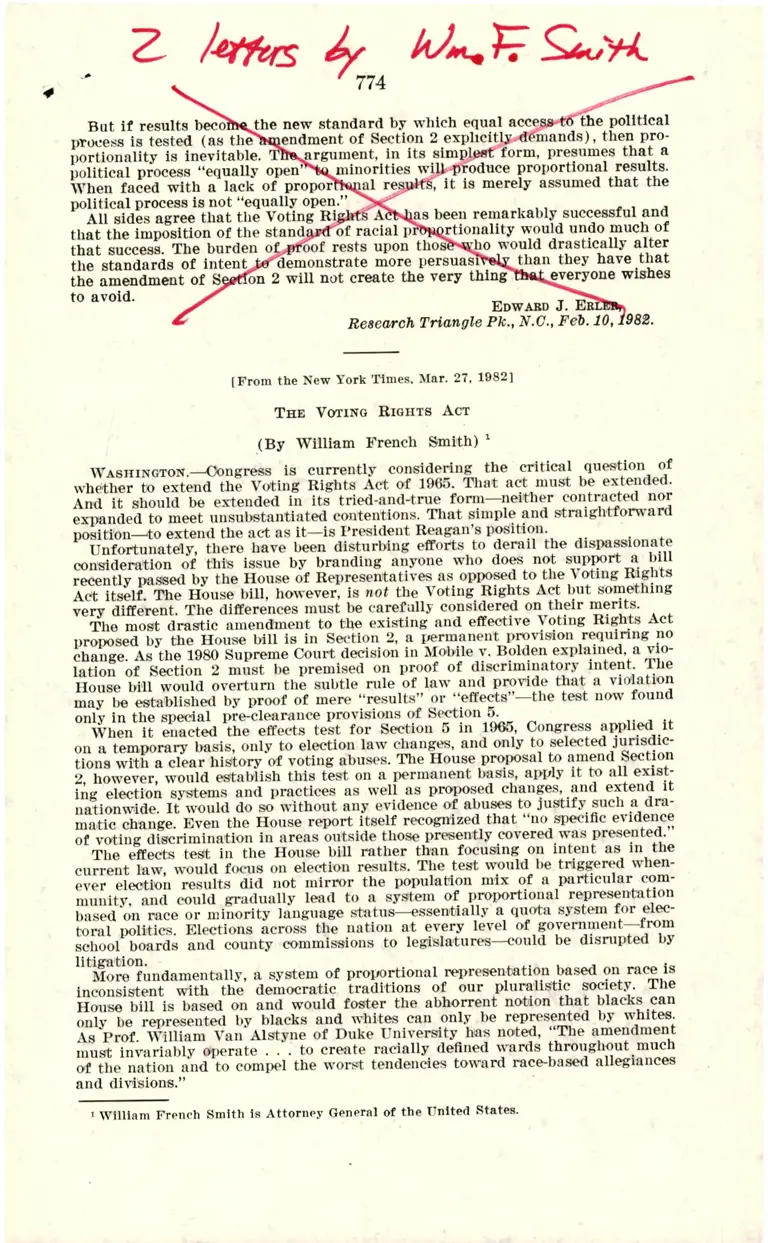

Legal Research on William French Smith Letters

Unannotated Secondary Research

March 27, 1982

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Legal Research on William French Smith Letters, 1982. 49544b20-e192-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c0ec8222-49ab-4b9e-a4b9-8ee40be33475/legal-research-on-william-french-smith-letters. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

But if results beco: ~ the new standard by which equal acce

process is tested (as the . «endment of SectiOn 2 explicit -mands), then pro-

portionality is inevitable. -. argument, in its sim .

political process ”equally open’ .- minorities w' . oduce proportional results.

When faced with a lack of propor - , it is merely assumed that the

political process is not ”equally open.”

All sides agree that the Voting R1_-

that the imposition of the stand 1 of racial p .

that success. The burden o . oof rests upon thos

the standards of intent . demonstrate more persuas

the amendment of S“ on 2 will not create the very thing u. -

to avoid.

-as been remarkably successful and

rtionality would undo much of

'110 would drastically alter

_ - than they have that

everyone wishes

EDWARD J. EB .

Reaearch Triangle Pk., N.0., Feb. 10, 982.

[From the New York Times. Mar. 27, 1982]

THE VorINo RIGHTS ACT

(By William French Smith) ‘

\VASHINGTON.—00ngress is currently considering the critical question of

whether to extend the Voting Rights Act of 1965. That act must be extended.

And it should be extended in its tried-and—true form—neither contracted nor

expanded to meet unsubstantiated contentions. That simple and straightforward

position—to extend the act as it—-is President Reagan’s position.

Unfortunately, there have been disturbing efforts to derail the dispassionate

consideration of this issue by branding anyone who does not support a bill

recently passed by the House of Representatives as opposed to the Voting Rights

Act itself. The House bill, however, is not the Voting Rights Act but something

very difierent. The differences must be carefully considered on their merits.

The most drastic amendment to the existing and effective Voting Rights Act

proposed by the House bill is in Section 2, a permanent provision requiring no

change. As the 1980 Supreme Court decision in Mobile v. Bolden explained, a vio-

lation of Section 2 must be premised on proof of discriminatory intent. The

House bill would overturn the subtle rule of law and provide that a violation

may be established by proof of mere “results” or “effects"—the test now found

only in the special pre-clearance provisions of Section 5.

When it enacted the effects test for Section 5 in 1965, Congress applied it

on a temporary basis, only to election law changes, and only to selected jurisdic—

tions with a clear history of voting abuses. The House proposal to amend Section

2, however, would establish this test on a permanent basis, apply it to all exist-

ing election systems and practices as well as proposed changes, and extend it

nationwide. It would do so without any evidence of abuses to justify such a dra-

matic change. Even the House report itself recognized that “no specific evidence

of voting discrimination in areas outside those presently covered was presented.”

The effects test in the House bill rather than focusing on intent as in the

current law, would focus on election results. The test would be triggered when-

ever election results did not mirror the population mix of a particular com-

munity, and could gradually lead to a system of proportional representation

based on race or minority language status—essentially a quota system for elec-

toral politics. Elections across the nation at every level of government—from

school boards and county commissions to legislatures—could be disrupted by

litigation.

More fundamentally, a system of proportional representation based on race is

inconsistent with the democratic traditions of our pluralistic society. The

House bill is based on and would foster the abhorrent notion that blacks can

only be represented by blacks and whites can only be represented by whites.

As Prof. William Van Alstyne of Duke University has noted, “The amendment

must invariably operate . . . to create racially defined wards through-out much

of the nation and to compel the worst tendencies toward race-based allegiances

and divisions.” -

‘ William French Smith is Attorney General of the United States.

775

Supporters of the House bill are quick to point to a disclaimer clause that

provides that the failure to achieve proportional representation shall not, “in and

of itself,” constitute a violation. This clause would only come into play, how-

ever, after election systems had been restructured to guarantee as nearly as

possible that proportional representation would result. If, once this was done,

proportional representation was not achieved, then and only then would the

disclaimer clause preclude the finding of a violation. The clause simply would

not prevent drastic changes in election systems across the country to facilitate

attainment of- proportional racial representation.

Proponents of the House bill claim that an effects test is necessary because

intent is “impossible” or “extremely difficult" to prove. This is simply false. The

Supreme Court has made clear, on several occasions, that a “smoking gun” is

not required to prove intent. Circumstantial and indirect evidence—including

evidence of efiects—can be relied upon in proving a violation. The Justice De-

partment, for example, just recently intervened in a redistricting case in New

Mexico, maintaining that discriminatory intent can be proved in that instance.

Justice Potter Stewart demonstrated in his scholarly opinion in Mobile v.

Bolden that Section 2 was drafted to enforce the protection of the right to vote

in the 15th Amendment, which has always required proof of intent. The intent

test is the rule in the civil rights area, not the exception. The equal protection

clause of the 14th Amendment, for example, under which so many historic civil

rights advances have been made, has the same intent test. As former judge and

Attorney General Grifl’ln Bell has written to the Senate subcommittee considering

the question, overruling the Mobile decision by statute would be “an extremely

dangerous course of action under our form of government.”

This Administration wholeheartedly supports a 10-year extension of the Vot-

ing Rights Act in its present form. The act is not broken, so there is no need to

fix it. It should be extended as is.

[From the Washington Post, Mar. 29. 1982]

VOTING RIGHTs ACT: EXTEND IT as Is

(By William French Smith)1

On March 20, The Post published the latest in a confusing series of editorials

on the appropriate test for challenging election systems under Section 2 of the

Voting Rights Act. The existing act, which the Reagan administration believes

should be extended, requires proof of intent to discriminate. A bill that has passed

the House, however, would change the Voting Rights Act and focus not on intent

to discriminate but on “effects" or “results." Numerous authorities and com-

mentators have expressed deep concern that a “results” test could gradually im-

pose a system of proportional representation based on race—a quota system for

electoral politics. Judging by its own editorials. the response of The Post to this

concern is: yes, no, maybe.

In its April 1980 decision in Mobile 1'. Bolden, the Supreme Court explained

that Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act required proof of discriminatory intent.

In that case, Justice Potter Stewart warned that the theory of the dissenting

opinion. which embraced the results test, “appears to be that every political

group, or at least every such group that is in the minority, has a federal con-

stitutional right to elect candidates in proportion to its numbers."

The Post agreed with Justice Stewart’s concern. On April 28, 1980, it con-

cluded that the court was correct to reject challenges based on the results test.

“By opting for intent,” The Post reasoned. the court “has . . . avoided the logical

terminal point of those challenges: that election district lines must be drawn to

give proportional representation to minorities."

On Dec. 20, 1981, however, The Post changed its tune. It then supported the

recently passed House bill to overturn Mobile. The Post rejected President Rea-

gan’s expressed concern that the results test could mandate proportional repre-

sentation. It does not do so. but in any case, if proportional representation is the

“logical” end of the results test, as The Post claimed, it is difficult to see how

any disclaimer clause can be effective. The disclaimer either completely repeals

the results test, or is meaningless. The Post nonetheless urged the president to

“stop objecting and join the celebration."

1 The writer is attorney general of the United States.

776

11 Jan. 26, 1982, The Post again editorialized in support of the House bill,

claoiming now that the bill would merely return. the law to where it had been

before Mobile change it—and citing cases that did not support that proposition.

As The Post explained in yet another editorial, on Feb. 11, “we believe Mobile

set a new and unnecessarily tougher standard for the courts to use in determin-

ing whether a particular system is discriminatory.” The Post’s original edi-

torial—the one that agreed with the [Mobile] decision—somewhat oddly made

no reference to this supposed “change” in the law. This suggests the new argu-

ment that Mobile changed the law is a hastily devised smokescreen to obscure

the dramatic change proposed by the House bill.

In its latest editorial effort, on March 20, The Post brands my expression

of concern that the results tests could lead to proportional representation—its

own argument at one point—as a “scare tactic.” But, at the same time, it

acknowledges that no one wants proportional representation and urges House

bill supporters to “take whatever steps are necessary to reassure undecided

senators” that proportional representation—according The Post, the “logical

terminal point” of the results test—will not be compelled by that test. Perhaps

The Post is beginning to recognize—as it once did—that the results test could

lead to proportional representation. At least The Post is no longer facilely

urging those with such concerns to “stop objecting and join the celebration.”

The Post contends, however, that it is ”almost impossible" to prove intent——

even though the intent test is the standard test in civil rights law and many

other areas as well, and is often met in the courts. According to The Post, the

House bill ”would allow the courts to look at a number of factors—history of

discrimination, nominating procedures, election results, responsiveness of elected

officials.” As Justice Stewart made quite clear in Mobile, however, that is al-

ready true under the intent test. A “smoking gun” is not required and intent

may be proved by indirect and circumstantial evidence, including evidence of

the sort cited by The Post.

There is of course nothing wrong with the situation in which freely cast votes

happen to elect minorities in proportion to the number of minorities in the elec—

torate. What is disturbing, however, is a legislative effort to compel reorganiza-

tion of electoral systems to guarantee such a result, on the basis of the abhor-

rent notions that blacks vote only for blacks and whites only for whites. As a

society, we have moved well beyond that.

This administration fully supports extension of the Voting Rights Act—for an

unprecedented 10 years. The Post, by contrast, supports the House bill and

changes in the act. Congress has a choice. It can continue the protection of the

most successful civil rights law ever enacted, or it can embark the nation on

a per1lous and divisive experiment with a new standard. The right to vote is

too important to be subject to such experimentation.

We are pleased that The Post is urging Congress to take whatever steps are

necessary to guarantee that proportional representation is not compelled. The

best way to do that is to extend the act as is.

[From the New York Times, Mar. 19. 1982]

HARDBALL VOTING-RIGHTS HEARINGS

(By John H. Bunzel) ‘

-. Id most members of Congress favor e_, ' - ng the Voting

‘ g its basic protections and g e Entees. But many of

‘ of the law take issu /t'h parts of the House-

- a1 require/v s that would give assistance

i1 0 ’/ standards by which an electoral

.. om coverage but which many believe

President Reagan

Rights Act and m‘aintal

the most enthusiastic frie

passed bill—for example, the b

resident of San Jose State Unlversitv. is a senior r- .

tution. He testified at the Senate Judiciary subcommi

~: rch fellow at

. Inst ’ hearings

in February.