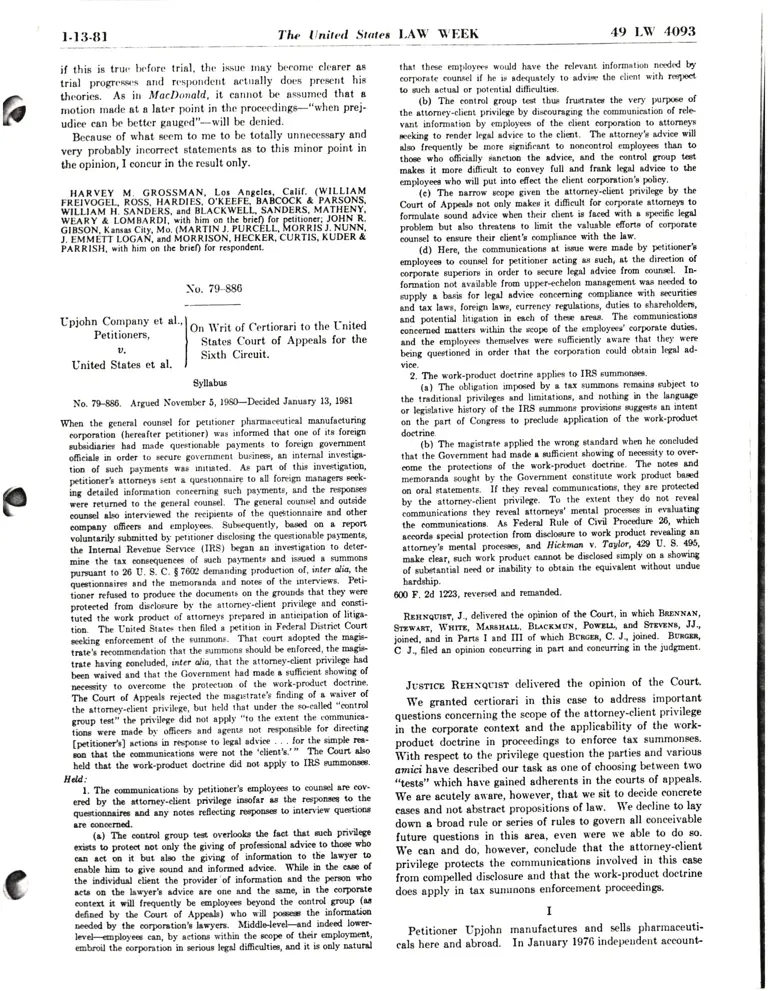

Upjohn Company et. al. Petitioners v. United States et. al. Syllabus (United States Law Week)

Press

January 13, 1981

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Upjohn Company et. al. Petitioners v. United States et. al. Syllabus (United States Law Week), 1981. a84adec5-db92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c869a4fa-3092-4a72-bcd4-b695ad9fc682/upjohn-company-et-al-petitioners-v-united-states-et-al-syllabus-united-states-law-week. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

l-t:t-81 T'lu, ltnitetl Stotet l,AW T'EEK 49 L\t', 4093

if this is trttt lx'fonr trial, tht'issuc lttrry bt'eontt'elt'arer as

trial prr.rgrt'sx's otrd rcspotrrictrt nrtrrally dtx's preacrrt his

theories. Ae in ltlacDonald, il cartttot bt assumcd that a

nrotion tnatlc at a latlr point in the proccodings-"whcn prej-

udict' ean be bettrr gauged"-u'ill be dcnied.

Bceause of what seem to me to bc totally unttecessary and

very probably incorrcet statenrcnts as to thie minor point in

the opinion, I concur in the rcsult only.

HARvEY M. GROSSMAN, Loe Ansclo, Calif' (WILLIAM

rRErvoGEL. ROSS. HARDIES, O'XEEFE,-BABCqCT & PARSONS,

wi[Ltru x. sexorns, and BLACKWELL, SANDERS' MAIIIE|II'

*LAii a Lot{senol,'with him on thc bricf) for pctitioncr; ryryN--!.

clsSoN. Kanses Citv. Mo. (MARTIN J. PURCELL, MORRIS J. NUNN.

J. pMMiTr locet(. and MoRnlsoN, HECKER, cURTIS' KUDER &

PARRISH, with him on thc bricf) for rcspondcnt.

\o. 79-886

that tht:sc emtrloyft'r wou.ld have the rclevant informatiotr netdtd by

corfrcrltr counnel if he is adequately to adviee the clienl with rcrslrct

to such Bctual or potcntia.l dilficultics.

(b) The control group tr:st tbru frustrsteE the very purgreo of

the attorney-client priviltAe by discouraging the communication of rele

vant informetion by employet* of the client corporstion 10 sttornelt

ceking to render legal advice to the elient. The attorncyt advice will

also frequently be more eiSnifeant, to noncontrol employees thsn to

thae who officially sancttoo the advice, and the control group teet

makes it more diJficult to convey full end fraok legal advico to the

employeee who will put into effoct the client corporstion's poliry.-

(c) me Derrow scopo given tho &ttorney-clieDt privilege by the

Court of Appeale rot only makee it difficuli for corporat€ attorneyt to

forrnulete eound advice wben thcir clieat ie faced with o rpeeiEc legal

problem but also thresteDt to limit the vsluable efrorte of corporEte

couneel to engure their client'e compliance with the lew'

(d) Here, the communications at issue were made by petitioner'e

employeea to couneel for petitioner aeting as such; at the direction of

corporate superiora in order to seure legal advice from cound' In-

formation no1 available from uppcr-echelon managemmt waa needed to

supply a basis for legal advic conceraing compliance with eecuritieg

and tax la*., foreign lawe, eurreney reguletions, dutic's to ehareholders,

end potentiel litigation in each of the* areas' The communications

concemod Estter within the scope of the employees' corporate dutiea'

end the employe<r thenuelves were suf6ciently aware thot thel' were

being questioned in order that the eorporation eould obtain lec&l 8d-

vice.

2. The work-product doctrine applies to IR^S summonsee'

(a) The obligation imf,G€d by & t8r suuuDons rtmaina subject to

the trsditioDsl privileges and lirnitetione, and nothing in the languagp

or legislative hisrory of the IRS 8uuiluon8 provisions $88est6 sn inteJot

on tf,e part of Congress to preclude application of the work-product

doctrine.

(b) The magistrate applied the wrong etandard whm he concluded

that ihe Government had made r mfficient ehowing of necessity to over-

eome the protections of the work-product' doctrine' .The notee end

.".ot*a" sought by the Government constitut€ work product baed

on oral statemenrt. lf th"y reveal communtcations, they are protected

by the attornqv-elient privilege. To the extent they do not reveal

communicetions they reveal aitorneya' mental processes in evaluating

it. i*.uni.rtiona. Ae Federal Rule of Civil Proeedure 21, vhieh

a"corde.peciat protection from diecloeure to work product' revealiog au

attorne-r"s mm;l processes, rrr,d, Hickma v' T1ubr, 4g) U' S' 495'

.rLu .i*r, such work pnr,cluct cannot be disclo'ted sioply on a ehowing

"f.rkt"riUf

need or inability to obtsi! the equivalent without undue

hardahip.

000 f. 2d 1223, reversed end rerosnded'

Rsxxeuler, J., delivered the opinion of the Court, in whieh BnoNxer'r,

Srzw^at, lYxrrz, I\{enexrlr, Blrcxvux, Powrr.r', and 9rrwxs, JJ',

joined, and in Parts I and III of which Bt'ncnn, C' J', joined' Buncrn,

b f., nfua an opinion concurring in pert end concurring in the judgroeut'

Jusrrcp RBssqrtsr delivered the opinion of the Court'

IVe granted certiorsri in thia ease to address important

questiois concerniug the scope of the attorney-client privilege

in the eorporate eontext snd the applicability of the work-

product doctrine in proceedings to enforce tgx summonsee'

iYith respect to the privilege question the parties and various

ornici have described our tssk as one of choosing between two

"tegts" uhich have gained adherentE in the eourts of appeals'

We are scutely a$'are, however, that we sit to decide eonerete

ceses &nd not abstrs4t propositions of law' 1\'e decline to lay

dowr a broad rule or series of rulee to govern all conceivable

future questions in this 8re8' even $'ere te able to do so'

E'e can and do, however, conclude that the attorlrey-client

privilege prot€cts the communicationo involved iu this csse

iror, cinrlrelled tlisclosure slld that the work-product doctrine

does apply in tax sutlunons euforcement proceedingt'

I

Petitioner Upjohn manufactures and sells phartnaceuti-

eals here and abroad' In Jenuary 1976 indeperrdent aceount'

L'pjohn cornpany et al"

I on \\'rit of certiorari to the f nitedPetitioners, l" S;;; i:or.i "f ,llrpual. for rheu' I si*tt Circuit.

Unitcd States et al. t

Syllabu

No. 79-888. Argued November 5, lgEG-Decided January 13, l98l

When the general counsel for petliioner pharmaceutical manufacturing

corporetio; (hereafter petitioner) wus informed that one of its foreign

eubsidiaries had mnde queslionable ps)'ments to foreign govemment

officiale in onder to s€cure govcmmcnt business, al intcrnal invxtig&-

lion of sueh pa)'ments was utttieted. As pan of this investigation,

petitionert attornele sent a quostlornaire to all fortigo rurugem seek-

Lg detailed inforsutron concerning sueh palments, and the responses

wJre raurned ro rhe general counsel. The general c'ounsel and outside

counsel eloo inten'iewed the recipiente of the quetionnairc and other

comperiy officers and employat. Subr:equently, baeed on s Eport

volurtarily zubmitred by petitioner disclosing the quenionable pa]melts,

tlre Interoal Rcvehue Servrce (IRS) began an investigation to det€r'

mine the tax consequences of sucb palments ard issued a summoDs

pursunt to 26 U. S, C. $ 76OJ deuurtding producrion of , intet oira, the

iucrrionnaires and the memoranda and notes of the urten'iews' Peti-

tioner refused to produee the documents on the gtouuds th8t they were

protected frosr dlclozurc b1' the artornel'elient privilege and consti-

iuted the worl product of artorneys prepared in anticipation of litiga-

tiou. The United Stares then filed I petilion in Federal District Court

*eking enforcemeni of the Fulrunons. Thar coun adopred the magis-

tot"'.-r".o..*tlationlhatthesummonsshouldbeenforeed,themagi+

true having concluded, inter olia, rhat the sttorney-client privilege had

bcea waivJ and that the Government had made e sufficient showing of

*a.oiay to overcome the protectloD of the *'ork-product doctrine'

The Court of Appeals rejected the magrstrBte's finding of s waiver of

ihe ettomey-clieni privilege, but held that under the socslled "control

g;up t."t'; tl,. p;i'itege did not applv "to the extent the communica-

ii*"- *"t maae U1' officens and sgenlc not responsible for directing

[petitione/e] sclions iD r6?onse to legol advite ' '.lor the simple rea-

il tLt the communicationr were not the 'client'e'"' The Court Elso

held thlt the work-product doctrire did not apply to IRS zummoosa'

Hil:

l. The comounications by petitioirer's employees to munsel att cov-

ered by tbc iltomey-cli.ni p;*itugt ineofar as the responc€q to the

qucstioorr.irls rod auy aotes re0ecting reepoDE€s to intcn'iew quE'tiont

ere coaoeracd.

(s) The coolrol group tea. ovcrloole ttre fect thst arch privil€Se

ati"t" to protec-t Dot ooty iU" giving of profcsiond advice to thoe who

cra rct oo it but atso the giving of infonnetion to tlie lawl'er to

easbte hin to give sound and informed advice' Whilo il the cese of

the individual clieot the provider'of information end tle permn who

r.ts oD tbe lawyer'e advice are one a.nd the eamg ia the eorporetc

(lotcxt h rill frequently be eoployeee beyoud the control group (ar

deined by tbe Court of Appeals) who will pocee the infonrstio[

oceded by thc corporation'a laryere. MiddlCeve!-and indeed lowtr'

la/ekplo)'e€s can, by actions within the rope of their enploloeat,

eobroil ttie corporstiotr in serioue legal diffeultieo, 8Dd it is only netural

4.9 LW 4094 The linited .Srarcr LAW WEEK l-I3Al

ants corrrluetirrg utr utttlit of otre rtf lx'titir)lt('l't forrtign sub-

sirliarics tliseot't'rctl tlrat tlrt suluidiary ttrurk' ;ru1'trtetrte to or

for the berrr'fit of forcigtr gtlvertttttt'ttt ollicials in order trr

Fecuro goverrrtttettt busittcse. 'fhtl acr'outrtarrts ro informed

Mr. Gerard Thotttas, pctitiotrer's Vica-I)rcsiclnnt, Secretery,

and Gerrcral (trunstl. Thotrrug is a trrcrrrlrr of tht Michigarr

and New York burs, arrd has lx'r,tt petitiotrcr's Ccneral Courr-

eel for 20 yearu. llt,eotrsultcd uith outsirir.counacl arrd R, T.

Parfet, Jr., petitiorrer's ('huirtrtan of the Board. It rvas de-

cided that the cotrr;ralty sould cotrduet an intprnal investiga-

tion of s'hat nere tt,rmed "qucstiotrable paynrents." As part

of this investigatiotr the atlortreys prepared a letter contsining

a qur.stiorrnaire shiclr \r'as s(,r)t to "ull foreiglr general aud area

nranagers" over the ('hairrrran'e rigralure. Thc lettrr lrcgan

by noting reeerrt disclosurts that r*veral Anrerican eonrpeniee

rnadc "possibll, ill'gal" l)a.ytnr.nts to foreign govt'rnment offi-

cials and ctnJrlrasizcd that the rrrurrgernent needed full in-

formation coneerrrirrg any suelr puyrlrents rtrade by Llpjohn.

The letter in<licated that the ('hainnan had asked Thomas,

identified ag "the eolnpany'E General Counsel," "to conduct

an inveEtigation for the pur;rose of deterrnining the nature

and magnitudc of any payments nrade b1, the Upjohn Com-

pany or 8ny of ite gubsidiaries t(, any errrployee or offieial of

a foreign govertrment." The qucstionnaire sought deteiled

information corrcerning sueh pal'rnents. Managers were in-

struckd to treat the investigation as "highly confidential"

snd not to discusg it with an-l'one other than Upjohn em-

ployees who nright be helpful rn providing the requested

inforrnation. Responses n,ere lo be serrt directly to Thomas.

Thomes and outside c<.,utrsel also intervie*,ed the recipients

of the queationnaire and sorne ilil other Upjohn offieers or

employees as part of the invesligution.

On Illareh ?6, 1070. the eolr,parry voluntarill' sul;mitted a

prelinrinary report to the Seeurities and Exehange Conrrnission

orr Fornr 8-K disclosing eertain questionable paymente.r A

eopy of the report t'as simultarreously subnritted to the In-

ternal Revenue Serviee. s'hich inrrnediately began arr irrves-

tigation to deternrine the tax cors€quences of the payments.

Special agents condueting the investigation n'ere given lists

by Upjohn of all those interviewed and all rvho had responded

to the questionnaire. On November 23, 1976, the Service

iseued a sumrnons pursuant la 26 U. S. C. S 7602 demanding

production of:

"All files relative to the investigation conducted under

the supervision of Gerard Thomas to identify paymentg

to employees of foreign governments and any politicel

contributions mede by the Upjohn Company or sny of

ita effiliates eince January l, l97l and to determine

*'hether any funds of the Iipjohn Company had been

improperly sccountd for on the corporate books during

the eame period.

"The recordg should inelude but not be limitcd to

*'ritten questionnaireo Bent to ma,nagers of the Upjohn

Company'e foreign affiliates, and memoranda or notee of

the intervien's conducted in the United States and abroad

with officers ond employees of the Upjohn Company and

ite aubeidiaries." App. l7a-I8e.

The company declined to produce the documents specifed

in the aecond paragreph on the grounds that they wene pro.

tected frorn diaclosure by the attorney-elient prir'ilege and

constituted the work product of sttorneys prepared in anti-

cipation of litigation. On August 31, 1977. the United Statee

frled g petition seeking enforcement. of the summons under

I On Julv 26, 1978. the companl' 6lcd ra elrenduent to this report dir.

cloing funher p8]zrentr.

26 U. S. C. [( 7402 (b) arrd 711{}4 (a) in the llnitcd Statee

Distriet Oourt for thc lYcstern l)istrict of Nlielrigan. That

court adopted the reeornnrendation of a nragistrate who con-

cluded that the surnrnons should lx enforced. Petitioner

appeeled to the Court of ,lppeals for the Sixth Circuit which

rejected the magistrate's finding of a q'aiver of the ottorney-

client privilege, ti00 F. 2d 1223, 1?27, n. 12, but ageed that

the privilege did not apply "to the extent the communica-

tiona were nrade by offieers and agente not responsible for

directing Upjohn's a.ctionr in respotrsc to legal adviee . . . for

the eimple reason thst the eomrnurricatione were not the

'client,'a,' " Id., st 1y25. The court reasotred that accepting

petitioner's claim for a br<-rader applieation of tlre privilege

would encourage upper-echelotr nratragctncnt to ignore unpleae-

Bnt facts and create too broad a "zone of eilence." Noting

that ptitioner's counsel had intcrviewed officiale Euch as

the Chairman and President, the Court of Appeals remanded

to the District Court so that e detrrmi,rstion of who wae

within the "control group" could be rnade. In a concluding

footnote the court stated that the *'ork-product doctrine "is

not applicable to adrrrinistrative Eurnmonses issued under 20

U. S. C. $ 7602." Id., at 1228, n.13.

II

Federal Rule of Evidence 501 provides that "the privilelie

of a witness . . . ehaU be governed by the principles of the

common law as they may be interpreted by the courts of the

United Statcs in light of reason &nd experience." The attor-

ney-client privilege is the oldest of the privileges for con-

fidential communications knowtr to the common lew. 8

Wigmore, Evidence $2290 (McNaughton rev. 196l). Its

purpose is to encourage full and frank comnrunicetion between

attorneys end their cliente and thereby promote broader public

interegts in the observance of law end administration of jua-

tice. The privilege recognizes that sound legal advice or

advocacy serves public ends and thac such advice or advo-

caey depends upon the lanyer being fully informed by the

client. As we stated last Term in Trommel v. United States,

445 U. S. 40. 5l (1980), "The attorney-client privilege reete

on the need for the advocate and eounselor to know all that

relatee to the elient'e reasons for seeking representation if

the professional mission is to be carried out." And in I'u[er

v. United States,425 U. S. 391, 403 (1976), s'e recognized the

purpose of the privilege to be "to encourage clients to make

full disclosures to their altorneys." Thig rationale for the

privilege has long been rerxrgnized by the Court, see Hrnt v.

Blackburn, 128 t-. S. ,l(i{. 470 (1888) (privilege "is fourrded

upon the neeessity, in tlre irrterest and adrrrinistration of

juatice. of the aid of persons huvirrg knosledge of rhe law and

akilled in its practice, s'hich assistatrce ean only be eafely

and readily availed of n'hen free frorn the eonsequen(Es or

the apprehension of disclosure"). .-l,drnittedly complieationa

in the application of the privilege arise q'hen the client ie a

corporation, which in theory is un artificial creature of the

law, and not en individual; but this Court has assunred that

the privilege applies rvhcn tlre elient is s eorporation, United

Srores v. Louisuille & \'ashuitle R. Co.,234 U. S.318,336

(1915), and the Government does not contest the general

proposition.

The Court of Appeals, houever, eonsidered the application

of the privilege in the mrporate rontext to present a "dif-

ferent problem." sinee the client \ra6 on inanimate entity and

"only the senior management, guiding 8t)d integratiug the

eeveral operatione, . , e8n be said to possess an identity

analogoue to the eorlxrration as a $'hole." 600 F. 2d, at 1226.

The first c&se to articulate the so-ealled "control group test"

I.I3.BI The llnitecl Stotee LAW S'EEK 4.9 LV 4.095

ado;rtod by tlte r"ortrl lnlou', City of Philadtlphh r'.ll'enting-

htruec I)ltctric (''or1t.,210 P. Suplr. 4HiJ. ;18.'r (Hl) I'}a. ), ;retition

for nratrdatnus alrrl lrrolribition denicd, 312 }.. 211 742 (CA}

l$02), tr.rt. derrir'ri.3;3 1'. S.gl:J (1963). reflected a girrrilar

crrrrccptual apprr.,ueh :

"Keeping itr rnind that the quostion is, Ie it lhe e()rl)or8-

tion n'hich is seeking thc lauyer's arlvice whcn the as-

eerted privileged cornrnunication is made?, the tnost eatie-

faetory rclution, I think, is thut if tlre elnplol'ee rnaking

thc eonrnrunieotton, of uhutt'ver rarrk he may bc, is in a

Jrcsition to control or e\'('n lo take o nubstarrtial part in

a decision uhout any a(:tion rrhich the corporation lnoy

tuke u;xur the atlviee of the nttorne)', . . , then, irr effeet.

hc b {or pertoniitca.l the corporotiort ulron hc tnakas hic

disclosure to the lawyer and the privilege would apply."

(Emphasis suPPlied.)

Such a view, we think, overlooks the feet that the privilege

exists to protcct not only the giving of professional advice to

thoae who can act <ln it but also the giving of information

io the la*yer to enable him to give xrund and informed

advice. See Trommel, 45 V. S., at ,11 ; Fiahet,425 U. S., at

a0il. The 6nt step in the reeolution of any legal problem is

ascertaining the factual background and sifting through the

facta with an eye to the legally relevant. See ABA Code of

Profeesionsl Responsibility, Ethicel Consideration,l-l:

"A lawyer should be fully informed of all the facts of

the matter he is handling in order for his client to obtein

the full advantage of our legal Eystem. It ie for the lawyer

in the exercise of his independent professional judgment

to separatc the relevant and important from the irrele-

vsnt snd unimportant. The observance of the ethical

obligation of a lasyer to hold inviolate the confidences

and Ecrets of his client not only facilitates the full de-

velopment of facts essential to proper repreeent&tion of

the elient but also encourages laymen to seek early legal

assiatance."

See deo Hickman v. Taylor,329 U. S. 495, 5ll (1947).

In the case of the individual client the provider of informa-

tion and the person who acts on the lawyer's advice are one

snd the 8Eme. In the corporat€ context, however, it will

frequently be employees beyond the eontrol group as defined

by the court, belor'-"offieers and agents . reeponsible for

directing [the compeny'e] aetions in response to legal ad-

yi6p"-*'ho will poesess the information needed by the eorpo-

ration't la*yers. MiddleJevel-and indeed lower-level---em-

ployees can, by actions u'ithin the scope of their employment,

embroil the corporetion in snrious legal difficulties, and it ig

only nrtural that these employeer would hsve the relevsnt

information needed by corporate counsel if he is adequately

to adviee the client *ith respect to euch sctual or potentiel

difficulties. Thia fact was notd in Diuenified Indutriec, Inc.

v. Mercdith, 572 F. 2d 596 (CA8 1978) (en banc):

"In 8 @rporation, it may be necess&ry to glean informa-

tion relevent to a legal problem from middle msnsge-

ment or nou-malragetnent pertonnel as well as from top

executives. The attorney dealing with a complex legal

problem 'ie t}rus faced with a "Hobeon'e choice." If he

interviews employees not having "the very highest au-

tlrority" their eommunications to him will not be privi-

leged. If, on the other hand, he interviews only those

employeee nith t}e "very highest authority," he may

find it extremely difficult, if not impossible, to determine

what happened."' Id., at 608-609 (quoting \l'einschel,

Crcrporatc Employee Interviews and the Attorney-Client

Privilegc, I2 ts. C. Ind. & Comm. L. Rev. 873, 870 ( 1070) )

The control group teat edopted by the court below thue

fruetratce the very purpose of the privilege by discouraging

the comrnunication of relevanl, information by employees of

the client to ettorneys sceking to render legel advice to the

client corporation. The attorney's advice s'ill also frequently

be more eignificant, to noncontrol group members than to thoee

who officially sanction the advice, and the control group test

makeg it more diffieult to convey full and frar* legal advice to

the employeca who will put into effect the client corporation's

policy. See, e. 9., Duplan Corp. v. Deeing Milliken, hu.,

397 F. Supp. 1146, l164 (SC 1974) ("After the lawyer forms

hie or her opinion, it ie of no irnrnediate benefit to the Chair-

man of the B<lard or the Presidetrt. It must be given to the

corporete personnel who will apply it.").

The narrow scope given the attorney-client privilege by the

court below not only makrrs it difticult for eorporate attorneys

to formulatc sound advice when their client is faccd with a

spccific legal problem but aleo threateng to limit the valusble

efforts of corporate counscl to ellsure their elient's complianee

with the law. In light of the vast and complieated'array of

regulatory legislation confrontirrg the modern corporation,

corporations. unlike nrost individuals, "eonstantly go to law-

yers to find out hos' to obey the law," Burnharn, The Attor-

ney-Client Privilege in the Corporate Arena, 24 Bus. Law.

901, 913 (1969), particularly sinee compliance rvith the laq'

in thia area is hardly an instinetive matter, w, e. g,, United

Stotes v. United States Gypsun Co.,438 t'. S. 422, UM4l

(1978) ("the behavior proscribed by the [Sherman] Act is

often difficult to distinguish from the gray zone of soeially

acceptable and econolnically justifiable business conduct").'

The test adopted by the eourt below is difficult to apply in

practice, though no abstractly formulaCed alrd unvarying

"test" will necessarily enable courts to decide questions such

aa thie with mathematical precision. But if the purpos€ of

the attorney-client privilege is to be served, the attorney and

client must be able to prbdict u'ith some degree of certainty

whether partieular diseussions u'ill be protected. An uneertain

privilege. or one which purports to be certain but resulte in

widely varying applications by the eourts, is little better than

no privilege at all. The very terms of the test adopted by the

eourt, below suggest rhe unpredictability of its application.

The test restriets the availability of the privilege to those offi-

cers \r'ho play a "substantial role" in deciding and direeting

a corporatiotr's legal response. Disparate decisions in cases

applying thie test illustrate its unpredictability. Conrpare,

e. g., Hogat t'. Zletz,43 F. R. I).308.31;'316 tND Okla.

1967), atr'd in lrart strb nolr. latto l'. Hogan,39? F' 2d 086

(CAIO 1968t (control group irrelrrdes lnansSers and. a-ssistanl

managers of patent division and researeh and developnrent

department) s'ith Congole um Industries, Inc. t. GAF Corp.,

49 F. R. D. 82, 83-c5 (EI) Pa. 1960), aff'd. 478 F. 2d 1398

(CA3 t973) (.cotttrol group includes only division and corpo-

rate vice-presidents, artd trot t$'o direetors of researeh and

vice-president for production and researeh)

t The Government &rguee that the risk of eivil or criminal liabilit;" zuf-

6ees lo enzure thar corporation-' will se€'k legal advice in the aL'ence of

the protection of the privilege. This respon-"e ignores the fect thst the

deptl and qrralitl' of anf inva'trgatrons to enFure compliance with the lew

would sufier, even were thel' urrdenaken. The reslrcnse also prol'es too

much. since it applie to all eonrmunications covered b1'the privilege: an

iudividual trfing lo compll' wrth lhe tsw or faced nrth a legal problem also

has strong ineentit'e to dr.elrnt informatlott to hs la*1er, )'et lhe ttmmon

law har recrrynized the tduc of the pnvilqe b funtrcr frcilitrtia3

coElnugicstiolt.

Th* ltnitrul .Srorer LAW S/IIEK t.l3-Bl

49 Lw 4096

T[e t,otrttrtutricutittns at issut' rrcre tttade l-rv I'Jrjolrn em'

p6-r;,'." ,;;;"rr,'o'l for I-pj'rhtr trctitrg as surh' at tlrt dirrx-

tion of eorlx)rate ru1'rtt'tors itt orrltrr to sccurt' lcgul nrlvict' froltl

*rt,*f.

-'ii- ih*

"i'gitt'att'

fourrd' ")1r' Thorrrar eotrsultcd

.:itir*tir"

'Ci,"i.ut""

irf the }krartl arrd otrtside e.unsel and

,h;;J;, trr,tluettd a faetrral irrr.t,stigati,rr r, dercrr,irre the

r"ir* ,t,a

"-telrt

of tlte rlucstionable pa1'lltetrts atd to be in o

'"rtiiit, ,r, gite lrgal uditce tn tlrc crtrrrlxtrty tcith reepect to

;;";;,;,;;rit.- (-Empharis supplied') I)et' App' I3a' Irr-

i."riti ir,,, rrot, a va ilablt f rolr r u;rptr-eehelotr rtraltagentetrt' was

;;;Ji;'suppl1, a basis f,r tr:gal u<t'iee eo,ecr,i,g c.tnpli-

""* "'i,f,

*"uiiti*. antl tax laus' foreign laws' eumency

ffilrtio,,r. rluties r, uharr:lruldr:rs, alr(l l)otc,ti8l litigation

;;:;;; ;i th"r" o,.'a''' Thc cotrttnuttit'atiotrs eotrccrrred mat-

i"r, ,rirt i,, the set-r1rc of the enrployees' corporate duties' and

;;:;;;,ri,r,','s thcrrrsfl''es $'t're sufficietrtly a$'are that they

;';r.;

'dir,;

qutstiotre<l in olt.tcr that the cor;xrration .eould

.iiifr'i.i"r-r,lti.". The questionnaire iderrtified Thomas

"r;;tf,n "Jr1,t,,y'*

(iencral ('ounsel" arld referred in its ollen-

ing tu,,*,,." to the prsible illcgality of paynrcnte such aa

a# oi". on u'hich infortnation s'as sought' App' 484' A

,L*rn"nt of poliey accotnpanyiug the queeti<lnnaire clearly

irai.""a the lesal inrplications of the investigation' The

fii.y .,r,urnent was issued ''in order that there be no uncer-

't"iriv i" the future as to the poliey with respect to the

;;;*. which are the subject of this investigation'" I-t

il-g.;-;;L-pi"hn will eomply with all lawe and regutations"'

.ri-tt"t"d ihat cnn,rni.sluus or pa1'ments "will not be used as

I'*[t"tius. for bribes or illegal payments" and that all pay-

ments muit be "proper and legal'" Any future agreements

itir, totuign distiibutors o,

"g"ntt

were to be approved "by

"

**p"ni

"ttorney"

and any questions concerning the policy

;; t L ,"r"r.id "to the eonrpany'e General Couneel'"

,fpp. fm"-fOO". This statenrent was issued to Upjohn em-

"fl"r"*

worldwide, so that even tltose interviewees not re-

ffi;; a luestionnaire n'ere aware of the legal implicatioas

oi-rt,""int.i"i.*t' Pursuant to explicit instruetions from the

Ct,"ir-"n of the Board, the comtnunications were considered

"-f,-igiiy-.onnderrtial" *jh"n mad"' App' 39a' 43a' and have

U""i l"pt eonfidential by the eompany'5 C'onsistent with

the und-erlying purpoeea of the attorney-client privilege'

ih"*

"o*nrunications

must be protected against, compelled

disclosure.

The Court of Appeals declined to extend the attorney'client

pri"il.; beyond ihe limits of the control group test for fea^r

[;;;;irg L q'ould ettt'ail severe burdens on discoverv and

a.."t" "

iroad "zone of silentr" over corporate affairg' Ap

otiotirn of the attorne.'--elient privilege to communieationa

il.T'"t',r,"* ir,rloltcd i'ete, huti'et'ur' puts the ad'ereary in

io- ,,u* lxrsition tharr if the eonrmutticatiorrs had never

ir1"n pt"*. The privilege orrll' protects disclosure of com-

irrni."ri,rr.; it does not protect tlisclosure of the ulrderlying

facte by tho-"r: sho cottrnrutriegtnd s'it'h the attorney:

"Thr, prolcr"liotr o[ lhr' privilcge cxtcttds ottly to corrr-

ntrttiraliottx ttttrl ttot lo llt'ts. '{ faet is tltre thing atxi a

eotttltrtlttieltit,ll ('(,ll({:l'lrillg tlrat faet is arr errtircly rliffer-

ent tl,irrg"l'lrr, clit'nt t'atttrot lx' trrlrrlx'lled io answer the

q,,"-it,,ri '\1'hat rlirl yott say or rvritc.to the attorney?'

but u,ay ll()t r('fus{' to tliselost' atry relevant fact within

his krtoulcrlgo trtcrcll' l'x't'nttxr ltc itr<:rtrpurutrxl a ntete-

rnent of ,r,'1, for:t irrto lrrs conrrnutticatiorr trl lris et-

i".""r'; ('ity o! ['l'ilodt:l\irio v' ll'ettingfutuae Electrit

Corp..tOS l'. Supp. t{30' ltSl (Iil ) Pu' 1962)'

See also Dittcrxifierl lntluilriett, ':r72 F' 2d" at 6ll; Stote v'

C;rr";t Ctturt, M \\'ix. 2rl ;-)':)9, '1H0' lir0 \' \\'' 2d 3lt7' 399

(1967) ("thc etttlrts ltBvt troterl tlrat s l)arty t'atrnot eon-

ceal a faet nteretl'by revcalirrg it tn his lan'yer".;' Here the

Cu.'oiun,"r,t *,r* fr,u, to t;uestiott the entpkrl'ees u'ltor t'otn-

mu,,icat,.d s'ith 'l'hotrrus rrttrl otltside counsel' L-lljolrn has

;;;;;i;;; ttre Ills .,ith a list of stteh ettrplovecs' and tlre IRS

't"* *tr""dy itrtcrvieued sorrtc 25 r'rf thern' \\'hile it would

prohuhly be nrort' colttenit'ltt for the Governtnertt to sseure

il,u ...rlt. of p.titi.rrer's itttertral in'estigation by simply

subpoenaing thi' questitrnrruires ontt notes trrken by pcti'

iinr,at;. attorrrevs. sueh consi'.let'srtiotts of cottvenience do not

ou.r.un," tho ;xrlicics senerl b1' the attorney-client privilege'

As Justice Jacjks,rl, tiott'rl itt ltis cotrt:urring opirrion in Hick'

;"; t' Ttrylor,32t, L'' S.. at Slri: "Discovery was hardly in-

tended to

-enable

t leart'e'l proft'ssiorr to perform its fune-

tions , . olt wits borrolrt'd frorrr the adversary"'

\eetlless to sa-v. ue tlccitit'orrll'the cast'before us' and do

uoi ur,,l"tatte to tlraft a sct of rules rrhich should govern

challerrges to irrvestrgutorl, subpucttas. Arry such approach

"'"riJiia"t

the spiiit of F' R' E' 501' See S' Rep' No' 93-

i#, s3d C.ng., zi Stss., 13 ("t,e rec,gnitio, of a privilege

;;; ;" conldential relationship slou]d be determined

;;-.;;sr-case b86i6") ; Trarnircl' 45 Y:.s" at 47; United

silr;;. Cnorr' u'o u. S. 360, 367 (1e80)' While such a

;""."-Uy-.r*" basis nrsy to sorne slight extent undermine de-

.irllf. "."i,"inty in the bourrdaries of the attorney-client'

"riuif"o".

it obeys the spirit of the Rules' At the same time

;;';;;11;;;;rt, tt" u,"oo "coutrol group test" sanctioned

;t ,n" Court of .{ppeals in this case cannot' consistent with

;ir,.'ptlr"irr-, ol tt

"

eotnmon la*' as interpreted ' ' ' in

figir'"i t""*n attd experienee," F' R' E' 501' govern the

development of the Iaw in this area'

III

Our decision that ti'e eommunieations by l:pjohn employees

tocounselareeoveredbytlreattorney.elierrtprivilegedis.

.ro*. of the case eo far u' the responses to the questionnaires

;il"";-"-.;;"i;. refleeting resl)ot]ses to- interview questions

Iru .orr..rr"a. The .u"Lnont reaches further' however' and

il";;;;; testifled that his noles and memorand& of inter-

;;t;" beyond reeording restlorrses to his questions' App'

;;;:}i;, gta-sea. To tlie exient that the material subject

tothesummonsisnotproteetetlbytheattorney.clientpriv-

ilege as tlisclosing eomniunieatious bct$'eetr an employee and

eounsel. q'e must reaeh the ruling by the Court of Appealg

il;; work-produer dtrtr.iDe dtres not apply to summon8e8

iesued under 26 U. -q. C. S irCIl..

The Government couL'e(-les, wisell', that the Court of Ap'

p";h;t*d end that the sork'prr'rduet doctrine does apply to

iRs-.un,rnu,,."r. (')ov Br" at ld' 4S' This doctrine $'as &n-

-i*To-roo',rg ,liscui"ion s'ill also r't relevnnt to eounsels' not€6 8nd

memoranda of inlen'tcns t:th the *rttt fonner emplovees should it-be

deterurintd thct the "ttt"ttt'ttt"ot

prrtricgt docl uol epply ro tlrein' 9r

n. 3, nrPru.

! Seten of the tG eur1,lo1-ees inten'icned ir1' counsel had tcrrnineted their

".ilo1'..r,

wirh I'pjohn rt the lime of the intenieq" App' 33a-38e'

i",Iiu"t aqnrei thet rhe privilege should nonaheleei apply lo comlnu-

or"ur;rr,. hl rhese fonrrer cruplo-.veet cottcerrrittg activities during their

rmrJ ,,f en,pk,.rnerr. \erther rhe I)istnet Coun nor the Coun of

ipp"rr' t,"i [".".ion to udrlrt*s lhts tssrte, and we deeline to decide it

r,irhour rh" btnefit of lresttneut btlo$'

' S.' .tl,p. 26s-5.t, lGir. t'lila-ll{a Re atso In n Grund Jury ln*t'

t;goiiiio,, irrs r. la t:Ll.l. l:l'19 (c.{J l9;9) ; Ia rc Grond tury stbpoena'

seg f 2d fllr. 5ll rC.t! lllll)t.

rsrcmo8istrate'srrpinion,Pet'App'lSe:..ThcresponFettotheques.

ti";;; ird rhe nottr of rhe inten'iews luve been lreat€d es eonfidential

,.i"ti"f and hrre not bet'u &*'lo'rrl to an)'one except }tr' Thomrs rld

outside eounscl."

l.l3al Tfu lJnited Storree LAW WEEK 49 LY 4097

nounced by tlre (lourt ovt'r 30 ycam ago- ilr If icl'zr an v ' Toylor

'

3m n. S.-{95 (t047). In that eat.e the Court rejected "an

iirc-pt, without pur;xrrttd nccessity or jurtiication' to eecurc-""ii*l

tr"*menis, irrivate mt'tnoratlda, and pcrsotral re'col'

;li;;. propar"d or formed by an adverse party's counsel in

;;;;; of hi, t"g"l dutieg'" /d., at 510' The Oourt not'ed

O"i;it ie eEscntiai that a lawyer work with a certain degree

oi prir*y" and reasoned thai if discovery of the material

rcught were permitted

"much of whet ie now put down in writing would rtmain

unwritten. An artorlrey's thoughte, heretofore inviolate'

would not, be hie own. lnefficiency, unfairness and aharp

practicee would inevitably develop in the giving gf ll4

'advice

and in the preparation of caees for triel' The

uff""t on the legal profession would be demoralizing'

And the interecte of ihe clientn and the cause of juatice

would be poorly served'" /d', at 5ll'

The "atrong public poliey" underlying th-e work-product doc'

;; ;- ,Iamr-"d recentlv in Lttited States v' Noblee' 422

U. S. 25, 23il24tt (1975), and has been substantially in-

;;;d in tr'u,l.rri Ruie of Civil Procedure 26 (b)(3)''

-

.i, *" state.d last Terrn, the obligation impoeed by e tax

.r--on, remaing "subleci to the trarlitional privilegee and

iimitstiona." (Jnited irotrt t. Euge, 44/1 U' S' 707' 714

(1980). Nothing in the language of the IRS summone pro-

vieions or their legislative history suggests an intent on the

part of Congress rc prectude application of the uork-product

io"uinu. ilrt" ZO (b)(3) codifies the work-produet doctrine'

;;Jth; Federal Rules of Civil Procedure are made applicable

Io--.u-.on, enforcentent proceedings by Rule 8l (e)(3)'

il. Oorota*n v. Uttited Siatee.400 1:' S' 517' 528 (1971)'

ilit"

"on""aing

the applicability of the work-product doc-

trine, the Goveinment asserts that it has made s sumcient

riroifirg of necessity to overcome its protectiona' The magie-

iot" iip"t.ntly so found. Pet' App' 30a' The Government

relies on the following language in Hbkman:

"'W'e do not mean to aey that sll nritten materiale ob-

tained or prepared by an adversary's counsel witrh an

eV" to*"td litigation are r'ecessarily free from discovery

in-"tt ""ru..

E'1.." relevant and nonprivileged facta

remain hidden in an attorney'a file and rrhere production

ofthoeefacteise8sentisltothepreparationofone'8c8t€'

diecovery may properly be hsd' ' ' ' And product'ion

",islrt

b" justffiei uiure rhe witnessee are no longer avail'

abie or may be reaehed only with difficulty'" 329 U' S''

at 5ll.

The Gol,ernment Etre&ses thar ttrtervien'ees 8re scattered acrosS

*r" gfoU"

"ra

that L'pjohn has forbidden itscmployees to on-

.ier-qu"ations it considers trrelevant' The above-quoted

i;;;; f." m Hickitan. honever, did not applv -to. "oral

tt"i"t"Int" made by sitnesses ' ' ' whether presently in the

form of lthe attorney's] mental impressions or memorandS'"

Id., tt 512. .{s to su.h nl8teri8l the Caurt did "not believe

that any sho*'ing of rrectssity can be made under the circum-

etanoee of thie cene 80 8s lo,lustify production. . lf there

ehould be s rare eituatton ,iustifying production of t'hese mat-

tere, petitiorrer'a c88e ie rrot of tlrat tyJre." kl., st 512-513'

See iro A'obler, wpro, at 2:12-2i,3 (Il'arrn, J', concurting)'

F;;r*g an attorney to disclose notee and memoranda of

witneie' oral etatemente is particularly disfavored becauee

it, Lnde to reveal the attortrey't melltel processee' 329 U' S''

at, 513 ("what he es$' 6t io n'rite down regarding wit'nesses'

i.."tf"') ;'id., tt 516-517 ("the stetement would be his [t'he

attorney'eJ language, permeated *'it'h hie inferences") (Japk-

Eon, J., concurrtng).'*R;1"

26 accordl'epecial protection to work product revealing

the-attorney'e mental processeB. The Rule permits disclosure

oi ao.urn.n* and taniible things constituting attorney work

pioau.i upon s showing of substantial need and inability to

[Uiri, tft. equivalent uithout urrclue hardship' This was the

;;Jil rppfi.a by the magistrate, Pe-t'-App'.26a-27a' Rule

ZO g*. on,'ho*"r"t, to stste that "[i]n ordering discovery

oi.r.f, materials when the required showing has been made'

the court shall protcct against disclosure of the lnental im-

f.".siorr, conclueions, opinions or legal theories.of aIt attorney

;;;th* repreaentative of a party concerning t}e litigation'"

ettt orgt dhi, t"rgr"g" does not epecifically refer to mem-

"i*a"i"*a

on Jral gtatemente of witnesses' the Hickman

*rJ tt."t ua the danger that compelled disclosure of euch

tn"'*ona"wouldrevealtheattorney'smentalprocesses.

ii-i, .t.* that thie ie the eorr' of material the draftsrnen of

il. Rril hed in mind ae deeerving special protection' See

i"t .

"f

Advisory Comrnittee on 1970 Amendment to Rules'

i.pti"t"a in 48 F. R. D. {87, 502 ("The subdivision ' ' '

g*, on to protect against disctosure the mental impressions'

ilnclusions, opiniona, or legal theoriee.' 'j-9f an attorney

;;';th"t representative of a party' The Hickmoa opinion

;;.;-tp."ti attention to the need for protecting an attorney

"g"i"J

Ji*rvery of rnemoranda prepared-from recollection

;i "*l irt"rri.*. The courta have eteadfastly safeguarded

;;"il;it"l".r* of lanyere' mental impressions and legal

theorieg . .").- il"*a on the foregoing' some courts have concluded t'hat

- J""frg of necelit/ can overcome prot'ection of work

pr"ar.i *fi.h is based- on oral statements from witness€s'

6H irtti (peimnel reillections, ,otes and memoranda

oertaining to cotrversation with witnesses) ; In te Granil Jury

';:;;;;;;;;;,;i, F. .Supp. e43, e4e (ED. Pa' 1e76) (notes or

eonrrerJation nith nitness "are so much g product of the

i;;;;;;;i.king and so little probative of the *'itnees's

IiiJ *o.at tha-t they are absolutely protected from disclo-

aure"). Thoae c$urts declining to adopt ar absolute rule

have nonetheless recognized that such materi8l is entitled t'o

.J""iJ p.ot".tior. Si. ''

g', In te Grand Juy Inuestigatbn'

;fi-r. il., ,i iiir ("speci8l considerations ' ' muet shap€

""i

trfit g ", the diecoverability of interviewmemoranda '

I"Jf,- a""i*"nts will be diecoverable only in a 'rare situa-

i["; 'f , .f. ln re Granil Jury Subpoena,.59g F' 2d' at' 5lt-512'"''i"

ao t"t deeide the iss'ue at'thig time' It is clear that

th;;;;;

"ppri"a

lr'" *-ng standard when he concluded

ililt A;"ernment had madei sufficient showing of neces'

-;il. described his notes of tlre inlen'iews as contellring "wbat I

eonsider to be the imponanr queitlons' the substutce.of the reslrcnse to

them. m1' belicfs ae tt th* ;;t;;; ot

't'tu"'

m1' behefs as to how they

related to rhe inquiry'

'n1'

titiugl"" as to hoc' thel' related 1o other ques-

tions. In some instane€€ ,i"i-il,,gfri--,* oggesi orher qucttion^< that I

would hrve to rrk or lhin; iblt i ne"d"d to 6nd elseshere'" Pct' App'

l8L

t ThL provider, t! Pennent P8n:

'A party ma1' obuin drsoovc4' of docusrentl- rnd rangible thingr other-

riec'dbcotcnbh under suMiriisron (bi(ll of thu nrle end prepared-in

tori.if,i* of litifrtiou or for trial bv or for anorber pany or by or lor

thrt otbcr prn)"s represmtertre (tncluding hie ottoroey' coDsultant'

nrrcll', indemnnor, inzurcr' or ageDt t onll'.upon a shou'ing th8r the Party

Jioi ai.-t.rl' iee .ub*t"nriri nted of the uuterials in the preperation

of his eeec and rhst he i. ,rn,rble *rrttout urtdue hardship ro obtain tbe sut>

]i.orLt .qu,".tunr of the ntarenrl: Ll orher uteans .fn ordering discovery

of-.fror,.;rlsrhenthtrrqurrtdshowitrghatbcen.made'theeourt

.irii'r-* ngnrntl tlt'closure of rhc tnental impressioru' conclurions'

;;d;. ;; lerJl rheorr*s of ttt rttorney or other rcpr.cutetivc cf s perty

anceminr the litigstion'"

Th* ltnited Stotee LAW WEEK l-r381

\

49 Lw 4O1)B

aity to overeolne the protections of the wtlrk-;lroduct doe-

;;". The trragistrate applied the "substatrtial necd" and

;;;;;.r; unrlue hardslrip" stendarrl articulated in the 6ret

"rri'oinrr"

20 (b)(3)' The notes and tntrtrtoranda sought

[i'ir,"'cor"tnment here, however, are $'ork product based on

]i"i- r1"t"nt"ntt. If they reveat cortrnrunieations' tfiey are'

ir-,f,i.-"r*, protccteri by the attorney-elient privilege' To

if,"'"r*n, it.'v au not reveal eonrtnutrications' they reveal

ii,n

"it"r,,.V.'

inental prooese(|s in evaluating the cornrnunica-

tions. As Rule 26 and Hitkman make clear' euch work

pioau"r ."r,rot be discloscd aimply on a ehowing of cub-

atantial need and inability to obtain the equivalerrt without

undue hardslriP.

\Yhile we are not prepared at this jurrcture to eay that such

matcrial is alwaya protected by the rvork-produet rule' we

iiirf. " far stroriger showing of necessity and unalailatrility

i'y

"if,"t

rr,*arrs thln was tnade by the Governmcnt or applied

;; in" rnagistrate in this case sould be neces'sary to corn;rcl

;;.i;rt". Since the Court of Aplrcals thought that the

oort -ptoar"t prot€ction was ncver applieable in an enforce-

-"it pt*."aing such as this, and since the lnagistrate whose

io.u.in"nartions the District Court' arlopted applied too

i".i.r, a standard of protection, rve think the best procedure

i'ith respeet to this aepect of the case s'ould be to reverse

tfre judgrnent of the Court of Appeals for the Sixth Cireuit

"na'.utn"na

the case to it for such further proceedings in

connectionwiththework-produetclaimasareconsistentwith

this opinion.

Accordingly, the judgment of the Court of Appeals is re'

versed.

"na

tn" case rentanded for further proeeedings'

cbrBr Juarrce ,u"o"",ffi i, part and concurri,g

in the iudgment.

I join in ParLc I and III of the opilrion of t'he Court and in

the judgment. Aa to Part II' f agree fully with the C'ourt's

i+J'ti.i of the so-called "control group" test' its reasotre for

a"i"g .o, and its ultimate holding that the colnmunications

;;; are privileged' As the Court states' however' "if

tt" futpo* of tt.ittotrey-client privilege is to be served'

ti;; ;dtr.y and the client must be able to predict with

**. a"gr". of certainty whetler ;>articular discussions will

be proteitcd." Ante, al 8. For this very reason' I believe

tt "i

*" ehould articulate s stsndard that will goverrl sit'ilar

i*,

"na

afford guirtance to corporations, counsel advising

them, and federal courts.

The Court properly relies on a variety of lactore in con-

cluding that the clnrmurrications trow before us are privileged'

a;;r, at .$-10. Because of the great importance of t'he

issue, in my vien' tlrr' (burt slrould rnake clear now that' as a

gerreral rule, a eotnlnutrieatiorr is privilegrld et leaet when' as

ii"ro,

"n

et,,loyee or f<lrtttcr .t,llloyee s,caks at the directiorr

of the rnariagenrenl, with an attorttey regarding conduct or

proposed conduct within the scope of employnrent' The

"tto-.y

must be otre authorized by t'he tnattagement to itl-

luir. irto the subject and nrust be eeeking information to

Jrri.t .ounrol in performitrg aly the following functiorrs:

iai-evalrating whether tlte etnployee'c eottduet has bourrd

or. would birrd the corlroraciott; (b) uncesing the legal corr

Bequences, if any, of that cotrduct; or (c) forrlulating appro'

priate tegal resl)onses to actione that have beett t-rr rrlay bc

taken by others with rcgard to thst cotlduct. See, e. 9., Di'

ucrdfed Inilutties, Inc. v. Mcredith, 572 F. 2d 596, 600

(CA8 1978) (err hanc) ; Harper & Rou Publislrcrs, Inc. v,

Decker,423 F. 2,J 487,491-4112 (C.{7 l97l). afr'd by an

equally divided Court. 400 U. S. 348 (1971); Duplun Corp.v.

Deering ltlilliken, Inc., 397 F. Su1rp. 1140, 1163-1165 (SC

l9l.'o). Other colnttrutricatiolts betu'eetr etnployees attd cor'

porate counsel rnay irrderxl be llrivileged-as tlre petitioners

and several azrrlci have suggested in their lrrollosed forrnula-

tione'-but the need f<lr certaitrty doeg uot conlpel us now

to prescribe all the deteils of dre privilege iu this case.

Nevertheless, t<l say we shr-ruld rrot rcach all facets of the

privilege does not trtean that ne should treglect our duty to

provide guidance itt a case that squarely lrresetrts the question

in a traditional adversary cotrtext. Irrdeed, because Federal

Rule of Eviderrce 501 provides that the law of privileges

t'shall be govented by the prirrciples of the cottrtnolt law as

they may be interpretetl by the courts of the fruited States

in light of reason atttt exlreriettce." this Court has s sl)ecisl

duty to clarify aspects of the lau-of privileges lrroperly be-

fore us. Siruply asserting that this failure "trtay to sonte

slight extcnt undertttirte desirable eertaittty," atte, at 12,

neither mininrizes the cotrsequettces of cotrtitruitrg urrcertainty

bnd confusion ttor ltarntotrizes tlte irlhererrt dissotraltce of

bcknowledging that ulrcertuirrty while declinilrg 0o clarify it

tviLhin the franre of issues preserrted,

DA N r E L M. c R r B BoN,

Hff,Tlr3l;.?"f

,,slSE,?i:'il t6i1i:TR:

$+'ffile^*,ilrff it#iig*g#',gxa:;:r"Ttt'*t+n^,*

siY:;;e il:ili0bE ioHNiiiiii'J;ti;D'rartment ittorncvr' with him on

thc bhcf) for rcsPondenu.

-EfrI"f for Petitioncn' !l-23.:rntl n' !'i: Brief for 'futrerican Bar

Aoo.i"tion as &rictrr C'urr'uc Hi' ttll(l u' ?: ljritI on Behdf uf '{lrt'rican

Ailat" .f Tti*l l;.rw1r'rs rr,tl li3 hrn l'irnr-' i't^< '4'nici Cutiue $-10' strd

a. 6.