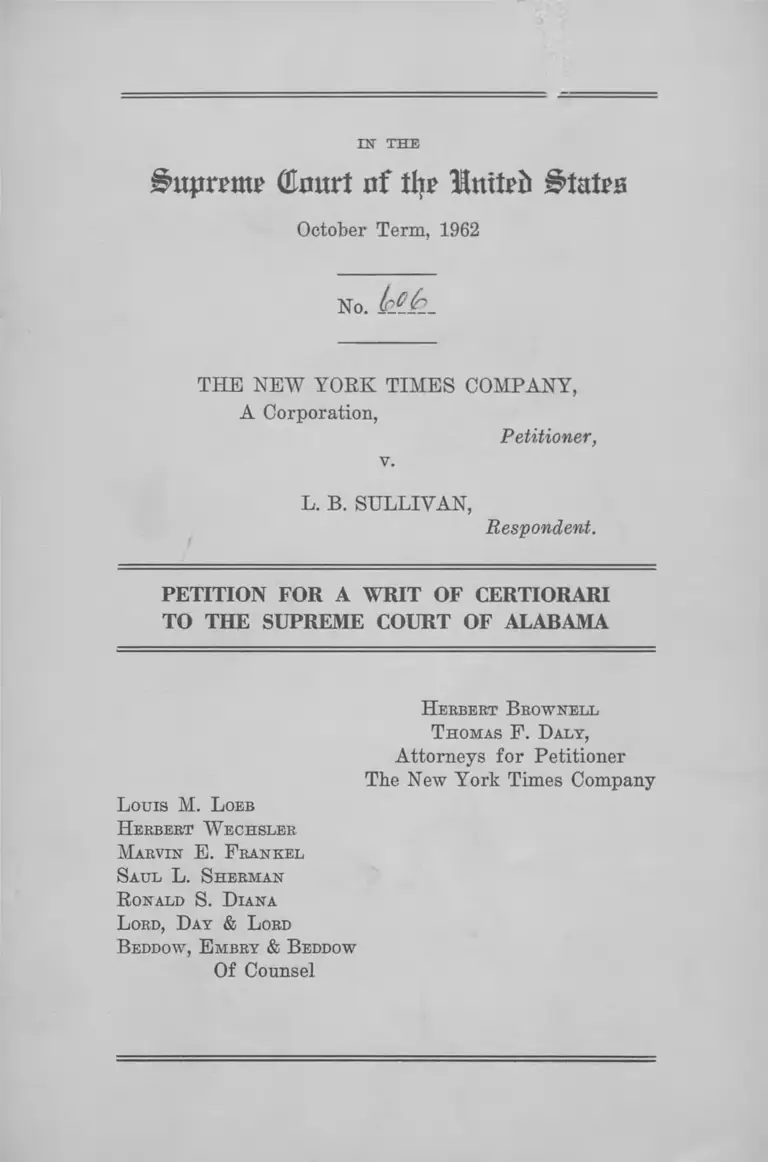

The New York Times Company v. Sullivan Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Alabama

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1962

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. The New York Times Company v. Sullivan Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Alabama, 1962. 1e10dd7c-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c3d7df08-202c-4cd8-9105-0c1bdaf6dbc7/the-new-york-times-company-v-sullivan-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-supreme-court-of-alabama. Accessed February 26, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

Supreme (Emtrt of tty llnttfb ĵ tatea

October Term, 1962

No. ( f i t .

THE NEW YORK TIMES COMPANY,

A Corporation,

v.

Petitioner,

L. B. SULLIVAN,

Respondent.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE SUPREME COURT OF ALABAMA

H erbert B rownell

T homas F . Daly,

Attorneys for Petitioner

The New York Times Company

Louis M. L oeb

H erbert W echsler

Marvin E. F rankel

Saul L. S herman

R onald S. D iana

L ord, Day & L ord

B eddow, E mbry & B eddow

Of Counsel

INDEX

Opinions B e l o w ------------------------------------------------------------ 1

Jurisdiction ------------------------------------------------------------------ 1

Questions P resen ted --------------------------------------------------- 2

Statement ____________________________________________ 3

1. The nature and circumstances of the alleged

libel ____________________________________________ 3

2. The evidence of allegedly libelous impact upon

respondent ------------------------------------------ 6

3. The demand for a retraction------ ---------— 8

4. The rulings below on the m erits____________ 8

5. The jurisdiction of the Circuit Court _ 9

R easons for Granting the W r i t -------- -------------- -------- 12

Conclusion -------------------------------------------------------------- 31

A ppendix A ___________________________________________ 33

A ppendix B ___________________________________________ 37

A ppendix C ----- 105

Citations

Cases :

Abrams v. United States, 250 U. S. 616------------------- 13

Age-Herald Publishing Co. v. Huddleston, 207 Ala.

40 ______________ 28

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U. S. 249 -------------- — ....... 21

Bates v. City of Little Bock, 361 U. S. 516___ — 20

Beauharnais v. Illinois, 343 IJ. S. 250 ______ 15

Blankenship v. Blankenship, 263 Ala. 297 ____ __ 23

Bridges v. California, 314 U. S. 252 ---------------------- 14,18

Canadian Pacific By. Co. v. Sullivan, 126 F. 2d 433

(1st Cir.) cert. den. 316 U. S. 696 ------------------------ 24

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 II. S. 296 _ 12,14, 20

PAGE

11 I N D E X

Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U. S. 568 _____ 15

Craig v. Harney, 331 U. S. 367 ____________________ 14,18

Ex Parte Cullinan, 224 Ala. 263 ----------------------------- 22

Dailey Motor Co. v. Reaves, 184 N. C. 260 _________ 23

Davis v. Farmers Co-operative Co., 262 U. S. 312 24

Davis v. O’Hara, 266 U. S. 3 1 4___________________ 23

Davis v. Wechsler, 263 U. S. 2 2 ____________________ 23

Dean Milk v. City of Madison, 340 U. S. 349 _____ 15

De Jonge v. Oregon, 299 U. S. 353 ________________ 13

Denver & R. G. W. R. Co. v. Terte, 284 IT. S. 284 __ . 24, 30

Edwards v. California, 314 U. S. 160 __ ________ 29

Erlanger Mills, Inc. v. Cohoes Fibre Mills, Inc., 239

F. 2d 502 (4th C ir .)____________________________ 30

Fisher’s Blend Station v. Tax Commission, 297

U. S. 650 ______________________________________ 30

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157________________ 18

Grosjean v. American Press Co., 297 U. S. 233 __ __ 20

Ex Parte Haisten, 227 Ala. 183___________________ 22

Hanson v. Denckla, 357 IT. S. 235 ________24, 25, 26, 27, 28

Harrub v. Hy-Trous Corporation, 249 Ala. 414 - 22

Hartman v. Time, Inc., 166 F. 2d 127 (3d Cir.) cert,

den. 338 U. S. 858 ______________________________ 26

Hutchinson v. Chase & Gilbert, 45 F. 2d 139 27

Insull v. New York World Tel. Corp., 273 F. 2d 166,

(7th Cir.) cert, denied 362 IT. S. 942 ____________ 26

International Shoe Co. v. Washington, 236 U. S.

310 ______ 24,25,26,27

Kilpatrick v. Texas & P. Ry. Co., 166 F. 2d 788 (2d

Cir.) __________________________________________ 29

Kingsley Pictures Corp. v. Regents, 360 IT. S. 684 __ 18

Konigsberg v. State Bar of California, 366 U. S. 36 14,16

Mattox v. Neivs Syndicate Co., 176 F. 2d 897 (2d

Cir.) cert. den. 334 IT. S. 838 __ _________ ___ 26

PAGE

PAGE

McGee v. International Life Ins. Co., 355 U. S. 220 _ 27

Michigan Central Railroad Company v. Mix, 278

U. S. 492 ______________________________________ 24, 30

Morgan, Connor and Waggoner v. Columbia Broad

casting System, Inc., U. S. D. C. N. D. Ala. (So.

Div.) Civil Actions No. 10067-S, 10068-S, 10069-S 19

N. A. A. C. P. v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449 20, 21, 22, 23

Near v. Minnesota, 283 U. S. 697 __ _______ _ 15

New York Times Company v. Connor, 291 F. 2d 492 19

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U. S. 587 18

Olcese v. Justice’s Court, 156 Cal. 82 23

Orange Crush Grapico Bottling Co. v. Seven-Up

Company, 128 F. Supp. 174 (N. D. Ala.) . 22

Parks and Patterson v. New York Times Company,

195 F. Snpp. 919, rev’d. September 18, 1962 19

Pennekamp v. Florida, 328 U. S. 331 14,18

Perkins v. Benguet Consol. Mining Co., 342 U. S.

437 ___________________________________________ 25

Polizzi v. Cowles Magazines, Inc. 345 U. S. 663 28

Putnam v. Triangle Publications, Inc. 245 N. C. 432 30

Roberts v. Superior Court, 30 Cal. App. 714 23

Roth v. United States, 354 U. S. 476 ____________ 15

St. Mary’s Oil Engine Co. v. Jackson Ice <& Fuel Co.,

224 Ala. 152 __________________________________ 22

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 __________________ 21

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U. S. 479 ___________________ 15, 20

Smith v. California, 361 U. S. 147 __ _. _____ 15, 20, 30

Speiser v. Randall, 357 U. S. 513 _____ ____ 20

Staub v. City of Baxley, 355 IT. S. 313_________ __ 23

Sweeney v. Patterson, 128 F. 2d 457 (D. C. Cir.

1942) cert, denied, 317 U. S. 678 (1942) 15

Sweeney v. Schenectady Union Publishing Co., 122

F. 2d 288 ____________________ _____

INDEX 111

16

IV I N D E X

Thompson v. Louisville, 362 U. S. 199 ------------------- 18

Thompson v. Wilson, 224 Ala. 299 ------------------------- 23

Times Film Corporation v. City of Chicago, 365

U. S. 4 3 _______________________________________ 14,15

Travelers Health Assn. v. Virginia, 339 U. S. 643 - 27

Ward v. Love County, 253 U. S. 1 7 ------------------------ 23

Whitney v. California, 274 U. S. 357 ---------------------- 19

Willis and Penton v. Columbia Broadcasting Sys

tem, Inc., U. S. D. C. M. D. Ala. (No Div.) Civil

Actions No. 1790-N, 1791-N_____________________ 19

Wood v. Georgia, 370 U. S. 375 ____________ __ 14,18

Zuber v. Pennsylvania R. Co., 82 F. Supp. 670 (N. D.

Ga.) __________________________________________ 24

Statutes:

Act of July 14, 1798, 1 Stat. 596 13

Title 28 U. S. C. ̂1257(3)_____________ ___ 1

Title 7 Section 199(1) Code of Alabama (1940) 3

Miscellaneous

25 ALR 2d 838 _______________________________ 23

Cliafee, Free Speech in the IJnited States

(1941), pp. 27-29 _______________________________ 13

Leflar, The Single Publication Bide, 25 Rockv

Mt. L. Rev. 263 (1953) ______________ . 26

Prosser, Interstate Publication. 51 Mich. L.

Rev. 959 (1953) ___ 26

29 Univ. of Chi. L. Rev. 569 (1962) 26

PAGE

IN TH E

Supreme Court of ttjr Mnttrb t̂atra

October Term, 1962

No.

THE NEW YORK TIMES COMPANY,

A Corporation,

v.

Petitioner,

L. B. SULLIVAN,

Respondent.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE SUPREME COURT OF ALABAMA

Petitioner respectfully prays that a writ of certiorari

issue to review the judgment of the Supreme Court of

Alabama entered in the above-entitled case on August 30,

1962.

Opinions Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Alabama (Appen

dix B, infra, pp. 37-78) is reported in 144 So. 2d 25. The

opinion of the Circuit Court, Montgomery County, denying

petitioner’s motion to quash service of process (Appendix

B, infra, pp. 80-89) is unreported. The charge to the jury

of the Circuit Court (Appendix B, infra, pp. 89-104) appears

at R. 1947-1954, 1957A-1957J.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Supreme Court of Alabama (Ap

pendix B, infra, pp. 78, 79) was entered on August 30, 1962.

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under 28 U.S.C.

§ 1257 (3).

.•H I 2 '■1

Fi'xtnt'fe i'ntiiji£say i8'*ete }A y ^ w m i f i i d

KJU-! 1 ,in i 'i p ■j‘)(Lot‘)( >

1. Whether, consistently with the guarantee of freedom

of the press in the First Amendment as embodied in the

Fourteenth, a state may hold libdtfms per se and actionable

by an elected City Commissioner, without proof of special

damage, sts^rrmpj^i critippl[(|f t̂ ip (popdiiei; p f^ j department

of the City Government under ^^..^im^dicjiion which are

inaccur^tp.jn, vsome particulars.

2. Whether there was sufficient evidence to justify, con

sistently with the gharaniee ^olffreedom of the press, the,.\ > *>V\

determination that statements, naming no individual but

critical of the Police .Department under the jurisdiction of

the reppijident;^:gin'.ieljec'tediCity Cbirtnttis&tsiefl, rtyfete de-

famat/ify/aft ,tft hiid ©niiVffulidfib aMMif 9flSbfcknri\jftr tefel

’’ 3! Whether an'award of'$oOd,'i[66‘ as “ presumed” and

‘I'd r.-HM)’ Mli j , ' Ip I l l ' H U v J m i , ' J i l l , , / / ‘ ) i ; / '>'I '■>! , • 'll ipunitive damages for libel constituted, in the circumstances

.lU. .P'.nyii A IK . •.<14-1 Jjjii ti lie-:.7<«Iku‘)iIi ii i J .•.-i-i Iilm juuki In I /.of this case, an abridgement ot the freedom of the press.

4. Whether the assumption''o¥* jurisdiction in a libel

action/-against :id foreign ’edfpora'trdii1 publishing 6L: news-

pit>er ih hnother^tktfe', isase'd upon Sporadic hewsgatherin^

activities 'by! Vof respondents, ocOaSiiWar 'sdlicitatibn b f1 ad

vertising 1 andr 1 thlhiife'ctllb/ dfetiihtitioffi 'of: 'the nowspape'f

within1 the fbf’tfiri 'stalty, tiJanS'cejilded the territorial limita

tions! <df diie d’focessj ihlposted a'forbiddeh burdbii oii ititei1-

state commerce or abridged tire ̂ frWdbih of* tli4 press.'

iioil*>ii>fei*i.ul.

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

<|/. ) m u l id u l 7 . In t - i i id > M i i i ' r i q i i A v i n l d t i i ' j ingTi iJ i . • m i

.L-iuThe!'. constitutional-: and 'Statutory . provisions involved

ar^sdt fbrthiioaiAippiendik-A,'mfrh,-p î 33-36:* t’>il ■-> : m1 i

i 7f.;;j •'

3

•«*'| .l-iren-i \y, »ilt l.iiu -.'Statemeiituit iiil/'. l*n-.‘t-*< I. ol ••mini

The 3u'dgA!i,eiitlbf(thk‘S ilpi,eiie CohiT'of Aikbhmh'i'tf’thik

ckuse kffirbifed'a'^d^fafieM'^'f'ttte1:Circuit"fburt o f'^ b fd -

^Gtne'fy CBiiritV, 'eiitdfbd1 oh thd: f di'ditit' of !h jitry1,' a^kjftikt

til'd petitioiidfh'iid fBUr 'db-dfifoiid'aii'tsV Rallpli D. Addfnkfh'y',

Ft eel L; Shkittibs’kWt'li, S’! 'SJSed^' ‘St.'j 'add "Jr 'EJ iEo\i’f lry;

k^krding 'rdU^nAdti^ $90(/,€00,"tlifei ftilF htnouhf'dlkimGd'

dkMdjged® f i t ' libdl1 "(iR.:! f9'58) f ‘ ’ Rdspbfdeiif,' onb 1 b f 1 iMred

efddted1 CBmttii'.ssiond'i ’̂ i f ! the1 'City ' o f 1 Mdntyblifeiy,11AM-

buhia1, indtifutd&>thd adtliW till 'April119,1 TfifeO'/ Afldgiri^ ‘fhbt

lib 'had been libdidd'by't'wHj 'paba^r’apK^'df ad adVd'ttisehieiit

pIkbliihed'ilh l̂ F<OA<^ YYA'lc'TMes dii’M k m

idk o f ptbbdks1 'blade1' ’dn" ‘petitioned1 'hV ddlifei-y"tb"Efd

illd^ed'h'^bftFdri'ArdbahVa' ah'ddiy'dubbtRiited1 'idrVicd pilF-

Hiiaftt'td t L 1 ”* TOiftb ofthe S tk # (Titld!7, t o

tlioh 1'99' '(l1), lib'dd1 "of 'A fdiM a,11 A f'p e f'd t 'A1, 'infrtii fr 34V.

A motion to quash asserting constitutional objection^ W th'b

^MfpA^tiop,. ,Qf , the, _ Circuit ( Cpi^rt. .under ( ̂.dye t . r̂|??eSs

clause, pf the Fourteenth Amendment and the. CommerceP.Tin - ni'ir.iKxj^ri in <i- 1;<I • >iTr >!-.// iUzi* ->111 11. Tiiar Inin

Clause (R, 33, 39,350) was denied (R. 47). In the.ensuing-ujo-i riift .jtT*irjTMKiIt »/i>i> '.fit fn iH(i!igf;ii;nf P.irf '.ill juiifn

trial, petitioner contended bv demurrer (R. 58-9). objection-innT• ft: ini '/Trin'in'ir Monrcî Mn .'fTi'ilnionx'n ■/■H'lo IthiiiMii

fa • f e , i W , , ( g ; / 1^ P f o ^ e4i,C°T„.^

directedverdict ,(R. 1957M), and motion for a,,new-trial*i> / ill in 11 > inuiniilNn 'm in i mgr* •iirTfo uoiTiairirflii •i/iti-iod

c* uldl n?,ft b9.!h^ , . t,? ,r W

the respo.p^pt w i$ p 4 ^ rk lp ;n ^ $ e ( freedom (pf the ^

guaranteed .fe.fhp ^pprteent^ Am epdm ent^.J^

contention was rejected by the Circuit Court. The Su-

pt^iiid <Cofiidtl o f Alabama lsdsta>iudd4heae; t-l*(lihgsl on appeal.

Inin .•rii vi'K -mtnrnn-ibim! iriiildo of .rurihnn’ ) iltuorl ,-g-inii

11alt . The nature and circumstances; o f the! alleged, libel

adveiltisemept (R)il698-17;Q2)ya copy- o f (which was af:

tached to the complaint (R. 2-10) and is set forthibeldWiiin

Appendix C, infra, p. 105, was placed through a New York

advertisiri^'agdhc^'by' Shi’ oFgatii2atton’!hamed;rthb -“‘ Com

4

mittee to Defend Martin Luther King and the Struggle for

Freedom in the South.” It named approximately 80 in

dividuals as officers and members of the Committee, in

cluding many of national and world fame for humanitarian

work and for achievement in religion, political affairs,

trade unions and the arts, tinder the title “ Heed Their

Rising Voices” , taken from a New York Times editorial

of March 19, 1960, the advertisement portrayed the activi

ties and struggles of students and others engaged in non

violent demonstrations against the practices of racial

segregation. As indicated by the Committee’s title, the

advertisement centered mainly on the problems of Dr.

Martin Luther King, Jr., founder and president of the

Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and concluded

with an appeal for funds to support the legal defense of

Dr. King, who had been indicted shortly before for

perjury.*

Of the advertisement’s ten paragraphs of text, the third

and part of the sixth were the basis of respondent’s libel

claim. The first paragraph of the advertisement, not com

plained of by respondent, described generally the actions

and goals of Southern Negro students demonstrating “ in

positive affirmation of the right to live in human dignity as

guaranteed by the U. S. Constitution and the Bill of

Rights.” It went on to charge that these students were

“ being met by an unprecedented wave of terror . . . . ”

The second paragraph told of a student effort in Orange

burg, South Carolina, to obtain lunch-counter service, and

reported that the students had been forcibly ejected, tear-

gassed and arrested en masse under physically trying

conditions.

* Dr. King was later acquitted on this charge (R . 1803).

5

The third paragraph, the first of the two alleged to have

libeled respondent, read as follows:

“ In Montgomery, Alabama, after students sang

‘ My Country, ’Tis of Thee’ on the State Capitol steps,

their leaders were expelled from school, and truck-

loads of police armed with shot-guns and tear-gas

ringed the Alabama State College Campus. When the

entire student body protested to state authorities by

refusing to re-register, their dining hall was padlocked

in an attempt to starve them into submission.”

Respondent’s evidence showed that the only part of this

statement thought to refer to him was the assertion that

“ truckloads of police” had “ ringed” the campus (R. 1837),

and that this assertion was incorrect “ although on three

occasions they [the police] were deployed near the campus

in large numbers” (R. 1712). It also appeared that less

than the “ entire student body” protested and that the din

ing hall was not “ padlocked” , but, as respondent testified,

these were matters relating in any event to the State Edu

cation Department, not to him (R. 1840-41).

The fourth and fifth paragraphs of the advertisement,

not claimed to be false or libelous in any respect, spoke of

student activity in “ Tallahassee, Atlanta, Nashville,

Savannah, Greensboro, Memphis, Richmond, Charlotte, and

a host of other cities in the South” ; charged hostility by

police and other officials; and went on to portray the leader

ship role of Dr. King.

The sixth paragraph began with the following sentences,

comprising the second extract charged to be libelous and

the remainder of the basis for the lower court’s charac

terization of the advertisement as “ false and malicious”

(Appendix B, infra, p. 77):

“ Again and again the Southern violators have

answered Dr. K ing’s peaceful protests with intimida-

G

•m.itumiandiYiolenico.i i They haveibombed his,bom& almost

killing his wife hav^.^^imjted,;fei?|

person. They have arrested him seven times—for

' ' 'M&l1 tbl'f dduld1 'iih^ryk’liih fdf^ew'yk^L’

........ j i v ) f l i i i i i - o m * * - I n i b . 111i / / i i ' i i i n i i ■.-m i<>«i Ktul

Ml

" ''(I)'1 ’’Mai*!l)r. Kbag‘’ahpme had’ in fact Keen bombed

twice,1 although' one . o f1 t!he ‘ bombs failed to explode,

with flf. l£ing’s" w ife ' and child at home,1'and 'that

both occasions preceded respondent’s. tenure as Com*,

'“ • v J y s w m ...............................hs.ill uni m i 1 <\\u i l l i i l <»! ! > l » i o i hidMloiH hf*.»UT‘ >h>l-

, (2) That Dr. King had been arrested .only, four..( ,!>.! ,-M)7 -!in imu-i -mTi n-Siiri , bim. •i?ffloi. to.--hiipK>l->rnTtimes, not seven as the advertisement said, three ot

1,1 !the arrests antedating respbhdehl^s ’tenure as Oommisi

*11M'dlbhef1 tK.;TT11,’ I'flB',11 8 2 7 •"ltl ' “’iH '"obiv>->o

e - ‘>l , mj,^j ''^bai!‘t);r.' ’King1 hadln ‘tact' been 'indicted on ‘two

-uibjjgJJjdi5̂ 1 diHintd,’ 1 'cht'r'jdng''-'ddteift ikl1 'sebt’diic'es "64*

fl >*>r ' ( ( R v J ̂ • i >•>/(•>«»lIn><| f(>*i < w h i ii i il ijifi

-I.I.M tt' agitate' a d ’t^W hbtM r’Dib1

King had bbbn1 'fa u lt e d 1 'db the'Wcatei'dtf b fflli 'ahheSt;

•I,, W ihrM fh*

<)lli /d>!i;/ .n lm ilt /. I “ ni / ( iv i t ’iH 111• >I>n t>

l)n The i«tfemlainder > 11 of > i iflhei i adveMisemetaty1 • >prhidingf i >DrT

wad >nofc claimed dot be' fald© or lifeelodsb-irfio'' ■'11f * * l*1" 1 •r,ib"|

.” iii /! ,i ( I to *i(,it 11iif-

2. The evidence of allegedly libelous impact upon

>■>•>!!•>tii'x miuioilot ‘Hit il Ir// iHig‘)ii ili.|I'.vii.H ii!i[ (ITzi* ‘ii! Prespondent—The condemned advertisement contained no

_ ____ ^ w ^ r e s p o n d e n t___

<1101-1, Ll lau lii.il; ' ) - ( ,; t . " - i ; f II • I I 11 ■)" i t - j ) 7 bt; •y l t . lo J i o i t a x n - i t

mony, the basis tor his role as aggrieved .plaiiijtiTX (was tip

“ feeling” that the advertisement reflected upon him, ‘ ‘ the

0 fifed Cbidhlibdioildi*^'tbid thb!cobiirinnit^1*’ fi#.'f849).

-(iliiiu itiii ii ti // <it '̂>to'!(( fnJ‘i‘>i!‘')i| <’g iiiy l .*f< 1 b'Vfov/<ffr;

7

/II' i<9pecrfitallyj1 the' eVidetite: dhowed that' 'fesponderity in his

daphcity‘as ;Commlssibnei-, had supervision’oVfeif >the;Morif

gomery Police Department, Fire Departm'eift; !J)epartment

of Cemetery and Department of Scales (R. 1827). He was

i W y ' ^ r ^ t ^ e V W W W Police

^yM^Ws^iilhludiiig 'tliak'e Mhiti^fhe' ll 'a h M a ’ Stkt'b ^bl-

le'ge11 epiifodb'1 ie f erfed1 to1 ’ ixi' the advef tii emeht \ these' he nig

dkder ’ 'the su^er^sion o f 'Montgomery hi1 th ief o f 'Police

•(RillM i r < >i1i,‘><1 f * llll(1‘ ’ •b<HM .(.I Iii<|/. m() . ( I

jio-l t tr*>! >11 < M ] >-.• II ' //nil nt y.ft l)ol.\.\II(j" 'ITI» /'lit! gll IVJi*

11' 'To establish 'thfe1 allegedly1 libelousJ effect o f1 the advertisb-

rtienf upon 1 respondeat;1'shd Witnesses and respbUderithifn-

seif were1 petihitted'Ovbf'bbjeofion to''ariaounbe'their views

that "the'1 allegedly libelous 1 'itatdhieht'S11 would'' fetid tb! be

associated 1 With1 ‘ the1 ' f ity' tjr'overhmeht,11 'with! the"1 Commis-

sibribts'gbheraUy-; • and' with • i-espoiddeht' *“ k littib i mote’ V o f

with respondent more specifically 'Und1 pUi'tlcniiarijl’ îR! l3!?2̂ ’,

1724, 1728, 1736, 1755-6, 1759, 1766-7, 1771, 1785, 1837).

Ihiree o f these wltiiesses^iaif ̂ r^ 0seenEMIi^a^yeruse'ment

when' ttiey were ‘cal’letl to 'the1 office ol ’ respondent’s! counsel

ahd’ sKdWn'it in order H,o equip lliem’as witnesses'(ill 'itfe -

40;1 T73t, iV6^-4, itte'iiy.k’ 1 ’’the" six1 witnesses' said ’thalt if

they1 hiid1 believed'1 the ' statements about ’ the" police in the

advbytisementSj ihey would have thought less ofrespondbiit,

Wdiild'1 have ' cohyidereel half1 'the' police ' had 'been guilty* !of

shribiik' hiisbehavibr and' would" have"thought respofident

wad carrying1 out the' duties of'hi4 office ihcompetentiy and

improperly (fe!T7^5, 'f tk -f f i lg h , iM f'V tjo& M lf; rf§6-7)‘

Mbwyfef,';tibne1 o f1 'the witnesses'testified that' he Relieved

the'adVertisemeht ; 'hve speciticatt'y tes'tihed 'that they dis-

>ill .•met-' 7-i•>•/•> Ik *mii;b ‘ i**;ili •g/iihvij.'dj .(()<.')L‘ .<. Xt-( L

in •>* iltrittay be'nottfi here'that iapprOiiJm!aftfclly 394fcb]iiesof the issue

the; (advertisement jp question ,y/ere circulated

in the State of Alabama; of these, approximately 35 were

to ' taoat£ottitty -Ctiurtty*(&“ *17*20) P'1< 1

distributed

Inti li ' i 'Ml

8

believed it; and none was actually led to think less kindly

of respondent because of it (R. 1743, 1745-6, 1757-9, 1764,

1768, 1772, 1789).

3. The demand for a retraction.— On April 8, 1960,

respondent wrote to petitioner and to the four individual

defendants demanding a retraction of the statements in the

advertisement which are the basis for the libel action (R.

1706-7). On April 15, 1960, counsel for petitioner replied,

saying they were “ puzzled as to how” respondent con

sidered the disputed statements to reflect upon him, assur

ing him that the assertions in the advertisement were still

being checked, and suggesting that respondent might ex

plain further to them how these assertions were deemed

reflections upon him (R. 1708). Respondent made no

further reply, but filed this suit, recovering the full $500,000

demanded by the complaint.

4. The rulings below on the merits.—As previously

noted (p. 3), petitioner contended throughout that the facts

alleged and proved could not support a judgment in

respondent’s favor for libel consistently with the freedom

of the press guaranteed by the First Amendment as made

applicable to the States by the Fourteenth Amendment.

Specifically, petitioner contended that the constitutional

safeguard was infringed by holding the publication libelous

and actionable without proof of special damage, by per

mitting and sustaining a finding that the statements were

“ of and pertaining to” respondent and in sustaining the

award of damages embodied in the verdict (R. 58-9, 2012,

2048-9, 2050). Rejecting these claims at every stage, the

trial court charged that the portions of the advertisement

in issue were “ libelous per se” , that “ [gjeneral damages

need not be alleged or proved but are presumed” , that

9

respondent was entitled to recover both, such “ presumed”

and punitive damages if the jury decided that the words

related to and concerned him and that the damages awarded

were not excessive (R. 86, 1951-4, 2057D).

In its opinion affirming the judgment, the court below

agreed with these rulings. It held that where “ the words

published tend to injure a person libeled by them in his

reputation, profession, trade or business, or charge him

with an indictable offense, or tends to bring the individual

into public contempt,” they are “ libelous per se ” ; and

that the “ matter complained of is, under the above doctrine,

libelous per se, if it was published of and concerning the

plaintiff” . Appendix B, infra, p. 53. It held, further,

that since it is “ common knowledge” that a city’s “ govern

ing body” controls such groups as police and firemen, and

since “ praise or criticism [of such employees] is usually

attached to the official in complete control of the body” , the

trial court had correctly sustained the complaint as alleging

a libel “ of and concerning” respondent and the verdict so

finding in his favor (id., pp. 55-56, 59, 77). It also rejected

petitioner’s arguments under the First and Fourteenth

Amendments (assignments of error 289-291, 296, 298, 306-

308, 310), holding that (a) these were answered by the libel

ous character of the advertisement and that (b) in any

event, the “ Fourteenth Amendment is directed against

State action and not private action.” Id., pp. 58-59.

5. The jurisdiction of the Circuit Court—Petitioner

is a New York corporation which has not qualified to do

business in Alabama or designated anyone to accept serv

ice of process there. It has no office, property or employees

resident in Alabama (R. 435-6). Its staff correspondents

do, however, visit the State as the occasion may arise for

purposes of newsgathering. In the years 1956 through

1 0

April 1960, nine correspondents made such visits, totaling,

in the view of the courts below, 153 days.* In the first

five months of 1960 there were three such visits, two by

Claude Sitton, the staff correspondent stationed in Atlanta,

and one by Harrison Salisbury (R. 117). The Times also

had an arrangement with newspapermen employed by Ala

bama journals to act as “ stringers” , paying them for

stories they sent in that were accepted at the rate of a cent

a word. The effort was to have three such stringers in the

State, including one in Montgomery (R. 122, 300) but only

two sold stories to The Times in 1960, Chadwick of South

Magazine, who was paid $155 to July 26, and McKee of the

Montgomery Advertiser, who was paid $90 for dispatches

in that time (R. I l l , 112, 297-303, 438). McKee also was

asked to investigate the facts relating to respondent’s claim

of libel, which he did (R. 180, 698).

The advertisement complained of in this action Avas pre

pared, submitted and accepted in New York, where the

newspaper is published (R. 384-386, 434). The national

daily circulation of The Times was 650,000, of which the

total sent to Alabama was 394. The Sunday circulation of

The Times was 1,300,000, of which the Alabama shipments

totaled 2,440 (R. 396-7). These papers were either mailed

to subscribers or shipped prepaid by rail or air to Alabama

news-dealers, whose orders Avere unsolicited (R. 399, 402-3,

441). The Times would credit these dealers for papers

which Avere unsold or which arrived late, damaged or incom

* The finding that “ correspondents of The Times spent 153 days in

Alabama” during these years (Appendix B, infra, pp. 38, 84) must be

based, we believe, on the petitioner’s records of the correspondents’

expense accounts, which were introduced in evidence and covered

115 days (R. 753-779) and on 50 published stories by such cor

respondents having Alabama date-lines, which were separately offered

in evidence (R . 783-1025). If so, we think it plain that the two

sets of figures involve a duplication as to dates and that the total

number of days is 115, not 153. See also R. 303-310.

1 1

plete, the latter being certified by a local baggage man upon

a form provided by The Times (R. 403, 406). Gross rev

enue from this Alabama circulation was approximately

$20,000 in the first five months of 1960 of a total circulation

revenue of $8,500,000 (R. 442).

The Times accepted advertising from Alabama sources,

principally advertising agencies which sent their copy to

New York, where any contract for its publication was made

(R. 336-8, 344-6). The New York Times Sales, Inc., a sub

sidiary corporation, also solicited advertisements in Ala

bama, though it has no office or resident employees in the

State. Four employees spent a total of 26 days in Alabama

for this purpose in 1959 and one spent one day there before

the end of May in 1960 (R. 330). Alabama advertising

linage, including that volunteered and solicited, amounted

to 5,471 in 1959 of a total of 60,000,000 published (R. 334,

336); it amounted to 13,254 through May of 1960 (R. 334)

of a total of 20,000,000 lines (R. 335). Revenue from an

Alabama supplement published in 1958 was $26,801.64 (R.

374). For the first five months of 1960 gross revenue from

Alabama advertising was $17,000 to $18,000 of a total ad

vertising revenue of $37,500,000 (R. 440). Gross revenue

from Alabama advertising and circulation during this

period was $37,300 of a national total of $46,000,000 (R.

443).

On these facts, the courts below held that petitioner was

subject to the jurisdiction of the Circuit Court in this

action, sustaining both the service of process on McKee as

a purported agent and the substituted service on the Sec

retary of State, against objections based on the territorial

limitations of due process, the Commerce Clause and the

constitutional protection of the freedom of the press (R.

33, 39, 350, Appendix B, infra, pp. 37-49, 82-88). They also

held that though petitioner had raised these questions by

1 2

motion to quash, appearing specially for that purpose as

permitted by the Alabama practice, the fact that the prayer

for relief asked for dismissal for “ lack of jurisdiction

of the subject matter” of the action, as well as want of

jurisdiction of the person of defendant, constituted a gen

eral appearance and submission to the jurisdiction of the

Court (R. 41-42, Appendix B, infra, pp. 49-52, 80-82).

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I

The decision of the Supreme Court of Alabama gives a

scope and application to the law of libel so restrictive of the

right to protest and to criticize official conduct that it

abridges the freedom of the press, as that freedom has been

defined by the decisions of this Court. It transforms the

action for defamation from a method of protecting private

reputation to a device for insulating government against

attack. I f the judgment stands, its impact will be grave—

not only upon the press but also upon those whose welfare

may depend on the ability and willingness of publications

to give voice to grievances against the agencies of govern

mental power. The issues are momentous and call urgently

for the consideration and determination of this Court.

First: The doctrine espoused by the court below is

that a public official is entitled to recover “ presumed” and

punitive damages for a publication critical of the official

conduct of a governmental agency under his general super

vision, if that publication tends to “ injure” him “ in his

reputation” or to “ bring” him “ into public contempt” as

an official—unless a jury is persuaded that it is entirely

true.

This principle of liability, resting as it does on a “ com

mon law concept of the most general and undefined nature”

(■Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296, 308), is indis

13

tinguishable in its function and effect from the proscription

of seditious libel, which the verdict of history has long

deemed inconsistent with the First Amendment. See

Holmes, J. in Abrams v. United States, 250 U. S. 616, 630;

Chafee, Free Speech in the United States (1941), pp. 27-29.

In place of fine and imprisonment as the repressive sanc

tion, damages are authorized “ not alone to punish the

wrongdoer, but as a deterrent to others similarly minded”

and the damages are fettered by “ no legal measure” of

amount (Appendix B, infra, pp. 74, 76). Such damages are

no less apt than criminal conviction to stifle that “ free

political discussion” which this Court has deemed “ the

security of the Republic, the very foundation of constitu

tional government” (De Jonge v. Oregon, 299 U. S. 353,

365).

There are, indeed, respects in which the private action

brought by the aggrieved official may be more repressive

than a prosecution for seditious libel. There is no require

ment of an indictment and the case need not be proved

beyond a reasonable doubt. It need not be shown, as the

Sedition Act required, that the defendant’s purpose was to

bring the official “ into contempt or disrepute” (Act of July

14, 1798, 1 Stat. 596); a statement adjudged libelous per se

is presumed to be “ false and malicious” , as the trial court

instructed here (R. 1952). Nor is it necessary, on the other

hand, that there be proof of injury in fact to the official’s

reputation. It is enough that if the criticism were believed,

it would “ tend” to diminish his repute with members of

the public (Appendix B, infra, pp. 61, 53).

We submit that such a rule of liability can not be recon

ciled with this Court’s rulings on the scope of freedom of

the press safeguarded by the Constitution. Those rulings

start with the assumption that one of the prime objectives

of the First Amendment is to protect the right to criticize

14

“ all public institutions’ ’ (Bridges v. California, 314 U. S.

252, 270). As Mr. Justice Roberts said in Cantwell v.

Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296, 310:

“ In the realm of religious faith, and in that of

political belief, sharp differences arise. In both fields

the tenets of one man may seem the rankest error to

his neighbor. To persuade others to his point of view,

the pleader, as we know, at times resorts to exaggera

tion, to vilification of men who have been, or are,

prominent in church or state, and even to false state

ment. But the people of this nation have ordained in

the light of history, that, in spite of the probability of

excesses and abuses, these liberties are, in the long

view, essential to enlightened opinion and right conduct

on the part of citizens of a democracy.”

Thus concern for the dignity and reputation of the bench

does not sustain the punishment as a contempt of criticism

of the judge or his decision (Bridges v. California•, supra,

at 270), though the utterance contains “ half-truths” and

“ misinformation” (Pennekamp v. Florida, 328 U. S. 331,

342, 345); there must be clear and present danger of per

version of the course of justice. See also Craig v. Harney,

331 U. S. 367, 370, 374-375; Wood v. Georgia, 370 U. S. 375.

We do not see how comparable criticism of an elected,

political official may consistently be punished as a libel on

the ground that it diminishes his reputation. The sup

position that judges are “ men of fortitude, able to thrive

in a hardy climate” (Craig v. Harney, supra, at 376) must

extend to commissioners as well.

The court below thought this submission answered by

the proposition that the “ Constitution does not protect

libelous publications” , relying on statements to that effect

made in opinions of this Court. See Konigsberg v. State

Bar of California, 366 IT. S. 36, 49; Times Film, Corporation

15

v. City of Chicago, 365 U. S. 13, 48; Roth v. United States,

354 U. S. 476, 486; Beauharnais v. Illinois, 343 U. S. 250,

266; Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U. S. 568, 572; Near

v. Minnesota, 283 U. S. 697, 715. The reliance surely is mis

placed. Except for Beauharnais, the statements merely

affirmed that the freedom of speech and press is not an

absolute; they did not signify advance approval of whatever

standards state courts might employ in the repression of

expression as a libel. And Beauharnais, while it sustained

conviction for a statement deemed to constitute a libel of

a racial group, found by the state court to be “ liable to

cause violence and disorder,” took pains to reserve this

Court’s “ authority to nullify action which encroaches on

freedom of utterance under the guise of punishing libel” ,

adding that “ discussion cannot be denied and the right, as

well as the duty, of criticism must not be stifled.” 343 U. S.

at 264.

Hence libel, like obscenity, contempt, advocacy of vio

lence, disorderly conduct or any other possibly defensible

basis for suppressing speech or publication, must be de

fined and judged by standards which are not repugnant

to the Constitution. The criterion employed below does

not survive that test because it stifles criticism of official

conduct no less potently than did seditious libel. I f there

is room for the protection of official reputation against

criticism of official conduct, despite the fact that “ public

men are, as it were, public property” (Beauharnais v.

Illinois, supra, at 263, note 18), measures less destructive

of the freedom of expression are available and adequate to

serve that end. See Edgerton, J. in Sweeney v. Patterson,

128 F. 2d 457, 458-9 (D. C. Cir. 1942), cert, denied, 317 U. S.

678 (1942). Cf. Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U. S. 479, 488; Smith

v. California, 361 U. S. 147, 155; Dean Milk v. City of

Madison, 340 U. S. 349.

16

Twenty-one years ago this Court embraced the oppor

tunity to review a decision of the Court of Appeals for the

Second Circuit which sustained, Judge Clark dissenting, the

sufficiency of a complaint alleging libel in a syndicated col

umn charging a Congressman by name with anti-Semitism

in opposing an appointment. Sweeney v. Schenectady Union

Publishing Co. 122 F. 2d 288. One of the questions pre

sented was whether the ruling involved an abridgment

of the freedom of the press. An equal division in this Court

led to affirmance of the judgment. 316 U. S. 642. The con

siderations which favored review in Sweeney are, in our

submission, more compellingly presented here.

Second: Assuming arguendo that the freedom of the

press may constitutionally be subordinated to protection of

official reputation, as it would he by the rule of law declared

below, we contend that the rule as applied to the facts of

this case infringes the federal rights of the petitioner. For

nothing in the evidence establishes the type of injury or

threat to the respondent’s reputation that might provide an

interest to which First Amendment freedom may be made

to yield. Cf. Konigsberg v. State Bar, 366 U. S. 36, 50, n. 11.

The publication did not name respondent or the Com

mission of which he is a member and plainly was not meant

as an attack on him or any other individual. Its protests

and its targets were impersonal: ‘ ‘ the police ’ ’, the ‘ ‘ state

authorities” , “ the Southern violators” . Neither respond

ent’s passion to perceive in these collective generalities

allusion to his personal identity nor the opinions of his

witnesses provided evidence sufficient to sustain a finding

that the statements were made “ of and concerning” him.

Moreover, statements which were accurate according to

respondent’s evidence surely cannot be relied on to estab

lish injury to his official or his private reputation. It is,

17

therefore, significant to note how far the undisputed evi

dence showed that the statements made were false, an exer

cise the court below cannot have deemed material, since it is

not attempted in the court’s opinion.

We have summarized the evidence above (pp. 3-8) and

we shall not repeat it in extenso here. It wrill suffice to

say that if the reference to “ the police” can validly be taken

to refer to the respondent as Commissioner with jurisdic

tion over that department, as he and his witnesses testified

and the court and jury found, the whole libel rests on two

discrepancies between the statements and the facts. Where

the advertisement said that “ truckloads” of armed police

“ ringed the Alabama State College Campus” , the fact was

that only “ large numbers” of police “ were deployed near

the campus” on three occasions, without ringing it on any.

And where the advertisement said “ They have arrested

him [Dr. King] seven times” , the fact was that he had been

arrested only four times. Three of the arrests had occurred,

moreover, before the respondent came to office some six

months before the suit was filed.

That the exaggerations or inaccuracies in these state

ments cannot rationally be regarded as tending to injure

the respondent’s reputation is, we submit, entirely clear.

None of the other statements in the paragraphs relied

on by respondent even makes a colorable case. The adver

tisement was wrong in saying that the college dining hall

was “ padlocked” but, as the respondent testified (R. 1840),

it was the State Education Department, with which he has

no connection, that had jurisdiction of this matter, not the

City Commissioners or the police. The “ Southern viola

tors” , said to “ have answered Dr. K ing’s peaceful protests

with intimidation and violence” , were not even read by the

respondent to include a reference to him (R. 1849-50). No

18

more so does the statement that “ they” bombed his home,

assaulted him and charged him with perjury point to the

respondent as the antecedent of the pronoun. And while

there was disputed evidence respecting a police assault

before respondent was elected a Commissioner (R. 1713,

1816, 1817), there was beyond dispute a bombing of King’s

home and he was charged with perjury. Indeed, to raise

funds to defend him on that charge was the main purpose

of the publication.

Since the state court’s denial of the claim that the publi

cation was protected by the Constitution turned on the

determination that it was defamatory as to the respondent,

its finding on that issue must pass muster in this Court.

There must be a sufficient basis in the evidence for the con

clusion that the statements contained falsehood injurious

to the respondent’s reputation and the nature of the

injury must justify the challenged limitation of expression.

Cf. Bridges v. California, 314 IT. S. 252, 263, 271. In passing

on these questions this Court’s duty is not only to assure

that constitutional protections are respected in the stand

ards by which judgment has been rendered but also “ to

analyze the facts in order that the appropriate enforcement

of the federal right may be assured.” Norris v. Alabama,

294 U. S. 587, 590. See also, e.g., Wood v. Georgia, 370 U. S.

375, 386; Craig v. Harney, 331 U. S. 367, 373-4; Pennekamp

v. Florida, 328 IT. S. 331, 335; Kingsley Pictures Corp. v.

Regents, 360 U. S. 684, 708 (concurring opinion); cf. Thomp

son v. Louisville, 362 U. S. 199; Garner v. Louisiana, 368

U. S'. 157.

We submit that an appraisal of this record in these

terms leaves no room for a determination that the publica

tion sued on by respondent made a statement as to him, or

that, if such a statement may be found by implication, it

injured or jeopardized his reputation in a way that forfeits

19

constitutional protection, sanctioning its punitive repres

sion by the judgment of the courts below.

Third: The magnitude of the punishment imposed on

the petitioner gives emphasis to the importance of the

questions posed by this and its companion cases in the

courts of Alabama ;* it also is, in our view, an independent

reason why the judgment has abridged the freedom of the

press.

As Mr. Justice Brandeis said, concurring in Whitney

v. California, 274 U. S. 357, 377, a “ police measure may

be unconstitutional merely because the remedy, although

effective as means of protection, is unduly harsh or op

pressive” . The proposition must apply with special force

when the “ harsh” remedy has been explicitly designed as

a deterrent to expression. It is, indeed, the underlying

basis of the principle that “ the power to regulate must be

so exercised as not, in attaining a permissible end, unduly

* Libel actions based on the publication of the advertisement here

involved, were also instituted by Governor Patterson of Alabama,

Mayor James of Montgomery, Commissioner Parks and former Com

missioner Sellers. The James case is pending on motion for new

trial after a verdict of $500,000. The Patterson, Parks and Sellers

cases, in which the damages demanded total $2,000,000, were removed

by petitioner to the District Court but the Court of Appeals for

the Fifth Circuit has held that they should be remanded. Parks and

Patterson v. New York Times Company, 195 F. Supp. 919, rev’d,

September 18, 1962. Another group of cases instituted by Birming

ham officials, based on articles on racial tensions by Harrison Salis

bury in The Times, were dismissed on jurisdictional grounds pursuant

to the decision in New York Times Company v. Connor, 291 F. 2d

492 but the Court of Appeals reversed the judgment on November

16, 1962, bowing to the Alabama Supreme Court’s interpretation of

the jurisdictional statute in the instant case and reserving constitutional

questions for decision “ upon a full record after a trial on the merits.”

Alabama officials have also filed libel actions against the Columbia

Broadcasting System based on television coverage of racial conflict in

the State. Morgan, Connor and Waggoner v. Columbia Broadcasting

System, Inc., U.S. D.C. N.D. Ala. (So. Div.) Civil Actions No.

10067-S, 10068-S, 10069-S; Willis and Penton v. Columbia Broad

casting System, Inc., U.S. D.C. M.D. Ala. (No. Div.) Civil Actions

No. 1790-N, 1791-N (pending on removal).

2 0

to infringe the protected freedom.” Cantwell v. Connecti

cut, 310 U. S. 296, 304, 308. See also, e.g., Grosjean v.

American Press Co., 297 U. S. 233; N. A. A. C. P. v. Ala

bama, 357 U. S. 449; Speiser v. Randall, 357 U. S. 513;

Smith v. California, 361 U. S. 147; Bates v. City of Little

Roch, 361 U. S. 516; Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U. S. 479.

We think this principle requires the reversal of this

judgment as oppressive, even if it otherwise could be sus

tained. Viewing the publication as an offense to respond

ent’s reputation, there was no rational relationship be

tween the gravity of the offense and the size of the penalty

imposed in his behalf. The court below declined, indeed,

to weigh the elements of truth embodied in the publication,

treating petitioner’s assertion of belief in its substantial

truth, so far as it might conceivably affect the respondent,

as evidence of malice and support for the size of the award.

Appendix B, infra, p. 77. No less important, any judg

ment of this magnitude, imposed routinely on these facts

and sustained no less routinely on appeal, will necessarily

have a repressive influence which extends far beyond pre

venting such inaccuracies of assertion as have been estab

lished here. This is not a time when it would serve the

values enshrined in the Constitution to force the press to

curtail its attention to the racial tensions of the country or

to forego dissemination of its publications in the areas

where tension is extreme. Here, too, the law of libel must

confront and be subordinated to the Constitution. The oc

casion for that confrontation is at hand.

Fourth: The court below gave as a further reason fox-

dismissing these constitutional contentions that £<[t]he

Fourteenth Amendment is directed against State action and

not private action” . Appendix B, infra, p. 59. This accepted

proposition obviously has no application to this case. The

petitioner has challenged a State rule of law applied by a

2 1

State court to render judgment carrying the full coercive

power of the State, claiming full faith and credit through

the Union solely on that ground. The rule and judgment

are, of course, State action in the classic sense of the sub

ject of the Amendment’s limitations. See N. A. A. C. P. v.

Alabama, 357 U. S. 449, 463; Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U. S.

249, 253; Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, 14.

II

In holding that the assumption of jurisdiction in this

action by the Circuit Court, based on service of process

on McKee and substituted service on the Secretary of State,

did not transcend the territorial limits of due process, im

pose a forbidden burden upon interstate commerce or

abridge the freedom of the press, the Supreme Court of

Alabama has decided federal questions of substance which

have not been and should he settled by this Court.

First: We note in limine that while the courts below

considered and rejected the asserted federal objections to

the jurisdiction, they also held that the petitioner had ap

peared generally in the action and submitted to the juris

diction of the Court. This conclusion was based upon the

ground that, while petitioner appeared specially in moving

to quash the attempted service for want of jurisdiction of

its person, as permitted by the Alabama practice, the prayer

for relief concluded with a further request for dismissal

for “ lack of jurisdiction of the subject matter of said

action.” Such a prayer, the courts held, converted the spe

cial appearance into a general appearance by operation of

the law of Alabama (R. 41-42; Appendix B, inf ra, pp. 49-52,

80-82).

The ruling lacks that “ fair or substantial support” in

prior Alabama holdings which alone suffices to defeat this

22

Court’s review. N. A. A. C. P. v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449,

455-6. The basic principle was declared thirty years ago

by the court below, in holding that a request for “ further

time to answer or demur or file other motions” did not

constitute a general appearance waiving constitutional ob

jections later made by a motion to quash. The question, it

was said, is one “ of consent or a voluntary submission to

the jurisdiction of the coui't” , an issue of “ intent as evi

denced by conduct” , as to which “ the intent and purpose

of the context as a whole must control” . E x -parte Cullinan,

224 Ala. 263, 266, 267. See also Ex parte Haisten, 227 Ala.

183, 187. Under this standard, it is plain that nothing in

petitioner’s motion disclosed an intent to invoke a ruling

as to any matter other than petitioner’s personal amena

bility to Alabama’s jurisdiction in this action.

The teaching of Ex parte Cullinan has not been quali

fied by any other holding of the court below before the

instant case. On the contrary, a motion to quash for inade

quate service has been joined with a plea in abatement

challenging the venue of the action without the suggestion

that the plea amounted to a general appearance, though the

question that it raised was characterized by the court below

as whether “ the circuit court of Talladega County had

jurisdiction of the subject matter” . St, Mary’s Oil Engine

Co. v. Jackson Ice & Fuel Co., 224 Ala. 152, 157. Indeed,

the precise equivalent of the prayer of the motion in this

case was used in Harrub v. Hy-Trous Corporation, 249 Ala.

414, 416, and posed no obstacle to the adjudication of the

issue as to jurisdiction of the person, raised on the special

appearance. See also Orange Crush Grapico Bottling Co.

v. Seven-Up Company, 128 F. Supp. 174 (N. D. Ala.) (on

removal).

Against these indicia of Alabama law, ignored in the

decisions of the courts below, the authorities that were

23

relied on are quite simply totally irrelevant. In Blanken

ship v. Blankenship, 263 Ala. 297, the court specifically

declined to consider whether the appearance had been gen

eral or special, deeming the issue immaterial upon the ques

tion there involved. In Thompson v. Wilson, 224 Ala. 299,

the defendant, a resident of Alabama, had not even pur

ported to appear specially or attempted to question the

court’s jurisdiction of his person; his sole objection, taken

by demurrer, was to the court’s competence to deal with the

subject matter of the action and to grant relief of the type

asked. The California and North Carolina cases, cited and

quoted below (Olcese v. Justice’s Court, 156 Cal. 82;

Roberts v. Superior Court, 30 Cal. App. 714; Dailey Motor

Co. v. Reaves, 184 N. C. 260) and the similar decisions

referred to in the annotation cited (25 A. L. It. 2d 838-842)

all involved situations where the defendant’s objection

raised “ the question whether considering the nature of the

cause of action asserted and the relief prayed by plaintiff,

the court had power to adjudicate concerning the subject

matter of the class of cases to which plaintiff’s claim be

longed” . Davis v. O’Hara., 266 U. S. 314, 318. That no

such question was presented here the motion makes entirely

clear.

For the foregoing reasons, we submit that the court’s

holding that petitioner made an involuntary general appear

ance does not constitute an adequate state ground, barring

consideration of the question whether Alabama has tran

scended the due process limitations on the territorial exten

sion of the process of her courts. Cf. N. A. A. C. P. v.

Alabama, supra; Staub v. City of Baxley, 355 U. S. 313;

Davis v. Wechsler, 263 U. S. 22; Ward v. Love County, 253

U. S. 17.

Moreover, even if petitioner could validly be taken to

have made a general appearance, that appearance would

not bar the claim that in assuming jurisdiction of this action

24

the state court has cast a burden upon interstate commerce

forbidden by the Commerce Clause. That point is inde

pendent of the question of the defendant’s amenability to

process, as this Court has expressly held in ruling that the

issue remains open, if presented on “ a seasonable motion” ,

notwithstanding presence of the corporation in the State

or its appearance generally in the cause. Davis v. Farmers

Co-operative Co., 262 U. S. 312; Michigan Central Railroad

Company v. Mix, 278 U. S. 492, 496. See also Denver <&

R.G.W.R. Co. v. Terte, 284 U. S. 284, 287 (attachment);

Canadian Pacific Ry. Co. v. Sullivan, 126 F. 2d 433, 437 (1st

Cir.), cert. den. 316 U. S. 696 (agent designated to accept

service); Zuber v. Pennsylvania R. Co., 82 F. Supp. 670,

674 (N. D. Ga). For the same reason, we submit, a general

appearance would not bar the litigation of petitioner’s con

tention that by taking jurisdiction in this action, the courts

below denied due process by abridging freedom of the press;

that also is an issue independent of the “ presence” of peti

tioner before the Circuit Court.

Second: The decisions of this Court do not, in our view,

support the power of the State to render judgment in

personam based on the service of process in this cause.

We recognize, of course, that there has been in recent years

a relaxation in the limitations of due process on the terri

torial authority of the state courts. But neither what this

Court in Hanson v. Denckla, 357 U. S. 235, 251 called the

“ flexible standard” of International Shoe Co. v. Washing

ton, 326 U. S. 310, nor any of its later applications, sustains,

in our submission, the determination here.

To begin, it is plain that the petitioner’s peripheral

relationship to Alabama does not involve “ continuous cor

porate operations” which are “ so substantial and of such

25

a nature as to justify suit against it on causes of action

arising from dealings entirely distinct from those ac

tivities” . International Shoe Co. v. Washington, supra,

at 318. The case bears no resemblance to Perkins v. Benguet

Consol. Mining Co., 342 U. S. 437, where the central base

of operations of the corporation, including its top manage

ment, was in the state where suit was brought. Hence, if

the jurisdiction is sustained, it must be on the ground that

the liability asserted was so “ connected with” petitioner’s

“ activities within the state” as to “ make it reasonable in

the context of our federal system of government, to require

the corporation to defend the particular suit which is

brought there.” International Shoe Co. v. Washington,

supra, at 319, 317.

No such connection has been shown. Here, as in Hanson

v. Denckla, supra, at 252, the “ suit cannot be said to be

one to enforce an obligation that arose from a privilege

the defendant exercised in” the State. The liability alleged

by the respondent certainly does not arise from the activities

of correspondents of The Times in covering the news in

Alabama; and such reporting surely does not rest upon a

privilege the State confers, but on a right, importing a

high moral duty, conferred by the Constitution of the

Nation. Nor is this liability connected with the occasional

solicitation of advertisements in Alabama; the advertise

ment in suit was not solicited and did not reach The Times

from anyone within the State. There remains, therefore,

only the negligible circulation of The Times in Alabama to

relate this action to the exercise by the petitioner of “ the

privilege of conducting activities within” the State. Inter

national Shoe Co. v. Washington, supra, at 319.

We contend that this circulation was not the exercise

of such a privilege, since it was not effected by activity of

26

the petitioner in Alabama. Copies of the paper were

mailed to subscribers from New York or shipped from

there to dealers who were purchasers, not agents of The

Times. On these facts there is, of course, a question

whether Alabama, as a matter of the choice-of-law, may

impose liability on the petitioner for causing or contribut

ing to the dissemination of those papers in the State, treat

ing it pro tanto as an Alabama “ publication” .* That

question is, however, wholly different from the issue here

presented: whether shipment of the papers from New York

involved the exercise by the petitioner of any privilege to

act in Alabama. Hanson v. Denckla {supra, at 253) is

explicit that a State may justifiably apply its law to a

transaction upon grounds quite insufficient to establish

“ personal jurisdiction over a non-resident defendant” .

See also International Shoe Co. v. Washington, supra, at

318. It “ is essential” for such jurisdiction “ that there

be some act by which the defendant purposefully avails

itself of the privilege of conducting activities within the

forum State, thus invoking the benefits and protections of

its laws.” Hanson v. Denckla, supra, at 253. Shipment in

and from New York was not, in our submission, such an

act. Nor was the judgment based, in any case, merely upon

the 394 copies comprising the Alabama circulation of

* Courts have been no less perplexed than commentators by the

conflicts problems incident to multi-state dissemination of an alleged

libel; and some have sought to solve them by a “ single publication”

rule, fixing the time and place of the entire publication when and

where the first and primary dissemination has occurred. See, e.g.,

Hartman v. Time, Inc., 166 F. 2d 127 (3d Cir.), cert, denied 338

U. S. 858; Insull v. New York World Tel. Corp., 273 F. 2d 166, 171

(7th Cir.), cert, denied 362 U. S. 942; cf. Mattox v. News Syndicate

Co., 176 F. 2d 897, 900, 904-05 (2d Cir.), cert. denied_ 334 U. S.

838. See also, e.g., Prosser, Interstate Publication, 51 Mich. L. Rev.

959 (1953) ; Leflar, The Single Publication Rule, 25 Rocky Mt. L.

Rev. 263 (1953) ; Note, 29 U. of Chi. L. Rev. 569 (1962).

27

The Times; the entire circulation of 650,000 was regarded

as relevant to the verdict (R. 1720) and offered as a reason

for sustaining the award. Appendix B, infra, pp. 75, 77.

In rejecting these arguments against the jurisdiction,

the court below relied especially on the decision in McGee

v. International Life Ins. Co., 355 U. S. 220, where suit on

an insurance contract was sustained in California against

a non-resident insurer, based on the solicitation and the con

summation of the contract in the State by mail. The con

tract was, however, a continuing relationship between the

insurer and the insured within the State and one which

the states traditionally have considered to require special

regulation. See Hanson v. Denchla, supra, at 252; Travelers

Health Assn. v. Virginia, 339 U. S. 643. No such continuing

relationship gives rise to the liability asserted here; and

newspaper publication certainly is not exceptionally subject

to state regulation.

Moreover, even if the shipment of The Times to Alabama

is regarded as an act of the petitioner within that State,

we do not think the jurisdiction here affirmed can be sus

tained. In International Shoe this Court made clear that

the new standard there laid down was not “ simply mechan

ical or quantitative” and that its application “ must depend

rather upon the quality and nature of the activity in rela

tion to the fair and orderly administration of the laws

which it was the purpose of the due process clause to in

sure” (326 U. S. at 319). See also Hanson v. Denchla, supra,

at 253. The opinion left no doubt that, as Judge Learned

Hand had previously pointed out (Hutchinson v. Chase &

Gilbert, 45 F. 2d 139, 141), an “ ‘ estimate of the inconven

iences’ which would result to the corporation from a trial

away from its ‘ home’ or principal place of business is rele-

28

vant in this connection” (326 U. S. at 317). Measured

by this standard, a principle which would require, in effect,

that almost every newspaper defend a libel suit in almost

any jurisdiction of the country, however trivial its circu

lation there may be, would not further the “ fair and orderly

administration of the laws” . The special “ inconvenience”

of the foreign publisher in libel actions brought in a com

munity with which its ties are tenuous need not be elabo

rated. It was perspicuously noted by the court below in a

landmark decision more than forty years ago, confining

venue to the county where the newspaper is “ primarily

published” . Age-Herald Publishing Co. v. Huddleston, 207

Ala. 40, 45. This record surely makes the “ inconvenience”

clear.

A different question might be posed if it were shown

that the petitioner had engaged in activities of substance

in the forum state, designed to build its circulation there.

Cf. Mr. Justice Black, dissenting in part in Polizzi v. Coivles

Magazines, Inc., 345 U. S. 663, 667, 670. That would, at

least, involve a possible analogy to other situations where

a foreign enterprise attempts the exploitation of the forum

as a market and the cause of action is connected with such

effort (Hanson v. Denchla, supra, at 251-2), though there

are differences as well as similarities that must be weighed.

It also would confine the possibilities of litigation to those

areas in which the publisher has had the opportunity to

build some local standing with the public. It is enough to

say that such activities, effort and opportunity are not

presented here.

A federated nation could not long endure unless the

power of the States to exert jurisdiction over men and

institutions not within their borders were subjected to

29

reciprocal restraints on each in the interest of all. Cf.

Learned Hand, J. in Kilpatrick v. Texas & P. Ry. Co., 166

F. 2d 788, 791-2 (2d Cir.). The need for those restraints

is clear, since when state jurisdiction does obtain, the Con

stitution obligates all other states to give full faith and

credit to the judgment rendered, including those which may

provide the only forum where the judgment can in practice,

be enforced. Thus jurisdictional delineations must be based

on grounds that command general assent throughout the

Union; were they not, full faith and credit would become

a burden that the system could not bear.

Whether these demands of our federalism have been

met by this decision is, we submit, an issue of great im

portance which calls for the judgment of this Court.

Third: In forcing petitioner to its defense in Alabama

on this cause, the courts below have cast a burden upon

interstate commerce which the Commerce Clause forbids.

The reasons are no different from those previously

stated in contending that the court’s assumption of juris

diction in personam worked a deprivation of due process.

It takes no gift of prophecy to know that if minuscule state

circulation of a paper published in another state suffices to

establish jurisdiction of a suit for libel, threatening the

type of judgment rendered here, such distribution inter

state cannot continue. So, too, if the movement of corre

spondents inter-state provides a factor tending to sustain

such jurisdiction, as the court below declared, a strong

barrier to such movement has been erected. Cf. Edwards

v. California, 314 U. S. 160. These, like other burdens upon

commerce, must be carried only when there is fair basis

for their imposition to protect a local interest that the State

may validly prefer to guard. But if, as we have urged, it

30

was not “ reasonable in the context of our federal system

of government” to require that petitioner defend this suit

in Alabama, it follows that fair basis for the burden upon

commerce has not been established. That inter-state com

munication is a form of commerce is, of course, accepted

(see, e.g., Fisher’s Blend Station v. Tax Commission, 297

U. S. 650, 654-5); and that state judicial jurisdiction may

impose a forbidden burden also is entirely clear. See, e.g.,

Michigan Central Railroad Company v. Mix, 278 U. S. 492;

Denver & R.G.W. R. Co. v. Terte, 284 U. S. 284; Erlanger

Mills, Inc., v. Cohoes Fibre Mills, Inc., 239 F. 2d 502 (4th

Cir.).

Fourth: We have argued that the jurisdictional deter

mination violates the Constitution, judged by standards

that apply to enterprise in general under the constitutional

provisions limiting state power in the interest of our

federalism as a whole. Even if we are wrong in these

submissions, we contend that the decision on this issue calls

for re-examination and reversal because it abridges the

protected freedom of the press.

That state action which otherwise would be defensible

may contravene the First Amendment as embodied in the

Fourteenth when it has “ the collateral effect of inhibiting

the freedom of expression” , was expressly held in Smith v.

California, 361 U. S. 147, 151. See also pp. 19-20, supra.

Such collateral effect on wliat is published and distributed

throughout the Nation is plainly presented here, as we

have previously shown.

Fifth: The decision below on the jurisdictional issue

is in clear conflict with that of the Supreme Court of North

Carolina in Putnam v. Triangle Publications, Inc., 245 N.C.

432. This, in itself, is a substantial reason for review.

31

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, it is respectfully submitted

that this petition for a writ of certiorari should be granted.

Louis M. L oeb

H erbert W echsler

Marvin E. F ranker

Saul L. S herman

R onald S. D iana

H erbert B rownell

T homas F. D aly

Attorneys for Petitioner

The New York Times Company

L obd, Day & L ord

B eddow, E mbry & Beddow

Of Counsel

APPENDIX A

33

APPENDIX A

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

CONSTITUTION OF THE UNITED STATES

A rticle I, S ection 8 :

The Congress shall have power # * *

To regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among

the several States * * *.

* * * * *

A mendment I

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment

of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or

abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the

right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition

the Government for a redress of grievances.

* * * * *

A mendment XIV

Section 1. All persons born or naturalized in the

United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are

citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they

reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall

abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the

United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of

life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor

deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal pro

tection of the laws.

ALABAMA CODE OF 1940 TITLE 7

§ 188. How corporation served.—When an action at law

is against a corporation the summons may be executed by

the delivery of a copy of the summons and complaint to the

president, or other head thereof, secretary, cashier, station

agent or any other agent thereof. The return of the officer

executing the summons that the person to whom delivered is

34

the agent of the corporation shall be prima facie evidence of

such fact and authorize judgment by default or otherwise

without further proof of such agency and this fact need not

he recited in the judgment entry. (1915, p. 607.)

# # # * #

§ 199 (1). Service on non-resident doing business or per

forming work or service in state.—Any non-resident person,

firm, partnership, general or limited, or any corporation not

qualified under the Constitution and laws of this state as

to doing business herein, who shall do any business or per

form any character of work or service in this state shall, by

the doing of such business or the performing of such work,

or services, be deemed to have appointed the secretary of

state, or his successor or successors in office, to be the true

and lawful attorney or agent of such non-resident, upon

whom process may be served [in any action accrued or ac

cruing from the doing of such business, or the performing

of such work, or service, or as an incident thereto by any

such non-resident, or his, its or their agent, servant or em

ployee.]* Service of such process shall be made by serving-

three copies of the process on the said secretary of state,

and such service shall be sufficient service upon the said

non-resident of the state of Alabama, provided that notice

of such service and a copy of the process are forthwith sent

by registered mail by the secretary of the state to the de

fendant at his last known address, which shall be stated in

the affidavit of the plaintiff or complainant hereinafter

mentioned, marked “ Deliver to Addressee Only” and

“ Return Receipt Requested” , and provided further that

such return receipt shall be received by the secretary of

state purporting to have been signed by said non-resident,

* Following the decision in New York Times Company v. Conner

291 F. 2d 492 (5th Cir. 1962) the statute was amended by substitut

ing the following language for the bracketed portion: [in any action

accrued, accruing, or resulting from the doing of such business, or the

performing of such work or service, or relating to or on an incident

thereof, by any such non-resident, or his, its or their agent, servant

or employee. And such service shall be valid whether or not the acts

done in Alabama shall of and within themselves constitute a complete

cause of action.] The amendment applied “ only to causes of action

arising after the date of the enactment” and therefore has no bearing

on this case.

35

or the secretary of state shall be advised by the postal

authority that delivery of said registered mail was refused

by said non-resident; and the date on which the secretary

of state receives said return receipt, or advice by the postal

authority that delivery of said registered mail was refused,

shall be treated and considered as the date of service of

process on said non-resident. The secretary of state shall

make an affidavit as to the service of said process on him,

and as to his mailing a copy of the same and notice of such

service to the non-resident, and as to the receipt of said

return receipt, or advice of the refusal of said registered

mail, and the respective dates thereof, and shall attach said

affidavit, return receipt, or advice from the postal authority,

to a copy of the process and shall return the same to the

clerk or register who issued the same, and all of the same

shall be filed in the cause by the clerk or register. The party

to a cause filed or pending, or his agent or attorney, desir

ing to obtain service upon a non-resident under the pro

visions of this section shall make and file in the cause, an

affidavit stating facts showing that this section is applicable,

and stating the residence and last known post-office address

of the non-resident, and the clerk or register of the court in

which the action is filed shall attach a copy of the affidavit

to the writ or process, and a copy of the affidavit to each

copy of the writ or process, and forward the original writ

or process and three copies thereof to the sheriff of Mont

gomery county for service on the secretary of state and it

shall be the duty of the sheriff to serve the same on the

secretary of state and to make due return of such service.

The court in which the cause is pending may order such

continuance of the cause as may be necessary to afford the

defendant or defendants reasonable opportunity to make

defense. Any person who was a resident of this state at the

time of the doing of business, or performing work or service

in this state, but who is a non-resident at the time of the

pendency of a cause involving the doing of said business or

performance of said work or service, and any corporation

which was qualified to do business in this state at the time

of doing business herein and which is not qualified at the

time of the pendency of a cause involving the doing of such

36

business, shall be deemed a non-resident within the meaning

of this section, and service of process under such circum

stances may be had as herein provided.

The secretary of state of the state of Alabama, or his

successor in office, may give such non-resident defendant

notice of such service upon the secretary of state of the

state of Alabama in lieu of the notice of service hereinabove

provided to be given, by registered mail, in the following