LDF Moves to Head Off Government Delay in Georgia School Integration

Press Release

September 6, 1969

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 6. LDF Moves to Head Off Government Delay in Georgia School Integration, 1969. d21e69b4-b992-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/bd674988-286b-4883-8524-af134a6a9510/ldf-moves-to-head-off-government-delay-in-georgia-school-integration. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

fo

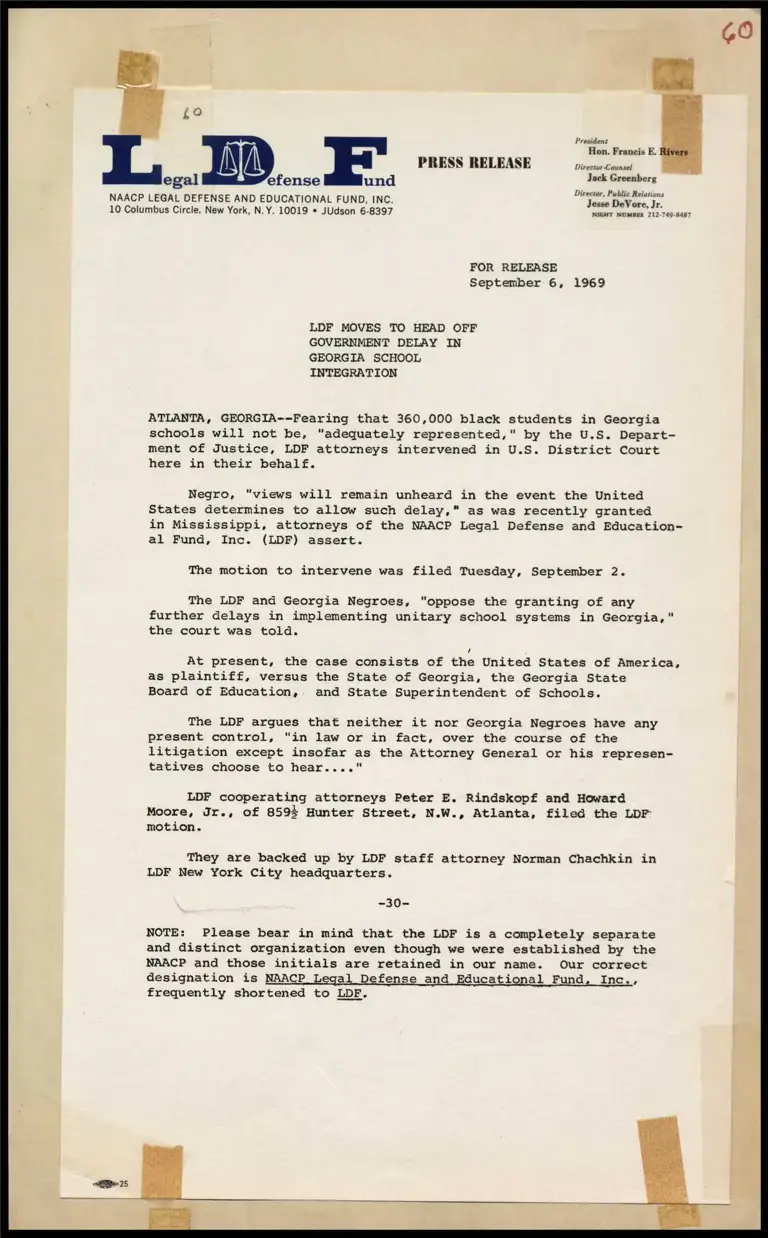

President

Hon. Francis E.

PRESS RELEASE Director Counsel

egal efense und si Sater’

Director, ic Hons NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC. brag

10 Columbus Circle, New York, N.Y. 10019 * JUdson 6-8397 NIGHT NUMBER 212-749-8487

S25

FOR RELEASE

September 6, 1969

LDF MOVES TO HEAD OFF

GOVERNMENT DELAY IN

GEORGIA SCHOOL

INTEGRATION

ATLANTA, GEORGIA--Fearing that 360,000 black students in Georgia

schools will not be, “adequately represented," by the U.S. Depart-

ment of Justice, LDF attorneys intervened in U.S. District Court

here in their behalf.

Negro, "views will remain unheard in the event the United

States determines to allow such delay," as was recently granted

in Mississippi, attorneys of the NAACP Legal Defense and Education-

al Fund, Inc. (LDF) assert.

The motion to intervene was filed Tuesday, September 2.

The LDF and Georgia Negroes, “oppose the granting of any

further delays in implementing unitary school systems in Georgia,"

the court was told.

,

At present, the case consists of the United States of America,

as plaintiff, versus the State of Georgia, the Georgia State

Board of Education, and State Superintendent of Schools.

The LDF argues that neither it nor Georgia Negroes have any

present control, “in law or in fact, over the course of the

litigation except insofar as the Attorney General or his represen-

tatives choose to hear...."

LDF cooperating attorneys Peter E. Rindskopf and Howard

Moore, Jr., of 8594 Hunter Street, N.W., Atlanta, filed the LDF

motion.

They are backed up by LDF staff attorney Norman Chachkin in

LDF New York City headquarters.

=30=

NOTE: Please bear in mind that the LDF is a completely separate

and distinct organization even though we were established by the

NAACP and those initials are retained in our name. Our correct

designation is NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.,

frequently shortened to LDF.

GO