Missouri v. Jenkins Brief of Respondents Jenkins in Opposition to Certiorari

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1988

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Missouri v. Jenkins Brief of Respondents Jenkins in Opposition to Certiorari, 1988. 57c1d5ff-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c797f961-b9c1-44ab-b91f-65304d3496ff/missouri-v-jenkins-brief-of-respondents-jenkins-in-opposition-to-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

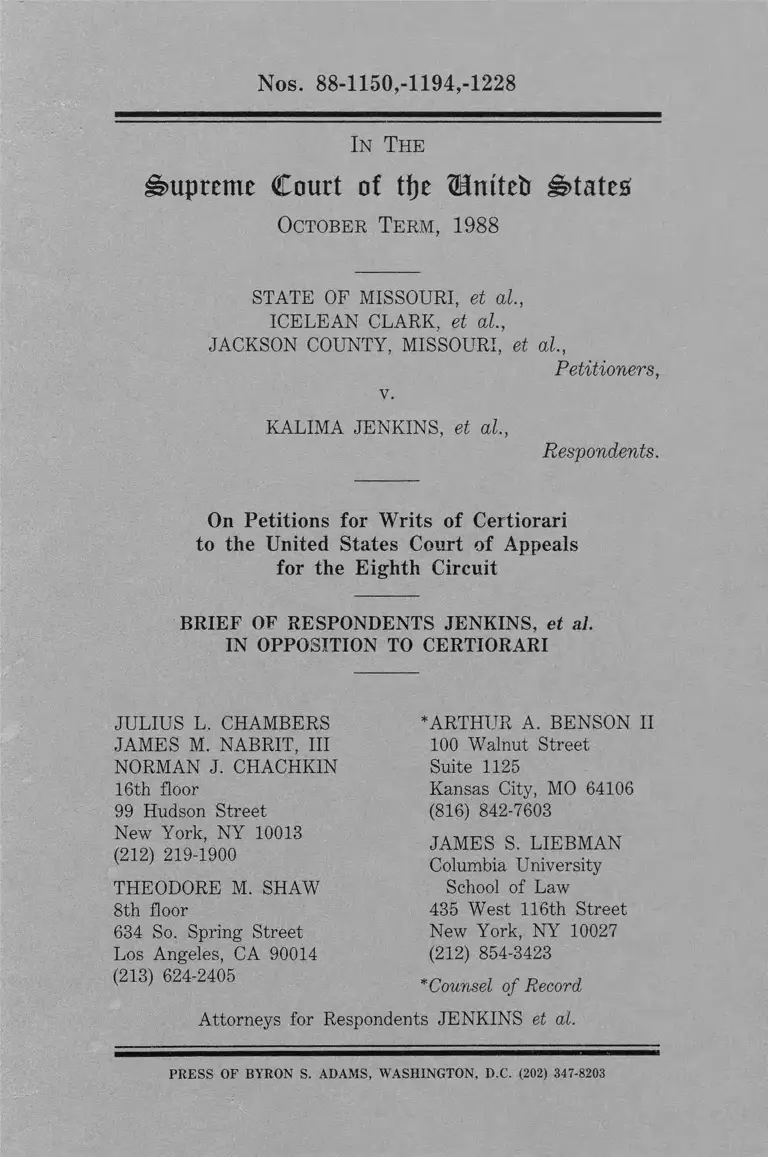

Nos. 88-1150,-1194,-1228

I n T h e

Supreme Court of tfje Hmtctr states

O c t o b e r T e r m , 1988

STATE OF MISSOURI, et a l,

ICELEAN CLARK, et al.,

JACKSON COUNTY, MISSOURI, et

v.

al.,

Petitioners,

KALIMA JENKINS, et al.,

Respondents.

On Petitions for Writs of Certiorari

to the United States Court of Appeals

for the Eighth Circuit

BRIEF OF RESPONDENTS JENKINS, et al.

IN OPPOSITION TO CERTIORARI

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

16th floor

99 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

THEODORE M. SHAW

8th floor

634 So. Spring Street

Los Angeles, CA 90014

(213) 624-2405

* ARTHUR A. BENSON II

100 Walnut Street

Suite 1125

Kansas City, MO 64106

(816) 842-7603

JAMES S. LIEBMAN

Columbia University

School of Law

485 West 116th Street

New York, NY 10027

(212) 854-3423

*Counsel of Record

Attorneys for Respondents JENKINS et al.

PRESS OF BYRON S. ADAMS, WASHINGTON, D.C. (202) 347-8203

Counter-Statement of Questions Presented

1. Whether the petitions are all jurisdictionally out of

time.

2. Whether a federal district court, which has made

detailed findings (upheld by the Court of Appeals)

documenting long-maintained racial discrimination and

segregation in the Kansas City, Missouri School District

(KCMSD) and the extensive and continuing effects of

that constitutional violation, should seek to fashion relief

that will (insofar as possible) achieve the goal of

providing students in the KCMSD with the same quality

of integrated educational opportunities that the court

determines would exist if the violation had not occurred.

3. Whether a federal district court, in such

circumstances, should withhold relief that is adequate to

- i -

redress the educational harms occasioned by the

constitutional violation -- in order to avoid the necessity

of issuing a decree against state or local officials

requiring them to raise funds (including by increasing tax

levies) sufficient to implement a complete remedy for

the violation.

4. Whether a federal district court, in such

circumstances, lacks the power to effectuate a complete

remedy for violations of the Fourteenth Amendment by

directing that tax levies be increased in order to provide

the revenue necessary 'to afford relief to the victims of

unconstitutional discrimination and school segregation.

5. Whether a federal district court, in such

circumstances, properly denied intervention to individuals

and governmental entities whose petitions were not

- 11 -

submitted until after the tax levy measures which they

sought to challenge had been ordered, despite the court’s

earlier announcement that it was likely to

which would raise tax levies in order

implementation of an adequate remedy for

take action

to assure

serious and

sustained Fourteenth Amendment violations.

Table of Contents

Page

Counter-Statement of Questions Presented i

Table of Authorities vi

Jurisdiction 1

Counter-Statement of the Case 3

REASONS FOR DENYING THE W RITS-

Introduction 3

I This Case Does Not Merit Review Because

The Remedy Ordered By The District Court

Is Appropriately Designed To Redress The

Proven Constitutional Violations And Their

Effects, And It Does Not Exceed The Scope

Of The Trial Court’s Broad Equitable Power

To Afford Complete Relief To The Victims

Of Unconstitutional Segregation 11

A. The district court did not require a

magnet plan "to attract additional non

minority students" for the purpose of

transforming the KCMSD into "a district

. . . with some particular number of

white and black students" 14

- IV -

B. The district court’s goal of achieving

comparability between KCMSD’s

facilities and programs with the average

of those of surrounding systems was a

reasonable starting point in the

formulation of a remedy to eliminate

the effects of the proven constitutional

violations 24

II The District Court’s Order Directing The

Collection, For A Limited Period Of Time, Of

Additional Property Tax Revenues Within The

KCMSD Adequate To Support The District’s

Share Of The Remedial Costs Is An

Appropriate Exercise Of Its Equitable

Remedial Authority To Effectuate The

Fourteenth Amendment To The Constitution 41

A. The authority of federal courts in school

desegregation suits to require local tax

levy and collection in order to effectuate

relief necessary to vindicate Fourteenth

Amendment rights was settled in Griffin

and this case fits squarely under that

ruling 43

B. Apart from Griffin, the power of federal

courts, in appropriate circumstances, to

order state tax levies to be made is not

in doubt 54

Conclusion 62

- v

Table of Authorities

Cases:

Arthur v. Nyquist, 712 F.2d 809

(2d Cir. 1983), cert, denied,

466 U.S. 936 (1984) 16n

Berry v. School Dist. of Benton

Harbor, 698 F.2d 813 (6th Cir.),

cert, denied, 464 U.S. 892 (1983) 16n

Brittingham v. Commissioner, 451

F.2d 315 (5th Cir. 1971) 59n

Burger v. Kemp, 483 U .S .___, 97 L.

Ed. 2d 638 (1987) 22n

Clay County v. United States ex rel.

McAleer, 115 U.S. 616 (1885) 60n

Columbus Bd. of Educ. v. Penick,

443 U.S. 449 (1979) 16n, 22n

Couch v. City of Villa Rica, 203 F.

Supp. 897 (N.D. Ga. 1962) 57n, 60n

County of Lincoln v. Luning, 133

U.S. 529 (1890) 59n

Page

- v i -

Table of Authorities (continued)

Page

Cases (continued):

Davis v. Board of School Commr’s,

402 U.S. 33 (1971) 26

Davis v. East Baton Rouge Parish

School Bd., 721 F.2d 1425

(5th Cir. 1983) 16n, 20n, 23n

Diaz v. San Jose Unified School

Dist., 861 F.2d 591 (9th Cir.

1988)

Fitzpatrick v. Bitzer, 427 U.S.

445 (1976)

Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co.,

482 U.S. 96 L. Ed. 2d

572 (1987)

Graham v. Folsom, 200 U.S. 248

(1906)

Green v. County School Bd. of New

Kent County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968) 15n

Griffin v. Board of Supervisors

of Prince Edward County, 339

F.2d 486 (4th Cir. 1964) 52n

16n

59n

22n

58n

- Vll -

Table of Authorities (continued)

Cases (continued):

Griffin v. County School Bd. of

Prince Edward County, 377

U.S. 218 (1964)

Haggard v. Tennessee, 421 F.2d

1384 (6th Cir. 1970)

Hart v. Community School Bd.,

512 F.2d 37 (2d Cir. 1975)

Heine v. Levee Comm’rs, 86 U.S.

655 (1874)

Hoots v. Pennsylvania, 539 F.

Supp. 335 (W.D. Pa. 1982),

affd, 703 F.2d 722 (3d

Cir. 1983)

Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S.

385 (1969)

Hutto v. Finney, 437 U.S. 678

(1978)

Imbler v. Pachtman, 424 U.S. 409

(1976)

43, 45-49, 51-54

59n

16n

59n

35n

41n

12n, 26n, 62

Page

- viii -

55n

Table of Authorities (continued)

Page

Cases (continued):

Jenkins v. Missouri, 855 F.2d

1295 (8th Cir. 1988) 8n, 9n, 21n

Jenkins v. Missouri, 672 F.

Supp. 400 (W. D. Mo. 1987),

aff d in part and rev’d in part,

855 F.2d 1295 (8th Cir. 1988)

Jenkins v. Missouri, 593 F. Supp.

1485 (W.D. Mo. 1984), 639 F.

Supp. 119 (W.D. Mo. 1985), modified

in part and affd, 807 F.2d 657 (8th

Cir. 1986)(en banc), cert, denied,

108 S. Ct. 70 (1987)

Liddell v. Bd. of Educ., 801 F.2d 278

(8th Cir. 1986)

Liddell v. Missouri, 731 F.2d 1294

(8th Cir.), cert, denied, 469 U.S.

816 (1984)

Louisiana v. Jumel, 107 U.S. 711 (1883)

Louisiana ex rel. Hubert v. Mayor of New

Orleans, 215 U.S. 170 (1909)

passim

passim

35n

16n, 50n

59n

60n

- IX -

Table of Authorities (continued)

Page

Cases (continued):

Louisiana ex rel. Ranger v. New Orleans,

102 U.S. 203 (1880) 60n

Meriwether v. Garrett, 102 U.S. 472 (1880) 57, 58, 59

Milliken v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267 (1977) 6,lln,16n,59n

Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 (1974) 4-5

Morgan v. Kerrigan, 530 F.2d 401 (1st

Cir.), cert, denied, 426 U.S. 935

(1976), subsequent proceeding sub

nom. Morgan v. McDonough, 689 F.2d

265 (1st Cir. 1982) 16n

Morgan v. Nucci, 617 F. Supp. 1316

(D. Mass. 1985), appeal dismissed, 831

F.2d 313 (1st Cir. 1987) 35n

New York State Ass’n for Retarded

Children v. Carey, 631 F.2d 162

(2d Cir. 1980) 44n

North Carolina State Bd. of Educ. v.

Swann, 402 U.S. 43 (1971) 53n, 60-61

- x -

Table of Authorities (continued)

Page

Cases (continued):

Plaquemines Parish School Bd. v. United

States, 415 F.2d 817 (5th Cir.

1969) 35n

Reece v. Gragg, 650 F. Supp. 1297

(D. Kan. 1986) 45n

Redman v. Terrebonne Parish School

Bd., 293 F. Supp. 376 (E.D.

La. 1967) 35n

Rees v. City of Watertown, 86 U.S. 107

(1874) 57, 58, 59n

Reitman v. Mulkey, 387 U.S. 369 (1967) 40n, 41n

Rhem v. Malcolm, 507 F.2d 333 (2d Cir.

1974) 44n

San Antonio Indep. School Dist. v.

Rodriguez, 411 U.S. 1 (1973) 36

Sanchez-Espinoza v. Reagan, 770 F.2d 202

(D.C. Cir. 1985) 57n

Singleton v. Anson County Bd. of

Educ., 283 F. Supp. 895 (W.D.N.C.

1968) 35n

- xi -

Table of Authorities (continued)

Page

Cases (continued):

Stansbury v. United States, 75 U.S. 33

(1869) 55n

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of

Educ., 402 U.S. 1 (1971) 26, 35n

Tasby v. Estes, 412 F. Supp. 1192 (N.D.

Tex. 1976), remanded on other

grounds, 572 F.2d 1010 (5th Cir.

1978) 35n

United States v. County Court, 99 U.S.

582 (1879) 60n

United States v. County Court, 95 U.S.

769 (1878) 60n

United States v. Jefferson County

Bd. of Educ., 380 F.2d 385 (5th

Cir.)(en banc), cert, denied sub

nom. Caddo Parish School Bd. v.

United States, 389 U.S. 840 (1967) 35n

United States v. Pittman, 808 F.2d

385 (5th Cir. 1987) 20n

United States v. Texas Educ. Agency,

679 F.2d 1104 (5th Cir. 1982) 16n

- xii -

Table of Authorities (continued)

Page

Cases (continued):

United States v. Yonkers Bd. of Educ.,

856 F.2d 7 (2d Cir. 1988) 35n

United States v. Yonkers Bd. of Educ.,

837 F.2d 1181 (2d Cir. 1987), cert.

denied, 108 S. Ct. 2821 (1988) 16n

United States ex rel. Hoffman v.

Quincy, 71 U.S. 535 (1867) 60n

United States ex rel. Ranger v.

New Orleans, 98 U.S. 381 (1879) 54n-55n

United States ex rel. Wolff v.

New Orleans, 103 U.S. 358 (1881) 55n

Washington v. Seattle School Dist.

No. 1, 458 U.S. 457 (1982) 41n

Washington v. Washington State

Commercial Passenger Fishing

Vessel Ass’n, 443 U.S. 658,

modified sub nom. Washington v.

United States, 444 U.S. 816 (1979) 53n, 61

Yost v. Dallas County, 236 U.S. 50 (1915) 59n, 61n

Table of Authorities (continued)

Page

Statutes:

28 U.S.C. § 2101(c) (1982) 2

42 U.S.C. § 1983 (1982) 55n

Education for Economic Security Act,

Pub. L. No. 98-670, 98 Stat. 1267 (1984) 17n

Augustus F. Hawkins-Robert T. Stafford

Elementary and Secondary School

Improvement Amendments of 1988,

Pub. L. No. 100-297, 102 Stat. 231 (1988) 17n

Rules:

Fed, R. App. P. 35 2n

Fed. R. App. P. 40 2n

Fed. R. App. P. 41 2n

Fed. R. Civ. P. 81(b) 56n

Sup. Ct. Rule 20.4 2n

- xiv -

Table of Authorities (continued)

Page

Other Authorities:

Remarks on Signing the Augustus F.

Hawkins-Robert T. Stafford Elementary

and Secondary School Improvement

Amendments of 1988, 24 Weekly Comp,

of Pres. Doc. 540 (April 28, 1988) 17n

S. Rep. No. 100-222, 100th Cong., 1st Sess.

(1987), reprinted in 3 1988 U.S. Code Cong.

& Adm. News 149 (June, 1988) 16n-17n

- xv -

In the

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1988

Nos. 88-1150, -1194, -1228

STATE OF MISSOURI, et al..

ICELEAN CLARK, et al..

JACKSON COUNTY, MISSOURI, et al..

Petitioners.

v.

KALIMA JENKINS, et al.

On Petitions for Writs of Certiorari

to the United States Court of Appeals

for the Eighth Circuit

BRIEF OF RESPONDENTS JENKINS, et al.

IN OPPOSITION TO CERTIORARI

Jurisdiction

None of the petitions to which this response is

addressed was filed within 90 days of the issuance of the

final judgment below on August 19, 1988, as required by

28 U.S.C. § 2101(c) (1984),1 nor was timely application

for extension sought and granted by this Court or a

Justice of the Court. Therefore, for the reasons

articulated in the Brief in Opposition of Respondent

Kansas City, Missouri School District (KCMSD) in these

matters, in which the Jenkins respondents join, this

Court lacks jurisdiction to grant the present petitions.1 2

This fact alone is a sufficient basis for denying the writs.

1Rule 20.4 of this Court, which tolls the 90-day period for

filing a petition only if a timely petition for rehearing is filed, is

consistent with Rules 35, 40 and 41, Fed. R. App. P., which

establish an automatic stay of the issuance of a Court of Appeals’

mandate during the pendency of a timely petition for rehearing but

state explicitly that the pendency of a suggestion of rehearing in

banc "shall not affect the finality of the judgment of the court of

appeals or stay the issuance of the mandate" [Rule 35(c)].

2We have lodged with the Clerk of this Court ten copies of the

Petitions for Rehearing En Banc filed below. Examination of these

documents establishes that none of the present Petitioners requested

rehearing; rather, all sought rehearing in banc. There were thus no

"petitions for rehearing" subject to being denied as provided in the

amended mandate of the Court of Appeals issued sua sponte on

January 10, 1989 (see State Pet. at A-l).

- 2 -

Counter-Statement of the Case

The Jenkins respondents join in the KCMSD

respondents’ Counter-Statement.

REASONS FOR DENYING THF, WRITS

Introduction

The instant Petitions concern aspects of orders issued

by the United States District Court for the Western

District of Missouri in the final, remedial stages of

protracted, complex, school desegregation litigation

involving the Kansas City, Missouri public schools. The

district judge who issued these orders has presided over

the action since its initiation in 1977. He has observed

and heard hundreds of witnesses, including scores with

educational or other academic, as well as practical,

expertise. He has considered thousands of documentary

- 3 -

and other exhibits, has personally viewed the KCMSD

school facilities, and has issued numerous opinions and

orders containing specific, detailed and particularized

findings of fact that provide the foundation for his legal

determinations and orders.

The district court’s major conclusions and actions

have been severely criticized, at different times, by both

sides in the litigation but, with only minor exceptions,

panels of the Court of Appeals and a majority of the

Court sitting en banc have sustained the trial judge’s

careful fashioning of a remedy appropriate to the nature

and scope of the constitutional violations which he

found.

First, following lengthy trial proceedings, the district

judge applied this Court’s ruling in Milliken v. Bradley.

- 4 -

418 U.S. 717 (1974)(Milliken__I) and rejected the

contentions of the Jenkins and KCMSD respondents

here, that the proof justified an inter-district remedy

involving pupil reassignments between and/or

consolidation of the KCMSD and nearby suburban

school systems. The court also held that the historic

pre- and post-Brown constitutional violations by the

KCMSD and the State of Missouri had never been

redressed but that their effects had been exacerbated by

delay and neglect of the defendants’ affirmative

constitutional obligations for decades. It directed that

the continuing effects of these violations should be

ameliorated through a remedial plan involving voluntary

inter-district assignments, creation of integrated magnet

schools in the KCMSD, improvement of the KCMSD’s

capital plant and of its educational programs to correct

- 5 -

deficiencies attributable to the long period of segregated

operation, and implementation of special programs to

address educational deficiencies created by that

segregation, see Milliken v. Bradley. 433 U.S. 267

(1977)(MilHken__II). With the exception of some

alterations in the allocation of remedial costs between

the KCMSD and the State of Missouri, all of these

determinations were approved by the Court of Appeals,

and this Court declined to review the denial of

mandatory inter-district relief. Jenkins v. Missouri. 593

F. Supp. 1485 (W.D. Mo. 1984), 639 F. Supp. 19 (W.D.

Mo. 1985), modified in part and affd, 807 F.2d 657 (8th

Cir. 1986)(en banc), cert, denied. 108 S. Ct. 70 (1987).

Thereafter, the district court continued closely to

supervise the refinement and implementation of the

- 6 -

remedy3 for the constitutional violations which it found,

proceeding in step-by-step fashion.4 It approved and

rejected remedial components suggested by all parties,

including the State of Missouri and the Jenkins and

KCMSD respondents.5 It has sought to achieve a fair

3E.g., State Pet. App. [hereinafter Pet. App.] 104a, 106a

(approving continuation of two programs for 1987-88 to "give the

KCMSD another year to meet the projected enrollments"); 639 F.

Supp. at 46, Pet. App. 129a (requiring KCMSD to submit a detailed

plan for improving public information about its desegregation plan

in light of inadequate results after prior order allocating funds for

this purpose); 639 F. Supp. at 50-51, Pet. App. 137a-138a (ordering

further reports on implementation of educational programs under

decree).

4See. e.g.. Pet. App. 77a (approving capital program only for

projects scheduled to be completed by fall of 1990); id. at 79a

(approving budget for construction project management team for

three years only); jd. at 191a (approving only initial capital

improvement plan and postponing consideration of additional

measures); 639 F. Supp. at 45, Pet. App. 199a (suspension of tax

rollback for one year only to "provide the KCMSD with an

opportunity to present a tax levy proposal to its patrons at the next

regularly scheduled school election”).

5See, e.g.. 639 F. Supp. at 32-33, Pet. App. 173a (ordering

implementation of State’s Early Childhood program); Pet. App. 65a

(rejecting KCMSD’s and Jenkins’ suggested regulations for tax

collection); id. at 95a (declining to order central coordination of

school-based programs sought by KCMSD); id. at 118a-19a

(requiring KCMSD to bear cost of renovating building to house

temporary performing arts magnet); 639 F. Supp. at 49, Pet. App.

(continued...)

- 7 -

and equitable allocation of the costs of constitutional

compliance between the two joint tortfeasors, the State

of Missouri and the KCMSD.5 6 The parties have

vigorously contested the litigation at the remedial stage;

the judgment of the Court of Appeals of which

Petitioners seek review resolved consolidated appeals

from some thirteen separate orders issued by the trial

court.7 This time, the principal appellants were the

State of Missouri and state officials. Again, however,

5(...continued)

135a (rejecting KCMSD’s requested expansion of before- and after

school programs).

6E.g.. Pet. App. 79a (requiring KCMSD to pay 50%, rather

than 25% of capital construction costs because "the KCMSD will

continue to benefit from the[ new facilities construction] long after

the hopeful success of the desegregation plan has been realized");

id. at 107a (adjusting budget to account for savings in expenditures

at other schools as new magnets open); kL at 109a (requiring

KCMSD to bear ongoing maintenance costs for facilities constructed

or improved under decree).

7Jenkins v. Missouri. 855 F.2d 1295, 1299 n.2 (8th Cir. 1988),

Pet. App. 4a n.2.

- 8 -

with minor modifications and reversal only with respect

to one separable aspect concerning funding,8 the Court

of Appeals approved the trial judge’s careful supervision

of this action.

It is against this background of painstaking attention

by a district court with intimate familiarity with the

particularities of the case, and whose actions have been

almost wholly sustained on two occasions by the Court of

Appeals, that this Court must assess the necessity and

desirability of reviewing the judgment below.

8The Court of Appeals sustained the district court’s order

raising the property tax millage in the KCMSD because "the

property tax is the established source of revenue for Missouri school

districts" and the order was the functional equivalent of "setfting]

aside restrictions or limitations imposed by state law that impede

the disestablishment of a dual school system" (855 F.2d at 1315, Pet.

App. 39a-40a). It reversed that portion of the court’s orders that

imposed an income tax surcharge on individuals working within the

KCMSD because "the income tax surcharge restructures the State’s

scheme of school financing and creates an entirely new form of

taxing authority" (855 F.2d at 1315, Pet. App. 40a).

- 9 -

Petitioners raise only a few issues.9 Despite the

provocative language of their filings, none of the

questions they seek to present warrants the plenary

attention of this Court because, as we show below, the

lower courts have faithfully and unexceptionably applied

well established legal principles and followed the

decisions of this Court.

Petitioners in Nos. 88-1194 and 88-1228 sought intervention in

this litigation in the district court, which was denied on the grounds

that their requests were untimely; that denial was affirmed by the

court below. The only question properly presented by these arties,

therefore, is the correctness of the ruling affirming the denial of

intervention.

Petitioners in No. 88-1150 do not contest either their own

liability or the general remedial approach of the district court

(improvements of KCMSD’s capital facilities and educational

programs together with the creation of magnet schools to bring

about desegregation through voluntary means), an approach that

they supported in the trial court, see infra note 12. Instead, they

charge, first, that the district court has shaped the particulars of this

remedial approach to achieve goals other than the effective

dismantling of the long-maintained dual system of schools in the

KCMSD. Second, they assert that the district court was without

power to require the KCMSD to provide a portion of the resources

necessary to implement the remedy through an increase in its

property tax levy (a requirement which the court imposed only after

both the KCMSD electorate and the State legislature had refused or

failed to create a reliable funding mechanism for this purpose).

- 10 -

I

This Case Does Not Merit Review Because The

Remedy Ordered By The District Court Is

Appropriately Designed To Redress The Proven

Constitutional Violations And Their Effects, And

It Does Not Exceed The Scope Of The Trial

Court’s Broad Equitable Power To Afford

Complete Relief To The Victims of

Unconstitutional Segregation

This is a case in which the extensive and continuing

harmful effects of the long-sustained constitutional

violations committed by the State of Missouri and the

KCMSD were identified with precision and detail in

exhaustive proceedings before the district court. On that

record, the trial court was charged, in fashioning a

remedy, with the obligation of "restor[ing] the victims of

discriminatory conduct to the position they would have

occupied in the absence of such conduct."10 In the

10Milliken II. 433 U.S. at 280.

- 11 -

orders affirmed below, in those previously reviewed by

the Court of Appeals, and through its exercise of

continuing jurisdiction during the transition from a dual

school system, the district court has sought to provide a

complete remedy that will be practicable, workable, and

successful.11

Petitioners contest neither liability nor the broad

outlines of the relief ordered by the trial court.12

11 The trial court described its responsibility and authority as

follows:

. . . [T]he goal of a desegregation decree is clear. The goal

is the elimination of all vestiges of state imposed

segregation. In achieving this goal, the district court may

use its broad equitable powers, recognizing that these

powers do have limits. Those limits include the nature and

scope of the constitutional violation, the interests of state

and local authorities in managing their own affairs

consistent with the constitution, and insuring that the

remedy is designed to restore the victims of discriminatory

conduct to the position they would have occupied in the

absence of such conduct.

(639 F. Supp. at 23, Pet. App. 153a.) See Hutto v. Finney, 437

U.S. 678, 688 & n.12 (1978).

12See, e.g., 593 F. Supp. at 24, Pet. App. 155a ("No party to

(continued...)

- 12 -

Implicitly recognizing the difficulties inherent in asking

this Court to entertain questions that are fact-bound and

unique to the circumstances of an individual case,

Petitioners have wrenched language in the district court’s

opinions out of context in an effort to describe legal

questions more susceptible of being characterized as

worthy of this Court’s discretionary review. A fair

reading of the district court’s orders demonstrates, 12

12(...continued)

this case has suggested that this plan should not contain

components designed to improve educational achievement. In fact,

it is ’appropriate to include a number of properly targeted

educational programs in a desegregation plan’ (State Plan at 5)");

593 F. Supp. at 26, Pet. App. 158a ("both the State of Missouri and

the KCMSD endorse achieving AAA status, reducing class size at

the elementary and secondary level, summer school, full day

kindergarten, before and after school tutoring and early childhood

development programs"); 593 F. Supp. at 40, Pet. App. 189a ("The

State (State Plan p. I l l ) proposes a $20,000,000 facilities

improvement program with the state making a one time

contribution not to exceed $10,000,000. . . . The State does not

dispute that there are serious structural and environmental problems

throughout the facilities utilized by the KCMSD"); 855 F.2d at 1299,

Pet. App. 5a ("In this case the district court dealt with undisputed

constitutional violations and its series of orders were necessary to

remedy the lingering results of these violations, since local and state

authorities had defaulted in their duty to correct them.").

- 13 -

however, that the legal issues relating to the goals of the

remedy that are posited by Petitioners simply do not

arise in this matter.

A. The district court did not require a magnet plan "to

attract additional non-minority students" for the

purpose of transforming the KCMSD into "a district

. . . with some particular number of white and black

students"

The State’s Petition attacks the scope of the magnet

school program to be established in the KCMSD under

the district court’s orders:

No other court has required a district to turn

most of its schools into magnet schools, and no

other court has imposed a duty to attract more

students of a designated race. . . . [Tjhe right at

issue . . . is not [a right] to be enrolled in a

district or school with some particular number of

white and black students.

(Pet. at 15.) The State simply ignores the trial court’s

- 14 -

lucid elaboration of the basis for its magnet school

requirements.

In its initial remedial order the court recognized its

obligation "to further explore any reasonable potential

for achieving further desegregation" of the KCMSD

schools (639 F. Supp. at 38, Pet. App. 184a). It declined

to order mandatory reassignments within the KCMSD

[u]nless and until th[e study suggested by the

State of Missouri] or other studies show that

further mandatory student reassignment can

achieve additional desegregation without

destabilizing the desegregation which presently

exists.

(Id.)13 On the other hand, the district court had heard

evidence from a number of expert witnesses that

"[m]agnet schools can be utilized to assist the State of

13Cf. Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent County. 391

U.S. 430, 441 (1968)(voluntary enrollment option may have a place

in a desegregation plan in the absence of alternatives "promising

speedier and more effective conversion to a unitary, nonracial

school system").

- 15 -

Missouri and the KCMSD in expanding desegregative

educational experiences for its students" (639 F. Supp. at

34, Pet. App. 176a), and it required submission of a plan

to utilize this voluntary desegregation tool (639 F. Supp.

at 34-35, Pet. App. 177a).14

14The concept of a magnet school is to offer a different,

improved or unique curriculum or service (such as before- or after

school day care) that will attract voluntary attendance by students of

all races. This Court has approved of magnet schools as a

desegregation tool on a number of occasions. See, e.g., Milliken II.

433 U.S. at 272; Columbus Bd. of Educ. v. Penick. 443 U.S. 449,

488 (1979), and the courts of appeals and district courts have

consistently approved desegregation plans incorporating magnet

schools as an laltemative to mandatory and involuntary

reassignments of students. See Diaz v. San Jose Unified School

Dist„ 861 F.2d 591, 596 (9th Cir. 1988); United States v. Yonkers

Bd. of Educ,. 837 F.2d 1181, 1238 (2d Cir. 1987), cert, denied. 108

S. Ct. 2821 (1988); Liddell v. Missouri. 731 F.2d 1294, 1310 (8th

Cir.), cert, denied. 469 U.S. 816 (1984); Davis v. East Baton Rouge

Parish School Bd.. 721 F.2d 1425, 1440 (5th Cir. 1983); Arthur v.

Nvquist. 712 F.2d 809, 811-13 (2d Cir. 1983), cert, denied. 464 U.S.

892 (1983); Berry v. School Dist. of Benton Harbor, 698 F.2d 813

(6th Cir.), cert, denied. 464 U.S. 892 (1983); United States v. Texas

Educ. Agency. 679 F.2d 1104 (5th Cir. 1982); Morgan v. Kerrigan,

530 F.2d 401, 428 (1st Cir.), cert, denied. 426 U.S. 935 (1976),

subsequent proceeding sub nom. Morgan v. McDonough. 689 F.2d

265, 276 n.18 (1st Cir. 1982); Hart v. Community School Bd.. 512

F.2d 37, 54-55 (2d Cir. 1975).

The Congress and the President have also expressed

unambiguous support for magnet programs as an effective and

unintrusive remedy for school segregation. See S. Rep. No. 100-

(continued...)

- 16 -

The Court subsequently approved implementation of

three magnet schools or clusters in the 1986-87 school

year to "expan[d] the desegregative educational

experience for KCMSD students" and to assess the

potential success of this desegregation device:

The magnet plan must be geared toward both

remedial and desegregative goals and should

maximize achievement of desegregation with a

minimum amount of resources. The magnet

program should provide long term stability in

terms of future financing as well as incorporate a

carefully designed marketing program based upon

a careful analysis of the plans’ impact upon other

components of the desegregation plan. Thus,

future development of a magnet school program 14

14(...continued)

222, 100th Cong., 1st Sess. 48 (1987)("Research has shown that

magnet schools are the most successful means for promoting racial

desegregation"), reprinted in 3 1988 U.S. Code Cong. & Adm. News

149 (June, 1988); Remarks on Signing the Augustus F. Hawkins-

Robert T. Stafford Elementary and Secondary School Improvement

Amendments of 1988, 24 Weekly Comp, of Pres. Doc. 540 (Apr. 28,

1988) (President Reagan "pleased to note that the bill reauthorizes

the magnet school program and expands parental choice"); Hawkins-

Stafford Amendments of 1988, Pub. L. No. 100-297, § 3993, 102

Stat. 231 (1988)(to be codified at 20 U.S.C. § 3023); Education for

Economic Security Act, Pub. L. No. 98-670, § 703, 98 Stat. 1267,

1299 (1984).

- 17 -

need not duplicate this initial phase of the

magnet school effort.

(639 F. Supp. at 53, 55, Pet. App. 145a, 149a.) Based

upon initial experience with these magnets and upon

evidence adduced at additional hearings, the court

ultimately determined to approve KCMSD’s plan to

establish a substantial number of magnet schools.

However, the court’s Order makes it clear that the

fundamental basis for "turn[ing] most of [KCMSD’s]

schools into magnet schools," as the State puts it, is to

avoid the inequity which would occur if black students

- the victims of the State’s and KCMSD’s protracted

unconstitutional conduct — were restricted in their

opportunities to benefit from the improved or unique

educational experiences to be offered in magnet schools:

The plan magnetizes such a large number of

schools that every high school and middle school

student will attend a magnet school. At the

- 18 -

elementary level, there would be a sufficient

number of magnets to permit every student

desiring to attend a magnet school to do so. The

Court is opposed to magnetizing only a limited

number of schools in a district . . . . In each

[magnet] school there is a limitation as to the

number of students who may be enrolled. Thus,

for each non-minority student who enrolls in the

magnet school a minority student, who has been

the victim of past discrimination, is denied

admittance. While these plans may achieve a

better racial mix in those few schools, the victims

of racial segregation are denied the educational

opportunity available to only those students

enrolled in the few magnet schools. This results

in a school system of two-tiers as it relates to the

quality of education. This inequity is avoided by

the KCMSD magnet school plan.

(Pet. App. 122a.)15

15As the Court of Appeals noted:

The State in its filings with the district court cautioned

about creation of a two-tiered system of schools in which

"existing schools are, or are perceived to be, markedly

inferior." Response of State to KCMSD motion for

approval of 1986-87 magnet programs, p. 12. The State’s

expert witness, Dr. Doyle, echoed this concern and

suggested that one way to avoid the problem was to

convert an entire school system to magnet schools. Tr.

376, 381-82, June 5, 1986. Another State’s witness, Dr.

Cooper, also agreed on cross-examination that the

comprehensiveness of the plan was a step in the right

(continued...)

- 19 -

In the following paragraph of its Order, the district

court did comment, as the State emphasizes, that

Most importantly, the Court believes that the

proposed magnet plan is so attractive that it

would draw non-minority students from the

private schools who have abandoned or avoided

the KCMSD, and draw in additional non-minority

students from the suburbs.

(Pet. App. 123a). However, that comment is quoted

entirely out of context by the State.15 16 It does not refer

15(...continued)

direction. Tr. 890, Sept. 18, 1986. The district court’s

finding regarding the need for the number of magnet

schools authorized by the plan is amply supported by the

State’s own evidence.

(855 F.2d at 1304, Pet. App. 15a.) Compare United States v.

Pittman. 808 F.2d 385, 393 (5th Cir. 1987)(Higginbotham, J.,

concurring) (warning that selective magnet schools exclude a large

number of "average’’ black students); Davis v. East Baton Rouge

Parish School Bd., 721 F.2d at 1437 n.10 (magnet plan could create

new dual system of white magnets and black regular schools).

16The complex analyses which undergird the district court’s

remedial orders in this case cannot be reduced to the two or three

phrases that are taken out of context and repeatedly intoned

throughout the Petition without seriously distorting the trial court’s

reasoning and actions. Unfortunately, the Petition contains

numerous erroneous and misleading characterizations of the

holdings below.

- 20 -

(continued...)

to the reasons for the district court’s approval of the

number of magnet schools provided by the plan.

Instead, it is the concluding sentence of an entirely new

paragraph of the Order in which the district court found

that the particular magnet themes and emphases

suggested in the KCMSD plan were likely to succeed in

attracting a desegregated enrollment.16 17 Thus, the State’s

16(...continued)

For one example, the State charges that "the court [of appeals]

means to . . . apply a far-reaching theory of ’but-for’ causation-one

that would make the State liable for an effect of desegregation.

rather than for effects of segregation itself" (Pet. at 17-18). In fact,

in the portion of its opinion to which the Petition makes reference,

the Court of Appeals sustained the district court’s orders on the

basis of the trial judge’s conclusion that the discriminatory and

segregative practices of the KCMSD had caused whites to leave or

avoid the system’s public schools. See 855 F.2d at 1302, Pet. App.

lla-12a. It was the State of Missouri itself which raised the

question of so-called "white flight from desegregation," and what the

State now terms a "far-reaching theory of ’but-for’ causation" is

merely the Court of Appeals’ rejection of the State’s contention

that there was an intervening, independent cause of white

enrollment loss in the KCMSD that excused the joint tortfeasors of

all responsibility to correct the effects of their prior constitutional

violations. See 855 F.2d at 1303, Pet. App. 13a.

17The entire paragraph is as follows:

- 21 -

(continued...)

tendentious argument that a majority-black school system

is not unconstitutional (Pet. 15-19) is simply beside the

point.17 18 The basis for the trial court’s approval of

17(...continued)

The Court also finds that the proposed magnet plan would

generate voluntary student transfers resulting in greater

desegregation in the district schools. The suggested magnet

themes include those which rated high in the Court

ordered surveys and themes that have been successful in

other cities. Therefore, the plan would provide both

minority and non-minority district students with many

incentives to leave their neighborhoods and enroll in the

magnet schools offering the distinctive themes of interest to

them. Most importantly, the Court believes that the

proposed magnet plan is so attractive that it would draw

non-minority students from the private schools who have

abandoned or avoided the KCMSD, and draw in additional

non-minority students from the suburbs.

18In addition to mischaracterizing the lower courts’

determinations, the State also attacks a number of the trial court’s

factual findings. Both the "two-Court rule,” see, e.g.. Burger v.

Kemp. 483 U .S .___, ___, 97 L. Ed. 2d 638, 651 (1987); Goodman

v. Lukens Steel Co.. 482 U.S. ___, ___, 96 L. Ed. 2d 572, 584

(1987), and this Court’s traditional reliance upon the district courts

in school desegregation cases, see Columbus Bd. of Educ. v. Penick.

443 U.S. at 457 n.6, 464, id. at 468 (Burger, C.J., concurring in the

judgment); id. at 469-71, 475-76 (Stewart, J. & Burger, C.J.,

concurring in the result), counsel against disturbing these findings.

In any event, the State’s contentions are not convincing. The

State charges the district court with making inconsistent findings in

its August 25, 1986 and June 5, 1984 Orders (see Pet. at 17 n.21).

In its earlier (1984) Order, while adjudicating the liability — not the

(continued...)

- 22 -

KCMSD’s magnet school submission was its conclusion

18(...continued)

remedy - portion of the case (see 593 F. Supp. at 1505, Pet. App.

240a), the district court had discussed "[p]art of plaintiffs’ evidence

of white flight to the suburbs consisting] of charts displaying the

transfer of student records from various KCMSD high schools to

surrounding districts over a 15-year period from 1958 to 1973." The

court rejected plaintiffs’ contentions that the evidence supported

imposition of inter-district liability because "there is no evidence

that the [suburban districts] enticed these families to move" and "the

numbers involved are too insignificant to have had a segregative

impact on the KCMSD or the [suburban districts]. White flight is

simply not a constitutional violation by any [suburban district]."

(June 5, 1984 Order, at 38-39.)

Then, in 1986 the trial court observed that it had

found that segregated schools, a constitutional violation,

has led to white flight from the KCMSD to suburban

districts, large number of students leaving the schools of

Kansas City and attending private schools and that it has

caused a systemwide reduction in student achievement in

the schools of KCMSD.

(August 25, 1986 Order, at 1-2.) These findings are not

inconsistent, as the State suggests. In the 1984 Order, the district

court did not find that there was no "white flight." Rather, it

refused to impose inter-district liability on the basis of "white flight"

because the suburban districts were overwhelmingly white in racial

composition irrespective of the movement of white pupils who left

the KCMSD (see, e.g.. June 5, 1984 Order at 45, 49, 51, 55, 62, 67-

70, 74-75, 79, 84-86, 91), and because the KCMSD schools remained

highly segregated by virtue of that district’s discriminatory practices

during the 1958-73 time period, irrespective of its racial

composition (see, e,g„ Pet. App. 211a-215a; Pet. App. 209a-210a

[discussing Davis v. East Baton Rouge Parish School Bd.. 721 F.2d

1425 (5th Cir. 1983) (rejecting similar argument that demographic

change was responsible for school segregation)]).

- 23 -

that this magnet plan was both most likely to be

successful in achieving actual desegregation and also

most equitable for black students in the district, not any

sort of desire to attain a specific racial balance in the

district’s schools.19

B. The district court’s goal of achieving comparability

between KCMSD’s facilities and programs with the

average of those of surrounding systems was a

reasonable starting point in the formulation of a

remedy to eliminate the effects of the proven

constitutional violations.

The State attacks the remedial orders in this action

that require capital improvements within the KCMSD,

19Indeed, as the State itself points out (Pet. at 18 n.22), neither

the district court nor the Court of Appeals has imposed any

requirement that some minimum number of white students from

outside the KCMSD boundaries enroll in the magnet schools. The

lower courts’ failure to do so fatally undercuts the State’s

contention that the magnet school plan was approved for the

purpose of satisfying some judicially created "duty to attract

additional non-minority students to a school district" so as to

change the KCMSD into a district "with some particular number of

white and black students" (Pet. at 15).

- 24 -

contending that the district court has read into the

"equal protection clause [a] require[ment] that a school

district . . . once-segregated [must be made] comparable

to neighboring districts" (Pet. at 13).20 This contention is

2<>The State has failed to raise this issue in a timely fashion

before this Court. On June 14, 1985, the district court directed that

KCMSD make capital improvements more extensive than those

which the State of Missouri had argued were appropriate in light of

the violation, specifically indicating that

[a]fter the submission of the $37,000,000 improvement plan,

KCMSD shall then review other capital improvements

needed in order to bring its facilities to a point comparable

with the facilities in neighboring suburban school districts.

(639 F. Supp. at 41, Pet. App. 191a.) The State appealed from this

capital improvements order, making the same arguments it now

raises in its Petition (compare, e.g.. 807 F.2d at 685 with Pet. at 7

and 639 F. Supp. at 40-41, Pet. App. 189a-190a). The Eighth

Circuit, en banc, affirmed the scope of the plan while modifying the

allocation of financial responsibility between the KCMSD and the

State, 807 F.2d at 685-86. The State chose not to seek review of

that ruling by this Court.

Since that time, additional renovations, improvements and

construction have been ordered, undertaken and/or completed,

subject to the equal allocation of costs directed by the Court of

Appeals in 1986. The additional, avoidable and wholly unexpected

financial burden which would be shifted from the State to some

other party - in all likelihood to the KCMSD and its taxpayers,

including the black parents and children who are the victims of the

long-continued constitutional violations in this case - if the capital

improvements orders were now overturned, provides a compelling

(continued...)

- 25 -

similar to the argument advanced by the defendants in

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1, 23-25 (1971), that because the student

assignment plan there was drawn with an awareness of

the overall proportion of minority pupils in the system, it

embodied a substantive right to a particular racial

balance. In Swann, this Court rejected the argument,

because the system-wide proportion had been employed

as a starting point to help determine whether the plan

would "achieve the greatest possible degree of

desegregation, taking into account the practicalities of

the situation," Davis v. Board of School Commissioners.

402 U.S. 33, 37 (1971).20 21 Here, it is similarly clear that

20(...continued)

reason why the State’s contentions that could have been raised in

1986 became the law of the case at that time and ought not be

entertained by this Court now.

21See also, e.g.. Hutto v. Finney, 437 U.S. at 685-86 & n.8.

- 26 -

the standard of comparability to suburban facilities was

employed by the district court as an operational guide,

not a substantive goal.

When the district court concluded the liability phase

of this case and turned its attention to the formulation

of an adequate remedy, it was confronted with a school

system in which the adverse effects of racial

discrimination and segregation were still very much in

evidence: "a system wide reduction in student

achievement" (639 F. Supp. at 24, Pet. App. 155a); a

school district which, alone among systems in the Kansas

City metropolitan area, lacked the state "AAA rating

[that] is a designation which communicates to the public

that a school system quantitatively and qualitatively has

the resources necessary to provide minimum basic

education to its students" (639 F. Supp. at 26, Pet. App.

- 27 -

159a); an "educational process [that] has been further

’bogged down’ in the KCMSD by a history of segregated

education" (639 F. Supp. at 28, Pet. App. 164a);22 and

school facilities whose "current condition . . . adversely

affects the learning environment . . . [because of] safety

and health hazards, educational environment

impairments, functional impairments, and appearance

impairments" (639 F. Supp. at 39, Pet. App. 187a).23

Accordingly, the court sought to devise a remedy that

would eliminate the continuing impact of the

violation.

22The court commented that while "[a] 11, regardless of race or

class or economic status, are entitled to a fair chance and to the

tools for developing their individual powers of mind and spirit to

the utmost, . . . [segregation in the KCMSD has resulted in this

promise going unkept" (639 F. Supp. at 24; Pet. App. 154a).

^In a later order, the district court characterized the KCMSD

school plant as having "literally rotted," 672 F.2d at 211, Pet. App.

86a.

- 28 -

For example, the court was persuaded by ”[t]he

testimony of all the educational experts [for all parties

that] . . . the schools in KCMSD, when provided with

adequate resources, sufficient staff development, and

proper teaching methods, can attain educational

achievement results more in keeping with the national

norms" (639 F. Supp. at 24, Pet. App. 156a). With

substantial agreement from the State of Missouri,24 the

court therefore required implementation of a wide

variety of innovative, supportive, and training programs

to restore the educational climate within the KCMSD.

To effectuate these aspects of the remedy, the court

^See, e ĵ., 639 F. Supp. at 25, Pet. App. 156a ("both the State

of Missouri and the KCMSD have proposed program components

designed to increase student achievement at the elementary and

secondary levels"); 639 F. Supp. at 26, Pet. App. 158a ("both the

State of Missouri and the KCMSD endorse achieving AAA status,

reducing class size at the elementary and secondary level, summer

school, full day kindergarten, before and after school tutoring and

early childhood development programs").

- 29 -

determined, on the basis of overwhelming evidence

placed before it, that substantial improvement of

KCMSD’s school buildings would be necessary:

The improvement of school facilities is an

important factor in the overall success of this

desegregation plan. Specifically, a school facility

which presents safety and health hazards to its

students and faculty serves both as an obstacle to

education as well as to maintaining and attracting

non-minority enrollment. Further, conditions

which impede the creation of a good learning

climate, such as heating deficiencies and leaking

roofs, reduce the effectiveness of the quality

education components contained in this plan.

(639 F. Supp. at 40, Pet. App. 188a.)25 The district

court has continued, throughout the subsequent course

of this litigation, to focus on capital needs that are

directly related to eliminating the continuing effects of

the violations and to the educational components of the

plan (e.g., 672 F. Supp. at 404, Pet. App. 70a-71a).

25Sce also 639 F. Supp. at 41, Pet. App. 190a.

- 30 -

As we have previously noted, the trial court

determined to institute magnet school options and to

solicit the participation of suburban school districts in a

voluntary inter-district transfer program to expand the

possibilities for achieving further desegregation of the

KCMSD (639 F. Supp. at 34-35, 38-39, Pet. App. 176a-

177a, 185a-187a). The court found that the successful

implementation of integrated magnet schools demanded

adequate plant, facilities and equipment.26 Thus, in its

initial remedial decree, the district court ordered

KCMSD to submit a first-year budget for its existing

magnet schools, to include "budget items which are

directly related to enhancing the full desegregative

drawing power of these schools" (639 F. Supp. at 34,

26As the district court stated, ”[t]he magnet school plan is

crucial to the success of the Court’s total desegregation plan and

the KCMSD cannot effectively implement the magnet programs

without special facilities" (672 F. Supp. at 406, Pet. App. 75a).

- 31 -

Pet. App. 177a), and the court thereafter approved both

operating and capital expenditures for the magnets (639

F. Supp. at 53, 54-55, Pet. App. 144a, 146a-148a). In

the 1987 Order on which the State focuses, the trial

court rejected the State’s capital program submissions in

part because "the State failed to estimate the cost

necessary to provide magnet facilities needed to

implement the long-range magnet school plan approved

by the Court on November 12, 1986" (672 F. Supp. at

404, Pet. App. 71a).

Because the capital improvements are tied to

effective implementation of the magnet schools and the

educational components of the desegregation plan, the

Petition is misleading in intimating that everything which

the district court ordered in September, 1987 "was

- 32 -

expressly designed to make KCMSD schools comparable

to suburban schools" (Pet. at 7-8).

In many of the areas given remedial attention,

performance standards that would assure that the effects

of the violation would be eliminated were readily

ascertainable. For instance, the Missouri State

Department of Elementary and Secondary Education

awards ratings (such as the AAA rating) to school

districts on the basis of annual evaluations and had

established and documented KCMSD’s deficiencies and

needs (see 639 F. Supp. at 26-28, Pet. App. 158a-163a).

With respect to reductions in class size, the court

accepted goals suggested by the KCMSD that were less

stringent and less costly than the recommendations made

- 33 -

by the Missouri State Board of Education (see 639 F.

Supp. at 28-30, Pet. App. 163a-168a).

As to capital improvements, the district court

articulated a set of standards that were closely related

both to the violations it had found and the other

remedial components it was ordering. First, the court

required "eliminating safety and health hazards" and

"correcting those conditions existing in the KCMSD

school facilities which impede the level of comfort,

needed for the creation of a good learning climate" (639

F. Supp. at 41, Pet. App. 191a). These goals were

directly responsive to the discrimination in the KCMSD

under the dual system.27 Second, the court recognized

27The State does not dispute the historically inferior quality of

black schools under the dual system in the KCMSD, which is in any

event established on this record. See, e.g.. Tr. 818-24, 1,743-46,

16,835. Nor did the State demonstrate — and the district court did

not make any finding - that the inadequacies attributable to the

dual system had been redressed prior to the time that a deferred

(continued...)

- 34 -

that the voluntary enrollment of white students in

KCMSD magnet schools would not be possible if those

schools continued to be perceived as inferior to 27

27(...continued)

maintenance program at all schools was made necessary by voter

refusal to approve bond issues for capital improvements, 639 F.

Supp. at 39, Pet. App. 187a. Thus, the capital improvements

ordered by the trial court in part correct pre-Brown inequalities that

were perpetuated and exacerbated within the KCMSD by the

district’s and the State’s failure to meet their affirmative obligations

to eliminate the vestiges of enforced segregation. See Swann v.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ.. 402 U.S. at 18 ("the first

remedial responsibility of school authorities is to eliminate invidious

racial distinctions. . . . Similar corrective action must be taken with

regard to the maintenance of buildings and the distribution of

equipment").

Capital improvements have been routinely ordered as

appropriate components of remedial decrees in desegregation cases.

See, e.g.. United States v. Yonkers Bd. of Educ., 856 F.2d 7 (2d Cir.

1988); Liddell v. Board of Educ.. 801 F.2d 278 (8th Cir. 1986);

Plaquemines Parish School Bd. v. United States. 415 F.2d 817, 831

(5th Cir. 1969); United States v. Jefferson County Bd. of Educ.. 380

F.2d 385, 393-94 (5th Cir.)(en banc'), cert, denied sub nom. Caddo

Parish School Bd. v. United States. 389 U.S. 840 (1967); Morgan v.

Nucci. 617 F. Supp. 1316, 1318 (D. Mass. 1985), appeal dismissed.

831 F.2d 313 (1st Cir. 1988); Hoots v. Pennsylvania. 539 F. Supp.

335, 338 (W.D. Pa. 1982), affd, 703 F.2d 722 (3d Cir. 1983); Tasbv

v. Estes. 412 F. Supp. 1192, 1219 (N.D. Tex. 1976), remanded on

other grounds. 572 F.2d 1010 (5th Cir. 1978); Singleton v. Anson

County Bd. of Educ.. 283 F. Supp. 895, 903 (W.D.N.C. 1968);

Redman v. Terrebone Parish School Bd.. 293 F. Supp. 376, 379

(E.D. La. 1967).

- 35 -

alternative educational opportunities available to these

students.28 For this reason, the court required that

renovation and construction plans also take into account

"improving [KCMSD’s] facilities to make them visually

attractive" and "comparable with the facilities in

neighboring suburban school districts" (639 F. Supp. at

41, Pet. App. 191a). This goal was not, however,

devised by the trial court to obliterate "[differences in

local school funding" or to transform "a ’system of school

financing [which] results in unequal expenditures between

children who happen to reside in different districts . .

(Pet. at 19-20, quoting San Antonio Indep. School Dist.

v. Rodriguez. 411 U.S. 1, 54-55 (1973)). Rather, it

represents the starting point in designing a remedy for

^Cf. 639 F. Supp. at 26, Pet. App. 159a (KCMSD only district

in metropolitan area not rated "AAA").

- 36 -

the constitutional violations that is adequate and

workable:

The long term goal of this Court’s remedial order

is to make available to all KCMSD students

educational opportunities equal to or greater than

those presently available in the average Kansas

City, Missouri metropolitan suburban school

district. In achieving this goal the victims of

unconstitutional segregation will be restored to

the position they would have occupied absent

such conduct, while establishing an environment

designed to maintain and attract non-minority

enrollment.

(639 F. Supp. at 54, Pet. App. 145a-146a [emphasis in

original deleted and emphasis added].) Simply put, the

.Standard of general comparability to the average school

system in the geographic area was utilized as a practical

mechanism for identifying the educational opportunities

and facilities that were denied to KCMSD’s black

students as a result of the practices of racial segregation

and discrimination,29 and for assuring the likely success

29"[T]he Court has the responsibility of providing the victims of

(continued...)

- 37 -

of the magnet options.30

Petitioners strain to fashion some legal issue worthy

of review by claiming that there was no "state action"

which justifies the capital improvements orders because,

as the State argued unsuccessfully to the trial court, "’the

present condition of the district school facilities is not

traceable to unlawful segregation but is due to a lack of

maintenance by the KCMSD’" (Pet. at 7) and, it asserts,

"[tjhere is no conceivable way that a KCMSD resident,

entering a voting booth to support or oppose a tax

(...continued)

unlawful segregation with the educational facilities that they have

been unconstitutionally denied. Therefore, a long-range capital

improvement plan aimed at eliminating the substandard conditions

present in KCMSD schools is properly a desegregation expense and

is crucial to the overall success of the desegregation plan” (672 F.

Supp. at 403, Pet. App. 69a).

^"In conclusion, if the KCMSD schools underwent the limited

renovation proposed by the State, the schools would continue to be

unattractive and substandard, and would certainly serve as a

deterrent to parents considering enrolling their children in KCMSD

schools" (672 F. Supp. at 405, Pet. App. 72a).

- 38 -

increase, can ’fairly be said to be a state actor’" (Pet. at

20).

These contentions do not justify granting the writ. In

the first place, as the Court of Appeals held,

this argument advanced by the State attacks an

aspect of the court’s findings that was merely an

alternative basis for its conclusion. . . . Even

absent the findings that the State contributed to

causing the decay, the capital improvements

would still be required both to improve the

education available to the victims of segregation

as well as to attract whites to the schools.

(855 F.2d at 1305, Pet. App. 18a.) The issue fashioned

by the State thus will not be reached even if review

were granted.31 Moreover, the trial court found that the

31Similariy, the Petition refers to

the court of appeals’ attempt to match voting patterns with

the existence of "segregation"-by pointing out that voting

support fell off when the district enrollment became

majority black (Pet. App. 18a n.7) . . . .

(Pet. at 20). But the Court of Appeals, in the footnote cited by

Petitioners, explicitly noted that while ”[t]he record tends to support

these arguments . . . the district court did not base its findings of

(continued...)

- 39 -

racially discriminatory policies carried out in the KCMSD

after Brown "contributed to, if not precipitated, an

atmosphere which prevented the KCMSD from raising

the necessary funds to maintain its schools" (Pet. App.

124a),31 32 and the Court of Appeals affirmed (855 F.2d at

1305, Pet. App. 17a-18a). Review of findings concurred

in by both courts below is inappropriate under the "two-

court" rule, see supra note 18.33

31(...continued)

fact and conclusions of liability on this theory, [and] we need say no

more." The judgments below therefore do not rest, in any part,

upon the facts described in the footnote cited by Petitioners.

32Cf., e.g.. Reitman v. Mulkev. 387 U.S. 369, 373, 376

(1967)(examination of voter initiative "in terms of its ’immediate

objective,’ its ’ultimate effect’ and its ’historical context and the

conditions existing prior to its enactment’" revealed that "intent . . .

was to authorize private racial discriminations in the housing

market . . . and to create a constitutional right to discriminate on

racial grounds").

33If the State’s arguments were to be considered on their

merits, they are clearly lacking in substance. KCMSD’s electorate is

simply not a mass of individual private citizens when it exercises the

power conferred upon it by Missouri school law to determine the

level of capital expenditure in a district; its decisions in such

matters are as much state action as the electoral initiatives involved

(continued...)

- 40 -

II

The District Court’s Order Directing The

Collection, For A Limited Period Of Time, Of

Additional Property Tax Revenues Within The

KCMSD Adequate To Support The District’s

Share Of The Remedial Costs Is An Appropriate

Exercise Of Its Equitable Remedial Authority To

Effectuate The Fourteenth Amendment To The

Constitution

The discussion in the preceding section demonstrates

that the measures ordered by the district court are

necessary and appropriate to provide a complete remedy

for the unconstitutional and discriminatory actions of

KCMSD and Missouri officials, and that no issue

justifying review by this Court with respect to the goals

of those remedies is raised by Petitioners. There remain 33

33(...continued)

in Washington v. Seattle School District No. 1. 458 U.S. 457 (1982),

Hunter v. Erickson. 393 U.S. 385 (1969), and Reitman v. Mulkev.

The district court’s orders were not directed to persons who acted

as private parties, such as the "charitable and civic groups" which

declined or were unable to assist KCMSD in raising funds for

capital improvements (see August 25, 1986 Order at 3).

- 41 -

for consideration Petitioners’ contentions that the trial

judge so far departed from the appropriate exercise of

his equitable authority in directing the collection of

additional property taxes within the KCMSD as to

warrant scrutiny by this Court. Contrary to Petitioners’

plaintive assertions, we believe that the power of a

federal district court - in fashioning relief adequate to

redress Fourteenth Amendment violations — to require

local officials to increase tax collection when all other

means of assuring implementation of the remedy have

been exhausted, is unquestionable; and that the

appropriateness of its exercise in this instance is

established by the decisions of this Court.

- 42 -

A. The authority of federal courts in school

desegregation suits to require local tax levy and

collection in order to effectuate relief necessary to

vindicate Fourteenth Amendment rights was settled

in Griffin and this case fits squarely under that

ruling.

Preliminarily, we emphasize that this question is

presented in the context of admitted, protracted,

substantial violations of the Equal Protection Clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment which the district court

found to have caused substantial, continuing harm to the

education of black children in the KCMSD; and in the

context of that court’s having determined what is the

necessary and appropriate remedy to eliminate the

continuing effects of the violations. It is totally wrong to

say, as the State of Missouri does (Pet. at 27), that

neither of the courts below "made any serious inquiry

into whether the KCMSD might become unitary without

a mandatory tax increase." The district court carefully

- 43 -

shaped the remedy to be responsive to the nature and

scope of the violation and rejected the parties’

submissions that it viewed as going beyond this

parameter.34 Its conclusion, which was affirmed by the

court below, was that the remedies it was ordering were

necessary to accomplish the operation of the KCMSD

schools free from racial discrimination and its effects.35

34See supra note 5 and accompanying text; Pet. App. 96a-97a

(disapproving requested funding increase for test updates that would

be required even in absence of desegregation plan).

35In contrast, the State of Missouri appears to argue that the

district court should have curtailed the remedy - in other words,

rendered it less than fully adequate ~ to avoid the possibility that

if state law inhibitions on KCMSD’s ability to raise funds were not

modified by the state legislature (as they were not), the court might

be required to order an increase in the tax levy. (See State Pet. at

27.) The suggestion carries deference to the point of submission

and would inevitably reward recalcitrance.

The cases on which the State seeks to rely are inapposite. For

example, in New York State Association for Retarded Children v.

Carey. 631 F.2d 162, 165 (2d Cir. 1980), cited in State Pet. at 27

n.34, an alternative to requiring increased state funding -- "closfing]

the institution" -- was available because that remedy would have

relieved the plaintiffs from suffering the unconstitutional conditions

of confinement, see icL at 166 n.l (Kearse, J., concurring). See also

Rhem v. Malcolm. 507 F.2d 333, 341 & n.19 (2d Cir. 1974)(closing

(continued...)

- 44 -

Under these circumstances, the court’s authority to

impose additional property tax obligations within the

KCMSD in order to secure effectuation of the remedy

is, we suggest, unquestionable. In Griffin v. County

School Board of Prince Edward County. 377 U.S. 218

(1964), the public schools of one county within a state

had been closed to avoid the requirements of the 35

35(...continued)

institution had "crucial practical advantage . . . of not putting the

judge in the difficult position of trying to enforce a direct order to

the City to raise and allocate large sums of money" but in "a

situation where the uncofistitutionally-administered governmental

function must be kept operating in any event . . . , a court might

have no choice but to order an expensive, burdensome or

administratively inconvenient remedy"); Reece v. Gragg. 650 F.

Supp. 1297, 1307-11 (D. Kan. 1986)(setting jail population ceilings

as condition for staying injunction against continued operation of

facility pending submission and implementation of plan to correct

unconstitutional conditions), cited in Clark Pet. at 22 n.6.

Such an approach is not feasible in a school desegregation

action. Enjoining the operation of the KCMSD schools until the

remedy were implemented would cause further harm to the victims

of the constitutional violations. Enjoining all public schooling in

the KCMSD suburbs, or throughout Missouri, until the plan were

funded, would similarly penalize the victims of segregation as well

as be a gross departure from equitable principles.

- 45 -

Fourteenth Amendment as interpreted by this Court in

Brown, cutting off the opportunity for black pupils within

the county to be educated. White pupils were assisted

by county authorities to continue their schooling through

a program of tuition grants for private school attendance

and tax exemptions and credits. This Court held that

the scheme violated the Fourteenth Amendment.

In its opinion, this Court explicitly outlined "the kind

of decree necessary and appropriate to put an end to

the racial discrimination practiced against the[ black

children] under authority of the Virginia laws." Id. at

232. The district court had enjoined payment of the

tuition grants or allowance of the tax exemptions so long

as the public schools remained shut, and this Court had

"no doubt of the power of the court to give this relief to

enforce the discontinuance of the county’s racially

- 46 -

discriminatory practices," Jd. at 232-33. But this Court

went further to describe the broad affirmative, remedial

authority of the trial courts in desegregation cases:

The injunction against paying tuition grants and

giving tax credits while public schools remain

closed is appropriate and necessary since those

grants and tax credits have been essential parts of

the county’s program, successful thus far, to

deprive petitioners of the same advantages of a

public school education enjoyed by children in

every other part of Virginia. For the same

reasons the District Court may, if necessary to

prevent further racial discrimination, require the

Supervisors to exercise the power that is theirs to

lew taxes to raise funds adequate to reopen,

operate. and maintain without racial

discrimination a public school system in Prince

Edward County like that operated in other

counties in Virginia.

(Id. at 233 [footnote omitted and emphasis added].)

The district court had stated it would consider (but had

not yet issued) an order to accomplish the reopening of

the schools. This Court remanded with instructions to

enter the sort of decree it had described:

- 47 -

An order of this kind is within the court’s power

if required to assure these petitioners that their

constitutional rights will no longer be denied

them. The time for mere "deliberate speed" has

run out, and that phrase can no longer justify

denying these Prince Edward County school

children their constitutional rights to an education

equal to that afforded by the public schools in

other parts of Virginia.

. . . [T]he cause is remanded to the District

Court with directions to enter a decree which will

guarantee that these petitioners will get the kind

of education that is given in the State’s public

schools. And, if it becomes necessary to add new

parties to accomplish this end, the District Court

is free to do so.

(Id. at 233-34 [emphasis added].)36

^Because the Court remanded with instructions to enter such

a decree, Petitioners err fundamentally in trying to discount the

importance of the Court’s opinion because "the Court did not itself

order a tax levy increase" (Clark Pet. at 18; see Jackson County Pet.

at 10) or "no tax was actually before the Court in Griffin" (State

Pet. at 24). The direction to add parties, if required,

unquestionably refers to the County Board of Supervisors, and the

necessity of joining them as parties quite evidently refers to the task

of assuring funding adequate to "guarantee" that black students in

the county would receive "the kind of education that is given in the

state’s public schools" "without racial discrimination."

- 48 -

(continued...)

The trial court here has faithfully applied the

precepts of Griffin. It first considered and approved a

remedy adequate to assure the operation of the KCMSD

schools without racial discrimination. It carefully

determined what resources would be required to

implement that remedy and allocated the costs between

the joint tortfeasors, the State of Missouri and KCMSD.

It required the KCMSD to attempt through every means

at its disposal to raise its share of the necessary funding,

including by seeking voter approval for additional tax

levies on four occasions in 1986 and 1987.* 37 To meet

KCMSD’s fiscal obligations in the early stages of plan

^(...continued)

As is evident from the passages quoted in the text, Missouri

also is wrong in suggesting that the Court’s discussion in Griffin

"was limited to a single conclusory statement" (id.).

37See 672 F. Supp. at 411, Pet. App. 85a-86a (summarizing

attempts by KCMSD to raise funds as well as failure of Missouri

legislature to provide new mechanism for this purpose); Pet. App.