Brief of Defendants in Support of Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law and the Board's Detroit Plan

Public Court Documents

May 8, 1972

20 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Brief of Defendants in Support of Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law and the Board's Detroit Plan, 1972. a45e69f4-52e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c1d4daab-da18-4bf4-b83f-0c82ee519399/brief-of-defendants-in-support-of-proposed-findings-of-fact-and-conclusions-of-law-and-the-boards-detroit-plan. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

#

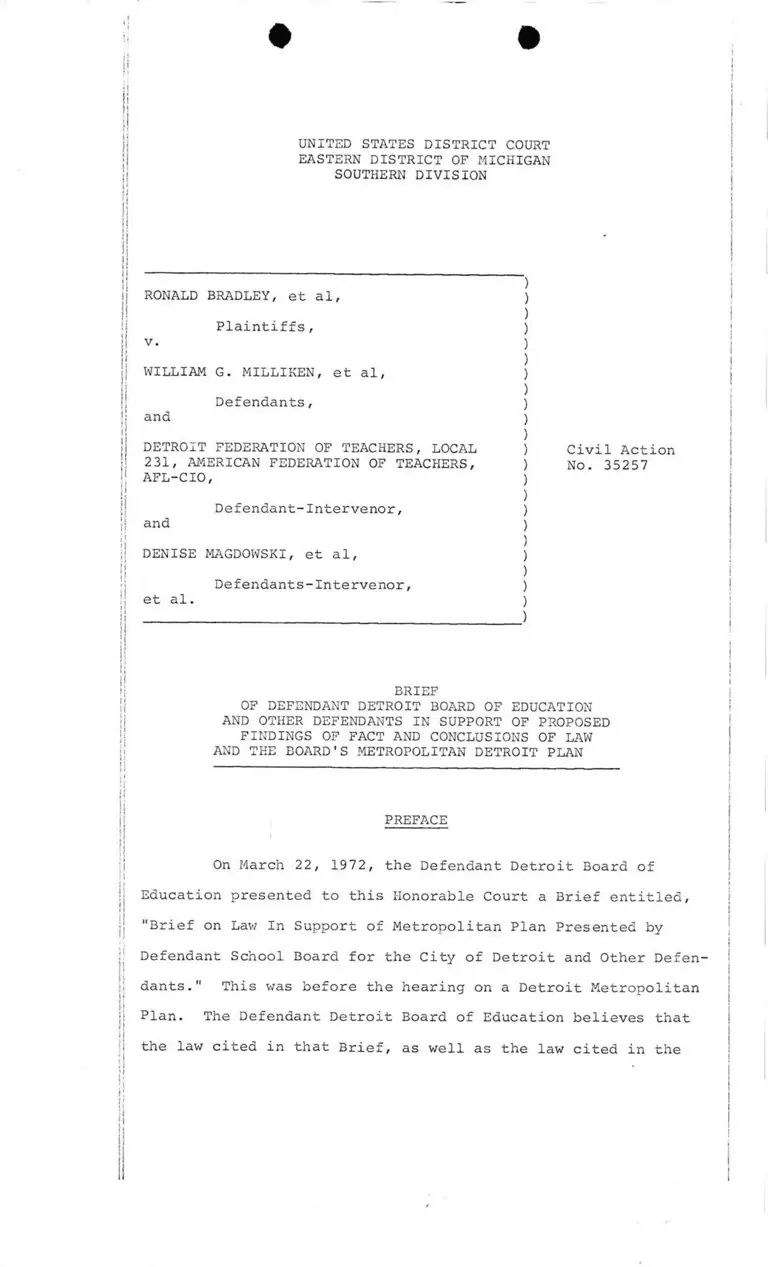

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

'

i■

i

)RONALD BRADLEY, et al, )

)Plaintiffs, )

v. )

)WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al, )

)Defendants, )

and )

)DETRO±T FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, LOCAL )

231, AMERICAN FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, )

AFL-CIO, )

)Defendant-Intervenor, )

and )

)DENISE MAGDOWSKI, et al, )

)Defendants-Intervenor, )

et al. )

)

Civil Action

No. 35257

BRIEF

!j OF DEFENDANT DETROIT BOARD OF EDUCATION

AND OTHER DEFENDANTS IN SUPPORT OF PROPOSED

FINDINGS OF FACT AND CONCLUSIONS OF LAW

AND THE BOARD'S METROPOLITAN DETROIT PLAN

jl . PREFACE

;!

On March 22, 1972, the Defendant Detroit Board ofil

!! Education presented to this Honorable Court a Brief entitled,

jj "Brief on Law In Support of Metropolitan Plan Presented by

I; Defendant School Board for the City of Detroit and Other Defen-I '

!j dants." This was before the hearing on a Detroit Metropolitan

|| Plan. The Defendant Detroit Board of Education believes that

II

|| the law cited in that Brief, as well as the law cited in the

:

iI

i

Board s ODjecuions to the Defendant State Board of Education

plans filed on March 4, 1972, is applicable and applies directly

to the evidence elicited in the hearings on the Detroit Metro-

tan Plan. therefore, the Defendant Detroit Board of Educa

tion herein incorporates said Briefs and has attached for the

Court's convenience a copy of said Briefs to this Brief as

Appendices A and B. This Brief is designed to highlight certain

salient facts and law which we believe will be helpful to the

Court. In summary, the Defendant Detroit Board of Education

takes the position that its Metropolitan Desegregation Plan is

entitled to preference and should be adopted by the Court

because (1) it desegregates; (2) does not lead to resegregation;

(3) it is educationally sound; (4) and it is practical as it

was developed by educators, both white and black, who are

intimately familiar with metropolitan Detroit's educational

problems, logistics and demography.

I. AN ACCEPTABLE PLAN OF DESEGREGATION SUBMITTED

BY THE DEFENDANT DETROIT BOARD OF EDUCATION IS

ENTITLED TO PREFERENCE OVER ANY OTHER PLANS

SUBMITTED.I!!u .If it be conceded that this Court was correct in itsh

|i finding that the Defendant Detroit Board of Education and the

i .

i| State of Michigan have deliberately segregated students within

jj

j Detroit, both the Defendant Detroit Board of Education andi

| Defendant State Board of Education have an affirmative duty

j to come forward with acceptable desegregation plans. The

I District Court then has the duty to evaluate those plans "in

| light of the facts at hand and in light of any alternatives

j which may oe shown as feasible and more promising in their

I! effectivenss. Green v. County School Board of New Kent County,

-2-

!

!!

i

391 U.S. 430,439 (1968). Nevertheless it is settled that the

initial duty to prepare and to propose a plan is on the Detroit

School Board, not on the Court or the Plaintiffs. Clark v.

i! .jj Board of Education of Little Rock School District, 4'26 F.2d— — - -------

|j 1035-1045 (8th Cir.1970) , cert. denied, 402 U.S.952 (1971) ;

I I

| Gordon v. Jefferson Davis Parish School Board, 315 S.Supp.901,

S 002, fn.1(W.D.La.1970), vacated on other grounds, 446 F .2d 266

(5th Cir.1971). When the board's plan offers effective relief,

| should oe adopted, recognizing that the details of a const!—

j tutionally acceptable plan should be left to the body that must

| admxnister it. Allen v. Asheville City Bd. of Educ.,434 F.2d

| .i 002 (4th Cir.1970); Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 325 F.I |

J Supp.828,832.33 (E.D. Va.,1971); Green v. School Bd. of City

i| _Roanoke, 316 F. Supp. 6 (W .D . Va . 19 70) , affirmed in part, vacated

in part on other grounds, 444 F.2d 99 (4th Cir.1971); Moore v.

j Tagipahoa Parish School Bd.,304 F.Supp. 244 (E.D.Lal969), appeal

| dism.,421 F.2d 1407 (5th Cir.1969).

I J

The Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit has stated: 1

j! „ . . . :ii Tt 1S initially the responsibility of the Board of Education to !

................................................................. , !j prepare a feasible means of disestablishing existing segregation i

. . . !and eliminating its effects within the school system. Ordinarily,

j uhe Court will not substitute its discretion for that of a board

jj °f education but will adopt a plan proposed by the board if it

jj fulfills the Court's duty to eliminate the effects of past

Siij illegal conduct." Davis v. School Dist. of City of Pontiac,

i 443 F .2d 573,577 (6th Cir.1971), cert.denied, 404 U.S. 913

h (1971). See also Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ.,

ij 306 F.Supp.1291,1297 (W. D . N . C . 19 6 9 ) .jl

The effectiveness of a plan has been defined by the

| Supreme Court in two complementary ways. "Where the Court

j finds the board to be acting in good faith and the proposed

i| plan to have real prospects for dismantling the state-imposed

Ij _j! dual system 'at the earliest practicable date, 1 then the plan

; may be said to provide effective relief." Green v. County School

! Board of New Kent County, supra. -

In the absence of a single school board with operating

responsibility for the entire area, the Court should first

j consider any plan proposed by the State Board of Education, but

)

j the Michigan State Board of Education has declined to advocate

| anY Plan it has submitted. As the State Board is unwilling to

j

j! represent to the Court that any of its plans is desirable or

j;|| will be effective, none is entitled to the deference that stems

j . .| from administrative responsibility and preference. There being

| no other body governing the whole area, the plan of the Defendant

j Detroit Board of Education is entitled to the deference it wouldJI . . _ .! receive lr a Detroit-only plan were contemplated. The DetroitI

| Board, equally with the State Board, has an affirmative dutyi

to propose a plan. Unlike the State Board, it has done so. It

|j earnestly asserts the superiority of its Metropolitan Plan over

jj all other plans suggested. Furthermore, the Detroit Board is

ji responsible for educating far more children than any otherj{J

jj board in the metropolitan area — and no other board has suggested

a plan for the metropolitan area. Because of its central role

;

in any metropolitan plan and its experience in guiding the fourth

largest district in the country, the Detroit Board is keenly

| aware of many of the operating problems to be encountered in|

i the various plans under consideration. Its expertise and pivotal

* iji position entitle its views to the same respect as if it werei ̂ .jj going to operate the entire plan directly.

:

Furthermore, there is no question the Detroit BoardI

j of Education Metropolitan Plan is offered in good faith. The

-4-

jl!iM

j candor and helpfulness of the Board's staff members who have

ti , .I testified in the last few weeks is clear evidence of the Board'sj

j! good faith in proffering its Metropolitan Plan.

J

1

THE ACCEPTABILITY OF THE DEFENDANT DETROIT BOARD

OF EDUCATION'S METROPOLITAN PLAN IS HIGHLIGHTED

BY THE FACT THAT IT WAS DRAWN BY EDUCATIONAL

EXPERTS WHO ARE FAMILIAR WITH THE METROPOLITAN

DETROIT SITUATION.

It should be noted that the plan put forth by the

I| Detroit Board was based on a substantially greater amount of! '

data, and was done with significantly more thoroughness than

; the other two plans submitted to the Court. This is no reflectio

!ij whatsoever on the skill and industriousness of those who authored

| and advocated the other plans, it merely illustrates that the

| operating Board of Education is the best equipped to draw a plan,

jj

I and demonstrates the wisdom of the rule giving deference to the!

j Board plan. Both authors, Drs. Morshead and Foster, admitted

| that the Board had used data, particularly SES data, that they

■

| felt was properly included, but which they did not have avail-

j able at the time they drafted their plans (Morshead, Metro Tr.I(| 45; Foster, Metro Tr.1210). Dr. Foster admitted a lack of famili

\

[ arity with the metropolitan area, indicating that one judgment

1

j involving the exclusion of a particular school district, Utica,: I! jj! from his plan had been made on the mistaken assumption thatj !

jj the district was not served by an expressway (Foster, Metro Tr.

i!ji 1220-4). Under these circumstances, it only makes good sense

iji to defer to the superior knowledge and data base of the Defendantj

it Detroit Board of Education.

-

-

III. OF THE PLANS SUBMITTED, THE DETROIT BOARD'S

METROPOLITAN DESEGREGATION PLAN BEST MEETS THE

THREE ELEMENTS NECESSARY FOR A CONSTITUTIONALLY

ACCEPTABLE PLAN AND FOR THIS REASON, SHOULD BE

ADOPTED BY THE COURT.

-5-

At Page Two of the Defendant Detroit Board of Education's

jjBrief of March 22, 1972, we wrote as follows:

"At least three elements must be present

for a plan to 'work'. (1) Every'school,or

almost every school, should contain a mixture

of the races that roughly approximates the

makeup of the student community as a whole.

I Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ.,

402^U. S . 1,91 S .Ct.1267, 1280—81 (1971); Davis

1 v. Board of School Comm'rs of Mobile CountvT

402 U.S. 33,91 St.Ct. 1289 at 1292” ( 1971) /

(2) The plan should be educationally sound. See

5wann, supra, 91 S.Ct. at 1283. (3) The

plan should avoid resegregation. Lemon v.

Bossier Parish School Board, 446 F.2d 911

(5th Cir. 1971) . . . 751

A- lhe racial mix desegregation. Not only does the

j Detroit Metropolitan Plan contain a mixture of the races that

roughly approximates the makeup of the metropolitan Detroit

i student community as a whole, pursuant to Swann and Davis, but

j! •*-s the only plan advocated to the Court which desegregates

I the community, leaving no court-sanctioned racially identifiable

| schools.!!

We invite the Court's attention to Defendant Detroit

ii .•: Board of Education's proposed findings of fact Nos. 1 through 7

!! .I which clearly establishes that the Detroit metropolitan community

is Wayne, Oakland and Macomb Counties. To again make reference

to the testimony of Dr. Roger Marz, there are networks of trans

portation, commuting patterns, shopping patterns, distribution

i areas, absence of geographic barriers, and regional government

j

|cooperation, clearly establishing that the natural metropolitan

j Detroit community is Wayne, Oakland and Macomb Counties (City

j Tr.207) .

j In the metropolitan Detroit community, there are

| some 962,627 students of whom 237,957 are minority students.

This means that in the student community, 24% of the students

1/ iare minority students (See Def.Ex.DM-11 and DM-14) . The

i

clusters presented by the Defendant Detroit Board of Education j

vary, excluding clusters Nos. 12 and 18 from 19.7% (cluster No.l)

to 29.8% (cluster No.8) of minority students. The average percent

of the minority student in the clusters, excluding clusters Nos.

12 and 18, is 24.53%. Therefore, quite clearly, the Detroit

clusters meet the constitutional requirements of Swann and Davis

and do furnish the required racial mix that approximates the makeup

of the student community as a whole.

Cluster 12 and 18 are admittedly below the average

because of the lack of minority students in those particular

geographic areas. If clusters Nos. 12 and 18 were deleted from

the Plan, there would be a total of 855,332 students of which

226,430 are minority students. This would mean that the metro

politan community would consist of a 26% minority. The clusters,

as presented by the School Board approximate the racial mix of

the metropolitan student community.

The clusters, by adopting a racial mix that approximates

the metropolitan community and by including the entire community

eliminate unconstitutional racially identifiable schools. See

Green v. County School Board, 390 U.S. 430, 20 L.Ed 2d 716, 88

S.Ct.1689.

The plan of the Detroit Board succeeds in this regard

where the plans proposed by Plaintiffs and Defendants-Intervenors,

Denise Magdowski, et al, both fail. Both of those plans exclude

from consideration a number of school districts which the record

jl/ As a convenience to the Court, copies of Exhibits DM-11

DM-14 are attached hereto as Appendices C and D.

-7-

• •

; evidence clearly shows are an integral part of the metropolitan

1 conimunity. Examples of such districts are Utica, Walled Lake,

j Plymouth, Woodhaven, Trenton and Grosse lie (Finding of Fact

j| #30)- These districts are virtually all-white, and,' as the

| Detroit Board has shown, are so located that they may exchange

| students with the City of Detroit without unduly disturbing

I the public convenience and necessity (Finding of Fact #32-3).

j To allow these districts to remain all white is to allow segre-

|| .

|j Uated white enclaves to continue to exist within the Detroit

|

| metropolitan community. Were Plaintiffs' plan to be adopted,

schools in these districts would, by action of the Court, remain

racially identifiable as white. There would then be a fragment

| of the metropolitan community which remained segregated and the

i .

| dictate oi Davis to provide the maximum possible desegregation

j! would not have been met.

1|

The Detroit Board has made clear that for educational'

! , .

reasons it is important that these districts be included, due

to the extremely valuable contribution they make to the socio

economic status mix of the community (Finding of Fact #15-18)

| t *

|jHowever, the Detroit Board agrees with Plaintiffs that the

| socio-economic status of these districts is not the ultimate

| constitutional determinent of whether or not they should or

j I

| should not be included. For instance, the Detroit Board has

i suggested the inclusion of the very high socio-economic

i j . . ' I

! status district of Ann Arbor for the simple reason that Ann

I hrbor is not properly considered a part of the Detroit metro-i

i pditan community. The basic reasons that the districts in

II , _|question must be included is that they indeed are a part of

that Detroit metropolitan community and the failure to include

them would mean that they would remain segregated white

jj enclaves sealed off from the rest of the community (Finding

:

}

f;

of Fact #34-6). The additional fact that they are of high

socio-economic status underscores and re-emphasizes the educational

importance of including them, and demonstrates that the constitu- !

tional injustice of excluding them would be paralleled by the

economic injustice which would exist if wealthy districts were

allowed to remain outside the plan simply because their residents

had been able to afford to move further from the City of Detroit

than others not so economically fortunate.

Desegregation. If such unconstitutional white!

| enclaves were permitted to exist, they would provide an open

| invitation to resegregation (Finding of Fact #30). It is a

cardinal principle in school desegregation suits that school

board officials have the duty to fully eradicate the vestiges

! of segregation. Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little Rock Schoolj - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

| 426 F.2d 1035 (8th Cir.1970). As a result, the Fifth

|j Circuit has taken the position that school authorities must

I Cake steps to prevent resegregation by various means. Lemon

| ^ m Bossier Parish School Board, 446 F.2d 911 (5th Cir.1971) .

»

Indeed, it was this problem of resegregation that

caused the District Court on motion by the school board in

Richmond to adopt a metropolitan desegregation plan after a cityI

desegregation plan had failed. See Bradley v. School Bd. of the

City of Richmond, slip op.at p.66.

Certainly, it would be imprudent to suggest that

|j any psrirnster for any plan would provide an iron-clad guarantee

j j Chat the phenomenon of resegregation will not occur to some

|j degree. There always has to be a boundary line somewhere, andi

• j Chere is always going to be someone who lives close enough to

! it, and nas the resources to do so, who will move across it.

-

-9- i

.

!

<

!:I Defendant Detroit Board of Education makes no claim that the I

Detroit Metropolitan Desegregation Plan will prevent resegregation’,

but suggests that it will minimize it substantially more than

the other plans advocated. -

i!<

.

■

i

The key difference in the possibility for resegre

gation between the Detroit plan and the Plaintiffs' plan is that

the Detroit plan includes, within clusters exchanging students

with Detroit, these recently developed suburban areas which are

attractive to persons of high socio-economic status. There

jremains little dispute that it is the middle class which is the

most likely to be both motivated and to have the resources to

change residence due to the presence of blacks in the school.

Plaintiffs' plan leaves a number of inviting areas which are

currently attractive to high SES whites to which such a move

could be made (Finding of Fact #29-34).

Moreover, since these areas, such as Utica, Plymouth,

Trenton and Grosse lie are commuting suburbs, high SES whites

could move there without sacrificing any of the benefits of

residence in the metropolitan community which they now enjoy

(Finding of Fact #29-34). It is one thing to suggest that some I

dissident whites might leave the community because of desegregation;

it is another entirely to provide a large number of places in

which whites could seal themselves off from desegregation without j

sacrificing any mobility within the metropolitan area whatsoever.

It is this last circumstance which describes Plaintiffs' plan,

and which allows it to be fairly described as an unconstitutional j

open invitation to resegregation.

C. Educational Soundness. No desegregation plan can

"work" within the meaning of Green unless it is educationally

’ ::

-10-

| sound. See Bradley v. School Bd. of the City of Richmond, F.

Supp.____ (E.B.Va Jan.5,1972) slip op.p.249-50. The educational

soundness of an integration plan depends on its ability to give

children an opportunity to have stable,mutual, multi-racial

|

! experiences in non-racially identifiable schools.

i

The equal protection of the law with which this

case is concerned is the right of equal access to educational

| opportunity. It profits no one, especially Plaintiffs, if in

i

the process of desegregating the ability of the schools to

deliver educational services is diminished.

The record evidence is clear that the ability to

deliver educational service is significantly dependent on the

SES mix within a particular school (Finding of Fact #16). The

ability to maintain a favorable SES mix throughout all of the I

j schools of the community is dependent on the presence within

i

the schools of all economic segments of the community. Obviously,

if substantial numbers of high SES children are artifically

|

| excluded, the SES mix will, to some degree, suffer.1|

This simply underscores the necessity to drawing a

! P^an which includes within it the total community. If a substan-

1

j tial portion of the high SES areas of that community, which

| happen to be at its periphery are excluded, the educational{ ’ i

! soundness of the plan will be diminished.

|

Plaintiffs tacitly recognize this when they propose j

j Jl ho reach beyond the perimeter proposed by Defendants-Intervenors

and include the extraordinarily-high SES districts of Bloomfield

Hills and West Bloomfield (Finding of Fact #29). Yet, apparently

satisfied with the symbolic inclusion of these wealthy suburbs,

-11-

they fail to include a host of others which are no further distant!

:i _ !

| from Detroit. It should be remembered that Defendant-Intervenor'sj

i . . . !j plan was specifically designed to include districts equi-distant i

|

from Detroit (Flynn, Metro Tr.946). If it is practical to include-

Bloomfield Hills, it is certainly practical to include the other I

. ihigh SES districts no further from Detroit such as Utica, Chippewa!t

Valley, Plymouth, Trenton, Woodhaven and Grosse lie.

I 1

it would be as gross an oversimplification to assume j

| that a favorable SES mix insured educational soundness, as it

would be to assume that a pupil assignment plan alone insured

| desegregation. The Detroit Metropolitan Desegregation Plan is

!

| addressed at some length to a series of other considerations!

| which are of great importance. These need not be discussed at

| length, for there has been no serious disagreement with the

statements made by witnesses of the Defendant Detroit Board of* '

Education (Finding of Fact #46). Suffice it to say that a plan

which fails to provide for the prevention of intra-school

j resegregation, through "tracking" or testing, which fails to

insure that steps will be taken to provide black youngsters going

j to school in the suburbs with a teaching and administrative

staff which is responsive to their needs, needs which that parti

!

cular school may never have had to meet, and which fails to

provide for the full participation of the community in the devel

opment of multi-racial learning environments, is highly unlikely

to ever go beyond mere pupil assignment to the production of true

| equal educational opportunity.

!

i 1i

! IV. DEFENDANT DETROIT BOARD OF EDUCATION'S METROPOLITAN

PLAN INVOLVES REASONABLE AND EDUCATIONALLY ACCEPTABLE

TRANSPORTATION TIMES, ALL WITHIN TRANSPORTATION

TIMES CURRENTLY IN EFFECT IN THE DETROIT METROPOLITAN

AREA •

i

I -12-

,

!

j Metropolitan hearings with regard to transportation times, much

I

jl of way of allusion of the State Defendants and suburbanII| j

Defendants-Intervenors that the travel burdens imposed by any

metropolitan plan would be unduly severe.

!

i, j

Tne record does not support this allusion. While there

is no direct testimony in the record as to a particular magic

number of minutes on the bus at which point bus transportation

becomes burdensome to the educational process, the Defendant

Detroit Board of Education would submit that sound educational

practice has been defined by the actions regarding busing which

have been taken by suburban districts. The Transportation Survey

filed pursuant to the Order of the Court by the State Defendants

! . . _| is most revealing in this regard. It shows that in a number of

! districts one-way transportation times of over an hour are now

j

; in operation, and that in fact, there are some youngsters in the

i metropolitan area who now spend one hour and forty—five minutesi .....

| on a school bus every morning. It is of special interest that

|

!| these lengthy bus rides are not limited to the outer periphery

Ij .

|| of the community. Birmingham and Farmington, both "close—in"

•;i suburbs, record one-way runs of close to one hour. Roseville, a

well-established community in southern Macomb County, records

two sixty-minute one-way runs for pre-school Headstart programs.

Hazel Park, a district adjacent to the City, records

|a sixty-minute one-way run taking students to its vocational

i skills center, meaning rhat this time is in addition to time

I

j| spent getting students from home to school.

A few moments spent leafing through this survey shows

that the notion that bus rides of forty or fifty minutes, or

indeed of forty or fifty miles, in the Detroit metropolitan

There has been much discussion in the course of

-13-

j

I I

i community, are something novel and abhorrent is largely a myth.

J

If it is educationally acceptable to bus a child seventy,

ninety, or one hundred-five minutes every morning for the purpose

of serving the convenience and economy of a local school district,

surely it would be educationally acceptable to expend the same

amount of time for the purpose of providing that child with a

constitutionally required, desegregated education. As noted by the

Supreme Court in Swann, when the time of bus rides compares

favorably with the bus times currently in effect, there is

no reason that busing cannot be used as a tool of desegregation.

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ.,402 U.S. 1,30,23 L.Ed

554,574-575. We further note that Detroit-area black student,

Stephen Scott, and white student, Richard Shapero, ride a school

bus from inner-City Detroit (Scott) one hour and forty-five

minutes, respectively, each way with students as young as three

years of age and find no educational disadvantage in doing so

(Scott,Metro Tr.382; Shapero, Metro Tr.392).

This is by no means to say that the Defendant Detroit

I Board of Education's Metropolitan Plan proposes to transport

| children for times even approaching ninety or one hundred-five

j

j minutes one way. The evidence indicates that the greatest

i distances in each cluster would entail about,at the most, fifty-j .

j five minutes. Plaintiffs' Exhibits show that the very great

|| majority of students included within the Detroit Board clusters

I ,

j which interchange with Detroit are within fifty minutes of the

j '

j far reaches of downtown, and are, therefore, even less distant|

| in time from their assumed destinations in their cluster. Record

» evidence that travel times under the Detroit plan even begin to

approach maximums which now exist in this metropolitan community

simply does not exist.

I

Several parties have attempted to demonstrate that bus

times under the plan would have to be in addition to times which

{

youngsters currently spend on the bus, as they would need to

be collected for the purpose of aggregating a busload for1 ' I

j interdistrict transportation. This logic rests on the assumption i

that the existing transportation pattern now current in each

district would remain as it is now. That does not necessarily I

follow. For instance, even if school collection points are

i •j used, there is no reason why the school used must be the one

which a given student now attends; for instance, secondary student's|

who may attend a more distant high school could be collected

at neighborhood elementary schools, or children, for whatever

j reason, who now do not attend the school closest to home might

jl

|j meet the bus at a more nearby school.

|

Secondly, it is not necessary that in every case, each

| school bus must be loaded with students from one particular

! . . . ! i| school district. For example, if it were more convenient to run j

| a bus down a north-south artery toward Detroit which passed

i j

| through several school districts rather than having that bus

i . . |

I circulate east to west through a single school system before

i . . jheading south, there is no reason, given the fact that the

clusters follow arterial highways, that it could not be done.III :Jl .

Thirdly, in many instances it would be possible to bus

I .| children on a "first in-first out" basis. If the bus, beforei

1 traveling between Detroit and the suburbs had first to make a!!: loop, or circular route to collect the busload, there is noi

| reason the loop could not be traversed clockwise in the morning

Ii and counter-clockwise in the afternoon, meaning that no youngster

jj would have to ride around the loop more than once in a given

I school day.

■

; These are just examples of ways in which bus times

| . . . ' could be optimized in a Metropolitan Plan. The assumption that

any inter—district bus trip is in addition to existing trans—

| P°^tation time simply is not supportable. - What is supportable is

! the assumption that children who live within acceptable driving

! : , ,j time distances of any school to which they might be sent under

!| the plan can be at that school within that acceptable time.

Inasmuch as the record supports the conclusion that

bus times proposed within the plan are and can be within

acceptable educational limits, there is no legal basis for

|| excluding those school districts which Plaintiffs would excludeu

from the plan adopted. As the districts involved are clearly

part of the community, there is every constitutional reason to

include them. As they represent a most affluent sector of thei

I community, particularly Utica, Plymouth, Trenton and Grosse lie,i | ' !

|| anĉ their exclusion would cause substantial educational detriment !

|| . 1 jj to the plan, there is excellent reason for supporting the educa-

|| tional judgment of the Defendant Detroit Board of Education!) !. s

that the benefit to be derived throughout their community from

their inclusion is worth the extra five minutes on the bus, (Rankini,i

Metro Tr.l412(a).

THE DETROIT BOARD PLAN IS THE MOST PRACTICAL

PLAN SUBMITTED TO THE COURT.

The three plans advocated to the Court do not vary

i significantly in terms of the device suggested for the mixing

I . *of students; namely, the establishment of pupil assignment

patterns which create racial balance. This is preciselv the

form of mixing device sanctioned in Swann, and really requires

no further comment.

-16-

|

| suggested by which final detailed pupil assignment plans are to

be created. Plaintiffs, although not precise about this point, j

seem to favor some central body or authority which would be

- responsible for drawing a pupil assignment plan for the entire

. I

metropolitan area. Defendants and Defendant-Intervenor disagree,

both indicating that it is essential that there be intensive

| involvement in the detailing of any plan by all local school

| . Ii drstricts effected.

!I

! xhere is ample justification for this latter approach,

ji both as a matter of law and as a matter of the practicalities

jl the situation. For just as the Defendants here were entitled

iI| to deference to their judgment in determining what should be done

at this juncture, so should every affected school district be

i shown deference in the drawing of pupil assignment plans for

I ' !j their particular district. It is, after all, the people who now j

J . . I« operate the schools who are going to have to continue to operate

I ,

| the schools. The record is clear that the large delegation of

: authority to them by the State leaves the local districts as the

only bodies possessed with the necessary knowledge to draw a

plan which has the best chance to preserve and create educational j

quality. To cut off their right to participate in the creation

!| the plan in detail is to cut off a great deal of the assurance

j that the plan will be educationally successful.

Where the plans differ is in the methods which are

In addition, this Court is properly concerned with the

acceptance of any plan by the community. While it is beyond

argument that lack of community approval of the desegregation

process is no reason to refrain from desegregating, on an occasion1

when the Court is faced with options one of which will substantially

improve the measure of community acceptance, and therefore, the

-17-

probability that the plan will be educationally successful, and

-another which will diminish that probability, there is no reason

for the Court to deliberately flaunt community opinion and make

jieven more abrasive the transition to desegregated schools. Parti

cipation in the process of choosing a pupil assignment plan for

!j . . . . . .the individual school districts is that option which improves the

measure of community acceptance and raises the probability of

<ii: success. Surely, in this time of crisis and tension over the

fi

'issues facea in this trial, it is no time to shut off individual

citizens and their immediately-elected local officials from

participation in the affairs of their schools.

Thus, the Detroit Board reiterates its strong belief

that the success of any plan of desegregation, both as a matter

of objectively creating the best possible plan with the best

available data, and as a matter of the best possible climate

j _ _

I for implementation is dependent upon the intensive involvement

| of local school districts. In doing so, the Detroit Board

jrecognizes that this may not be the easiest or most easilyj

j managed way of creating a pupil assignment plan. It is, however,

|the only way to create the best possible plan. As the testimonyI

| suggests, if there is to be metropolitan school desegregation,

it must be done right (Rankin, Metro Tr.467). With the

educational opportunities of nearly a million youngsters hanging

in the balance,it is unthinkable to disagree.

CONCLUSION

The goal of the Defendant Detroit Board of Education

in proposing a plan and advocating it can be succinctly stated:

18-

If we are going to do it, let's do it right." It is with that

purpose in mind that we submit the findings of fact, conclusions

of law, and proposed order which will follow.

!

i

i

i

M - |1

j'

-

>

Respectfully submitted,

RILEY AND ROUMELL

And:

Louis D. Beer

Attorneys for Defendant Detroit

Board of Education

720 Ford Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

Telephone: 962-8255

Date: May 5, 1972.

.(>

i

-19-

I

I

R I C A I O N

jt _ - certify that a copy of the foregoing Briefi|Of Defendant Detroit Board of Education and Other Defendants in

jjSupport of Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law and

,,tne Board s Metropolitan Detroit Plan has been served upon counsel

jOf record by United States Mail, postage pre-paid, addressed as follows:

S| LOUIS R. LUCAS

j WILLIAM E. CALDWELL

| 525 Commerce Title Building

I Memphis, Tennessee 38103

jl , . _ ....|j NATHANIEL R. JONES

ij General Counsel, NAACP

jj 1750 Broadway

ji New York, New York 100191 I

jj E. WINTHER MC CROOM

jj 324 5 Woodburn Avenue

:l Cincinnati, Ohio 45207

ji

ij JACK GREENBERG

jj NORMAN J. CHACUXIN

jj 10 Columbus Circle

jj New York, New York 10 019

DOUGLAS K. WEST

ROBERT B. WEBSTER

3700 Penobscot Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

WILLIAM M. SAXTON

1881 First National Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

EUGENE KRASICKY

Assistant Attorney General

Seven Story Office Building

525 West Ottawa Street

Lansing, Michigan 48913

THEODORE SACHS

1000 Farmer

Detroit, Michigan 48226

jj J. HAROLD FLANNERY

jj PAUL R. DIMOND

jj ROBERT PRESSMAN

j; Center for Law & Education

ji Harvard University

j: Cambridge, Massachusetts

ji 02138j

ROBERT J. LORD

8388 Dixie Highway

j Fair Haven, Michigan 48023

!

ij Of Counsel:

I! 'jj PAUL R. VELLA :

jj EUGENE R. 30LAN0WSKI

jj 30009 Schoenherr Road

jj Warren, Michigan 48093

ALEXANDER B. RITCHIE

2555 Guardian Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

BRUCE A. MILLER

LUCILLE WATTS

2460 First National Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

RICHARD P. CONDIT

Long Lake Building

860 West Long Lake Road

Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

48013

KENNETH 3. MC CONNELL

74 West Long Lake Road

Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

48013

i

i

Date: May 1972,

Respectfully submitted,

RILEY AND*ROUMELL

By: -RLouis D . Beer

720 Ford Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

Telephone: 962-8255 ” *

it

i

i

I