Order Approving Coffee County's Settlement; Orders

Public Court Documents

October 23, 1986 - October 30, 1986

4 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Dillard v. Crenshaw County Hardbacks. Order Approving Coffee County's Settlement; Orders, 1986. d8b101ba-b7d8-ef11-a730-7c1e527e6da9. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c32c7993-d5cd-4e9d-99af-cf72692f26da/order-approving-coffee-countys-settlement-orders. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

TN / /

® Elen. if /®,

Rl MU” FILED

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF ALABAMA OCT 30 1986

NORTHERN DIVISION paw

LIVIA

US DisT. Count

f MIDDLE DIST. OF AL’.

JOHN DILLARD, ET AL., DEPUTY CLERK, BY

Plaintiffs,

v. CIViL ACTION NO. CV 85-T-1332-N

CRENSHAW COUNTY, ALABAMA

ET-AL.,

N

a

s

t

?

N

e

e

s

N

e

e

”

N

a

a

t

M

e

e

t

?

a

t

t

?

e

a

e

?

ae

ra

?

“

a

t

”

“

e

a

?

”

Defendants.

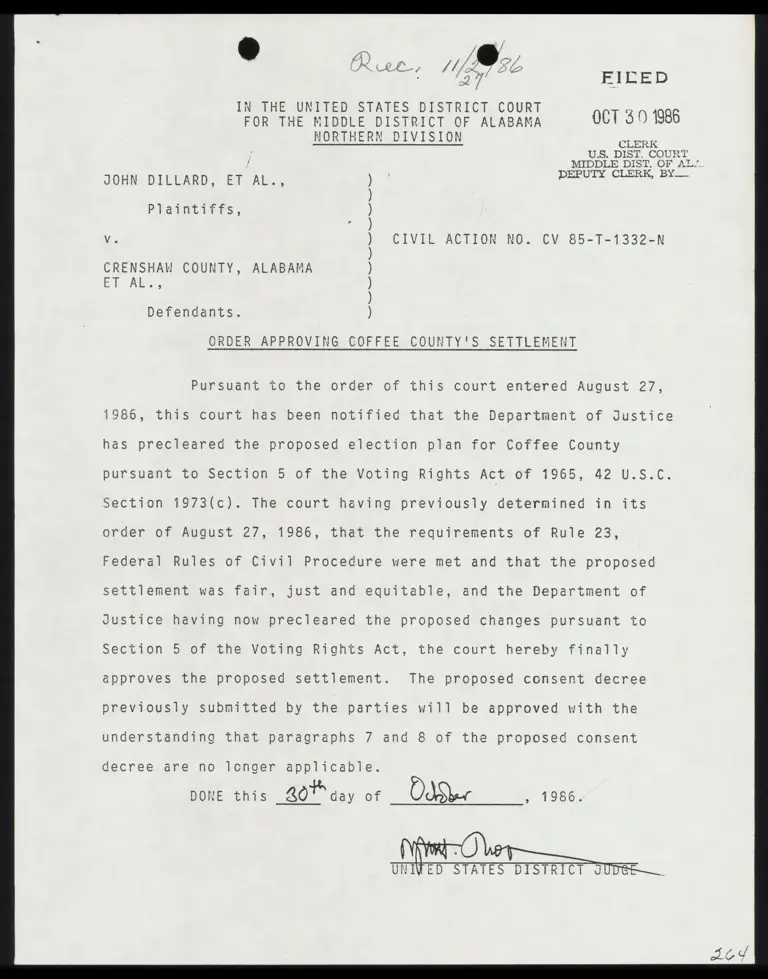

ORDER APPROVING COFFCE COUNTY'S SETTLEMENT

Pursuant to the order of this court entered August 27,

1686, this court has been notified that the Department of Justice

has precleared the proposed election plan for Coffee County

pursuant to Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 11965, 42 U.S.C.

Section 1973(c). The court having previously determined in its

order of August 27, 1986, that the requirements of Rule 23,

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure were met and that the proposed

settlement was fair, just and equitable, and the Department of

Justice having now precleared the proposed changes pursuant to

Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, the court hereby finally

approves the proposed settlement. The proposed consent decree

previously submitted by the parties will be approved with the

understanding that paragraphs 7 and 8 of the proposed consent

decree are no lcnger applicable.

DONE this Ae uy of DIL, J 1986.

UNIVED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE

ZL

% » FILED

IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES FOR THE 0CT 2 7 1986

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF ALABAMA, NORTHERN DIVISION

J HOMAS C. CAVER, CLER:

JOHN DILLARD, et al., )

) DEPUTY CLERK

Plaintiffs, )

)

Ve ) CIVIL ACTION NO. 85-T-1332-N

)

CRENSHAW COUNTY, etc., et al., )

)

Defendants. )

ORDER

For good cause, it is ORDERED that the October 24, 1986, motion

for summary judgment filed by defendants Ann Tate, et al., is denied.

DONE, this the 27th day of October, 1986.

UMITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE ~

® »

FIIL.ED

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

NORTHERN DIVISION OCT 2 7 1986

THOMAS C. 2AVER, CLER;

JOHN DILLARD, et als, * BY :

DEPUTY CLERK

PLAINTIFFS, *

VS: * CASE NO. 85-T-1332-N

CRENSHAW COUNTY, ALABAMA, *

et als,

requesting that election schedule to be ordered. The motion is not

opposed by the plaintiffs.

respect to the district elections, called for by the Calhoun County

plan,

DEFENDANTS.

ORDER

The Court has considered the Motion of Calhoun County

It is therefore ORDERED, ADJUDGED and DECREED that with

the following schedule will be implemented:

l. Noon, October 31, 1986, end of qualifying

2, November 18, 1986, party primaries

3. December 9, 1986, run-off elections

4, December 30, 1986, general election

DONE this 27th day Of October, 1986.

(i=

0.:S. DISTRICT JUDGE ~~.

® s i /

A) x » 4 - 7) Io) i

Fata Pl EL ED

IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES FOR THE

0CT 23 1986

THOMAS C. CAVER, CLER:

¥

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF ALABAMA, NORTHERN DIVISION

a SR nt SL

PEPYTY eLpnK Kis

JOHN DILLARD, et al., )

Plaintiffs, )

v. 4 CIVIL ACTION NO. 85-T-1332-N

CRENSHAW COUNTY, etc., et al., )

Defendants. )

ORDER

The Calhoun County defendants have orally requested that the court

clarify whether its October 21, 1986, judgment and injunction requires that

all five commissioners under the county's plan be elected by single-member

districts under new primary and general elections conducted prior to January

1, 1987. Upon consideration of the request, it is ORDERED and DECLARED that

all five commissioners under the plan for Calhoun County should be elected

by single-member districts under new primary and general elections conducted

prior to January 1, 1987.

DONE, this the 23rd day of October, 1986.

PA ovens

UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE = —