Memorandum from Hall to Liebman

Working File

July 26, 1984

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Memorandum from Hall to Liebman, 1984. 43ff9fe8-df92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c3d3b67b-7dc3-4476-9cfc-f5494b019bae/memorandum-from-hall-to-liebman. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

A(ro)

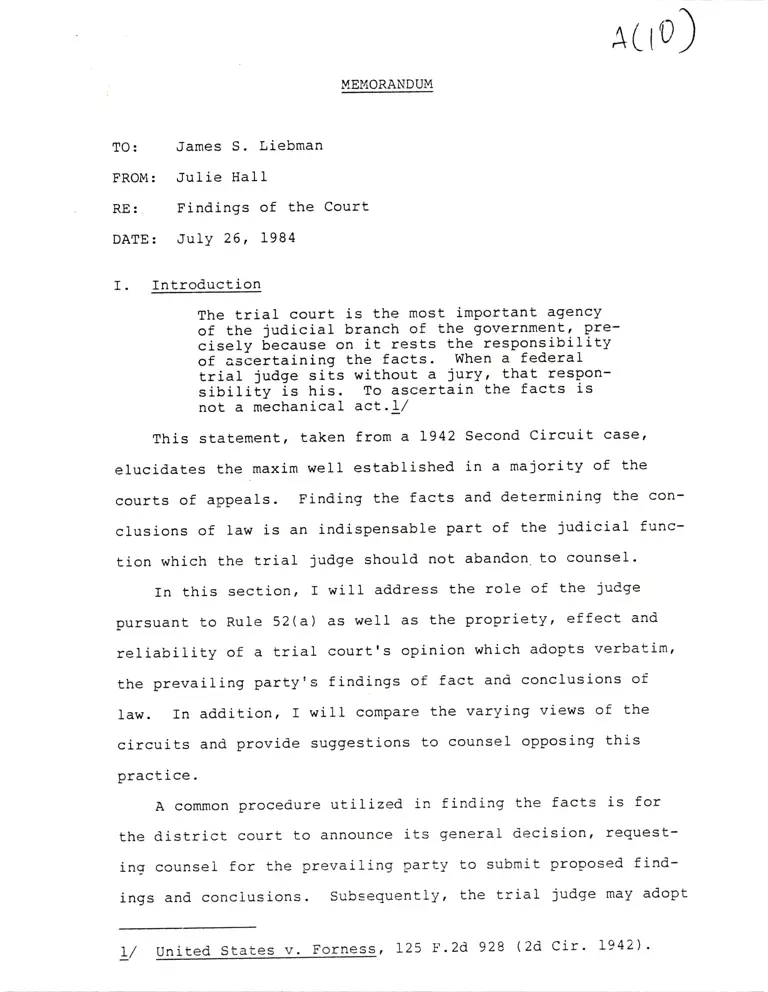

MEMIORANDUM

TO:

FROM:

RE:

DATE:

James S. Liebman

JuIie Hall

Findings of the Court

July 26, 1984

I. Introduction

The trial court is the most important agency

of the judicial branch of the governmentt-Pre-

cisely because on it rests the responsibility

of aslertaining the facts. When a federal

trial judge sits without a jury, that respon-

sibilily is his. To ascertain the facts is

not a mechanical act-L/

This statement, taken from a L942 Second Circuit case,

elucidates the maxim well established in a majority of the

courts of appeals. Finding the facts and determining the con-

clusions of law is an indispensable part of the judicial func-

tion which the trial judge should not abandon. to counsel.

In this section, I wiII address the role of the judge

pursuant to RuIe 52(a) as well as the propriety, effect and

reliability of a trial court's opinion which adopts verbatim,

the prevailing party's findings of fact and conclusions of

law. In addition, I will comPare the varying views of the

circuits and provide suggestions to counsel opposing Lhis

practice.

A common procedure utilized in finding the facts is for

the district court to announce its general decision, request-

ing counsel for the prevailing party to submit proposed find-

ings and conclusions. Subsequently, the trial judge may adopt

L/ united states v. Forness, L25 !'.2d 928 (2d Cir. L942)

those findings with minor revisions without giving any formal

opportunity to opposing counsel either to submit alternatives

or object to proposed findings before their adoption. The

Supreme Court in United States v. El Paso Natural Gas Co., 376

U.S.651(1954),vehementlycriticizedatrialjudge'smechan-

ical adoption of the findings of the prevailing party. The

court quoted at length from a statement made by Judge J.

Skelly Wright:

I suggest to you strongly that you avoid. as

far ii you poisibly can simply signing what

some lawyer-puts under your nose. These law-

yers, and properly Sor in their zeal and

ldvocacy and their enthusiasm are going-!o-

state t[:e case for their side in these find-

ings as strongly as they possibly gan' When

these findingi get to the courts of appeals

they \,/on' t be worth the Paper they are

wrilten on as far as assisting the court of

appeals in determining why the judge deci-

ded the case.2/

on June 5, 1984, District court Judge Russell Clark

issued a lengthy Memorandum and Order of decision which

announced its ruling that defendants, suburban school dis-

tricts, had not contributed, either individually or in concert,

to the segregated school system in Kansas City, llissouri' The

Order concluded that interdistrict relief must be denied and

3/

granted the Rule 41(b)-' motions filed by: Blue springs

2/ At L66, quoted from seminars for Newly Appointed united

States District Court Judges ( 1963 ) .

3/ The Advisory Committee Note to the 1948 Amendment of Rule

5'Z(a) added. the last sentence (findings of fact and conclu-

sions of law are unnecessary on decisions except aS pro-

vided in RuIe 41(b) to remove any doubt that findings are

necessary pursuant to Rule 4f(b). This rule provides that

2-

Reorganized School District, Grandview Consolidated School

District, Hickman Mills SchooI District, Independence SchooI

District, Lee's Summit Reorganized School District, Liberty

School District, North Kansas City School District, Park Hill

Reorganized School District and the Raytown Consolidated School

District.

In reaching this decision, Judge clark stated that the

court "reviwed the entire ,""ord,,!/ and has reached its judg-

ment after consideration of the live testimony, the demeanor,

believability and credibility of the witnesses, 4lI of the

exhibits, the designated depositions and the interrogatory

answers filed by the plaintiffs." However, after a thorough

comparison of the proposed findings of fact submitted by coun-

sel for the defendants with the actual findings made by the

court, it is undisputed that the trial judge adopted almost

verbatim and in toto the proposed findings submitted by the

1/ Continued

in a nonjury case the court mdlr if it sees fit, determine the

facts on a motion for dismissal, &t the close of the plain-

tiff's evidence. If the court grants dismissal at this point,

that rule expressly requires that findings be made -as provided

in Rule 52(al. These findings will not be reversed on appeal

unless clearly erroneous. See also: 9 Wright & I\'liller, Fed-

eral Practice and Procedure, Civil S 237I (I97I); ShulI v.

Dain,KaImaneQuai1,Inc.,551F.2dL52,I54(8thm9.77),

tral BeII TelePhone Co., 5I8 F'2d

68 (5th Cir. 2d 234 (8th

Cir. 19 ).

The record consisted of highly disputed evidence, includ-

g testamentary as well as documentary evidence, totalling

froximately 22,OOO Pages. In addition, there were over 2,I00

iribits, teltimony fiom I40 witnesses, and 10,000 pages of

positions. As directed by Rule 52(a), the District Court

itended it made specific, detailed findings of fact in suP-

rt of its judgment with page citations to the 55-volume

anscript and 130 dePositions.

4/

?ln

ap

ex

de

co

Po

tr

3-

5/

defendants.- The differences in the two documents are minor

involving only a condensation of the proposed findings by the

6/

trial Court.:' So far as the record reveals, counsel for

plaintiffs were not invited to comment upon nor amend the pro-

posed findings either before or after their submission to the

7/

court nor submit its own Proposals.-' Counsel for plain-

tiffs contend that these findings are entitled to little or

no weight upon review by the appellate court as they: I) are

not supported by the evidence, and 2) fail to afford the appel-

Iate court a clear understanding of the trial courtrs decision.

I1. Overview--A,Trial Cogrt's Verbatim AdoPtioE of

a t'lqre Critical

There is sufficient authority that the district court

may adopt without change those proposed findings of fact and

conclusions of law which are carefully prepared and supported

8/

by evidence in the record.=' Although such a practice, in

1/ See Appendix for Section G which compares !h-e P-rop9:eq. f ind-

ii.rg= submiitea Uy counsel for the defendants with the findings

ad5pted by.the triat court. The district court's findings of

faci were identical or substantially similar to the findings

proposed by the defendants

g/ In its Memorandum and Order, the district court condensed

fne 493 pages of defendants' proposed findings into 105 Pages,

deleting-onty redundant and extraneous materials.

Z/ According to 52(b), upon motion of a party made not later

fhan IO days after entry of judgment, the court may amend its

findings oi make additional findings and amend the judgment

accordingly. The motion may be made with a motion for a new

trial puisuant to Rule 59. However, this is not a requirement

for appellate review.

9-/ Roberts v. RosF r eilpla. _ !-, Br-adlev, y. l4arvla}d- 9a.s.ua1tv

do.,ffigth-m. Lr T),-whEre the court held that

4-

itself, constitutes neither a denial of constitutional rights

e/

nor reversible errorr=' a majority of the circuits have

expressed disaPproval of the practice

counsel's proposed findings verbatim,

Idaho L982) i Childs v. l,oca

; N.L.R.B. v. Webb

of

L0/

mechanically adopting

and have cautioned

9/ Continued

there was no deprival of any constitutional right or anything

which warranted reversal of the case as the result of the

courtrs verbatim adoption of the prevailing party's factual

findings and conclusions of law when they were carefully drawn,

in detiil, and in a professional manner and they related sPe-

cifically to the evidence in the record. Accor4: Photo Elec-

tronics Lorp. v, Englgnq, 581 F.2d 772, 77lffi, cim-

Circuit similarly expressed that "the

trial court's adoption of proposed findings does not, by itself,

trical Wo4<egg.,

-

F.2d

--

(9th Cir.

ffis fra 733,-757 (7th cirCir. 1982). The Fourth Cir-

affi recent case, EEOC v. Fedqral Reserve Baqk of Ric\

mond, 598 F.2d 633 (4th Cfr. f983); recognized that such a

praEtice; although disapproved, does not require reversal.

6nly one case, Nashville, C. a S,L.R- -Co. v. Price, 148 S'w'

2]-g (1911), ind :PrePared findings

was itself reversible error. However, the judgment was not

reversed because exception had not been taken on that ground.

But See: The Ninth Circuit case, Northern Stevedoring, etc.

v. Intern. Lo@n' s, 685 F .2d344 ( 9th Cir. 1982 ) , which

sale adoption of one side's submitted

findings of fact and conclusions of law invites reversal.

Uonethetess, the court failed to give further insight into what

factors would actually warrant reversal. Similarly, the Tenth

Circuit in Otero v. Mesa City VaIIey School District No. 51,

470 F. Supp. , 328 (D. CoIo. 9), citing G.M. Leasing v.

United Stltes, 5L4 F.2d 935 (10th Cir- L975), held that adop-

EIfrffiEngs prepared by counsel could lead to reversal.

But see, tn re-tai Colinas, 425 F.2d 1005 (lst Cir. 1970) (no

denial of due process ) .

2/ rd.

LO/ The Suoreme Court in United States v. El Paso Natural Gas

-tL

ffi. , 376 U:S. 651 ( 1954 ) , EEft-held that "where f indings are

ilEchanicalIy adopted, the reviewing court wilI disregard them."

Similarly, the First, Second, Third, Fourth, Fifth, Eighth,

Ninth and Tenth Circuits oppose this practice. See Section (B)

for a fuller discussion.

-5

the court of appeals to engag9 i".1 ,more

careful analysis of

Lt/

f indings prepared in this manner.- Ilowever, left unanswered

is when, if ever, this practice is impermissible and specify-

ing what, if anything, the appellate courts can do when this

occurs.

Rule 52(g) F.R.C.P. is self-executing. The duty of mak-

ing findings of fact and determining conclusions of law rests

L2/

with the trial court.-' In an action tried without a jury,

RuIe 52(a) requires the court to "find the facts specially

and state separately its conclusions of law" (emphasis

added ) .D/ In some circuits it is common practice for the

court to decide a case and then ask the prevailing party to

t4/

prepare the f indings.-' WhiIe the burden and resPonsibility

to make findings of fact and state conclusions of law are

LL/ EEOC v. Federal reservg Eank o{-Bigh$gnCl^sYPI?.at.-

lTtr, 2a 622 (roth cir'

igef ), cert. deniffi3, 454 U.S. 859, 70 L.Ed.2d

L57 ; il6ilffiuch-walker corp. , r. 2d ( 7th Cir.

Lg77l , 58rE2d 7'12, 777

(9th cir' rgz ' -64L F'2d

I35B (9rh Cir. f Se@aSa U.S. 1143, 102 S.ct-

IOO1 , 7L L.Ed.2d 294; ffi vlDorsev, 574 F.2d I3I, 149

( 3d Cir. 1978 ) .

L2/ 9 wright & Miller, S 2577 at 702 (r97I)'

L3/ FRCP 52(a). The rule by its very terms contemplates

6at the findings should be nmade" not "adopted" by the trial

judge.

L4/ Lindemann v. $merican Hgrist and Perficl-< CSr', 730

TqSz IcA Fad. 1984); Amstar Corp- v. Domino's Przza,

F.2d 552 (5th Cir. 19 ; In re Las Colinas, 426 F.

(Ist Cir. 1970); see also: Nordbye, Improvements

Sffiement of Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law,

25,30 (1940); 9 wright & Mi11er, S 2577 at 702 (197f

F.2d

Inc., 515

r005,

in

1 F.R.D.

).

6-

primarily upon the trial court, many courts recognize that the

prevailing party has "an obligation to assist a busy court in

performance of its duty under RuIe 52(a ).8/ Particularly in

complex cases involving scientific or technical issues, it has

been acknowledged that the proposed findings may indeed circum-

vent judiciar error .L6/

Nonetheless, since findings of fact are not set aside

unless "clearly erroneousr" RuIe 52(a), at least in part, is

designed to aid al. litigants and appellate court by affording

each a clear understanding of the ground or basis of the trial

court's decision. Not only do these findings aid the

appellate court on review, but they are also an important fac-

tor in the proper apPlication of the doctrines of estoppel and

res judicata in future cases .L8/ Further, the seemingly most

important purpose served by RuIe 52(a) is to evoke care on the

Le/

part of the trial judge,in ascertaining the facts.- This

rationale is consistent with the duty imposed by the RuIe.

Criticisms launched by the circuits opposing the mechan-

ical adoption of counsel's factfindings seem to have three

bases: I) preparation of findings in this manner usurps the

20/

judge's duty imposed by RuIe 52(a)-' in that these f indings

fail to insure to the appellate court that the trial judge

considered all the factual questions thoroughly and that each

finding is his impartial determination; 2) that, in addition,

such findings do not adequately inform the court on appeal or

the parties involved as to the bases of the trial judge's

. 2L/decision;:-' and 3) findings adopted in this manner are likely

L7/

7-

to convict the judge of error because they may be inadequate

to support his decision either due to their argumentative

nature or lack of substantiation in the record. (This criti-

cism accords with the intent of Rule 52(a) found in the L946

Advisory Committee Notes which estab.lish that "these findings

should represent the judge's g determination and not the

often argumentative statements of successful Counsel - " The

Committee Notes reaffirm that Rule 52(a) was not intended to

delegate to the prevailing par.ty the trial judge's primary

duty under the rule, namely, to "find the facts specially and

state separately its conclusions of law thereon.")

Such results can usually be avoided by following the better

practice of requesting proposed findings prior to the decision

22/

and making the request of counsel for both sides.- This

.widely accepted method allows the trial court to carefully

consider, weigh and determine the accuracy of the findings

submitted by counsel and to decide whether they are supported

by evidence in the record before him. In turn, this would

minimize the possibility of party preference and insure inde-

pendent judicial scrutinY.

23/

Regardless of which practice is adopted,-' the provisions

of RuIe 52 establish that findings of fact shall not be set

24/

aside unless "clearly erroneous."-' If the trial court has

not independently set out its findings, the reviewing court

may more readily be left with a definite and firm conviction

that a mistake has .been committed .25/ Although the practice

of verbatim adoption of findings prepared by counsel is not

25/

commendable, such findings wiIl not be summarily rejected.-

1i

,ll

JI;

8-

Nonetheless, to insure that the trial court has adequately

performed its judicial function, it is strongly suggested that

the adopted findings be supported by the evidence after a

critical scrutinization by the appellate court.

G. FINDINGS BY THE COURT

A. Adoption of the Prevailin Part 's Findi S

of Fact nclusions o Law: View That

Practice Is Proper Where ind s Scrutin zed

bv Judqe Before Signing

The sixth, seventh and D.c. circuits unanimously

assert that it is not improper for a judge to request counsel

for the prevailing party to prepare and present to him a state-

27/

ment of the f indings and conclusions of law.-' They conclude

that as long as the findings are supported by substantial evi-

dence, it makes no real difference which counsel submitted

them. This use of findings prepared by the prevailing party,

a procedure described by the Seventh Circuit as of "consider-

able assistance" to the trial court is defended at length as

following a practical and wise custom to assist a busy court'

The desired effect is to expedite the judicial Process without

compromising the rights of the litigants.

These three circuits argue that, ultimately, the proposed

findings should be considered merely an aid or assistance to

the court and solely within the court's discretion to adopt

and incorporate any or all of them in its opinion. In a recent

case, the Seventh Circuit declared that although as a "general

rule they do not endorse such a practice, they recognized that

it is within the discretion of the finder of fact so to do."

N.L.R.B. v Webb Ford, Inc., 589 F.2d 733 (1982 ) . See a1so,

9-

Lockte Coro. v. Fel-Pro, Inc-, 667 F.2d 577 (7th Cir' 198I);

Scheller-Globe Corp. v. Milso Manufacturinq Co', 636 F'2d L77'

178 (7th Cir. 1980).

Most of the cases which have expressly or impliedly

asserted this stance assume the trial judge thoroughly exam-

ined the proposed findings and affirmed they correctly reflect

the facts as he found them to be .28/ In the absence of indi-

cations to the contrary, appellate courts presume that such

perusal has been performed, thereby precluding closer scrutiny

by the reviewing court. The underlying assumption being that

,'the prevailing party's proposed f indings shoutd be given the

2e/

same weight as findings actually prepared by the court--

Further, these circuits assert that complaints with regard

to the findings--that they were "ex parter" "Self-servingr"

or one-sided are remedied by RuIe 52(b) of the Federal Rules

of Civil Procedrr€r which they interpret, contemplated ex

parte findings. As discussed in the Introduction, Rule 52(b)

gives the opposing party an opPortunity to interpose objec-

tions or amendments within ten days after entry of judgment'

However, this argumentr 8S well as the others, are disingenu-

ous. (See Section B, Page - )

The sixth, seventh and D.c. circuits' seemingly 1o9ica1

remarks that findings proposed by the prevailing party and sub-

sequently adopted by the trial court should be given the same

weight, reliability and effect as findings independently pre-

pared by the trial judge, falls Prey to the clear weight of

the circuits' case law with the intent and letter of RuIe 52(a)

30/

which hold to the contrarY.-

IO

B. Adootion of the Prevailinq Party's Findings

ii

Aooellate Courts

A trial court's practice of announcing its decision

then requesting the prevailing party to prepare the findings

which the district court adopts almost word-for-word in suP-

port of its decision is disapproved in varying degrees by an

overwhelming majority of the circuits. (The present applica-

tion of the RuIe in the Eighth circuit is stressed in this

section. This selectivity is to illustrate the problems that

exist in alI federal appellate courts')

The reason for such disapproval is inherent in the plain

meaning of Rule 52la) , Fed.R.Civ.P., a f air compliance which

,'requires the trial court to find the facts on every material

issue, including relevant subsidiary issues, and to rstate

separately' its conclusions of law with clarity-" De Medina

v. Reinhardt, 686 F.2d gg7, 1011 (D.C. Cir. 1982). As the

court in lilly v. Harris-Teeter Super Markets, 720 F'2d 326,

335 (4th Cir. 1983), said in language quoted and approved in

EEOC v. Federal neser@, 698 F.2d 633, at 640

(4thCir.1983),''thefindingsmustbebasedonsomethingmore

than a one-sided presentation of the evidence , ... [because)

finding facts under Rule 52(a) requires the exercise by an

impartial tribunal of its function of weighing and appraising

evidence offered, not by one party to the controversy alone,

but by both." See to the same effect: 1945 Advisory Committee

Notes.

I1

It is assumed that "the clear words of the statute ought

to be given their ordinary meaning in accord with the manifest

intent of the legis}ature," Lewis v. U.S., 445 U.S. 55 (1980).

when viewed in light of the common understanding of the phrase

"Rule 52(a) requires the trial court to find the facts ... "

coupled with the Advisory Committee comments make it patently

clear that the "court" is the sole arbiter of finding the

facts and determining conclusions of law. To read the RuIe

otherwise is to contravene the drafterrs clear intent as

expressed in the comment accompanying the RuIe.

While this application of Rule 52(a) does not require the

trial court to make findings on all facts or address every

argument made during the ProceediDgs, it does mean that the

reviewing court "deserves the assurance given by even-handed

consideration of evidence of both parties that the trial judge

32/

has settled alI irreconcilable confticts in the evidence."-

EEOC v. Federal Reserve Bank of Bishrnond, -ggpra. at 541 (4th

Cir. 1983), quoting GoIf Citv, Inc- v. Sportins Goods Co',

Inc., 555.F.2d 426, 435 (5th Cir. L9771; Askew v. United

states, 580 F.2d L2O6 ($th Cir. 1982); Garner v. st. Louis

Southwestern Railwav Co., 676 F-2d L223, L278 (8th Cir' L982)i

and Tate v. Weyerhauser Co., 72L F.2d 598, 605 (8th Cir. 1983.

In addition, when the trial judge adopts the proposed

findings of counsel, the court's thought processes may be cast

in doubt; thereby leaving the reviewing court without a clear

understanding of the trial courtts basis for decision. This

criticism was reconf irmed by the Third ,tt/ eighth4/

^nd.35/Tenth-' Circuits' strong disapproval of a district court's

-L2

mechanical adoPtion of

because theY "fail to

court's decision .36/

the proposed findings specifically

reveal the discerning line for the trial

Similarly, in a recent Sixth Circuit

case, Foulks v. Ohio t. of Rehab. a Correction, 713 F.2d

L2Lg, L233 ( 1983 ), the court remanded for more complete find-

ings as the findings of fact and conclusions of law failed to

provide the appellate court with a sufficient basis for re-

37/view.- Although:

In most cases it will appear that many of the

findings proposed by one or the other of the

parties are fully supported by the evidence,

are directed to material matters and could

(sic) be adopted verbatim, and in some

cases the findings and conclusions proposed

by a party will be so carefully and obj99-

tively prepared that they could (sic) all

propeify Ue adopted by the trial judge with-

out change,38/

does not guarantee that each word in the court's opinion was

3e/

impartially and independently chosen- as required under Rule

52(a), resulting in an allegation that the weight and relia-

bility of such findings is doubted. A1I of these considera-

tions prompted the Supreme Court in U.S. v. Crescent Amusement

co., 323 U.S. L73, 184-85 (1944), to comment that the adoption

of findings (proposed by the prevailing party and subsequently

adopted by the trial judge) "leave much to be desired in light

of this function of the trial court under Rule 52(a)."

Most assuredly this is because "important evidence is likely

to be overlooked or inadequately considered when factual find-

ings are not the product of personal analysis and interpreta-

tion by the trial judge," Jones v. International Paper Co., 720

F.2d 496 (8th Cir. 1983), citing James v. Stockman Valves &

I3

Fittinq co., 559 F.2d 310, 314 n. I (5th Cir. L977), cert.

denied, 434 U.S. 1034, 98 S.Ct. 767, 54 L.Ed.2d 781 (1978).

The Eighth circuit's Position on the use of Proposed

findings has undergone a transition in recent years' Early

Eighth Circuit cases, although not directly addressing the

propriety of this practice, Iaid the foundation for determin-

ing the judge's function pursuant to Rule 52(a). Brown Paper

MiIICo.,Inc.v.Irwin,I34F.2d337,(SthCir'1943)'

noted that "findings of fact should be a "clear and concise

statement, not a report or recapitulation of evidence from

which such facts may be found or inferred." In Sliellv Oil v'

Holloway, L71 F.2d 670, 673 (8th Cir. 1948), citing Brown'

infra, the court confirmed that the rule is "intended to aid

the appellate court by giving a clear understanding of the

basis of the trial court's decision" (emphasis added)'

Ilowever, in 1949, contrary to the plain language and

rationale of the Rule, this Circuit refused to disapProve of

the practice of having proposed findings and conclusions pre-

pared by prevailing counsel without notice to the other side'

Miller v. Tillev, L78 F.2d 526,528 (8th Cir. 1949). In this

case, the court, agreeing with the view of the sixth, seventh

and D.C. Circuits, noted that "the practice is common and con-

ventional in many jurisdictions" and that "whatever method Iis

usedl (sic), the trial judge assumes ful1 resPonsibility for

the findings made or adoPted. "

Ten years after the decision

a gradual move to disaPProve this

in Miller, this Circuit made

I4

practice4/ *r,i"h deveroped

4L/

into ',Severe criticism" by L957.-' In Bradley, counsel for

the defendants were requested to prepare its findings and

conclusions to assist the trial court. Except for two retyped

pages, the court's supporting memorandum adopted wholesale the

findings prepared by^ counsel. After reiterating the purpose

of the rule, the court did not reject the findings. Quoting

from the Lg64 Supreme Court decision, United States v. El Paso

Natural Gas Co., 376 U.S. 65I, 656, 84 S.Ct'. L044, 1047, L2

L.Ed.2d 12 (1964), the court concluded that such findings,

"though not the product of the workings of the district courtrs

mind, are formally his; they are not to be rejected ou.t-of-

hand, and they will stand if supported by evidence"'

The court held that the findings and conclusions were

supported by evidence as they were "drawn carefully, in detail,

and in a professional manner, and they related specifically

to evidence in the recordr " at 423. As a result, the court

rejected allegations that this practice alone deprived either

party of any constitutional right or warranted reversal.

However, "if for some reason, counsel must be asked to

assist in the preparation of findings and conclusionsr" the

approach as suggested in Brad1ey, is to make this request of

both sides at or soon after the submission of the case and

prior to the decision. 5 lr{oore's Federal Practice (2d ed.

Lg66), par. 52.05[3], p. 2665. IdealIy, this enables the

court to select portions of the findings which coincide with

its concept of the case.

15

Subsequent Eighth

sis in BradIeY, PaYing

Circuit cases have followed the analy-

close attention to the manner in which

42/

the findings were made.-

Most recently, in Jones v. International Paper co., 720

F.2d 4g5, 4gg (1983), citing Askew v. united states' 580 F'2d

L206, L2O9 (1982'), the Eighth Circuit reaff irmed its avid

disapproval of the "court placing its imprimatur on such find-

ings by wholly adopting them as the court's own." while the

Eighth circuit in Askew, Et 1209, recognized that "submis-

sion by counsel of proposed findings is frequently a valuable

decisionmaking aid to the court, " this court stressed that the

adequacy of such findings is placed in question for three rea-

Sons. The overall result may be that "losing counsel may for-

feit his undeniable right to be assured that his position

has been thoroughly considered. Additionally, the independence

of the court's thought Processes may be cast in doubt and,

tastly, the reviewing court may be left without a clear under-

standing of the trial courts basis for decision. " AIlied van

Lines, Inc. v. Small Business Administration, 667 P'2d 75L,

753 (8th Cir. 1982).

Despite these valid criticisms, the court again acknow-

tedged that the find.ings are formally the district judge's and

will stand if supported by the evidence. It can be inferred

from the holding in Bradley and its Progeny, that the Eighth

circuit follows a broad interpretation of the Rule subjecting

the findings to the "clearly erroneous standard, regardless

of who prepares them. " This view supports the primary and

I6

basic test of the adequacy of findings. Note: Counsel rely-

ing on the Eighth Circuit's view of this procedure, will make

the strongest argument by establishing that the findings are

not supported by the evidence. In the Eighth Circuit the

practice of adopting the proposed findings verbatim, bY itself,

does not warrant reverSal, and in very few cases has even war-

ranted a remand. See: Tate v. Weyerhauser, '723 F.2d 598, 505

(8th Cir. 1983). (In this Title VII action, dlthough the Dis-

trict Court made no sPecific finding regarding one incident

highlighting appellant's disparate treatment, reversal was not

warranted. See also, Garner v. St. Louis Southwestern Railwav

Co., 676 F.2d 1223, L228 (8th Cir. 1982).

43/

Similarly, the Third Circuit- while strongly disapprov-

ing this practice, permits the use of findings drafted by

counsel on a conditional basis. In Roberts v. Ross, 9!.PI9,

the court agreed with the better practice of inviting counsel

for both parties to submit proposed findings of fact and con-

clusions of law. However, there was one caveat. Onlv if the

trial court solicits and considers the findings from both

sides *a- to its decision on the merits will the Third Cir-

cuit permit such a practice.

Otherwise "findings and conclusions prepared by a party

and adopted by the trial judge without change are likely to

be looked at by the appellate court more narrowly and given

less weight on review than if they are the work product of

the judge himself. " Roberts v. Ross, supra at 751. Confirming

L7

this view, Judge Albert B. t'lans, speaking for the Third cir-

cuit in RobertE-l:- Ross, .W, recognized that RuIe 52 (a )

requires the trial judge to formulate and articulate his

findings of fact and conclusions of law in the course of his

decision-making Process -

44/

consistent with this observation is the Fifth- and

45/Tenth- circuit's view that the mechanical adoption of sub-

mitted findings of fact and conclusions of law, though not

proscribed by either circuit, is an abandonment of the duty

imposed by RuIe 52, because they may fail to disclose the

court,s rationale for its decision. (This coincides with the

Eighth Circuit's criticism of this procedure') In fact' both

circuits require a critical scrutiny of the adopted findings

by the appellate court to insure that the trial court has

adequately performed its judicial function. The inadequacy

of the verbatim adoption of defendantrs findings htas most

apparent in Ramey, i@, wherein complex factual allegations

and legal theories were dismissed in a conclusory manner

resulting in remand. for new, more detailed findings.

The wholesale adoption of proposed findings, sanctioned

in appropriate cases by these two circuits, is "vehemently

46/

opposed', by the Second Circuit-' and selectively approved in

47/

"highly-technical" and "complex" cases in the First- and a

48/

Ninth-' Circuits. The First and Ninth Circuits seemingly

offer the most logical explanation for the verbatim adoption

of proposed findings. while the First circuit in In re Las

Colinas, restricted the mechanical adoption of proposed find-

ings to ',extraordinary cases," the Tenth circuit in Ramey,

18

infra, distinguished between the technical complexity of a

case and complexity through sheer volume. In Ramey, even a

trial lasting six weeks producing an immense record of fifty-

five volumes, including thousands of pages of transcript did

not render them (sic) inherently complex to justify verbatim

adoption, at 458. See also: Photo Elec. corp. v. England,

581 F.2d 772, 777 (9th Cir. 1978); Kaspar .Wire Works, Inc' v'

Lees Ens'r e Mach., Inc., 575 F.2d 530, 543 (5th Cir' 1978);

520 (7th Cir. I97I); In re Las Colinas, infra

, 447 P .2d.',5L7 ,

, Et 1009.

Although cognizant of the "clearly erroneous Standard"

of Rule 52(a), the Court of Appeals in the Fourth Circuit

case, Cuthbertson v. Bigqers Brothers, Inc',

-

F'2d

-(1983) (on writ of certiorari), believed it should decide the

case de novo, solely becairse the district court had adopted

findings in essentially the form proposed by plaintiff's coun-

seI. Based on the proposed findings submitted in this Title

VII action, the district court entered judgment enjoining the

defendant from practicing racial discrimination against the

four-named employees.

on appeal, Judge Widener repeated the Fourth circuitrs

admonition of the practice of adopting the prevailing party's

proposed findings of fact and conclusions of law and concluded

that the use of the practice, itself, justified remanding the

case. The court further directed the district court to pre-

pare its own findings at the conclusion of the remand proceed-

ings.

Reese v. Elkhart We1din

I9

To suPPort

ANCE, 152 F.2d

this conclusion, the court relied on THE SEVER-

gL6, 9I8 (4th Cir.), cert- denied, 328 u'S' 853

(1945), thereby, according the findings "less weight and dig-

nity [than] ... the unfettered and independent judgment of

the trial judge."

4e/

The Fourth Circuit in a series of decisions,- has con-

demned the verbatim adoption of prevailing party's findings.

See: tliller v. llercv Hospital, Inc. , 720 F.2d 356, 369 (4th

Cir.1983);HoIsevv.Armour,5S3F'2d854,865(4thCir'

L982); EEOC V. Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, 598 F.2d 149

(4thCir.1983);Lillvv.Harris-TeeterSuperMarket'720F'2d

326 (4th Cir. 1983).

In light of the numerous court of appeals which disavow

the mechanical adoption of findings prepared by counsel, none

gives guidance as to how such findings should be treated on

50/ 5L/

appeal . While the Eighth-' and Fif th-' circuits apply the

',clearly erroneous" standard, regardless of how the f indings

52/ 53/ 5l/

were prepared, the Firstr-' Tenth-' and. Fourth-' Circuits

will remand a case for additional findings. Four circuits

apply a vascillating standard of review when this practice is

utilized. The First circuit makes a "most searching examina-

tion" for error and directing the reviewing courts in close

cases to feel more justified in remanding. In the Third cir-

cuit these findings are "looked at more narrowly and given

less weight on appeal," while the FifthE/ and Ninthff/ Cir-

cuits subject them to "special scrutiny' " Note: In a L979

case, the Seventh Circuit, although not disapproving of the

practice, stated it "wouId critically review the contested

20

f irraing=." Such a stance could indicate a shift from a uni-

Iateral approval of the practice to a wavering skepticism by

this Circuit.

part

and

The confusion and division among the

from the conflicting implications of

circuits may stem in

Crescent Amusement

EI Paso Natural Gas, supra.

The former case held that such findings "Ieave much to

be desired in light of the function of the trial courtr" yet

insisted that "nonetheless they are the findings of the Dis-

trict court and must stand or fall depending on whether

they are supported by evidence." 323 U.S. at 184-85- The

latter decision (citing crescent Amusement)r denounced the

verbatim adoption of proposed findings as "being less helpful

to the appellate court as they fail to reveal the discerning

Iine for decision of the basic issue in the cds€r" and not the

working of the district courtrs mind, Yet affirm that "they

are formally his and therefore not to be rejected out of

hand." 375 U.S. at 556-

In Iight of the apparent inconsistencies of Crescent Amuse-

ment and EI Paso Natural gas, a close reading reveals that these

two cases are reconcilable. EI Paso, citing Crescent, confirms

that the ultimate decision to accept or reject the findings is

whether they are supported by the evidence. However, both

cases use language from United States v. Forness to highlight

that these findings should ultimately reflect the judge's own

determination. Nonetheless, the Supreme Court has consistently

followed the comments of the Advisory committee with respect

to admonishing the practice of adopting the findings prepared

2l

Nevertheless r rlo court

of announcing its decision

prevailing PartY to submit

tionr ds reversible error-

by prevailing counsel. In effect, the supreme court in its

infinite wisdom discourages the mechanical adoption of find-

ings, but yet acknowledges that the trial judge is ultimately

responsible for the findings made. seemingly, unless counsel

opposing such a practice "overcomes the heavy burden of show-

57/

ing that the findings of fact are clearly erroneous,"- they

should stand as adoPted.

Note to counsel: Counsel should make note of the fact

fffi in Er Paso consisted 1ar9e1y 9f undis-

pot.a evidence. rt-Effird consisted of highly dis-

iuted evidence, it is speculatitg.whether the Supreme

Court would have had sulh a cavalier attitude towards

the mechanical adoption of findings prepared by the

pi"".iling party. Counsel opposing this practice

Lou1d mak6 i muln stronger cise if he can distinguish

the record in El PaEo with the case at bar'

regards a trial court's Procedure

first, and then asking onlY the

written findings for their adoP-

Nor does it mean that the "clearlY

erroneous" rule will not be apptied. However, what it does

mean is that this procedure can be systematically challenged

in hopes of securing a remand.

To accomplish this result, counsel opposing the wholesale

adoption of prevailing party's findings should make the fol-

Iowing arguments.

22

4, bnL

n 'LS

"r'('t

Y

. c. suggestions to couqsel: The Practice of the

he Prevailing PartYrs

Findings Verbatlm Is Against the Clear Weight

of the Case Lar,v, Contrary to the Intent of

the Rule and Unequivocally Warrants Remand'

. An appropriate review by the court of Appeals is not pos-

sible if due to the District Court's failure to make adequate

58/findings,-' the reviewing court is left to speculate what the

District Court believed the facts to be or question the basis

for its judgment. Under such circumstances, regardless of the

exercise of a 52(b) motion, the court of Appeals must remand

the case and direct the lower court to make additional find-

ings. (See: Anthan v. Professional Air Traffic Controller

Orqanization, 672 F.2d, 706 (8th Cir. 1982), wherein a trial

court's findings that plaintiff incurred medical treatment,

without citing a dollar figure, was inadequate to afford the

appellate court an opportunity to review an award of comPensa-

tory damages thereby warranting remand for itemization in com-

pliance with Rule 52(a). )

Initially, counsel must establish that the court did

indeed adopt the prevailing counsel's findings verbatim paying

close attention to whether the wording of the judge's opinion

is a carbon copy of the prevailing party's findingsr oT made

with only a few inconsequential changes. Second, counsel

should make note of the relative number of findings so adopted.

(That prerequisite is obviously met in this case because .. " )

Note: In response to this allegation, any evidence that the

trial judge gave careful consideration to the party prepared

findings, such as where he deleted or changed some of the

A

23

findings r ot made additional findings, will redound to the

benefit of the prevailing party. Elowever, even when a district

court took "obvious care in editorial revisions to the proposed

findings, and added a critical finding on the ultimate motiva-

tional issue" in a Title VII case, the aPPellate court still

admonished this practice. See: Miller v. Mercy llospital, Inc. ,

720 F.2d 356,359 (4th Cir. 1983).

Additionally, counsel should highlight the method used by

the trial judge in preparing the findings. As commented in

both Lillv v. Harris Teeter (10th Cir. 1983 at Section G) and

Bradley v. Marvland Casualtv Co., SPE, the better practice

is to request findings from both parties prior to announcing

the decision of the trial court. Note: In Lilly, the District

Court did not fail to meet its obligation under Rule 52(a) to

find the facts specially and state separately its conclusions of

law when it, adopted essentially verbatim proposed findings sub-

mitted by counsel. In this case, the district Court (I) twice

specifically requested that defense counsel submit comments orlr

and objections to, the submitted findings

'

(2) reversed its

initial findings as to one intervenor; and (3) check cited evi-

dence in proposed findings against the actual transcript,

approving each paragraph of findings one by one. (ff such a

thorough examination of the factfindings is not performed

before adoption by the district court, then it can be presumed

that the judge adopted the findings without giving them care-

ful scrutiny. In addition, RuIe 52(a) was amended in 1983 to

Iighten the burden on the trial court in preparing findings in

24

nonjury cases. This amendment permits the judge to make find-

ings orally as required in nonjury cases. This in effect would

reduce the need for verbatim adoption of findings by the trial

judge. However, it is not clear where the judge requests

findings from both parties prior to announcing his decision and

then adopts the findings of one, if the losing party is estopped

from objecting to the practice because he participated by sub-

mitting findings. In resPonse, counsel should contend that

adoption rather than submission of findings is at issue, there-

fore estoppel in such a situation would be misplaced.

2. Remind the appellate court of the duty imposed on the

trial judge pursuant to RuIe 52(a) and argue that this duty

would be usurped by this practice. (See: Section G(B) for the

circuits which espouse this view. ) This argument could be but-

tressed by reference to the Advisory committee Notes of 1945

as well as to the Model Code of Judicial Responsibility, Canon

2, which explicitly states that "the independence and integrity

of the judiciary is the touchstone of the democratic process - "

(This argument is especially reinforced in the instant case

where a RuIe 41(b) motion was granted. Remand is required

where the trial court fails to make findings to support its

dismissal. The impetus for a remand is reinforced since the

court of Appeals is restricted from reviewing the evidence de

novo or make its own findings. Finnev v. Arkansas Board of

Correction, 505 F.2d 194 (8th cir- L974).

A 1980 district court case in ltlassachusetts contended that

RuIe 52(a) requires courts to make far more detailed findings

25

3. As an aside to

also contend that when

lows counsel's findings

court's thought Process

of fact than a jury is required to make when the case is sub-

mitted to it under Rule 41. See: Banergee v. Board of Trustees,

495 F. Supp. Il48 (4th Cir. 1980). t?l

Recommendation * 2 above, counsel should

the wording of the judge's opinion fol-

CoIinas, supra. This is

verbatim, "the indePendence of the

may be case in doubt." In re Las

an obvious argument which should not

be lightly disregarded.

4. As a corollary to # 3 above, counsel should also

assert that ofactfinding is the basic resPonsibility of the

district court," PuIIman Standard v. swint, 456 U.S. 273,

2g2, 72 L.Ed. 2d 66, 102 S.Ct. I78I (1983). Therefore,

adopting verbatim the findings of the prevailing party is

tantamount to no findings being made by the district court,

thereby justifying remand with directions for further findings.

Although no case has actually asserted this view, this argument

may at least be one factor to prompt strict appellate review'

See: Roberts v. Ross, 344 F.2d at 752, to support this line

of argument.

5. Acknowledge, that most, Lf not all courts, in the

interests of judicial economy, can request the assistance of

counsel in preparing the findings. Nonetheless, sheer volume

does not justify the verbatim adoption of the prevailing party's

factf indings. (For example, 9E: Ramey, supra, a Tenth Circuit

case which produced over 55 volumes and thousands of Pages of

26

trial transcript, held that a voluminous record did not justify

verbatim adopltion of findings. The record in the instant case

is of comparable length and similarly does not warrant the

mechanical adoption of the findings.

6. Demonstrate any improprieties in the findings so pre-

pared which would have been changed by a judge who gave them

careful consideration. (This is probably counsel's strongest

argument in favor of remand. ) See: Cuthbertson v' Biqqer

Bros., supra, wherein the aPPellate court after giving careful

scrutiny and comparing the findings to the record concluded

that if the judge had given the findings his independent scru-

tiny, a different finding would have been made. (The argument

would proceed as follows: Whether the district court would have

come to exactly the same findings if opposing counsel had the

opportunity to introduce evidence is speculative. If plain-

tiff's counsel had been given the opportunity to demonstrate

the rationality of contrary findings, the district court would

have been forced to make a more critical examination of the

record. Therefore, the findings should be remanded. )

7. In the alternative, counsel should supplement the

allegation of error on ground # 6 with an allegation and argu-

ment that the findings are not supported by the evidence' If

counset loses the former issue on appeal, there is Possible

relief under this recommendation.

8. A majority of the circuits posit that the wholesale

adoption of the prevailing party's factfindings warrants closer

scrutiny by the aPpellate court. See: Section G(B). This

being the present state of the law, then if an appeal is involved,

27

much of the time saved to the trial judge, bY having the Pre-

vailing party assist the court by preparing the f indingsr IIIaY

be lost at the appellate leveI. The appellate judges who have

not had the benefit of hearing testimony in the case are forced

to scrutiny the record de novo to ascertain whether the

facts are supported by the evidence. Note: De novo review was

permissible for just this reason in the Fourth Circuit case:

Cuthbertson v. Biqqer Bros., supra.

This argument on first flush, mdY seem to undermine the

necessity of careful scrutiny by the appellate court. Never-

thelessr op closer examination, this exacerbates the extension

of precious judicial time 'and qnergy required when the trial

judge adopts the victorious party's findings, thereby under-

mining the acceptance of this method of preparing findings.

g. The making of findings is undisputedly a judicial

function which inherently conflicts with the adversarial pro-

cess. "proposed findings are adversarial documents designed

to present aII (the attorney's) contentions in the light most

favorable to their clients." Therefore, wholesale adoption

of such proposals by the court cannot generally convert them

chemical Corp., 437 F.2d 1336, 1340 n. 3 (9th Cir. 1971)' See

also: Advisory Committee Notes.

10. Further, counsel requested to submit findings does so

in a vacuum. The prevailing party must articulate and write

out findings of fact and conclusions of law without any knowledge

into a form "ref lecting impartialit'y and restrained, objective

judicial attitude." Industrial BIdq. Materials, Inc. v. Inter-

28

of the factfinder's reasoning Process. It is reasonable to

believe that submission of facts in this manner would give

the prevailing party an opportunity to relitigate his case.

This argument was advanced in the Fourth Circuit case, I"liller

v. ttercv Hospital, Inc., ESPIS.

1I. Lastly, counsel should address the assumption that

Rule 52(b) provides sufficient relief for the dissatisfied

party to amend the findings so adopted. This is a faulty

argument. As noted in EEoc v. Federal reserve co., E9PI3,

"(A)t this point the judge's decision, not the adversary's

proposed findings and conclusions, must be challenged, and

any fair opportunity to influence the decisional process in

the trial court in practical terms has been lost," at 369.

To reinforce the futility of the Process of filing a 52(b)

motion, counsel should note that post-finding objections or

motions to amend may be made, although they are not required

in order to challenge findings on appeal.

A combination of these arguments should be attempted to

induce the appellate court to at least more carefully review

the trial court's findings of fact. Hopefully, these sug-

gestions will warrant remand-

29

IFootnotes--beginning P. 7 -l

L5/ Schwerman Trl:ckinq 99r.Y. gaftl+nd 9lePmship--99. , 4?6-

{za

Co., 636 F.2d L77, I78 (7th Cir. 1980)- !!! see: I! r?

GTinas , Inc. , 426 F. 2d 1005 ( lst Cir - L967 ) , -cert. denied,

aGffi0E7,whereinthecourtacknow1edgedthattheprac-

tice of inviting counsel to submit proposed findings of fact

and conclusions of law is a valuable aid to decisionmaking,

however, recognized that the court's findings must ultimately

represent the findings' own determination.

A11 of these cases refer to the practice of requesting

findingsr ds a "practical and wise custom" of the adjudicatofy

systeml See also, Bradl,ey v. tlarylanl.Casualty C9. , 382 F.2d

a1s (8th ffiTgE'7 ) s custom, but disaP-

proves of the trial court's verbatim adoption of-the prevail-

ing party's findings of fact and conclusions of law. Accord:

Canon 5 of the Code of Judicial Conduct states that a EJu@

should dispose promptly of the business of the court." Expli-

cit in the Comm-ntary accompanying Canon 5 is the desire to

permit assistance from lawyers, court officials and litigants

to dispose promptly of the court'S business. Even a narrow

interpietation of Canon 5 would permit requests for findings

of talt and conclusions of law. However, whether under this

Canon the wolesale adoption of a prevailing party's findings

would expedite the disposition of a case is speculative.

L6/ This is acceptable in many coTplgl paten!_ cases - 9-: .

ilvvssonen v. Bendix CorP, , 342 F.2d. 53I, 532 (Ist Cir. 1965),

, 382 U.S. 847, 15 L.Ed.2d 86, a com-

fx paE;i-infringement case, wherein the court of appeals

icknowledged that in a highly technical and complicated case,

the trial court was justified in relying uPon counsel for

technical f indings. See also: In re L?s Colinag, Ing. , -4-2-9

F. 2d 1005, Io09 ( tst f[r. T970 ) ,-ggit. d.ni"d , 405 u. s - L067 ,

92 S.Cr. L502, 31 L.Ed.2d 797 (L972i, here the court decided

that the practice of adopting proposed findings verbatim

"should be Iimited to extraordinary cases where subject matter

is so highly technical it requires expertise which the court

does not possess. "

17/ A leading authority on federal practice stated that

Eeally f indings of fact should be clear, specif ic and com-

plete. 9 Wright & Miller, Federal Practice and Procedure

S Z57g ar 7II (197I). See also: U.S. v. Merz, 375 U.S. L92

(1964), in which the supreme court emphasized this function.

According to the Second Circuit case, Lora v. Bd..of Educ. of

the Citv of N.Y. , 623 F.2d 248, 25L (1980), a "tria} court

ffit to the task of sifting through the entire

record below to determine what facts support what conclu-

sions." Findings of fact should be explicit enough to give

the appellate court a clear understanding of the.basis of the

trial-Lourt's Oecision. See also.: Snyder v. United States,

674 f.2d 13s9 (10th Cir. 1980).

1-

L8/ Advisory committee Note to 1948 amendment of RuIe 52(a);

5-;.n.o. -it '{ft, citing Nordbye, Improvements in Statement of

rinaing" of Fact and conclusions of Law, 1940, I F.R.D. 25,

26-27; Wattleton v. Intern. Brotherhood of Boiler Makersr €tc.,

686 F.2d 586,

1199, _ U.S. _, 75 L.Ed-2d 442-

ls/ United States v. Birnbach, 400 F.2d 378 (8th Cir. 1968)'

fficor , 344 F'2d 747 (3d

Cir.1955),the''purposeoftffin9to.{indingsis

to require the ju&ge-to formulate and articulate findings.and

conclrisions in the course of his consideration and determina-

tion of the case and as part of his decision-making process,

so that he, himself, may be satisfied that he has dealt fully

ina properiy with atl i-ssues in the case before he decided it

and so that the parties involved and the reviewing court may

be fully informel as to the bases of the decision when it is

made. "

20/ United Stateq v. El Paso Natural Gas Co., 375 U.S. 551-(Tgoa@, 344 F.2d 747 (3d efi. 1955); Bradrev

v. r,rarvtffi. ,--382 F.2d 41s,.: l9!1, 9lt' L9571;

oeo F.2d L205, Lmg (8th Cir- 1982);

, 720-F'2d 496 (8th Cir' 1983)

a judge should uPhold the

TnGffiV and independence of the judiciary. Adopting lhe

piop5sea'f indings -ot the prevailing pafty comPromises his

indlpendence and compliance with Rule 52(a).

2l/ Al I ied Veq l,irce Inc. v. SmaIl Business Administration,

667 F. 751, th Cir. ) (citations omitt ,

stanlev v. Henger-son, 727 1- ?9_5:-l 1 9..-l-!'I:..1:'?il^-:'::::7:afford the reviewing court "clear under-

standinj of basis o? trial court's decision"; C59sE v. PgEIey,

267 F.2d 824 (8th Cir. 1959); United Statqs -Y' EI Paso, 376

u.s. 551 (1954), took notice tEE-wEere=Lndings are mechan-

ically adopted and fail to reveal the line for decision of

the bisic issue of the case, the reviewing court will disre-

gard them.

22/ 5 A. J. l,loore' s Federal Practice (2d ed. 1966 ) , par. 52.06

T3'l , p. 2665. [also see section G(B) ] . Accord: Brad]?y v.

lliivllnd casualiv cg. , suPf a i -Bobgf !s . Y.. R99s, !EqI?; !@- .tffit6W. 1e8r); Pf+iU

, 460 F.2d 1096 (5th Cir'

s followed bY trial courts

in adopting a prevailing plrty's findings. One practice includes

having p"r[ies submit tinaing!, the judge subsequently m"5!ing

each laiagraph of both sets eitfrer "found" or "refused"; (2)

beforl *atlitg at oral decision, having both parti"?-submit f ind-

ings and thei adopting the findings of.one party-; {3) making

an oral decision -for one party and having him submit findings

11

l

22/ Continrled

and(4)makinganoraldecisionforoneparty'givingtherea-

sons therefor, i"a having that party submit findings in accord-

ance therewith. Note: method number three most closely aPProx-

imates the procedlFused in the instant ca99.^.Lillv v'.Farri;:

Teeter Supermarket, 720 F.2d 326 (4t,h Cir. 1983), gives the most

common sense g[ffi".. for courts to follow in adopting proposed

findings. fnit decision suggested that "prior -to reaching and

.rr.ror,,.r6ing any decision, the trial court should request pro-

posea findingi from both parties as to all of the disputed

factual and l-gaf issues, with reference to the record suPport-

i"g the fact i6g""it.a and then prepare its decision based upon

ia; independent'analysis of the proposed findings. and the evi-

dence of record," at 332. Ideally, greater efficiency, more

iccurate findings and fewer appeals would result-

23/ See-footnote 22, suPra.

24/ F.R.c.P. 52la), cited in uliled 9!a!9:=vt -nl E?so 99:'. 2AA a:-i-I-72 I ort r.ie l Oai

fiffi; ,582F.2d s1o (sthcir'

I . i"PfPr

at ; Railex Co v Check Co., 7 8.2 040, ( 5th

Eir:-67 34 L'Ed' 2d t28 ' e3

S . Ct . 12 5 . Gve-f thilourt wai ted f ourteen months afourteen months afterNI€

the conclusion of trial to issue its ruling and -the- findings

*".. adopted, almost verbatim, the court aPplied RuIe 52(a) '

25/ Askew v. Unite4 Eta!,es, 58.0. F.2d L206, L209 (8th Cir.

Lg82), .ititg sum, 333 U'S' 364' 395

(1948). see . ,^-?60^I:2d 747 '

750 (3d Cir. 1958), 875, 359 U'S' 966'

3 L.Ed.2d 834;-"na'nEffirplv. =spee9

c!9cl 9o' '.457 E'2d

io+0, Lo42 (sirr cir , 93 s'ct' L25'

-u.s. 875,34 L.Ed.2d L28-

25/ U.S. v. EI Paso Natufal- Gas Co', sqpra-at. 1047' citing

U.S. v. Ct." ,-T6-nd that although find-

i reT6Tthe product -of . the district

courtrs mind, they cannot be rejected out of hand, but will only

stand if supporteif Uy evidence. See also: .RameY-9onslI. -99.,

i".. ". ep.ii.e T4!qsl-l4esc@, 6LG F'2d 464

(lOth Cir. I

Lrd., 593 P.2d 375, 382 (1979).

8th Circuit

Bradlev v. Marvland Casualtv Co-, 382

"'2d

4L5, 423 (8th

Cir. 1967 )

Miller v. Tillev, L78 F-2d 526, 528 (8th Cir' 1949)

, 720 F.2d 496, 499 (8th

ffi

r11

In re Westec CorP-r 434 F.2d I95

ffiir & Bel-,-Jc-,

r

ffi-1fT6-L-

5th Circuit

O'Learv v. Ligqet! -Prug-9o*, -159-I'2d 656, 65-7-, -9ErL.s. 273, 90 L.Ed'2d 467

7th Circuit

Schnell v. Allbriqht-Nell Co.r 348 F.2d 444, 446, gert.

s. 934, 15 L.Ed-2d 851

9th Circuit

U.S.v.Haas&HaynieCorp-,577F'2d568,578(9th

27/ Halkins v. Helms, 598 F.2d l, 8 (D.C. Cir. 1970). Since

ffie ffidum in this case reflected only tentative

conclusions of the court expressed during a status hearing,

there was no reason to susp6ct the case did not receive fu1l

and careful consideration 6y the district court. SEE=alsg:

HiII A Ranqe sgnqq, Inc, Y, FTed.Roge--Music, Inc. r 570 F.2d

558 (5th Crt.

cooper Terminal co., 2L7 ffiCir' 1954)'

28/ A11 three circuitsr ES an extrapolation of this premise,

not. it"t even though the findings may have been prepared by

counsel for the victorious party, the trial court becomes

solely responsible for theii coirection. This analysis is

implilafy iupported by the Supreme Court's holding in Pl-

Paso, srfprd, th"t "f iidings piepared in this manner, will

not Ue@cted out of hand." However, this is in error aS

[f," j"ageTattorney never stand in a (quasi) agency relation-

ship.

29/ Schwerman{r Trucki{rg Co. v. Gartlan@, EEPIS'

at L47 ' To r

"'find-ing= prepared by counsel ana adopted_verEatim Uy the trial

iudge'usirtp the function of the trial court. Nonetheless,

[f,"i" findings are considered formally his and will stand if

supported by the evidence o! r99oT9:. 99. "i:9:. Sglrnell

=v' . -eii[ii"r,i-n.ri c"., _349 I.2q-14! !7tl.E--f96s), cert. denied,

25/ Continued

5th Circuit

(5th Cir. 1970)

338 F.2d 502, 5L2

u.s. 926, 14 L.Ed.2d

ffi denied, 384 u.s. 914.

30/ See: Machlett Laboratortes, stries '

565 r.2d 7g5 tim

the prevailing party's findings of.fact and conclusions of law'

consistent wi[fr'the Fourth Ciicuit's view of this practice (to

30/ Continued

be discussed in Part B), the appellate court decided that when

the district court merely adopts wholesale, the findings and

conclusions of the prevailing party, "they may therefore be

more critically exairinedr " at 797 . The Court of Appeals in

reviewing the irial court's findings held that the district

court abrised its discretion by granting a preliminary injunc-

-

tionr partly based on the mannei in which they made their find-

ing= .

t

S." itso: Carcia v. Ru,slr;PrggbYterian-St. Luke' s Med-

ical Center, 600 f

do-rcffitomat Corp.,-996 F.Zd iO4, Z3I (7th Cir. L9791,

gL7, I0O S-Ct - L278, 63 L.Ed.2d 601'

3L/ To reiterate F.R.C.P. 52(a) unambiguously requires the

6urt to find the facts specially and state separately its

conclusions of Iaw.

32/ AI l ied Van Lines, Inc. v - Smal.lEqsiness Administration '

G,6

Courtesv Lincoln Mercury, 536 F.2d 806, 808 (8th Cir. L979).

| ?e7_ F -21

^95r, ^ 15|, -18.1-9iT:tgiglt , 439 F.2d 670, 673 (8th

cir. ig , LzL F.2d 570, 673 (ath

Cir. 1948); ermarkets, 720 F'2d 326'

336 (4th cir ses' Accgr9:

Lg46 Advisory Committee Uoie to RuIe 52(a) states that "the

judge need oify make brief, definite, pertinent findings and

6on6tusions up6n the contested matter .. .. " Unitel Etates v'

Forness, suprl; United 9!+tes v--Crescent Amusement C9:,^:EPES'

See also, groiln 337-

( 8th Cir. 1943 ) .

34/ Jones v. Intern. Paper 9o. ! 120 F.2d 496, 498 (8th Cir.

Cir. Lg82) i F;lc . CourtesY Lincoln lulercurv'

535 F.2d at citing Christensen v' Great

Plains Gas co., 418 F.2d gg5, fbOO (At[

33/ Roberts y. Ross, supra at 751.

35/ Ramev Const. Co., Inc. v. Apache Tribe, Etc., 6L6 F.2d

46q l rotrr cir. l98o ) .

36/ Id., at 466 ( lOth Cir. 1980 ) - See 31-sot- -!w?I'P.on=f

YoYPg=-,

EleIInc. v. Seaqraye. Corp. , 55I r. ?d -17I , L7 3 ( 8th Cir. L977 )

not concluding that the findings

were "Clearly erroneousr " nevertheless remanded the case to

the district court for more detailed analysis.

37/ Faulk v. Ohio Dept. of_ BgbSbilita_tio! & correction, 7-!3

F'.2d an emPloYment dis-

crimination case under Civil Rights Act of 1866'

38/ Roberts v. Rossl s.rfPrar at 75? (3d^Cir. 1965), as elab-

Eatffi eiffi-sas goard of Corrections', 505 f -2d

rga,

-irr--n

v

39/ Note to counsel: Such an argument is buttressed when the

Eiaf-c,1,1ffi-Tfndings are a wholesale adoption of the prevail-

ing party's proPosed findings-

40/ In Cross v. P+sley,267 F.2d 824 (8th Cir. 1959), the

ilghth Cffi on language from the Ninth Circuit

caie, Irish v. U.S.-, 225 F.2d 3, 8 (9th Cir. 1955), held the

findin@EEquatebecausetheyfaiIedtoaidtheappeI.

late c6urts in "a clear understanding of the basis of a trial

court's decision" and therefore remanded the case to the dis-

trict court for additional findings of fact and conclusions

of law.

4L/ Bradlev v. tlarvland casualty co. , 382 F.2d 4L5, 423 (8th

Cir. L967).

42/ United States v. Birnbach, 400 F.2d 378 (8th Cir. 1958),

e.mpha the Rule, (I) to aid the appel-

late court on review- and (2) to assist the trial judge in the

adjudicative processr ES well as the Advisory Committee notes

which cautionld that the "findings represent the judge's own

determination. See also: Swanson v. Youngdalgl !91 F.2d 171

(8rh Cir. L977)i ralcon pqffi2d 805 (8th Cir.

L976)i and Staniey .Zd 651 (gth Cir. 1979).

43/ Schlenskv v. DorseY,_ 574 F.2d at 148-49 ( 3d Cir. 1978) i

n6uerffia at 752-53 (3d cir- 1965).

Y./ See, €.Q. r Fave CgrP, ]r- -Yarcg-Illerlational, Inc' , .577IfZa 5OO, 56f 5 Amstar Corporation v.

Domini's PLzza, Inc., 615 F.2d 252, 258 (5t'h Cir. 1980); Kaspar

Lees Engineerinq, 5-15 F.2d 530, 543 (5th

, 508 F-2d \298-II . L>lOli I\J.lIlIgLU v. vqllrs€, r"v' v' -s--vw' :-- -

(5th cir' rg ' 559(5th Cir. 1978); James v. Stockhar,n varves & !'1!:Elns.90:

F.2d 3I0, 314 n. 1 (-5EE-Cir. 1977)i George W. Bennett BF.2d 3I0, 314 n. 1 (5th Cir. L977)i George W. Bennett ErYSon

& co. v. Norton Lillv a co., 502 r.2d-Ta5 (Atn Cir. L979);

nama Canal Co-, 298 F-2d 733, 737nama Canal Co-, 298 F-2d 733, 737

(5th Cir. L9621.

45/ Ramey Const. Co., Inc. v. Apache Tribe, Etc., 6L6 F'2d

4,64 , 467 ( t0th Cir. f 980 ) .

46/ International Controls Corp. v- V , 490 F.2d 1334,

TSer -,

329 F.2d 75L (2d Cir. 1964).

47/ In re Las Colinas, Inc.,

1970), cert. denied, 405 U.S.

48/ The Ninth Circuit has repeatedly cautioned the trial courts

frainst the practice of adopting one party's proposed f indings.

see: vutton Et FiIs, S. A. v. J. Lanq Enterprises, Inc., 544

F.2d i urve Contact Lenses

426 f.2d 1005, 1009 (Ist Cir.

1057, 91 S.Cr. 1002 (L972).

v1

48/ Continued

v. Rvnco Scientific Cofpr, 580 F.2d 505, 607 (9th Cir. 1982);

,- -137

coiporation v. rnt' t r,olgilr ig!,

, 651 F'2d 622

(9th Cir. 198r).

49/ Earlier Fourth Circuit cases exPressed no per se disap-^

!?oval of the use of such findings. S"9: THP SEYERANCE, 152

i.za 916 (4th cir. 1945); Chicopee Manuf+ctufiqg.coqPr v.

Kendall co., 288 F.2d 7L9,-TZE:Zr-(4th cir. 1961); white v-

ffiperboard corp. , 564 F.2d 1073 (9th cir- L977) -

50/

t982

r983

5L/

dr.

I978

52/

1970

Askew v. United States, 580 F.2d L206, L208 (8th Cir.

, 720 F.2d 496 (sth Cir'

Amstar Corp. v. Domino's Pizza, Inc., 515 F.2d 282 (5th

F.2d L264 (5th Cir'

In re Las Colinas, Inc., 426 F-2d 1005, 1010 (lst Cir.

United States v. Forness, supra at 929.

53/ Ramev Construction Co. v. Apache Tribe, 6L6 F.2d 464, 459

( 10th Cir. 1980 ) .

54/ Cuthbertsgn v. Biqqer Frgs. , 79? \.2d 454 (4th Cir. 1983);

ffioc , 698 F.2d 633, 539-41 (4th

15/ Amstar Corporation y. Domilo's Pi?za, Inc., 6r: F.2d 252,

Ba ( ,

298 F.2d .733, 738 (5th Cir. L962).

56/ Continuous Curvq 99Bta9!-L9!FPs.. Inc, -Yr. Rvnc9. Sqigntific

6rpo ir. L982); -unitgd Q!+tes

vffiaTsffiaf F.2d 1358 (9th Cir. 198I), cert. denied, 454

ffi3, 102 s.ct. 100I, 7L L.Ed.2d 294; Hagans v. Anifus,

651 F.2d 622 (9th Cir. I98l), cert. denied, 102 S.Ct. 313, 454

u.s. 859, 70 L.Ed.2d 157.

57/

58/ Inadequacy of findings

conclusoryr g€tl€rE1 f indings

363 U.S. 278, 4 L.Ed.2d 1218,

of specificity to afford the

ing of the basis of the trial

could be characterized as either

as in Commissioner v. Duberstein,

80 S. ia

reviewing court "a clear understand-

court's decision. " Allied Van

Lines, Inc. v. SmalI Business Administration, 667 F.2d 751, 753

th Cir. ee arso:

Care Centers, Inc., 7L8 F.2d 138

- v].]. -

W-/ Continued

employment discrimination case, the appellate court vacated

inE rl*"nded a trial court's decision which made only-9o!91u-

;;;y-iitaitg". e"t se*: F*,nife? v' noftreinz'61? F'2d 442

iaif, cir. rie6l, wheffin affiorandum opinion

was sufficient.under Rule 52(a) although the memo did not

""nt.i"

any aetiiled discussion of aPplicable law and did

not cite cases or statutes-

- V111