carl W. Stotts, et al.

ON WRITS OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE

IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS

INTEREST OF THE UNITED STATES

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

(& Supp. V) 2000e et seq., prohibits, inter alia, racial

discrimination in employment. The Attorney General is

responsible for the enforcement of Title VII in eases such

as this one where the employer is a government, govern

mental agency, or political subdivision. 42 U.S.C. 2000e-5

(f) (1). This Court’s resolution of the issue presented in

this case, viz., the propriety of a preliminary injunction

requiring that layoffs and demotions of city employees

be made not on the basis of a bona fide seniority system,

( 1 )

2

but rather pursuant to a modified seniority system de

signed to assure that recently hired and promoted mi

nority employees retain their positions, will have a sub

stantial effect on the Attorney General’s enforcement

responsibilities under Title VII.

STATEMENT

1. In February 1977, Carl Stotts, a black Captain in

the Memphis Fire Department, filed suit in the United

States District Court for the Western District of Ten

nessee against the City of Memphis, the City’s Director

of Personnel, the Memphis Fire Department, and the

Department’s Director of Fire Services. The complaint,

styled as a class action, alleged that the defendants had

engaged in racially discriminatory hiring and promotion

practices, in violation of Title VII of the 1964 Civil

Rights Act and 42 U.S.C. 1981 and 1983 (Pet. App.

A 4).1 2

In June 1979, Fred Jones, a black Private in the Fire

Department, filed an individual action in the same dis

trict court under Title VII and 42 U.S.C. 1983 against

the same defendants. Jones alleged in his complaint that

he had been denied a promotion to the rank of Fire In

spector because of his race. In September 1979, the dis

trict court ordered the cases consolidated (Pet. App.

A5) ?

Subsequently, in April 1980, all of the parties to the

consolidated cases agreed to a settlement, which was ap

proved by the district court. In the decree, the City did

not admit to having violated any laws; nevertheless it

committed itself to a long-term goal of increasing mi

nority representation in each job classification in the De-

1 “ Pet, App.” refers to the appendix to the petition for a writ of

certiorari in No. 82-206.

2 Neither of the complaints raised any issue with respect to lay

offs or demotions within the Department.

3

partment to levels approximating the level of minority

representation in the local labor force.®

The decree also established a 50% interim hiring goal

and 20% interim promotion goal for qualified minori

ties.* 4 Except for a general commitment by the City not

to discriminate on the basis of race “with respect to com

pensation, terms and conditions or privileges of employ

ment” (id. at A62), the decree was silent as to the

manner in which any layoffs or demotions in the De

partment were to be conducted.

2. On May 4, 1981, the City announced that for the

first time in its history projected budget deficits required

personnel reductions in all major departments. The re

ductions were to be made on the basis of city-wide sen

iority (Pet. App. A8). Although the City had no formal

8 The City had committed itself to the same long-term goal in a

consent decree entered into with the United States in 1974 in

litigation involving allegations of employment discrimination in

violation of Title VII in various city agencies, including the; Mem

phis Fire Department. The City did not admit any misconduct

in that decree, but did acknowledge that its employment practices

gave rise to> an inference! of race and sex discrimination (Pet. App.

A3).

According to the evidence presented at the preliminary injunc

tion hearing held in 1980, 56% of the persons newly hired by the

Department since the entry of the 1974 consent decree have been

black (46% including rehires), and 16-17% of the promotions in

the Department since that time have gone to' blacks (J.A. 48,

57). In 1974, blacks constituted about 32% of the labor force in

Shelby County, Tennessee, and approximately 3-4% of the Fire

Department (J.A. 47). By 1980, blacks constituted approximately

35% of the labor force in Shelby County (Pet. App. A22 & n.14),

and about 10% of the employees in the Fire Department (id. at

A9 n.5).

4 The decree provided that “ [gjoals established herein are to- be

interpreted as objectives which require reasonable, good faith efforts

on the part of the City, and not as rigid quotas” (Pet. App. A64).

It explained further that “ [njothing in this * * * Decree should be

construed in such a way to require the. promotion of the un

qualified or the promotion of the less-qualified over the more

qualified as determined by standards shown to be valid and non-

discriminatory * * *” (id. at A65) .

collective bargaining agreements with any of the unions

representing its employees, the City had entered into

“ memoranda of understanding” with the unions, includ

ing the petitioner union in this case (J.A. 116-119).

These memoranda provided generally for terms and con

ditions of employment with the City; the memorandum

covering the Fire Department provided that “ [i]n the

event it becomes necessary to reduce the Fire Division, sen

iority * * * shall govern layoffs and recalls” (J.A. 119).

The last-hired, first-fired policy adopted by the City for

conducting its proposed layoffs was chosen because of the

memoranda of understanding (id. at 49 ).

On the day the layoff program was announced, the

district court granted respondents’ application for a

temporary restraining order prohibiting the City from

laying off or demoting® any minority employee in the

Fire Department (J.A. 23). Petitioner Firefighters Local

Union No. 1784 was then permitted to intervene with the

consent of the parties (Pet. App. A 8 ).

On May 8, 1981, the court held a hearing on respond

ents’ motion for a preliminary injunction. In order to

stay within its budget, the Fire Department proposed to

eliminate approximately 55 positions in which there were

current employees (J.A. 51). It estimated that the lay

off process would result in a reduction in the percentage

of black employees in the Fire Department from ap

proximately 11% to 10% (J.A. 54).

Of the 55 positions to be eliminated, most were in the

firefighting bureau in the Department (J.A. 52-53, 73,

96-97). The City anticipated that the temporary demo

tions would result in the percentage of black Lieutenants

in the Department being reduced from 12.1% to 6.3%;5 * * 8

5 Under the layoff program, Fire Department employees in ranks

above Private who were scheduled to be: laid off were afforded the

option, if they were qualified to do sb , o f accepting a demotion,

thereby “bumping” a junior employee in the lower rank (J.A. 38-

39,64-65).

« Before the scheduled demotions, 29 of the Department’s 240

Lieutenants were black; after the demotions, 14 of 224 Lieutenants

would have been black (Pet. App. A75; J.A. 21).

4

5

and that of black drivers from 4.8% to 4.2% 1 * * * * * 7 (J.A. 96-

97; Pet. App. A l l n.5). In the fire fighting bureau, an

additional 16 or 17 Private positions were to be elim

inated, but the record does not reflect the race of the

persons occupying those positions (J.A. 67),

The City estimated that, as a result of layoffs, 52 per

sons in the Fire Department would be furloughed, of

whom 32 (or 61.4%) would be white and 20 (or 38.6%)

black (J.A. 65-72). The Mayor of the City testified that

he anticipated that attrition would result in restoring de

moted or furloughed employees to their former positions

within six months to two years (J.A. 39).

3. On May 18, 1981, the district court entered an

order granting a preliminary injunction against the

City’s proposed layoffs (Pet. App. A77-A79). The court

found that the 1974 and 1980 consent decrees did not ad

dress layoffs or demotions, and that memoranda of un

derstanding between the City and the petitioner union

specified that layoffs in the Fire Department were to be

made on the basis of city-wide seniority {id. at A77-

A78).8 9 The court further found that the City’s layoff

plan was not adopted with the purpose or intent to dis

criminate on the basis of race, but that the effect of

these layoffs and reductions in rank is “ discriminatory”

{id. at A78).s Based on this finding, the court concluded

that the layoff program “ is not a bona fide seniority

system” {ibid.}.

1 Before the demotions, 15 of the Department's 311 Drivers were

black; after the demotions, 13 o f 299 Drivers would have been black

(Pet. App. A75; J.A. 21, 96-97). Although 8 black Drivers were to

be demoted to Private, 6 black Lieutenants were to be demoted to

Driver (J.A. 96). Thus the number o f black Drivers would have

been reduced by only two as a result of the planned demotions.

s The court characterized the legal effect of the memoranda under

Tennessee law as “uncertain” (Pet. App. A78).

9 The district court made no findings concerning the statistical

impact of the City’s layoff program upon minorities either in the

Department generally or at any of the various ranks in the De

partment.

6

The district court ordered “ the defendants not [to]

apply the seniority policy proposed insofar as it will de

crease the percentage of black lieutenants, drivers, in

spectors and privates that are presently employed in the

Memphis Fire Department” (ibid,.). The court later ex

panded its injunction to include the positions of Fire

Alarm Operator I, Fire Prevention Supervisor and Clerk

Typist (id. at A12).

4. The court of appeals affirmed (Pet. App. A1-A51).

The court of appeals agreed with the district court that

the City’s layoff plan would have a disproportionate ad

verse effect upon minorities in the Department (id. at

A8). In light of the district court’s unchallenged finding

that the City’s layoff policy was not adopted with a

racially discriminatory purpose, however, the court of

appeals set aside the lower court’s ruling that the layoff

program was not a bona fide seniority system (id. at

A l l n.6, A 4 1 ).10

The court defined the principal issue on appeal as

“whether the district court erred in modifying the 1980

Decree to prevent minority employment from being

affected disproportionately by unanticipated layoffs” (id.

at A 12). In deciding that issue the court of appeals first

considered whether the 1980 Decree itself was reason

able. It found that the temporary hiring and promotion

goals were reasonable and did not unduly abridge the in

terests of incumbent employees, and therefore were con

stitutional. Furthermore, the majority held that the dis

trict court had conducted an adequate hearing before

approving the consent decree (Pet. App. A14-A23).

The court next considered whether modification of the

consent decree was proper under general contract princi

ples. Under this theory the court held that the modifica

tion was permissible because the “ City contracted” to pro

vide “a substantial increase in the number of minorities

10 The court found it unnecessary to resolve the question whether

the memorandum of understanding between the City and the Union

was enforceable under Tennessee law (Pet. App. A38 n.20).

7

in supervisory positions” (Pet. App. A32) and the layoffs

would be a breach of the contract. The district court’s

modification of the decree merely relieved the City of the

full burden that compliance with its contract would have

caused {id. at A34).

Alternatively, the court of appeals held that the district

court could modify the decree to adapt to an unforesee

able change in circumstances. The court upheld the dis

trict court’s general findings that the City’s economic

crisis was unanticipated and that the layoffs would undo

much of the effect of the affirmative relief in the 1980

decree (Pet. App. A57).

Finally, the court considered the effect of seniority

rights on the authority of the district court to protect

minorities from layoffs. The court held that a consent

decree remedying violations of federal law can modify

collective bargaining agreements, including their seniority

provisions (Pet. App. A38-A45).

Judge Martin concurred in part and dissented in part

(Pet. App. A46-A51). He agreed generally with the

majority that the district court did not abuse its discre

tion in granting a preliminary injunction; however, he

disagreed with virtually every specific holding of the ma

jority. He disagreed that the consent decree read as a

contract could be construed to require modification of the

City’s seniority system {id. at A46) ; he rejected the hold

ing that the district court had authority to abrogate the

union’s contractual and statutory rights {id. at A48) ; and

he dissented from the majority’s approval of the under

lying consent decree and rejection of the union’s alterna

tive proposals on the ground that those issues were not

properly before the court {id. at A49-A50). Finally, he

dissented from the “ sua sponte conclusion [of the ma

jority] that the decree is ‘constitutional.’ ” {id. at A50).11

11 According to respondents’ suggestion of mootness and peti

tioners’ joint response thereto, all of the firefighters who were laid

8

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

1. This Court has repeatedly held that in exercising

the equitable authority granted in Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. (& Supp. V) 2000e et seq.,

courts are limited by the general policies and overall ob

jectives of the Act. See, e.g., Ford Motor Go. v. EEOC,

No. 81-300 (June 28, 1982), slip op. 7-8. One policy of

“ overriding importance” in labor law generally (Hum

phrey v. Moore, 375 U.S. 335, 346 (1946)), and of

special significance under Title VII, is the preservation

of seniority systems and the protection of the rights they

off or demoted have: now been restored to their former positions.

The reinstatement of the employees, however, does not appear to

moot the case.

A case is moot if (1) it can be said with assurance that there

is no reasonable expectation that the enjoined conduct will recur

and (2) interim events have completely and irrevocably eradicated

the effects o f the injunction. County of Los Angeles V. Davis, 440

U.S. 625, 631 (1979). Neither condition appears to be satisfied here.

The City asserts in its: response to the suggestion of mootness (Jt.

Opp. to' Suggestion of Mootness 5) that it “cannot provide assur

ances that further layoffs for fiscal reasons will not be necessitated

during the effective period of the consent decree in this matter.’’ Un

like Boston Firefighters Union V. Boston Chapter, NAACP, No. 82-

185 (May 16, 1983), this case does not involve a state statute: pro

tecting those who were laid off or demoted from future reductions

in force. Thus, it cannot be said with any assurance that the con

troversy giving rise to this litigation will not recur. Nor can it be

said that the reinstatements have completely eradicated the effects

of the layoffs and demotions. According to petitioners, those laid

off lost pay and seniority, and, in some instances, the opportunity

to take promotional exams (Jt. Opp. to Suggestion of Mootnass 5-6

and n .l).

In these circumstances, respondents do not appear to have satis

fied their “heavy” burden ( United States V. W.T. Grant Co., 345

U.S. 629, 632-633 (1953)) of showing that “the issues presented

are no' longer ‘live’ or the parties lack a legally cognizable interest

in the outcome.” Poivell V. McCormack, 395 U.S. 486, 496 (1969).

Rather, the controversy in this case still appears to' be “ definite

and concrete, touching the legal relations of parties having adverse

legal interests.” Aetna Life Insurance Co. V. Haworth, 300 U.S.

227, 240-241 (1937).

9

confer. Trans World Airlines, Inc. V. Hardison, 432 U.S.

63 (1977); 42 U.S.C. 2000e-2(h).

Congress demonstrated particular concern in 1964 that

the proposed Title VII might impair the legitimate in

terests of incumbent employees (see, e.g., 110 Cong. Rec.

486-489 (1964) (remarks of Sen. Hill), and accordingly

conferred immunity under Section 703(h) of Title VII to

bona fide seniority systems. Consistent with this congres

sional intent, this Court has generally resisted efforts by

litigants to modify seniority systems. See, e.g., Team

sters V. United States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977) ; American

Tobacco Co. v. Patterson, 456 U.S. 63 (1982). The only

exception to this rule is the use of constructive seniority

as a proper remedy for identifiable victims of discrimina

tion, because it equitably places them in their rightful

slot within the seniority system and does so without in

any way modifying that system. See Franks V. Bowman

Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747 (1976). This excep

tion is justified because of Congress’s overriding desire to

“make whole” individual victims of discrimination. See

Connecticut V. Teal, 457 U.S. 440 (1982;.

But this case involves both a bona fide seniority sys

tem and claims solely by individuals who have never

shown that they were actual victims of discrimination.

This Court had virtually the same situation before it in

Teamsters V. United States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977), and

held in a slightly different context that no modification of

the employer’s seniority system was justified.

The district court’s order amounts to nothing more than

a retroactive effort to confer constructive seniority rights

identical to those denied the employees in Teamsters who

could not show that they were victims entitled to be

slotted into the seniority system. Time has passed and

the financial condition of the employer has worsened.

But the minorities involved are still non-victims of dis

crimination who can receive relief only at the expense of

“bumping” incumbent white employees. See Patterson v.

10

American Tobacco Co., 535 F.2d 257 (4th Cir. 1976).

Moreover, in order to grant this relief, the district court

must substantially modify the seniority system as it ap

plies to layoffs and demotions and thereby undermine the

City’s legitimate purpose in adopting the system negoti

ated with the union representing its employees. Accord

ingly, the reasoning and holding of Teamsters directly

control this case and forbid the modification of the decree

at issue here.

2. The district court’s order, requiring non-victim mi

norities who are discharged or demoted because of senior

ity to be retained, is contrary to the last sentence of

Section 706(g), 42 U.S.C. 2000e-5(g), which precludes a

district court from ordering reinstatement or promotion

if the reason for an employee’s release or demotion is

something other than race or sex, etc. The last sentence

in Section 706(g), which reflects the statutory intent to

“make whole” actual victims of racial discrimination,

permits employers to make employment decisions on any

basis other than race and thus immunizes the decision of

the City of Memphis to lay off minority employees who

are not victims of discrimination and who have less senior

ity than other employees.

3. By concluding that Title VII permitted the race

conscious order at issue, the courts below have unneces

sarily created a difficult constitutional issue under the

equal protection component of the Due Process Clause of

the Fifth Amendment, regarding the scope of Congress’s

power under Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment to

authorize courts to provide for race conscious reme

dies. Accordingly, the Court should vacate the order as

inconsistent with Title VII in order to avoid the constitu

tional issue that otherwise would exist. See United States

v. Security Industrial Bank, No. 81-184 (Nov. 30, 1982) ;

NLRB v. Catholic Bishop, 440 U.S. 490 (1979).

ARGUMENT

THE DISTRICT COURT’S ORDER EXCEEDED ITS

REMEDIAL AUTHORITY UNDER SECTION 706(g)

OF TITLE VII

The opinion of the court of appeals touches on a variety

of issues relating generally to affirmative action, con

sent decrees and collective bargaining agreements, but

the court’s analysis never reaches the real issue in this

case, viz., whether a district court can modify a consent

decree, which was designed solely to remedy hiring and

promotion discrimination, in order to grant minority in

dividuals, who have made no showing that they were

victims of discrimination, rights that are superior to the

seniority rights of white employees. Thus, regardless of

the validity of the original decree and the relationship in

general between consent decrees and collective bargain

ing agreements— the issues that preoccupied the court of

appeals— this Court’s decisions make clear that a court

cannot, consistent with Title VII of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964, in effect abrogate a seniority system on behalf

of non-victims in order to protect them from layoffs or

demotions that otherwise would occur on the basis of the

last-hired, first-fired rule.112 12

12 A threshold question is whether this ease is controlled by

Title VII principles. The complaint filed by the United States in

1974 was predicated solely on Title VII, but the complaints of the

respondents alleged, in addition to a Title VII violation, that the

employment practices of the Fire Department violated 42 U.S.C.

1981 and 1983 (J.A. 8, 15). The consent agreement, itself, is

plainly limited to Title VII; the City expressly denied any violations

of law, but entered into the agreement “to insure that any dis

advantage to minorities that may have resulted from past hiring

and promotional practices be remedied” (Pet. App. A59-A60; em

phasis supplied). This settlement thus is plainly limited to respond

ents’ Title VII claim that the City’s employment practices have a dis

criminatory effect. See Griggs V. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424

(1971). The City did not concede that it engaged in any purposeful

discrimination, nor has any court made such a finding, which would

be required for this case to be controlled by principles other than

Title VII’s. See Washington V. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976); General

11

12

Although this case was settled, it is clear that for

present purposes the remedial authority of the district

court under 42 U.S.C. 2000e-5(g) is the same as if the

case had gone to a final, litigated judgment.13 Once it

is adjudged that an employer has engaged in an unlawful

employment practice within the meaning of Title VII, a

district court is invested with authority to enjoin the em

ployer from engaging in that practice in the future, and

also is empowered to “ order such affirmative action as

Building Contractors Association V. Pennsylvania, No. 81-280 (June

29, 1982). Accordingly, the propriety of the district court’s remedial

order must be measured by Title VII standards.

13 The opinion of the court of appeals basically ignores Title VII

and focuses exclusively on the authority of a district court to imple

ment a consent decree in light of the parties’ intent and t» adapt

the decree to changed circumstances. The effect of the court’s

reasoning, however, is to grant the district court greater remedial

authority in a, Title VII case concluded by consent decree than the

court would have if the case had been litigated to' final judgment

and a remedial order entered. Obviously, such a result would seri

ously deter employers from entering into consent agreements under

Title VII. This would be in direct contravention of Congress’s

expressed preference for voluntary settlement of employment dis

crimination suits. See W. R. Grace & Co. V. Local 759, No. 81-1314

(May 31, 1983), slip op. 13; Carson V. American Brands, Inc., 450

U.S. 79, 88 n.14 (1981) ; Occidental Life Insurance Co. v. EEOC,

432 U.S. 355, 368 (1977) ; Alexander V. Gardner-Denver Co., 415

U.S. 36, 44 (1974). Moreover, a “ District Court’s authority to adopt

a consent decree comes only from the statute which the decree is

intended to enforce.” System Federation V. Wright, 364 U.S. 642,

651 (1961).

Nor can the expansive relief ordered in this case be justified on

the theory that respondents relied on the consent decree to' assure

their employment, “hav[ing] foregone their right to litigate the

City’s past employment practices and possibly obtain greater relief”

(Pet. App. A37). Respondents already had been granted substantial

affirmative relief in the form of hiring goals that were more than

satisfied by the City. Since respondents were not themselves vic

tims of any discrimination, the district court could not have granted

them any constructive seniority. Teamsters v. United States, supra.

Accordingly, respondents could hardly have obtained any greater

affirmative relief after trial than they received under the settlement.

13

may be appropriate, which may include * * * reinstate

ment, or hiring of employees, * * * or any other equitable

relief as the court deems appropriate.” 42 U.S.C. 2000e-

5 (g ). Although the grant of equitable authority on its

face is broad, it is necessarily constrained by the policies

of the Act, as reflected in its substantive provisions.

Compare H. K. Porter Co. v. NLRB, 397 U.S. 99, 108

(1970). See also Ford Motor Co. v. EEOC, No. 81-

300 (June 28, 1982), slip op. 8; Teamsters v. United

States, 431 U.S. 324, 364 (1977) ; Moragne v. States

Marine Lines, Inc., 398 U.S. 375, 405 (1970).

A. The Order Of The District Court Disregards The

Important Statutory Policy Embodied In Section

703(h), 42 U.S.C. 2000e-2(h), To Protect Seniority

Systems, Ignores The Legitimate Interests Of Incum

bent Employees In Those Systems And Grants Un

warranted Protection To Non-Victims Of Discrimina

tion

What the court of appeals’ discussion of the consent

decrees and collective bargaining agreements completely

ignores is that seniority is not just another term in a

collective bargaining agreement. There is a special statu

tory importance attached to seniority systems and the

rights those systems allocate to employees that bears sig

nificantly on the propriety of a district court’s exercise of

equitable authority. See American Tobacco Co. v. Patter

son, 456 U.S. 63, 75-76 (1982); California Breioers As

sociation v. Bryant, 444 U.S. 598, 606-607 (1980) ;

Humphrey v. Moore, 375 U.S. 335, 346 (1964). This

Court has pointed out that “ seniority systems are af

forded special treatment under Title VII itself.” Trans

World Airlines, Inc. V. Hardison, 432 U.S. 63, 81 (1977).

Section 703(h), 42 U.S.C. 2000e-2(h), by its terms, im

munizes all bona fide seniority systems from challenge

under Title VII, even systems, such as the one in this

case, that have a disproportionate adverse impact on

minorities (Teamsters v. United States, supra), or op

14

erate to perpetuate past employment discrimination

( United Air Lines, Inc. V. Evans, 431 U.S. 553 (1977) ).14

Members of Congress in 1964 were very concerned

about the possible effect the proposed Title VII might

have on the seniority rights of employees. See H.R.

Rep. No. 914, 88th Cong., 1st Sess. 71-72 (1963); 110

Cong. Rec. 486-487 (1964) (remarks of Sen. Hill). Ac

cordingly, Senator Clark, one of the the floor managers

of the bill, submitted a Justice Department memorandum

stating that the proposed Title VII would not affect exist

ing seniority rights. 110 Cong. Rec. 7207 (1964) ; id. at

7212-7215; id. 7216-7217 (remarks of Sen. Clark).

During the Senate debates, Section 703(h) was in

cluded in the substitute bill that eventually was adopted.

The provision was adopted to clarify the Act’s “present

intent and effect” with regard to seniority. 110 Cong.

Rec. 12723 (1964) (remarks of Sen. Humphrey); id. at

12818-12819 (remarks of Sen. Dirksen).15 Congress thus

intended generally to accord special status to seniority

systems and the stability that they provide to labor re

lations and specifically expressed concern that Title VII

not operate to modify the last-hired, first-fired principle

that lies at the heart of most seniority systems. Ac

cordingly, Title VII remedies must be designed to pre

serve the fundamentals of bona fide seniority systems.

Compare American Tobacco Co. v. Patterson, supra;

United Air Lines, Inc. v. Evans, 431 U.S. 553, 559

(1977); Teamsters v. United States, supra; California

14 Section 703(h) of Title VII, 42 U.S.C. 2000e-2(h), provides, in

pertinent part:

Notwithstanding any other provision of this subchapter, it

shall not be an unlawful employment practice for an employer

to apply different standards of compensation, or different

terms, conditions, or privileges o f employment pursuant to' a

bona fide seniority * * * system * * * provided that such dif

ferences are not the result of an intention to discriminate be

cause of race * * *.

15 Congress made no change in Section 703(h), when it revised

Title VII in 1972. See Teamsters V. United States, supra, 431 U.S.

at 354 n.39.

15

Brewers Association v. Bryant, 444 U.S. 598 (1980),

with Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747

(1976).

Under this Court’s decisions, the only accommodation

that a bona fide seniority system must make under Title

VII is to allow actual victims of discrimination to be

slotted into their rightful place in the system. See, e.g.,

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., supra. Franks

involved a discrimination claim by a class of black non

employee applicants who had unsuccessfully sought em

ployment as over-the-road truck drivers. The district

court found that the employer had engaged in a pattern

of racial discrimination in hiring, transfer and discharge

of employees. The district court ordered the employer to

give priority consideration to class members for over-

the road jobs, but declined to award back pay or con

structive seniority retroactive to the date of the individ

ual’s application. The court of appeals reversed the dis

trict court’s ruling on hack pay, but affirmed its refusal to

award retroactive seniority.

This Court held that for actual victims of unlawful

discrimination constructive seniority back to the date of

the discriminatory act was an appropriate remedy in

order to restore those victims to their “rightful place,”

that is, restore them “to a position where they would have

been were it not for the unlawful discrimination.” 424

U.S. at 764, quoting 118 Cong. Ree. 7168 (1972). See also

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 421

(1975).

The Court’s remedial holding granting make-whole re

lief to individual victims reflects Congress’s dominant

concern in Title VII for protecting the individual. Un

lawful employment practices are defined by an employer’s

decision to hire or fire “any individual, or otherwise to dis

criminate against any individual * * * [or to] deprive or

tend to deprive any individual of employment oppor

tunities” because of the individual’s race, etc. 42 U.S.C.

2000e-2 (a). “ The principal focus of the statute is the

protection of the individual employee * * *. Indeed, the

16

entire statute and its legislative history are replete with

references to protection for the individual employee

* * *.” Connecticut v. Teal, 457 U.S. 440, 453-454

(1982); see also Los Angeles Department of Water &

Power v. Manhart, 435 U.S. 702, 709 (1978) ; Arizona

Governing Committee V. Norris, No. 82-52 (July 6, 1983),

slip op. 9; pages 17-21, 26-29, infra.

Thus, where the dominant concern of Congress— mak

ing individual victims whole—has competed with Con

gress’s concomitant intention to protect seniority systems

and the rights they accord to incumbent employees, this

Court has very carefully accommodated both interests.

Significantly, the constructive seniority rights awarded in

Franks were not judicially invented rights, but only the

rights defined by the existing seniority system itself, once

the “ rightful place” in that system of each identifiable

victim of discrimination was determined. The seniority

right of incumbent employees would also continue to be

defined by that system, even though the “ rightful place”

in that system of some incumbents would be adjusted to

accommodate the rights of individuals who would have

been senior to them but for the employer’s unlawful dis

criminatory acts. See 424 U.S. at 774-779. Thus, the

relief prescribed in Franks fundamentally preserves

rather than abrogates rights under bona fide seniority

systems, while extending those rights to identifiable

victims of discrimination in order to make them whole.

The basic statutory preservation of bona fide seniority

systems was reasserted by the Court the next year in

Teamsters V, United States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977). In

Teamsters, the defendant trucking company •was found to

have engaged in an unlawful pattern or practice of con

fining blacks and Hispanics to lower paying, less desirable

jobs, and excluding them from positions as over-the-

road (“ OTR” ) truck drivers. The seniority system in the

employer’s collective-bargaining agreement provided that

an incumbent employee who transferred to an OTR posi

tion was required to forfeit the competitive seniority he

had accumulated in his previous position (company sen

iority) and to start at the bottom of the OTR driver’s

seniority list.

After affirming the district court’s finding of liability

under Title VII, the court of appeals held that all black

and Hispanic incumbent employees—including those who

had never applied for OTR positions— were entitled to bid

for future OTR jobs on the basis of their accumulated

company seniority. The appeals court further held that

each class member filling such a job was entitled to an

award of retroactive seniority on the OTR driver’s sen

iority list dating back to the class member’s “ qualifica

tion date”— the date when (1) an OTR driver position

was vacant and (2) the class member met or could have

met the job’s qualifications.

This Court first reversed the holding that the defend

ant’s seniority system was itself subject to attack as

perpetuating the past effects of discrimination. Although

the system appeared to violate the rationale in Griggs v.

Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971), the Court held that

Congress did not “ outlaw the use of existing seniority

lists and thereby destroy or water down the vested sen

iority rights of employees * * *.” 431 U.S. at 352-353.

The Court then considered what remedy was appro

priate for the other discriminatory employment practices

that had been proved. This Court rejected the defend

ant’s argument that only individuals who had actually

applied for OTR positions could obtain relief under Sec

tion 706(g). Instead, the Court held that relief in the

form of constructive seniority was available to those

who could satisfy the burden of proving that they were

deterred from applying for that position because of the

employer’s discriminatory practices and that they were

qualified for the job. 431 U.S. at 372. This latter class

of plaintiffs, like those who were actually precluded from

obtaining the OTR jobs, could show when they presumably

would have been employed, but for the discrimination,

and thus relief to them would not require modification of

the seniority system itself, but merely “rightful place”

fitting of individuals into that system. 431 U.S. at 358.

17

18

As for those who could not make such a showing, the

necessary result is that they were not entitled to any

relief in the form of constructive seniority.

Teamsters establishes that Title VII remedies must

preserve the seniority rights protected in Section 703(h).

Preservation of those rights serves two important con

cerns : protecting the stability of labor relations by main

taining the seniority system and being fair to innocent

incumbent employees.1,6 With regard to the latter concern,

this Court recently emphasized that, in crafting equitable

relief under Title VII, courts must consider the legit

imate interests of “ innocent third parties.” Ford Motor

Co. V. EEOC, supra, slip op. 20. See also Arizona Gov

erning Committee v. Norris, supra, slip op. 5 (O’Connor,

J., concurring). Indeed, even in a case (unlike this

one) in which specified victims of unlawful employment

discrimination have been identified, a court, in determin

ing their rightful place, is “ faced with the delicate task of

adjusting the remedial interests of discriminatees and

the legitimate expectations of other employees innocent of

any wrongdoing.” Teamsters v. United States, supra,

431 U.S. at 372.16 17

16 Lower courts, have uniformly held that the relief for actual

discriminatees doe'S not extend to bumping employees previously

occupying jobs; victims must wait for vacancies to' occur. See,

e.g., Patterson V. American Tobacco Co., 535 F.2d 257, 267 (4th

Cir. 1976) ; Local 189, United Papermakers and Paperworkers V.

United States, 416 F.2d 980, 988 (5th Cir. 1969). See also Airline

Stewards <£ Stewardesses Association v. American Airlines, 573

F.2d 960, 964 (7th Cir.), cert, denied, 439 U.S. 876 (1978). This

understanding of the limits of Section 706(g) with regard to' actual

victims may well have been ratified by Congress in 1972, since it

was aware of the United Papermakers decision and nothing indi

cates that the amendment to' Section 706(g) was an attempt to alter

that interpretation.. See Subconam. on Labor of the Senate Comm,

on Labor and Public Welfare, 92d Cong., 2d Sess., Legislative

History of the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972, at 1844

(Comm. Print 1972) (hereinafter cited as 1972 Legislative History).

17 The court of appeals incorrectly relied upon the Seventh Cir

cuit’s decision in Airline Stewards and Stewardesses Association V.

American Airlines, supra, as showing how consent decrees can

19

In Ford Motor Co. v. EEOC, supra, this Court relied

upon both the basic congressional intent to protect senior

ity and the importance of fairness to incumbent employees

in deciding that an employer charged with hiring dis

crimination under Title VII can toll the continuing ac

crual of back pay liability under Section 706(g) by un

conditionally offering the claimant the job allegedly denied

him for impermissible reasons. The Court expressly re

jected the argument that the employer must also offer

seniority retroactive to the date of the alleged discrimina

tion, for such a rule would “encourage [] job offers that

compel innocent workers to sacrifice their seniority to a

person who has only claimed, but not yet proven, un

lawful discrimination.” Slip op. 21 (emphasis added).

Foreseeing the possibility that layoffs could occur before

the reinstated (or newly hired) claimant’s Title VII suit

was decided, the court reasoned that (ibid.)

an employer may have to furlough an innocent

worker indefinitely while retaining a claimant who

was given retroactive seniority. If the claimant

modify collective bargaining agreements in order to further the

statutory policy favoring settlements of Title VII cases. The Stew

ardesses case, correctly understood, is contrary to- the decision her

low and illustrates how the relevant interests should be accom

modated under Title VII. In Stewardesses, it was undisputed that

each member of the plaintiff class had been a victim of the defend

ant’s employment discrimination, but there was a dispute as to

whether each member had preserved her right to sue. The defendant

settled the case, and the intervening union sought to challenge

the settlement.

In upholding the settlement, the court of appeals noted that each

member of the class was a victim and that, although they all would

receive seniority dating to the time of their wrongful discharge,

they would not be hired unless there were an opening and they

would not be permitted to bump incumbent employees from a partic

ular base, even though their constructive seniority might otherwise

have entitled them to do so. This is precisely the type of careful

accommodating of the rights of actual victims of discrimination

and innocent incumbent employees that this Court’s decisions re

quire, and stands in stark contrast to the decision below which

forced incumbent employees to be laid off SO' that non-victim

minorities could keep their jobs.

2 0

subsequently fails to prove unlawful discrimination,

the worker unfairly relegated to the unemployment

lines has no redress for the wrong done him. We

do not believe that “ ‘the large objectives’ ” of Title

VII * * * require innocent employees to carry such

a heavy burden.

What emerges from this Court’s decisions is the firm

rule that a district court in a Title VII case may not

modify a bona fide seniority system; it can only slot indi

viduals into their rightful place within that system. In

dividuals, such as those involved in this case, who are

only beneficiaries of affirmative action and not victims of

employment discrimination entitled to rightful place re

lief, have no basis for claiming any seniority in addition

to what they have actually accrued on the job. Thus,

when the initial hiring order was issued in 1974 and

again in 1980, the district court would have been wholly

without authority to slot new applicants in place of in

cumbents (see note 16, swpra) or to award non-victims

of discrimination constructive seniority when hired. The

district court’s order insulating a certain percentage of

minority employees from dismissal under the race neutral

seniority system adopted by the City was, however, tanta

mount to an award of constructive seniority that placed

its beneficiaries in a position superior to that of incum

bent non-minority employees.18 Since the order concededly

18 It is of no significance that the award of constructive seniority

here was only, for the limited purpose of determining who would

be laid off or demoted. Under the City’s bona fide seniority system,

that important question was to be determined on the basis of

seniority.

Nor can the order be justified by the hyperbole of the: courts

below that the proposed layoffs would undo all the good that the

previous orders had accomplished. First, the percentage of minori

ties in the Fire Department is still significantly greater than it was

when this litigation began and thus, the post-layoff Department is

significantly improved in racial balance over the prelitigation situ

ation. Second, although layoffs are always traumatic to the individ

ual, they do not normally last forever. The laid off minority em

ployees are at the top of the list to be rehired or promoted and,

21

embraced persons who were not victims of the defendants’

unlawful employment discrimination, the district court’s

award of retroactive seniority was indistinguishable-—save

in its timing— from the award condemned in Teamsters.w

In the instant case, innocent firefighters were required

to sacrifice not only their seniority, but also their jobs, to

persons who have never claimed to be victims of unlawful

discrimination. As a result of the district court’s decree,

white firefighters with more years of service than black

employees were furloughed or demoted, thus creating a

new class of victims, who were innocent of any wrong

doing, but were deprived of their rights under a valid

without the district court’s modification, when the financial crisis

of the City is over, if it is not already, and fire personnel are hired

or repromoted, minorities will continue back on the track set by the

1980 order. The effect of the layoff is delay in achieving the order’s

goal of a rough racial balance in employment at all levels, but delay

is inherent in that process, given the legitimate interests of incum

bents, and does not justify extraordinary relief.

w Nor is a contrary result justified by the court of appeals’ asser

tion that allowing layoffs would undermine: the purpose of the- 1980

decree (Pet. App. A37). There has been no new violation o f the Act

that would require a modification of the decree and accordingly

the issue is simply whether the district court could have modified

the seniority system when it initially entered its order in 1980. If

the City of Memphis had been faced with this budgetary crisis in

1980 when the original affirmative action order was imposed, no

one would have suggested that the remedial order was undermined

by the temporary failure of the City to integrate its. work force.

Certainly, the district court would have lacked authority either to

order the City to hire additional employees or to require the City

to bump incumbent white employees to make room for minority

hires. See cases cited note 16, supra. The order in this case

does no more than retroactively accomplish what the court could

not have- done directly in 1980 if the economic problems had existed

then; it requires the City essentially to bump incumbent whites.

This result is directly contrary to this Court’s admonition that

equity under Title YII should not permit “ ‘different results for

breaches of duty in situations that cannot be differentiated in

policy.’ ” Ford Motor Co. v. EEOC, supra, slip op. 8 (citation

omitted).

22

seniority system.20 This was not a permissible exercise

of remedial authority under Title VII. That remedial

authority is limited to the effectuation of the policies of

the Act; one of the Act’s firmly established policies is the

preservation of bona fide seniority systems. No court has

found any discriminatory purpose underlying the senior

ity system in this case 21 and accordingly the district court

bo The1 court of appeals reasoned (Pet. App. A32) that modifica

tion of the consent decree could be justified as an interpretation

of the consent decree as a contractual obligation. Aside from the

obvious point that the parties made no provision for layoffs and

thus the decree cannot fairly be construed to require modification

of the layoff process (Pet. App. A46; Martin, J., dissenting), it is

clear that the City could not unilaterally contract away the incum

bent employees’ seniority rights that are in fact protected by Title

VII. See W.R. Grace & Co, V. Local 759, No. 81-1314 (May 31,

1983), slip op. 14.

Nor could such an agreement be approved under United Steelwork

ers V. Weber, 443 U.S. 193 (1979). Unlike the private voluntary craft

training program in that case, the court’s layoff order led directly

to the discharge of senior white employees, solely in order to main

tain existing racial percentages. Even in interpreting Title- VIPs

prohibitions in a context not involving state action, Weber dis

approved actions which “ unnecessarily trammel the interests of the

white employees.” 443 U.S. at 208. In contrast to this case, two of

the critical facts leading to the conclusion that the training pro

gram in Weber did not violate Title VII were that the program

did not require thei discharge of white workers and their replace

ment with new black hires and was not intended to maintain

racial balance. What is more important, the defendant in this case

is a municipality and its conduct constitutes state action. Accord

ingly, the court of appeals’ “contract” theory also implicates a

serious equal protection issue, which that court completely ignored.

Since the City plainly did not enter into a contract modifying

seniority rights on, the- basis of race, however, there is no need for

the Court to- consider the constitutional implications of such a

contract.

21 The court of appeals at one point seems to- indicate- that the

City selected job classifications for layoff “where- minorities had

recently made the most, gains under the affirmative- action, pro

visions” (Pet. App. A37). No similar finding was made by the

district court, and the Mayor of the City testified that jobs in the

Fire Department were chosen because a study revealed that the

23

was without authority to reconstruct it.22

B. The Limitation On The Court’s Remedial Authority

Contained In The Last Sentence Of Section 708(g)

Confirms That Congress Did Not Intend To Grant

Constructive Seniority In The Circumstances Of This

Case

Our argument that the policies of Title VII make plain

that bona fide seniority systems ought not to be modified

to grant non-victim beneficiaries of affirmative action

additional protection from layoffs is confirmed by the

limitation on the powers of a court of equity in Title VII

cases contained in the last sentence of Section 706(g).

That sentence reads in pertinent part:

No order of the court shall require the * * * rein

statement, or promotion of an individual as an em

ployee * * * if such individual * * * was suspended

City’s budget for the Fire Department was substantially higher

than the national average and thus cute could be made there with

out eliminating necessary services. (J.A. 36-37).

Obviously, if the City had selectively chosen layoffs on the basis

of which jobs were filled by more blacks, this would be an inde

pendent basis for challenging the City’s action, but the remedy

for such discrimination would not be to- require a modification in

the City’s bona fide seniority system.

33 The decision of the district court cannot be sustained as a

proper exercise of “ discretion in protecting the status quo in the

Fire Department” (Pet. App. A46) (Martin, J., concurring and dis

senting) . While it is true that the entry of a preliminary injunction

by a district court generally is reviewable on an abuse of discretion

standard, “ [ i ] f the [reviewing] court has a view as to the applicable

legal principle that is different from that premised by the trial

judge, it has, a duty to apply the principle which it believes proper

and sound.” Delaware & H. Ry. V. United Transportation Union, 450

F.2d 603, 620 (D.C. Cir.) (Leventhal, J.), cert, denied, 403 U.S. 911

(1971). See also Withrow v. Larkin, 421 U.S. 35, 55 (1975). The

preservation of the status quo cannot be justified at the expense of

wrongfully depriving the enjoined party and third parties of sub

stantial rights. 450 F.2d at 621; O’Connor V. Board of Education,

645 F.2d 578, 582-583 (7th Cir.), cert, denied, 454 U.S. 1084 (1981) ;

Punnett V. Carter, 621 F.2d 578, 587 (3d Cir. 1980).

24

or discharged for any reason other than discrimina

tion on account of race, color, religion, sex, or na

tional origin * * *.

Section 706(g) by its terms thus precludes the kind of

individual redress granted to these minority employees

who have suffered no discrimination.28

This conclusion is also required by the remedial pur

poses of Title VII embodied in Section 706(g). As this

Court has recognized, “ [t]he scope of a district court’s

remedial powers under Title VII is determined by the

purposes of the Act.” Teamsters V. United States, supra,

431 U.S. at 364. The central remedial purposes of Title

VII are, as this Court has often observed, “to end dis

crimination * * * [and] to compensate the victims for

their injuries.” Ford Motor Co. v. EEOC, supra, slip op.

11; see, e.g., Teamsters v. United States, supra, 431 U.S.

364; Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, supra, 422 U.S, at

418. Section 706(g) thus requires a court “ to fashion

such relief as the particular circumstances of a case may

require to effect restitution, making whole insofar as

possible the victims of racial discrimination in hiring.”

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., swpra, 424 U.S.

at 764 (footnote omitted) ; accord, Teamsters v. United

States, supra, 431 U.S. at 364.

The district court’s decree ordered the City to imple

ment layoffs in order to maintain existing levels of black

employees. In other words, the decree required the City

to lay off employees in accordance with racial quotas, and

did so without regard to whether the individuals retained

had been the actual victims of the City’s employment dis

crimination. This remedy, which inevitably provides em

ployment preferences to individuals who were not “ sus

pended or discharged” by the employer in violation of

Title VII, would thus appear to be the archetypal form 23

23 The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission disagrees with

this interpretation of Section 706(g) and believes that its adoption

might call into- question numerous extant consent decrees and con

ciliation agreements to which the EEOC is party.

25

of relief that Congress determined should not be used to

“ remedy” such violations of the Act. The statute’s lan

guage on this point is further supported by its legislative

history.24 25 * *

Representative Celler, floor manager of the House bill

in 1964 and a principal draftsman of Section 706(g) (see

110 Cong. Rec. 2567 (1964) (remarks of Rep. Celler)),

expressly noted that a court order could be entered only

on proof “ that the particular employer involved had in

fact, discriminated against one or more of his employees

because of race,” emphasizing that “ [e]ven then, the

court could not order that any preference be given to any

particular race * * *, but would be limited to ordering an

end to discrimination.” Id. at 1518. Representative Cel-

ler’s understanding of Title VII was repeated by other

supporters during the House debate:2®

Supporters of Title VII in the Senate, following the

lead of Senator Humphrey, the Democratic floor manager

of the bill (110 Cong. Rec. at 5428 (1964)), took a sim

ilar view of the remedial authority of the courts under

Section 706(g). In an interpretative memorandum often

cited by this Court as an “authoritative indicator” of the

meaning of Title VII (e.g., American Tobacco Co. v. Pat

terson, supra, 456 U.S. at 73), Senators Clark and Case,

the bipartisan floor “ captains” responsible for explaining

Title VII, provided a detailed description of the intended

24 For a fuller description of the legislative history, see Com

ment, Preferential Relief Under Title VII, 65 Va. L. Rev. 729

(1979). See also Brief Amicus Curiae for the AFL-CIO at pages

18-25 and la-8a.

25 See 110 Cong. Rec. 1540 (Rep. Lindsay); id. at 1600 (Rep.

Minish). Similarly, an interpretative memorandum prepared by

the Republican Members of the House Judiciary Committee de

fined the scope of permissible judicial remedies under Title VII

thusly: “ [A] Federal court may enjoin an employer * * * from

practicing further discrimination and may order the hiring or

reinstatement of an employee * * *. But, [Tjitle VII does not

permit the ordering of racial quotas in businesses or unions * * *.”

(Id. at 6566 (emphasis added)).

meaning of Section 706(g). Noting that “ the court could

order appropriate affirmative relief,” Senators Clark and

Case stressed:

No court order can require * * * reinstatement * * *

or payment of back pay for anyone who was not

discriminated against in violation of this title. This

is stated expressly in the last sentence of Section

[706(g)] which makes clear what is implicit

throughout the whole title; that employers may hire

and fire, promote and refuse to promote for any

reason, good or bad, provided only that individuals

may not be discriminated against because of race,

color, religion, sex, or national origin. [110 Cong.

Rec. at 7214. See id. at 6549 (Senator Humphrey).]

Moreover, nothing in the 1964 legislative debates so

much as hints at support for the remedy adopted by the

district court here. To the contrary, every Representa

tive and every Senator to address the issue decried the

use of such remedies. See 110 Cong. Rec. 6549 (remarks

of Sen. Humphrey) ; id. at 6563 (remarks of Sen. Ku-

chel), 7207 (remarks of Sen. Clark).2,0

Congress’s dominant concern with granting victim-

specific, make-whole relief was not modified when Con

gress amended Title VII in 1972. The only arguably

relevant change of Section 706(g) was the addition of 28 * * * * * * * *

28 To dispel all doubt as to the intended reach of Section 706(g),

Senator Humphrey expressly addressed the claims of opponents

regarding quota remedies as follows (110 Cong. Rec. 6549) : “ Con

trary to the allegations o f some opponents of this title, there1 is

nothing in it that will give any power to the Commission or to any

court to require * * * firing * * * of employees in order to meet a

racial ‘quota’ or to' achieve a certain racial balance.” See also id. at

6563 (remarks of Sen. Kuchel); id. at 7207 (remarks of Sen. Clark).

Moreover, throughout the Senate' debate, the principal Senate spon

sors prepared and delivered a daily Bipartisan Civil Rights Newslet

ter to1 supporters of the bill. The issue of the Newsletter published

two days after the opponents’ filibuster had begun, declared: “Under

title VII, not even a court, much less the Commission, could order

racial quotas or * * * payment of back pay for anyone who is not

discriminated against in violation of this title.” Id. at 14465 (em

phasis added).

2 6

27

language making clear that discriminatees are entitled

not only to the specific types of relief expressly mentioned

in the section, but also to “any other equitable relief as

the court deems appropriate.” 27

That this language was not added to the first sentence

of Section 706(g) for the purpose of expanding judicial

remedial authority beyond traditional limits is made clear

in the Section-by-Section Analysis of the conference bill.28 * 38

27 The language added in 1972 had its origin in an amendment

introduced by Senator Dominick, who opposed a provision in the

Labor Committee bill to confer “cease and desist” authority on the

EEOC ; the committee bill proposed to make no change in either

Section 70S or Section 706(g). Dominick’s filibuster of the com

mittee bill ended with adoption of his amendment, which denied the

EEOC independent enforcement authority, but granted it power

to institute lawsuits in federal court. The purpose o f the language

added to the first sentence of Section 706(g) was not explained,

or even discussed, by Senator Dominick or anyone else during the

debate.

38 The House of Representatives legislated in 1972 on the under

standing that Title VII did not, and as amended would not, au

thorize judicial impostion. of quota remedies. Although it is not

at all clear precisely what any individual member of Congress meant

when referring to “quotas,” either in 1964 or 1972, it seems plain

that the definition must encompass the type of strict numerical

guarantee against layoffs at issue in this case. Accordingly, there

is no occasion to' consider here whether these legislative statements

would apply to any situation except the classic, fixed numerical

quota remedy in the layoff context.

The 1972 amendments began in the House, where Representative

Hawkins introduced a bill designed, among other things, to give

the EEOC “cease and desist” powers and to transfer the adminis

tration of Executive Order No. 11246 from the Labor Department's

Office of Federal Contract Compliance (OFCC) to the EEOC. Be

cause the OFCC had imposed quotas in its enforcement of E.O.

11246, many members of Congress feared that the bill would confer

on the EEOC authority to order employment quotas.

Before1 debate1 commenced, Representative Dent, the bill’s floor

manager, proposed an amendment that “would forbid the EEOC

from imposing any quotas or preferential treatment of any employees

in its administration of the Federal contract-compliance program.”

1972 Legislative History, supra, note 16, at 190. The amendment did

not address the remedial power of courts under Title VII because,

That Analysis explained that “ the scope of relief under

[Section 706(g)] is intended to make the victims of un

lawful discrimination whole, * * * [which] requires that

persons aggrieved by the consequences and effects of the

unlawful employment practice be, so far as possible, re

stored to a position where they would have been were it

not for the unlawful discrimination.” (Emphasis added.)

118 Cong. Rec. 7168 (Senate); id. at 7565 (House).39

Compare Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., supra,

424 U.S. at 764. 29 *

28

according to Representative Dent, “ [s]uch a prohibition against the

imposition of quotas or preferential treatment already applies to' ac

tions brought under Title VII.” Ibid. See also id. at 204; id. at 208-

209 (remarks of Rep. Hawkins). The House ultimately passed a sub

stitute bill that left administration of Executive Order No. 11246

with the OFCC, and the Dent amendment never came a vote. The

House debate reflects, however, broad agreement that; Title VII does

not and should not permit courts to order “quota” remedies.

It is also noteworthy that the 1972 Congress refused to follow

the Senate’s proposed amendment to delete the final sentence from

Section 706(g). (S. 2515, 92d Cong., 2d Sess. (1972); 1972 Legisla

tive History, supra, note 16, at 1783). Instead, it ultimately adopted

the House bill (H.R. 1746, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. (1972)), which left

the 1964 provision largely unchanged, except for the addition of a

provision limiting back pay awards. See 1972 Legislative History at

331-332. Thus the bill that ultimately emerged from the House-

Senate conference and became law contained the original final

sentence of Section 706 (g ). S. Conf. Rep. No. 92-681, 92d Cong., 2d

Sess. 5-6, 18-19 (1972) ; H.R. Conf. Rep. No. 92-899, 92d Cong., 2d

Sess, 5-6, 18-19 (1972).

29 Some courts construing Section 706(g) have mistakenly at

tached interpretative significance to Senator Ervin’s unsuccessful at

tempt to amend Title VII in 1972. See United States V. Int’l Union

of Elevator Constructors, 538 F.2d 1012, 1019-1020 (3d Cir. 1976).

Those amendments, however, did not seek to alter Section 706(g).

Indeed, it is clear from the language of the amendments (118

Cong. Rec. 1662, 4917) and from their sponsor’ s explanations (id.

at 1663-1664, 4917-4918) that neither amendment was concerned

directly with the remedial authority of courts. To the contrary,

the amendments would merely havei extended to all federal Executive

agencies, particularly the Office of Federal Contract Compliance,