Board of Supervisors of Louisiana State University & Agricultural & Mechanical College v Ludley Supplemental Brief on Behalf of Appellants

Public Court Documents

December 31, 1957

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Board of Supervisors of Louisiana State University & Agricultural & Mechanical College v Ludley Supplemental Brief on Behalf of Appellants, 1957. c94349da-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c29d2552-9d31-4882-af6b-5deffaa0f271/board-of-supervisors-of-louisiana-state-university-agricultural-mechanical-college-v-ludley-supplemental-brief-on-behalf-of-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

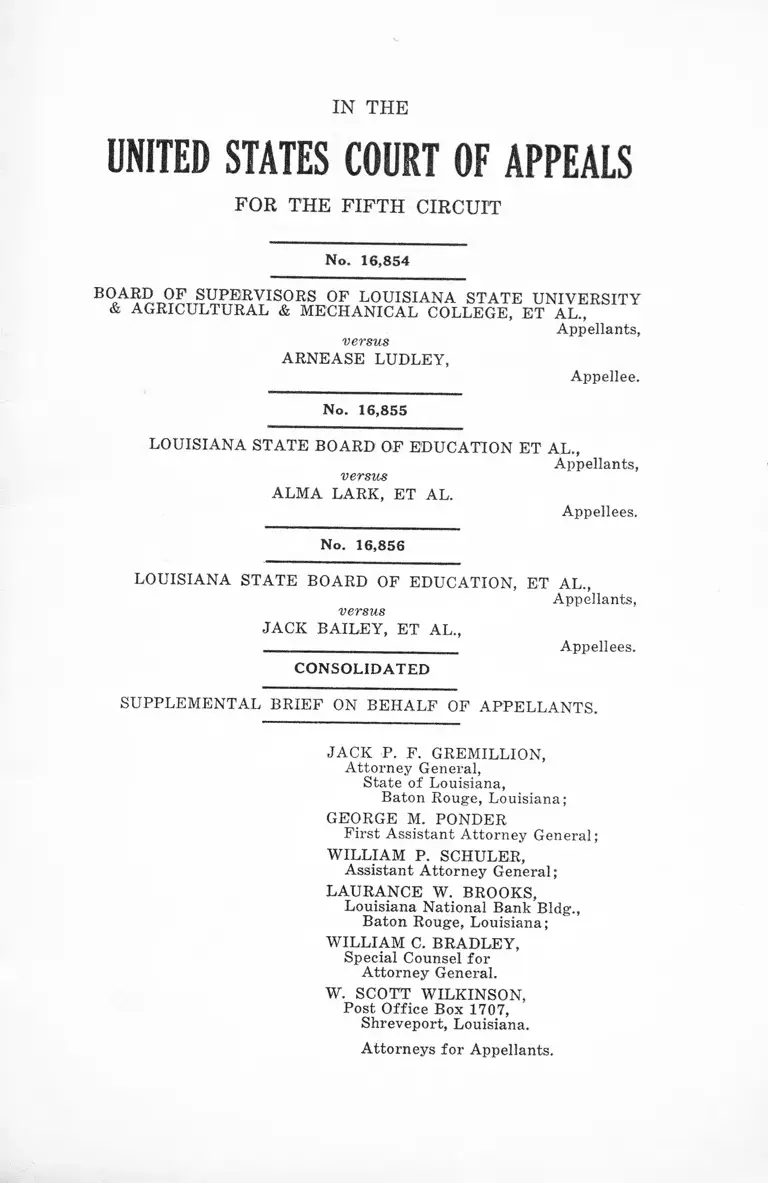

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 16,854

LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY

& AGRICULTURAL & MECHANICAL COLLEGE, ET AL.,

Appellants,

versus

ARNEASE LUDLEY,

Appellee.

No. 16,855

LOUISIANA STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION ET AL.,

Appellants,

versus

ALMA LARK, ET AL.

Appellees.

No. 16,856

LOUISIANA STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION, ET AL.,

Appellants,versus

JACK BAILEY, ET AL.,

_______ ______ __________ Appellees.

CONSOLIDATED

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF ON BEHALF OF APPELLANTS.

JACK P. F. GREMILLION,

Attorney General,

State of Louisiana,

Baton Rouge, Louisiana;

GEORGE M. PONDER

First Assistant Attorney General;

WILLIAM P. SCHULER,

Assistant Attorney General ;

LAURANCE W. BROOKS,

Louisiana National Bank Bldg.,

Baton Rouge, Louisiana;

WILLIAM C. BRADLEY,

Special Counsel for

Attorney General.

W. SCOTT WILKINSON,

Post Office Box 1707,

Shreveport, Louisiana.

Attorneys for Appellants.

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 16,854

BOARD OF SUPERVISORS OF LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY

& AGRICULTURAL & MECHANICAL COLLEGE, ET AL.,

Appellants,

versus

ARNEASE LUDLEY,

.________________ _ Appellee.

No. 16,855

LOUISIANA STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION ET AL-,

Appellants,

versus

ALMA LARK, ET AL„

No. 16,856

Appellees.

LOUISIANA STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION, ET AL.,

Appellants,

versus

JACK BAILEY, ET AL.,

Appellees.

CONSOLIDATED

MOTION FOR LEAVE OF COURT TO FILE SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF

NOW comes JACK P. F. GREMILLION, Attorney Gen

eral of the State of Louisiana, on behalf of the State of

Louisiana, and with respect represents:

1.

That the decision of the Lower Court was erroneous in

that the Court did not properly apply the Federal law, as

well as the law of the State of Louisiana.

a

That the State of Louisiana asks leave of this Honorable

Court to file a supplemental brief in support of its original

brief, for the reason that the issues involved herein are of

grave concern to the State; and that a copy of this brief

has been transmitted to the Clerk of this Court for filing

in the event this motion is allowed;

WHEREFORE, premises considered, appearer prays

that this Honorable Court grant petition leave to file a sup

plemental brief in this proceeding and that an order be duly

entered to this effect.

Further prays for all orders and decrees necessary and

for full, general and equitable relief.

Respectfully submitted,

JACK P. F. GREMILLION

Attorney General

State of Louisiana

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

GEORGE M. PONDER

First Assistant

Attorney General

WILLIAM P. SCHULER

Assistant Attorney General

LAURANCE W. BROOKS

Louisiana National Bank

Building

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

WILLIAM C. BRADLEY

Special Counsel for

Attorney General

W. SCOTT WILKINSON

Post Office Box 1707

Shreveport, Louisiana

Attorneys for Appellants

Ill

C E R T I F I C A T E

I hereby certify that a copy of the foregoing Motion has

been mailed all counsel of record in this case on this the-------

day of____________, 1957.

of Counsel

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 16,854

BOARD OF SUPERVISORS OF LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY

& AGRICULTURAL & MECHANICAL COLLEGE, ET AL„

Appellants,

versus

ARNEASE LUDLEY,

Appellee.

No. 16,855

LOUISIANA STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION ET AL.,

Appellants,

versus

ALMA LARK, ET AL.,

Appellees.

No. 16,856

LOUISIANA STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION, ET AL.,

Appellants,

versus

JACK BAILEY, ET AL.,

Appellees.

CONSOLIDATED

O R D E R

Considering the foregoing petition of Jack P. F. Gremil-

lion, Attorney General of the State of Louisiana, for leave

of Court to file a supplemental brief in this proceeding:

IT IS HEREBY ORDERED that Jack P. F. Gremillion,

Attorney General of the State of Louisiana, be and he is

hereby granted leave of Court to file a supplemental brief

in this proceeding.

THUS DONE AND SIGNED at New Orleans, Louisiana,

on this the____ day of------------------ , 1957.

J U D G E

United States Court of Appeals

Fifth Circuit

SUBJECT INDEX.

ARGUMENT:

That acts 15 and 249 of 1956 are constitutional both

on their face and in application................................ 1

That the Court attempted to use rules of statutory

construction where said rules were not ap

plicable ............................................................ 11

CONCLUSION................. ......................................................... 20

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE................................................. 22

AUTHORITIES CITED.

Aldredge v. Williams, 44 U. S. 9, 11 L. Ed. 469............. 14,16

Anniston Mgf Co. v. Davis, 301 U. S. 337, 81 L. Ed. 1443. 18

Ark. Nat. Gas Co. v. Ark R.R. Comm., 261 U. S. 379,

67 L. Ed. 705 ...... ..................... ..................................18, 19

Bush v. New Orleans Parish School Board, 242 F. 2d 156.. 11

Campbell v. Aldridge, 79 Pac 2d 257, 159 Or. 208, appeal

dismissed 305 U. S. 559, 83 L. Ed. 352.......................... 7

Carey v. S.D., 250 U. S. 118, 63 L. Ed. 886.......................... 18

Chippwa Indians v. U. S., 301 U. S. 358, 81 L. Ed. 1156.. 18

Cumberland T & T Co. v. La. Pub. Service Comm., 260

U. S. 216, 67 L. Ed. 223,-...--...........-.................. 20

District of Columbia v. Gladding, 263 Fed. 628.................. 11

Duplex Printing Press Co. v. Deering, 254 U. S. 474, 65

L. Ed. 360........... ...........................................................13,15

Ex parte Collett, 337 U. S. 55, 93 L. Ed. 1207............... ...... 14,

Fairport P & ER. Co. v. Meredith, 292 U. S. 589, 78 L. Ed.

1446 ............................................ ....................................... 14,

Foley v. Benedict, 55 S.W. 2d 805, 86 ALR 477.................. 7

AUTHORITIES CITIED— (Continued)

Hopkins Fed S & L Assn v. Cleary 296 U. S. 315, 80 L. Ed.

251 ................................................................................. ...... 18

In re Walling, 324 U. S. 244, 89 L. Ed. 921.............. ........... 14

Kuchner v. Irving Trust Co., 299 U. S. 445, 81 L. Ed. 340 . 14

Lapina v. Williams, 232 U. S. 90, 58 L. Ed. 519........ 15

Manchester v. Leiby, 117 F 2d 661, 665 Cert Den. U. S.

562, 85 L. Ed. 1522........................................... ............... 19

Maxwell v. Dow, 176 U. S. 601-2, 44 L. Ed. 605..... ............ 14

Mayo v. Lakeland Co., 309 U. S. 318-19, 84 L. Ed. 780..... 19

Mo. Pac. Ry Co. v. Boone, 276 U. S. 466, 70 L. Ed. 688..... 18

N.L.R.B. v. Jones & Laughlin, 301 U. S. 1, 81 L. Ed.

893 ____ ________ _____ ______ __________ _______ ______ 18

No. Pac. Ry. Co. v. U. S., 156 F. 2d, 346, affirmed 330

U. S. 248, 91 L. Ed. 876...... ........................................... 11

R.R. Comm. v. C B & Q. R. Co., 257 U. S. 589, 66 L. Ed.

383 _________________ __ ________ ____________ _______ 13

South Utah Mines v. Beaver County, 262 U. S. 331, 67 L.

Ed. 1008............................ .................... .............................. 18

Texas v. E. Tex. R. Co., 258 U. S. 204, 66 L. Ed. 566..... 18

Trustees of the University of Mississippi v. Waugh, 105

Miss. 623, 62 So. 827, ALR 1915D 588__________ __ _ 5

U. S. v. Colo, and N. W. Ry. Co. 157 Fed. 321, 330........... 11

U. S. v. Kung Chen Fur Corp., 188 F 2d 577...................... 14

U. S. v. Rice, 327 U. S. 753, 90 L. Ed. 989............................. 12

Walling v. McKay, 70 Fed. Sup. 160 affirmed 164 F. 2d

40 - ........... ................. .............................. ......................... i i

Waugh v. Mississippi University, 237 U. S. 589, 59 L. Ed.

1131....................................................................................... 5

LOUISIANA STATUTES:

Act 249 of 1956 (La. R.S. 17:443)... ...................................... 3

Act 15 of 1956 (La. R.S. 17:2131-2135).............................. 2

Act 555 of 1954........ ....................................... ........................ . 11

MISCELLANEOUS:

American Jurisprudence, Vol. 55, p. 10............................... . 5

Corpus Juris Secundum;

Vol 14, p. 1359................................................................... 7

Vol 16, pp. 375-382.................. 18

Vol. 16, pp. 383-4. 17

Vol 16, pp. 383-4. 17

Vol 16, pp. 387-8........... 18

Vol 78, pp. 624, 626, 630.................................................. 7, 8

Corpus Juris Secundum;

Vol 78, p. 631........... .................. ......................... ..............8, 9

Vol 82, p. 527..... ................... ............................. ............. . 12

Vol 82, pp. 544-5......... ........................................................ . 16

Vol 82, pp. 813-814............................................................ 10

Vll

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 16,854

BOARD OF SUPERVISORS OF LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY

& AGRICULTURAL & MECHANICAL COLLEGE, ET AL.,

Appellants,

ARNEASE LUDLEY,

Appellee.

No. 16,853

LOUISIANA STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION ET AL.,

Appellants,

versus

ALMA LARK, ET AL.,

Appellees.

No. 16,856

LOUISIANA STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION, ET AL.,

Appellants,

versus

JACK BAILEY, ET AL.,

Appellees.

CONSOLIDATED

May it please the Court:

That Acts 15 and 249 of 1956 are constitutional

both on their face and in application.

In 1956 the Legislature of Louisiana enacted Act No.

15 of 1956 (La. R.S. 17:2131 - 2135) and Act 249 of 1956

(La. R.S. 17:443). These statutes are attacked by the plain

tiffs and appellees as being in violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment of the United States Constitution on the ground

that they deny the plaintiffs and others similarly situated

of rights, privileges and immunities secured by the Consti

tution and laws of the United States. Plaintiffs are negroes

who have sought admission to the Louisiana State University,

and to other institutions of higher learning maintained by

2

the State of Louisiana. They were refused admission because

they failed to present the Certificate of Eligibility required

by Act 15 of 1956 (R.S. 17:2131 - 2185).

Act 15 of 1956 hereafter referred to as Act 15, or as

the Eligibility Statute, provides in Section 1:

“ § 2131. Certificate; requirement; contents

No person shall be registered at or admitted to any

publicly financed institution of higher learning of this

state unless he or she shall have first filed with said

institution a certificate addressed to the particular in

stitution sought to be entered attesting to his or her

eligibility and good moral character. This certificate

must be signed by the superintendent of education of

the parish, county, or municipality wherein said appli

cant graduated from high school, and by the principal

of the high school from which he graduated. Act 1956,

No. 15, § 1.”

The remaining sections of this statute merely provide

for the form of the certificate, notice of the requirements

of the law, penal provisions for its violation, and permits

the State Board of Education and the Board of Supervisors

of Louisiana State University to adopt other entrance re

quirements including aptitude tests and medical examina

tions. The Act makes no mention of race or color, and in

its terms applies to all students who seek admission to all

institutions of higher learning maintained by the State of

Louisiana. There is nothing ambiguous about the statute, its

meaning is quite clear, and there is nothing in the Act which

would discriminate against any qualified students seeking

admission to these institutions.

3

The other Act of the Legislature attacked by the plain

tiffs in these consolidated cases, namely; Act 249 of 1956

(La. R.S. 17:443) relates to the grounds on which a perma

nent teacher in the public schools of the state may be re

moved from office. This Act provides in part:

“ A permanent teacher shall not be removed from

office except upon written and signed charges of wilful

neglect of duty, or incompetency or dishonesty, or of

being a member of or of contributing to any group,

organization, movement or corporation that is by law or

injunction prohibited from operating in the State of

Louisiana, or of advocating or in any manner perform

ing any act toward bringing about integration of the

races within the public school system or any public in

stitution of higher learning of the State of Louisiana,

and then only if found guilty after a hearing by the

school board of the parish or city, as the case may be,

which hearing may be private or public, at the option

of the teacher . . .”

The remaining provisions of this Act provide for the

procedure to be taken including the service of written

charges on the teacher in advance of the hearing and afford

ing him the right to counsel. Provision is made for a right

of appeal in the event of an adverse decision to a court of

competent jurisdiction. The Act also provides that if the

finding of the school board is reversed by the Court, the

teacher shall be entitled to full pay for any loss of time or

salary.

The plaintiffs in these cases do not allege that they are

teachers or that the provisions of this Act have in any way

been applied to them. The validity of the Act has been ques

tioned on the tenuous ground that this Act would prevent

plaintiffs from securing the Certificate of Eligibility pro

4

vided for in Act 15. It may here be noted that Act 249

applies to teachers in the public schools and has no applica

tion whatever to school superintendents or school principals

who are the officers designated in the Eligibility Statute as

the persons who are to furnish such certificates. School

superintendents and school principals are not forbidden to

issue such certificates nor are they required to discriminate

against any person on account of race in the issuance thereof.

No penalty would be incurred by such officials if they were

to issue to a negro a Certificate of Eligibility to attend any

college of his choice in this State. The plaintiffs are there

fore unaffected by any of the provisions contained in the

teachers removal statute. The latter statute is utterly unre

lated to the Eligibility Statute.

It may here be noted that Section 2 of Act 249 of 1956

provides that in case any part of the Act shall be held to be

unconstitutional, this shall not have the effect of invalidat

ing any part of it that is constitutional. If therefore the

Court should invalidate the clause in this Act which permits

the school board to discharge a teacher who advocates inte

gration of the races within the public school system, this

would cut away the only connection that judicial imagina

tion could supply between Act 15 and Act 249. Nevertheless,

as pointed out hereinabove the teacher removal statute applies

only to Superintendents and principals and has nothing to

do with the present case.

In determining the rights of these plaintiffs to demand

admission to any institution of higher learning in Louisiana

they must be considered as ordinary citizens of this State

who possess no greater right than other citizens by virtue

of their color. No Court has yet decided that negroes have

any greater rights to attend the public schools or the colleges

and universities of the State than members of any other

5

race. Their rights are determined by the general principles

of law and of right which apply to all who seek admission

to these schools.

To begin with no one has a natural right to attend any

educational institution maintained by the State, as stated in

55 American Jurisprudence 10:

§ 14. State Universities.— The right to attend the

educational institutions of a state is not a natural one,

but is a benefaction of the law. One seeking to become

a beneficiary of this gift must submit to such conditions

as the law imposes as a condition precedent thereto.

Hence, where a legislature, acting under a constitutional

mandate, establishes a university, it may also legislate

as to what persons are entitled to be admitted to its

privileges and to instruction therein . . .”

The foregoing statement is taken almost verbatum from

the text of the decision of the Supreme Court of Mississippi

in the case of Trustees of the University of Mississippi v.

Waugh, 105 Miss. 623, 62 So. 827, ALR 1915D 588 which

decision was affirmed by the Supreme Court of the United

States in Waugh v. Mississippi University, 237 U. S. 589, 59

L. Ed. 1131. The Supreme Court affirmed the following rul

ing of the Supreme Court:

“ . . . The right to attend the educational institu

tions of the state is not a natural right. It is a gift of

civilization, a benefaction of the law. If a person seeks

to become a beneficiary of this gift, he must submit to

such conditions as the law imposes as a condition pre

cedent to this right . . .

We can see nothing in the act which is violative

of any section of the Constitution. Whether the act was

6

a wise one or an unwise one, was a question for the

legislature to determine . .

The Legislature of Louisiana undoubtedly has the right

to prescribe the conditions under which students may be

admitted to the colleges and universities of the State. In

affirming the decision of the State Court the Supreme Court

of the United States said: (237 U. S. 595-6, 59 L. Ed. 1136-7)

“ The next contention of complainant has various

elements. It assails the statute as an obstruction to his

pursuit of happiness, a deprivation of his property and

property rights, and of the privileges and immunities

guaranteed by the Constitution of the United States.

Counsel have considered these elements separately and

built upon them elaborate and somewhat fervid argu

ments, but, after all, they depend upon one proposition;

whether the right to attend the University of Missis-

is an absolute or conditional right. It may be put more

narrowly,— whether, under the Constitution and laws

Mississippi, the public educational institutions of the

state are so far under the control of the legislature that

it may impose what the supreme court of the state calls

‘disciplinary regulations.’

To this proposition we are confined, and we are not

concerned in its consideration with what the laws of

other states permit or prohibit. Its solution might be

rested upon the decision of the supreme court of the

state. That court said: ‘The legislature is in control of

the colleges and universities of the state, and has a right

to legislate for their welfare, and to enact measures for

their discipline, and to impose the duty upon the trus

tees of each of these institutions to see that the require

ments of the legislature are enforced; and when the

legislature has done this, it is not subject to any control

7

by the courts.’ (105 Miss. 635, L.R.A. 1915D, 588, 62

So. 827.)

This being- the power of the legislature under the

Constitution and laws of the state over its institutions

maintained by public funds, what is urged against its

exercise to which the Constitution of the United States

gives its sanction and supports by its prohibition? . . .”

In the original brief herein filed authority is quoted to

the effect that the Legislature may regulate the conditions

on which students may be admitted to a University main

tained by the State.

14 C.J.S. 1359

Foley v. Benedict, 55 S. W. 2d 805, 86 ALR 477

Waugh v. Miss., supra

Furthermore, the State has the right to control and pre

scribe the limits to which it will go in supplying education

at public expense as stated in 78 C.J.S. 624:

“ The power to establish and maintain systems of

common schools, to raise money for that purpose by

taxation, and to govern, control, and regulate such schools

when established is one of the powers not delegated to

the United States by the federal Constitution, or pro

hibited by it to the states, but is reserved to the states;

respectively or to the people, and the people through the

legislature and the constitution have the right to con

trol and prescribe the limits to which they will go in

supplying education at public expense . . .”

Public education and the control thereof are proper sub

jects for the exercise of the State’s police power.

78 C.J.S. 626

Campbell v. Aldridge, 79 Pac. 2d 257, 159 Or. 208,

appeal dismissed 305 U. S. 559, 83 L. Ed. 352.

8

The following statement in 78 C.J.S. 627 is supported by

numerous citations of authority:

“ The state in legislating concerning education is

exercising its broad sovereign power, and, subject, only

to any requirements or restrictions prescribed by the

constitution, the legislature has a large discretion as to

the manner of accomplishing its purpose . .

In this connection, the following statement in 78 C.J.S.

630 is pertinent:

“ Regulation of education and of the school system

is a governmental function, and generally the police

power extends to such regulation. The management and

administration of the public schools and of the school

system, like their establishment and maintenance, are

primarily affairs of the state, and the legislature has

full authority, subject to constitutional restrictions, to

enact such laws as it may deem necessary and expedient

for the proper administration and regulation of the pub

lic schools and the promotion of their efficiency . . .”

In view of the above the Courts have uniformly held

that the exercise of powers by the school authorities will

be interfered with by the Courts only in the case of a clear

abuse of authority and that the burden of showing such an

abuse is a heavy one. The authorities on this subject are

sumed up in 78 C.J.S. 631, as follows:

“ . . . While the courts have power in a proper pro

ceeding to determine what the powers of school authori

ties are, and whether or not the authorities have ex

ceeded them, the exercise of discretion by school authori

ties will be interfered with only when there is a clear

abuse of discretion or a violation of law, and the burden

9

of showing such an abuse is a heavy one. In other words,

the courts are not concerned with the wisdom of the

policy of school authorities, and they are without power

to interfere with the policies of such authorities as long

as they act in good faith within their statutory powers.”

In their original brief the appellants point out that no

where in the complaint does the plaintiff avow that the acts

of the Legislature attacked in this case have been adminis

tered unfairly or in a discriminatory manner. On the other

hand, the affidavits of various college officials appearing on

pages 32-38 of the transcript in this case show affirmatively

that the Eligibility Certificate law has been uniformly applied

to all applicants for admission to the colleges involved in

this proceeding, and without regard to race or color.

All that the eligibility statute requires is a certificate

that the applicant is qualified for admission to an institu

tion of higher learning which he seeks to enter and that he

is of good moral character. Surely the State cannot be ex

pected to furnish higher education to unqualified students,

and in the exercise of its police power it can certainly deny

admission to applicants who are morally unfit to attend a

college or university. Attendance as a student in our colleges

and universities is a privilege given by the State which must

be zealously guarded. The students in such institutions are

intimately associated with one another in the classrooms,

dormitories and in social contacts. To say that a State may

not require of an applicant a certificate as to his moral

character, regardless of his race, is to assert that in the

realm of education the State has no authority to promote

morality of its young people. This power of the State finds

it most important exercise in all matters that relate to the

morality and well-being of its youth. The Judgment of the

District Court would deny the State of Louisiana this right

solely on the supposition that the eligibility statute might

10

be used as a means of discrimination against negroes in this

State.

The plaintiffs have contended and the lower Court has

apparently ruled that although the Eligibility Statute is not

of itself objectionable on its face it is nevertheless uncon

stitutional because it is a part of a statutory system to

discriminate against negroes. However, as pointed out in the

original brief this Act is complete within itself and depends

upon no implementation from any other acts of the Legis

lature which were in effect at the time it was passed or

which was passed at the same session of the Legislature.

Since this is true, the Act must be considered alone and on

its own merits. There is no ambiguity in its terms and there

is nothing uncertain or obscure about its verbage. There is

therefore no need for interpretation on the part of the Court.

As pointed out on page 21 of appellant’s brief, the Supreme

Court of the United States has in numerous decisions held

that none of the rules of statutory construction may be

used to ascertain the meaning or application of a statute

where there is no ambiguity or doubt as to the meaning of

the words employed by the Legislature. The Court therefore

has no right to refer to other statutes in pari materia, or to

import the provisions of such statutes into an act whose

meaning is not doubtful. The general rule on the subject is

thus stated in 82 C.J.S. 813-814:

“ • • • It must not be overlooked that the rule re

quiring statutes in pari materia to be construed to

gether is only a rule of construction to be applied as an

aid in determining the meaning of a doubtful statute,

and that it cannot be invoked where the language of a

statute is clear and unambiguous. So, the rule of in pari

materia does not permit the use of a previous statute to

control by way of former policy the plain language of

subsequent statutes, or to add a restriction thereto found

11

in the earlier statute and excluded from the later statute;

nor has the rule any application in construing an act

intended to be complete in itself. In other words, the rule

of construction may not be applied to narrow the com

pass of one statute by reference to another nonconflict

ing and nonrepealing act, and restrictions placed on a

power in one instance cannot be extended to another

case for which they were not intended and for which

another provision is made.”

The foregoing text is supported by numerous decisions

of State and Federal Courts including No. Pac. Ry. Co. v. TJ.

S., 156 F. 2d. 346, affirmed 330 U. S. 248, 91 L. Ed. 876, Wall

ing v. McKay, 70 Fed. Sup. 160 affirmed 164 F. 2d 40, District

of Columbia, v. Gladding, 263 Fed. 628, U.S. v. Colo, and

NW Ry. Co., 157 Fed. 321, 330.

As a matter of fact there are no statutes in pari materia

which in any way relate to the subject matter of the statutes

in question. Certainly there are none on the subject of segre

gation. The Federal Courts have written o ff all of Louisiana’s

legislation pertaining to segregation in public schools and

colleges. The provisions of the Constitution of Louisiana re

quiring segregation have been held invalid by this Court

and the Acts of the Legislature, particularly Act 555 of 1954,

which require separate schools for the races have been nulli

fied. (Bush v. New Orleans Parish School Board, 242 F. 2d

156) If these acts are dead letter material they can hardly

be revived as implements of interpretation for a statute such

as the Eligibility Statute which nowhere refers to segregation

or racial differences.

That the Court attempted to use rules of statutory

construction where said rules were not applicable

Although the Eligibility Act clearly and distinctly evi

12

dences a lawful purpose that lies within the police power of

the State, and there is nothing arbitrary, unreasonable, or

discriminatory either in its expressed object or in the means

to be employed to achieve such object, the District Judge

imported into the Act a legislative intent which he discovered

in some press reports regarding the Act. These press reports

reflected ideas gained by some newspaepr reporter who inter

viewed the Chairman of the Joint Legislative Committee

which is not the committee that acted on the bill in the

Legislature. From statements made by this individual mem

ber of the Legislature the Court below found only a nefarious

purpose in the Act and disregarded the moral aspects of the

law. To say that the Legislature had no regard for the health

and morals of its young people and that it acted only to

discriminate against a minority race is to arbitrarily malign

a coordinate branch of the government and to judicially usurp

its legislative functions. The District Judge wrote into the

Act a legislative intent that is nowhere expressed in the

Act. He resorted to unreliable extraneous hearsay to create

doubt and suspicion as to the constitutionality of the law and

refused to attribute to the State of Louisiana any good pur

pose that such a law can and will undoubtedly serve. If the

Federal Courts intend to import doubt and to interpret with

suspicion by Acts of the State Legislature regulating public

schools, and if they propose to strike down all laws on the

subject that carry any possibility of wrongful execution, the

State will be deprived of sovereignty in a field where it, and

method of interpreting a clear and unambiguous statute

is contrary to every principle of Judicial power.

Rules of Construction are useful only in cases of doubt.

They should never be used to create it, but only to remove it.

(82 CJS 527 and cases cited)

In the case of U. S. v. Rice, 327 U. S. 753, 90 L. Ed. 989

the Supreme Court said:

13

. . Statutory language and objective, thus ap

pearing with resonable clarity, are not to be overcome

by resort to a mechanical rule of construction, whose

function is not to create doubts, but to resolve them

when the real issue or statutory purpose is otherwise

obscure. United States v. California, supra (297 U. S. 186,

80 L. Ed. 573, 56 S. Ct. 421.)”

The rule just stated has been applied by the Supreme

Court to prohibit the use of Committee Reports and explana

tory statements made by members of Congress regarding the

purpose of a law which is not therein expressed. So in R.R.

Comm. v. C B & Q.R. Co., 257 U. S. 589, 66 L. Ed. 383 the

court ruled:

“ . . . Committee reports and explanatory state

ments of members in charge, made in presenting a bill

for passage, have been held to be a legitimate aid to the

interpretation of a statute where its language is doubtful

or obscure. Duplex Printing Press Co. v. Deering, 254

U. S. 443, 475, 65 L. Ed. 354, 16 A. L. R. 196, 41 Sup.

Ct. Rep. 172. But when, taking the act as a whole the

effect of the language used is clear to the court, ex

traneous aid like this cannot control the interpretation,

Pennsylvania R. C. v. International Coal Min. Co. 230 U.

S. 184, 57 L. Ed. 1446, 1451, 33 Sup. Ct. Rep. 893, Ann.

Cas 1915A, 315; Caminetti v. United States, 242 U. S.

470, 490, 61 L. Ed. 442, 445, L.R.A. 1917B, 1168. Such

aids are only admissible to solve doubt, and not to

create it. . . .”

The District Judge under the pretense of conturing a

clear and unambiguous Act of the Legislature resorted to

extraneous hearsay statements to nullify a state law that

14

clearly evinces a lawful object. He committed a grievous error

in so doing.

See also:

U. S. v. Rung Chen Fur Corp., 188 F 2d 577,

Aldredge v. Williams, 44 U. S. 9,11 L. Ed. 469

Ex parte Collett, 337 U. S. 55, 93 L. Ed. 1207

In re Walling 324 U. S. 244, 89 L. Ed. 921

Kuchner v. Irving Trust Co., 299 U. S. 445, 81 L. Ed. 1446

Fairport P. & ER. Co. v. Meredith, 292 US 589, 78 L. Ed.

1446

Even when it may be necessary to interpret a doubtful

statute the courts attach little or no importance to the state

ments of individual legislators as to the purpose of the law.

We quote from Maxwell v. Dotu, 176 U. S. 601-2, 44 L. Ed. 605:

“Counsel for plaintiff in error has cited from the

speech of one of the Senators of the United States,

made in the Senate when the proposed Fourteenth

Amendment was under consideration by that body,

wherein he stated that among the privileges and im

munities which the committee having the amendment in

charge sought to protect against invasion or abridgment

by the states were included those set forth in the first

eight amendments to the Constitution; and counsel has

argued that this court should therefore give that con

struction to the amendment which was contended for by

the Senator in his speech.

. . . It is clear that what is said in Congress upon

such an occasion may or may not express the views of

the majority of those who favor the adoption of the

measure which may be before that body, and the ques

tion whether the proposed amendment itself expresses

the meaning which those who spoke in its favor may

15

have assumed that it did, is one to be determined by the

language actually therein used, and not by the speeches

made regarding it.

What individual Senators or Representatives may

have argued in debate, in regard to the meaning to be

given to a proposed constitutional amendment, or bill, or

resolution, does not furnish a firm ground for its proper

construction, nor is it important, as explanatory of the

grounds upon which the members voted in adopting it.

United States v. Trans-Missouri Freight Asso. 166 U. S.

290, 318, 41 L. Ed. 1007, 1019, 17 Sup. Ct. Rep. 540; Dun

lap v. United States, 173 U, S. 65, 75, 43 L. Ed. 616, 19

Sup. Ct. Rep. 319.”

Again in Lapina v. Williams, 232 U. S. 90, 58 L. Ed. 519,

the Court said:

“ Counsel for petitioner cites the debates in Congress

as indicating that the act was not understood to refer

to any others than immigrants. But the unreliability of

such debates as a source from which to discover the

meaning of the language employed in an act of Congress

has been frequently pointed out ( United States v. Traris-

Missouri Freight Asso. 166 U. S. 290, 318, 41 L. Ed. 1007,

1019, 17 Sup. Ct. Rep. 540, and cases cited), and we are

not disposed to go beyond the reports of the committees.

Church of the Holy Trinity v. United States, 143 U. S.

457, 463, 36 L. Ed. 226, 229, 12 Sup. Ct. Rep. 511; Binus

v. United States, 194 U. S. 486, 495, 48 L. Ed. 1087, 1090,

24 Sup. Ct. Rep. 816; Johnson v. Southern P. Co. 196

U. S. 1, 19, 49 L. Ed. 363, 370, 25 Sup. Ct. Rep. 158, 17

Am. Neg. Rep. 412).”

We quote the following from Duplex Printing Press Co.

v. Peering, 254 U. S. 474, 65 L. Ed. 360:

“By repeated decisions of this court it has come to

16

be well established that the debates in Congress expres

sive of the views and motives of individual members are

not a safe guide, and hence may not be resorted to, in

ascertaining the meaning and purpose of the lawmaking

body. Aldredge v. Williams, 3 How. 9, 24, 11 L. Ed. 469,

475; United States v. Union P. R. Co. 91 U. S. 72, 79, 23

L. Ed. 224, 228; United States v. Trans-Missouri Freight

Asso., 166 U. S. 290, 318, 41 L. Ed. 1007, 1019, 17 Sup Ct.

Rep. 540. But reports of committees of House or Senate

stand upon a more solid footing, and may be regarded as

an exposition of the legislative intent in a case where

otherwise the meaning of a statute is obscure. Binns v.

United States, 194 U. S. 486, 495, 48 L. Ed. 1087, 1090, 24

Sup. Ct. Rep. 816. . . .” (Emphasis supplied)

It is not to be presumed that the Legislature intended to

exceed its powers or that it sought to achieve an unlawful

objective. To the contrary every presumption must be in

dulged that it intended to enact a valid statute for a bene

ficial purpose. The courts all agree with the following state

ment made in 82 C.J.S. 544-5:

“ It is presumed that the legislature acted from hon

orable motives, in accordance with reason and common

sense, and with a full knowledge of the constitutional

scope of its powers, and that it did not intend to ex

ceed its powers, or to give its enactments an extra

territorial operation. It is also presumed that it intended

to enact a valid, effective, and permanent statute which

would have a beneficial effect, favoring the public inter

est, and which would achieve the purpose for which the

statute was adopted; and there is a presumption against

a construction which would render a statute ineffective

or inefficient, or which would cause grave public injury

or even inconvenience. . . .”

The words and phrases of the Eligibility Act manifest

17

clearly a lawful purpose. The statements imputed to one of

the Legislators who passed the Act indicate a purpose which

the District Judge concluded to be unlawful. Even if the Act in

and of itself was susceptible to either interpretation the Lower

Court should have adpoted the construction which would

have upheld the validity of the law— as stated in 16 C.J.S.

“ If a statute is susceptible of two constructions, one

of which will render it constitutional and the other of

which will render it unconstitutional in whole or in part,

or raise grave and doubtful constitutional questions, the

court will adopt that construction of the statute which,

without doing violence to the fair meaning of language

employed by the legislature therein, will render it valid,

and give effect to all of its provisions, or which will free

it from doubt as to its constitutionality, even though the

other construction is equally reasonable, or seems the

more obvious, natural, and preferable, interpretation,

The above rule, followed in all jurisdictions, furthermore

adds, quoting 16 C.J.S. 383-4:

“As a consequence of the rule of construction favor

ing validity, the courts will not adopt a strained, doubtful,

restricted, narrow, rigid, strict, or literal interpretation

in order to condemn a statute or resolution as uncon

stitutional, nor may they change or add to, the wording

of the statute, or resort to implication, or innuendo, in

order to destroy it. Also, the courts will not sustain an

attack on a statute if it may be constitutionally upheld

on any reasonable or sound theory, or any reasonable

construction, or any reasonable or rational ground, or any

reasonable, rational, or legal basis, or if any rational

basis of fact can reasonably be conceived to sustain it . . . ”

These rules have been consistently followed by the

18

Supreme Court of the United States. See:

Note 6,16 C. J. S. 376 and cases cited

Chip-pica Indians v. U. S., 301 U. S. 358, 81 L. Ed. 1156

Anniston Mfg Co. v. Davis, 301 U. S. 337, 81 L. Ed. 1443

N.L.R.B. v. Jones & Laughlin, 301 U. S. 1, 81 L. Ed. 893

Hopkins Fed S & L Assn v. Cleary, 296 U. S. 315, 80 L.

Ed. 251

Mo. Pac. Ry Co. v. Boone, 276 U. S. 466, 70 L. Ed. 688

South Utah Co. v. Beaver, 262 U. S. 325, 67 L. Ed. 1004

Ark Nat. Gas Co. v. Ark R. R. Comm, 261 U. S. 379, 67 L.

Ed. 705

Texas v. E. Tex. R. Co., 258 U. S. 204, 66 L. Ed. 566

Carey v. S. D., 250 U. S. 118, 63 L. Ed. 886

There is another rule of law that would preclude the

federal courts from invalidating the Act of the Legislature

of Louisiana. That is the rule that federal courts should not

hold a State law unconstitutional unless such a conclusion

is unavoidable. See 16 C. J. S. 387-8 and cases cited.

In South Utah Mines v. Beaver County, 262 U. S. 331,

67 L, Ed. 1008 plaintiff argued that a State statute would

produce an unjust and discriminatory result, and should

therefore be held unconstitutional as a violation of the 14th

Amendment. The Court rejected this argument, saying:

“ These statutory provisions, so far as we are in

formed, have not received the consideration of the state

courts, and we will not assume, in advance of such consid

eration, that they will be so construed as to produce that

result. See Plymouth Coal Co. v. Pennsylvania, 232 U. S.

531, 58 L. Ed. 713, 720, 34 Sup. Ct. Rep. 359; Missouri

K. & T. R. Co. v. Cade, 233 U. S. 642, 650, 58 L. Ed. 1135,

1138, 34 Sup. Ct. Rep. 678. Clearly, they are sus

ceptible of a construction which will preclude their ap

19

plication to the case now under consideration and as that

construction will resolve all doubt in favor of their con

stitutionality, it is our duty to adopt it. Plymouth Coal Co.

v. Pennsylvania, Supra, p. 546; St. Louis Southwestern

R. Co. v. Arkansas, 235 U. S. 350, 369, 59 L. Ed. 265, 274,

35 Sup. Ct. Rep. 99; Arkansas Natural Gas Co. v. Arkan

sas R. Commission, 261 U. S. 379, ante, 705, 43 Sup. Ct.

Rep. 387, decided March 19, 1923.”

In any event, the federal courts should not invalidate a

state law on the suppostion that it will be given an uncon-

al application by the state courts or by State officials charged

with its enforcement, as stated in Manchester v. Leiby, 117

F 2d 661, 665, Cert. Den. 313 U. S. 562, 85 L. Ed. 1522:

“ If, conceivably, the ordinance might be given an

interpretation of broader sweep and more doubtful con

stitutionality, the notable and altogether proper reluct

ance of federal courts to issue injunctions against state

and city officials, restraining their enforcement of crim

inal laws and ordinances, would lead us to adopt the

most innocent interpretation until the state courts have

ruled otherwise, or at least until the local officials have

proceeded to act on an interpretation which brings the

law or ordinance in conflict with constitutional guaran

tees. . . .”

In this class of cases where an injunction is sought

challenging the constitutionality of state laws the Su

preme Court has insisted that there be a clear and persuasive

showing of unconstitutionality and of irreparable injury. So

in Mayo v. Lakeland Co., 309 U. S. 318-9, 84 L. Ed. 780,

the Court said:

“ The legislation requiring the convening of a court

of three judges in cases such as this was intended to

20

insure that the enforcement of a challenged statute

should not be suspended by injunction except upon a

clear and persuasive showing of unconstitutionality and

irreparable injury. Congress intended that, in this class

of suits, prompt hearing and decision shall be afforded

the parties so that the states shall be put to the least

possible inconvenience in the administration of their

laws. . .”

As Chief Justice Taft stated in Cumberland T & T Co.

v. La. Pub. Service Comm. 260 U. S. 216, 67 L. Ed. 223,

“ conflict between Federal and State authority (is) always

to be deprecated.”

CONCLUSION

From the foregoing discussion and the authorities cited,

the following principles are established:

1. The two Acts of the Legislature challenged by Plain

tiffs in this proceeding are in no way related to one another.

In fact, Act 249 of 1956 relating to the removal of teachers

has no application whatever to this case.

2. If the Court were to find that Act 249 of 1956 is

unconstitutional in its clause relating to integration of the

races in the public school system it would thereby remove

any objection that might be made to Act 15 of 1956, the

Eligibility Act, since this clause furnishes the only con

nection that the District Judge found to exist between the

two statutes.

3. Plaintiffs have no inherent right to attend any col

lege or university maintained by the State, and must sub

21

mit to such conditions as the Legislature may impose as a

condition precedent to their admission to such an institution.

4. The power to establish and maintain colleges and uni

versities is a broad sovereign power reserved by the states

and constitutes and exercise of the police power of the state.

5. The courts have no right to resort to rules of construc

tion in ascertaining the meaning or the application of a

statute where there is no ambiguity or doubt as to the mean

ing o f the words employed by the Legislature. The District

Judge therefore erred in importing into the Eligibility Act

the provisions of other State statutes on the subject of segre

gation, and also erred in determining the purpose of the

statute to be unlawful because of statements made by an

individual of the Legislature as to its purpose.

6. Statements of individual members of the Legislature

as to the meaning or purpose of a law are unreliable as a

source from which to discover their true meaning or pur

pose of such a law, and are entitled to consideration only

where the language of a statute is doubtful or obscure.

7. If a statute is susceptible to two constructions, one

of which will render it constitutional and the other of which

will render it unconstitutional in whole or in part, the court

will adopt that construction which will render it valid, and

will uphold it only on reasonable or legal basis which might

sustain it.

8. The Federal Courts should not hold a State law un

constitutional unless such a conclusion is unavoidable. Since

the Eligibility Act is clear and certain in its terms

and has a lawful object the District Judge erred in nulli

22

fying the statute on the basis of extraneous hearsay state

ments regarding its purpose.

Respectfully submitted,

JACK P. F. GREMILLION,

Attorney General,

State of Louisiana,

Baton Rouge, Louisiana;

GEORGE M. PONDER

First Assistant Attorney General;

WILLIAM P. SCHULER,

Assistant Attorney General;

LAURANCE W. BROOKS,

Louisiana National Bank Bldg.;

Baton Rouge, Louisiana,

WILLIAM C, BRADLEY,

Special Counsel for

Attorney General.

W. SCOTT WILKINSON,

Post Office Box 1707

Shreveport, Louisiana

Attorneys for Appellants.

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on this day I have served copies

of the forgoing supplemental brief on behalf of appellants on

counsel to appellees by placing the same in the United States

Mail with sufficient postage affixed thereto.

Dated this------ day of December, 1957.

GEORGE M. PONDER

Attorney for Appellant