Proposed Order RE: Partial Summary Judgment

Public Court Documents

June 7, 1991

19 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Matthews v. Kizer Hardbacks. Proposed Order RE: Partial Summary Judgment, 1991. b1c857cb-5c40-f011-b4cb-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c09c7903-4ef3-4781-9ce4-d14441487183/proposed-order-re-partial-summary-judgment. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

O

0

0

N

T

O

ae

r

N

e

e

[A

oa

-

-

po

t

fe

ps

t

fe

t

ay

bo

lt

p

t

po

t

~

~

©

WV

0

0

~

3

O

n

W

h

pb

W

W

O

N

H

O

iM 18

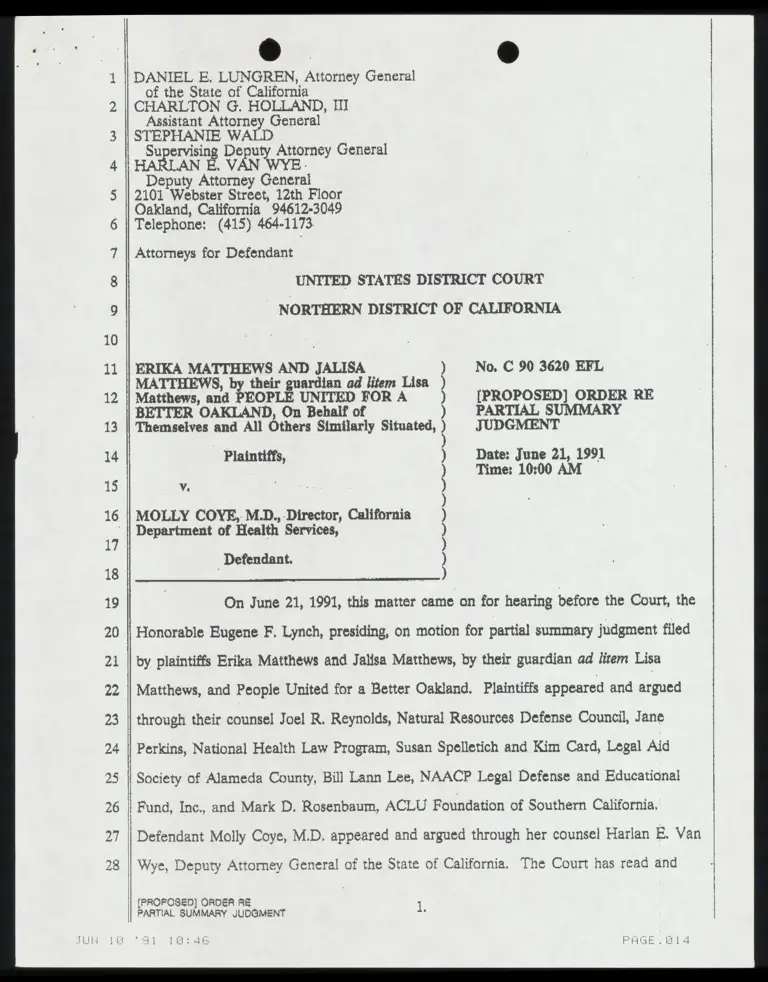

DANIEL E. LUNGREN, Attorney General

of the State of California

CHARLTON G. HOLLAND, III

Assistant Attorney General

STEPHANIE WALD

Supervising Deputy Attorney General

LAN E. VAN WYE

Deputy Attorney General

2101 Webster Street, 12th Floor

Oakland, California 94612-3049

Telephone: (415) 464-1173

Attorneys for Defendant

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA

No. C 90 3620 EFL

[PROPOSED] ORDER RE

PARTIAL SUMMARY

JUDGMENT

Date: June 21, 1991

Time: 10:00 AM

ERIKA MATTHEWS AND JALISA

MATTHEWS, by their guardian ad litem Lisa

Matthews, and PEOPLE UNITED FOR A

BETTER OAKLAND, On Behalf of

Themselves and All Others Similarly Situated,

Plaintiffs,

|

MOLLY COYE, M.D, Director, California

Department of Health Services,

Defendant.

N

r

”

Y

a

”

Sa

ge

Sa

g”

Sp

t?

Na

nt

”

“

o

t

t

ni

t

“

e

t

?

o

p

t

”

“n

at

?

“s

ag

t”

“

v

t

“

a

t

”

“

u

t

”

On June 21, 1991, this matter came on for hearing before the Court, the

Honorable Eugene F. Lynch, presiding, on motion for partial summary judgment filed

by plaintiffs Erika Matthews and Jalisa Matthews, by their guardian ad lirem Lisa

Matthews, and People United for a Better Oakland, Plaintiffs appeared and argued

through their counsel Joel R. Reynolds, Natural Resources Defense Council, Jane

Perkins, National Health Law Program, Susan Spelletich and Kim Card, Legal Aid

Society of Alameda County, Bill Lann Lee, NAACP Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc., and Mark D. Rosenbaum, ACLU Foundation of Southern California.

Defendant Molly Coye, M.D. appeared and argued through her counsel Harlan E. Van

Wye, Deputy Attorney General of the State of California. The Court has read and

(PROPOSED) ORDER RE 1

PARTIAL SUMMARY JUDGMENT .

21 10:40 PAGE.RL14

MI

O0

0

ed

O

n

c

ae

ur

fr

e

considered the moving and responding papers, all supporting papers and appended

documents, the record as a whole and the oral arguments of counsel. The issue having

been duly heard, decision is rendered as follows:

IT I$ HEREBY ORDERED, ADJUDGED AND DECREED:

1 Plaintiffs’ Motion for Partial Summary Judgment is denied on the

grounds that there are no triable issues of fact and that Defendant Molly Coye, M.D,

is entitled to judgment as a maiter of law in that there has been no showing that she

has failed to perform any duty to enforce the Medicaid Act, 42 U, S. C. Sections |

1396a(a)(43), 1396a(a)(4)(B), & (1), as construed in the State Medicaid Manual Section

5123.2(D), by not instructing health care providers who participate in the Medicaid

program to screen all Medicaid-cligible children ages 1-5 for lead poisoning by sing

the erythrocyte protoporphyrin (EP) test as the primary screening test and to perform

venous blood measurements on children with elevated EP levels; |

2 Summary judgment is entered in favor of Defendant Molly Coye,

M.D, igs

3 The Court declares that the Defendant Molly Coye, M.D. isinot in.

violation of 42 U.S.C. Sections 1396a(a)(43), d(2)(4)(B) and (r), as construed by the

State Medicaid Manual, Section 5123.2(D). |

4, Plaintiffs Erika Matthews, et al., are to take nothing; and

!

5 Defendant Molly Coye, M.D., is awarded her costs and fees herein.

DATED:

Prepared by:

DATED: June 7, 1991 "DANIEL E. LUNGREN, Attorney General

of the State of California

bt ithle

Deputy Attorney General

[ei\varwys\maithews.pod] Attorneys for Defendant

PROPOSED] ORDER RE 5

ARTIAL SUMMARY JUDGMENT :

"51. 1047 PAGE. IIS

DANIEL E. LUNGREN, Attorney General

of the State of California

CHARLTON G. HOLLAND, III

Assistant Attorney General

STEPHANIE WALD

Supervising Deputy Attorney General

TAN E VAN WYE |

Deputy Attorney General

2101 Webster Street, 12th Floor

Oakland, California 94612-3049

Telephone: (413) 464-1173

o

s

Attorneys for Defendant

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA yo

og

~J

oy

]

Ln

fe

sd

bo

ek

oO

No. C 90 3620 EFL

DECLARATION OF MARIDEE

ANN GREGORY, M.D.

ERIKA MATTHEWS AND JALISA

MATTHEWS, by their guardian ad litem Lisa

Matthews, and PEOPLE UNITED FOR A

BETTER OAKLAND, On Behalf of

Themselves and All Others Similarly Situated,

Plaintiffs,

E

E

S

T

S

S

FR

EI

Wa

ol

e

0

Ve.

MOLLY COYE, M.D., Director, California

Department of Health Services,

[

S

S

~J

on

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

Defendant. :

—

Co

| o

o

T

E

ic

V

E

R

E

I, MARIDEE ANN GREGORY, declare:

1 1 am a Doctor of Medicine and a Board Certified Pediatrician. I have

N

N

N

e

spent my entire professional career since 1965 in the area of maternal and child health.

23 || I was first employed by the State Department of Health Services in 1981 as Chief of

24 || Maternal and Child Health. Since 1987 I have served as chief of the California

25 || Childrens Services Branch within the Department. I also serve as medical consultant to

26 || the Child Health and Disability Prevention Branch of the Department and have been

27 || the medical consultant in the drafting of program letters regarding lead screening and DECLARATION OF MARIDEE ANN GREGORY, M.D.

Jil 18 Sl adn PAGE .B1E

w

w

0

0

~

~

G

v

W

n

p

x

WW

N

N

Fo

SE

oF

E

E

2°

EE

r

t

c

d

a

d

m

R

=

SO

0

S

y

S

O

S

y

|

N

N

=

O

O

Ww

W

0

0

9

0

R

h

n

h

A

W

N

=

D

D

23

testing matters within the last four or five years.

2 The matters stated below are personally known to me and if called as a

witness I could and would testify competently concerning the same,

3 The Department of Health Services does not dispute the seriousness of

the problem of lead poisoning in children. In fact, as recently as March 12, 1991, the

Department’s former Director, Dr. Kenneth Kizer stated that: "Lead poisoning is the

most significant environmental health problem facing California children today, and

insufficient consideration is being given to this potential problem during routine child

health evaluations."y What the Department does dispute is whether either the law or

good medical practice requires the actual testing of children’s blood for the presence of

lead in all cases, and particularly very young children in the Early and Periodic

Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment ("EPSDT") Program of the Federal Medicaid

Program (known as the Medi-Cal program in California, and administered by the

Department of Health Services). |

4, The Department believes that neither applicable laws nor good medical

practice requires that all EPSDT children receive blood lead tests as a part of the

mandatory screening process. Rather, it is the Department's position that young (i.e,

under 6 years old) EPDST children should first be screened by their treating physicians

for both the presence of objective medical indications and/or environmental factors

which might indicate the possibility of lead toxicity. If either or both are present then

a blood test would be indicated. |

5 A blood test is an intrusive procedure which causes some degree of

discomfort, and in the vast majority of cases is simply unnecessary to determine

whether a child is at risk of lead poisoning. Further, there is a significant cost factor

involved in completing a blood test which must be considered in an age of limited

JUN 13

1. CDHP Provider Information Notice #91.6, included as Exhibit C in the

Exhibits In Support Of Plaintiffs’ Motion For Partial Summary Judgment.

2

DECLARATION OF MARIDEE ANN GREGORY, M.D.

SY Dean FREE B17

v

v

o

o

3

9

O

n

U

n

p

b

W

W

O

N

O

8

S

E

AS

E

E

r

l

a

r

d

ee

ee

oe

=

SE

=

SR

=

O

O

W

Y

0

0

0

«

3

‘

o

n

W

h

5

3

J

=

TD

resources, although the Department has been absolutely LA in its communications

with physician/providers that the cost of a blood test for lead is a covered cost in the

Child Health and Disability Prevention Program (see the penultimate paragraph of

CHDP Provider Information Notice #91-6). The message the Department sends to

physicians is that blood lead tests should be given to young EPSDT children whenever

and wherever medically indicated and that cost is not a factor -- good medical

judgment is.

6. While it is recognized that certain pediatricians advocate universal blood

lead testing for young children, that position is not universally shared. On March 3,

1987, the American Academy of Pediatrics published its Statement On Childhood Lead

Poisoning in its journal Pediatrics While recognizing as an ideal the concept of

anlversal blood lead testing, the Statement recognized that ". . . the incidence of lead

may be so low in certain areas that pediatricians may prudently consider their patients

to be at little risk of lead toxicity . . "& and set out priority guidelines to assist

pediatricians in deciding whether the need for a blood lead test was indicated.

i On June 4, 1991, I spoke by telephone with Raymond J. Koteras, M.H.A,,

Director of the Division of Technical Committees, of the Department of Maternal,

Child and Adolescent Health of the American Academy of Pediatrics. Mr. Koteras

confirmed to me that, while the matter of child blood lead testing is currently under

review by several Academy committees, the aforementioned Statement is and remains

the position of the Academy.

8. The Department believes that its position is consistent with the

requirements of the Health Care Financing Administration's ("HCFA") State Medicaid

Manual (included as Plaintiffs’ Exhibit N) wherein it is stated that a blood lead level

2. A copy of this Statement is attached hereto as Exhibit A.

3. Op. cit, at p. 463.

DECLARATION OF MARIDEE ANN GREGORY, M.D.

‘91 10:49 PAGE OLE

po

t

O

o

0

0

~

1

O

v

b

h

B

B

W

O

=

O

O

N

N

N

N

R

N

R

N

=

p

d

F

S

p

t

e

d

p

e

d

e

t

ea

d

~~

h

n

a

n

B

W

N

O

E

DO

O

W

O

0

0

N

h

l

R

W

N

R

C

assessment is mandatory where age and risk factors so inaicate. (Ex. N, at p. 5-14)

The Manual goes on to specifically require that all Medicaid eligible children ages 1-3

be screened for lead poisoning. However, the Manual section wherein the requirement

to screen is contained also contains several significant caveats concerning testing:

"Physicians providing screening/assessment services under the EPSDT program use their

medical judgment in determining the applicability of the laboratory tests or analysis to

be performed. ... As appropriate, conduct the following laboratory tests: . .. 1 In

general, use the EP test as the primary screening test." (Ex. N, at p. 5-14 through J-

15) Clearly, the ultimate decision as to whether a blood lead test should be given has

been left to the determination of the physician.

0. It is the present belief of the Department that universal blood lead

testing of young EPSDT children is not medically indicated, legally required nor fiscally

prudent.

I declare under penalty of perjury that the foregoing is true and correct.

Executed at Sacramento, California this 6th day of June, 1991.

Hunecdter Kom Biug ong Wp

DECLARATION OF MARIDEE ANN GREGORY, M.D.

EXHIBIT A

FAGE . B26 J 18 a0 10:80

Ef

a

. aT

pe

FE

8

*t

Kd

c

a

tn

tn

e

vr

ra

re

:

im

g

m

A

T

T

MEY

N

V

A

Go

ds

n

y

s

f

t

des

Le

m

T

a

H

e

Aq

Cle

h

o

li

en

El

ar

Er

a

L

R

S

T

C

R

R

N

pi

E

R

T

E

N

a

E

bs

.

e

a

pe

a

Lis.

+

To

e

h

d

d

p

T

Poa

gl

i

-

A

r

C

i

t

i

i

p

e

i

l

s

R

E

E

N

E

i

Committee on Environmental Hazards

Committee on Accident and Poison Prevention

Statement on Childhood Lead Poisoning

!

Lead remains a significant hazard to the health

of American children. Virtually all children in

the United States are exposed to lead that has been

dispersed in air, dust, and soil by the combustion

of leaded gasoline, Several hundred thousand chil-

dren, most of them living in older houses, are at

risk of ingesting lead-based paint as well as lead-

bearing soil and house dust contaminated by the

deterioration of lead-based paint. Although the in-

cidence of symptomatic lead poisoning and of lead-

related mortality has declined dramatically,’ date

from targeted screening programs’ and from a na-

tional survey” show that there are many asympto-

matic children with increased absorption of lead in

—

—

—

—

—

_

_

—

—

_

—

—

—

i

>

all regions of the United States. It is particularly

prevalent in areas of urban poverty.

Childhood lead poisoning can readily be detected

by_ simple and inexpensive screening’ techniques;

however, screening is sporadic and in some areas

not available. :

Despite wide recognition of the importance of

preventing children’s exposure to lead, state and

federal funding for the screening of children and

for the removal of environmental lead hazards has

diminished in recent years. Thus, pediatricians at-

tempting to address the problem of childhood lead

exposure face serious economic and administrative

obstacles to effective intervention,

This statement reviews current approaches to the

diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of lead poi-

soning, and it recommends steps to reduce the

pervasive impact of lead on children’s health. Some

of these recommendations are addressed to practi-

tioners and others to agencies of state and federal

government. It is important to recognize that vir-

tually all of these preventive steps are after the

fact, Ideally, in keeping with the precepts of pri-

mary prevention, lead should have been prohibited

from ever having become dispersed in the modern

environment.

PEDIATRICS (ISSN 0031 4005). Copyright © 1887 by the

American Academy of Padiatrics. ;

BACKGROUND AND DEFINITIONS

Lead has no biologic value. Thus, the ideal whole

blood lead level is 0 ug/dl.. According to the Second

National Health and Nutrition Examination Sur-

vey (NHANES II), conducted from 1876 to 1980,

the mean blood lead level in American preschool

children was approximately 16 ug/dL. Substantially

Jower lead levels are seen in persons remote from

modern industrialized civilization® and in the re-

mains of prehistoric men.

Until recently, whole blood lead levels as high as

30 ug/dL wera considered acceptable. However, dia-

turbances in biochemical function are demonstrable

at concentrations well below that figure, For ex-

ample, inhibition of 3-aminolevulinic acid dehy

drase, an enzyme important to the synthesis of

heme, occurs at whole blood lead levels below 10

pg/dL.¥® Also, the enzyme ferrochelatase, which

converts protoporphyriti to heme, is inhibited in

children at a blood lead concentration of approxi:

mately 156 pg/dL; thus, elevations in erythrocyte

protoporphyrin above normal background become

evident at blood lead levels above 15 pg/dL.? In

addition, depression of circulating. levels of 1,25:

dihydroxyvitamin D (the active form of vitamin D)

is seen at blood lead levels well below 25 ug/dL, 1!

Neuropsychologic dysfunction, characterized by

reduction in intelligence and alteration in behavior,

Ww

has been shown conclusively to occur in asympto:

matic children with elevated blood lead levels. et

The results of clitiical And epidefiiclogic “studies

matic childr

conducted in the United States,” Germany,” and

England" indicate clearly that blood lead levels

below 50 ug/dl. cause neuropsychologic deficits in |

asymptomatic children. Recent clinical and exper:

imental studies suggest that neuropsychologic dam:

age may be produced in children with blood lead

levels below 35 pg/dL.!®

Short stature, decreased weight, and diminished

chest circumferenre have recently been found in

analyses of data'ft,m the NHANES II survey to be

significantly associated with blood lead levels in

American children youngér. than 7 years of age,

PEDIATRICS Vol. 78 No. 3 March 1987 ~~ 457

PRISE. B21

after controlling for age, “= and nutritional earth’s crust, lea y be found in drinking water,

.gtatus. Although the effectN@le small, the results soil, and vegeta its Jow melting point, malles. ARNE

are statistically robust, bility, and high density, as well as its ability to form

In light of these data, an expert Advisory Com- alloys, have made lead useful for myriad purposes,

mittee to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) --Many of these uses (eg, radiation shields, storage CHEE]

has determined that a blood lead level of 25 ug/dl. batteries) are not intrinsically dangerous, However,

or above indicates excessive lead absorption in chil- when lead is used for purposes other than intended IER

dren and constitutes grounds for intervention.) . (eg, burning of storage battery casings), when it js

Increased lead sbsorption was previously defined incorrectly applied or removed (eg, improper use of

by a blood lead level of 30 g/dL. Furthermore, the lead ceramic glazes, burning and sanding of old

CDC committee has now defined childhood lead leaded paint), when it is disseminated rather than

poisoning 8s a blood lead level of 25 ug/dL in reused (combustion of lead additives in automotive

association with an erythrocyte protoporphyrin fuels), or when it is improperly discarded, lead

level of 85 ug/dL or more.’ The Academy concurs enters the human environment in potentially haz-

in these definitions. Also, the Academy anticipates ardous form.

that as evidence of the low-dose toxicity of lead For purposes of estimating risk to children, bad

continues to develop, these definitions will be low. sources may be categorized as low, intermediate,

ered still further, and high dose (Table 1).

: : Low~Dose Sources. These sources of lead include ;

PREVALENCE OF LEAD POISONING air, food, and drinking watar, Together, these

Data from NHANES II? indicate that between EOUTCES, which have accounted for an average esti |

1976 and 1980 the national prevalence of blood lead ~~ ated blood lead concentration of approximately 3

levels of 30 ug/dL or hicher was 4% amonz Amer. 10 #8/dL in the recent past, probably now account 3

loart 0080 141 BL os High 5 years of age. ac for a blood level concentration of about 6 ug/dL. 2

this rate to US census data, it may be estimated Mean ambient air lead concentrations currently 3

that, between 1876 and 1980, 780,000 American Everage less than 1 ug/m’ of sir, although in areas

preschool children had excess levels of lead in their ~~ P&T lead smelters, concentrations may be Retin: 2

blood. In the NHANES II data, there was wide tially higher. et |

disparity in the prevalence of elevated blood lead Average dietary intake of lead increases from 20 4 ii Ht

levels between black children (12%) and white chil. #&/d during early infancy to 60 to 80 4g/d by 5 to" = x]

dren (2.0%) irrespective of social class or place of © Years of age. Except in isolated areas, it would: JE

residence. A similar disparity was noted in mean 2PPear that the majority of public drinking water 3 5

blood lead levels, which were 21 pg/dL in black supplies in the United States have a lead concen-. a |

preschool-aged children and 15 g/dL in white chil- tation of less than 20 g/dL. However, these data S4t=

dren of the same age. Prevalence rates for elevated T2Y be misleading if, as is generally the case, the “ZoE

blood lead levels were highest among families in Water samples have been obtained from the distri-

densely populated urban areas and in those with Pution plant prior to the distribution of water

incomes of less than $15,000 per year, However, it through a plumbing system that contains lead,

should be noted that cases of lead poisonings were pipes. The lead solvency of drinking water can be;

found also in families of higher income and in rura] ~ éduced by reducing acidity of water supplies an

settings. by abandoning the use of lead-based solder at pip

Between 1976 and 1980, the average blood lead J0ints in new and replacement plumbing. Compu

level in Americans of all ages decreased from 15.8 nities with excessive lead in water have successfully

t0 10.0 ug/dL according to the NHANES IL# This used each of these remedial approaches.

decrease coincided with a reduction in the use of TABLE 1. Common Sources of Lead

lead additives in gasoline. Additional factors in this Low Goce

_ reduction may have included a simultaneous reduc- Food

tion in the Jead content of foodstuffs, the impact of Ambient alr

targeted screening programs in high-risk areas, and Drinking watar

an increase in public awareness of the hazards of Intermediate dose

lead. Dust (housahold)

Interior paint removal

Soil contaminated by automobile accident

Industrial sources

: : Improper ve Envirenmenis Sources ali moval of exterior paint

Intsrior and sxterior pamt

SOURCES OF LEAD

Lead is ubiquitous. A natural constituent of the

458 LEAD POISONING

J

!

1

+

[4

H

I

}

Pont |

UF

a

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

r

r

a

0

e

S

B

a

r

SY

o

n

r

e

rag

: | 5 Intermediate-Dose Source

¥= clude dust and soil in children's play areas. Dust

¥. and soil are contaminated principally by automo-

hese sources in-

tive exhaust and by the weathering and deteriora-

i tion of old lead paint (both interior and exterior).

Although background soil lead contaminants in

3 rural areas are generally less than 200 ppm, concen-

BE {rations of lead in urban soil can exceed 8,000 ppm.

Ei In industrial areas where lead smelters have been

BE Gituated (eg, El Paso, TX; Kellogg, ID), the lead

: *" sontent of dust can, however, exceed 100,000 ppm,'®

5% thus producing significant elevations in children’s

L>. blood lead levels. Each increase of 100 ppm in the

: 4 ." lead content of surface soil above a level of 500 ppm

8%. is associated with a mean increase in children's

r

N

-

i

"

.

SAN

I

L

s

A

r

T

CS

S

E

A

N

ot

Ri

n:

snr

ri

de

r

i

d

A

T

T

o

m

e

p

t

a

u

t

4

I

T

E

R

L

O

R

E

L

S

E

pr

ic

e.

io

}

a

l

e

R

d

R

E

M

HE

RR

ETS

+

4

a

a

t

EE

Sk

ca

li

d

a

t

a

cs

La

o

*5

oy

—

—

—

3 2 whole blood lead levels of 1 to 2 pg/dL. When dust

and soil are the only sources of exposure to lead,

5 symptoms are rarely encountered, although lead

toxicity may occur. Soil lead may, however, be

‘extremely difficult to abate, and chronic low-grade

ingestion may continue undetected even after a

child has come to medical attention. The proper

sita for disposal of 1sad waste, such as Jsad-contam-

inated soil, is a hazardous waste facility that has

been approved by the US Environmental Protec-

tion Agency. :

High-Dose Sources. These sources are those in

which the concentrations of lead are sufficient to

produce acute and potentially fatal illness, Lead-

based paint on both the interior and exterior sur-

faces of housing remains the most common high.

dose source of lead for preschool-aged children. It

continues to be the experience of most pediatricians

that virtually all cases of symptomatic lead poison-

ing and blood lead levels greater than 70 ug/dL

result from the ingestion of lead paint chips.

Lead-based paint, is still widespread. A 1878 US

census survey found that 8 million of the 27 million

occupied dwellings in the United States, which had

been built prior to 1940 when use of lead-based

paint was common,?® were deteriorated or dilapi-

dated. An additional 22 million dwellings were built

between 1940 and 1960, and 76% of these units are

estimated to contain lead-based paint. Nationally,

according to the 1978 census survey of housing, 8%

of rental units have peeling paint.

Although the use and manufacture of interior

lead-based paint declined dramatically during the

1950s, exterior lead-based paint continued to be

available until the mid-1970s and is still available

for maritime use, farm and outdoor equipment, road

stripes, and other special purposes. Thus, potential

for domestic misuse of lead-based paint continues

to exist. Manufacturers could voluntarily decrease

the lead content of interior paint until 1977, when

the US Consumer Product Safety Commission en-

acted regulations ing the sale in interstate

commerce of paints yor exposed interior and exte-

rior residential surfaces containing ‘more than

0.08% lead by weight in final, dry solid form.

A previously unforeseen, but increasingly recog-

nized, danger is that of improper removal of load.

based paint from older houses during renovation

or, ironically, during cleaning to protect children.

"Torches, heat guns, and sanding machines are par-

ticularly dangerous because they can create a lead

fume. Sanding not only distributes lead as & fine

dust throughout the house but also creates small

particles that are more readily absorbed than paint

chips. The greatest hazard in paint removal appeats

to be to the person doing the “deleading” and to

the youngest children in the dwelling. There may

be significant morbidity, Persons who perform this

work should comply with the standards for occu-

pational exposure to lead which have been devel.

oped by the US Occupational Safety and Health

Administration. Pregnant women, infants, and

children should be removed from the house until

deleading is completed and cleanup accomplished.

Proper cleaning of the dust and chips produced in

deleading must include complete removal of all

chipping and peeling paint and vacuuming and

thorough wet mopping, preferably with high-phos-

phate detergents. This waste must be discarded in

a secure site, |

Another previously unrecognized hazard lies in

sandblasting. This technique is commonly used to

_ remove lead from exterior surfaces. There are no

standardized safeguards. Recent case reports of lead

poisoning among sandblasters underscore the haz-

ard. Sandblasting creates large amounts of lead-

laden dust and debris which, if improperly disposed

or not properly removed, redouble the hazard,

Uncommon Sources (Table 2)

Additional lead sources include hobbies such ‘as

artwork with stained glass and ceramics, particu-

larly when conducted in the home. Folk medicines

TABLE 2. Uncommon Sources of Lead

Metallic objects (shot, fishing weight)

Lead glazed ceramics

Qld toys and furniture

Storage battery casings

(Gasoline sniffing

Lead plumbing

Exposed lead solder in cans

Imported canned foods and toys

Folk medicines (eg, azarcon, Grata) -

Leaded glass artwork

Cosmatics

Antique pewter

Farm equipment hi

AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS 459

PAGE . 827

Jead and mercuric or arseni

‘480

iiments may contain

alts. Recent reports

have noted lead poisoning from use of azarcon (lead

tetroxide)* and Greta (lead monoxide) among Mex-

ican-Americans and from use of Pay-loo-ah, a

used to treat gastrointestin

Chinese folk remedy,” among Hmong refugee chil- _

dren. Cosmetics (ceruse, surma, or kohl), particu-

larly those from Asia, may contain white lead or

lead sulfide®*” and have caused severe lead poison-

ing. Another source of lead is improperly soldered

cans, particularly those containing acidie food-

stuffs. Food should not be heated in such cans, as

heating increases the dissolution of lead. Pediatri-

cians should realize as a practical matter that the

lead content of imported earthenware toys, medi-

cines, or canned foods cannot readily be regulated,

In addition, antique toys, cribs, and utensils may

have a significant lead’ content.

Lead-glazed pottery is ‘a potential | source of lead

int food and drink, If not fired at high temperatures, ii

lead may be released from the glaze in large

amounts when such pottery is used for cooking or

for storage of acidic foodstuffs. Also, if pottery

vesgels are washed frequently, even a properly fired

glaze can deteriorate, releasing unsafe levels of pre-

viously adherent lead.” Sporadic cases of plumbizm

have been traced to lead-glazed pottery.®

Among the oldest sources of lead in America is

antique pewter. Food should not be cooked or stored

in antique pewter vessels or dishes. Although un-

common, many of the above sources have been

associated with severe, symptomatic, and even fatal

lead poisoning.

Finally, a number of cases of lead poisoning have

been reported among the children of workers in

smelters, foundries, battery factories, and other

lead-related industries. ® These workers can bring

home highly concentrated lead dust on their ekin,

shoes, clothing, and automobiles. This source of

exposure can be avoided by providing showers at

work, by providing workers with a change of cloth-

ing, and by having clothing laundered at the work-

place.

In summary, it can be inferred from the

NHANES I] data that most children in the United

States with increased lead absorption have been

#xposad to low-dose or to intermediate-dose lead

sources. Four percent of children have blood lead

levels in excess of 30 ug/dL, but only 0.1% have

levels exceeding 50 pg/dL.?

ROUTES OF ABSORPTION

Ingestion is the principal route of lead absorption

in children. Because of the high density of leadt®

ingestion of surprisingly small quantities may pro-

duce toxic effects. A lead paint chip weighing only

LEAD POISONING

. containing 5% le

lead poisoning. However, most ingested chips pre

"of the lead containad in them unavailable for ab-

tivenesé of normal hand-to-mouth activity ss =a

means for the transfer of lead-laden dust from the

though still an important risk factor, need not/be

sorption for children, Lead absorbed by way of the

‘Tungs contributes in additive fashion to the total

by ciliary action and then are either expectorated 3

Rk 1 em’ in purface area) and

weight will deliver a potential . I'§

dose of 50 mg (50,000 ug); by comparison, the safe ~i8

upper limit for daily intake of lead by children js 5 1%

pg/kg of body weight.) Because ingestion of such OJ

chips is not uncommon, it might be expected

large numbers of children would have symptomatic

1 g (approxima

swallowed whole or in barge pieces, rendering much

sorption.

Several recent studies have reported the effec- |

iR

Ba

d.

..

oi

a

i

n

iy

a

)

he

ar

th

i

C

o

p

rT

e

a

Pt

Sa

ga

=

-

"

x

y,

F

k

.

Fi

T

e

AOR

F

e

a

P

T

S

R

I

R

F

Rak

oo

ii

n

t

e

,

H

T

re

environment into children, ®* True pica (the in-

discriminate ingestion of nonfood substances), al

du

“a

d

ii

:

[TI

NY

present.

Inhalation is the second major route of lead ab.

body lead burden. The efficiency of respiratory 8

absorption depends on the diameter of airborne WE

lead particles, For most common lead aerosols of

mixed particle size, it has been estimated thet be. - 38

tween 30% and 50% of total inhaled lead is con- “H¥

tained in particles of sufficiently small diameter HE

(less than 5 um) to be retained in the Jungs and THR

absorbed. Larger particles deposit in the nose, ih

throat, and upper airways where they are cleajed SH

or swallowed. g

(x3

PREDISPOSING FACTORS J

Factors known to increase stsmeptiitity to lead

toxicity include nutritional deficiencies and age-

related oral behavior (with or without pica) (Table

3).

Anima] and human studies®’ have shown that ; 3

deficiencies of iron, calcium, and zine all resultiin “EEE.

increased gastrointestinal absorption of lead. of i: :

particular concern is the effect of lack of iron,” :X because the prevalence of iron deficiency in infancy &

is at least 156% and may be higher. * Iron deficiency, if

even in the absence of anemia, appears to be the*%

single most important predisposing factor for in a

creased absorption of lead, Conspicuous example

of nutritional iron deficiency include-breest.fed in-°

fants and “milk babies” who may receive little food 3

TABLE 3. Predisposing Factors for Lead Poisoning

Nutritional deficiency of iron, calcium, TrR2ANE |

Sickle cell diseases

Young age

Hand-to-mouth activity, including pica

Metabolic diseases

-,

FAGE . B2

-

r

d

i

(

L

p

SL

REN

-

oF

g

a

g

=

*

>

1

Pa

ce

v

3

L

a

b

da

4

n

-

L

E

B

r

i

J

fr

ie

&

ng

t

e

r

r

e

dt

:

A

ey

Sols

pied

dhe

,

f

o

r

t

=

: =

:

E

e

“=

.

i

b

.

iL

©

1

e

t

g

e

a

t

e

eb

=

Bother chan milk until 12 ("18 months of age. In

K...the presence of ifon deficiency insufficient to pro-

duce anemia, gastrointestinal absorption of lead is

2, increased aeveralfold.

SCREENING

Screening for lead poisoning is sporadic, Methods

used have included determination of blood lead

level, erythrocyte protoporphyrin level, or both,

A risk settings or with significant predisposing

BY - tors.'” To guide the interpretation of screen:

=. sults, the CDC has developed a series of guidelines

= (Tables 4 and §).

The erythrocyte protoporphyrin determination

provides a sensitive and inexpensive screen for both

increased lead absorption and iron deficiency, two

of the most common preventable health problems

in childhood; elevation in the erythrocyte proto-

porphyrin level can reflect iron deficiency before

anemia becomes clinically evident. There is increas-

ing interest, therefore, in adopting the erythrocyte

protoporphyrin determination as a screening tool

for both problems, particularly because it is more

sensitive to iron deficiency than the hematocrit. ™

Both capillary tubes and filter paper have been

B® ced for obtaining screening samples. Capillary

tubes are cumbersome but have the advantage of

providing sufficient blood for concomitant lead de-

TABLE 4. Zinc Protoporphytin by Hematofluorometer:

Risk Classification of Asymptomatic Children for Prior-

ity Medical Evaluation”

Erythrocyte

Protoporphyrin

: (ug/dL)

“35 35-74 75-174 >176

1 1

Ia 1

III IT1

II Iv

IV IV

* Diagnostic evaluation is more urgent than the classifi-

cation indicates for (1) children with any symptoms

compatible with lead toxicity, (2) children younger than

"36 months of age, (3) children whose blood lead and

erythrocyteprotoporphyrin levels place them in the upper

part of a particular-class, (4) children whose siblings are

in a higher class, These guidelines refer to the interpre-

tation of screening results, but the fina] diagnosis and

+ disposition reshon.a more complete medical and labora-

tory exanitpnioneiithe child,’

t Blood lead test-needed to estimate risk. bi

+ Erythropoietic. protoporphyria. Iron deficiency may

cause elavated erythrocyta protoporphyrifiievels up to

300 ug/dL, but this is rare. :

§ In practicgsthis combination of results is not generally

observed: ifi¥ is observed, immediately retest with whols

TABLE 6. erie Protoporphyrin (EP) by Extrac-

tion: Risk Classification of Asymptomatic Children for

Priority Medical Evaluation®

Blood Lead

(ug/dL)

Not done

EP (ug/dL)

«35 85-108 110-248

1 t t

1 Ia Ia

Ib II II

8 II go

i 4 NN

* Diagnostic evaluation is more urgent than the classifi-

cation indicates for (1) children with any symptoms

compatible with lead toxicity, (2) children younger than

38 months of age, (3) children whoae blood lead and EP

lavels place them in the upper part of a particular class,

(4) children whose siblings are in a higher class, These

guidelines refer to the interpretation of screening results,

but the final disgnosis and disposition rest on a more

complete medical and laboratory examination of the

child. Screening tests are not diagnostic, Therefore, every

child with a positive screening test result should be

referred to a physician for evaluation, with the degree of

urgency indicated by the risk classification. At the first

diagnostic evaluation, if the screening tast was done on

capillary blood, & venous blood lead level should be de-

tarmined in a laboratory that participates in the Centers

for Disease Control's blood lead proficiency-testing pro-

gram. Even when tests are done by experienced person-

nel, blood lead lavals may vary 10% to 15%, depending

on the level being testad. Tests for the same child may

vary as much as £5 ug/dL in a 24-hour period. Thus,

direction should not necessarily be Interpreted as indie-

ative of actual changes in the child's lead absorption or

excretion.

t Blood lead test needed to estimate risk.

} Ervthropoistic protoporphyria. Iron deficiency may

cause alevated EP levels up to 300 pg/dL, but this is rare,

§ In practice, this combination of results is not generally

Shietvad if it is observed, immediately retest with whole

blo ;

termination if the erythrocyte protoporphyrin level

is elevated. Filter paper sampling provides ease of

collection and transport, but the accuracy of anal.

yases based on filter paper samples is not yet estab-

lished. Determination of the blood lead level by

fingerstick sampling is subject to contamination by

lead on the skin, whether collection is by capillary

tube or filter paper. Such contamination does not

affect the determination of the erythrocyte proto-

porphyrin level,

Two analytical techniques are available for de-

termination of erythrocyte protoporphyrin: (1) ex-

traction of protoporphyrin from erythrocytes and

subsequent measurement in a fluorimeter and (2)

dirsct fluorimetry of a thin layer of RBCs (hema-

tofluorometer). Because values derived from these

two methods may differ (Tables 4 and 6), a pedia-

trician should be aware of which is in use. When in

doubt, the extraction method is preferred, because:

of its greater reprodudibility, particularly at lower

concentrations of erythrocyte protoporphyrin.

AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS 461°

PAGE. OFS

i

}

!

It is most important that screening tests

are not diagnostic. EveM®child with a positive

screening test result should be referred to a pedia-

trician for further evaluation, with the urgency of

referral indicated by the risk classification (Tables

4 and 5). At the first diagnostic evaluation, if the

sereaning test was performed on capi od, &

venous blood lead level should be i p

“laboratory that participates in en aggredited blood

lead proficiency-testing program. To reduce the

RRSTooT ot TElseoetye roFalts, lead-free ay-

ringes, needles, and tubes must be used in obtaining

venous blood samples for lead analysis,

The developmentally disabled who reside in

“halfway houses” or cornmunity residences or who

attend school in older buildings deserve special

attention in lead-screening programs, Because this

population may be older than preschool age, pro-

tective statutes may not recognize their high-risk

status, particularly with respect to piea behaviors,

Physicians caring for developmentally disabled pa-

tients should be aware that their risk of lead inges-

tion may continue long beyond the age of & years.

INTERVENTION

Once a diagnosis of increased lead absorption has

been confirmed by venous blood lead determina-

tion, the sine qua non of intervention is the prompt

and complete termination of any further exposure

to lead.*® This intervention requires accurate iden-

tification of the source of lead and either its removal

or removal of the child from the unsafe environ-

ment, Some states (eg, Massachusetts) have passed

stringent legislation requiring prompt removal of

lead hazards in cases of lead poisoning, and there

are strong penalties for failure to comply. At all

costs, a child should not be permitted to enter or to

be present in a leaded environment during deleading

until the deleading, subsequent cleanup, and rein.

spection have been satisfactorily completed, Al-

though some regulations call only for removal of

leaded paint from “chewable” surfaces (eg, window

sills and door frames) or up to a height of 1.2 m (4

ft), all chipping and peeling paint should be re-

moved from all surfaces, particularly from ceilings,

After deleading, the house must be thoroughly

cleaned and reinspected to assure compliance with

safety regulations. Indeed, repeated thorough clean-

ing is advisable, especially in the case of deterio-

rated or dilapidated housing, High-phosphate de-

tergents are particularly useful in removing lead

dust. Children should not return home until ¢clean-

ing is completed.

Medical intervention should begin with thro-

rough clinical evaluation iIn®4ding diagnostic stud-

les of lead toxicity and, when indicated, & lead

mobilization test.** Diagnostic studies should in-

482 LEAD POISONING

clude a blood gl count with RBC indices, a retic-

ulocyte count, Qt, if indicated and available, tests

of serum iron and iron-binding capacity, and a

serum ferritin assay. Routine urinalysis might be

considered. Because chelating agents are poten-

tially nephrotoxic, BUN and/or serum creatinine

values should be determined before chelation to

rule out occult renal disease either secondary to

plumbism or preexisting,*’ Roentgenographic stud-

ies to be considered include & film of the abdomen

to detect radiopaque paint chips or other leaded

materials in the gastrointestinal tract and a film of

the metaphyseal plate of a growing “long” (bone,

usually the proximal fibula, to detect interférence

with calcium deposition, the so-called “lead line,”

Because this phenomenon is usually seen only after

several weeks of increased lead absorption in chil-

dren whose blood lead levels may exceed 50 ug/dL,

its presence or absence may help to determine the

duration of increased lead exposure.

Once a diagnosis of plumbism has been made, a

child's condition and the effect of intervention

should be monitored by serial venous determina-

tions of the blood lead and, if available, erythrocyte

protoporphyrin levels. If iron deficiency is présent,

iron studies should also be repeatad periodically to

monitor compliance with iron replacement therapy.

The lead mobilization test may be used to dssess

the “mobilizable” pool of lead in a child for whom

chelation therapy is contemplated. Lead moHiliza-

tion is determined by measuring lead diuresis in &

timed urine collection following a single dose of

chelating agent.®# This test is most helpful in

determining which children with blood lead concen-

trations in the range of 25 to 55 ug/dL will require

a full course of chelation therapy and also in deter-

mining the advisability of further chelation in a

child already receiving therapy. It should be noted

that the erythrocyte protoporphyrin level is hot a

useful predictor of the amount of chelatable lead

and may, in fact, be misleading in this regard.

-

e

r

p

b

i

h

aT

E

E

.

ai

s

r

r

Ay

SW

NH

BE

RL

IN

E

1

O

sc

E

R

E

:

-

-

'

-

=

EE

F

E

e

L

r

E

L

s

e

t

s

Therapeutic modalities include removing the -.;

child from lead exposure, improving nutrition,

administration of iron supplements, and chelation 3:

therapy.***~4" In children with mild increased lead

absorption, the efficacy of chelation therapy to ]

modify neurobehayioral outcomes-of-lead. toxicity

13 unproven: but, in children who have blood lead

levels between 25 and 55 pg/dL and a positive lead

mobilization test, it is highly desirable to rapidly

decrease the readily mobile, potentially most toxic

f

bs

ay

fraction of body lead stores by three to five days of >

CaNay-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (caltium 3)

disodium EDTA) therapy, *

Long-term follow-up is indicated in all cases of 2;

lead exposure. Children near or at school age who 70

have a history of plumbism should have a neuro- 2

a

n

e

B

t

t

e

h

e

r

s

i

x

D

E

a

a

>

a

*

-

—

—

—

k |

-

T

H

u

~

"

.

i

=

p

.

psychologic evaluation to » potential learn-

ing handicaps, and school authorities should be

8 encouraged to offer appropriate guidance.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Our recommendations rest on three premises: (1)

that exposure to lead is widespread; (2) that lead

causes neuropsychologic and other serious impair-

ments in children at relatively low levels of expo-

© sure; and (3) that the neuropsychologic effects of

: lead, even in asymptomatic children, are largely

irreversible. Guided by these premises, the goal of

>. our recommendations is to prevent lead absorption.

O

Pediatricians must play a central role in this

prevention. Although our recommendations are di-

vided into two categories—those directed princi-

pally to practitioners and those directed to govern-

ment agencies——the distinction is somewhat artifi-

cial. Throughout the past five decades, pediatri-

cians, acting individually, as well as collectively

through the Academy, have been prime movers in

stimulating the agencies of government to protect

the children of the United States against exposure

to lead. It is important that this tradition of public

involvement continue and that pediatricians con-

tinue to act publicly as advocates for the health of

children.

Recommendations for Practitioners

1. The Academy recommends that the erythro-

cyte protoporphyrin test be used for screening chil-

dren for lead toxicity, when that test is available.

Additionally, the erythrocyte protoporphyrin test

is a sensitive indicator of subclinical iron deficiency

and may add complementary information to the

determination of hematocrit values. It will not,

however, identify children with anemia due to acute

blood loss or hemoglobin C, 88, 8C, or E disease.

The Academy encourages clinical and hospital lab-

oratories to make the erythrocyte protoporphyrin

test widely and economically available,

2, Upon consideration of recent CDC recommen-

dations, the Academy recommends tnat, 1aeally, all

‘preschool children should be screened tor ead ab-

sarption.by_mesns..of the srihrooyie DIAG

Dv Lh uel in-

cidence of Si exXpOosy ow ip certain

areas that pediatricians may. Sr consider

their patients to be at little risk of Tead toxicity;

therefore, the following priority y guidelines ranked’

from -highegt, to lowest are offered to assist ¢ pedia-

tricians in deciding which children to sci to screen. (a)

children, 12 12 1 10.36 months of ' age, | who Ii live ir in or are

frequent visitors in ol older, _dil lapidated housing

(highest); (b) children, 8 power of to 6 years of age,

who are siblings, housemates, ‘visitors, ang, play-

d toxicity; (c)

lire, none gs ap I ie

lead smelters and processing pl »

«amis or.other househo es

lead-rela ation or ‘hobby. Frequency

screening should be flexible but should be guided

by consideration of a child's age, nutrition and iron

status, and housing age, housing condition, and

population density. The first erythrocyte protopor-

phyrin test should generally occur at the same time

as the determination of the hematocrit, which typ-

ically is performed between 9 and 15 months of age.

Because the prevalence of lead poisoning increases

sharply at 18 to 24 months of age, any child judged

to be at elevated risk of plumbism should have ia

second erythrocyte protoporphyrin test performed

at or about 18 months of age and at frequent

intervals (3 to 6 months) thereafter appropriate to

the degree of risk. Surveillance should continue

routinely up to age 6 years and, if appropriate,

longer.

3. The Academy sidommends that any child, in

whom increased lead absorption or lead poisoning

has been confirmed by venous blood lead determi-

nation, be followed closaly by means of repeat ve-

nous tests. For such children, ‘abatement of envi-

ronmental sources of lead is essential.

4. The Academy notes that some predisposing

factors for lead poisoning, iron deficiency in partie-

ular, are preventable. Pediatricians should make

vigorous efforts to identify and correct iron defi.

ciency, calcium deficiency, and other nutritional

deficiencies, particularly in children from areas of

high lead exposure.

5. The Academy recommends that pediairiclavs

attempt vigorously to educate parents, particularly

parents of children in high-risk populations, about

the hazards of lead, its sources and routes of ab-

sorption, and safe approaches to the prevention of

exposure. :

Recommendations for Public Agencles

1. The Academy recommends that reporting of

cases of lead poisoning to state health departments

be mandatory in all states.

2. The Academy notes that, in the present ap-

proach to screening for lead, inspection of a child's

environment is generally undertaken only when an

elevated blood lead level is found. In effect, children

are used as biologic monitors for environmental

lead. The Academy recommends that this sequence

be reversed. A national program for systematic

screening of lead hazards in housing is overdue.

The enormity of the task favors a stepwise ap-

AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS 463

a

y

—

—

n

e

t

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

proach. Suggested ap hes might include:

screening of oldest houMg, followed by newer

housing; screening of housing in inner cities, then

in less densely populated areas; and targeted

screening of housing with small children.

8. The Academy supports the prompt, vigorous,

and safe abatement of all environmental lead haz-

ards. The US Department of Housing and Urban

Development, state health departments, and local

health departments should require that all hazard.

ous lead-based paint (exterior and interior) be re-

moved from all housing. Development of methods

of abatement, which are safer and more effective

than those currently in use (torches, heat guns, and

sanders) must be given high priority to prevent the

further endangering of lead-poisoning victims. The

US Environmental Protection Agency is urged to

persist in its laudable plan to promptly and finally

remove all lead from gasoline.

4. The Academy urges the US Congress and the

US Department of Health and Human Services to

become fully cognizant of the high prevalence of

childhood lead poisoning in the United States, its

irreversible consequences, and its great human and

fiscal costs. Restoration of funding is urgently

needed for screening, hazard identification, and

hazard abatement.

5. The Academy recommends that state health

departments and Academy chapters exert their

maximum influence to assure that state licensing

agencies permit laboratories to perform blood lead

and erythrocyte protoporphyrin tests only if those

laboratories consistently meet criteria for accuracy

and repeatability as determined by their perform-

ance in interlaboratory proficiency-testing pro-

STAs.

SUMMARY

Patterns of childhood lead poisoning have

changed substantially in the United States. The

mean blood lead level has declined, and acute in-

toxication with encephalopathy has become uncom-

mon, Nonetheless, between 1976 and 1880, 780,000

children, 1 to 8 years of age, had blood lead concen-

trations of 30 ug/L or above. These levels of ab-

sorption, previously thought to be safe, are now

known to cause loss of neurologic and intellectual

function, even in asymptomatic children. Because

this logs is largely irreversible and cannot fully be

restored by medical treatment, pediatricians’ ef-

forts must be directed toward prevention. Preven-

tion js achieved by reducing children’s exposure to

lead and by early detection of increased absorption.

Childho&# lead poisoning is now defined by the

Academy as a whole blood lead concentration of 25

ug/L or more, together with an erythrocyte proto-

464 LEAD POISONING

- ‘ACKNOWLEDGMENT

porphyrin ley 35 pg/dL or above, This defini-

tion does not 6 the presence of symptoms. Jt

is identical with the new definition of the US Public

Health Service. Lead poisoning in children previ-

ously was defined by a blood lead concentration of

30 pg/dL with an erythrocyte protoporphyrin level

of 50 ug/dL.

To prevent lead exposure in children, the Acad. = SF"

emy urges public agencies to develop safe and effee-

tive methods for the removal and proper disposal

of all lead-based paint from public and private

housing, Also, the Academy urges the rapid and

complete removal of all lead from gasoline, |

To achieve early detection of lead poisoning, the,

Acade ends ildren in the

United States at risk of exposure to lead be screens

“for lead absorption at ApproTimataly. 12 months of

“2ge by means of the i Tin

test, when that test is available, Furthermore, the

Academy recommends follow-up erythrocyte pro-

toporphyrin testing of children judged to be at high

risk of lead absorption. Reporting of lead poigoning

should be mandatory in all states. :

Wa are grateful for the assistance of J, Julian CHisolm, Bi

Jr, MD, Jane L. Lin-Fu, MD, Vernon Houk, MD, John :/g&

Stevenson, MD, and John F. Rosen, MD. : "EE

COMMITTEE ON ENVIRONMENTAL.

- HAZARDS, 1984-1986

Philip J. Landrigan, MD, Chairman

John H. DiLiberti, MD

Stephen H. Gehlbach, MD

John W. Graef, MD

James W. Hanson, MD

Richard J, Jackson, MD

Gerald Nathenson, MD

Liaison Representatives

Henry Falk, MD

Robert W, Miller, MD

Walter Rogan, MD

Diane Rowley, MD 3

COMMITTEE ON ACCIDENT AND Pd1sON | Ji

PREVENTION, 1984-1988 :

Joseph Greensher, MD, Chairman |

Regine Aronow, MD :

"Joel L, Bass, MD

William E. Boyle, Jr, MD

Leonard Krassner, MD

Ronald B. Mack, MD

Sylvia Mieik, MD

Mark David Widome, MD

Liaison Representatives

Andre I’Archeveque, MD

PAGE . B28

t

r

-

—

—

—

a

e

.

3

ow

ay

A

a

r

y

-

:

f

s

G

a

.

i

| o

e

C

JH

1

Gerald M. Breitzer®00

Chuck Williams, MD

AAP Section Liaison

Jerry Foster, MD

Joyce A. Schild, MD

ft REFERENCES

Centers for Dissase Control: Burveillancs of childhood lead

poisoning—United States, MM WR 1882;31:132-134

2. Mahaffey KR, Annast JL, Roberts J, et al: National eati.

matas of blood lead levels: United States 1978-1980: Asso-

ciated with selectad demographic and socioeconomic factors,

N Engl J Mud 1882;807:573-579

8, Klein R: Lead poisoning, Adv Pediatr 1077;24:108-132

8

7

+ 4. Annest JL, Pirkle JL, Makue D, et al: Chrondlogical trend

in blood lead levels between, 1976 and 1080, N Engl J Med

1883:808:1873-1877

. Plomall 8, Corash L, Coraah MB, et zl: Blood jaad concen-

trations in A remote Himalayan population. Sciange 1980;

210:1136-1137

Grandjean P, Fjerdingstad E, Nielsen OV: Lead concentra-

tion in mummified nubian brains, Pressntad at the Intsr-

national Conference on Heavy Mstals in the Environment,

Toronto, Canada, Oct 27-31, 1975

Hernbarg 8: Biochemical and clinical effacts and rRBpONEES

as indicated by blood concentration, in Singhal RL, Thomas

J8 (eds): Lead Toxicity. Baltimore, Urban & Schwarzenberg,

Ine, 1880

. Berlin A, Schaller KH, Grimes H, ot al: Environmental

exposure to lead: Analytical and epidemiological investiga.

. tions using the European standardized method for blood

11

12,

18.

14.

15,

16.

12. Centers for Dissage Control: Pray

_-young children. MMWR 1885;34:67-68

delta-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase activity determina.

tion. Int Arch Occup Environ Haalth 1877;38:135~141

_ Piomell §, Seaman C, Zullow D, at al: Threshold fot lead

damage to ham synthesis i in urban children. Proc Natl Acad

Sei USA 1682;79:3335-3338

. Mahaffey KR, Rosan JF, Chesney RW, at al: Association

batwean age, blood lead concentration, and ssrum 1,25.

dihydrozycalcifaro] lavels in children, Am J Clin Nutr

1982:35:1327-1331

Rossn JF, Chesney RW, Hamstra A, et al: Reduction in

125-dihydroxyvitamin Dio children with increased lead

absorption. N Engi J Med 1880;302:1128-1131

Needlernan H, Gunnoe C, Leviton A, ut al: Deficits in

paychologie and classroom performance of children with

elevated dentine lead levels, N Engl J Med 1879;300:885-

695

Winneke G, Kramer G, Brockhaus A, st al: Neuropsycho-

logical studies in children with elevated tooth lead concen-

tration. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 1982:51:169-183

Yule W, Lansdowne R, Millar IB, et al: The relationship

between blood lead concentrations, intelligence and attain-

ment in a school population: A pilot study. Dev Mad Child

Naurol 1881:23:5687-576

Rutter M: Low leval lead exposure: Sources, affects, and

implications, in Rutter M, Jones RR, (ads): Lead vs. Health,

Naw York; John Wiley & Sons, 1883, pp 333-370

Schwartz J, Angle C, Pitcher H: Relationship batween child-

hood blood Jead lsvels and stature, Pediatrics 1986;77:281-

288

venting lead poisoning in

1%; Landrigan PJ, Gehlbach ARSE BF, et al; Epidemic

lead absorption near an ore smelter: The role of particulata

lead N Engl J Med 1975; 292:128-122

18. Assessment of the Safety of Lead and Lead Saits in Food: A

20.

Report of the Nutrition Foundation’s Expert Advisory Com.

Wttee, Washington, DC, The Nutrition Foundation, 1982

Bureau of the Cansus. Statistics! Abstracts of the Unitad

States, 1980, ed 101. Washington, DC, US Department of

Commerce, 1880

21.

22.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28,

30,

aL

32.

33.

8,

35.

Bureau of the colli: Housing Survey, 1978, Cur-

rent Housing reporta series H-150-78. Washington DC, US -

Department of Commerce, 1879

Fischbein A, Anderson KE, Sassa 8, et al: Lead poisoning

from “do-it-yourself” heat guns for removing lead based

paint: Report of two cases, Environ Ras 1981;24:425-431

23. Landrigan PJ, Baker EL, Himmelstein JS, ot al: E

to lsad from the Mystic river bridge: The dilemma of

leading, N Engl J Med 1882;308:873-878 .

Bose A, Vashistha K, O'Loughlin Bd: Azareén por Empa-

cho—Another cause of lead toxicity, Pediatrics 1988.72: 106-

108

Centers for Discase Control: Folk ramedy-aasociated | ad

poisoning in Hmong ¢hildren-—Minnesota, MMWR 18

32:556-666

Ali AR, Smalls ORC, Aslam M: Surma and lead poisoning.

Br Med J 1878;3:815+818

Shaltout A, Yaish 8A, Fernando N: Laad encephalopathy in

infants in Kuwait. Ann Trop Paediatr 1981;1:2080-215

Miller C: The pottery and plumbism puszle, Med J Austr

1882:30:44 2-443

29, Ostarud HT, Tufts E, Holmes M8: Plumbism at the Green

Parrot goat farm. Clin Toxicol 1978:8:1-7

Baker EL Jz, Folland DE, Taylor TA, et al: Lead poisoning

in lead workers and their children: Home contamination

with industrial dust. N Engl J Med 1977:206:260-261

Chisolm JJ Jr: Fouling one's own nest. Pediatrics

1078;62:61 4-817

Ziegler EE, Edwards BB, Jansen RL, ot al: Absorption and

retention of lead by infants. Pediatr Res 1978;12:26-34

Roels HA, Buchet JP, Lauwerys RR, et al: Exposure to lead

- by the oral and the pulmonary routes of children living in

tha vicinity of a primary lead amelter. Environ Res

1980,22:81-94

Bayre JW, Charney E, Vostal J, ot al: House and band dist

as a potential source of c lead exposure. Am J Dis

Child 1974;127:187-171

Charney E, Kessler B, Farfel M, ot al: Childhood ui

poisoning: A controlled trial of the effect of dust-eon

Bees on blood lead levels, N Engl J Med 1083;308:1

109

38. Barltrop D: ‘The prevalence of pica. Am J Dis Chi

37.

1566;112:116-128

Mahaffey KR: Nutritional factors in lsad poisoning, Nutr

Rev 1981:39:353-362

38. Nathan D, Oski F: Hematology of Infancy and Childhood, ed

a8.

40.

41.

42,

47,

AMERICAN ‘ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS

2 Philadelphia, WE Saundars Co, 1881

Yip R, Schwartz 8, Deinard AS: Screening for iron deft-

clancy with tha srythrocyte protoporphyrin test. Pediatrics

1983:72:214-219

Piomelli 8, Rosen JF, Chisolm JJ Jr, ot al: Management of

childhood lead poisoning. J Padiatr 1684;105:523-532

Praventing Lead Poisoning in Young Children, publication

No. 00-2629. Atlanta, Centers for Disease Control, April

1878

Blickman JH, Wilinson R, Grasf J: The isad ling revisited

AJR 1086;74:88-83

Markowitz ME, Rosen JF: Asssssment of lead stotesiin

children: Validation of 8-hour CaANa*EDTA provocative tést,

J Pediair 1884;104:337-341

. Taisingsr J, Srbova J: The value of mobilization of lead by

calcium sthylene diaminetetrancetate in the diagnosis of

lead poisoning. Br J Ind Med 1558;18:148-153

. Chisolm JJ Jz, Baritrop D: Recognition and management of

children with increased lead absorption. Arch Diz Child

1979;64:248-262

Graef JW: Clinical outpatient management of childhood

lead poisoning, in Chisolm JJ Jr, O'Hara D (ads): Lead

Absorption in Children. Baltimore, Urban & Schwarzenberg,"

1882, pp 153-184

Chisolm JJ Jr: Management of increased lead shsorphiott?

Nustrative cases, in Chisolm JJ Jr, O'Hara D (eds): Lead

Absorption in Children. Baltimore, Urban & Schwarzenberg,

1882, pp 172-182 4

FRIGE .

465"

5

DANIEL E. LUNGREN, Attorney General

of the State of California

CHARLTON G. HOLLAND, III

Assistant fsusy paul

STEPHANIE W orl

may General

yi} “hg i fy 12th Floor

i 94612-3042

Pelephone: (415) 464-1173

Attorneys for Defendant

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA WV

O

D

O

w

h

o

r

E

&

I

N

N

ee

11 | ERIKA MATTHEWS AND JALISA ) No. C 90 3620 EFL

§ MATTHEWS, by their ad Hiem Lisa

12 | Matthews, and PEOPLE UNITED FOR A DECLARATION OF RUTH 8.

BETTER OAKLAND, On Behalf of RANGE, MPH. P.HN.

13 || Themselves and All Others Similarly Stinated,

14 Plaintifls,

15 Ya

16 | MOLLY OD Director, Califbrnin

Department of Health Services,

Defendant.

“

a

r

a

t

Me

pt

e

t

ew

“a

”

“a

gr

™

va

nt

’

20 { I, RUTH 8S. RANGE, declare:

21 1. 1hold an M.S, degree in Nursing. I have spent my entire professional

22 { carcer stocu 1958 in the area of public health, 1 have been employed by the State

23 {| Department of Health Services since 1977 as Chief of the Regional Operations Section

24 || of the Child Health and Disability Prevention Branch of the Departinent. As such I

25 { have been significantly involved in lead screening and testing matters within the Jast

26 || decade.

27 2. The matters stated below are personally known to me and if called as a

L

DECLARATION OF RUTH 8. RANGE, M.S. PHN.

JUN 18781 1 180 PAGE . B30

QO

oN

d

C

W

e

W

N

T

I

a

W

y

&

WB

W

w

=

0

9

witness I could and would testify competently concerning vd SRTDE,

3 The Department of Health Services does not dispute the seriousness of

the problem of lead poisoning in children, In fact, as recently as March 12, 1991, the

Department's former Director, Dr, Kenneth Kizer stated that: "Lead poisoning is the

most significant environmental health problem facing California children today, and

ingufficient consideration is being given to this potential problem during routine child

health evaluations™ What the Department docs dispute is whether either the law or

good medical practice requires the actual testing of children’s blood for the presance of

lead in all cases, and particularly very young children in the Early and Periodic

Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment ("EPSDT") Program of the Federal Medicaid

Program (known as tho Medi-Cal program in California, and administered by the

Department of Health Services).

4, The Department belicves that neither applicable laws nor good medical

practice requires that all EPSDT children receive blood lead tests as a part of the

mandatory screening process. Rather, it is the Department's position that young (is.

wnder 6 years old) EPSDT children should first be screensad by their treating physicians

for bath the presence of objective medical indications and/or environmental factors

I which might indicate the possibility of lead taxicity, If cither or both are present the

a blood test would be indicated. While the State Medicaid Manual (Plaintiffs’ Exhibit

N) recommends the erythrocyte protoporphyrin (“EP”) test as the "primary screening

test” (Ex. N, at p. 5-15), this test is falling into disfavor due 10 its relative unreliability

vis-a-vis a blood lead test. (The former is a "pinprick” tat while the latter draws a

sample of venous blood.)

5. A blood test is an intrusive procedure which causcs some degree of

discomfort, and in the vast majority of cases is simply unnecessary to determine

1. CDHPF Provider Information Notice #91-6, inchudad as Exhibit C in the

Exhibits In Support Of Plaindffs’ Motion For Partial Summary Judgment,

2 DECLARATION OF RUTH B, RANGE, M8, PHN.

| »

whether a child is at risk of lead poisoning. Further, there is a significant cost factor

involved in completing a blood test which musi be considered In an age of limited

resources. In Fiscal Year 1989-00 Department records indicate that there were 539,576

children under the age of six in the Medi-Cal program. The cost of an EP test is

$7.50, so the total cost of providing each of these children with such a test would be

$4,046,820. The cost of the moro reliable blood lead test is $22.50, so the total cot of

providing each of these children with such a test would be $12,140,460, |

6. It is the present beliaf of the Department that universal blood lead

testing of young EPSDT children is not medically indicated, legally required nor fiscally

prudent.

W

O

sd

O

h

W

h

B

W

N

e

S

e

No

=

D

I declare under penalty of perjury that the foregoing is true and correct.

Executed at Sacramento, California this 7th day of June, 1991.

: gt i

* » 4

P

e

N

S

A]

N

E

B

R

B

E

3 DECLARATION OF AUTH 4. RANGE, M3, PHN,

TN IE ral 11a a BE CoE