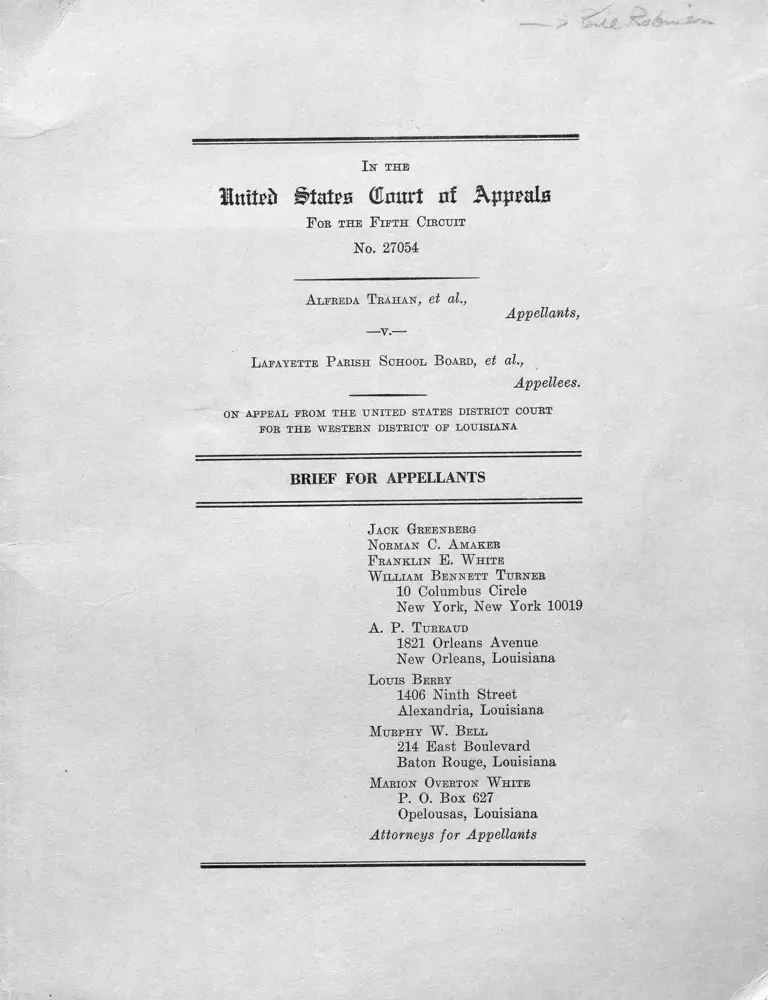

Trahan v. Lafayette Parish School Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Trahan v. Lafayette Parish School Brief for Appellants, 1969. 94b3ca77-c69a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/bc4c2160-b99b-4e71-a2e8-8de1bd3bb5de/trahan-v-lafayette-parish-school-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

In thb

In \t& States QJmtrt of Appeals

F ob t h e F if t h C ib cu it

No. 27054

A lfreda T r a h a n , et al.,

—v.—

Appellants,

L afayette P abish S chool B oard, et al.,

Appellees.

on appeal from t h e u n ited states district court

FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

J ack G reenberg

N orm an C. A m a k e r

F r a n k l in E. W h ite

W il l ia m B e n n e tt T u rn er

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A. P. T ureaud

1821 Orleans Avenue

New Orleans, Louisiana

Louis B erry

1406 Ninth Street

Alexandria, Louisiana

M u r p h y W . B ell

214 East Boulevard

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

M arion Overton W h it e

P. O. Box 627

Opelousas, Louisiana

Attorneys for Appellants

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES i

ISSUES PRESENTED 1

STATEMENT 2

ARGUMENT 3

I. Introduction 3

II. The Affirmative Duty of the School

Boards to Bring About Integrated

Unitary School Systems Requires the

Abandonment of Free Choice Plans

and the Adoption of Alternative

Plans Which Will Promptly Eliminate

Racially Identifiable Schools 5

III. Specific Target Dates and Accom

plishments for Faculty Integration

must be Required to Assure the

Elimination of Racially Identifi

able Schools 17

CONCLUSION 22

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

Paqe

Adams v. Mathews, 403 F.2d 181, 188 (5th

Cir. 1968) 10,17,20

Banks v. St. James Parish School Board,

No. 16173 (E.D. La. Dec. 10, 1968) 12

Board of Public Instruction of Duval County,

Fla. v. Braxton, 402 F.2d 900 (5th Cir.

1968) 16

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483

(1954) 4

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294

(1955) 4,13-14

Dowell v. School Board of Oklahoma City

Public Schools, 244 F.Supp. 971, aff'd

375 F.2d 158, cert, denied 387 U.S. 931

(1967) 22

Dunn v. St. Charles Parish School Board,

No. 67147 (E.D. La. Dec. 10, 1968) 12

Graves v. Walton County Board of Education,

403 F.2d 189 (5th Cir. 1968) 10

Green v. County School Board of New Kent

County, Virginia, 391 U.S. 430, 441-2

(1968) 8,9,12,14,17,20

Jones v. Caddo Parish School Board, 392

F.2d 723 (5th Cir. 1968) 19

Kelley v. The Altheimer, Arkansas Public

School District, No. 22, 378 F.2d 483,

490 (8th Cir. 1967) 11

i

Cases (cont.)

Page

Kemp v. Beasley, 389 F.2d 178, 183 (8th

Cir. 1968) 11

Kier v. County School Board of Augusta

County, 249 F.Supp. 239 (W.D. Va. 1966) 22

Monroe v. Board of Commissioners of Jackson,

Tennessee, 391 U.S. 450 (1968) 9

Montgomery County Board of Education v.

Carr, 400 F .2d 1 (5th Cir. 1968), reargu

ment en banc denied 402 F .2d 782 (5th

(Cir. 1968) 20,21

Moore v. Tangipahoa Parish School Board, No.

15556 (E.D . La. Nov. 27, 1968) 12

Moses v. Washington Parish School Board, 276

F.Supp. 834, 838, 851 (E.D. La. 1967) 7

Moses v. Washington Parish School Board, No.

15973 (E.D. La. Jan. 14, 1969) 13

Redman v. Terrebonne Parish School Board,

No. 15663 (E.D. La. Dec. 5, 1968) 12

United States v. Board of Education of the

City of Bessemer, 396 F.2d 44 (5th Cir.

1968) 15,18,19

United States v. Greenwood Municipal Separate

School District, No. 25714 (5th Cir. Feb.

4, 1969) 11,13,15,16,18,20

United States v. Jefferson County Board of

Education, 372 F.2d 836, aff1d with modi-

fications on rehearinq en banc, 380 F.2d

385, cert, denied sub. nom. Caddo Parish

School Board v. United States, 389 U.S.

840 (1967) 4,6,15,18

n

Cases (cont.)

United States v. School District 151 of

Cook County, Illinois, 286 F.Supp. 786,

798 (N.D. 111. 1968), aff'd F.2d

___ (7th Cir. 1968)

Other Authorities

Meador, The Constitution and the Assignment

of Pupils to Public Schools, 45 Va.L.Rev.

517 (1959)

iii

Page

22

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

ALFREDA TRAHAN, et al.,

Appellants,

vs. No. 27054

LAFAYETTE PARISH SCHOOL BOARD, et al.,

Appellees.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Western District of Louisiana

ISSUES PRESENTED

1. Whether the Court below erred in approving the

continued use of free choice plans, without requiring the school

boards to submit alternative plans eliminating racially ident

ifiable schools, where free choice has permitted the school

boards still to maintain all-Negro schools, where only token

numbers of Negro students attend previously all-white schools

and where faculty integration is minimal.

2. Whether the court below erred in failing to re

quire specific target dates and accomplishments for faculty

desegregation where only token numbers of teachers have been

assigned across racial lines and where the pattern of teacher

assignment in each school is still identifiable as tailored

for a heavy concentration of either Negro or white students.

STATEMENT

The fifteen school desegregation cases consolidated

under the caption of this case all arise from the Western

District of Louisiana. The appellant Negro school children

seek the elimination of the racially dual school systems main

tained by the appellee school boards.

These cases bear many "service stripes" in the

courts, and some of them have, at various times, been before

this Court. The present appeal is from a decision, filed

November 14, 1968, of the three judges of the Western Dis

trict sitting en banc. The extraordinary en banc decision

of the court below was rendered after a consolidated hearing

of thirty Western District school cases held on November 12,

1968. The hearing was held pursuant to the direction of

Chief Judge Ben C. Dawkins, Jr., dated August 7, 1968, that

"the questions of zoning of attendance districts and reassign

ing faculties and staffs" would be considered by all three

District Judges.

The court below conceived that the issue before it

was whether free choice plans "constitute adequate compliance

with the Board’s responsibility to achieve a system of deter

mining admission to the public schools on a non-racial basis"

-2-

(opinion, p.l). Having so defined the issue, the court, with

out considering any alternatives to freedom of choice plans,

broadly approved their continuation in all fifteen cases.

The court also failed to specify target dates and accomplish

ments for faculty integration.

Appellants moved in this Court to consolidate

these fifteen cases, to expedite the appeals and for hear

ing by the full Court sitting en banc. The motion for en

banc hearing was denied on January 9, 1969. The motions to

consolidate and expedite were granted on January 17, 1969.

The same disposition was made of similar motions by the

United States and the other private appellants in the other

Western District cases heard with the instant cases below.

ARGUMENT

I. Introduction

The painful history of school desegregation in

this Circuit is well known to the Court and need not be re

peated here. Suffice it to say that none of the appellee

school boards made any step toward dismantling their segre

gated systems for more than a decade after the Supreme Court

declared that it was unconstitutional to maintain "separate

-3-

but equal" schools for Negro and white children. Brown v.

Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) (Brown I). They

simply ignored the Court's decision in Brown II directing

them to effectuate the transition to a non-racial system

with all deliberate speed. 349 U.S. 294 (1955).

The school boards did nothing until they were sued.

Not until the school year 1965-66 was pupil integration be

gun. In that year ten of the fifteen school systems involved

here began to operate under some form of freedom of choice;

the other five (Vermilion, Madison, Natchitoches, Jefferson

Davis and Caddo Parishes) began in 1966-67. All of the

school boards have now operated for two years under the uni

form decree mandated by this Court in United States v. Jeffer

son County Board of Education, 372 F.2d 836, aff'd with modi

fications on rehearing en banc, 380 F.2d 385, cert, denied

sub, nom. Caddo Parish School Board v. United States, 389 U.S.

840 (1967).

Despite four years' experience with self-assignment

by pupils in most of the cases and three years in the others,

every school board is still maintaining a racially dual sys

tem. The Court is respectfully referred to Appendix A to

-4-

this brief for a comprehensive review of the results of free

dom of choice in each parish. The contents of the Appendix

are tabulated from the school opening reports filed by each

board pursuant to the Jefferson decree.

There are still all-Negro schools in every parish.

Only handfuls of Negro students have assigned themselves to

"white" schools and, except in Bossier and Caddo Parishes,

not a single white child has chosen to go to a "Negro" school.

Faculty desegregation is minimal and in every parish and even

every school the pattern of teacher assignment is readily

identifiable as tailored for heavy concentrations of either

Negro or white students. In short, in every case freedom of

choice has permitted the school board to maintain its tradi

tional system of racially identifiable schools.

II. The Affirmative Duty of the School Boards to Bring

About Integrated Unitary School Systems Requires the

Abandonment of Free Choice Plans and the Adoption of

Alternative Plans which Will Promptly Eliminate

Racially Identifiable Schools .__________________ _____

This Court, sitting en banc in Jefferson County,

held that school boards have the "affirmative duty under the

1/ Bossier Parish reported that one white student had en

rolled in the kindergarten of a Negro school this year.

Caddo reported that 35 white students were in Negro

schools, but 34 of them attend one school for the men

tally retarded.

Fourteenth Amendment to bring about an integrated, unitary

school system in which there are no Negro schools and no

white schools •— just schools." 380 F.2d 385, 389. The

Court mandated the entry of a comprehensive desegregation

decree. While the decree contained free choice provisions

for pupil assignment, the Court recognized that:

"Freedom of choice is not a goal in itself.

It is a means to an end. A schoolchild has

no inalienable right to choose his school.

A freedom of choice plan is but one of the

tools available to school officials at this

stage of the process of converting the dual

system of separate schools for Negroes and

whites into a unitary system." Id. at 390

(emphasis by the Court).

Freedom of choice must be recognized for what it

is -- an exceedingly strange technique of pupil assignment

whose only function is to soften the attitudes of white

Southerners to integration until a sensible method can be

used to bring about a unitary system. Until the first ten

tative step toward desegregation, of course, assignment of

students by geographical zones (but according to race) was

practically universal:

"In the days before the impact of the Brown

decis ion began to be felt, pupils were as

signed to the school (corresponding, of course

to the color of the pupils 1 skin) nearest

-6-

their homes; once the school zones and maps

had been drawn up, nothing remained but to

inform the community of the structure of the

zone boundaries." Moses v. Washington Parish

School Board. 2 76 F .Supp. 834,848 (E.D. La.

1967) .

See also Meador, The Constitution and the Assignment of

Pupils to Public School. 45 Va.L.Rev. 517 (1959):

"until now the matter has been handled

rather routinely almost everywhere by

marking off geographical attendance areas

for various buildings. In the South, how

ever , coupled with this method has been

the factor of race."

Not only is free choice an aberration born of a

supposed need to postpone the transition to a non-racial

system, it is a cumbersome administrative nightmare:

"Free choice systems, as every southern

school official knows, greatly complicate

the task of pupil assignment in the system

and add a tremendous workload to the already

overburdened school officials . . .

* * * * *

"If this Court must pick a method of assign

ing students to schools within a particular

school district, barring very unusual cir

cumstances , we could imagine no method more

inappropriate, more unreasonable, more need

lessly wasteful in every respect, than the

so-called "free-choice" system." Moses v.

Washington Parish School Board, supra, at 848,

851.

-7-

The principal vice of free choice, however, is

not that it is merely odd or inefficient, but that it per

mits the school board to escape its affirmative duty to

create a unitary system. It allows the board to shift the

burden of achieving desegregation freer* itself to the school-

children, and in particular in these cases, to the Negro

schoolchildren. Schools are "desegregated" only to the ex

tent that Negro children exercise their ”freedom of choice"

to attend "white" schools. "Rather than further the disman

tling of that dual system, the plan has operated simply to

burden children and their parents with a responsibility which

Brown II placed squarely on the School Board.M Green v.

County School Board of New Kent County, Virginia. 391 U.S.

430, 441-2 (1968).

In Green, the Supreme Court held that a free choice

plan is unacceptable "if there are reasonably available other

ways, such for illustration as zoning, promis ing speedier and

more effective conversion to a unitary, non-racial school sys

tem." 391 U.S. at 441. The Court said, echoing this Court

in Jefferson, that school boards are required "to convert

promptly to a system without a 'white1 school and a 'Negro1

school, but just schools." Id. at 442. And the conversion

-8-

is not to take place at some future time -- "the burden on a

school board today is to come forward with a plan that prom

ises realistically to work, and promises realistically to work

now." Id. at 439 (emphasis by the Court).

The Court1s holding in Green controls these cases.

The rej ection of the plan there turned on the fact that af

ter three years of free choice white students had not chosen

the Negro school and only 15% of the Negro students attended

the white school. Id. at 441. The instant cases cannot be

distinguished.^ In all but two of the fifteen cases here, at

least 86.5% of the Negro students attend all-Negro schools, and

3/in most cases the figure is more than 95%, In Lafayette

2/ Green cannot be distinguished on the ground that it in

volved a system with only two schools. The Court, in

enunciating the broad principles which condemn free

choice, made nothing of this fact and, in a companion

case, did not hesitate to strike down a similar plan

in a multi-school system. Monroe v. Board of Commis

sioners of Jackson, Tennessee, 391 U.S. 450 (1968).

3/ The precise percentages of Negro students in all-Negro

schools this year are as follows (see Appendix A):

Natchitoches 97.8% Acadia 94.5%

Evangeline 97.7 Iberia 91.3

Caddo 97.5 Calcasieu 90.2

Madison 97.4 Jefferson

St. Landry 97.0 Davis 87.0

St. Martin 96.4 St. Mary 86.5

Rapides 95.7 Lafayette 83.0

Bossier 95.6 Vermilion 56.0

-9

Parish 83% attend 10 all-Negro schools. In Vermilion Parish

44% of the Negro students attend predominantly white schools,

but this does not prove that freedom of choice is working, or

that some other plan would not work better. All of the other

Negro students in Vermilion attend one large all-Negro school.

The 44% figure was attained by the simple expedient of closing

two of the three all-Negro schools for this year, thus neces

sarily placing their former students in white schools. We do

not disparage this action by the Vermilion board; we merely

point out that closing all-Negro schools produces much more

dramatic results than freedom of choice.

Three decisions of this Court have already made it

plain that Green requires the abandonment of free choice in

every one of these cases. In Adams v. Mathews, which actu

ally involved some of the instant cases, the Court applied

Green and crystallized its rule as follows:

"If in a school district there are still

all-Negro schools, or only a small frac

tion of Negroes in white schools, or no

substantial integration of faculties and

schoo1 activities then, as a matter of law,

the existing plans fail to meet constitu

tional standards as established in Green."

403 F.2d 181, 188 (5th Cir. 1968) (emphasis

added).

-10-

The Court reiterated the test that any plan that leaves an

all-Negro school is unconstitutional in Graves v. Walton

County,_Board of Education. 403 F.2d at 189 (5th Cir. 1968).

Another panel of this Court, in recently ruling free choice

unacceptable, put it this way:

"We do say that a new plan must be devised to

eliminate the remaining, glaring vestige of a

dual system: The continued existence of all-

Negro schools with only a fraction of Negroes

enrolled in white schools." United States v.

Greenwood Municipal Separate School District,

No. 25714 (5th Cir. Feb. 4, 1969) (slip op. 14).

The racial identifiability test has also been ap

plied by the Eighth Circuit: "Perpetuation of the all-Negro

school in a formerly de jure segregated school system is sim-

ply constitutionally impermissible" Kemp v. Beasley. 389 F.2d

178, 183 (8th Cir. 1968) "The appellee School District will

not be fully desegregated nor the appellants assured of their

rights under the Constitution so long as the Martin School

clearly remains identifiable as a Negro school." Kelley v.

The Altheimer, Arkansas Public School District, No. 22, 378

F.2d 483, 490 (8th Cir. 1967).

These decisions correctly interpret the Brown and

Green cases. The Brown cases condemned not merely compulsory

racial assignments but also more generally the maintenance of

-11-

a dual public school system based on race — where some schools

are maintained or identifiable as being for Negroes and others

for whites. That students have been permitted to choose a

school does not destroy its racial identification if it pre

viously was designated for one race and continues to serve

only students of and is staffed primarily by teachers of that

race. Only when racial identification of schools has been

eliminated will the dual system have been disestablished. This

is the meaning of a system without a "white" school and a "Negro"

school, but "just schools." Green, supra, at 442.

Several judges in the Eastern District of Louisiana

have also recognized that the traditional all-Negro schools must

go and have ordered boards to develop, through the Educational

Resource Center on School Desegregation in New Orleans, new

plans eliminating them.^ As one judge said, the board:

4/ Banks v. St. James Parish School Board, No. 16173 (E.D.

La. Dec. 10, 1968; plan filed Jan. 31, 1969); Moore v.

Tangipahoa Parish School Board, No. 15556 (E.D. La.

Nov. 27, 1968; plan filed Jan. 27, 1969); Dunn v. St.

Charles Parish School Board, No. 67147 (E.D. La. Dec.

10, 1968; plan filed Jan. 31, 1969); Redman v. Terre

bonne Parish School Board, No. 15663 (E.D. La. Dec. 5,

1968; plan filed Jan. 31, 1969).

-12-

"can no longer postpone the desegregation of

these all-Negro schools in spite of the fact

that the present plan contemplates the event

ual phasing out of these schools. Rather, the

school board is now bound to integrate or aban

don these all-Negro schools by the commencement

of the school year for 1969-1970. . Moses

v. Washington Parish School Board, No. 15973

(E.D. La. Jan. 14, 1969).

These cases recognize reality: the dual system per

sists so long as there is a traditionally Negro school, possibly

named George Washington Carver or Booker T. Washington, with a

predominantly Negro staff and an all-Negro student body. Even

greater numbers of what the school boards call "cross-overs" --

an acknowledgment of duality — will not cause these schools

to disappear under a freedom of choice plan. Accordingly,

more promising alternatives must be tried. United States v.

Greenwood Municipal Separate School District, supra, slip op.

12.

The court below seriously misconceived the issue pre

sented . It said that the question was whether freedom of

choice plans "constitute adequate compliance with the Board's

responsibility 'to achieve a system of determining admission

to the public schools on a non-racial basis. . citing Brown

-13-

II, at 300 301 (opinion, p. 1). The issue is not whether ad

mission is determined on a non-racial basis. As the Supreme

Court said in Green, the fact that the school board in 1965

opened the doors" of all schools to all students "merely be

gins, not ends, our inquiry whether the Board has taken steps

adequate to abolish its dual, segregated system." 39.1 U.S.

at 437. The issue is one of remedies — what the school board

must do to meet its affirmative duty to disestablish a system

of racially identifiable schools. The Supreme Court said that

a racially neutral admission policy is not enough and that a

freedom of choice plan is not adequate if other methods promise

"speedier and more effective conversion to a unitary, nonracial

school system." Id. at 441.

The court below, in keeping with its statement of

the issue, did not even consider whether any alternative to

free choice would more effectively dismantle the dual system.

It acknowledged that not one of the school boards proposed an

alternative plan, but it failed to require the presentation of

alternatives. We submit that this completely undercuts

the court s approval of free choice. it also makes difficult

meaningful review by this Court. Clearly the court below should

-14-

have required the boards to present plans based on geographic

zoning or pairing or some other alternatives to free choice,

so that the court could compare the relative merits of the

alternatives. While we believe that freedom of choice must

be abandoned in any event (Greenwood, supra, slip op. 10, 12)

plainly the court erred in failing to consider whatever real-

5 /istic alternatives might exist in each case.—

The court also erred in failing to inquire into the

facts and circumstances of each individual case. The court

was content to say that free choice was "working" in most of

the parishes (opinion, p .5). But it lumped into its uniform

approval of free choice some very different factual patterns

5/ The court's statement that the school boards have been

admonished not to "tinker" with the Jefferson decree is

nonsense (opinion, p. 2). While this Court has resisted

attempts to modify the decree (see United States v.

Board of Education of the City of Bessemer, 396 F.2d 44

(5th Cir. 1968)), the boards' affirmative duty requires

them to use whatever method promises to undo segregation

not to cling helplessly to freedom of choice. See this

Court's en banc opinion in Jefferson, 380 F.2d 385; and

Judge Wisdom's opinion for the Jefferson panel:

"If school officials in any district should find

that their district still has segregated faculties

and schools or only token integration, their affirm

ative duty to take corrective action requires them to

try an alternative to a freedom of choice plan, such

as a geographic attendance plan, a combination of the

two, the Princeton plan, or some other acceptable sub

stitute . . . Freedom of choice is not a key that

opens all doors to equal educational opportunities."

372 F.2d at 895, 896.

-15-

which it chose not to examine, For example, it emphasized

that in Vermilion 44% of the Negro students attend previously

• 6 /all-white schools - But it ignored Evangeline Parish where

"integration" actually decreased this year: in 1967-68, 2.9%

of the Negro students attended white schools, but this year

the figure dropped to 2.3%. (There could hardly be better

proof that free choice does not disestablish the dual system.)

The court also disregarded Natchitoches Parish (2.2% this

year), where the proportion of integration decreased in sev

eral individual schools, where the school board opened a new

all-Negro school this year, and where the school board unabash

edly refused to honor the choices of Negro students until en-

7/joined by the court. Similarly, the court lumped together

large urban systems like Caddo with several small rural sys-

terns, while plainly a plan that might work in one place would

8 /be inappropriate in another. In short, the court erred in

6/ The court attributed this to the efficacy of free choice

rather than facing the reality that the school board sim

ply closed two of the three all-Negro schools this year.

7/ See the transcript of hearing of July 25, 1968, at pp.

3-5, 8-11, 22, and the order entered August 2, 1968.

8/ What "works" is what disestablishes the system of racially

identifiable schools. No one plan or even combination of

plans will accomplish this in every case. Cf. Board of

Public Instruction of Duval County, Fla, v. Braxton, 402

F.2d 900 (5th Cir. 1968); United States v. Greenwood

Municipal Separate School District, supra.

-16-

ignoring the very language which it quoted (p. 1) from

Green:

"There is no universal answer to complex problems

of desegregation; there is obviously no one plan

that will do the job in every case. The matter

must be assessed in light of the circumstances

present and the options available in each instance.

It is incumbent upon the school board to establish

that its proposed plan promises meaningful and

immediate progress toward disestablishing state-

imposed segregation. It is incumbent upon the

district court to weigh that claim in light of

the facts at hand and in light of any alternatives

which may be shown as feasible and more promising

in their effectiveness." 391 U.S. at 439 (emphasis

added).

The court below considered no alternatives and its

blanket approval of free choice must be reversed. The school

boards should be required to come in with alternative plans,

based on their individual local circumstances, which will actu

ally disestablish their system of racially identifiable schools

It goes without saying, of course, that the plans must be im

plemented for the school year 1969-70. Adams v. Mathews, supra

I I I . Specific Target Dates and Accomplishments for Faculty

Integration must be Required to Assure the Elimination

of Racially Identifiable Schools______________________

The decree mandated by the en banc decision of this

Court in Jefferson requires that "the pattern of teacher assign

ment to any school not be identifiable as tailored for a heavy

-17-

concentration of either Negro or white pupils in the school"

and directs school officials "to assign and reassign teachers

and other professional staff members to eliminate the effects

of the dual school system." 380 F,2d at 394. If the elimina

tion of racial identifiability or the conversion to a system

with "just schools" means anything, it must mean that a school

should not be racially identifiable by the composition of either

its students or faculty:

"The transformation to a unitary system will

not come to pass until the board has balanced

the faculty of each school so that no faculty

is identifiable as being tailored for a heavy

concentration of Negro or white students."

United States v. Greenwood Municipal Separate

School District, supra, slip op. 15-16.

In United States v. Board of Education of the City

of Bessemer, 396 F.2d 44 (5th Cir. 1968), this Court, per

Chief Judge Brown, said that it was erroneous for a district

court to consider the faculty integration issue as whether the

school board attempted in good faith to make substantial pro

gress . The Court held that school boards may not rely solely

on the "voluntary approach" but must forthrightly make assign

ments to meet the constitutional mandate, and that the district

court "has a duty to require specific interim target dates and

accomplishments" to assure that complete faculty integration

will be attained. See also Greenwood, supra, slip op. 16.

-18-

The court below ignored the explicit mandate of

Bessemer. Despite the fact that in every parish and even every

school the pattern of teacher assignment is readily identifiable

as intended for either white or Negro students, the District

Court specified no target dates or accomplishments at all

The school boards were told in effect that tokenism is accept

able and that there is nothing to worry about for the indefin

ite future. The court's decision provides no assurance at all

that the objectives established by Jefferson will be met any

time soon.

We believe that the adoption of plans effecting com

plete student integration will eliminate most obstacles to

faculty integration. The opposition by teachers to teaching

students of another race will be diminished if they are teach

ing in integrated classrooms. The Green decision envisaged

that faculty and student integration would proceed contempor

aneously — there would be "just schools." While Bessemer,

9/ In December of 1967, appellants moved in all these cases

for further relief requiring specific steps toward com

plete faculty integration. After hearings, relief was

denied in most cases, and appeals were taken. This Court

consolidated the appeals but denied appellants' motions

for summary reversal. See Jones v. Caddo Parish School

Board, 392 F.2d 723 (5th Cir. 1968). This Court, however,

stated that "some means must be provided by the trial court

to ascertain whether the requirements of Jefferson are to

be substantially complied with before it is too late to

affect teacher assignments for the next school year." Id.

at 723 (emphasis by the Court); see also Bessemer, supra,

at n.17. Appellants then pressed faculty integration in

the court below, but were denied relief by the decision

appealed from.

-19-

supra,, established 1970-71 as the date by which complete fac

ulty desegregation must be achieved, that opinion was written

without reference to, and apparently prior to the issuance of

the Green decision. Green requires that the transition to a

system without racially identifiable schools be effected "now."

Adams v. Mathews required complete integration for 1969-70 and

suggested steps to be taken during this school year. Therefore,

we submit that total faculty desegregation must be achieved for

the opening of school this fall

The question of the ultimate goal — what constitutes

complete faculty desegregation -- is presently before a panel

of this Court (Judges Wisdom, Bell and Godbold) on another ap

peal in the same three cases involved in the Bessemer decision

(Nos. 26582, 26583 and 26584, argued November 21, 1968). In

Montgomery County Board of Education v. Carr, 400 F.2d 1 (5th

10/ If, however, the Court adheres to the 1970-71 date men

tioned by Bessemer, "to assure compliance, it is evident

that the district judge will have to impose interim tar

gets and conduct subsequent hearings to determine what

progress is being made." Greenwood, supra, slip op. 16.

This, the court below has failed to do, and the absence

of explicit targets and deadlines accounts in large part

for the inadequate performance by the instant boards.

-2 0 -

Cir. 1968), another panel affirmed a district court order

requiring that there be at least one minority race teacher

for every five of the majority in each school by the begin

ning of the school year 1968-69, but reversed part of the

order requiring ultimately that the racial composition of

each faculty approximate the composition of the entire fac

ulty of the school system. On the latter point, this Court

split 6-6 on whether to grant reargument en banc, 402 F .2d

782, and petitions for certiorari were filed in the Supreme

Court.

We submit that the only effective means of carry

ing out the command of Jefferson to eliminate the racial

identifiability of faculties is to make all the schools'

faculties look substantially alike, so that each reflects

proportionately the racial composition of the entire faculty

of the school system. This was explicitly held in United

States v. School District 151 of Cook County, Illinois, 286

F.Supp. 786, 798 (N.D. 111. 1968), aff 'd___ F.2d ___ (7th

-21-

d r • 1968); accord Dowell v. School Board of Oklahoma City

Public Schools. 244 F.Supp. 971, aff'd 375 F.2d 158, cert,

denied 387 U.S. 931 (1967); Kier v. County School Board of

Augusta County, 249 F.Supp. 239 (W.D. Va. 1966). Perhaps

precise mathematical compliance is not feasible but substan-

tial proportionality is the only reasonable assurance that

faculties will no longer be racially identifiable. Having

created segregated faculties by unconstitutional hiring and

assignment policies, the school boards must now act forth

rightly to undo such segregation and eliminate the last

vestiges of the dual system.

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated, these cases should be re

manded to the District Court with instructions to require

each school board forthwith to submit an alternative plan,

not based on freedom of choice, for complete conversion to

a unitary nonracial system by the beginning of the school

year 1969-70. Such plan should eliminate all-Negro schools,

either by abandoning the physical facilities or by assign

ing to such schools substantial numbers of white students.

-22-

The plan should also require that in each school the ratio

of Negro teachers to white teachers will be substantially

the same as the ratio of Negro to white teachers in the

entire system. The plan should be filed before June 1,

so that appellants may file objections or amendments to

be promptly determined by the Court and the plan may be

fully implemented by the opening of the 1969-70 school

year.

Respectfully submitted,

JACK GREENBERG

NORMAN C. AMAKER

FRANKLIN E. WHITE

WILLIAM BENNETT TURNER

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A. P. TUREAUD

1821 Orleans Avenue

New Orleans, Louisiana

MURPHY W. BELL

214 East Boulevard

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

LOUIS BERRY

1406 East Ninth Street

Alexandria, Louisiana

MARION OVERTON WHITE

P. 0. Box 627

Opelousas, Louisiana

-23-

APPENDIX

\

APPENDIX A

1. Total school enrollment as of September 30,

1968 27,295

2. Total number of Negro students 6,984

3. Total number of white students 20,311

4. Total number of schools 35

5. Number of schools with exclusively

Negro students 10

6. Number of schools with exclusively

white students 4

7. Number of Negro students attending pre

dominantly white schools 1,195

8. Percentage of total Negro students attend

ing predominantly white schools 17%

9. Percentage of total Negro students who at-

tended predominantly white schools in

1967-68 10%

10, Number of white students attending pre

dominantly Negro schools 0

11. Number of white students who attended pre

dominantly Negro schools in 1967-68 0

Faculty

1. Total number of teachers 1,194

2. Number of Negro teachers 283

3. Number of white teachers 911

4. Number of Negro teachers assigned to

predominantly white schools 45

5. Number of white teachers assigned to

predominantly Negro schools 28

6 . Average number of teachers per school as

signed to schools predominantly serving stu

dents of a race other than their own 2.1

7. Number of schools with exclusively Negro

faculties 1

8. Number of predominantly white schools with

only one Negro teacher 7

9. Number of predominantly Negro schools with

only one white teacher

Lafayette Parish School Board

Students

1

Acadia Parish School Board

Students

1. Total school enrollment as of September

13, 1968 11,6242. Total number of Negro students 2,6943. Total number of whit® students 8,9304. Total number of schools 225. Number of schools with exclusively

Negro students 46. Number of schools with exclusively

white students 97. Number of Negro students attending pre-

dominantly white schools 1498. Percentage of total Negro students attend-

ing predominantly white schools 5.5%9. Percentage of total Negro students who at

tended predominantly white schools in

1967-68 2.2%10. Number of white students attending pre-

dominantly Negro schools 011. Number of white students who attended pre-

dominantly Negro schools in 1967-68 1

Faculty

1. Total number of teachers 516

2. Number of Negro teachers 127

3. Number of white teachers 389

4. Number of Negro teachers assigned to

predominantly white schools 23

5. Number of white teachers assigned to

predominantly Negro schools 12

6. Average number of teachers per school as

signed to schools predominantly serving stu

dents of a race other than their own 1.6

7. Number of schools with exclusively white

faculties 6

8. Number of predominantly white schools with

only one Negro teacher 6

Students

Iberia Parish School Board

1* Total school enrollment as of September

10, 1968

2. Total number of Negro students

3. Total number of white students

4. Total number of schools

5. Number of schools with exclusively

.Negro students

6. Number of schools with exclusively

white students

7. Number of Negro students attending pre

dominantly white schools

8. Percentage of total Negro students attend

ing predominantly white schools

9. Percentage of total Negro students who at

tended predominantly white schools in

1967-68

10. Number of white students attending pre

dominantly Negro schools

11. Number of white students who attended pre

dominantly Negro schools in 1967-68

14,967

4,897

10,070

30

11

4

42 6

8 .7%

6 . 2%

0

0

Faculty

1. Total number of teachers 661

2. Number of Negro teachers 231

3. Number of white teachers 430

4. Number of Negro teachers assigned to

predominantly white schools 24

5. Number of white teachers assigned to

predominantly Negro schools 2

6. Average number of teachers per school as

signed to schools predominantly serving stu

dents of a race other than their own .86

7. Number of schools with exclusively Negro

faculties 9

8. Number of schools with exclusively white

faculties 7

9. Number of predominantly white schools with

only one Negro teacher 2

10. Number of predominantly Negro schools with

only one white teacher 2

St. Martin Parish School Board

Students

1. Total school enrollment as of September

20, 1968 8,387

2. Total number of Negro students 3,516

3. Total number of white students 4,871

4. Total number of schools 15

5. Number of schools with exclusively

Negro students 7

6. Number of schools with exclusively

white students 1

7. Number of Negro students attending pre

dominantly white schools 128

8. Percentage of total Negro students at

tending predominantly white schools 3.6%

9. Percentage of total Negro students who at

tended predominantly white schools in

1967-68 3 - 2%

10. Number of white students attending pre

dominantly Negro schools 0

11. Number of white students who attended pre

dominantly Negro schools in 1967-68 0

Faculty

1. Total number of teachers 376

2. Number of Negro teachers 161

3. Number of white teachers 215

4. Number of Negro teachers assigned to

predominantly white schools 15

5. Number of white teachers assigned to

predominantly Negro schools 8

6. Average number of teachers per school as

signed to schools predominantly serving stu

dents of a race other than the ir own 1.5

7. Number of schools with exclusively Negro

faculties 3

8. Number of schools with exclusively white

faculties 1

9. Number of predominantly white schools with

only one Negro teacher 2

Students

St. Mary Parish School Board

1. Total school enrollment as of September

6* 1968 15,927

2. Total number of Negro students 5,390

3. Total number of white students 10,537

4. Total number of schools 26

5. Number of schools with exclusively

Negro students 9

6. Number of schools with exclusively

white students 1

7. Number of Negro students attending pre

dominantly white schools 729

8. Percentage of total Negro students attend

ing predominantly white schools 13.5%

9. Percentage of total Negro students who at

tended predominantly white schools in

1967-68 11.7%

10. Number of white students attending pre

dominantly Negro schools 0

11. Number of white students who attended pre

dominantly Negro schools in 1967-68 0

Faculty

1. Total number of teachers 701

2. Number of Negro teachers 246

3. Number of white teachers 455

4. Number of Negro teachers assigned to

predominantly white schools 52

5. Number of white teachers assigned to

predominantly Negro schools 12

6. Average number of teachers per school as

signed to schools predominantly serving stu

dents of a race other than their own 2.5

7. Number of schools with exclusively Negro

faculties 2

8. Number of predominantly white schools with

only one Negro teacher 1

9. Number of predominantly Negro schools with

only one white teacher 2

Vermilion Parish School Board

Students

1. Total school enrollment as of September

15, 1968 9,782

2* Total number of Negro students 1,644

3. Total number of white students 8,138

4. Total number of schools 18

5. Number of schools with exclusively

Negro students 1

6. Number of schools with exclusively

white students 2

7. Number of Negro students attending pre

dominantly white schools 722

8. Percentage of total Negro students attend

ing predominantly white schools 44%

9. Percentage of total Negro students who at

tended predominantly white schools in

1967-68 19.5%

10. Number of white students attending pre

dominantly Negro schools 0

11. Number of white students who attended pre

dominantly Negro schools in 1967-68 0

Faculty

1. Total number of teachers 433

2. Number of Negro teachers 62

3. Number of white teachers 3712

4. Number of Negro teachers assigned to

predominantly white schools 23

5. Number of white teachers assigned to

predominantly Negro schools 3

6. Average number of teachers per school as

signed to schools predominantly serving stu

dents of a race other than their own 1.4

7. Number of schools with exclusively white

faculties

8. Number of predominantly white schools with

only one Negro teacher 10

In 1968-69 this parish closed two Negro

schools which it maintained in 1967-68.

ro|

i—

Students

Rapides Parish School Board

1. Total school enrollment as of September

26, 1968 28,527

2. Total number of Negro students 9,671

3. Total number of white students 18,856

4. Total number of schools 51

5. Number of schools with exclusively

Negro students

6. Number of schools with exclusively

white students 16

7 . Number of Negro students attending pre

dominantly white schools 402

8. Percentage of total Negro students attend

ing predominantly white schools 4.3%

9. Percentage of total Negro students who at

tended predominantly white schools in

1967-68 3 • 3%

10. Number of white students attending pre

dominantly Negro schools 0

11. Number of white students who attended pre

dominantly Negro schools in 1967-68 0

Faculty

1. Total number of teachers 1,178.5

2. Number of Negro teachers 392

3. Number of white teachers 786.5

4. Number of Negro teachers assigned to

predominantly white schools 19.5

5. Number of white teachers assigned to

predominantly Negro schools 23.5

6. Average number of teachers per school as

signed to schools predominantly serving stu

dents of a race other than their own 1.2

7. Number of schools with exclusively Negro

faculties 4

8. Number of schools with exclusively white

faculties 5

9. Number of predominantly white schools with

only one Negro teacher 6

10. Number of predominantly Negro schools with

only one white teacher 6

This parish has maintained the same number

of all-Negro schools (19) as it maintained in

1967-68. In 1968-69, the parish has 2 additional

all-white schools, one of which, J. B. Nachman

Elementary, is open for the first time this year.

Students

Evangeline Parish School Board

1. Total school enrollment as of September

12, 1968 8,738

2. Total number of Negro students 3,114

3. Total number of white students 5,624

4. Total number of schools 14

5. Number of schools with exclusively

Negro students 5

6. Number of schools with exclusively

white students 2

7. Number of Negro students attending pre

dominantly white schools 71

8. Percentage of total Negro students attend

ing predominantly white schools 2.3%

9. Percentage of total Negro students who at

tended predominantly white schools in

1967-68 2.9%

10. Number of white students attending pre

dominantly Negro schools 0

11. Number of white students who attended pre

dominantly Negro schools in 1967-68 0

Faculty

1. Total number of teachers 416

2. Number of Negro teachers 142

3. Number of white teachers 274

4. Number of Negro teachers assigned to

predominantly white schools 19

5. Number of white teachers assigned to

predominantly Negro schools 12

6. Average number of teachers per school as

signed to schools predominantly serving stu

dents of a race other than their own 2.2

7. Number of predominantly Negro schools with

only one white teacher 2

This parish maintained the same number of all-

Negro schools (5) as it maintained in 1967-68. How

ever, in 1968-69, the parish is maintaining 2 all-white

schools which were integrated last year.

Students

St. Landry Parish School Board

1. Total school enrollment as of September

18, 1968 22,533

2. Total number of Negro students 10,754

3. Total number of white students 11,779

4. Total number of schools 43

5. Number of schools with exclusively

Negro students 20

6. Number of schools with exclusively

white students 3

7. Number of Negro students attending pre

dominantly white schools 330

8. Percentage of total Negro students attending

predominantly white schools 3%

9. Percentage of total Negro students who at

tended predominantly white schools in

1967-68 3%

10. Number of white students attending pre

dominantly Negro schools 0

11. Number of white students who attended pre

dominantly Negro schools in 1967-68 0

Faculty

1. Total number of teachers 1,031

2. Number of Negro teachers 484

3. Number of white teachers 547

4. Number of Negro teachers assigned to

predominantly white schools 23

5. Number of white teachers assigned to

predominantly Negro schools 21

6. Average number of teachers per school as

signed to schools predominantly serving stu

dents of a race other than their own 1.

7. Number of predominantly white schools with

only one Negro teacher 23

8. Number of predominantly Negro schools with

only one white teacher 19

This parish maintained the same number

of all-white schools (3) and the same number of

all-Negro schools (20) as it did in 1967-68.

Students

Natchitoches Parish School Board

1. Total school enrollment as of September

13, 1968 8,928

2. Total number of Negro students 4,601

3. Total number of white students 4,327

4. Total number of schools 26

5. Number of schools with exclusively

Negro students 10

6. Number of schools with exclusively

white students 7

7. Number of Negro students attending pre

dominantly white schools 101

8. Percentage of total Negro students attend

ing predominantly white schools 2 . 2 %

9. Percentage of total Negro students who at

tended predominantly white schools in

1967-68 2.1%

Faculty

1. Total number of teachers 548.07

2. Number of Negro teachers 247.07

3. Number of white teachers 301

4. Number of Negro teachers assigned to

predominantly white schools 29

5. Number of white teachers assigned to

predominantly Negro schools 33

6. Average number of teachers per school as

signed to schools predominantly serving stu

dents of a race other than their own 2.4

In 1967-68, this parish maintained 9

all-Negro schools. A new school, J.W. Thomas,

has been opened for the first time this year.

The Thomas school has an all-Negro enrollment,

increasing the number of all-Negro schools to

10.

Of the 29 Negro teachers assigned to pre

dominantly white schools, 14 of them have been

assigned to librarian work and 10 are reading

teachers.

Students

Caddo Parish School Board

1. Total school enrollment as of September

16, 1968

2. Total number of Negro students

3. Total number of white students

4. Total number of schools

5. Number of schools with exclusively

white students

6. Number of schools with exclusively

Negro students

7. Number of Negro students attending pre

dominantly white schools

8. Percentage of total Negro students at

tending predominantly white schools

9. Percentage of total Negro students who at

tended predominantly white schools in

1967-68

59,293

25,414

33,879

77

15

26

642

2 . 5%

1. 7%

Faculty

1. Total number of teachers

2. Number of Negro teachers

3. Number of white teachers

4. Number of Negro teachers assigned to

predominantly white schools

5. Number of white teachers assigned to

predominantly Negro schools

6. Average number of teachers per school as

signed to schools predominantly serving

students of a race other than their own

7. Number of schools with exclusively white

faculties

8. Number of predominantly white schools with

only one Negro teacher

2,507

1,099

1,408

96

66

2.1

2

2

This parish maintained the same number

of all-Negro schools (26) as it did in 1967-

68. It closed the Newton Smith Elementary

school, which had an all-Negro student enroll

ment , and added one all—Negro schoo1.

Bossier Parish School Board

1. Total school enrollment as of September

17, 1968 18,227

2. Total number of Negro students 4,268

3. Total nimber of white students 13,949

4. Total number of schools 24

5. Number of schools with exclusively

white students 5

6. Number of schools with exclusively

Negro students 5

7. Number of Negro students attending pre

dominantly white schools 188

8. Percentage of total Negro students attend

ing predominantly white schools 4.4%

9. Percentage of total Negro students who at

tended predominantly white schools in

1967-68 3*2%

10. Number of white students attending pre

dominantly Negro schools 1

11. Number of white students who attended pre

dominantly Negro schools in 1967-68 0

Faculty

1. Total number of teachers 827

2. Number of Negro teachers 213

3. Number of white teachers 614

4. Number of Negro teachers assigned to

predominantly white schools 33

5. Number of white teachers assigned to

predominantly Negro schools 22

6. Average number of teachers per school as

signed to schools predominantly serving stu

dents of a race other than their own 2.3

7. Number of schools with exclusively white

faculties 1

8. Number of predominantly white schools with

only one Negro teacher 1

This parish maintained the same number of

all-white schools .(5) as it did in 1967-68. In

1968-69, it opened a new school, Be11aire, which

has an all-white student enrollment. The number

of all-Negro schools maintained by the parish has

decreased by one school in 1968-69 — the Butler

School has one white student enrolled this year.

Students

Madison Parish School Board

(Williams v. Kimbrough)

Students

1. Total school enrollment as of September

20, 1968 4,490

2. Total number of Negro students 3,235

3. Total number of white students 1,255

4. Total number of schools 8

5. Number of schools with exclusively

Negro students 5

6. Number of schools with exclusively

white students 0

7. Number of Negro students attending pre

dominantly white schools 83

8. Percentage of total number of Negro stu

dents attending predominantly white

schools 2.6%

9. Percentage of total Negro students who at

tended predominantly white schools in

1967-68 2 .4%

10. Number of white students attending pre

dominantly Negro schools 0

11. Number of white students who attended pre

dominantly Negro schools in 1967-68 0

Faculty

1. Total number of teachers 218

2. Number of Negro teachers 137

3. Number of white teachers 81

4. Number of Negro teachers assigned to

predominantly white schools 5

5. Number of white teachers assigned to

predominantly Negro schools 13

6. Average number of teachers per school as

signed to schools predominantly serving stu-

dents of a race other than their own 2.25

7. Number of schools with exclusively white

faculties 1

8. Number of predominantly white schools with

only one Negro teacher 1

9. Number of predominantly Negro schools with

only one white teacher 1

Students

Calcasieu Parish School Board

(Lake Charles)

1. Total school enrollment as of September

4, 1968 38,545

2. Total number of Negro students 9,787

3. Total number of white students 28,758

4. Total number of schools 73

5. Number of schools with exclusively

white students 13

6. Number of schools with exclusively

Negro students 21

7. Number of Negro students attending pre

dominantly white schools 856

8. Percentage of total Negro students attending

predominantly white schools 9.8%

9. Percentage of total Negro students who at

tended predominantly white schools in

1967-68 7.67%

10. Number of white students attending pre

dominantly Negro schools 0

11. Number of white students who attended pre

dominantly Negro schools in 1967-68 0

Faculty

1. Total number of teachers 1,796

2. Number of Negro teachers 417

3. Number of white teachers 1,379

4. Number of Negro teachers assigned to

predominantly white schools 31

5. Number of white teachers assigned to

predominantly Negro schools 28

6. Average number of teachers per school as

signed to schools predominantly serving stu

dents of a race other than their own .8

7. Number of schools with exclusively Negro

faculties 16

8. Number of schools with exclusively white

faculties ' 34

9. Number of predominantly white schools with

only one Negro teacher 4

Students

Jefferson Davis Parish School Board

1. Total school enrollment as of October

16, 1968 8,045

2. Total number of Negro students 2,069

3. Total number of white students 5,976

4. Total number of schools 19

5. Number of schools with exclusively

Negro students 5

6. Number of schools with exclusively

white students 1

7. Number of Negro students attending pre

dominantly white schools 270

8 . Percentage of total Negro students attend

ing predominantly white schools 13%

9 . Percentage of total Negro students who at

tended predominantly white schools in

1967-68 8.3%

10. Number of white students attending pre

dominantly Negro schools 0

11. Number of white students who attended pre

dominantly Negro schools in 1967-68 0

Faculty

1. Total number of teachers 397

2 . Number of Negro teachers 110

3. Number of white teachers 287

4. Number of Negro teachers assigned to

predominantly white schools 11

5. Number of white teachers assigned to

predominantly Negro schools 2

6. Average number of teachers, per school as

signed to schools predominantly serving stu

dents of a race other than their own .7

7. Number of schools with exclusively Negro

faculties 3

8. Number of schools with exclusively white

faculties 2

9. Number of predominantly white schools with

only one Negro teacher 12

10. Number of predominantly Negro schools with

only one white teacher 2