Memo from Camerino to Williams

Correspondence

April 13, 1982

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Memo from Camerino to Williams, 1982. 351d75a4-de92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c863777d-970b-4622-b8a7-6edc7d49f1e7/memo-from-camerino-to-williams. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

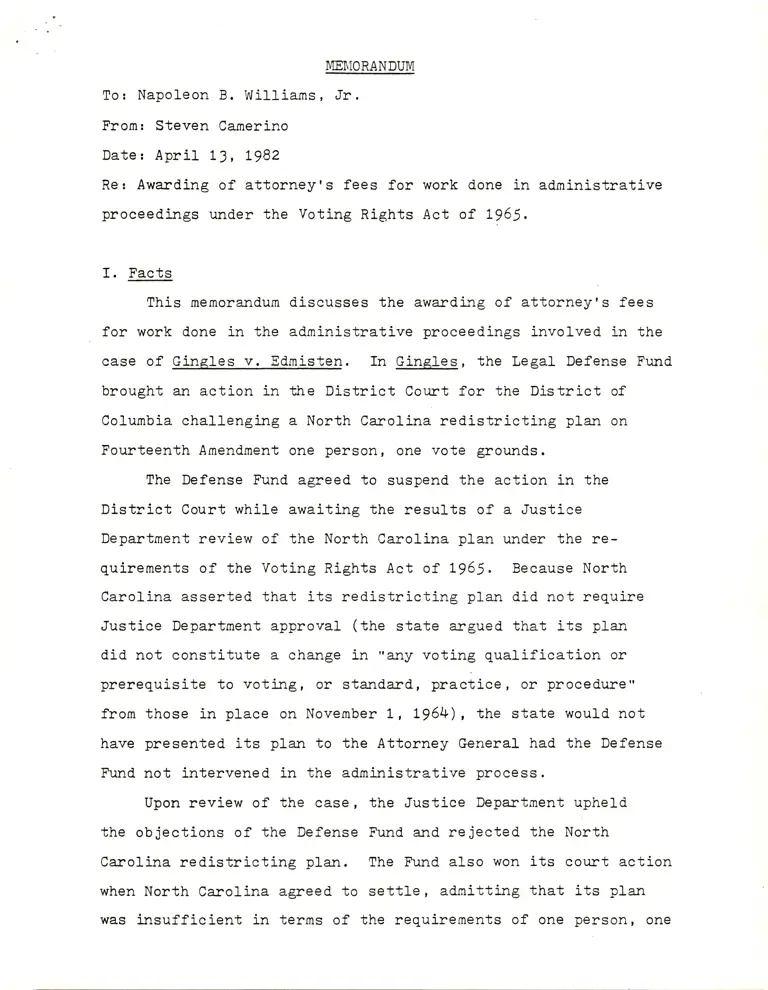

MEMORANDUM

To: Napoleon B. Williams, Jr.

From: Steven Camerino

Date: April 13, 1982

Re: Awarding of attorney's fees for work done in administrative

proceedings under the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

1-1193

This memorandum discusses the awarding of attorney's fees

. for work done in the administrative proceedings involved in the

case of Gingles v. Edmisten. In Gingle , the Legal Defense Fund

brought an action in the District Court for the District of

Columbia challenging a North Carolina redistricting plan on

Fourteenth Amendment one person, one vote grounds.

The Defense Fund agreed to suspend the action in the

District Court while awaiting the results of a Justice

Department review of the North Carolina plan under the re-

quirements of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Because North

Carolina asserted that its redistricting plan did not require

Justice Department approval (the state argued that its plan

did not constitute a change in "any voting qualification or

prerequisite to voting, or standard, practice, or procedure"

from those in place on November 1, 1964), the state would not

have presented its plan to the Attorney General had the Defense

Fund not intervened in the administrative process.

Upon review of the case, the Justice Department upheld

the objections of the Defense Fund and rejected the North

Carolina redistricting plan. The Fund also won its court action

when North Carolina agreed to settle, admitting that its plan

was insufficient in terms of the requirements of one person, one

vote.

II. Question Presented

Can the Legal Defense Fund recover attorney's fees for

work done in the administrative part of the proceedings in

Gingles v. Edmisten?

III. Answer

The Voting Rights Act of 1965, as amended in 1975,

provides for attorney's fees in "any action or proceeding

to enforce the voting rights guarantees of the fourteenth

or fifteenth amendment". Although this provision is subject

to the court's discretion, it is now accepted that,.barring

special circumstances, such fees will be awarded to the pre-

vailing party.

IV. Statutes

Attorney's Fee Provisions-—

Section 402 of the 1975 amendments to the Voting Rights Act

of 1965—-42 U.S.C. §19731(e) (1976):

"In any action or proceeding to enforce the voting rights

guarantees of the fourteenth or fifteenth amendment, the court,

in its discretion, may allow the prevailing party, other than

the United States, a reasonable attorney's fee as part of the

costs."

Section 706(k) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964--42 U.S.C.

EZOOOe-5(k) (1976):

"In any action or proceeding under this subchapter the

court, in its discretion, may allow the prevailing party,

other than the Commission or the United States, a reasonable

attorney's fee as part of the costs, and the Commission and

the United States shall be liable for costs the same as a

private person."

-3-

Section 209(b) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964--42 U.S.C.

§2000a—3(b) (1976):

"In any action commenced pursuant to this subchapter, the

court, in its discretion, may allow the prevailing party, other

than the United States a reasonable attorney's fee as part of

the costs, and the United States shall be liable for costs the

same as a private person."

Voting Plan Preclearance Statute--

Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965--42 U.S.C. §1973c=

"Whenever a State or political subdivision...shall seek to

andminister any voting qualification or prerequisite to voting,

or standard, practice, or procedure with respect to voting

different from that in force or effect on November 1, 1964...

such State or subdivision may institute an action in the United

States District Court for the District of Columbia for a de—

claratory judgment that such qualification [:7 prerequisite,

standard, practice, or procedure does not have the purpose and

will not have the effect of denying or abridging the right to

vote on account of race or color...Provided, that such qualifi-

cation, prerequisite, standard, practice, or procedure may be

enforced without such proceeding if [it7 has been submitted...

to the Attorney General and the Attorney General has not inter—

posed an objection within sixty days after such submission...."

V. Discussion

The problem of whether the attorney's fee provision of the

Voting Rights Act of 19651 was intended to provide for an award

of fees for work done for administrative proceedings is best

answered by looking at the specific wording of the section and

by reviewing the courts' interpretation of a similar attorney's

fee provision included in Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of

19642. The reports of both the House and Senate Judiciary

Committees on the 1975 amendments to the Voting Rights Act of

1965 make it clear that E1973l(e) was intended to authorize the

awarding of attorney's fees for both administrative proceedings

and court actions and that the provision is to be interpreted

in the same manner as the attorney's fee provisions of the

1964 Civil Rights Act.

A. What are the Title VII standards?

The attorney's fee provision in the Voting Rights Act is,

according to both the Senate and House committee reports on the

1975 amendments to the Act, "intended to be similar to provisions

in Titles II and VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964...."

S. Rep. No. 295, 94th Cong., 1st Sess. 40 (1975). Other than

the explicit wording to that effect, probably the strongest

evidence that the Congress intended §19731(e) of the Voting

Rights Act to be interpreted in the same manner as §706(k) of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964 is that the two provisions contain

precisely the same operative wording. Furthermore, the stan-

dards for awarding fees under the two provisions should be

similar as well. id.

1 42 U.S.C. a19731(e).

2 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(k) (1976).

-5-

A party seeking to enforce the rights protected by the

Constitutional clause or statute under which fees are

authorized by these sections, if successful, "should or-

dinarily recover an attorney's fee unless Special circum-

stances would render such an award unjust." Newman v.

Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc....390 U.S. 400, 402 (I968).

id. Because the legislative history of €1973l(e) makes it

clear that judicial interpretation of the Civil Rights Act

attorney's fee provisions is pertinent to an understanding of

§1973l(e) itself, it will be useful to look first to how the

courts have dealt with the Title VII and Title II provisions.

In examining the use of the words "In any action or

proceeding..." in §706(k) of the Civil Rights Act, the Supreme

Court in New York Gaslight ClubJ Inc. v. Carey, 447 U.S. 54

(1980) noted that the chosen wording was clearly meant to in-

clude an awarding of attorney's fees for work done in adminis-

trative proceedings. 447 U.S. at 61. The Court commented that

the use of the word "or proceeding" was not mere surplussage

and that the Congress had.intended to distinguish between court

"actions" and administrative "proceedings".

Congress' use of the broadly inclusive disjunctive phrase

"action or proceeding" indicates an intent to subject the

losing party to an award of attorney's fees and costs

that includes expenses incurred for administrative pro-

ceedings.

id. The Court further noted that "throughout Title VII the

word 'proceeding,' or its plural form, is used to refer to all

the different types of proceedings in which the statute is en—

forced, state and federal, administrative and judicial." 447

U.S. at 63.

In Parker v. Califano, 561 F.2d 320 (D.C. Cir. 1977),

the Circuit Court for the District of Columbia also addressed

the question of attorney's fees for work done in Title VII

-6-

administrative proceedings and analyzed the problem in a

manner quite similar to the Supreme Court's approach in Ngw

York Gaslight. In Parker, the court noted the use of the dis-

junctive "or" between the words "action" and "proceeding", as

did the Supreme Court in New York Gaslight, and cited "the

familiar principle that statutory language should be con-

strued so as to avoid redundancy." 561 F.2d at 325. The

court then went on to say that

Had Congress wished to restrict an award of an attorney's

fee to only suits filed in court, there would have been

no need to add the words "or proceeding" to "any action."

But "proceeding" is a broader term than "action" and

would include an administrative as well as judicial

proceeding. Johnson v. United States, D.Md. Civil Action

No. H—74—13434(June 8, 1976).

id. The court also noted that since Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964 required that an administrative proceeding

take place before a complainant could file a court action, the

wording of the attorney's fee provision of the subchapter

strongly suggested that the Congress had no intention of

limiting the awarding of fees to work done in a court action.

561 F.2d at 324.

In Gingle , strictly speaking, the statute did not

require an administrative proceeding. However, since the

statute did require North Carolina to seek a declaratory

judgment approving the redistricting plan if it did not seek

approval by the Attorney General. The Legal Defense Fund

thus had the option of seeking the enforcement of the statute

by resort to the Attorney General or the courts. As is

explained in the sec¢ions below, the Defense Fund's choice

of forum does not appear to affect the outcome of the at-

torney's fee issue, since the awarding of fees turns on the

-7-

wording of the statute and the policies which the statute

reflects.

As noted above in the excerpt from the Senate Judiciary

Committee report on the 1975 amendments to the Voting Rights

Act of 1965, the attorney's fee provision of the Act is meant

to incorporate the standard for awarding fees that was set in

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S. 400 (1968).

One writer has commented that

P'ggie Park broadened the permissible scope of fee

granting by interpreting a discretionary provision for

attorney's fees as a virtual command always to award

fees to a successful plaintiff....More importantly, the

decision also revealed that the Court...regarded the

award of fees...as an effective way of encouraging

"private attorneys general" to bring lawsuits that ad-

vance the public interest.

Nussbaum,’Attorney's Fees in Public Interest Litigation,"

48 N.Y.U.L.Rev. 301, 319-320 (1973). As a result of Piggie

Park, it has now become the rule that barring special cir-

cumstances, a successful Title VII plaintiff should receive

an award of attorney's fees. Newman v. Piggie Park, 390 U.S.

at 401—02; Alyeska Pipeline Co. v. Wilderness Society, 421

U.S. 240, 262 (1974). The House3 and Senate“ committee

reports on the 1975 amendments both explicitly adopted this

interpretation for the attorney's fee provision. In Parker,

561 F.2d 320, the Circuit Courtused the stnngest language

so far in referring to the holding of Piggie Park, noting

that "failure to award attorney's fees to a prevailing party

in a Title VII action has been held an abuse of the District

Court's discretion. Lea v. Cone Mills Corp., 438 F.2d at 88."

561 F. 2d at 331.

B. A comparison 9: Title ii and Title VII 9; the Civil Rights

gfiiRt‘Repi-No. 195, 94th Cong., 1st Sess. 34 (1975).

48.Rep. No. 295, 94th Cong., 1st Sess. 40 (1975)

Act 2i 1964.

Possibly the.most useful way to analyze the attorney's fee

provision of the Voting Rights Act is to examine what it does

not say. As previously noted, the legislative history of the

provision makes it apparent that the attorney's fee portion of

the Act is to be interpreted in the same manner as that of

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Many of the cases

interpreting the attorney's fee provision of Title VII have

found a comparison with the fee provision of Title II useful.

This is because, in contrast to Title VII, which like E1973l(e)

of the Voting Rights Act refers to "any action or proceeding,"

Title II refers only to "any action." The reason for this dif-

ference is readily apparent upon examination of the provisions

of Title II, they dealoonly with court actions and make no

mention of administrative proceedings. Parker, 561 F.2d at

328. In Parker, the court commented that

we find particularly instructive a comparison of the

language of the attorney fee provision of Title VII...

with that of the attorney fee provision of Title II...

of the Civil Rights Act. of 1964. The provisions were

enacted contemporaneously in 1964 as part of the Act.

The language of the two subsections is identical except

that, where Section 706(k) refers to "any action or pro—

ceeding under this subchapter," Section 204(b) refers

simply to "an action commenced pursuant to this sub—

chapter." (3%phasis added.) This material difference

is understandable only in light of the fact that the

enforcement scheme of Title II is solely judicial...,

while the enforcement scheme of Title VII is both ad-

ministrative and judicial....The inclusion in Section

706(k) of the reference to "proceeding"--in addition

to "action"--appears to be clear manifestation of

Congress' intent that the attorney fee provision should

apply to both aspects of the Title VII enforcement

scheme.

at.

In Kennedy V. Whitehurst, 25 EPD 931,704 (D.D.C. 1981),

the District Court ruled that no attorney's fees were to be

-9-

awarded for work done on the administrative level in a case

brought under the Age and Discrimination in Employment Act

(ADEA), 29 U.S.C. @221 22 dgq. In that case, the language of

the attorney's fee provision involved was confiderably more

restrictive than the language of the attorney's fee provision

of Title VII which was interpreted in New York Gaslight. In

Kennedy, the provision referred only to "court", "action",

"plaintiff", and "judgment". The court insisted that, cone

trary to Title VII as shown in New York Gaslight, the ADEA

provision was meant to apply to a court action only. The

court found the provision comparable to that of Title II, not

that of Title VII, of the 1964 Act. Kennedy, 25 EPD fl31,704

at 20,067. The court further noted that in Kennedy the re—

sort to an administrative proceeding was optional, not man-

datory as it was in Title VII. Thus an administrative pro-

ceeding was not an obstacle here to the vindication of the

plaintiff's rights. id. at 20,068. Instead, the administra—

tive proceeding in Kennedy mainly served the purpose of giving

notice to the defendant. The court noted that a layman was

capable of carrying out this part of the complaint process

without the aid of an attorney. In New York Gaslight on the

other hand, the administrative proceeding was necessarily ad-

versarial in nature and was used in order to create a record

for the litigation. id.

The court in Kennedy also noted the ADEA's lack of speci-

fic statutory authorization for the awarding of attorney's

fees, the optional and notice giving nature of the administra-

tive proceedings, and the fact that full relief was afforded at

the administrative level without the need for judicial inter-

-10-

vention as factors leading to its decision.

None of these factors can be said to be truly present

in Gingles. There is, for example, specific statutory authori-

zation for the awarding of fees. The administrative proceedings

were not at all of a notice giving nature since they could

be used to satisfy the approval requirements of the statute.

Nor were the proceedings optional, except in the sense that any

change in voting procedures required approval by the Attorney

General or the District Court for the District of Columbia.

They were not optional in the sense that approval of a voting

plan was not mandatory, though. Lastly, although full relief,

at least for the time being, was achieved at the administrative

level, this was only because North Carolina agreed to settle

the District Court case against it when it agreed to acknowledge

that its plan was constitutionally insufficient. This last

factor is particularly important in light of the Senate Judiciary

Committee report's comments on the attorney's fee provision and

the concept of "prevailing party" as intended in that provision.

[F7or purposes of the award of counsel fees, parties

may be considered to have prevailed when they vindicate

rights through a consent judgment or without formally

obtaining relief.

S. Rep. No. 295, 94th Cong., lst Sess. 41 (1975). Also, Title

VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 has been interpreted as

permitting the awarding of attorney's fees "to a party who

prevails in his complaint of discrimination at the administra-

tive level and who receives there the complete relief requested."

Smith v. Califano, 446 F.Supp. 530, 531 (D.D.C. 1978). It

should be noted, however, that in New York Gaslight Justice

Stevens in a concurring opinion specifically excepted this issue

-11-

from the Court's ruling.

A quite different question would be presented if, before

any federal litigation were commenced, an aggrieved party

had obtained complete relief in the administrative pro-

ceedings. It is by no means clear that the statute, which

merely empowers a "court" to award fees, would authorize

a fee allowance when there is no need for litigation in

the federal court to resolve the merits of the underlying

dispute.

447 U.S. at 72. Still, it would appear that no similar issue

would arise under the Voting Rights Act since a plaintiff

could simply bring a court action instead of an administrative

proceeding if it desired to challenge a states voting pro-

cedures. The plaintiff could thus win an award of attorney’s

fees in addition to a favorable judgment. To so encourage a

plaintiff, though, would run contrary to the policy of not

overloading our courts. Thus the attorney's fee provision,

at least in the Voting Rights Act, would probably not be

interpreted as requiring that the plaintiff have brought a

court action in order to collect attorney's fees for any work

done at the administrative level. In any case, in Gingles

the Defense Fund did bring a court action and only held off

on litigating the action while waiting for the results of

the administrative proceedings.

C. Consequences 9i not giving attorney's fees 39 g plaintiff

who has been successful gi the administrative level.

In addition to the statutory interpretation argument which

the courts have used in interpreting the attorney's fee pro-

vision of Title VII, the courts have applied policy arguments

to support the rule that attorney's fees should be awarded for

work done at the administrative level. As with the statutory

interpretation argument, these policy arguments can be applied

-12-

in full to the Voting Rights Act's attorney's fee provision.

The courts have generally noted that in writing the attorney's

fee provision of Title VII Congress intended to encourage the

enforcement of the statute through the bringing of meritorious

claims by private attorneys general. In New York Gaslight,

the Supreme Court observed that

It is clear that Congress intended to facilitate the

bringing of discrimination complaints. Permitting an

attorney's fee award to one in respondent's situation

furthers this goal, while a contrary rule would force

the complainant to bear the costs of mandatory state and

local proceedings and thereby would inhibit the enforce—

ment of a meritorious discrimination claim.

447 U.S. at 63. Particularly in cases such as those brought

under the Votinngights Act, it is important to encourage the

bringing of meritorious claims since neither compensatory nor

punitive damages are available. Furthermore, as the Court

observed in New York Gaslight, the awarding of fees helps to en-

sure the "incorporation of state [here, administrative_7 pro-

cedures as a meaningful part of the Title VII [here, Voting

Right§7 enforcement scheme." id. at 65. Awarding attorney's

fees only for work done in.a court action would discourage the

complainant from fighting a complete and vigorous battle at the

administrative level and would encourage him or her instead to

wait for a chance to litigate the issue in court. The Circuit

Court in Parker v. Califano argued that such a result would

work against the goals of discovery of evidence while it is

still fresh, a full develpoment of the administrative record,

and judicial economy.

In addition to being inconsistent with the recognized

policies of Title VII, the distinction between attorney's

fees for services at the administrative and judicial

levels is inconsistent with the realities of legal

-13-

practice. For a conscientious lawyer representing a

federal employee in a Title VII claim, work done at the

administrative level is an integral part of the work

necessary at the judicial level. Most obviously an

attorney can investigate the facts of his case at a time

when investigation will be most productive. The attorney

may thus gain the familiarity with the facts of the case

that is so important in the fact-intensive area of em—

ployment discrimination. Perhaps even more important,

the administrative proceedings allow the attorney to

help make a record that can be introduced at any sub—

sequent District Court trial. Especially in an instance

where development of a thorough administrative record

results in an abbreviated but successful trial, refusing

to award attorneys' fees for work at the administrative

level would penalize the lawyer for his pre—trial effec—

tiveness and his resultant conservation of judicial time.

561 F.2d at 333.

In its committee report on the 1975 amendments to the

Voting Rights Act, the Senate made similar findings. The

committee found that fee awards are essential to the full

enforcement of the requirements of the Constitution and the

Act and that "the effects of such fee awards are ancillary and

incident to securing compliance with these laws, and that fee

awardshre an integral part of the remedies necessary to ob-

tain such compliance." S. Rep. No. 295, 94th Cong., 1st Sess.

41 (1975).

D. Role 2: attorney's fees in encouraging the bringing 9i

complaints by private attorneys general.

A dominant theme in cases interpreting the attorney's fee

provision of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 is that

the provision was intended to encourage the bringing of suits

by private attorneys general in order to enforce the Act.

After noting that the attorney's fee provision in the Voting

Rights Act is similar to the provisions in Titles II and VII

of the Civil Rights Act, the Senate Judiciary Committee report

states that

-14-

Such a provision is appropriate in voting rights cases

because...Congress depends heavily upon private citi—

zens to enforce the fundamental rights involved. Fee

awards are a necessary means of enabling private citi—

zens to vindicate these Federal rights.

id. at 40. In New York Gaslight, the Supreme Court said that

"Congress has cast the Title VII plaintiff in the role of

l'a private attorney general,‘ vindicating a policy 'of the

highest priority'....[Christiansburg Garment Co. v. EEOC,

434 U.S. 412, 420 (1978);7" 447 U.S. at 63.

The Court also reiterated in New York Gaslight that not

only should attorney's fees be awarded in all cases under the

Title VII standard absent special circumstances 5, but.also

that "representation by a public interest group is [not7 a

'special circumstance' that should result in denial of

counsel fees." id. at 70 n. 9. Thus the Supreme Court gave

its approval, albeit in dictum, to a number of circuit court

rulings6 such as the one by the First Circuit in 19787 in

which the court awarded the Legal Defense Fund attorney's fees

in a Title VII case after the District Court had awarded fees

to the plaintiff's private counsel only. In that case, the

Circuit Court said that

Attorney's fees are, of course, to be awarded to attorneys

employed by a public interest firm or organization on

the same basis as to a private practitioner."

Reynolds v. Coomey, 567 F.2d 1166, 1167 (1st Cir. 1978).

In an earlier decision by the Second Circuit, Torres v. Sachs,

538 F.2d 10 (1976), a similar conclusion was reached. The

court in Torres noted that

5447 U.S. at 68.

6Torres v. Sachs. 538 F.2d 10 (2d Cir. 1976); ngrley v. .

Patterson, 493 F.2d 598 (5th Cir. 1974); Jordan v. Fusarl,

596 F.2d 646 (2d Cir. 1974).

7Reynolds v. Coomey, 567 F.2d 1166 (1st Cir. 1978).

-15_

Litigation to secure the law's protection has fre—

quently depended on the exertions of organizations

dedicated to the enforcanat of the Civil Rights Acts....

We agree with the courts which have held that the

"allowable fees and expenses may not be reduced because

(the prevailing party's) attorney was employed...by a

civil rights organization...or because the attorney

does not exact a fee." Fairley v. Patterson, 493 F.2d

598, 606 (5th Cir. 1974)....

538 Féad at m3.: 1$he Teourt sreachedets.conolusicn,thatar

representation by a civil rights organization should not lead

to a reduction in the fees awarded after noting that the legis—

lative history of the statute makes "it quite plain that the

Congress rejected any such limitation." id. at 12. The

court also argued that such a conclusion was supported by the

consideration that "such voting rights enforcement by liti-

gation, in common with other similar essential minority civil

rights enforcement, is to be encouraged by reasonable fee awards

rather than discouraged by requiring successful plaintiffs to

bear litigation costs." id. Thus the fact that the Legal

Defense Fund is a non-profit organization and did not charge

for its services in the Gingles case doesnot appear towbe

grounds for a denial of attorney's fees.

E. Consequences 9i not awarding attorney's fees for work done

d: the administrative level.

Both the applicable case law and the legislative history

of §l973l(e) make it clear that Congress intended "to accord

parallel or overlapping remedies against discrimination [in

the area of civil rightsi7" Parker, 561 F.2d at 328. "Con—

sistent with this view Title VII provides for consideration

of employment-discrimination claims in several forums." id.

In Parker, the District of Columbia Circuit Court went on to

say that

—16—

The instant case, in fact, is representative of the

operation of the integrated enforcement scheme created

by Congress. Because of the structure of Title VII en-

forcement procedures, the administrative and judicial

proceedings in this case as in Johnson v. United States,

554 F.2d 632 (4th Cir. 197717 "were part and parcel of

he same litigation for which an attorney's fee is now

sought." 554 F.2d at 633.

561 F.2d at 329.

In Smith v. Califano, 446 F.Supp. 530 (D.D.C. 1978), the

District Court discussed the consequences of not treating the

administrative and judicial levels of the.enforcement scheme

of Title VII equally with regard to the awarding of attorney's

fees. The court noted that awarding attorney's fees in court

but not in administrative proceedings would lead to the

plaintiff's perceiving his claim as being not worth vindicating,

at least at the administrative level. At best, such a policy

would lead the plaintiff to hope that his claim was only good

enough to win in court, but not so good as to lead to vic—

tory at the administrative level. id. at 534. Thus in an

enforcement scheme where the administrative procedure was not

mandatory or was merely perfunctory, the plaintiff would be

encouraged to take his claim to court so that he could both

vindicate his rights and win an award of attorney's fees.

Such a policy would greatly diminish the utility of administra-

tive proceedings. The result of not awarding attorney's fees

would thus be to relegate the administrative level of the

complaint procedure to a mere pig £2223 status. "It might

also mean that the administrative record, which can be admitted

as evidence in court would be less complete and thus of less

assistance in conserving the courts' time in suits that are

filed." id. For this reason, as noted above, a strong argu-

ment could be made in the Gingles case that were the court

_17_

not to award attorney's fees for work done at the adminis-

trative level, it would be encouraging practices inimical

to policies which have traditionally been considered to be

among those most important to a fair and efficient system

of justice.

F. Conclusion

It appears that the case law and the legislative his—

tory both heavily argue in favor of the court's granting

attorney's fees in Gingles. The only apparent obstacle to

such a ruling is the question as to whether the administra-

tive proceedings in Gingles were "optional" and whether full

relief was granted at the administrative level without

judicial intervention. These problems are minimized,

however, when one considers the fact that North Carolina

would never have submitted its plan for approval had the

Defense Fund not brought its action.