Patterson v. Newspaper and Mail Deliverers' Union of New York and Vicinity Brief of Defendant-Appellee

Public Court Documents

September 19, 1974

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Patterson v. Newspaper and Mail Deliverers' Union of New York and Vicinity Brief of Defendant-Appellee, 1974. 1d6757e3-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/bd7f3bea-0776-40f0-8f52-d56f8b5e9e15/patterson-v-newspaper-and-mail-deliverers-union-of-new-york-and-vicinity-brief-of-defendant-appellee. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

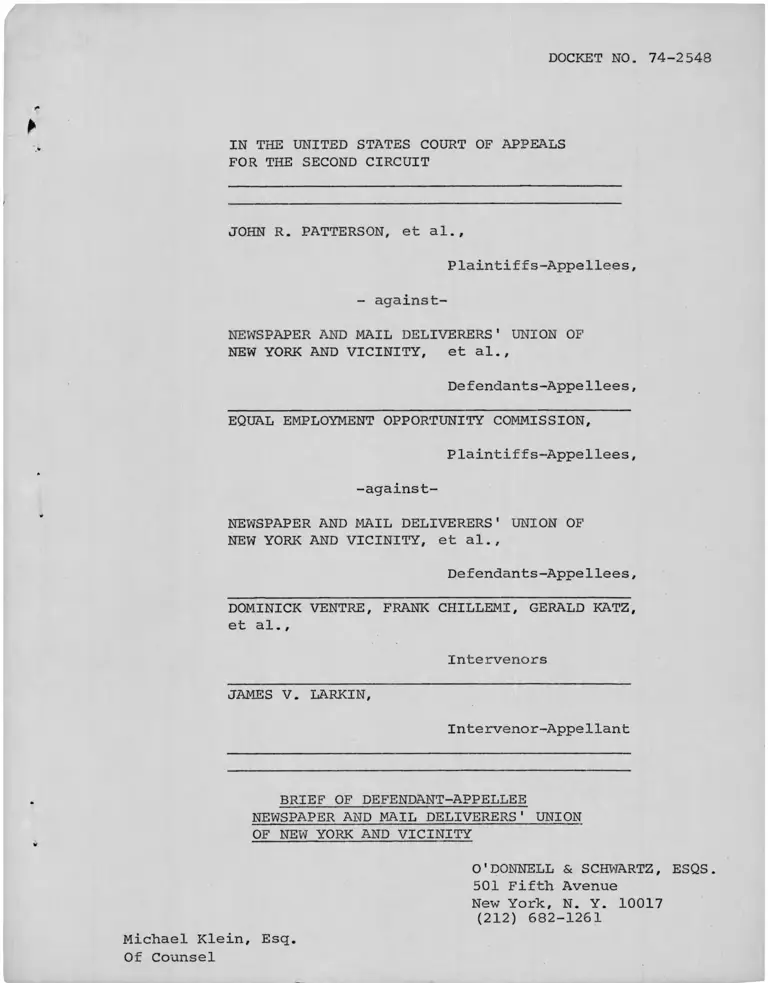

DOCKET NO. 74-2548

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

JOHN R. PATTERSON, et al.f

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

- against-

NEWSPAPER AND MAIL DELIVERERS' UNION OF

NEW YORK AND VICINITY, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees,

EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY COMMISSION,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

-against-

NEWSPAPER AND MAIL DELIVERERS' UNION OF

NEW YORK AND VICINITY, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees,

DOMINICK VENTRE, FRANK CHILLEMI, GERALD KATZ,

et al.,

Intervenors

JAMES V. LARKIN,

Intervenor-Appellant

BRIEF OF DEFENDANT-APPELLEE

NEWSPAPER AND MAIL DELIVERERS' UNION

OF NEW YORK AND VICINITY

O'DONNELL & SCHWARTZ, ESQS.

501 Fifth Avenue

New York, N. Y. 10017 (212) 682-1261

Michael Klein, Esq.

Of Counsel

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

ARGUMENT:

The Approval By The Court Below Of The

Settlement Agreement Was In Accordance

With The Requirements And Objectives Of

Title VII Of The Civil Rights Act

CONCLUSION

TABLE OF CASES CITED

PAGE NOS.

Griggs v. Duke Power Co.

401 U.S. 424 (1971) 12

Humphrey v. Moore

375 U.S. 335 (1963) 5

Rios v. Enterprise Association Steamfitters

Local 638, 501 F. 2d 408 (2nd Cir. 1973) 3, 12

Trans World Airlines, Inc. v. State Human

Rights Appeal Board, et al, N. Y. Sup. Ct.,

App. Div., 2d Dept., N. Y. Law Journal,

December 5, 1974, pp. 1, 5. 4

U. S. v. Bethlehem Steel Corp.

446 F. 2d 652 (2nd Cir. 1971) 7, 10, 12

U. S. v. Wood, Wire & Metal Lathers International

Union Local Union No. 46

471 F. 2d 408 (2nd Cir. 1973) 3, 7, 12

STATUTES

Civil Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. 2000(e) et seq. 1,2,6,8,10,11

Labor-Management Relations Act

29 U.S.C. 141 et seq. 5, 6.

DOCKET NO. 74-2548

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

JOHN R. PATTERSON, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

-against-

NEWSPAPER AND MAIL DELIVERERS' UNION OF

NEW YORK AND VICINITY, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees,

EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY COMMISSION,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

-against-

NEWSPAPER AND MAIL DELIVERERS' UNION OF

NEW YORK AND VICINITY, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees,

DOMINICK VENTRE, FRANK CHILLEMI, GERALD KATZ,

et al.,

Intervenors

JAMES V. LARKIN,

Intervenor-Appellant

BRIEF OF DEFENDANT-APPELLEE

NEWSPAPER AND MAIL DELIVERERS' UNION

OF NEW YORK AND VICINITY

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

This is an appeal by one of the intervenors, Larkin,

in which he seeks to reverse an Opinion and Order rendered on

September 19, 1974, by United States District Court Judge

Lawrence W. Pierce in the United States District Court for the

Southern District of New York. In his aforesaid Opinion and

Order, Judge Pierce had approved a settlement agreement dated

June 27, 1974, in which the plaintiffs, the Defendant Union and

the Defendant Employers had all joined and which settled two con

solidated actions brought by a class of private plaintiffs and

by the United States Attorney for the Southern District of New

York on behalf of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission,

(hereinafter "EEOC"), pursuant to Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act (42 U.S.C. §2000 (e) , et seq.)

Since the essential facts and background of events

leading up to the settlement agreement are adequately stated in

Judge Pierce's Opinion and Order dated September 19, 1974 and in

the brief submitted to this Court on behalf of EEOC, it is not

necessary to burden the Court with a repetitious recital of such

facts and chronology. Sufficient it is to confine this brief to

a rebuttal of the contentions made by Appellant Larkin in his

brief.

ARGUMENT

It is the fundamental contention of the Defendant-

Appellee Union that the approval by Judge Pierce in the Court

below of the settlement agreement was proper in all respects,

in accordance with the requirements and objectives of Title VII

of the Civil Rights Act, and should accordingly be affirmed.

Conversely, if the settlement agreement is set aside, serious

disruption could again affect the industry which is now returning

to a state of stability following many months of unsettled labor

conditions during the pendency of the Title VII litigation.

As noted by Judge Pierce in his Opinion , the settle

ment agreement now under attack by Intervenor Larkin was reached

by the parties after a four-week trial on the merits of the two

consolidated actions. It was preceded by many months of frequent,

intensive negotiations and discussions by and among the various

parties. Indeed, an earlier tentative settlement agreement had

been rejected by a vote of the Union's membership. Following

the trial, the present settlement agreement was ratified by the

Union membership in a secret ballot.

Prior to his approval of the settlement agreement.

Judge Pierce held a hearing on its fairness, adequacy and reason

ableness after due notice to the class of plaintiffs noticed

-2-

in this law suit. On that same date, he also held a hearing

on the legality of the relief provided in the settlement agree

ment with regard to its impact on the intervenors, including

Larkin, all of whom are non-minority "shapers" in the industry.

His Opinion reflects that he gave careful consideration to each

and every contention raised by Larkin on this appeal - and he

properly rejected each such contention.

After noting that the instant settlement agreement sets

forth a goal of achieving 25% minority employment in the industry

within five years, consistent with the results in Rios v. Enterprise

Association Steamfitters Local 638, 501 F. 2d 622 (2nd Cir. 1974)

and in U. S. v. Wood, Wire and Metal Lathers International Union,

Local No. 46, 471 F. 2d 408 (2nd Cir. 1973), Judge Pierce mani

fested the thoughtful and careful consideration he gave to the

approval of the instant settlement agreement by stating:

"But, unlike Rios and Wood Wire, this settle

ment agreement does not merely commit the par

ties to the future development of a plan to

achieve that goal. Instead, it sets forth a

plan with great specificity, including varia

tions on the general theme to account for vary

ing circumstances between different employers.

Such detail indicates that the plan is the re

sult of hard, serious and good faith negotia

tions, and that the different pressures, per

spectives and interests of the parties have been

confronted and already resolved. This serves

to increase the Court's confidence that the plan

is workable, and can be implemented immediately."

-3-

1.

It is axiomatic that a settlement agreement is a com

promise involving a "give and take" process in which each party

or group settles for less than a "perfect" satisfaction or pro

tection of its respective intents. This is especially true in

seniority disputes. The chief characteristic of seniority is

that it is relative in nature. The seniority claim of any in

dividual or group necessarily affects adversely the seniority

interest of others in the bargaining unit.*

From this standpoint, none of the parties and groups

affected by the instant settlement agreement can be ideally satis

fied with all of its contents. The Defendant Union encountered

considerable difficulty in persuading its membership to accept a

settlement agreement. Certainly, the plaintiffs sought more in

the relief requested by their complaints. The various Defendant

Employers undoubtedly would have preferred less stricture and

regulation with respect to employment in their industry and they

cannot be pleased with the substantial money damages charged to

them in the Final Order and Judgment predicated on the settlement

agreement.

In this context, it is not surprising that Intervenor

Larkin is displeased with the settlement agreement. However, his

disagreement with some of its contents is not a basis for setting

* See N. Y. Law Journal, December 5, 1974, pp 1, 5, for decision

by N. Y. Supreme Court, App. Div., 2d Dept., in Trans World

Airlines, Inc, v. State Human Rights Appeals Board, et al,

which dramatically illustrates how the correction of past dis

crimination necessarily affects the seniority standing of others.

-4-

it aside. In his Opinion, Judge Pierce asserted that the

intervenors will benefit from the settlement agreement. He

described these benefits as follows:

"Most of the provisions of the settlement agree

ment are applauded by the intervenors, as well

they might be. By regulating employment oppor

tunities in the industry, unlocking Group III

and Group I, Regular Situations and Union mem

bership, the agreement will operate beneficially

for the intervenors as well as the minorities."

'There can be no dispute that the Defendant Apellee

agent of the

Union is the duly recognized/bargaining unit involved in this

litigation, including Intervenor Larkin and the other shapers he

purports to represent. In this connection, the role of the Union

in fulfilling its duty of fair representation when there are com

peting and conflicting seniority interests by members of a bar

gaining unit was settled by the United States Supreme Court in

Humphrey v. Moore, 375 U.S. 335 (1963). The action of the Union

in entering into this settlement agreement conforms to the hold

ing in Humphrey v. Moore.

2.

In substance, Intervenor Larkin is attempting improper

ly in this appeal to convert the instant Title VII law suit into

a proceeding under The Labor-Management Relations Act, 41 U.S.C.

-5-

§141, et seq, whereby individuals may invoke the unfair labor

practice procedures of the National Labor Relations Board to

remedy violations of that Act resulting from preferential em

ployment treatment accorded to employees by reason of Union

membership. In this regard, the record reflects that Intervenor

Larkin and the class of shapers he purports to represent are non

minorities (to the extent that there are minority shapers, they

are included in the class represented by the plaintiffs).

In his earlier Opinion and Order of April 30, 1974,

in which the appellant and others were permitted to intervene,

Judge Pierce strictly limited such intervention to the impact on

them of relief granted in this Title VII action involving racial

discrimination and expressly excluded any effort by intervenors

to enforce such rights as they may have under the National Labor

Relations Act for complaints of alleged discrimination on grounds

other than those authorized in Title VII. In that connection,

he chided some of the intervenors for attempting to utilize the

present Title VII proceeding to enforce an NLRB order which in

volved the Defendant Appellee Union and one of the Defendant Ap

pellee Employers and which has been affirmed by this Court in

1972.

Again, in his Opinion and Order of September 19, 1974,

Judge Pierce emphatically excluded the granting of relief to any

-6-

of the intervenors which would be based on grounds other than

discrimination within the meaning of Title VII. Thus, in reject

ing the contention raised again in this appeal by Intervenor

Larkin, Judge Pierce cogently concluded:

"Finally, it must not be forgotten that this

is a Title VII case. Such cases, as Judge

Frankel has said in Wood, Wire are 'launched by

statutory commands, rooted in deep constitu

tional purposes, to attack the scourge of ra

cial discrimination in employment . . .(a)nd

we know that, in addition to the spiritual wounds

it inflicts, such discrimination has caused mani

fold economic injuries, including drastically

higher rates of employment and privation among

racial minority groups.' United States v. Wood

Wire and Metal Lathers International Union, Local

Union 46, 341 F. Supp. 694, 699 (S.D.N.Y. 1972).

Title VII is an expression of a commitment to cor

rect minority employment discrimination and, hope

fully, the vast social consequences that flow from

it and afflict the whole of the nation. The sta

tute does not undertake to correct all forms of

employment discrimination. Thus, to the extent

that what the intervenors seek here is relief equal

to that afforded minorities, it has no legal found

ation, in this case. Under the law, relief here

must be limited to victims of the kind of discri

mination prohibited by Title VII. United States v.

Bethlehem Steel Corp., supra, 446 F. 2d at 665.

There is no evidence and no assertion that the

intervenors have been discriminated against on ac

count of race, religion, color, sex, national

origin, or because they have made charges, testified,

assisted or participated in any enforcement proceed

ings under Title VII."

3.

Repeatedly, the brief submitted on behalf of Inter

venor Larkin in this appeal erroneously informs this Court that

-7-

the Court below found that the white shapers he purports to

represent have suffered ’fequally" with minorities the effects of

past discrimination. Based on this distorted view, the appellant

inappropriately quotes the maxim that "Equality is Equity" and

pedantically cites "Pomeroy Eq. Jur. Section 405" as his autho

rity for this assertion. In effect, the appellant offers the

specious arqument that the Court below should not qrant any re

lief that did not give non-minorities equal treatment with the

minorities.

Although the Court below did acknowledge a past history

of discrimination against so-called Group III shapers on grounds

unrelated to Title VII, it is inaccurate to state that the Court

concluded that minorities and non-minorities had "suffered

equally" and therefore, that the Court had erred in not granting

"equal relief" to the appellant and to the group for x>?hich he

claims to speak.

Under the guise of seeking "equal relief", the appellant

is actually attempting to scuttle the relief accorded to minori

ties in a Title VII proceeding. Ironic, indeed, is Intervenor

Larkin's reference to the stirring words of the recent civil

rights song, "We shall overcome". Instead of "Black and white

together", he wants the minorities to march behind him on their

way to jobs in this industry!

-8-

Equally cynical and irresponsible is the appellant's

citation of sources dealing with the Nazi destruction of

European Jewry as a ground for attack on Judge Pierce's Order

approving the instant settlement agreement. Does Intervenor

Larkin dare to insinuate that Judge Pierce's decision in the

Court below can be compared to the Nazi code in dealing with the

"Jewish Question"?

The appellant's pious pretense in quoting from the

Bible is absurdly misplaced. It adds neither sanctity nor sanc

tion to his groundless argument on this appeal.

4.

In a futile attempt to bolster his untenable argument

that the settlement agreement grants proscribed "super-seniority"

to minorities which permits them to "leap-frog" illegally past

him and other Group III non-minorities, the appellant inaccu

rately ascribes the qualities of vested seniority rights of a

fUH-time employee to himself and to those in his class.

Judge Pierce expressly found that Larkin and the Group

III class to which he belongs are shapers who "do not have full

time employment, nor do many of them have any great expectations

or intention of working full-time while they shape from the

Group III list." It is common knowledge in the industry that

many of the Group III shapers hold full-time jobs in civil ser

-9-

vice and elsewhere and utilize thei.r status in this industry to

supplement their income. This is hardly the type of employment

which warrants granting them such a protected status as to shield

them from the appropriate relief available to minorities in a

Title VII action.

In commenting on a Group III shaper's work expectations

Judge Pierce made the following persuasive analysis:

"In other words, assessing a shaper's expecta

tion is a highly speculative exercise. The

Court does not mean to minimize a Group III

member's vested emotional interest in his po

sition at a shape, but it cannot be equated with

the worker who might be 'bumped' from a steady

and seemingly secure position by an outside minor

ity with less seniority than him. Further, it

must be pointed out that even if these shaping

priorities were viewed as providing firm expecta

tions, '(such) seniority advantages are not in-

defeasibly vested rights but mere expectations

from a bargaining agreement subject to modifica

tion. ' United States v. Bethlehem steel Corp.,

supra, 446 F. 2d at 663."

Moreover, Judge Pierce rejected outright the contention

of the intervenors that the settlement agreement was harmful to

them. Thus he said:

"First and dispositive of all the issues raised

by the intervenors, the settlement agreement

simply does not trample on their employment op

portunities. In the long run, it must be acknow

ledged by all concerned that the effect of this

agreement, if it operates as predicted, will be

to achieve Regular Situation or Group I status for

all members of Group III, minority and non-minority

alike, within a relatively short time span. With

out this settlement, Group III workers had little

if any hope of ever achieving either status under

the present system."

5.

After the four-week trial, Judge Pierce made a find

ing that minority employment in this industry is less than 2%.

The parties to the settlement agreement stipulated therein that

there is a statistical imbalance within the industry in relation

to those individuals defined as minorities in Title VII.

In this connection, Judge Pierce accepted as credible

the testimony at the trial of the Union's President that the

Union had historically favored employment practices partial to

its members and that the Union v;as not motivated by any intent

to discriminate against minorities. Although Judge Pierce des

cribed this Union position as "admirable under most circumstances",

he ruled that "it is the discriminatory effect of practices and

policies, not the underlying intent, which is relevant in a

Title VII action".

Accordingly, the Defendant-Appellee Union had no

choice except to enter into the settlement agreement which gave

reasonable protection to its members and to all others in the

bargaining unit at the same time that it provided an affirmative

action program which fulfills the objectives of Title VII in

detailing plans whereby a goal of 25% minority employment in

the industry will be reached in five years. To permit Inter-

venor Larkin and a small group of non-minority shapers for whom

he might possibly speak to upset this settlement agreement could

only serve to plunge the employment practices of this industry

-11-

back into the chaos from which it has just emerged.

6 .

In approving the settlement agreement, including its

five-year goal of achieving 25% minority employment in the in

dustry, Judge Pierce asserted that "It is this present impact

of past practices which justifies the affirmative, corrective

relief embodied in the settlement agreement." In so doing he

relied on the United States Stipreme Court's decision in Griggs

v. Duke Power Co., 401 U. S. 424 (1971), as well as on the tri

logy of decisions by this Court in Rios, Wood, Wire, and Bethle

hem Steel, supra. The appellant's efforts to twist the meaning

and effect of these decisions in order to defeat the instant

settlement agreement should not be upheld by this Court.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, this appeal by Intervenor

Larkin should be denied in all respects and the Opinion and Order

of Judge Pierce in the Court below, dated September 19, 1974,

should be affirmed.

Respectfully Submitted,

O'DONNELL & SCHWARTZ

501 Fifth Avenue

New York, N. Y. 10017

Attorneys for Defendant-

Appellee Newspaper & Mail

Deliverers Union of New York

and Vicinity

Michael Klein

Of Counsel