Brief for Appellants; Affidavit of Paul Dimond

Public Court Documents

December 18, 1970

56 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Working Files. Brief for Appellants; Affidavit of Paul Dimond, 1970. 5415d7a5-54e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/bc840b4d-8ba2-4604-a14f-bd142280e7cc/brief-for-appellants-affidavit-of-paul-dimond. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

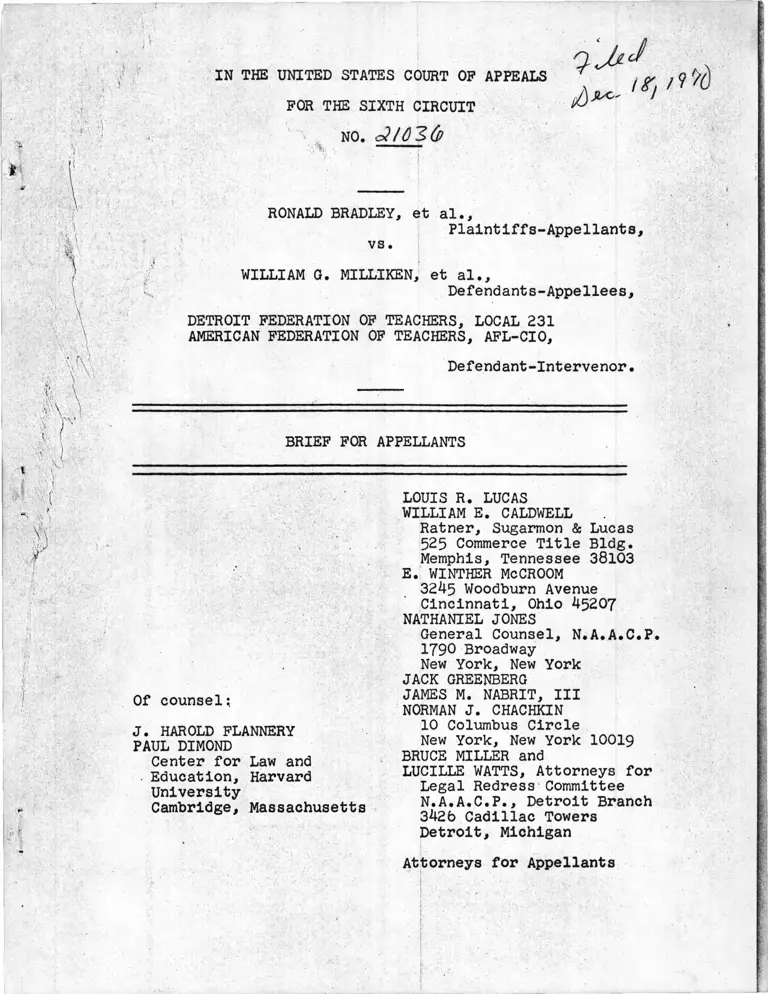

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OP APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

NO. c2/02(p

i?! I

RONALD BRADLEY,

vs.

et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees,

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, LOCAL 231

AMERICAN FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, AFL-CIO,

Defendant-Intervenor.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Of counsel;

J. HAROLD FLANNERY

PAUL DIMOND

Center for Law and

. Education, Harvard

University

Cambridge, Massachusetts

LOUIS R. LUCAS

WILLIAM E. CALDWELL .

Ratner, Sugarmon & Lucas

525 Commerce Title Bldg.

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

E. WINTHER McCROOM

3245 Woodburn Avenue

' Cincinnati, Ohio 45207

NATHANIEL JONES

General Counsel, N.A.A.C.P.

1790 Broadway New York, New York

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

BRUCE MILLER and

LUCILLE WATTS, Attorneys for

Legal Redress Committee

N.A.A.C.P., Detroit Branch

342b Cadillac Towers

Detroit, Michigan

Attorneys for Appellants

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Table of Cases................................... ii

Preliminary Statement .......................... 1

Issues Presented for Review .................... 3

Statement ...................................... 4

Procedural History .................. . . . 4

The Rulings Below .......................... 9

The April 7 P l a n ............................10

Alternative Proposals ....................... 14

A. The McDonald Plan .................... 15

B. The Campbell P lan....................18

C. Staff Proposals . .................... 19

Further Continuance of the Trial

on the Merits.................... 2.1

ARGUMENT . ............................ 25

Introduction ...................... . 26

The District Court's Postponement of Relief

Until September, 1971 Denies Plaintiffs' Constitutional Rights In Direct Violation Of The Rule Of Alexander v. Holmes County Board

of Education and Carter v. West Feliciana

Parish School Board . T .................... 28

The District Court Erred In Approving A Free

Choice Plan Despite Compelling Evidence That

The Technique Had Never Worked in Detroit,

And On The Explicit Ground of White Community

Hostility To Other, More Effective Means Of

Desegregation . . . . . ........ . . . . . . 32

Further Delay of The Trial On The Merits

Results In Denial Of Plaintiffs' Fourteenth

Amendment R i g h t s .......... ................42

Conclusion

Table of Authorities

Cases

Alexander v. Holmes County Bd. of Educ., 396 U.S.

19 (1969) .................................

Anthony v. Marshall County Bd. of Ed., 409 F.2d

1287 (5th Cir. 1969) ....................

Baird v. Benton County Bd. of Ed., 421 F.2d 700

(5th Cir. 1970) ..........................

Boykins v. Fairfield Bd. of Educ., 421 F.2d 1330

(5th Cir. 1 9 7 0 ) ............. .......... ..

Brunson v. Board of Trustees, Clarendon County,

429 F.2d 820 (4th Cir. 1970) . . . . . .

Brown v. Board of Educ., 347 U.S. 484 (1954);

349 U.S. 294 (1955) ......................

Buchanan v. Warley, 254 U.S. 60 (1917) ...........

Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Bd., 396

U.S. 226 (1969); 396 U.S. 290 (1970) . .

Charles v. Ascension Parish Sch. Bd., 421 F.2d 656

(5th Cir. 1970) ..........................

A. ■ . 'Christian v. Bd. of Ed. of Strong Sch. Dist. No.

83, #20038 (8th Cir., Dec. 8, 1970) . . .

Ex Parte Milligan, 71 U.S. 2 (1866) ...............

\ Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent County,

391 U.S. 430 (1968) . . . . .............

Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Bd., 417 F.2d 801

(5th Cir. 1 9 6 9 ) ............. .............

Hilson v. Ouzts, 421 F.2d 632 (5th Cir. 1970) . . .

Jones v. Caddo Parish Sch. Bd., 421 F.2d 313 (5th

Cir. 1970) ...............................

Jackson v. Marvell Sch. Dist. No. 22, 416 F.2d 380

(8th Cir. 1969)(en banc) ...............

Page

2,28,29,30,31,

37.38.42.43

34

29

2,29

40

30.37.43

40

28,29,30,31,34

38.43

29

30,31

43

17,20,37,38

34

29

29

31,34,40

Table of Authorities (Cases) - continued Page

Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, Denver, 303 F.Supp.

279, 289, 313 F.Supp. 60,91 (D. Colo.

1969-70) ........... 33,45,46

Lemon v. Bossier Parish Sch. Bd., 421 F.2d 121 (5th

Cir. 1 9 7 0 ) ................................. 34

Monroe v. Board of Comm'rs of Jackson, 391 U.S. 450

(1968); 427 F.2d 1005 (6th Cir. 1970) . . 39,40

Moses v. Washington Parish Sch. Bd., 421 F.2d 658

(5th Cir. 1970) ...................... 2

Nesbit v. Statesville City Bd. of Educ., 418 F.2d

1040 (4th Cir. 1 9 6 9 ) ....................... 31,43

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School

Dist., 419 F.2d 1211 (5th Cir. 1969) . . . 2,34

Spangler v. Pasadena City Bd. of Educ., 311 F.

!' Supp. 501 (C.D. Cal. 1970) . . ........... 46

\ Stanley v. Darlington County Sch. Dist., 424 F.2d

195 (4th Cir. 1970) ................... . 30,31

Steele v. Bd. of Public Instr. of Leon County,

421 F. 2d 1382 (5th Cir. 1969) ........... 33

/ United States v. 'Board of Educ. of Baldwin County,

423 F.2d 1013 (5th Cir. 1 9 7 0 ) ........... 31,33,39

United States v. Sch. Dist. 151 of Cook County,

111., 286 F.Supp. 786; 404 F.2d 1125;

301 F.Supp. 2 0 1 .......................... 46

United States v. Sch. Bd. of Franklin City, 428

F. 2d 373 (4th Cir. 1 9 7 0 ) ................. 2

United States v. Greenwood Municipal Separate

School Dist., 422 F.2d 1250 (5th Cir.

1970) ..................................... 29,34

United States v. Hinds County Sch. Bd., 423 F.2d

1264 (5th Cir. 1969) .................. .. . 31,40

Valley v. Rapides Parish School Bd., No. 30099

(5th Cir., August 25, 1970) ........... . . 29,47

Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U.S. 526 (1963) . . . 28,40,42

Table of Authorities (Cases).- continued Page

Williams v. Iberville Parish Sch. Bd., 421 F.2d

161 (5th Cir. 1 9 7 0 ) ...................... 29

Williams v. Kimbrough, 421 F.2d 1351 (5th Cir.

1 9 7 0 ) ..................................... 29

Walker v. County Sch. Bd. of Brunswick County,

413 F.2d 53 (4th Cir. 1 9 7 0 ) ............ 34,40

iv

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

, NO. _____

RONALD BRADLEY, et al.,

Plaintiffs-AppeHants,

vs.

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees,

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, LOCAL 231

AMERICAN FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, AFL-CIO,

Defendant-Intervenor.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Preliminary Statement

Appellants file this Brief both as their submis

sion in chief to this Court on the pending appeal, and also

in support of their Motion for Summary Reversal or in the

Alternative for Injunction Pending Appeal, and for Leave to

Proceed Upon the Original Papers filed herewith.

The necessity for expedited action by this Court

arises because this is an appeal from the denial of the motion

below seeking implementation of the April 7, 1970 plan of

school desegregation exactly as adopted and unrescinded by the

Detroit School Board. Extraordinary procedures shortening

th§ normal processing time for an appeal are required if

tenth graders are to be accorded their Constitutional right

to attend a high school with an improved racial balance effec

tive with the February 1, 1971 commencement of the second

semester of the current school year. Failure to give such

relief would be to give full force and effect to the first

sentence of Section 12 of Act 48 of the 1970 Michigan Legis

lature — a provision ruled unconstitutional by this Court on

October 13, 1970 in Bradley v. Mllllken, ___ F.2d __ , No.

20794 (6th Cir., October 13, 1970).

There is ample precedent in this and other Circuits

for expeditious appeal in school desegregation cases. E.g.,

Bradley v. Milliken, supra; Singleton v. Jackson Municipal

Separate School Dlst., 419 F.2d 1211, 1222 (5th Cir. 1969);

Boykins v. Fairfield Bd. of Educ.. 421 F.2d 1330, 1331 n.l,

1332 (5th Cir. 1970); United States v. School Bd. of Franklin

City, 428 F.2d 373 (4th Cir. 1970). Appellate procedures

should be "suitably adopted" to follow the "immediacy" require

ment of the substantive law as stated in Alexander v. Holmes

County Bd. of Educ., 396 U.S. 19 (1969). See Moses v. Wash

ington Parish School Bd., 421 F.2d 658 (5th Cir. 1970).

. . ■ • . • . • • ‘ ’ ’ • ., '• ■ :■ . ■ , ; . i . ■ ' : • , ~ - ' /■ / ’ . : . : ■ ! Y. '

2

Issues Presented for Review

On April 7, 1970, the Detroit Board of Education

adopted a high school desegregation plan affecting twelve

Detroit high school entering-tenth-grade classes in September,

1970. The operation of that plan was suspended prior to its

implementation by Section 12 of Act 48 of the 1970 Michigan

Legislature. October 13, 1970, on appeal from the district

court's denial of a preliminary injunction, this Court declared

that section of the law unconstitutional and remanded the

cause. December 3, 1970, the lower court denied plaintiffs'

motion to implement the April 7 plan for the second semester

of the current school year, delayed the trial on the merits

a second time, and ordered into September, 1971 effect a "free

choice" plan.

1. Did the court below err in perpetuating, for

the second semester of the 1970-71 school year, the racial

separation of pupils effected by Act 48?

J \/ 2. Did the court below err in granting defendants'

motion'for a second continuance of the trial on the merits?

Statement

Procedural History

This action was commenced August 18, 1970 to deseg

regate the public schools of the City of Detroit. The matter

was tried August 27, 1970 before Honorable Stephen J. Roth,

United States District Judge, on plaintiffs-appellants'

1/ 2/Motion for Preliminary Injunction. (A. 1 J- 7 September 3,

1/ This action is a classic Fourteenth Amendment suit seek

ing complete desegregation of the Detroit public school

system, as well as declaratory and injunctive relief against

certain provisions of Act 48 of the 1970 Michigan Legislature.

By way of preliminary relief, plaintiffs sought to: (1) en

join defendants from giving any force or effect to 912 of Act

48; (2) require September, 1970 implementation of the April 7

partial high school desegregation plan on an accelerated basis,

eliminating therefrom the three-year stair-step approach and

the brother-sister exception; (3) enjoin defendants from im

plementing the eight racially segregated administrative

regions drawn pursuant to Act 48, or from taking any steps

which would impair implementation of the seven racially inte

grated regions as adopted by the defendant Board on April 7,

1970; (4) enjoin the defendant Board from all further school

construction until a Constitutional plan of operation had been

approved; (5 ) require September, I97O assignment and/or

reassignment of faculty members in accordance with the system

wide ratio of black and white faculty members.

The district court scheduled the August 27 hearing as a

full trial on the merits, but on the second day of the hear

ing (August 28, 1970), the court limited its scope to the

matters presented in plaintiffs' Motion for Preliminary In

junction. The thrust of plaintiffs' presentation on the

trial days of August 28 and September 1, 1970 was directed at

912 of Act 48 and implementation of the April 7 plan by the

commencement of the school year, which began on September 8,

The relationship of 912 of Act 48 to the April 7 plan (i.e.,

§12 suspended and, in effect, prohibited implementation and

operation of the April 7 plan) is set out in this Court's

October 13, 1970 opinion. Bradley v. Milliken, supra, slip op. at pp. 5-8, 13.

2/ "A. __" references are to the Appendix to this Brief. By

separate motion filed herewith, plaintiffs seek leave to

-4-

t

1970, the district court denied the motion for preliminary

relief and dismissed the action as to the Governor and

Attorney General of Michigan.

Plaintiffs immediately appealed to this Court; the

matter was heard by the Chief Judge upon plaintiffs' Motion

for Injunction Pending Appeal, and then by a panel of this

Court on an expedited basis pursuant to the order of the

3/Chief Judge denying the Motion. October 13, 1970, this

Court reversed the judgment of the district court insofar as

it dismissed the State defendants and insofar as it upheld

the constitutionality of §12 of Act 48. The district court's

denial of plaintiffs' motion for preliminary injunction was

affirmed, however, because

The complaint in the present case seeks relief

going beyond the scope of the plan of April 7,

1970, and Act 48, such as the assignment of

teachers, principals and other school personnel

2/ (continued) proceed on the original papers without the

necessity of filing the Appendix required by Rule 30,

F.R.A.P.. See Rule 30(f), F.R.A.P.. Due to printing limi

tations, plaintiffs are filing only four (4) copies of the

Brief Appendix at this time but will submit additional

copies as soon as they are reproduced.

3/ The Motion for Injunction Pending Appeal, heard in Nash

ville on September 8, 1970 before the Chief Judge pursuant

to Rule 8, F.R.A.P., sought only to enjoin the effect of @12

of Act 48 insofar as it impeded implementation of the April 7

plan and to preserve the status quo by immediate implementation of the plan. In his September 11 order denying the Motion,

the Chief Judge advanced the appeal for hearing on the merits

before a panel of this Court on October 2, 1970 (A. 5 ).

to each school In accordance with the ratio

of white and Negro personnel throughout the

. Detroit school system, and an injunction

against all future construction of public

school buildings pending Court approval. As

previously stated, the District Judge not

only conducted an expeditious hearing on the

application for a preliminary injunction,

but has advanced the case on his docket to

November 2, 1970 and allotted two weeks for.,

the trial. (it/)

We conclude that the issues presented in

this case, involving the public school

system of a large city, can best be determined

only after a full evidentiary hearing.

Bradley v. Mllllken, supra, slip op. at p. 14.

Upon remand, plaintiffs filed in the district court

on October 30, 1970 a motion limited to requesting immediate

5/implementation of the April 7 plan. November 4, 1970, the

district court continued the trial on the merits to December

8 and conducted instead a hearing on plaintiffs' motion to

6/implement the April 7 plan.

4/ The November 2 trial date was subsequently changed by the

district court to November 4 because of a judges' conference .

5/ This motion did not seek elimination of the stair-step

and brother-sister features of the April 7 plan but

merely implementation of the plan as to students who entered

the tenth grade in September and as to those who will enter

the tenth grade at the beginning of the second semester, February 1, 1971.

6/ Plaintiffs acquiesced in the continuance upon the basis

that the district court set a definite December trial date.

At that hearing, Superintendent Drachler testified

that his staff was studying the April 7 plan in light of the

pupil racial count which had just been completed, in an ef

fort to determine whether the April 7 plan needed certain

i

modifications so as to accomplish the desired result (11/4 Tr.

7/

38-40). At the conclusion of the hearing, the district

court took under advisement the motion to implement the April

7 plan, stating that

(i)n order to provide the Board of Education

with an opportunity to demonstrate what Mr.

Bushnell (Detroit Board's attorney) says

they are planning to do and what they hope to

do and what they hope to achieve in the way

of implementing the April 7, Plan or an updated

version of it, I will give the Board an op

portunity to, not later than November 16,

submit a plan which the Court may find accept

able and one designed to become effective as,u/ n /\ of February 1, 1971 (A. 16 ). \2/* 2/•

November 6, 1970, the district court entered an order

requiring

that no later than November 16, 1970,

Defendant Detroit Board of Education submit

7/ The transcripts of tne three hearings in this cause nave

not been paginated consecutively. Transcript citations

are therefore preceded by the date on which each hearing

commenced. The first hearing was held August 27, 28 and

September 1, 1970; the second, November 4, 1970; and the

third, November 18, 19 and 25, 1970.

8/ That portion of the November 4 transcript containing the

district court's oral ruling was typed separately and is

reproduced in the Brief Appendix, A. 15 -20 .

9/ The district court's reference to "what Mr. Bushnell says

they are planning to do" relates to statements similar to

the following: "And there has been a consensus as between

board superintendent and counsel that this board in light of

the Court of Appeals decision is under an obligation to

either implement the April 7 plan or its equivalent, depend

ing upon how the facts develop . . . " (11/4 Tr. 27). See

also, 11/4 Tr. 53; 11/4 Tr. 55; 11/4 Tr. 56. ---

-7-

a high school attendance area plan to this

Court consisting of that portion of tne

action taken by Defendant Detroit Board of

Education on April 7, 1970, going to the

changing of attendance areas of certain

named high schools in the City of Detroit,

or an updated version thereof which achieves

no less pupil integration; the said plan

To be submitted to this Court is to become

effective and shall be implemented on the

first day of the Spring Semester of the school

year 1970-1971, being February 1, 1971. (A.

21 )(emphasis supplied).

November 16, 1970, following a special Board of

Education meeting, counsel for the Board filed, in addition

to the April 7 (Plan "C") plan of integration,-^^ two addi

tional plans referred to respectively as the "McDonald Plan"

(Plan "A" or "Magnet School Plan") and the "Campbell Plan"

(Plan "B" or "Magnet Curriculum Plan") (A. 23 -39 ). At its

meeting, the Board designated "priorities," assigning top

priority to the McDonald Plan, followed by the Campbell Plan

and the April 7 plan. The district court conducted a hearing

on the plans November 18, 19 and 25, 1970.

November 19, 1970, the Detroit Board filed a motion

to continue the trial on the merits "from December 8, 1970 to

a date certain on or after Monday, January 18, 1971" (A. 40 ).

Plaintiffs opposed the motion for continuance (11/18 Tr. 236).

At the conclusion of the evidence and following

arguments of counsel on November 25, 1970, the district court

10/ The April 7 plan is contained in plaintiffs' Complaint as

Exhibit D thereto (A. 49 ) and also in the official minutes

of the April 7» 1970 meeting of the Board (Defendants' Exhibit

F, A. 6 3 - 6 5 ) .

took the case under advisement but stated that the pretrial

conference which had been set for December 3, 1970 would go■ /V

on as scheduled (11/18 Tr. 368). On that date, however, the

conference was obviated by the court*s "Ruling on School Plans

Submitted" (A. 90 ) and "Ruling on Motion for Continuance"(A.

100). The same day, the district court entered its order in

accordance with the rulings (A. 102) and plaintiffs filed■ ■

Notice of Appeal (A. 104).

The Rulings Below

In its "Ruling on Motion for Continuance" the dis

trict court granted the Board's motion "for a continuance to

a date to be fixed by the Court"; counsel for plaintiffs were

subsequently advised in Chambers that the trial would take

place some time in late March or April, the exact date to be, .. . ■ | • ■ '

fixed at a later time.

In its "Ruling on School Plans Submitted," the

district court, despite its finding "that any action or failure

to act by the Board of Education designed in effect to 'delay,

obstruct or nullify' the previous (April 7th) step toward

improving racial balance in the Detroit schools is prohibited

State a c t i o n , a p p r o v e d the McDonald Plan and ordered that

11/ The court also held, on the basis of this Court's October

13 decision and the cases cited by this Court in its

opinion (slip op. at pp. 10-1 1 ), that "where a school district

has taken steps enhancing integration in its schools it may

not reverse direction. In the setting of our case nonaction

is (or amounts to) prohibited action" (A. 98 ).

# f

■ • ' ■ .■ ' I ■ ■ ■ ' ' ■: ■ : ■ ■ ■ • •

-9-

• ' . . I ‘ . ' . .

"preparations should be started immediately for its insti

tution at the beginning of the next full school year in

September 1971'* (A.98-99)(emphasis supplied).

The April 7 Plan

This Court already has considerable familiarity with

the April 7, 1970 plan of high school desegregation from the

previous proceedings in this cause. By way of reiteration,

the April 7 plan provided changes which would "affect 18

junior high school feeder patterns out of 55 and will influence

12 senior high schools" (Defendants' Exhibit F at 504, A. 64 ).

The passage of time has not made any basic change in

the effect. The staff task force report (see n.25 infra)

describes the situation as follows:

Although changes in racial percentages have

occurred during the past year, the relation

ship of the paired schools in that plan are

still, relatively, the same. (12/) That is,

Redford, Cody, Osborn, Denby, Western and Ford

have a significant majority of white students.

Mackenzie, Cooley, Mumford, Pershing, Kettering

and Southwestern have a preponderance of black

students. It should be noted that all boundary

changes occur within the established eight re

gions, with the exception of the Denby-Kettering,._ yv

areas. (Plaintiffs' Exhibit 13, A. 123). \±2/)

12/ An increase in racial isolation in Detroit's high schools

was noted by Superintendent Drachler at the November 4

hearing (11/4 Tr. 5).

13/ "If, the April 7 plan is compared to the current 8-region

organization, it is apparent that all facets of that plan may be initiated within the current organization, except Denby-

Kettering. The fact of a violation of region boundaries as a

requirement to re-institute April 7 should not be a major de

terrent to carrying out the plan. Precedent exists currently

in the Post-Cooley, Burroughs-Kettering, and the Vernor-

Vandenberg-Ford combinations for student attendance areas which do not fit adult voting areas." (plaintiffs' Exhibit ll, A. 126)*

■ . ' ■ V ■. . . j ' • ■ ■ < '

-10-

The April 7 plan would be effectuated by changing

the attendance area boundary lines separating the twelve

high schools from a north-south to an east-west direction

(11/4 Tr. 38), affording more efficient utilization of exist

ing public transit routes in Detroit (11/18 Tr. 254-55). It

would involve the movement of only 1% of Detroit’s public

school enrollment for the 1970-71 school year (8/27 Tr. 222,

231) and would affect only 3# to 4# of the total system popu

lation over the three-year full implementation period (8/27 Tr

232-33). The plan would not cause any increase in the number

of schools operating on extended-day sessions (11/18 Tr. 295);

with a few individual exceptions, there would be no problem of

subject-matter continuity for those students who would change

schools under the plan (11/4 Tr. 8-9); it would not require

building or equipment changes (11/4 Tr. 13); and only one or

two teacher changes would be necessitated by the April 7 plan

(11/4 Tr. 16).

The following table demonstrates the effect of the

April 7 plan as compared to the current enrollment and

racial composition of Detroit's 21 attendance-area high

schools:

11

High Schools*

Current Enrollment**

Total Black % Black

Projected

% Black

Without April

7 Plan***

Projected

% Black

Under April

7 Plan****

1. Central 2140 2140 100% -

2. Chadsey 1654 907 54.8%

3. CODY 3516 141 4% 3.3% 9.7%

* 4. COOLEY 2876 2192 76.2% 61.5% 53%

5. DENBY 2949 73 2.5% 2.4% 19.3%

6. Finney 2658 973 36.6%

7. FORD 3082 617 20% 13.5% 16.3%

8. KETTERING 3472 3373 97.1% 91.4% 81.3%

9. King 1879 1876 99.8%

10. MACKENZIE 3250 3145 96.8% 90.7% 83.8%

11. MUMFORD 3059 3001 98.1% 95.8% 94.9%

12. Murray-Wright 2072 1974 95.3%

13. Northeastern 1437 1339 93.2%

14. Northern 1767 1748 98.9% ' ;

15. Northwestern 2981 2977 99.9%

16. OSBORN 3071 431 14% 17.5% 22.6%

17. PERSHING 3244 2069 63.8% 58.3% 50.9%

18. REDFORD 3781 107 2.8% 3.6% 11.4%

19. Southeastern 2710 2630 97%

20. SOUTHWESTERN 1767 1312 74.3% - 71.3%

21. WESTERN 2241 827 36.9% ' — 39.2%

* The underlined schools are the twelve high schools affected

by the April 7 plan.

** The "Current Enrollment" columns are taken from the defendant

Board's Oct. 1970 racial count (Plaintiffs' Exhibit 10) and the

percentages are computed therefrom.

*** This column is taken from the "Without Change" columns of the

April 7 plan (Exhibit D to Complaint; A. 58 - 60 ) and repre

sents the Board's April 7, 1970 projections as to the 1970-71

racial composition of the 12 high schools without the April 7

plan.

**** This column represents the April 7, 1970 projections as to the

effect of the April 7 plan on the 12 high schools. (Exhibit D

to Complaint; A. 58 - 60 ) .

. ! ■' ■

■ -12-

At the November 4 hearing, Superintendent Drachler

reiterated his belief that integration is a necessary ingred

ient of quality education (see Bradley v. Mllllken, supra, slip

op. at pp. 3-4), stating that the April 7 plan was good and

that it was his hope the Board would select a plan of inte

gration along April 7 lines (11/4 Tr. 29). The Superintendent

apparently now feels, however, that no plan should be imple

mented until next September because of administrative difficul

ties (11/18 Tr. 288, 295* 315), although he testified on

September 1, 1970 (seven days before the school year began),

that his staff "would need anywhere from four to six days to

reschedule these approximately 3000 students (who would be

affected by the April 7 plan)" (8/27 Tr. 224). The Superin

tendent also testified at the first hearing that 50 to 100

attendance area changes are made each year (8/27 Tr. 188-91) w

Another member of the school administration and

two School Board members with training in education, supported

15/the April 7 plan.

14/ In contrast to the procedure followed with regard to the

April 7 feeder pattern changes for the purpose of inte

gration, the Superintendent normally makes changes in feeder

patterns every semester without Board approval (11/18 Tr. 225).

15/ Board Member Dr. Cornelius Golightly, Associate Dean of

the College of Liberal Arts and Professor of Philosophy at

Wayne State University (11/18 Tr. 151) and a member of the

Milwaukee Board of Education for six years (11/18 Tr. 155),

testified that the April 7 plan "is educationally sound" and

"in terms of the plans presented it is simple, straightforward,

involves established and proven ways in which you would inte

grate . . . ." (11/18 Tr. 156-57, 159-60).

Board Member Gardner, an attorney with a Master's Degree in Education who taught for 8 years in Detroit's public schools

(11/18 Tr. 2l6, 218), testified that in his opinion "implemen

ting the April 7, plan would bring about the immediate

The April 7 plan is the only one existing which

has been worked out logistically and which has detailed pro

cedures for implementation. It is the only plan that will

affect, by February, 1971* the students deprived of their

' ■ ■ ■ ■; . ■ .. / .........'

constitutional rights by §12 of Act 48.

Alternative Proposals

As previously stated, the Detroit Board on November

16, 1970 submitted two alternatives to the April 7 plan: the

McDonald Plan and the Campbell Plan. Although the Board

superficially assigned top priority to the McDonald Plan, four

of the seven Board members who testified at the last hearing

preferred plans other than the McDonald Plan: Campbell (11/18

15/ (continued) required integration and that at the very same

time one of the other plans can be included and join with

the April 7, plan to give a wider integration to the system"

(ll/l8 Tr. 217. See also, 11/18 Tr. 167-68 (Dr. Golightly);

II/18 Tr. 99 (Mrs. Campbell)). "(T)he April 7, plan could be

implemented faster and more complete than the other two plans.

I think it is less expensive and actually causes least movement

than any of the other plans and it is just a matter of being

a little simpler to accomplish" (11/18 Tr. 219. See also, 11/18

Tr. 172*73 (Dr. Golightly)).

Dr. Freeman A. Flynn, Divisional Director of the Department

of Intergroup Relations in the system's Division of School-

Community Relations, who has been a teacher, department head,

assistant principal and principal prior to assuming his present position in 1908 (11/18 Tr. 245), also testified in favor of

the April 7 plan. Although he felt it "was a modest effort at

desegregation," he favored the April 7 plan because he "felt

that given the social dynamics of the community the plan might

address itself to those social dynamics and might tend to im

prove the emotional climate and psychological climate of the

schools" (11/18 Tr. 253). As a professional educator, he felt "that the April 7, plan is a reasonable program for the school

system to adopt" (11/18 Tr. 257). He supported it at the time

it was adopted (11/18 Tr. 253) and believes "it is a reasonable

plan to adopt in February" (11/18 Tr. 258). Dr. Flynn found

that under the plan "there are probably no students who would

have to go further to school than what students currently do who attend Finney High School or Southwestern High School under

the currently operating high school plan" (11/18 Tr. 276).

-14-

f

Tr. 108-10); Rambo (11/18 Tr. 141-47, 149-50); Golightly

(11/18 Tr. 156-57, 159-63); Gardner (11/18 Tr. 217-18).^

. -i- . t ’ : .

A. The McDonald Plan

The district court described the McDonald Plan as

follows (A. 94 - 95):

The McDonald Plan is intended to achieve inte

gration by providing a specialized curriculum

at certain high schools. Each of such special

izing schools would serve two of the eight

regions of the school system, with the expecta

tion of drawing students from a wider area,

thus bringing about a built-in and, hopefully,

a greater degree of integration. The categories

of specialization would be Vocational, Business,

Arts and Science. The plan is voluntary, and

all high schools, including the so-called magnet

schools, would offer a reguTar“high school

curriculum for student's "living in the present

high school attendance areas, "(emphasis supplied)

The McDonald Plan on the other hand, we believe,

offers the student an opportunity to advance in

his search for identity, provides stimulation

through choice of direction, and tends to estab

lish security. (17/) That it will promote

integration to the extent projected remains to

be seen, but based on the experience in this

16/ Member McDonald, of course, preferred his plan (11/18 Tr.

20), while Board President Hathaway, preferred either the

McDonald or Campbell Plan over the April 7 plan (11/18 Tr.

229, 231, 232). (Both have opposed the April 7 plan since its

inception). Member Mogk expressed no preference (11/18 Tr.

173-79)* Thus, only two members actually expressed any sort

of preference for the McDonald Plan. (Compare the district

court’s finding that the Detroit Board "has "on its own shown

a preference for the McDonald Plan . . ." (A. 95 )).

17/ These "identity," "stimulation" and "security" criteria

are nowhere found in the record, in the form of expert

testimony or otherwise, but apparently stem from the District

Judge's personal views on education and what the law ought to be.

-15-

same school system, i.e., Cass Technical

High School (18/) it holds out the best

, promise of effective, long-range integration.

. It appears to us the most likely of the three

plans to provide the children of the City of

Detroit with quality education as we have

defined it. The McDonald Plan has been char

acterized by the plaintiffs as an experiment.

The short answer to this is that all plans

are experiments, just as is life itself. To

sum up, in our view the McDonald Plan is the

best of the plans before the Court.

The plan "is based upon the concept of excellence in education

acting as a magnet to voluntarily draw students of all races

and socio-economic classes together for educational progress"

(A. 25 )(emphasis supplied). Parents desiring to send their

children to another high school would bear transportation

expenses, unless the majority of the parents in a particular

region favored transportation at Board expense (11/18 Tr. 55).

However, four of the current seven Board members believe that

the McDonald Plan would not result in pupil integration because

19/, 20/of its "free choice" aspects.—

18/ See pp. 34 -35 infra.

19/ Board member Campbell criticized the voluntary aspect of

the McDonald Plan on this basis: "It seems to me that

the specialization, that students would voluntarily leave the

familiar and move into a strange situation for their entire

high school career because it had a better teacher or because

it had more automobile engines than their home school had. I

find that assumption difficult to accept" (11/18 Tr. 108).

Two of Mrs. Campbell's responses to the district court's questions are representative:

THE COURT: You put it in this focus, then, as

I see it, basically the difference between the approach

in Plan B, and Plan A, is that Plan A is purely voluntary, isn't it?

A. That's correct. (11/18 Tr. 109)

'» ‘ '' ' , I ' . • ' . .

} ' 1 I ' • . ' *

A concept similar to the current McDonald Plan

was previously rejected as a substitute to the April 7 plan

by the Detroit Board as it was constituted on April 7, 1970.

,

19/ (continued)

THE COURT: . . .It's your Judgment that the

voluntary aspect of the plan will be its defeat

so far as substantial progress is concerned, that

is, Plan A; that that is really the achilles heel

of Plan A. You don't think it will bring forth

the response that is expected.

A. That's correct. (11/18 Tr. 110).

Board member Rambo, in reference to the voluntary aspect

of the McDonald Plan, said: "my reading of past experience in

other places leads me to feel that it would not be an unsound

thing to consider some — and you (the Court) used the term —

help in the choice of selecting a curriculum, help possibly from the system" (11/18 Tr. 14b).

Similarly, Board member Golightly had reservations about

the voluntary aspects of the McDonald Plan and preferred the

April 7 plan as a plan of school desegregation (11/18 Tr. 167).

Board member Gardner preferes the April 7 plan supplemented by

the Campbell Plan "because I happen to believe that no inte

gration will occur in the City of Detroit if there is not an

element of requirement. I think the voluntary concept of the

A plan proposed by member McDonald . . . it is impractical in

this world today and particularly in the City of Detroit to accomplish integration" (11/18 Tr. 217-18).

20/ The McDonald Plan as presented to the district court also

contained a proposal for February 1, 19 71: that "all

senior high schools shall be open to enrollments which will

contribute to the integration of the school up to a total 125#

of their capacity . . . with the further provision that any

high school already in excess of 125 per cent shall receive

open enrollments up to 10 per cent over their current enrol

lment" (A. 31 ). Plaintiffs urged that any plan of integration

which placed the burden on black children and their parents

would be unconstitutional (11/18 Tr. 334) and, in view of

the testimony of Superintendent Drachler and Member McDonald

(based on past experience with open enrollment ), that such a

policy would at best result in one-way integration. The

court apparently perceived the defect: (question to Dr. Drach

ler) "As I understand it, you have misgivings about the effect

or about Plan A, bringing about integration in terms of white

students moving into black schools, predominantly black

schools" (11/18 Tr. 291). Cf. Green v. County School Bd. of

New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430, 441-42 (196*8).

-17-

Board Member McDonald was one of the two Board members who

voted against the April 7, 1970 plan of desegregation (the

other being current Board President Hathaway)(A. 83, 87). As

the defendant Board states in its Answer to the Complaint,

'as recently as April 14, 1970 • • • Member Patrick A. McDonald

formally introduced a 'magnet' plan to the Detroit Board of

Education . . . " (A. 113). (The plan itself is attached to

defendants' Answer as Exhibit 2, A. 118). This "magnet"

plan was introduced by McDonald as an alternative to the April

7 plan (ll/l8 Tr. 30, 36-37)* but was tabled by vote of the

Board on April 14, 1970 (11/18 Tr. 32-33)

B. The Campbell Plan

The district court referred to the Campbell Plan

as follows (A. ):

/ For the purposes of our present ruling we

/ consider the Campbell, or "Magnet Curriculum"

1 Plan, albeit perhaps an "exciting concept of

1 secondary education," as one which does not *

lend itself to early implementation because

of the programming and operational difficulties

which attend it. It is a distinctive departure

from past and present practices, and lacks a

background of experience. The most obvious

question mark concerning it is its impact upon

21/ The "magnet" plan which was rejected on April 14, 1970 is

like the plan approved below, with the exceptions that it

involved 5 geographic areas rather than the present 4, and it

did not contain the "middle school" (see n. 22 infra) and "open

enrollment" aspects of the present plan (11/18 TrT"31, 34-35).

22/ In addition to magnet high schools and open enrollment, the

McDonald Plan also contains a "middle school" proposal to

create one school in each of the eight regions housing the fifth

sixth, seventh and eighth grades. Enrollment would be limited

to 500 in each of the schools, and each would have a controlled

racial quota 50$ black and 50$ white. Admission "would be on

a voluntary basis and would necessitate application by inter

ested parents" (A. 27 ; 11/18 Tr. 12-14).

the achievement of identity. It is best

viewed as an educational concept meriting

study by our educators.’ i ■

The Campbell Plan (A. 36 - 39) is to some extent. . . j . . ..

similar to the McDonald Plan in that it provides that certain

high schools would offer specialized curricular

C. Staff Proposals

At least three other proposals for desegregation

originated within the administrative staff, and one was

23/ The difference between the Campbell Plan and the McDonald

Plan lies in the proposal that a student would attend his

base, attendance area high school for approximately one-half

of his courses, those being the courses which are required for

graduation. In addition, a student would participate in stu

dent activities, athletics, student government and graduation

ceremonies at his base high school (11/18 Tr. 74). The

remaining one-half of his studies would be electives and might

require attendance at another school. If his base school was

the locale of the electives he chose, he would remain there.

Some testimony indicated that some method could be devised to

eliminate this problem (11/18 Tr. 74, 80-81). The plan would

be effectuated by providing a series of free shuttle buses to

take students between schools (11/18 Tr. 78)• The premise,

in the written plan submitted to the court, is that since stu

dents would be able to take certain non-required courses in

other schools, all required courses would continue to be pro

vided at each base school.

The Campbell Plan has not been "fleshed out" in detail (11/18

Tr. 84), but one of its problems at this stage of development

is that required courses predominate in the first and second

years of the high school curriculum while electives are generally

taken in the junior and senior years (11/18 Tr. 144). Much of

the operation of the plan, insofar as integration is concerned,

depends on the selection of course offerings by the students

(11/18 Tr. 95-96); the plan too easily lends itself to classroom

and curriculum segregation. (See 11/18 Tr. 92-95).

24/ The Board also considered and rejected two other proposals

proffered by members: an open enrollment plan suggested by

Board member Mogk (11/18 Tr. 182) and a different "magnet" plan

offered by member McDonald himself (11/18 Tr. 189-90)*

presented to the Board of Education. The proposals contained. '■ ■

alternatives but basic to each one was February 1 implementa

tion of the April 7# 1970 plan as the starting point for

25/further desegregation.— '

25/ One of the rejected alternatives was a November 9 staff

task force "Proposal for School Desegregation" which had

been presented to the Board by Dr. Freeman Flynn (11/18 Tr.

187-88). (Plaintiffs' Exhibit 13, A. 123). There are three

aspects to this proposal: (1) implementing the April 7 plan

as it affects those students entering school on February 1,

1971; (2 ) reorganizing the grade structure on a 4-4-4, rather

than 6-3-3, basis "(a)s part of a long-range plan to provide

further desegregation . . . " (A. 123)(in essence, this is a

pairing proposal); (3) refining and expanding the magnet

school approach (A. 123) by "clos(ing), as regular Junior or

senior high schools, those schools with seriously declining

enrollments, and reorganiz(ing) them as specialized schools

or as experimental 'open' schools with a city-wide enrollment"

(A. 124)(11/18 Tr. 265-68). In contrast to this latter pro

posal to utilize underfilled high schools to increase

desegregation, the present Board policy with regard to over

crowding — to bus students to underutilized schools so as

to increase integration at the receiving schools — is not

applied at the high school level (8/27 Tr. 153-54), despite

the existence of six inner-city black high schools which are

under capacity and six outer-city white high schools which

are over capacity. Last year, 2000 to 3000 lower grade pupils

were transported at Board expense under this policy (8/27 Tr.

153).

In addition to the staff proposal of November 9> Dr. Flynn

testified about two other desegregation proposals which were

made following this Court's October 13 opinion: one recommen

dation dated October 24, 1970 from Dr. Flynn's Department of

Intergroup Relations to its parent Division of School-Community

Relations (Plaintiffs' Exhibit 11, A. 126); and a series of

"Proposals in the Matter of School Integration" dated November

2, 1970, submitted to the dtaff task force (which subsequently

made the November 9 proposal to the Board discussed above) by

the Division of School-Community Relations (Plaintiffs' Exhibit

12, A. 130), These last two suggestions (Plaintiffs' Exhibits

11 and 12) were objected to and were not admitted into evidence

by the district court but were filed as an offer of proof

under Rule 43(c), F.R.C.P. (11/18 Tr. 265). Plaintiffs offered

these three proposals not as alternatives to the McDonald and

Campbell plans but to demonstrate the availability of more

effective techniques of desegregation. Compare Green v. County

School Bd. of New Kent County, supra, 391 U..S. at 439:

Further Continuance of the Trial on the Merits

This Court, on October 13, 1970, in refusing to

disturb the district court's denial of a preliminary injunc

tion, noted the extent of the relief requested by plaintiffs

(see note 1 supra) and the fact that the District Judge "has

advanced the case on his docket to November 2, 1970 and

allotted two weeks for the trial." Bradley v. Mllliken, supra,

slip op. at p. 14.

25/ (continued)

Of course, the availability to the board of

more promising courses of action may indicate

a lack of good faith; and at the very least it

places a heavy burden upon the board to explain

its preference for an apparently less effective

method. . . . It is incumbent upon the district

court to weigh . . . (a proposed plan) in

light of the facts at hand and in light of

any alternatives which may be shown as feasible

and more promising in their effectiveness.

The October 24 proposal by the defendant Board's Depart

ment of Intergroup Relations made four recommendations for

integrating Detroit's public schools: (l)reinstate the April

7 boundary changes on February 1, 1971 and increase the ef

fectiveness of the April 7 plan by applying it to all

incoming tenth graders and all students presently enrolled in

the tenth and eleventh grades; (2 ) pair certain junior high

schools; (3) close certain inner-city junior and senior high

schools with declining enrollments and reorganize them as

specialized or "open" schools together with a magnet concept;

(4) transport students as in Berkeley, California to achieve

a structured student racial ratio at each school in the

system of at least 40$ minority race students (A. 126-129;

11/18 Tr. 249-52, 258-62).

The November 2, 1970 submission by the Division of School-

Community Relations to the staff task force contained five

alternative suggestions: (1) implement the April 7 plan on

February 1, 1971; (2) increase the scope of the April 7 plan by

making it effective as to eleventh graders, as well as current

and incoming tenth graders; (3) pair certain junior high and

elementary schools with less than 5$ of either white or black

students (the proposal notes that there are currently "(t)hirty nine elementary schools (which) have less than 5# black

students and 94 schools have less than 5# white students" (A.

Following this Court's remand on October 13, 1970,

plaintiffs, in an effort to avoid confusing the issues sur

rounding the April 7 plan and §12 of Act 48 with the issues

involved in the trial on the merits, filed a limited motion

to require the Detroit Board to implement the April 7 plan.

On November 4, 1970, the scheduled trial date, the district

court sua sponte continued the trial on the merits to December

8, 1970* and conducted a separate hearing on plaintiffs'

26/motion to implement the April 7 plan.—

During the course of the latest hearing, which

commenced on November 18, the defendant Detroit Board on

November 19 filed a motion to continue the trial on the merits

"from December 8, 1970, to a date certain on or after Monday,

January 18, 1971" (A. 40 ). As grounds for the motion, the

defendant Board set forth four reasons: (l) "Plaintiffs'

counsel has estimated that presentation of his proofs will

25/ (continued) 132)); (4) utilize a magnet concept by

reorganizing inner-city schools with declining enrollments

(5) cross-bus as in Berkeley, California "for a structured student ratio" (A. 134; 11/18 Tr. 263-64). .

The Division's report to the task force notes one

disadvantage of the magnet concept — "integration of students

will not immediately result from the magnet school concept.

The city-wide attraction to both white and black parents is

a function of sufficient time to 'prove' to the community

the educational strength and the merit of the specialized

magnet schools" (A. 134).

26/ As previously noted (n. 6 supra), plaintiffs assented to

tnis procedure on the condition that the district court set

a definite December trial date, as plaintiffs had gone to

considerable trial preparation, scheduled the appearance of

numerous witnesses, and desired a speedy determination of their

rights.

and "Defendants*

proofs will require a minimum of two weeks" which would cause

interruption of the trial by the holidays; (2) the Detroit

Board is in the process of administrative decentralization

pursuant to Act 48; (3) ten new Board members would be taking

office on January 1, 1971, and it would "be a severe denial

of due process" not to give the incoming board "full opportunity

to have actively participated in the trial on the merits"

should the court order any relief; (4) the trial on the

merits should await action by the Supreme Court on scnool

desegregation matters now pending before it (A. 40 - 43).

In its "Ruling on Motion for Continuance" the

district court granted the Detroit Board's motion, stating as

its reasons: (1) commencing trial on December 8 "would

result in fragmentation of the proceedings because of the

impending holidays"; (2) the Detroit Board was engaged in

preparation for administrative decentralization to take effect

■ on January 1, 1971; (3) "it would be grossly unfair to the new

central Board of thirteen members, only three of whom would be

carry-overs, not to allow them time in which to warm their

chairs and prepare for their participation in the trial on

the merits"; (4) "there is a possibility that decisions in

cases now before the Supreme Court of the United States

27/ This same estimate was given to the court on November 4,

1970, at which time it selected the December 8 trial date.

require eight to twelve trial days"'

will be forthcoming In the near future, and they may well

affect the format and trial of this cause"; (5) that the

Court's ruling on plaintiffs' motion to implement the April

7 plan had resolved "the most urgent issue in the case" (A.100-0 1).

Plaintiffs were subsequently advised in Chambers

that the district court would not schedule the trial on the

merits to commence until some time in late March or April.

1

:

it

Jf-[

■24

ARGUMENT

"THE COURT: ... Naturally, but for the

legislative action and the recall move

ment, the April 7 plan would have been

fully implemented this fall, would it not?

A [Superintendent Drachler] Yes, sir."

(11/4 Tr. 33).

.

.

!

—25”

Introduction

Before embarking upon an analysis of plaintiffs’

position and the opinion of the court below, it seems

pertinent to summarize, stripped of legal formalism, what

has happened to the rights of Negro plaintiffs in the

context of this case.

On April 7, 1970, the Detroit Board of Education

as then constituted adopted a plan of desegregation designed,

in the words of former Board President Rev. Darneau L.

Stewart, to correct the effects of the racial discriminatory

policies of the past: "This Board in past years helped to

. . . I

perpetuate segregation and must now undo the wrongs of the

past" (8/27 Tr. 327-28). The plan adopted was a simple

pairing plan. It paired predominantly white high schools

with predominantly black high schools merely by redrawing

the attendance boundaries for the schools in an east-west

rather than north-south direction. By so redrawing the

boundaries, because of the pattern of racial containment in

Detroit, substantial numbers of black and white children

would be included in each high school.

. ‘ •

The plan was a "modest" one (11/18 Tr. 253),

but in the words of Superintendent Drachler, "(w)ithout

it each constellation (high school attendance area and

feeder schools) will continue a growing pattern of segregated

racial or economic enclaves . . . " (quoted in Bradley v.

Mllllken, supra, slip op. at p. 4).

This modest effort at desegregation was met, however

by a massive outpouring of white community hostility, racial

fear and general furor in Detroit (E.g., 11/18 Tr. 160). The

four School Board members who voted in favor of the April 7

plan were recalled by Detroit's 6o$-white electorate;^1'

the Michigan Legislature passed Section 12 of Act 48 which

purposefully nullified the April 7 plan. To black parents

in Detroit, the lesson of 812 and the recall movement was

crystal clear: the schools which their children must attend

would remain segregated so long as a majority-white Legis

lature and a majority-white electorate could so maintain

them.

t. - ' • SSKft -i

In this situation, as Dr. Golightly said (11/18

Tr. 171), "since as a minority they (black people) could

not win politically they need to have the support of the

courts." Yet plaintiffs return to this Court four months

after the filing of this lawsuit, after three extensive

hearings and one earlier reversal by this Court of a district

court ruling, because black plaintiffs and parents in Detroit

have been told that desegregation under the effective and

simple April 7 plan need not occur precisely because of

the same hostility to desegregation which spawned the recall

movement and §12 of Act 48 itself.

28/ Although Detroit's public school enrollment is 65# black,

its voters are 60# white (11/18 Tr. l6l).

, The District Court's Postponement

Of Relief Until September, 1971

Denies Plaintiffs' Constitutional

Rights In Direct Violation Of The Rule Of

Alexander v. Holmes County Board

of Education and Carter v. West

Feliciana Parish School Board

The Fourteenth Amendment rights which plaintiffs-

appellants assert in the present litigation "are, like all

such rights, present rights; they are not merely hopes to some

future enjoyment of some formalistic constitutional promise.

The basic guarantees of our Constitution are warrants for the

here and now, and, unless there is an overwhelmingly

compelling reason, they are to be promptly fulfilled." Watson

v. City of Memphis, 373 U.S. 526, 533 (1963)(emphasis in

original). "(A)ny deprivation of constitutional rights calls

for prompt rectification." Id. at 532-33.

In its October 13, 1970 opinion in this case,

this Court held that the State of Michigan, through legislative

enactment, had deprived plaintiffs of their Fourteenth Amend

ment rights. The Court said: "The tenth grade students who

would have attended a high school with an improved racial

balance as determined by the Board of Education on April 7 have

been deprived of that opportunity from the beginning of the

1970-71 school year until the time of the rendering of this

opinion." Bradley v. Mllliken, Bupra, slip op. at p. 8.

I

-28

The order now appealed from, postponing any relief'

until September, 1971# deprives the Detroit students whom

this Court found had been denied their constitutional rights

by action of the Michigan Legislature of any opportunity to

enjoy their rights as tenth grade students.

Alexander v. Holmes County Bd. of Educ., 396 U.S.

19 (1969) commands that deprivations of the Fourteenth Amend

ment right to equal educational opportunity be vindicated

"at once"; the certainty of that command was made indelible

in Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Bd., 396 U.S. 226

(1969)(injunction pending certiorari), 396 U.S. 290 (1970)

29/(per curiam reversal of delay).— '

29/ Following Alexander, the Fifth Circuit delayed pupil

integration3n sixteen school districts until September,

1970. Pending action on the petition for certiorari in

Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Bd., the Supreme Court

entered an order (396 U.S. 22b (December 13, 1969)) requiring

the school boards, pendente lite, to "take such preliminary

steps as may be necessary to prepare for complete student '

desegregation by February 1, 1970." Following the Supreme

Court's interim order in Carter, the Fifth Circuit, ruling on

motions for summary reversal, for injunctions pending appeal

and on petitions to recall and amend mandates, ordered school

districts to take all steps preliminary and preparatory to

second-semester implementation of complete pupil desegregation

plans. Baird v. Benton County Bd. of Educ., 421 F.2d 700 (5th

Cir. 1970); galley v. Rapides Parish School Bd., 422 F.2d 814

(5th Cir. 1970); United State's v. Greenwood Municipal Separate

School Dist., 422 F.2d I250 (5th Cir. 1970); Hilson v. Ouzts,

421 F.2d 632 (5th Cir. 1970); Jones v. Caddo Farish SchooT'Bd.,

421 F.2d 313 (5th Cir. 1970); Boykins v. Fairfield Bd. of Educ.,

421 F.2d 1330 (5th Cir. 1970); Williams v. Iberville Parish

School Bd., 421 F.2d l6l (5th Cir'. 1970); Charles v. Ascension Parish School Bd., 421 F.2d 656 (5th Cir. 1970); Williams v.

Kimbrough"," 421" F.2d 1351 (5th Cir. 1970). On January" 14"“ 1970,

the Supreme Court entered its per curiam opinion in Carter

(396 U.S. 290), reversing the Fifth Circuit insofar as it had

delayed complete student desegregation for one semester. It

was now crystal clear to all that the "at once" command of

-29-

In Christian v. Board of Educ. of Strong School

Dist. No. 83, No. 20038 (8th Cir., December 8, 1969), the

.

Eighth Circuit entered an order summarily reversing a

district court's one-year delay in desegregating a school

system which had come under court order for the first time

(p. 2):

Upon review of the abbreviated record before

us it is clear that the district has not

taken steps to effectively implement a

desegregated unitary school system and is

operating contrary to law and the Constitution

of the United States. The only defense pre

sented is that this is the first time the

district has been compelled to act by court

decree and that it would be impractical and

detrimental to the educational process to

. require immediate desegregation. These

claims can no longer serve as deterrents to

immediate compliance with the law. Alexander

v. Holmes, supra. It has long been incumbent

upon the school boards to voluntarily accom

plish an end to segregation without judicial

prodding. See Brown v. Board of Educ., 347

U.S. 483 (1954)1 (emphasis in original)

29/ (continued) Alexander meant exactly what it said. In

Stanley v. Darlington County School Dlst., 424 F.2d 195,

196 (4th Cir. 1970)1 Chief Judge Haynsworth,on the basis

of Alexander and Carter, ordered mid-year "reassignment of

58,00u pupils and their teachers"(424 F.2d at 197;* noting that

These decisions leave us with no discretion

to consider delays in pupil integration

until September 1970. Whatever the state

of progress in a particular school district

and whatever the disruption which will be

occasioned by the immediate reassignment

of teachers and pupils in mid-year, there

remains no judicial discretion to postpone

immediate implementation of the constitu

tional principles as announced in Green

. . . Alexander . . . Carter . . . .

The same arguments which were urged upon the Eighth

Circuit in the Strong case were pressed upon the court

below; indeed, those very same reasons for deferring the

enjoyment of plaintiffs' constitutional rights were argued

to this Court in October. But the response of this Court can

be no different from that of the Fourth, Fifth and Eighth

30/Circuits;,— 1 the constitutional rights involved are those

guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment — the remedy must be

I ■accorded "at once."

Despite the district court's attempted distinction

(A. 97), Alexander and Carter do apply to this case Just as

jthis Court held in October that the principles announced in

• I . . . • !other school desegregation cases applied in determining the

constitutionality of §12 of Act 48 (Bradley v. Mllllken,

supra, slip op. at pp. 10-1 1 ); and the order below must be

reversed because it fails utterly to provide a timely remedy

for the deprivation of constitutional rights.

30/ Since the Supreme Court’s command in Alexander (with the

emphasis added by Carter), the federal courts have not

hesitated to carry out the mandate in mid-year and often in

mid-semester. See^ e.g., Stanley v. Darlington County School

Plat., supra (discussed in note 29 supra); United States v.

Hinds County School Bd., 423 F.2d 1264, 1268 T5!H Cir. I969)

(implementing the Supreme Court's decision in Alexander by

ordering mid-year "transfer of thousands of schoolchildren and

hundreds of faculty members to new schools"); Nesbit v.

Statesville City Bd. of Educ., 4l8 F.2d 1040 ('4't'h""Ci'r. 1969)

(en banc)"; United States v. Board of Educ. of Baldwin County,

423" f72cT 10T3 (^th Cir .' 1970) (mid-semester) ; Christian v.

Board of Educ. of Strong School Dist. No. 83, supra. In a

pre-Alexander case, the Eighth Circuit sitting en banc ordered

a complete desegregation plan fully implemented-!)/ the start

of the^second semester. Jackson v. Marvell School Dist. No.

22, 4l6 F.2d 380 (8th Cir. 1969)(en banc)'.

II

The District Court Erred In Approving

A "Free Choice" Plan Despite Compelling

Evidence That The Technique Had Never

Worked In Detroit, And In Basing That

Approval On The Ground Of White Community

Hostility To Other, More Effective Means

Of Desegregation

Aside from the patently impermissible delay, the

district court has erred substantively by ordering into

September, 1971 effect a plan of high school organization

which in effect has no relationship to plaintiffs' Fourteenth

Amendment rights.

The district court makes the following findings:

1. "(W)e have in Detroit a community (society)

generally divided by racial lines" (A. 92).

2. "A good education, to say nothing of the best

education, cannot be achieved without integration" (A. 92).

3. The April 7 plan's "principal aim is to improve

integration by the 'numbers' . . (A. 94).

4. "(W)here a school district has taken steps

enhancing integration in its schools it may not reverse

direction. In the setting of our case nonaction is (or amounts

to) prohibited action . . . (A)ny action or failure to act

by the Board of Education designed in effect to 'delay,

obstruct or nullify' the previous (April 7th) step toward

improving racial balance in the Detroit schools is prohibited

State action" (A. 98).

-32-

In the face of these conclusions and this Court's

opinion, the district court has denied plaintiffs' motion

to adopt "the best available plan" in the record^/ (United

States v. Board of Educ. of Baldwin County, supra) which

will effectively integrate a "number" of black and white

children in the Detroit public schools pending the trial

on the merits at which a more comprehensive desegregation

plan for all schools may be ordered. In doing so, the court

has permitted a reversal of direction by the Detroit Board,

i.e., from a pairing plan of desegregation with the pupil

assignments by the Board to a "free choice" or "magnet school"

plan effective not September, 1970 or February 1, 1971 but

"delayed" until September, 1971*

The McDonald Plan is but "freedom of choice" (South)

gone North ("open enrollment"); the McDonald open enrollment

concept has already proved itself to be as ineffective in

32/Detroit as "free choice" has been in the South.— ' The

31/ The district court is simply incorrect, however, when it

states: "it is plaintiffs' view, as we understand it,

that the Court is limited to considering only the April Plan

at this time" (A. 93). Plaintiffs initially opposed a

hearing on the two alternative plans because on their face,

they did not promise as much integration as the April 7 plan

as required by the district court's November 6 order (ll/l8 Tr

4-5). And in closing argument, in response to a direct ques

tion by the court, plaintiffs' counsel stated that the Court

was not limited to consideration of the April 7 plan but

that the McDonald and Campbell plans were simply inadequate.

(11/18 Tr. 335-36). Cf. Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, Denver,

303 F. Supp. 289, 296T5. Colo." 1969)'. *

32/ No "free choice" or "free transfer" plan has been approved

in any reported post-Green decision of which plaintiffs

are aware; such plans have teen rejected in numerous decisions

of federal courts. See, e.g., Steele v. Board of Public

Instruction of Leon County, 421 F.2d 1382 (5th 6ir. I969)S

Detroit experience with past "open enrollment" programs

portends the failure of the McDonald Plan. Prior to 1966,

the Detroit Board operated an open enrollment policy which

provided that any pupil in the system could transfer to

certain under-capacity schools which were listed as "open

schools" each semester (8/27 Tr. 63-64). Because the policy

operated in a manner adverse to integration, it was modified

in 1966 by adding the qualification that a student could

transfer to an "open school" only if his entry into that

school would enhance integration. But, even with this

qualification, as both the Superintendent and Member McDonald

admitted, the policy resulted in a few blacks exercising the

option to go to white schools, but no whites exercising

the option in reverse (8/27 Tr. 53; 11/18 Tr. 17, 290, 291,

315).

The McDonald Plan, in contrast to the April 7

plan of two-way integration, will thus operate "simply to

32/ (continued) United States v. Greenwood Municipal

Separate School Dlst., 422 F.2d I250 (5th Cir. 1970);

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dlst., 419

F.2d 1211 (5th Cir. 1969), rev'd on other grounds sub nom.

Carter v. West Feliciana Parish ScTTool B~3Y, 396 U.S. 2$0

(1970); Lemon v. Bossier Parish School Bd., 421 F.2d 121

(5th Cir. 1970); Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Bd., 417

F.2d 801 (5th Cir. 1969)(38 school districts); United States

v. Hinds County School Bd., 417 F.2d 852 (5th Cir.' "l'$6$) ('33”

school districts); Anthony v. Marshall County Bd. of Educ.,

409 F.2d 1287 (5th Cir. 1969); Walker v. County School Bd.

of Brunswick County, 413 F.2d 53 (4th Cir. 1970); Jackson,

v. Marvell School Dlst. No. 22, 4l6 F.2d 380 (8th Cir. 1969) (en banc). ' — — — —

burden children and their parents with the responsibility

which Brown II placed squarely on the School Board." Green

v. County School Bd, of New Kent County, supra, 391 U.S. at

441-42.

Conclusive evidence of the ineffectiveness of the

McDonald Plan appears in past efforts by the Detroit Board

to duplicate the integration which has occurred at Cass

Technical High School,— ^ relied on so heavily by the district

court and the plan itself. This effort, known as "Project

One," arose out of concern by the Board in 1965 or 1966 that

three of its high schools were becoming increasingly black

in student enrollment. In an effort to stabilize the racial

balance by attracting and retaining white students, the Board

concentrated its specialized Science and Arts program in these

three high schools and spent $1 million a year trying to

implement the thesis of the McDonald Plan. Superintendent

Drachler testified that the project was abandoned last year

as a total failure (11/18 Tr. 293-94) .

33/ Cass Tech is a non-attendance-area high school in the

Detroit School System which draws its pupil enrollment on

a city-wide basis. (8/27 Tr. 53). Cass Tech is 60.9% black,

enrolling 4,302 students (Plaintiffs' Exhibit 10). Cass Tech

is utilized as a college preparatory school and accepts for

admission only those public school children who graduate from

junior high school with a minimum B average; because of this

selectivity, it has a reputation for academic excellence which

makes it attractive to all parents in the City of Detroit (11/18

Tr. 56), demonstrated by its highest mean scores on tenth and

twelfth grade achievement tests of any other high school (Plain-

tiffs| Exhibit 9A, p. 28; A. 107). Because of its academic

superiority Cass is able to draw from the other high schools

in the City of Detroit the most qualified students and also,

apparently, most of the better qualified white students who

desire an integrated education. Cass Tech is distinguishable

from the McDonald Plan since the latter does not (and could not)

limit admission to academically superior students and it will

not attempt to draw on a city-wide basis; rather, each high

school will attempt to draw students from two regions, one

black and one white. (See A. 34-35).

-35-

Further, this same "magnet" plan was presented

to the April 7 Board by Mr. McDonald in the first attempt

to halt the desegregation effected by the April 7 plan, but

it was rejected by that Board on April 14, 1970 (see page

18 supra). The next attempt to nullify the April 7 plan

came in the form of §12 of Act 48 wherein the Michigan

Legislature commanded the Detroit Board to operate on a

"free choice" basis "but providing priority acceptance . . .

to those students residing nearest the school and to those

students desiring to attend the school for participation in

vocationally oriented courses or other specialized curriculum.

Bradley v. Mllllken, supra, slip op. at p. 23. The "special

ized curriculum" exception in the Section was added by the

Legislature as a result of Board Member McDonald’s efforts

to obtain legislative sanction for his "magnet" plan which

had been rejected by the Board on April 14, 1970 (11/18 Tr.

37).

This Court held §12 unconstitutional on October 13,

1970. Yet, §12 survives in the form of the district court’s

order as effectively as if this Court had never spoken. The

majority of the current Board do not believe that the McDonald

Plan will result in integration,iLi/ and the district court

35/itself has serious reservations.— •

34/ See note 19, supra.

35/ "That it will promote integration to the extent projected

remains to be seen . . . " (A. 95 )• McDonald himself

admitted that a valid projection could not be made (11/18 Tr.

203).

In contrast to the demonstrated ineffectiveness

of the McDonald Plan, the professional staff^^ and two

Board members with backgrounds in educationr^ urged the

38/April 7 plan.

In a community "generally divided by racial lines"

the adoption by the school board and approval by the court of

previously used and ineffective techniques for desegregating

or improving the racial balance of Detroit’s public schools

does not accord plaintiffs their constitutional rights. This

Court, noting that "the April 7 plan came into being . . . by

the voluntary action of the Detroit Board of Education in its

effort further to implement the mandate of the Supreme Court

in Brown . . . and succeeding cases, such as Alexander . . .

and Green • . ." (slip op. at pp. 9-10), held that the tenth

grade students in the twelve April 7 high schools have been

deprived of.their constitutional rights by §12 of Act 48.

Those students and others similarly affected and to be affected

are clearly entitled to a remedy for the wrong done them by

----------------------------- ; . • .

36/ See pages 19-20, supra, and note 25, supra.

37/ See note 15, supra.

38/ Dr. Golightly testified (11/18 Tr. 156-57, 158-59):

"(T)here is something fundamentally good about

integrated education, or desegre^ed education,

even if it merely means having in the classroom

a black person and a white person together. . . .

If the issue is integration the simplest way to

integrate a school system is to irtegrate it. I

feel that in terms of the plans presented it

(April 7 plan) is simple, straightforward,

involves established and proven ways in which

you would Integrate, you start out with elementary

j schools that feed into junior high schools and

-37

•I

7>rI

Act 48. On remand, the lower court's obligation was to

assess available methods of operating the Detroit public

'Kt

schools according to accepted judicial standards to determine

what method would best vindicate the rights of plaintiffs.

The McDonald Plan should have thereby been rejected, for

"if there are reasonably available other ways, such for

illustration as zoning (e.g., the April 7 plan) . . .

'freedom of choice' must be held unacceptable." Green v.

County School Bd« of New Kent County, supra, 391 U.S. at 441.

Yet even a hurried reading of the district court's

"Ruling on School Plans Submitted" reveals that the court has

substituted its own educational theories for constitutional

principles, and has dignified in a most unseemly manner the

white hostility to desegregation which led to Act 48, the

recall election, and the submission by the new Board of "free

choice" plans by finding in that very hostility a justification

for less effective means of desegregation than the April 7,

1970 plan.

The district court did not weigh the plans before

it according to the result-oriented test of Green v. County

School Bd. of New Kent County, supra; it did not implement

the rule of Alexander v. Holmes County Bd. of Educ., supra

■ ■

38/ (continued)

junior high schools that feed into senior high

schools. Now the April 7 plan was not as compre

hensive as that. I understand they merely wished