Attorney Notes on State Defendants' Petition for Rehearing En Banc

Working File

January 1, 1972

18 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Working Files. Attorney Notes on State Defendants' Petition for Rehearing En Banc, 1972. ca11d381-54e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c4f47994-eda4-41a7-9cc9-a787d0a3973d/attorney-notes-on-state-defendants-petition-for-rehearing-en-banc. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

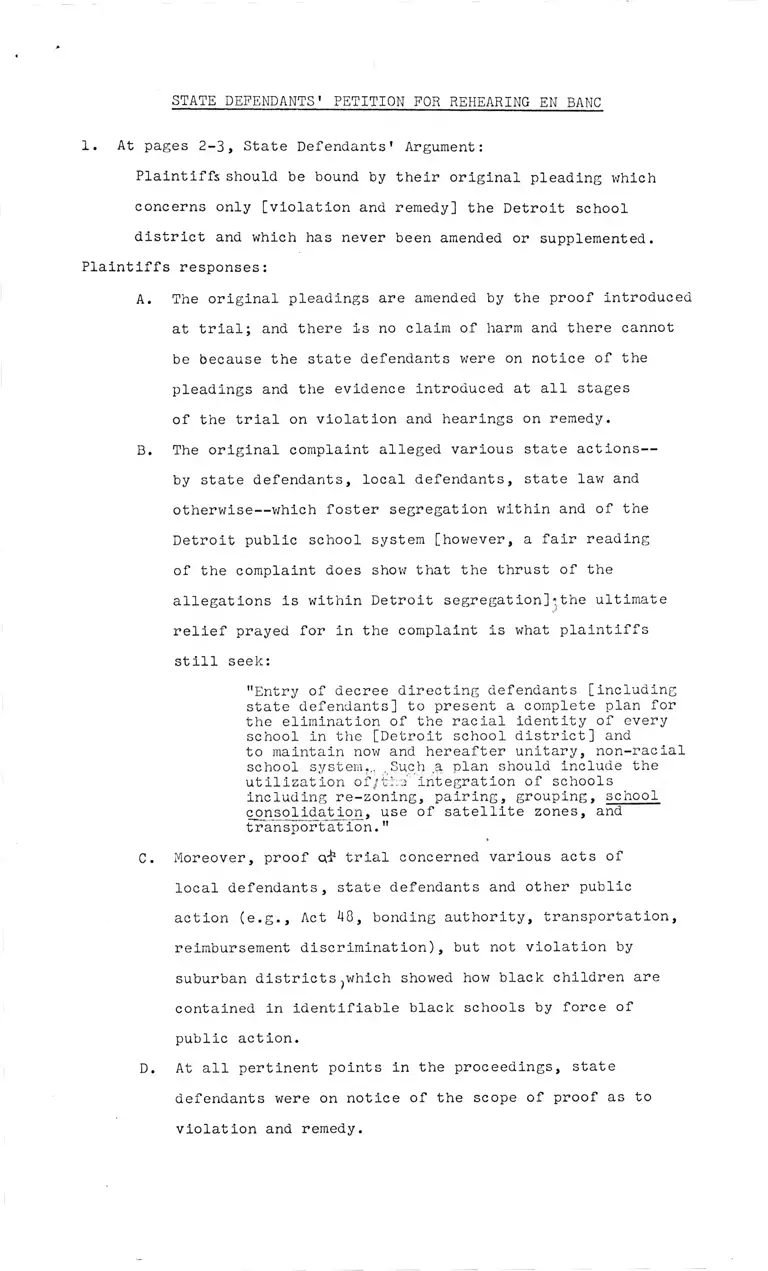

STATE DEFENDANTS * PETITION FOR REHEARING EN BANC

1. At pages 2-3, State Defendants’ Argument:

Plaintiffs should be bound by their original pleading which

concerns only [violation and remedy] the Detroit school

district and which has never been amended or supplemented.

Plaintiffs responses:

A. The original pleadings are amended by the proof introduced

at trial; and there is no claim of harm and there cannot

be because the state defendants were on notice of the

pleadings and the evidence introduced at all stages

of the trial on violation and hearings on remedy.

B. The original complaint alleged various state actions—

by state defendants, local defendants, state lav; and

otherwise— which foster segregation within and of the

Detroit public school system [however, a fair reading

of the complaint does show that the thrust of the

allegations is within Detroit segregation]'the ultimate

relief prayed for in the complaint is what plaintiffs

still seek:

"Entry of decree directing defendants [including

state defendants] to present a complete plan for

the elimination of the racial identity of every

school in the [Detroit school district] and

to maintain now and hereafter unitary, non-racial

school system.,. .Such a plan should include the

utilization of;the integration of schools

including re-zoning, pairing, grouping, school

consolidation, use of satellite zones, and

transportat ion."

C. Moreover, proof cd1 trial concerned various acts of

local defendants, state defendants and other public

action (e.g., Act 48, bonding authority, transportation,

reimbursement discrimination), but not violation by

suburban districts?which showed how black children are

contained in identifiable black schools by force of

public action.

D. At all pertinent points in the proceedings, state

defendants were on notice of the scope of proof as to

violation and remedy.

The trial Court and panel considered the matter as a suit

against the state [under a theory of vicarious liability];

and the state rnay not be sued without its consent in

Federal Court under such a theory of vicarious liability

of the state or state officials.

Plaintiffs' responses: .

A. This is a suit against named state and local defendants;

and the judgment of the trial court runs against and

binds, pursuant to Rule 65, F.R.Civ.P., only those

named parties, their agents, successors, etc.

B. Therefore, the suit is not against the state, but

follows the 14th Amendment pleading practice approved

since ex parte Young. (See e.g., Sterling v. Constantin,

Griffin v. Prince Edward County).

C. Proof of wrong-doing, however, may go against state

actions which were not instituted by named defendants.

For example, (1) the acts of their predecessors in

office, (2) the public acts of the State of Michigan

which discriminated along school district lines and,

racially identified schools, and contributed to

segregation of schools within the city and throughout

Metropolitan area. State defendants surely would

not argue that local school board’s cannot be required

to desegregate schools which were segregated by

reason of state laws. Similarly, state defendants have

no basis for arguing that they are not similarly

"vicariously liable." This is merely a result of

the ex_ parte Young fiction to enforce the lAth Amendment;

that is, the named defendants can be required to

take all actions within their power, including their

residual constitutional duties, to provide relief for

. plaintiffs whose rights have been violated by any

state action. In this cause, there can be no

question but that the state actions complained of}

concerning actions by state and local school authorities,

2. At p. 3, State Defendants' Argument:

0 I ' A ,aneractions directly affecting, and setting the framework

for, the system of public education in the state.

^ frorD. There is no ambiguity and no fte±r\ in the District

Court or the Sirr?l\ ruling that the state .actitf̂ jr

through its officers or agents, acted unconstitutionally

to create, maintain, validate6s. augment school segre

gation in the Detroit area.

E. Proof of segregative acts in a school case may go

what .

beyond/ the particular named defendants did, (1) to

show causation and relative responsibility, (2) to

rebut the claimed defenses (i.e., -wheoe /patterns over

which school authorities had no control), and (3) to

show public acts of the State of Michigan which

contributed causally to the segregation and/or

racial identification of schools. As noted, however,

the judgment ..pursuant to Rule 65. runs only against

those who are parties, etc.

Neither the Trial Court nor the panel made any specific

findings of misconduct against the Governor and the

Attorney General as indeed on the record they could not;

also, no findings were made that they were necessary

parties for relief. [At p. 6, state defendants also point

out that there is no support for the panel's statement

that the Governor and state superintendent helped to

merge the Carver School district; and moreover, the

consolidation of the Carver School district led to a "unitary

school system" for the Carver children.]

Plaintiffs' responses:

A. With respect to the Carver School district the panel,

at page 62 copied from the Detroit Board's Brief on

Appeal which stated that the Governor and Attorney

General helped to merge the Carver School district.

I have found no proof in the record or in anything

else other than the Detroit Board's assertion to

support this statement. However, at page 71 of

the state defendants-appellee's original brief,

state defendants asserted that the Michigan Attorney

General "issued two opinions which helped facilitate

the attachment of the Carver School district...to the

Oak Park School district." Op. Att'y Gen. Nos. 357,

356-8. Whatever the truth as to the role of the Governor

and superintendent of public instruction, we do know

that the Governor is an ex officio member of the

State Board of Education and that the State Superintendent

and the Board oversee these types of re-organizations,

property transfers, annexations, etc. The facts of

Carver school incident which are supported in the

record are as follows:

1. At least through 1959, high school students in

. the Carver school district were assigned and

transported to the -clu"black Northern High

School in the City of Detroit past or away from

white schools both in the City of Detroit and

At p. 5, State Defendants' Argument:

in the immediate suburbs. The state defendants

have responsibility for all aspects of overseeing

transportation including routing, and are, therefor

fully implicated in this violation which identified

the schools in the Carver school district as

black schools, schools in the immediate contiguous

suburbs as white schools, schools and Northern

High School and perhaps, by implication, the

entire Detroit school district, as black. (IIA 193

Boundary Guide, IXA 556, 557, P.X. 185, P.M. 14,

and XA 8-9, 33-39, Drachler Deposition). After

the merger of the Carver school district with Oak

Park, (and I believe Ferndale although I am not

sure), the two historically all-black elementary

schools in this district, the U.S. Grant Elementary

and Carver Elementary, remained virtually

all-black while the rest of the elementary schools

in the two suburban school districts, Ferndale

and Oak Park, remained virtually all-x^hite.

The Governor is an ex officio member of the State

Board of Education and therefore is implicated in any

violation attributable to the state Board of Education.

Moreover, the Governor signed Act 48 with all its

constitutional infirmities and appointed the Boundary

Commission which carved out the regional districts

which the proof showed at trial and were found by the

District Court, to validate and magnify school

segregation. The Attorney General reviews "property

transfers" by his own admission, gave opinions on

the Carver district, has given opinions on the State

Board of Education's power to withhold funds for

illegal actions by the school board and generally

is responsible for enforcing the laws of the state,

including the state and federal constitutional

guarantees against racial discrimination with respect

to all state action. The Governor and Attorney General

are chief legal officers of the state with full

complement of powers associated with these ancient

offices; these powers extend generally and specifically

to statutes and control!? of acts whose actual

effects are the subject of this litigation. The

Attorney General, the State Treasurer and the State

Superintendent of Instruction, make up the municipal

finance commission xvhich has responsibility for

overseeing the bonding and debts incurred by local

school districts, and are, therefore, implicated in

the "state violations."

Thus, it is clear that the Governor and Attorney

General are proper parties for relief (although they

may not be indispensable). The judgment of the

District Court can bind them to assist in the planning

and implementation functions over which they have

considerable knowledge, expertise, and power. Indeed,

I don't see any reason why specific findings of their

wrong-doing must be made for the judgment to be binding

against them and for the Court to have jurisdiction

over them to require them to take all action necessary

to implement plaintiffs' constitutional rights.

At pp. 6-8, State Defendants argue that only three specific

acts were alleged against the state superintendent and state

board. [The 1966 policy joint policy statement, the 1970 School

Planning Handbook and the failure of the state superintendent

to use the power of site selection that he had prior to 1962

(and in particular, that the incident of site selection

relied upon by the panel refer to incidents after 1962)].

Plaintiffs' responses: .

A. Generally, see Plaintiffs' Responses IB, 1-6 to the Grosse

Pointe Petition, supra.

B. Any confusion in either opinion as to whether it is the

state board or state superintendent as to who has respon

sibility for any acts is both understanable and excusable.

For by M.S.A. 1023 (1*0, MCLA 388.10S4, the State of

Michigan by public act stated that after June 30, 1965

a reference in any law to the powers and duties of the

Superintendent of Public Instruction is deemed to be

made to the State Board of Education unless the law

names the superintendent as a member of another Governmental

agency or provides for an appeal to the State Board of

Education from a decision of the State Superintendent.

C. Act 48 gave the State Board authority over drawing

regional districts in the future. The State Board of

Education and its chief executive officer of State Public

!Instruction have general responsibility and supervision

over all aspects of education in the State of Michigan,

including power of accreditation of schools (apparently

never exercised)} regulation of school bus transportation,

review of the .x ..-attachment of non-operating

school districts, the hearing of appeals from decision

of alteration of boundary of school districts, distribution

of state aid, prior to 1962^ approval of all sites for

new construction or additions (power vested in the

-f-'V q -v '?■? v-*State Superintendent),/approval of all school construction

and re-modeling plans (albeit related to health, safety,

and fire hazards), etc.

D. The 1966 and 1970 statements with respect to the impor

tance of school construction to school segregation clearly

show the state defendants' knowledge of factors which

lead to segregation; and their failure, in the face of

such knowledge, to control these factors so as to avoid

segregation is a de jure act of pervasive

on the facts of this case throughout Detroit and the

Metropolitan area. Some of the obvious methods by

which the State defendants could have controlled this

school construction violation is by the withholding

of state monies (see panel's opinion at 64); instead, the

state defendants prior to 1962 directly approved every

site, and thereafter supported such school construction

and the operation of the newly constructed schools by

the distribution of substantial state aid, approval of

construction plans, approval of the cirriculum, etc., used

in the racially identifiable schools.

E. Much of the construction violation did occur prior to

1962. See IVA 109-112; from 1946-1959, most new school

construction followed the master plans for schools and

as noted by the 1958 Citizens Advisory Committee on School

Needs, there were 175 new buildings or additions sufficient

to accommodate 69,000 pupils built principally in the

outlying city to accommodate the white out migration.

This new school construction corresponds closely to the

increased enrollment in the city during this period,

especially the white suburban flight within the city of

Detroit to the northeast and northwest. IVA 114, DXNN,

and PX 79 show that many schools were sited and authorized

and/or actually built prior to 1962; school construction

from i960 on(including massive construction even through

the hearing of the cause,was primarily on a virtually

all-white and all-black bases „(P.X. 79 and P.X. 152 show how

these new schools were also racially identified by the

initial assignment of faculty on a racial basis as well).

Thus, it is clear; as the District Court held and the

panel properly noted, although the state defendants may

have had some racially non-discriminative policijc, their

actions were both racially discriminatory and contributed

<s<2AreAfrH.? hsubstantially to the pattern of throughout

the metropolitan area.

Factually, the bonding discrimination existed only from

1969 through 1972; and,in any event, the bonding limitations

were not imposed for the purposes of segregation nor did

they have the effect of creating or aggravating segregation.

Plaintiffs' responses:

A. See Plaintiffs' Responses IB-5 to the Grosse Pointe

At page 9, State Defendants’ Argument:

Petition.

6. At page 10, State Defendants’ Argument:

t /••>«-VU > • ; f > v . i- - i x ' f ' ' rv ’>.. ■* " ■ ' 1 . •!factually,/the record is barren that any suburban

district in the metropolitan area is a

grandfather beneficiary; and there is no evidence in

the record to show that the statutory distinction was

for the purpose of segregation or that it created or

aggravated segregation.

Plaintiffs' responses: •

A. See Plaintiffs’ Response 1B2 to the Grosse Pointe

Petition. In particular, both of state defendants'

arguments with respect to the transportation funds

discrimination are factually incorrect according

to the record made in this case.

Assuming arguendo what the panel is saying is true

relative to bonding, financing, construction and transportation,

the Carver School district, and even P.A. 48, none of

7. At page 10, State Defendants’ Argument:

these actions had the effect of creating and

segregation along school district lines.

maintaining

Plaintiffs’ responses:

A. See Plaintiffs’ Res-ponse, 1B2-6 to Grosse Pointe Petition.

In any event, with the exception of Porter' s

testimony as to transportation, all the other proofs were

admitted into evidence after state defendants made motion

to dismiss and rested.

Plaintiff's responses:

A. State defendants' view of Rule 4l (B) is ludicrous.

Their argument is that any proof introduced after

they have chosen to absent themselves from the

proceedings is not binding. As a factual matter,

defendants have returned to these proceedings ever

since September 27; so'their very factual premise

which triggers their asserted shield from evidence has

been waived by the state defendants themselves. As

another factual matter, the proof of transportation

discrimination, all the implications of Act 48,

the general aspects of the bonding and other financial

limitations, the state implications in the segregative

school construction, and the state's involvement in the

Carver school district were all of record before they

absented themselves. Surely, therefore, the District

Court was authorized to deny the defendants' motions

to dismiss, as he did, on June 25, 1971 by specific order

and as he had done prior thereto 'by notification to

defendants to be ready to assist in preparing all

possible remedies. (See AIA 152 and IV A 259-261

June 24, 1971). Therefore, state defendants were on

actual notice, prior to the completion of the

Detroit Board's own defense, of the probable outcome

of the case and their need to put in rebuttal proof.

Defendants, by intentionally absenting themselves

from the hearings, therefore, are in no position to

. argue that the District Court should thereby be disabled

from fact finding on/basis of the entire record.

8. At pages 10 and 11, State Defendants' Argument:

Plaintiffs tried their case on the theory that the Detroit

Public Schools was a segregated school district and without

reference to any other school district. Yet, based upon one

factual finding— that the Detroit School district is

predominantly black— and without giving any of the

-Turnip •allegedly discriminating school districts the «ip&$gar\to be

heard, the Court ordered metro under a theory of vicarious

liability.

Plaintiffs' responses:

A. See the theories on which the case was tried. Plaintiffs

responses 1^ 2B^ 1-5 to the Grosse Pointe Petition.

B. Plaintiffs below made no allegations of de jure acts

by the suburban districts. The District Court and

the panel of this Court concluded that such allegations

and proof against suburban school districts themselves

were not a prerequisite for implementation for relief

extending beyond the school districts of Detroit. There

may be proof of such discriminatory acts, but

that is not the theory on which the case was tried. As

no allegations of discrimination were made against

the suburban school district, they have no right to

be heard on such non-existent claims.

C. Plaintiffs Responses IB, 1-6 and 2B, 1-5 show that

remedy extending beyond the school district boundary

of the city of Detroit is not premised upon a single

factual finding that the Detroit school district is

predominantly black.

D. Defendants' apparent obsession with the phrase

"vicarious liability" simply should not obvfyscate

the traditional l4£h Amendment constitutional analysis

which requires that those who are parties to a lawsuit

who have remedial powers, as imposed by state law

and residual constitutional duty, provide relief

upon a showing of unconstitutional "state action."

This is not "vicarious liability" in a tortes- sense;

but rather is the fiction which has been utilized

At p. 11, State Defendants' Argument:

ever since ex parte Young to insure that the 14th

Amendment is not ham-strung by the 11th Amendment,

to give a meaning to the 11th Amendment which does

not require that it be repealed but only re-interpreted

to permit enjoyment of the later enacted 14th Amendment.

10. At p. 13, state Defendants’ Argument:

School district boundaries which were not created and

maintained for the purpose of segregation are not a

violation of the United States Constitution and therefore

are not subject to judicial intervention.

Plaintiffs’ responses:

A. Unconstitutional purpose and effect are shown where

the maintenance of a school district boundary would ,

abridge otherwise constitutionally required rights

and remedies.

B. This is not a school district boundary gerrymander

case, except to the extent that it is obvious that

state action has maintained, and by Act 48 validated,

, and reimposed, the Detroit school district boundary as

. Cipa barrier /otherwise' unconstitutionally required ̂ siegre-

gation.

C. Absent a showing that the present arrangements are

necessary to the promotion of a compelling state

interest, school district boundaries are not any

limit to remedial relief or/limiting of plaintiffs

constitutional rights by some "balancing of interests."

On this record, the only reason for the existence of

the present arrangements is merely their present existence.' i •

n if a c] 7 tUsh-K-r ^x-r-o'A^&w^ts u/ero.

J , u.V Di CodA- n tff'-h Av.r\t» sraTdft>V/*V.:'- ' )

E. See also 5generally.)the other theori&sof the case authorizing

metropolitan relief on the record made in this case.

Plaintiffs’ response 2B-1-5 to the Grosse Pointe Petition.

In essence, the proof in this cause and the law with

respect to these other constitutional bases [extending

beyond the Detroit school district is a dramatic

example of the irrelevance of the ancient reasons for

the creation of ancient boundaries to present constitutional

rights. The discriminatory actions rampant

within the state system of education have both (1) dis

criminated against black children along school district

lines and served to identify Detroit as a black

school district, and (2) hss=e accomplished the pattern

of containment of blacks and whites in separate schools

without regard to school district boundary lines.

The panel has suggested an Austin "results" theory

as well. See Plaintiffs Response 2 B 4 to the Grosse

Pointe Petition. This results theory is merely an

extent ion of our arguments against the school by

school approach; in essence, it is an argument that

the school district boundary lines are irrelevant

to the state imposition of segregation. Where 175

schools are identified as black schools, the pattern of

"resulting" white schools is not limited to the

geographic boundaries of/Detroit school districts.

At p. 13, State Defendants' Argument:

At p. 66 ofc" its opinion, the panel states that there is

a vested tTtTTSS constitutional remedy to^thxs case^and

this is the same as saying that there is a vested constitu

tional right to a particular ratio of black to white

in a school district.

Plaintiffs' Responses:

The panel's opinion does not'state that there is a vested

right to a metro remedy, per se. Rather, the panel is

saying that the plaintiffs, once having shown a massive

violation's here, are entitled to complete relief: the

substitution of a system of "just schools" now and hereafter.

The District Court, having properly found that complete

relief cannot be accorded within the geographic limits

of the city of Detroit, therefore^was required to go beyond

the Detroit school district limits to accord complete

relief. This bears no relationship to the state defendants'

-j-ke. ôsRul̂rJ~*a<'i

argument that S;\sn* a vested constitutional right to a particular

ratio of black to white in a school district. See Plaintiffs'

Response 9A-D to Allen Park Petition and suggested

conclusion to argument.