Clark v. Marengo County Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law for the United States

Public Court Documents

June 20, 1985

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Schnapper. Clark v. Marengo County Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law for the United States, 1985. 2ad54949-e392-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c999f78c-c3d6-4ffc-822b-5f14498cb8b9/clark-v-marengo-county-proposed-findings-of-fact-and-conclusions-of-law-for-the-united-states. Accessed February 10, 2026.

Copied!

l

-- ..

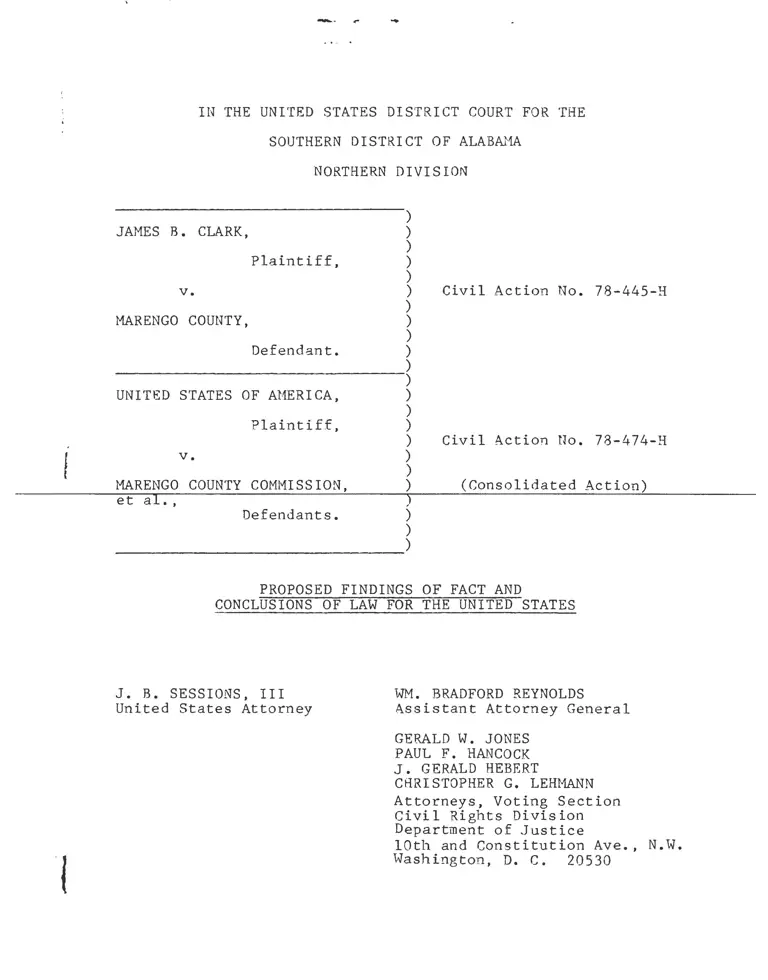

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

NORTHERN DIVISION

)

JAMES B. CLARK, )

)

Plaintiff, )

)

v. ) Civil Action No. 78-445-H

)

MARENGO COUNTY, )

)

Defendant. )

)

)

UN I TED STATES OF AHERICA, )

)

Plaintiff, )

) Civil Action No . 78-474-H

v. )

)

MARENGO COUNTY COMHISSION, ) (Consolidated Action)

et a . '

Defendants. )

)

)

PROPOSED FINDINGS OF FACT AND

CONCLUSIONS OF LAW FOR THE UNITED STATES

J. B. SESSIONS, III

United States Attorney

WM. BRADFORD REYNOLDS

Assistant Attorney General

GERALD W. JONES

PAUL F. HA.l\!COCK

J. GERALD HEBERT

CHRISTOPHER G. LEHMANN

Attorneys, Voting Section

Civil Rights Division

Department of Justice

l Oth and Constitution Ave., N.W.

Washington, D. C. 20530

<\

..

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

, SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAJ~

NORTHERN DIVISION ..

)

JAHES B. q .. ARK, ) .t

)

Plaintiff, )

)

v. ) Civil Action No. 78-445-H

)

l1ARENGO COUNTY, )

)

Defendant. )

)

)

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, )

)

Plaintiff, )

) Civil Action No. 78-474-H

v. )

)

l'1ARENGO COUNTY COHMISSION, ) (Consolida~ed Action)

et a ..

Defendants. )

)

)

PROPOSED FINDINGS OF FACT AND

CONCLUSIONS OF LAW FOR THE UNITED STATES

J. B. SESSIONS, III

United States Attorney

" . ..

WM. BRADFORD REYNOLDS

Assistant Attorney General

GERALD W. JONES

PAUL F. HANCOCK

J. GERALD HEBERT

CHRISTOPHER G. LEHMANN

Attorneys, Voting Section

Civil Rights Division

Department of Justice

lOth and Constitution Ave., N.W.

Washington, D. C. 20530

..

,,

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

I. INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY •••••.•••..••••••.••

I I. PROCEDURAL HISTORY • • • • • . • . • • • • • • • • • • . • . • . • • . 3

III. FINDINGS OF FACT............................ 7

IV.

A. BaCkground . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

B. Efforts by Black Candidates to Achieve

Elective Office ..•••......•••.••..•.•..• 8

C. Participation by Black Voters .•....••.•. 11

D. Maintenance of the At-Lar~e tlection

Systems • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 1 5

E. Existence of Racial Bloc Voting •.•.••••. 17

F. Appointment of Black Poll Officials ...•• - 22

G. The Socioeconomic Condition of Marengo

County's Black Citizens . . •• . .. . . . •••.. .• 24

H. The Effect of Socioeconomic Disparit~es

on Black Political Participation •.•.••.• 29

CONCLUSIONS OF LAW

., ....•.......•. -.......... ~ .. 32

•

JAHES B.

v.

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

NORTHERN DIVISION

)

CLARK, )

)

Plaintif-f, )

)

) Civil Action No.

tJ )

MARENGO COUNTY, ) II-

)

Defendant. )

)

)

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, )

)

Plaintiff, )

) Civil Action No.

v. )

)

78-445-H

78-474-H

MARENGO COUNTY COMt1ISSION, ) (Consolidated Action) . ,

Defendants. )

)

)

PROPOSED FINDINGS OF FACT AND

CONCLUSIONS OF LAW FOR THE UNITED STATES

I. INTRODUCTION AND SUH~~RY

In this litigation, the United States and private

plaint iffs have challenged the at-large method of electing

the Marengo County Commission and the Harengo County Board of

.,

Education as violative of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act,

as amended, 42 U.S.C. 1973, and the Fourteenth and Fifteenth

Amendments. Plaintiffs allege essentially that the at-large

· , electoral system denies black citi.zens of the County equal

•

·~

"

- 2 -

opportunity to participate in the political process and

to elect candidates of their choice to the respective County

governing bodies.

This case is currently on remand from the United States

Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit, United States v.

Marengo County Commission, 731 F.2d 1546 (1984). which directed

this Court to supplement the record with any evidence that

m~ght · tend to affect the appellate court's findings of a

violation of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act as of 1978

(when this case was originally tried).

According to the court of appeals, the "defendants

Pear the burden of establishing that circumstances have

changed sufficiently to make our findings of discriminatory

results in 1978 inapplicable in 1984." 731 F.2d 1575. On

remand, ·this Court held two evidentiary hearings and, as

explained below, defendants have failed to meet their burden.

The same circumstances that were present in Marengo County

in 1978 continue to the same or greater degree today:

(1) there remains a dearth of black officials elected to

· county-wide office; (2) th~re is a continued pattern of

strong racial bloc voting; (3) there continues to be a stark

socioeconomic disparity between the black and white populations

which has been shown to affect adversely the ability of

black citizens to participate effectively in the political

. '

'

!

- 3 -

process; and (4) there is continued failure of elected and

political party leaders to assimilate black citizens into the

political process and local government.*/ Because all of

these circumstances, taken together, operate to deprive the

~ County's black citizens of equal political opportu~ities,

there remains today the same need for the relief sought by

0

plaintiffs in 1978, namely, the formulation and implementation

of racially fair election plans for the county school board

and county commission.

II. PROCEDURAL HISTORY

The United States filed this case on August 25, 1978.

The case was consolidated with ·a private class action filed

in 1977 by 1>lack \Toters. A four day trial \las held on

October 23-25, 1978 and January 4, 1979. On April 23, 1979,

this Court issued an opinion and entered judgment for defendants.

This Courrt determined that while intentional discrimination

could be inferred from an aggregate of factors articulated in

Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir. 1973) (en bane),

aff'd on other grounds sub nom. East Carroll Parish School

Board v. Harshall, 424 U.S. 636 (1976) (per curiam), such an

*/ Of course, the same history of official discrimination in

the state and county, and the same electoral system, complete

with such discriminatory enhancing procedures as county-wide

balloting, majority vote requirements and anti-single-shot

provisions, remain in place, just as they did in 1978.

"

- 4 -

inference was not warranted here; The court concluded that

plaintiffs had not proved that the at-large system was enacted

or being maintained with a racially discriminatory purpose.

The United States appealed. While the appeal was

pending, the . Supreme Court decided City of Mobile v. Bolden,

446 U.S. 55 (1980), in which a plurality of the Court concluded

that a showing of purposeful discrimination is a necessary

ingredient of a violation of the Fifteenth Amendment, and a

major i ty of the . Court held that the factors used in the Zimmer

analysis were insufficient to show a violation of the

Constitution. Thereafter, the court of appeals in this case,

~

upon motion of the United States, vacated the judgment of

this Court and rananded for further proceedings "tncludtng

the presentation of such additional evidence as is appropriate,

in light of the decision of the Supreme Court in City of Mobile

v. Bolden." ·

While this case was pending on remand, the Fifth

Circuit decided Lodge v. · Buxton, 639 F.2d 1358 (1981), aff'd

sub nom. Rogers v. Lodge, 458 U.S. 613 (1982), holding that

the Supreme Court's decision in Nobile did not require direct

evidence of d iscrim ina tory intent, but stating, "an essential

element of a prima facie case [of ,unconstitutional vote

dilution] is proof of unresponsiveness by the public body

- 5 -

in question to the group claiming injury." 639 F.2d at 1375.

Following the decision in Lodge v. Buxton, this Court, on

July 30, 1981, again ordered judgment for defendants on the

ground that this Court had previously concluded that plaintiffs

had failed to prove defendants' unresponsiveness to the

particularized needs and interests of Marengo County's black

citizens.

The United States again appealed and the court of

appeals granted the government's motion to hold the appeal in

abeyance pendirig the Supreme C~urt's review of Lodge v.

Buxton. On July 1, 1982, the Supreme Court affirmed the

result in Lodge, but contrary to the court of appeals' decision

~

in Lodge, the Supreme Court found that unresponsiveness is

not an essential element of a claim of unconst1tut1onal vote

dilution. Rogers v. Lodge, supra, 458 U.S. at 625 ~ .• 9.

In addition, two days prior to the Supreme Court's

decision in Rogers v. Lodge, Congress amended Section 2 of

the Voting Right Act. In amending Section 2, "Congress

redefined the scope of Section 2 of the Act to forbid not .

only those voting practices directly prohibited by the Fifteenth

Amendment but also any practice imposed or applied in a

manner which results in a denial or abridgement of the right

••• to vote on account of race •••• " United States v. Marengo

County, supra, 731 F.2d at 1553.

-----------------------

·.

- 6 -

On May 14, 1984, the court of appeals decided this

case, applying amended Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act and

concluding that there was a clear violation of Section 2.

United States v. Marengo County Commission, supra, at 1574.

The court of appeals held that Marengo County's at-large

election system had the proscribed racially discriminatory

"result" as of the time of the 1978 trial. 731 F. 2d at

1574-1575. The court of appeals also concluded that in view

of the convoluted procedural history of the case as well as

the five years that had elapsed since trial, the case should

be remanded to de.termine whether the current conditions in

Marengo County had changed since 1978. The court of appeals

refore remanded the case to this Court "to allow .the

parties to update the record and to supplement the record

with evidence that might tend to affect our f inding of dis

criminatory results." 731 F.2d at 1574. That court further

noted that "the defendants bear the burden of establishing.

that circumstances have changed suff iciently to make our

findings of discriminatory results in 1978 inapplicable in

1984." 731 F.2d at 1575.

An evidentiary hearing was held before this Court on

August 6, 1984. The pur pose of the h earing wa s "to determine

whether or not to grant the United States' motion for a

preliminary injunction enjoining the defendants from holding

a t l a r g e ele ctions [in Sep tember 1984] for positions on the

}1arengo County Commission and the Harengo County Board of

- 7 -

School Commissioners." (Findings of Fact and Conclusions of

Law, August 20, 1984 at 1.) On the basis of the evidence

presented by the United States at the Au~ust 6th hearing,

and in view of the fact that "defendants offered virtually no

evidence of ahy improvanent in conditions in Harengo County

since 1978" (id. at 3), this Court granted the requested

injunction. The Court also found that "the Government has

provisionally demonstrated that little or no change has

occurred in Harengo County [since 1978]" (id. at 5), and

that "based upon the ~vidence presented by the plaintiff, it

appears that there is a substantial likelihood that the

plaintiff wi~l prevail on the merits." (Ibid.)

A further evidentiary hearing was held on March 4-5,

1985. On the basis of the evidence offered at that hearing,

and all of the evidence of record, the Court now renders these

findings of f~ct and conclusions of law.

III. FINDINGS OF FACT

A. Background

1. Harengo County is a rural county located in the

southwestern portion of the State of Alabama. The breakdown

of the county's 1980 population and voting age population

(VAP) by race is as follows:

1980

1980 VAP

Total

25,047

16,534

White (%)

11,663 (46.6%)

8,460 (51.3%)

Black (%)

13,346 '(53.3%)

8,045 (48. 7%)

..

,.

- 8 -

(Gov't Ex. 7 . at 8-9.) According to records compiled by the

county (Gov't Ex. 3), the breakdown of registered voters, by

race, for 1984 is as follows:

Reg. Voters

Total

18,437

White (%)

1o ; o51 (54.5%)

Black (%)

8,366 (45.5%)

2. Both the Marengo County Commission and the Board of ~

Education continue to consist of five members elected at-large

with a requirement that one member reside in each of four

residency districts. Hembers are elected to four-year terms

on a staggered term, majority vote basis.

B. Efforts by Black Candidates to Achieve Elective Office

3. Elective office in Marengo County has proved to be

no more accessible to blacks in the years since 1978 than in

the years preceding it. No black persons have won election

to the l1arengo County Commission and only one black, elected

without opposition, serves on the Harengo County School Board.

No black candidate with white opposition has been elected

to county-wide office or to the School Board in elections

since 1978. Qualified black candidates made unsuccessful

challenges for seats on the County Commission in 1980 and

1982, for seats on the Board of Education in 1982, and for

County Sheriff in 1982. (Ex. 7, Table 1 at 4; Ex. 10.) As

noted e~rlier, the 1984 elections for the County Commission

and the County Board of Ed ocation were enjoined by this Court.

- 9 - ....

'::·

4. Although black candidates have continued to seek

election - to the Marengo County Commission and the Marengo ·

County School Board since 1978, their repeated failures at

obtaining elective office under the at-large system have

spawned both discouragement and frustration. Lonnie Reaser,

for example, is a black man who ran unsuccessfully for the

..

County Commission in 1972. (Reaser Testimony at 116; Gov't

Ex. 7 at Table 1, p. 2.) After the court of appeals' May 1984

~ ....

decision in this case, Mr. Reaser decided to run for the

.. County Commission because he was "under the impression that

the county h~~ been districted •••• '' (Reaser Testimony at 116.)

Reaser then learned that the county was planning to conduct

the 1984 election under the at-large system; consequently,

he planned to drop out of the election. (Id at 116-117.) In

Reaser's view, "the major reason we are not running county-wide

is because we feel we would not have a chance." (Reaser

Testimony at 129.) Candidate :Reaser further noted that his

chances of obtaining elective office would he better under a

district election system! (Id. at 119.)

5. Reaser's campaign manager in 1984, Rev. James

Clarke, expressed similar views (Clarke Testimony at 72 and

75), and he added:

••• I told Mr. Reaser if I had to canvass

the whole county [,] I ••• [had] no faith

in an at-large election because it always

had been the same thing, we blacks run, we

fail and that discouraged me.

(Clarke Testimony at 72.)

- 10 -

6. Marengo County covers 978 square miles. (731 F.2d

at 1550.) The driving time from the southeast part of the

county (near Dixon's Mills and Sweetwater) to the northeast

part of the county (near Thomaston) is about 30 to 45 minutes.

(Id. at 121.) · The geographic size of the county continues to

be an encumbrance to black candidates as they campaign for

county-wide office. (Reaser Testimony at 120-121 .) Black

candidates, with limited financial resources, find it difficult

to campaign throughout the entire county. (Reaser Testimony

at 120.)

7. Dr. Paul T. Murray, an expert witness called by

the United States at the remand hearing, assessed the impact

of the county's size on the ability of black candidates to

get elected to county-wide office. Dr. Hurray explained:

The at-large system of electing members

of the County Commission and Board of Education

f dr ther reduces the chances of a candidate

being elected who is the choice of the black

community. A major obstacle is the size of

the county. · With a total area of 978 square

miles, Marengo County is the tenth largest

county in Alabama. The at-large requirement

forces a candidate to campaign across the

entire county. This works to the disadvantage

of the black community who generally have less

available ~e financial resources and/or more

difficulty getting the time off from work.

Both of these factors impact on the ability

to mount a county-wide race.

(Gov't Ex. 7 at 24.)

8. On the basis of this uncontradicted testimony, as

wel l as other evidence of re~ord, the court finds that the

t

- 11 -

at-large election system used to ~lect members of the Marengo

Courtty Commission and the Marengo County School Board discoufages

black voters and black candidates from participating in

the political process.

C. Participation by Black Voters

9. With regard to the voter registration opportunities

available to black ci-tizens in Marengo County, the court of

appeals made these findings (731 F.2d at 1570) (footnotes and

citations omitted):

The plaintiffs also showed that the County

Board of Registrars was open only two days a

month except in election years; that, contrary

to state law, the Board of Registrars met only

in Linden, the county seat, and failed to visit

outly1ng areas to register rural vot9rs; and

that the Board had never acted on the offer of

a black, Earnest Palmer, to serve as a deputy

registrar. The court said it did not see how

these policies discr\minated against blacks.

~

These policies, ho~ever, unquestionably

discriminated against blacks because fewer

blacks were registered. If blacks are to

take their rightful place as equal partici-

pants in the political process, affirmative

efforts were and are necessary to register

voters and to assist those who need assistance.

By holding short hours the Board made it harder

for unregistered voters, more of whom are black

than white, to register. By meeting only in

Linden the Board was less accessible to eligible

rural voters·, who were more black than white.

By having few black poll officials and spurning

the voluntary offer of a black citizen to serve

as a registrar, county officials impaired black

access to the political system and the confidence

of blacks in the system's openness.

- 12 -

10. Between 1978 and 1984, the Harengo County Board

of Registrars appears to ha~e done little to improve black

access to the political process. Prior to 1984, the Board of

Registrars never appointed a black _deputy registrar. t Aydelott

Testimony at 106 and 122.) In 1983, when the black community

requested that deputy registrars be appointed, the Board of

Registrars took no action on the request.

!;-

(Hayes Testimony

at 169.) Only one deputy registrar was appointed prior to

1984 and that deputy registrar was the Demopolis City Clerk,

Dolly Ward, who is white. (Ibid.)

11. In 1984, the sole black member of the three-member

Marengo County Board of _ Reg is trar s ( Hr s. Hayes) went to rural

Sweetwater in }~rengo County for two or three ~ays to conduct

voter registration. (Aydelott testimony at 104-105.)

Approximately fifty persons each day were registered by

Mrs. Hayes, which Hrs. Aydelott acknowledged was a "very

good" turnout. (I d. at 123.) This "very good" turnout is

tangible evidence that there was an unfulfilled need prior

to 1984 to appoint black deputy registrars to go out into

rural Marengo County and register people to vote. (Id. at

123-124.)

12. Prior to 1984, Mrs. Hayes conducted registration

at her home in the southern part of the county on an informal

basis prior to the appointment of any deputies in that area.

(Hayes Testimony at 170-172.) All of the persons registered

by Mrs. Hayes at her home v.ere black. (Ibid.) She did this

- 13 -

as a "convenience" to people because the 17-mile trip to

Linden was burdensome. Mrs. Hayes was told to discontinue

this practice by Hrs. Aydelott, the Board of Registrars

chairperson. (Id. at 172.)

13. In May 1984, the Alabama Legislature enacted Act

Ne. 84-389. This legislation required the appointment of

deputy registrars in ever.y county in the State of Alabama,

including M~rengo County. This legislation also provided

that "at least one or more deputy registrars [shall be appointed]

in each precinct in [each] county for a four-year term •••• "

(Declaration of Jerome Gray at 2.) The Board of Registrars

has not fully complied with this law, as deputy registrars

have not been appointed for each precinct. (Aydelott Testimony

at 107.) Only one black deputy registar has been appointed

F ~

in Demopolis (ibid.), which is the county's largest city and

which is about 50% black. (Gov't Ex. H.)

14. Pursuant to Act No. 84-389, deputy registrars

were appointed in Marengo County in June/July of 1984. In

1984, seven whites and twelve blacks were appointed deputy

registrars by the Board of Registrars. (Aydelott Testimony

at 107-108.) During the latte~ part of 1984, and with the

aid of these deputy registrars, the following number of

persons registered to vote in Marengo County:

..

,,

"

- 14 -

1984 No. of Persons Registered

Month Black White Total ..,

June 58 83 141

July 93 54 147

August 99 48 147

September 69 47 1 1 6

:.

October 312 219 531

(Declaration of Jerome Gray at 2.)

15. This registration of over 600 black and 400 white

voters in Marengo County within a five-month period of time

is a clear indi~ation that there was a need for deputy registrars,

par~icularly among unregistered black voters, prior to 1984. ~/

Because defendants ha11e failed to present any n~ason whatsoever

for the failure of county officials to appoint deputy registrars

prior to 1984, the court finds that the failure and refusal

to appoint deputy registr~rs was done with an awareness that

black access to the political process was being impaired as a

result •

• 16. Although black voters today are able to register

and to vote in Marengo County, black citizens continue to

express concern and fear that their public support of black

candidates will result in some form of economic retaliation

*I Pat Dixon, Chairman of the Marengo County Voter Registration

Project, testified that surveys done in parts of the county

by her group indicated that there were 6,000 unregistered

persons in the county. (Dixon Testimony at 145.)

- 15 -

against th,em. (Clarke Testimony at 82-91 and Rodgers

Testimony at 210-211.) As Reverend Clarke explained, blacks

who are employed by whites--particularly black teachers in

the Marengo County school system--"truly cannot get involved

in the campaign because of their fear of [losing] their

jobs." (Id. at 86.)

;---

Because blacks in Marengo County are

economically dependent on whites, black candidates encounter

reluctance in soliciting black persons to work publicly on

the campaign. (Id. at 81 and 86.)

17. Political experience in Harengo County shows that

white voters do not vote in significant numbers for black

candidates who face white opposition. (Hurray Testimony and

Lichtman Testimony; Dixon Testimony at 174; Rodgers Testimony

at 229; Foreman Testimony at 343, 351; see also 731 F.2d at

1567.) Black candidates for county-wide office thus face an

insuperable barrier in winning elections since blacks are in

a voting minority. (Hurray Testimony and Lichtman Testimony.)

That barrier is particularly insurmountable in Marengo County,

where the County Probate Judge has suggested to black

candidates that certain white residential areas are off

1 im its to campaigning by blacks. (Clarke Th s t i<'llOny at 7 4.)

D. Maintenance of the At-Large Election Systems

18. After the court of appeals' May 1984 decision

in this case, Marengo Cotmty Probate Judge Sammie Daniels

told Rev. Clarke and Mr. Lonnie Reaser "that he had talked

..... ..

- 16 -

with some white[s] to put a black person in [county government]

in order to get the Federal Government off their backs."

(Clarke Testimony at 67-68 and Reaser Testimony at 119.) The

Court construes this testimony to mean that some white political

leaders in Marengo County belieyed that the election of a

black candidate in 1984 might lead to a discontinuation of

this legal challenge to the at-large election system by the

United States.

19. Although Probate Judge Daniels denied making the

statement, his testimony is discounted for several reasons.

First, there were two credible witnesses (Rev. Clarke and

Mr. "R.eas9r) who gave unequivocal testimory that Judge Daniels

made the statement. Secondly, as a defendant in this action, ~

~

Judge Daniels is an "interested witness" and thus his self-

serving denial of the statement before this Court must be

considere~ in that context. Finally, the Court notes that in

view of the long history of racial discrimination against

black voters practiced by Marengo County officials, it is

more likely than not that the white leadership in Marengo

County would engage in such racial maneuvering to retain an

election system that disadvantages black voters.

./

: !

- 17 -

20. The Court finds that a plan to orchestrate the

el ection of a black candidate by white leaders was apparently

conceived and discussed in 1984. Because the 1984 elections

.#

were enjoined, the plan to elect a black candidate was not

carried out. The Court also finds that discussion of such a

plan suggests the presence of an informal slating process

among white leaders, and, in any event, is evidence of

defendants' racially discriminatory purpose to maintain the

at-large election systems at issue in this case.

E. Existence of Racial Bloc Voting

21. The United States offered the testimony of two

expe the .issue of racially polar r zed voting:

Dr. Paul T. Hurray and Dr. Allan J. Lichtman. Althoug

different a Ralytical methods •. */ both Dr. Murray and Dr. Lichtman

analyzed pertinent election data and found consistent patterns

of "extreme" racial bloc voting. (Hurray Testimony at 477

and Lichtman Tes~imony at 588, 591, and Gov't Ex. 7 at 9.)

*I Dr. Murray measured bloc voting using techniques of correlation

coefficients and overlapping percentages. Dr. Lichtman used

ecological regression analysis to measure voting behavior.

- lR -

22. In county elections held since 1978, both of these

experts found that black candidates for elective office who

face white opposition garner meager support among white

voters, while in every case these black candidates gained

sup~ort from a clear majority of black votes. (Murray

Testimony at 472-473 and Lichtman Testimony at 589-591.)

In everv election studied, black voters strongly preferred

black candidates over one or more of opposing white candidates,

and white voters in overwhelming numbers preferred white

candidates over black candidates. (Ibid.) As Dr. Murray

conclude~:

[T]here can be no doubt that voting in

Marengo County elections is characterized

by extreme racial polar1zat1on. Moreover, ·

the pattern of extreme racial bloc voting

is especially - evident from the 1980 and

1982 election analysis. Black can~idates

consistently run well in largely black

areas but they receive virtually no support

in white areas of the county. The percentage

of whites voting for black candidates has,

with one exception, been too small to elect

biack candidates to the county offices which

they sought.

(Gov't Ex. 7 at q.)

23. A study of the 1980 and 1982 election results

demonstrates that the conclusions of Drs. Murray and Lichtman

are amply supported hy the . evidence in the record. */ In the

1980 primary election, for example, a black candidate and a

white candidate ran for County Commission (southeast residency

*/ The election returns for 1980 and 1982 elections are

contained in Gov't Ex. 10.

•

- 19 -

district). According to Dr. Lichtman's calculations, the

black candidate received 30% of the black vote and a mere 3%

of the white vote. (Lichtman Testimony at 589 and Gov't Ex. 9.)

The black candidate lost the election, even though 22% of the

black registered voters turned out to vote as compared to

only 14% of registered whites. As Dr. Lichtman explained,

even where black voters are abie to outturn white voters,

they are unable to prevail in elections because of the near

perfect racial solidarity among white voters. (Lichtman Testimony

at 598.) In the 1980 runoff election, voting was even more

racially polarized, with the black candidate receiving 79%

of the black vote and only 1% of the white vote. (Gov't Ex. 8;

Lichtman Testimony at 589.) Dr. Murray's analysis of the 1980

elections precisely corroborates Dr. Lichtman's findings.

(Murray Testimony at 473 and Gov't Ex. 7 at

24. In the 1982 primary election, black candidates

faced white opposition in two races for the County School

Board and in one race for the County Commission. In each

. '

election, hlack candidates received solid (over 80%) support

from black voters. In each case, white voters gave less than

10% of their votes to black candidates. (Gov't Ex. 8.) In

the 1982 runoff election for County Commission (there were no

runoff elections in the School Board races), 91% of the black

voters cast their ballots for the black candidate and 3% of

the white voters voted .for the black candidate. (Gov't Ex. 8.)

lS. Defendants did not offer any evidence in rebuttal

to the strong statistical analyses of Drs. Murray and Lichtman.

Instead, defendants presented testimony of two black persons

- 20 - .1

':'·

~ who have been elected to local office in ~1arengo County:

..

Mr. Moses Lofton and Hr. Charles Foreman. */ Mr. Lofton,

who is 80 years old, was first appointed to the County School

Board and he was then elected without opposition. (Lofton

Testimony at 354.) Mr. Foreman, who is 68, was first appointed

to the Demopolis City Council and he subsequently ran against a

black opponent. (Foreman Testimo~y at 333.) Neither black .

officeholder has ever faced white opposition in an election.

Mr. Foreman gave generaliz~d testimony to thE!: effect that white

voters vote for black candidates in Marengo County. (li. at

333.) **/ Dr. Lichtman underscored the limited value of such

anecdotal, subjective testimony concerning racially polarized

voting where, as here, there is objective statistical evidence

presented on that issue. (Lichtman Testimony at 602-603.) As

.,

Dr. Lichtman correctly noted, a lay witness who proffers testimony

that black candidates who faced white opposition get "some"

white votes are not able to quantify their claims. (Foreman

Testimony at 343; Lichtman Testimony at 602.) Thus, there was

no quantitative dimension to their assertions. As noted above, .,.

hoth expert witnesses called by the United States statistically

quantified the precise extent of racial bloc voting and their

*/ The county defendants also produced several black witnesses ·

who in<iicated that black people of Harengo County today do

not suffer harassment when they register or when they vote.

(See, e.g., Testimony of James Lofton at 355.) The Courtdoes

not questton either the accuracy of this testimony or the

honesty of the witnesses who rendered it. But such testimony

sheds little illumination on the issue of whether black citi~ens

have an equal opportunity to participate effectively in the the

po l itical process. Black voters have voiced a clear preference

for black candidates and yet such voters have not been successful

in overcoming the white bloc vote.

**/ However, Mr. Foreman conceded that "not many" white voters

would vote for a black candidate with white opposition. (Foreman

Testimony at 343, 350-351.) ~

- 21 -

analyses shm.vs an exceedingly small percentage of whites

voting for black candidates. */ Not one witness on behalf of

the county testified that eleq~ions under the at-large system

in Marengo County were not racially polarized.

26. Finallv, the Court notes that defendants attempted

to show the absence of racially polarized voting by offering

evidence that voters cast ballots on the basis of qualifications

and not Qn the basis of race. **/ If such assertions are

true, then it must also be true that black voters in Marengo

County have determined that black candidates are better

qualified than white candidates, and white voters have determined

that white candidates are better qualified. In any e-vent,

such considerations are irrelevant because voting patterns in

Marengo County remain extremely polarized along racial lines.

It is the extent of that polarization that is at the heart of

the racial bloc voting inquiry •

. •

*I Of course, the fact that some -..1hite voters may have cast

nallots on behalf of an uncontested black candidate (Lofton

Testimony at 361) or a black candidate who has only black

opposition (Foreman Testimony at 333) does not suggest the

absence of racial bloc voting. It simply means that white

voters, to vote at all in the election, had no choice but to

vote for a black candidate who would have been elected with or

without their vote. It is far more relevant, and indeed it

happens consistently in Harengo County, that black candidates

opposed by whites receive an exceedingly small percentage of white

voter support. (See Findings of Fact, supra, at paras. 21-24.)

**/ Dr. Lichtman discounted this testimony because the social .

science studies that have been done show that when people are

asked whether they vote for a candidate based on race or on

socially acceptable reason (qualifications, issues, etc.),

the voters are likely to provide the socially acceptable

answer. (Lichtman Testimony at 603, 628-629.) Dr. Lichtman

also pointed out that the likelihood of giving the socially

acceptable answer is even greater when the voter is unable eo

remain anonymous. (Ibid.) That is especially true here, where

witnesses were asked such questions in a public forum. (Ibid.)

- 22 -

?.7. Racially polarized voting occurs when the voting

behavior of whites and blacks is both demonstrably different

and politically consequential. (Lichtman Testimony at 583-604,

633 and Murray Testimony at 470-477, 486-487, 532-534; Gov't

Ex. 7 at 4) Using this definition, the Court finds that the

extreme racially polari7.ed voting present in Marengo County

in 1978 continues unabated today. The evidence of record

demonstrates quite convincingly that from the time black

citizens wer:e first allowed to vote in Harengo County to the

present, race has remained a central issue in Marengo County

politics.

F. Appointment of Black Poll Offieials

28. Black citizens made little progress from 1978 to

1984 in obtaining appointments as poll officials in Marengo

County. Although 48.7% of the citiz~ns of voting age in

t~rengo County are black, only 10.6% (29 of 273) of the persons

appointed to work at the polls in 1980 were black. (See

Gov't Ex. 1.) */ In the 1982 elections, blacks again were

underrepresented as poll workers, as only 12.6% (35 of 278)

of the poll officials ~ere black. (Gov't Ex. 2.)

29. On April 30, 1984, a lawsuit was filed in the

United States District Court for the Hiddle District of Alabama,

*! Appointment~ of ~poll officials are totally within the

control of Marengo County officials. (Camp Testimony at 28-2Q.)

The appointments are made by the County Appointing Board,

which is comprised of the County Sheriff, the County Circuit

Clerk and the County Probate Judge. (Ibid.)

~ ------

-Vi

- 23 -

styled Harris v. Graddick, -~iv. No. 84-T-595-N. (Gov't Ex. 4.)

Plaintiffs alleged, in essence, that the appointment of poll

officials throughout Alabama was racially discriminatory and

violative of 42 U.S.C. 1983, 42 U.S.C. 1973 (Section 2 of

the Voting Rights Act), and the Fourteenth and Fifteenth

Amendments. Named as a defendant class in the case were "the

appointing authorities of each county of the State of Alabama

~xcept Conecuh County •••• " (Ibid.)

30. In June 1984, two months after the Harris v.

Graddick case had been filed, Probate Judge Daniels asked the

county's Democratic Executive Committee to submit the names

of more black people to the Appointing Board for possible

appointment as poll workers. (Daniels Testimony at 40-41.)

Probate Judge Daniels made that recommendation because he

felt that there had been an insufficient number of black persons

serving as poll workers in the past. (lbid.) Judge Daniels

agreed that appointing black poll officials would probably

give some black voters more confidence in the election process,

adding "it probably helped a black voter's feelings more to

see more black poll workers in the [polling] place." (Ibid.)

- 24 -

31. In response to an order in Harris v. Graddick,

officials in Marengo County substantially increased the number

of black persons working at the polls in the September 1984

elections. According to Marengo County's report to the court

filed in Harris v. Graddick, 41% of the poll workers were

hlack in the 1984 elections. (Id. at Attachment 3.)

32. The fact that black persons in Marengo County

were able to obtain appointments as po~l officials in more

than token numbers only as .a result of a federal court decree

is strong eviden6e of a denial of an equality of opportunity

for black citizens to participate in all phases of the political

process.

G. The Socioeconomic Cond1t1on of Mare&go County's

Black Citizens

33. There is extensive evidence in the record that

Marengo County's black citizens are generally lower in every

socioeconomic category or condition. The facts, as detailed

below, show that in every category of measuring social status

and standard of living--income, unemployment occupational

status, education, infant mortality, the extent of poverty

and the qua]ity of housing--blacks occupy a lower status and

suffer inferior conditions in comparison to whites. (See Gov't

Ex. 7 at 18.) "The [socioeconomic] gap between blacks and

..

- 25 -

whites is great and these disparities pervade all areas of

,.,.

everyday life." (Ibid.) This uncontested socioeconomic

disparity ~~versely affects the present ability of bl§ck

citizens to participate in the political process on an equal

footing with white persons.

34. "Income is the most important measure of economic

well-being." (Gov't Ex. 7 at 11 .) In Marengo County, more

than half (54.9%) of white families had incomes of $20,000 or

more, while only 12.4% of black families had incomes at this

level. (Id. at 12.) According to the 1980 Census, the median

income for white families was $21 ,449; the median income for

black famil'ies was $7,182. (Ibtd.) Per capita tncmue among

Marengo County whites is $7,184; for blacks in Harengo County,

per capita i~~orne is $2,595. ~Ibid.)

35. Employment condition is "an important source of

social status and self-esteem, in addition to being essential

<

to maintain a decent standard of living for oneself and one's

family~ Unemployment during the primary working years is

generally associated with low social standing and a low

standard of living." (~. at 13-14.) According to the 1980

Census, the black unemployment rate is more than five times

higher than the rate among whites •

..

- 26 -

36. "The concentration of blacks in low paying, low

status occupations is another sign of the extent of racial

inequality in Marengo County." (.!,i. at 14.) Nearly half of

Marengo County blacks are found in unskilled and semi-skilled

jobs. (Id. at 15.) Another 22% of black workers are employed

"in Service occupations." (Id. at 15.) Data on employees of

the defendant Marengo County reveal additional evidence of

blacks in low-level and low-paying jobs. According to the

County's records, the County employed 87 persons in 1982, of

whom 30 (or 34.5%). were black. Twenty-five of the thirty

black employees (or 83.3%) were employed in low-skill positions.

Less than 10% of the County's workers who earned salqries

above $10,000 per year were black. <li· at 15.) •

37. Dr. Murray pointed out that "[n]umerous sociological

studies have established that education is the single most

-importan_t variable in predicting a person's subsequent occupa

tional attainment" (footnote omitted). (Gov' t Ex. 7 at 1 6.)

The figures reported in the 1980 Census show that half of

blacks age 25 and older had completed eight years. of school or

less. For whites, only 14.1% were limited to an elementary

education. Nearly two-thirds of all whites had~ completed

high school in comparison to less than one-third of the

blacks. Only 4% of blacks are college graduates as compared

to 13% of the whites. (Id. at 16-17.)

- 27 -

38. The low educational attainment levels among

Marengo County blacks today are undoubtedly a product of the

inferior and racially segreg~ted public education that existed

for black children in the county until recently. Between

..

1921 and 1963, the average annual expenditure per black pupil

was $48.49; for white pupils, the average expenditure was

$105.16 per pupil. In some years, public authorities in

Marengo County spent ten times more to educate white children

than black children. <.!i· at 16-17, and of Table 13.)

39. Because the infant mortality rate is "widely

regarded as a sensitive indicator of the health status of a

population and the quality of health care received" (id. at

17), the rate does provide a critical health statistic on

blacks and whites in ~1arengo County. The statistics show

that from 1980 to 1982, "21 infant deaths were recorded in

Marengo County. Of this number, two were white infants and

nineteen were h lack infants.·" (.!i. at 1 7.) The infant

mortality rate among blacks is five times higher per thousand

births than the mortality rate for white infants. (Ibiq.)

40. Marengo County's population is relatively rural

and poor. But the level of poverty among the county~s black

population is staggering. The 1980 Census reports that

r•,

0

- 28 -

nearly half (47.1%) of Marengo County's black families live

below .the poverty level (meaning their income is insufficient

to supply an adequate diet and other basic essentials).

(Id. ·~ at 12-13.) For white families, the comparable figure is ·

7.1%. Poverty figures for individual black citizens reveal a

similar situation: 53.8% of Marengo County blacks live below

the poverty level as compared to 10.1% of Marengo County

whites. (Ibid.) If the poverty standard is extended to

include those persons living within 125~ of the poverty

level, then nearly two-thirds of Harengo County's black

'~~

citizens live near or below the poverty line, while one in

seven whites in the county are similarly situated.

41. Marengo County's blaek population is considerably

more crowded in their housing than are whites. One-fifth of

black housing is in the most crowded category (more than one

J

;,.

person per room) while 2. 4% ·of white housing is comparably

crowded. (Id. at 18.) The crowded housing inhabited by

blacks in Marengo County is more likely to be substandard.

Nearly one-fourt~ of black occupied housing units have no

plumbing at all. One-third of black occupied housing lacks

complete plumbing as compared to 2.1% of white occupied housing.

- 29 -

H. The Effect of Socioeconomic Disparities on Black

Political Participation

42. There is uncontradicted evidence that the

socioeconomic disparity described in paragraphs 33 through

41, above, affects the present ability of black citizens to

participate in the political process. Ur. Paul Murray, who

the government called ·as an expert witness on race relations

and sociology, reviewed in detail the scholarly literature

on the relationship between social status and electoral

participation. (}~~rray Testimony at 481-486; Gov't Ex. 7

at 19-23.) The scholarly works cited by Dr. Murray conclude

that less educated, less affluent persons have lower rates of

political participation than persoris of higher social status,

higher educational attainment levels and higher income. (Ibid.)

43. To assess whether the depressed socioeconomic

condition of Marengo County blacks affected their political

participation rates, Dr. Hurray reviewed election data and

voter registration data in Marengo County. (Murray Testimony

at 468-471 and Gov't Ex. 7 at 22.) Dr. Murray's study of voter

turnout rates among blacks and whites revealed that white voter

turnout usually exceeds black voter turnout. Dr. Murray noted,

for example, that "[i]n the primary election of September 7,

1982, 48.5% of the black VAP [voting age population] voted in

"1.

- 30 -

comparison to 63% of the whi.te VAP." (Gov't Ex. 7 at 22.)

Dr. Murray examined the voter turnout data in light of the

national studies which documented that persons of inferior

socioeconomic status are less likely to participate in

politics. (~. at 19-21.) On the basis of his study,

Dr. Murray concluded:

..

••• [I]t is hardly surprising that blacks in

Marengo Countv register and vote less fre

quentiy than do whites •

* * * * *

The lower participation of blacks in

Harengo County elections can be explained

by looking to their lower educational

attainments and occupational status.

Cons1der1ng their deprived status in the

community, the long history of electoral

discrimination, and the consistent lack

of success experienced hy black candidates,

_.-. the po lit ical ~--part icipat ion of Marengo

County hlacks is ~emRrkabl[yl high.

(Gov't Ex. 7 at 21-23.)

44. Dr. Allan Lichtman also conducted a detailed voter

turnout analysis. (Lichtman Testimony at 593-598 and Gov't.

Ex. 8.) After studying the relevant data, Dr. Lichtmrn's findings

were consistent with Dr. Murray's: in general, black voters have ,,.

lower turnout rates than whites. (Ibid.) In the 19R2 primary

and runoff elections, Dr. Lichtman estimated that whites comprised

n2% of those voting, whereas blacks comprised only 38% of the

voters on election dav. (Gov't Ex. 8 at 10.) In recent 1984

presidential elections, Marengo County whites were 57% of

. ,

- 31 -

those voting whereas blacks comprised 43% of the voter turnout

(Id. at 11.) */

45. On the basis of the foregoing facts, and other

evidence of record previously reviewed by the court of appeals

(see 731 F.2d at 1567-1569), the Court finds that the black

community of Marengo County suffered from, and continues. to

suffer from, the results and effects of invidious discrimination

and treatment in the fields of education, employment, economics,

health, housing and politics. The court also finds that the

low socioeconomic conditions of Marengo County's black population

depresses minority political participation today.

*/ Dr. Lichtman also noted that black voters who cast ballots

on election day actually vote in greater numbers for local

offices (~, County Commission and County School Board) than

for higher state-wide offices (~, State Treasurer, State

Public Service Commissioner). (Lichtman Testimony at 594-597

and Gov't Exs. 8 and 9.) In the 1982 primary election, for

example, less than 25% of the black -registered voters cast

ballots for .two positions on the Alabama Supreme Court, for

Alabama Secretary of State, State Treasurer and State Auditor;

whereas 28% of the black registered voters cast ballots on

the very same day in the County Commission race. (Gov't Ex.

8 at 5). Similarly, in the 1982 runoff, 30% of the black

registered voters cast ballots for State Auditor and State

Commissioner of Agriculture, whereas 33% of the black registered

voters cast ballots in the County Commission race. (Ibid.)

Dr. Lichtman's analysis also found that voter turnout was

significantly higher among black voters when black candidates

were involved in the race, as compared to those contests

where only white candidates were vying for office. (Lichtman

Testimony at 594-595 and Gov't Ex. 8 at 10.) Dr. Lichtman

found that the pattern of such voting behavior illustrated a

greater interest among black voters in elections for county

offices where black candidates were involved, than in elections

for certain state-wide offices. (Lichtman Testimony at 594-597

and Gov't Ex. 8 at 3 and 5.)

<;

- 32 -

IV. CONCLUSIONS OF LAW

1. Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. 1973,

provi des as follows:

(a) No voting qualification or prerequisite to

voting or standard, practice, or procedure shall

be imposed or applied by any State or political

subdivision in a manner which results in a denial

or abridgement of the right of any citizen of the

United States to vote on account of race or color,

or in contravention of the guarantees set forth in

section 4(f)(2) of this title, as provided in

subsection (b).

(b) A violation of subsection (a) is established

if, based on the totality of circumstances, it is

shown that the political processes leading to

nomination or election in the State or political

subdivision are not equally open to participation

by members of a class of citizens protected by

subsection (a) in that its members have less

opportunity than other members of the electorate

to participate in the political process and to

elect representatives of their choice. The extent

to which members of a protected class have been

elected to office in the State or political sub

division is one circumstance which may be consid

ered: Provided, That nothing in this section

e-stablishes a right to have members of a protected

class elected in numbers equal to their proportion

in the population.

2. As nofed above, see page 6, supra, the Eleventh

Circuit Court of Appeals determined that "the record shows a

clear violation of the results test adopted by Congress in

'J

section 2 of the Voting Rights Act." 731 F.2d at 1574. That

determination was based on the conditions that prevailed in

Marengo County in 197R when this case was originally tried.

Under the court of appeals' decision, "the defendants bear the

.. ,

,)

- 33 -

burden of establishing that circumstances have changed suffi-

ciently to make [the] finding of discriminatory results in

1978 inapplicable in 1984." United States v. Harengo County

Commission, supra, 731 F2d at 1575. In accordance with the

instructions from the court of appeals, this Court has evaluated

the political opportunities for Marengo County's black citizens

as of today and rende·rs these conclusions of la\-1.

3. At the outset, the Court notes that there has been

a dearth of black candidates elected to the Marengo County

Commission and the Marengo County School Board. While '

Section ?. contains an explicit disclaimer that "nothing in

this section establishes a right to have members of a protected

class elected in numbers equal to their proportion in the

population'' (42 U.S.C. 1973(b)), there is a disparity between

,.

the black population percentat Harengo County (53% black) and

the black population percentage on the governing bodies

(0% black on the County Commission and 20% black on the County

School Board). In Marengo County, qualified black candidates

before and after 1978 have repeatedly sought election to the

county governing bodies and have failed to win election. This

fact is relevant to the vote dilution inquiry for, as the

language of Section 2 explicitly states, "[t]he extent to which

members of a protected class have been elected to office in the

State or political subdivision is one circumstance which may be

·f

considered[.]" 42 U.S.C. 1973(b).

..

.. "

·,

- 34 -

4. In deter~ining whether black voters in Marengo

County "have less opportunity than other members of the

electorate to parttcipate fn the political process and to

elect representatives of their thoice" (42 ·u.s.c. 1973),

the Court has considered the "totality of circumstances"

j

in Marengo County. The Court has given particular attention

to the following issues: (1) the extent to which voters

cast ballots along racial lines; (2) the difficulty of black

persons to assimilate themselves into the M~rengo County

political process, including tbe continuing failure to appoint

qualified black persons to work at the polls on election day;

and (3) the extent to which black citizens of Marengo County

. bear the effects of past discrimination in such areas as

education, employment, housing and health, and the impact of

those effects on the current political opportunities of

minority voters. In compliance with instructions from the

court of appeals ·-, this Court has not conducted "a retrial of

any issues already tried and reviewed by [the court of appeals]."._

United States v. Marengo County Commission, supra, · 731 F.2d

at 1574.

- 35 -

5. The inability of black persons to obtain appointment

"' as poll officials in anything but token numbers was manifested

. ;:w:·

just last year. Black leaders were repeatedly ignored by

county officials and Democra~ic Party leaders in their requests

for ~ appointment of black poll officials. */ Such requests were

' ignored even though Marengo County officials knew full well

that the appointment of b.lack poll officials would give black

voters more confidence in the electoral process. The potential

for meaningful black political participation is less than

twenty-years old in Marengo County. It is important that

blacks gain both the knowledge of and confidence in the

election process if, as the court of appeals envisioned,

"blacks are to take their rightful place as equal participants

in the political process[.]" 731 F.2d at 1570. The facts

d ~ . ~ bl 1 emonstrate qu1te convincingly that effective ack po itical

participation in Marengo County has been impaired substantially

by defendants and other county officials.

6. The long history of racial discrimination in

Marengo County, including official discrimination aimed

*/ Black leaders were also unable to obtain appointments as

deputy registrars until 1984, when state law mandated the

appointment of deputy registrars in each and every precinct.

See Findings of Facts, paras. 10 to 15, supra. The fact that

the deputy registrars were so successful once appointed is

evidence that the .pre-1984 resistance to appoint deputy

registrars had adverse consequences for black voters.

•·

·,

- 36 -

particularly at preventing and discouraging black persons from

registering anJ voting, is undisputed. See United States v.

Marengo County Commission, supra, 731 F.2d at 1567-1568. This

historical record of discrimination has two present-day effects

in Marengo County: first, it causes blacks to register ·and to

vote in ! ower numbers than whites (see Findings of Fact,

para. 1, supra); second, it leads to present socioeconomic

disadvantages (id. at paras. 33 to 41), which in turn reduces

black participation and influen·ce in political affairs.

·. United States v. Marengo County Commission, supra, 731 F.2d

at 1567.

7. The socioeconomic condition of the black community

finds a substantially disproportionate number of black

citizens with low-grade jobs, low social status, low-income and

low-educational attainment levels. Because such educational

and economic rteficiencies contribute to the present lack of

participation in the election process, they are highly

probative in assessing whether the at-large election systems

at issue here violate Section 2 of the Voting ~ights Act.

8. In determining whether election practices and

procedures (such as the at-large systems here) deprive black

voters of an equal opportunity to participate in the political

process and to elect candidates of their choice to office,

the Court must weigh the total evidence of record. In this

..

I ,

- 37 -

case, there is very little balance, however, in the scale of

evidence before the Court, for the great weight of the evidence

points in the direction of ~a violation. Indeed, nearly all

of the circumstances relevant to a Section 2 determination

are present here: the widespread history of official discrimi-

nation, extreme racially polarized voting, the existence of

an informal slating process that can be used to manipulate

black political access, the marked disparity in socioeconomic

status between blacks and whites, the virtual nonexistence of

black electoral successes at the polls, and an election

system characterized by an unusually large election district,

a majority vote requirement, and residency districts which

pt"ec]ud e s j ngle-shot r.or bullet voting. :1

9. In view of these observations, the Court concludes

that defendants have failed to show that . the "circumstances

have changed" since 1978. Indeed, the evidence of record

shows a sweeping and pervasive denial of access to the

political process that continues to this day. ~fuere, as

here, the at-lar~e election systems have been shown to deprive

black voters of equal political opportunity, a violation of

*! The Court makes this observation mindful of the fact that

Congress has cautioned "there is no requirement that any

particular number of factors be proved, or that a majority of

them point one way or the other." S. Rep. No. 97-417, 97th

Cong. , 2 d Sess. 2 9 (1982) (footnote omit ted) •

·,

- 38 -

Section 2 is shown. The at-large method of electing the

Marengo County Commission and the Marengo County School Board

continues to violate Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act,

42 U.S.C. 1973. See United States v. Marengo County, supra.

10. Because the at-large election schemes have been

found violative of Section 2, "it is unnecessary for the

Court to reach the constitutional claims presented. That is

especially true here, where the court of appeals indicated

that "[t]he purpose of the remand is to allow the parties to

update the record and to supplement the record with evidence

that might tend to affect [the] finding of discriminatory

results." United States v. Marengo County Commission, supra,

'' at 1574 (emphasis added).

. ...

,.

11. The defendants shall immediately prepare fair

·election plans for the County Commission and County School

Board and file those plans with the Court. These filings

shall be made no later than thirty days from entry of this

decision. Simultaneous with defendants' filings in this

Court, defendants shall seek preclearance of said plans under

Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. 1973. See

~·

McDaniel v. Sanchez, 452 U. S. 130 (1981.) Once the

Section 5 process has been completed, this Court will then

undertake its review of said plans. (Ibid.)

12. Defendants were enjoined in 1984 by this Court

from holding scheduled elections under the at-large system,

and certain of the defendants are holding over in off ice

beyond their terms. The defendants shall also prepare a

schedule for holding el~ctions at the earliest possible date

under the proposed plans and shall submit the proposed election

schedule for Section 5 preclearance at the same time said

plans are submitted.

The Court retains jurisdiction of this matter for

P pu~poses of issuing additional orders as may be appropriate.

J. B. SESSIONS, III

United States Attorney

Respectfully submitted,

~i

HM. BRADFORD REYNOLDS

Assistant Attorney General

.&~- J4__

RALD W. JONES

AUL F. HA.NCOCK

. GERALD HEBERT

CHRISTOPHE~ G. LEHMANN

Attorneys, Voting Section

Civil Rights Division

Department of Justice

lOth and Constitution Ave., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20530

(202) 724-6292

..

"\,

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that a copy of the Proposed Findings

of Fact and Conclusions of Law for the United States was

mailed, postage prepaid, on this ~O~day of June, 1985 t-:; th~

following counsel of record:

Cartledge W. Blackwell, Jr., Esq.

Blackwell and Keith

Post Office Box 592 ·

' Selma, Alabama 36701

Hugh A. Lloyd, Esq.

Lloyd, Dinning and Bo.ggs

Post Office Drawer Z

Demopolis, Alabama 36732

J. L. Chestnut, Jr., Esq.

Chestnut, Sanders, and Sanders

P. o. Box 773

Selma, Alabama 36701

Gerald Hebert

torney, Voting Section

¢ivil Rights Division

_/bepartment of Justice

lOth and Constitution Ave., N. W.

Washington, D. C. 20530