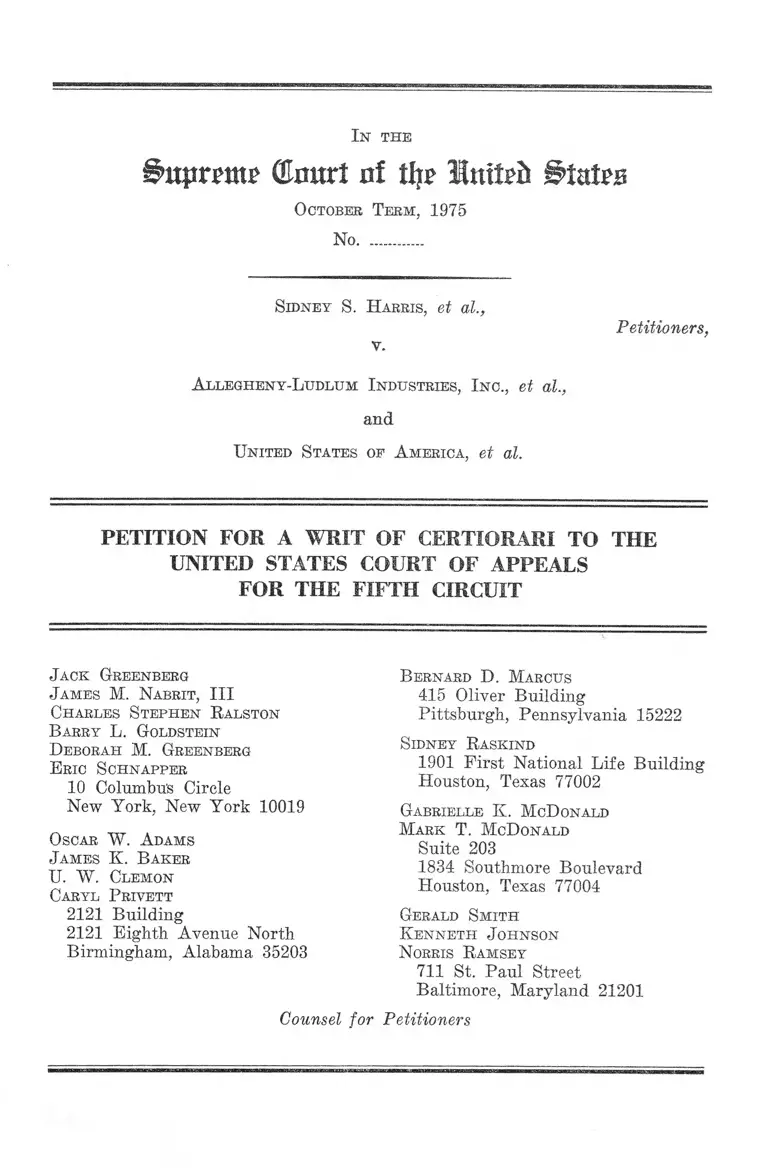

Harris v. Allegheny-Ludlum Industries Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1976

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Harris v. Allegheny-Ludlum Industries Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, 1976. 445f4971-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/caae99b3-9769-4915-a7e6-24a4fce20e52/harris-v-allegheny-ludlum-industries-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-fifth-circuit. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n th e

Qlmtrt at tfjp In t l^ Matm

October Teem, 1975

No.............

Sidney S. H arris, et al.,

v.

Allegheny-Ludlum I ndustries, I nc., et al.,

and

United States of America, et al.

Petitioners,

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Charles Stephen Ralston

Barry L. Goldstein

Deborah M. Greenberg

Eric Schnapper

10 Columbu's Circle

New York, New York 10019

Oscar W. Adams

J ames K. Baker

U. W. Clemon

Caryl P rivett

2121 Building

2121 Eighth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Bernard D. Marcus

415 Oliver Building

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15222

Sidney Raskind

1901 First National Life Building

Houston, Texas 77002

Gabrielle K. McDonald

Mark T. McDonald

Suite 203

1834 Southmore Boulevard

Houston, Texas 77004

Gerald Smith

Kenneth J ohnson

Norris Ramsey

711 St. Paul Street

Baltimore, Maryland 21201

Counsel for Petitioners

Opinions Below ..................... ...... -....—................—...... 1

Jurisdiction ........ ........... ......................... ....—............... 2

Question Presented ........ ................................................ 2

Statutory Provisions Involved ..................... .......... ..... 2

Statement of the Case...... ............................................. 4

Reasons for Granting the Writ ........ 7

1. The Importance of The Issues Involved ___ 7

2. The Proposed Waiver of Future Injunctive

Relief ....................................................... 11

3. The Proposed Waiver of Future Monetary

Relief ....................................... 15

Conclusion .................................................................... 17

A ppendix

Opinion of the District Court, June 7, 1974 _____ la

Opinion of the Court of Appeals, August 18,1975 .. 13a

Opinion of the District Court, January 6, 1976.....120a

Order of the District Court, January 6, 1976.......126a

I N D E X

PAGE

T able op Cases

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975) ..14,16

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36 (1974) 12,

13,14,16

11

Carroll v. Bethlehem Steel Corp. (D. Md., No. M-

75-374) .............. ...........-........-.... -................. .............. 9

Chatman v. United States Steel Corp. (N.D. Cal. No.

0-75-1239) ...... .... .......................................... .. .......... 9

Dickerson v. United States Steel Corp. (E.D. Pa., No.

73-1292) ...... .......................................... ..................- 9

Dickerson v. United States Steel Corp., cert, denied,

421 U.S. 948 (1975) ........ .............. ............ .............. 9

Ford v. United States Steel Corp., 520 F.2d 1043 (5th

Cir. 1975) ............................ ....................... .............. 7

Harris v. Republic Steel Corp. (N.D. Ala. No. 74-

P-3345) .................................................... .................... 9

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, 421 U.S. 454

(1975) ................ ..... ................. .....................-.......-.... 10

Lane v. Bethlehem Steel Corp. (D. Md., No. 71-580-H) 9

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965) ___ 14

Rodgers v. United States Steel Corp. (W.D. Pa. No.

71-793) ________ ________ ___________-.......... -.... 9

Rodgers v. United States Steel Corp., 508 F.2d 152

(3rd Cir. 1975), cert. den. sub nom., United States

Steel Corp. v. Rodgers, 46 L.Ed. 2d 50 (1975) ...... 9

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Ed., 402 U.S.

1 (1971) _____ _______ ____-...... .......-.................... 14

Taylor v. Armco Steel Corp. (S.D. Tex. No. 68-129) 9

United States v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 446 F.2d 652

(2nd Cir. 1971)

PAGE

7

Ill

United States v. Trucking Employers, Inc., (D.D.O.

PAGE

C.A. No. 74-453) ........................ ................................ 10

Waker v. Republic Steel Corp. (N.D. Ala., Nos. 71-

179, 71-180, 71-181, 71-185) ....... .............. ....... .......... 9

Williamson v. Bethlehem Steel Corp. (W.D.N.Y. No.

71-487) ........................................................................ 9

Other Authorities:

In the Matter of the Bethlehem Steel Corp., Decision

of the Secretary of Labor, Docket No. 102-68, Jan.

15, 1973 ............ ..... ..... ........... .... ................................ 7

I n t h e

(Emurt nf IIjt I n M Stairs

October T eem , 1975

No.............

S idney S. H arris, et al.,

v.

Petitioners,

A llegheny-Ludlttm I ndustries, I nc ., et al.,

and

U nited S tates oe A merica, et al.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

The petitioners Sidney S. Harris, et al., respectfully

pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review the judgment

and opinion of the United States Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit entered in this proceeding on August 18, 1975.

Opinions Below

The opinion of the court of appeals is reported at 517

F.2d 826, and is set out in the Appendix, pp. 13a-119a.

The opinion of the district court of June 7, 1974, is re

ported at 63 F.E.D. 1, and is set out in the Appendix, pp.

la-12a. The opinion and order of the district court of

January 6, 1976, which are not reported, are set out in the

Appendix, pp. 120a-127a.

9

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the court of appeals was entered on

August 18, 1975. On November 4, 1975, Mr. Justice Powell

signed an order extending the time for the filing of this

petition until January 15, 1976. This Court’s jurisdiction

is invoked under 28 U.S.C. §1254(1).

Q uestion P resen ted

In this employment discrimination case, did the Court of

Appeals err in holding valid a waiver, executed pursuant

to an industrywide government-employer-union consent

decree, of the right to sue for injunctive relief and back

pay to remedy an employer’s or union’s failure, subsequent

to the decree’s entry, to eliminate continued effects of past

discrimination?

Statutory P rovision s Involved

Section 706(f)(1) of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, as

amended, 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(f) (1):

If a charge filed with the Commission pursuant to

subsection (b) is dismissed by the Commission, or if

within one hundred and eighty clays from the filing of

such charge . . . the Commission has not filed a civil

action under this section . . . or the Commission has

not entered into a conciliation agreement to which the

person aggrieved is a party, the Commission . . . shall

so notify the person aggrieved and within ninety days

after the giving of such a notice a civil action may be

3

brought against the respondent named in the charge

(A) by the person claiming to be aggrieved. . . .

Section 706(g), 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(g) :

If the court finds that the respondent has inten

tionally engaged in or is intentionally engaging in an

unlawful employment practice charged in the com

plaint, the court may enjoin the respondent from en

gaging in such unlawful employment practice, and

order such affirmative action as may be appropriate,

which may include, but is not limited to, reinstatement

or hiring of employees, with or without back pay (pay

able by the employer, employment agency, or labor or

ganization, as the case may be, responsible for the

unlawful employment practice), or any other equitable

relief as the court deems appropriate. . . . No order

of the court shall require the admission or reinstate

ment of an individual as a member of a union, or the

hiring, reinstatement, or promotion of an individual

as an employee, or the payment to him of any back

pay, if such individual was refused admission, sus

pended, or expelled, or was refused employment or ad

vancement or was suspended or discharged' for any

reason other than discrimination on account of race,

color, religion, sex, or national origin or in violation

of section 704(a).

Section 1981, 42 U.S.C.:

All persons within the jurisdiction of the United

States shall have the same right in every State and

Territory to make and enforce contracts . . . as is

enjoyed by white citizens. . . .

4

Statem ent o f the Case

On April 12, 1974, the United States filed this action in

the Northern District of Alabama alleging that nine major

steel companies and the United Steelworkers of America

had engaged in discrimination on the basis of race and

sex. The parties simultaneously presented to the District

Court two lengthy consent decrees which had been agreed

upon by the parties prior to the commencement of the action.

The district judge approved both decrees on the day they

were submitted. The decrees provide for certain injunctive

relief to be administered by an Implementation Committee

at each of several hundred plants and overseen by a na

tional Audit and Review Committee. With the exception

of a single member of the Audit and Review Committee,

every voting member of these committees was appointed

by, and serves at the pleasure of, the defendants. The

decrees also required an offer of payment in lieu of back

pay to most minority employees employed at the plants

involved, conditioned upon the execution of a release of

certain claims under Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act

and other laws. The question presented by this petition

is the permissible scope of the releases which minority em

ployees will be asked to sign.

Petitioners are black steelworkers employed at steel

plants covered by the decrees. Some petitioners are parties

to six Title VII cases pending in several district courts

prior to the filing of this action j1 others have charges pend

ing before the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

(E.E.O.C.). Nine days after the decrees were approved

petitioners moved to intervene for the limited purposes of

attacking the legality of certain provisions of the decrees 1

1 See cases cited, p. 26a, n. 10. Counsel representing- petitioners

are counsel of record in these eases.

5

and restricting the scope of any waiver to be required.

The District Court, after clarifying the decrees in certain

material respects, concluded they were lawful. Pp. la-12a.

The Court of Appeals construed the decrees so as to elim

inate, for the most part, those aspects which petitioners

had claimed were illegal.2 3

Petitioners advanced three objections to the scope of

the proposed waivers. Petitioners urged, first, that the

proposed waivers were invalid to the extent to which they

purported to preclude an employee from suing for addi

tional back pay if the back pay which he received under

the decrees was less than the total compensable economic

loss which he suffered prior to the date the decrees were

entered because of unlawful discrimination by the defen

dants. Both the District Court and the Court of Appeals

construed the release proposed by the signatories to include

such a waiver, and both held such a waiver valid as a rea

sonable compromise of an accrued monetary claim. Pp.

2 The Court of Appeals construed paragraph 19 of decree I to

require that E.E.O.C. not recommend acceptance of the back pay

unless it found, after an individualized investigation, that the

decrees had in fact fully remedied the charging party’s complaint.

Pp. 93a-94a. Paragraph C of the decrees, which petitioners objected

to as requiring the government to oppose any systemic relief

sought in private actions, was held merely to require the govern

ment to suggest that consideration of such actions be deferred

while the government sought to negotiate appropriate relief under

the decrees. Pp. 85a-88a. The Fifth Circuit ruled that the

decrees in no way reduced the information which must be given

to the Office of Federal Contract Compliance, or limited the au

thority of the Secretary of Labor to invoke sanctions if a steel

company engaged in discrimination, Pp. 96a-100a. The Court

of Appeals mooted petitioners’ objection that the decrees did not

require detailed periodic reports to the district court by reading

such a requirement into a directive of the Audit and Review Com

mittee. Pp. 103a-105a. Certain problems remain as to whether

the signatories are complying with the decrees as construed by

the Fifth Circuit, and are the subject of ongoing litigation in the

lower courts.

6

10a-12a, 54a-57a. Petitioners do not seek review of this

aspect of the Fifth Circuit’s decision.

Petitioners further objected that the proposed release

appeared to cover monetary claims for losses occurring

after the entry of the decrees. The District Court’s opinion

did not consider whether this was within the scope of the

proposed waiver or, whether such claims could be relin

quished in advance. The Court of Appeals apparently

understood the proposed release to include such a waiver,

Pp. 57a-64a; it held such a waiver valid subject to a

limitation the precise impact of which is unclear. See p.

15, infra.

Third, petitioners contended that the proposed releases

would be invalid to the fextent that they purported to limit

the right of an employee to sue for necessary injunctive

relief if, despite the decrees, an employer continued to

enforce a seniority system which perpetuated, or otherwise

failed to end, any continuing effects of past discrimination.

The District Court, in its 1974 opinion, made no mention

of the issue. The Court of Appeals’ opinion concluded that

the decrees did not contemplate such an injunctive waiver,

and included certain dicta regarding the validity of such

a waiver, the meaning of which is in dispute.

On remand the defendants urged that the Fifth Circuit

had misconstrued the decrees, and moved to amend the

decrees to include an injunctive waiver. Petitioners op

posed the amendment on the ground that such a waiver

would be invalid and that the amendment was otherwise

improper. The District Court, on January 6, 1976, held

that petitioners were no longer parties to the case, rejected

their renewed motion to intervene, and approved the amend

ment. Pp. 120a-127a. The signatories contended, and

the District Court apparently concluded, that the Fifth

7

Circuit dicta liad indicated that such an injunctive waiver

would be lawful. The District Court then stated it would

entertain a motion to intervene for the purpose of moving

to reconsider the amendment on the narrow ground that

the signatories in 1974 had not in fact agreed to provide

in the decrees for an injunctive waiver. P. 122a. The

January 6, decision, to the extent that it excluded peti

tioners from the case and rejected their contentions that

the amendment was improper as a matter of law, is the sub

ject, of an appeal and petition for writ of mandamus before

the Fifth Circuit. Within 10 days of the January 6 opinion

petitioners intervened in the district court and moved to

set aside the amendment on the narrow ground permitted

by the district court. The consideration of that motion has

been deferred pending discovery as to the intent of the

signatories in 1974.

It is with reg’ard to these second and third objections to

the scope of the proposed release that certiorari is sought.

R easons for G ranting the W rit

1. T he Im portance o f T he Issues Involved

Although the consent decrees deal with a variety of forms

of discrimination, the critical problem in the steel industry

is reform of the seniority system. Prior to the entry of

the decrees, and especially before 1968, most steel plants

operated by the defendant companies maintained segre

gated departments and lines of progression.3 The depart

ments and lines of progression to which blacks were as-

3 See Ford v. United States Steel Corporation, 520 F.2d 1043 (5th

Cir. 1975) ; United States v. Bethlehem Steel Corporation, 446

F.2d 652 (2nd Cir. 1971) ; In the Matter of the Bethlehem Steel

Corporation, Decision of the Secretary of Labor, Docket No. 102-

68, January 15, 1973.

signed were generally limited to poorly paid and un

pleasant jobs. Although this discrimination in initial

assignment has to some extent abated, many minority em

ployees have been unable to transfer into traditionally

white jobs because of the defendants’ seniority system.

Under that system when a vacancy occurs in an all-white

department, applicants from within the department are

given preference over employees from other departments.

Thus if a job were sought by a white within the depart

ment who had worked for the company for only a year,

and by a black from another department who had worked

there for 20 years, the position would be awarded to the

white on the basis of “seniority.” The seniority system

perpetuates in this manner the effect of past discrimina

tion in initial assignment.

Until the seniority system is overhauled so as to elim

inate this special treatment for employees in traditionally

all-white departments, black employees will continue to

earn less than whites solely on account of their race. The

consent decrees required certain changes in seniority sys

tems, and contemplated further negotiations among the sig

natories with regard to seniority; whether, as petitioners

contend, the decrees are unlikely to produce meaningful

reforms of the seniority systems is a question whose an

swer will not be known for several years. The parties pro

pose that, as a condition of receiving a lump sum in 1976,

more than 40,000 minority employees sign a waiver which

provides that, to the extent that the government is unable

or unwilling to negotiate reform of the seniority system

under the consent decrees, those employees will be locked

into their predominantly black departments for the rest of

their lives, unable to seek in any federal or state court in

junctive relief to reform that system or monetary compen

sation for the loss they may sutler in the years to come.

9

The District Court correctly recognized that it was of

paramount importance to sound judicial administration

that, before any waivers be solicited from such a large

group of employees, there be a definitive judicial decision

as to the permissible scope of the release. If that question

is not finally resolved in the instant case, it will have to

be relitigated every time an employee who signed a waiver

brings an action alleging* that the seniority system at his

plant perpetuates the effect of past discrimination in as

signment. The validity of the contested aspects of the

waivers will also affect whether employees who sign them

will remain as class members in the numerous private class

actions now pending against the defendant companies. Thus

the circulation and execution of waivers in plants covered

by such class actions will necessarily give rise to a com

plex round of litigation as to class membership in all such

actions.4 The mere proposal to solicit such waivers has

already spawned two petitions for writs of certiorari in

such private actions;5 * the impact of the actual execution

of such waivers will be substantially greater. Under the

decrees waivers will be sought in plants in over 40 districts

in ten different circuits. A definitive decision by this Court

as to the permissible scope of a waiver of Title YU rights

will, as a practical matter, substantially reduce the volume

4 The cases in which that issue would have to be resolved include

Harris v. Republic Steel Corp., No. 74-P-334-S (N.D. A la.); Waker

v. Republic Steel Corporation, Nos. 71-179, 71-180, 71-181, 71-185

(N.D. A la.); Dickerson v. United States Steel Corp., No. 73-1292

(E.D. Pa.) ; Rodgers v. United States Steel Corp., No. 71-793 (W.D.

Pa.); Carroll v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., No. M-75-374 (D. Md.) ;

Lane v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., No. 71-580-H (D. Maryland) ;

Williamson v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., No. 71-487 (W.D.N.Y.) ;

Chatman v. United States Steel Corporation, No. C-75-1239 (N.D.

Cal.); Taylor v. Armco Steel Corp., No. 68-129 (S.D. Tex.).

5 Rogers v. United States Steel, cert. den. 46 L.Ed. 2d 50 (1975) ;

Dickerson \. United States Steel, cert. den. 421 U.S. 948 (1975).

10

and scope of litigation produced by the solicitation of

waivers from tens of thousands of employees.

Such a decision by this Court is also necessary to estab

lish guidelines for the government in other cases. The

Department of Justice and the E.E.O.C. enter each year

into a substantial number of consent decrees and more

than 5,000 conciliation agreements which generally involve

some form of waiver. The type of waiver agreed to varies

from the sweeping prospective release in the instant case

to a more narrow release of accrued money claims such

as used in the nationwide trucking consent decree.6 These

differences reflect differing responses by government attor

neys to efforts by negotiators for companies and unions to

turn such decrees or agreements into devices to impede or

thwart private litigation. The thrust of such efforts is to

defeat the intent of Congress that the remedies provided

to employees and to the government remain independent

and complementary. Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415

U.S. 36, 47-48 (1974). See, Johnson v. Railway Express

Agency, 421 U.S. 454 (1975). Petitioners maintain that

here, as in other eases,7 the government has gone too far

in acceding to employer and union demands that a con

sent decree be used in this manner. To the extent that the

Court of Appeals has also erroneously accepted the sweep

ing waiver sought by the defendants, it has sanctioned a

concession which the government will be hard pressed to

withhold in subsequent cases. That error will, unless cor

rected by this Court, have ramifications far beyond this

particular case.

These problems, arising as they must in federal courts

throughout the country, require the definitive nationwide

6 United States v. Trucking Employers, Inc., C.A. No 74-453

D.D.C.

7 See pp. 55a-58a, n. 30.

11

resolution which, only this Court can provide. Even within

the Fifth Circuit the decision of the Court of Appeals has

failed to clearly resolve the questions presented by this

petition. The Fifth Circuit’s decision sanctioned a release

as to the “continuing effects of past discrimination” and

ruled unlawful any release with regard to post-decree acts

of discrimination, but left in doubt whether a company’s

future failure to reform its seniority system to end such

continuing effect would itself constitute a new act of dis

crimination. See pp. 57a-64a. The latter question is of

critical importance to both this case and a substantial

segment of American industry. The disagreement among

the parties as to the proper construction of the Fifth Cir

cuit’s decision became apparent four months after that

decision when the defendants moved to amend the decrees

to provide for an injunctive waiver, arguing that an em

ployee could waive in advance his right to sue to reform

the seniority system since, in defendant’s view, the future

application of such a system would not constitute a new

act of discrimination. The questions posed by the proposed

waiver of future monetary and injunctive relief are too

important to the other related pending cases, to govern

ment policy, and to the tens of thousands of minority

employees in the steel industry, to be left in the ambiguous

state created by the decision of the Court of Appeals.

2. T he P roposed W aiver o f Future Injunctive R elief

Whether the defendants, prompted by the consent de

crees, will in fact reform their seniority systems to permit

blacks to compete for promotions on an equal basis with

whites is, as of now, a matter of conjecture. The consent

decrees in this regard constitute a framework for further

negotiation between counsel for the government, the em

ployers, and the union. Many critical areas, such as the

merger of departments and lines of progression, are ex-

12

pressly reserved as subjects for further discussion on a

plant by plant basis. Pp. 104a-05a. The provisions of both

decrees are to be reconsidered by the signatories in

1976. It cannot now be foreseen whether, in the years

ahead, the substantive provisions of the decrees, together

with such further concessions as the government can exact,

will, in any particular plant, eliminate the discriminatory

aspects of the pre-decree seniority system.

The parties propose that, as a condition of receiving a

payment in lieu of back pay under the decrees, the release

required of each employee include a waiver of his right to

sue for necessary injunctive relief if the seniority system

is not fully reformed. P. 126a. Should a minority em

ployee sign such a waiver and subsequently discover

that he is still locked into a poorly paid all-black depart

ment, he will have no right to sue. At a plant where the

decrees are generally ineffective, a whole generation of

black workers would, for the rest of their careers, be rele

gated to the jobs to which they were initially assigned on

the basis of race. Although the consent decrees can be

vacated on the motion of any signatory in 1979, the waivers

remain binding for the indefinite future. The signatories

insist that, even if a court should at some future date hold

a seniority system illegal because it perpetuates the effect

of pre-decree discrimination, the employer would be free

to apply that illegal system to any employee who had

signed an injunctive waiver.8 Such a release is not a

compromise of accrued claims, it is a license to break the

law.

In Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36 (1974)

an aggrieved employee, prior to commencing a Title YII

action, sought arbitration under a procedure which pro-

8 Transcript of Hearing of January 2, 1976, pp. 26-30; 34-35.

13

vided that it would be “final and binding upon the Com

pany, the Union, and any employee or employees involved”.

415 U.S. at 42. The arbitrator found there was no racial

discrimination, and the employer argued that the employee,

by submitting his claim to binding arbitration, had waived

his rights to sue under Title YII. This Court held:

We are also unable to accept the proposition that peti

tioner waived his cause of action under Title YII. To

begin, we think it clear that there can be no prospec

tive waiver of an employee’s rights under Title YII

. . . Title VII’s strictures are absolute and represent

a congressional command that each employee be free

from discriminatory practices . . . In these circum

stances, an employee’s rights under Title VII are not

susceptible of prospective waiver. 415 U.S. at 51-52.

The waiver in Alexander was prospective in that, although

the disputed employer conduct occurred before the pur

ported waiver, the employee committed himself in advance

to obtaining only so much relief as the arbitration would

thereafter award. The holding of Alexander applies a

fortiori to the waiver proposed in this case. Not only is

an employee asked to limit himself to such seniority relief

as the government chooses to negotiate for him, the em

ployee is asked to do so with regard to seniority problems

which, as a result of unforeseeable patterns of vacancies,

layoffs, and attrition, may only arise several years in the

future.

Respondents seek to avoid the obviously prospective

nature of such a waiver by asserting that the only “act of

discrimination” was the creation prior to 1974 of black

and white departments and that the application of a rule

which gives preference to employees of the all-white depart

ment is not an “act of discrimination”, but merely a “eon-

14

tinued effect of past discrimination.” Since the “discrimina

tion” occurred in the “past”, respondents reason that the

waiver is retrospective even when applied to events tran

spiring in 1980 or later. But Alexander cannot be distin

guished by such semantic sleight of hand. No court in the

land would uphold releases signed by the parents of school

age children purporting to relinquish their right “to elim

inate from the public schools all vestiges of state imposed

segregation.” Swann v. Charlotte-M ecldenburg Board of

Education, 402 U.S, 1, 15 (1971). Nor would this Court

enforce a waiver signed by a citizen denied the right to

vote which contained language abandoning the right to

judicial relief which would “so far as possible eliminate the

discriminatory effects of the past as well as bar like dis

crimination in the future.” Louisiana v. United States, 380

U.S. 145, 154 (1965); see, Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody,

422 U.S. 405, 418-19 (1975). The proposed waiver of the

right to sue for injunctive relief is no different; to the

extent the Court of Appeals approved such a waiver its

opinion is in conflict with the decision of this court in

Alexander.

The respondents maintain, and the district court appar

ently concluded, that the Fifth Circuit held that such an

injunctive waiver would be valid.9 Petitioners believe the

Court of Appeals’ decision is ambiguous as to whether, and

if so when, a defendant’s failure to reform a seniority sys

tem which perpetuated the effect of past discrimination

would itself constitute a new “act of discrimination” relief

from which, under the Fifth Circuit’s opinion, could not

be waived. Pp. 60a-64a. As is more fully set out in the ac

companying Motion to Defer Consideration, whether the re

lease to be required of employees should include an injunc

tive waiver is still the subject of proceedings in both the

See Transcript of Hearing of January 2, 1976, pp. 49-53.

15

District Court and Court of Appeals. For this reason peti

tioner would suggest that consideration of this petition be

postponed until the lower courts have finally decided

whether to permit the inclusion of such an injunctive

waiver.

3. T he P roposed W aiver o f Future M onetary R elief

In return for the back pay to be offered under the con

sent decrees, the defendants propose that the release re

quired from each employee waive his monetary claims “for

damages incurred at any time because of continued effects

of complaint or decree-covered acts or practices which took

place on or before the entry date of the consent decrees.” 10

P. 57a. The Court of Appeals held that minority em

ployees could compromise in this manner their back pay

claims for financial loss which occurred prior to the date

of the consent decrees, April 12, 1974. Pp. 64a-81a. Peti

tioners do not seek review of this aspect of the Fifth Cir

cuit’s decision. Petitioners maintain, however, that the

Court of Appeals erred insofar as11 it approved the use of

a release which would waive an employee’s right to sue for

financial loss which occurs after the entry of the consent

decrees because of the defendant’s failure to end the con

tinuing effects of past discrimination.

A waiver of back pay claims which will accrue at some

future date is a prospective waiver forbidden by this

10 Paragraph 18(c) of consent decree I proposes that the release

“bar recovery of any damages suffered at any time after the date

of entry of this decree by reason of continued effects of any such

discriminatory acts which occurred on or before the date of entry

of this Decree”. P. 55a. (Emphasis added) 11

11 It is unclear at what point, if any, a defendant’s failure to

end such continuing effects would constitute a new “act of dis

crimination” for which back pay could be sought. See pp. 13-14.

The actual release approved by the District Court contained no

limitation of this sort on the prospective monetary waiver.

16

Court’s decision in Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415

U.S. 36 (1974). See p. 13, supra. Such, a prospective

waiver of Title VII rights is also inconsistent with Albe

marle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975). Back pay

is mandated in Title VII cases, not merely to make an

employee whole for any violation of his rights, but also

to deter an employer or union from failing to correct em

ployment practices which discriminate or continue the

effects of past discrimination.

If employers faced only the prospect of an injunctive

order, they would have little incentive to shun prac

tices of dubious legality. I t is the reasonably certain

prospect of a back pay award that “provide [s] the

spur or catalyst which causes employers and unions

to self-examine and to self-evaluate their employment

practices and to endeavor to eliminate, so far as pos

sible, the last vestiges of an unfortunate and ignomin

ious page in this country’s history.” 422 U.S. at 417-18.

The critical question in the steel industry is whether the

employers and union will modify the seniority system so

that the pre-decree discriminatory assignment of a genera

tion of blacks to all-black and poorly paid departments

will not have a continuing discriminatory impact on those

blacks in the years ahead. Should minority employees

execute the proposed waivers they would have the effect,

if valid, of removing any financial incentive for the steel

companies and union to reform that seniority system. If

the companies and union are rendered immune from such

liability, the spur for reform contemplated by Title VII

would be vitiated. To the extent that the Court of Appeals

approved such a prospective waiver of monetary relief, its

decision is inconsistent with the decisions of this Court, in

Alexander and Moody.

17

CONCLUSION

For the above reasons a writ of certiorari should issue

to review the judgment and opinion of the Fifth Circuit.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

Charles S teph en R alston

B arry L. Goldstein

D eborah M. Greenberg

E ric S chnapper

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Oscar W , A dams

J ames K . B aker

U. W. Clemon

Caryl P rivett

2121 Building

2121 Eighth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

B ernard D. Marchs

415 Oliver Building

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15222

S idney R askind

1901 First National Life Building

Houston, Texas 77002

Gabrielle K . M cD onald

Mark T. M cD onald

Suite 203

1834 Southmore Boulevard

Houston, Texas 77004

Gerald S m ith

K enn eth J ohnson

N orris R amsey

711 St. Paul Street

Baltimore, Maryland 21201

Counsel for Petitioners

A P P E N D I X

l a

O p in ion o f th e D istric t C ourt, Ju n e 7, 1 9 7 4

U nited S tates of America, By William B. S axbe, the At

torney General, on Behalf of Peter J, Brennan the

Secretary of Labor, and the Equal Employment Op

portunity Commission,

Plaintiff,

v.

A llegheny-Ludlum I ndustries, I nc ., et al.,

Defendants.

Civ. A. No. 74-P-339-S

United States District Court

N. D. Alabama, S. D.

June 7, 1974

Robert T. Moore, Dept, of Justice, William L. Robinson,

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, William J.

Kilberg, Sol. of Labor, Dept, of Labor, Washington, D. C.,

for plaintiff.

Ralph L. McAfee, Cravath, Swain & Moore, New York

City, William K. Murray and James R. Forman, Jr.,

Thomas, Taliaferro, Forman, Burr & Murray, Birmingham,

Ala., for defendant Companies.

Michael H. Gottesman, Washington, D. C., Jerome A.

Cooper, Cooper, Mitch & Crawford, Birmingham, Ala., for

defendant Steelworkers.

Judith A. Lonnquist, NOW, Chicago, 111., Jack Green

berg, New York City, Oscar W. Adams, Jr., Adams, Baker

& Clemon, Birmingham, Ala., Gerald A. Smith, Baltimore,

2a

Md., Bernard D. Marcus, Kaufman & Harris, Pittsburgh,

Pa., Arthur J. Mandell, Mandell & Wright, Houston, Tex.,

William E. Jones, NAACP, New York City, J. Richmond

Pearson, Birmingham, Ala., for petitioners for interven

tion.

Memorandum of Opinion-

P ointer, .District Judge.

After months of negotiations pursuant to the govern

mental conciliation function of Title VII, 42 TJ.S.C.A.

§ 2000e et seq., the parties herein reached a tentative agree

ment as to a manner and means for correcting allegedly

discriminatory employment practices of a systemic nature

at some 240 steel plants and other steel-related facilities

throughout the nation. The agreement was reduced to

writing in the form of two consent decrees entered into by

the United States, through various governmental agencies

including the Justice Department, the Labor Department

and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, as

plaintiff, and by nine steel companies and the United Steel

workers of America, as defendants. The proposed decrees

were presented to, and entered by, this court on April 12,

1974, resulting in a broad national settlement of Title VII,

and related, disputes between the United States and the

ten defendants. The provisions reflect a thoughtful and

earnest attempt to respond to—and to reconcile competi

tion between—charges of employment discrimination made

on behalf of black, female, and Spanish surnamed workers

and applicants.

Consent Decree I takes the form of an injunction with

respect to those matters which, in general, have previously

been affected by collective bargaining between the com-

Opinion of the District Court, June 7, 1974

3a

parties and the union. The decree provides for a restruc

turing of seniority rules and regulations, primarily using

plant continuous service as a base; specifies procedures

respecting transfers, promotions, vacancies, layoffs and

recalls; and enumerates affirmative action guidelines and

goals with respect to trade and craft positions and initial

selection and assignment of employees. In recognition that

general standards may require tailoring to meet local

problems and that experience may indicate the inadequacy

of some of the remedial steps, implementation procedures

and enforcement tools are established through a structure

of Implementation Committees, composed of company,

union and minority members, at each affected facility, as

well as an Audit and Review Committee which is national

in scope. A mechanism for expeditious and co-ordinated

resolution of the multitude of pending EEOC charges re

specting these defendants is established. A potential back

pay fund of $30,940,000.00 is created, along with guidelines

for calculating and disbursing awards to electing indi

vidual employees affected by past discrimination. Juris

diction is retained by the court for a period of at least five

years.

Consent Decree II takes the form of a general injunc

tion respecting those aspects of employment which are, es

sentially, company-controlled and not normally subject to

collective bargaining agreements. The companies are gen

erally enjoined from any form of employment discrimina

tion and are obligated to institute a program of affirmative

action with respect to hiring, initial assignments, and man

agement training programs, as well as affirmative recruit

ment of minorities. See Morrow v. Crisler, 491 F.2d 1053

(CA5 1974); Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 495

F.2d 398 (CA5 June 3, 1974). The court retains jurisdic

Opinion of the District Court, June 7, 1974

4 a

tion for at least five years; and, as also is true regarding

Consent Decree I, the consent decree between the govern

ment and the defendants does not purport to bind any

individual employee or to prevent the institution or mainte

nance of private litigation.

Shortly after entry of these decrees, various individuals

and organizations sought to intervene. A hearing was set

for May 20, 1974, with the request that briefs be filed by

May 13th and reply briefs by the hearing date. This memo

randum is addressed to the claims for intervention and

certain other issues raised thereby and is issued after a

study of the motions, briefs, reply briefs, and oral argu

ment presented at the May 20th hearing.

I ntervention

The court concludes that §§ 707(e) and 706 of Title VII,

42 U.S.C.A. §§ 2000e-6(e) and 2000e-5, confer upon some

petitioners a right to intervene within the meaning of Rule

24(a)(1), F.R.Civ.P. This statutory right is provided to

a “person or persons aggrieved” within the meaning of

Title VII. In this context, the term refers to those in

dividuals with respect to whom alleged discrimination by

the defendants is within the scope of a charge which has

heretofore been presented to the EEOC, without regard

to whether such charge was filed by them, by fellow em

ployees with similar complaints, by an organization on

their behalf, or by a member of the EEOC, and without

regard to whether or not they are named plaintiffs or actual

or putative class members in pending litigation.

Most of the individual petitioners—including some who

joined in the petitions of the Ad Hoc Committee and of the

Opinion of the District Court, June 7, 1974

5a

National Organization of Women1—meet the test for inter

vention of right under Rule 24(a)(1) as just stated. The

court concludes that the balance of the individual peti

tioners—including one who is the principal officer of the

Rank and File Committee, the other organizational peti

tioner—should also be allowed to intervene, given the

rather limited purpose for which intervention is being

allowed, under the provisions of Rule 24(a) (2) or 24(b) (2).

The court denies the requests for intervention by the

three organizations, the Ad Hoc Committee, NOW, and the

Rank and File Committee. While such organizations may

have authority to file charges with the EEOC and even to

file lawsuits with respect thereto, they are not “persons

aggrieved” for the purpose of any statutory right of inter

vention under Rule 24(a)(1). In view of the allowed inter

vention of officers or members of such organizations, it

appears that adequate representation is being afforded for

any interest the organizations may have. See Rule 24(a) (2)

and Hines v. Rapides Parish School Board, 479 F.2d 762

(CA5 1973). Nor, indeed, have the organizations demon

strated a sufficient interest qua organizations to justify the

additional problems of management and inconvenience

caused by unnecessary intervenors. See Bennett v. Madison

County Board of Education, 437 F.2d 554 (CA5 1970);

Horton v. Lawrence County Board of Education, 425 F.2d

735 (CA5 1970). 1 *

Opinion of the District Court, June 7, 1974

1 On May 20, NOW was given leave, essentially nunc pro tunc,

to amend its pleadings, which were filed only on behalf of the

organization, to name not more than three individual women who

were to be allowed to intervene pursuant to Rule 24(a) (1) or (b).

Such amended pleadings were filed with the court on June 4, 1974.

Such intervention as is allowed is permitted at this time2

for the limited purposes of seeking to stay or vacate the

consent decrees and to question the contemplated releases

of hack-pay claims in connection with the payments of hack-

pay to electing employees under the decree. "While the inter-

venors are to he hound hy the decision made with respect

to such limited issues, the court does not consider that such

intervenors, or any class which they may represent, are at

present hound, as a matter of res adjudicata or collateral

estoppel, to the terms of the consent decrees themselves.

No evidentiary hearings are needed with respect to the

issues on which intervention has been allowed. Based upon

responses by counsel to questions posed hy the court at the

May 20th hearing, it is clear that any additional hearings

would merely involve an attempt by intervenors to demon

strate in greater detail the alleged deficiencies and prob

lems presented by the decrees, e. g., that the decrees are

somewhat open-ended and that there may he already some

understandings or proposals as to the manner in which

such details will he resolved.3 There was no indication,

however, that any evidence would be tendered respecting

the basic allegations against the decrees which are not

apparent upon the record. Moreover, time weighs heavy

in this dispute, for not only must implementation go for

ward to meet timetables in the decree, but also delay would

2 This is without prejudice to the rights of individuals to seek

further intervention, in accordance with the ruling's herein, re

specting specific questions which have arisen or may arise in the

future. See Hine’s v. Rapides Parish School Board, 479 F.2d 762

(CA5 1973). The limitation upon present intervention is placed

so that the resolution of the fundamental questions will not be

delayed by disputes over matters which, in essence, are details.

3 See note 2 supra.

Opinion of the District Court, June 7, 1974

7a

adversely affect many of the admittedly prophylactic pro

visions of the decrees to the detriment of the beneficiaries

of Title VII. As the court is convinced that the suggested

evidence would not materially contribute to the resolution

of the limited issues upon which intervention has been

allowed, there is no sound reason to schedule an evidentiary

hearing.

Opinion of the District Court, June 7, 197A

A lleged I llegality oe Consent Decree

Intervenors attack the consent decree on various grounds

of alleged illegality, including vagueness; venue deprival;

lack of advance notice; enforcement by violators; insuffi

ciency of relief ; direct interference with rights of indi

viduals to file, maintain or pursue individual remedies; and

a renunciation of statutory responsibility by executive

agencies.

Without here separately listing the considerations in

volved in each of these thrusts, the court concludes that,

as attacks on the decrees as a whole, they are due to be

denied and overruled, and that the intervenors do not

demonstrate or suggest anything illegal, improper or funda

mentally unsound in these decrees, which, it should be em

phasized, are not binding on individual employees.

By undertaking to resolve by settlement the myriad of

problems regarding employment discrimination in the steel

industry—discussions to which individual employees and

their supporting organizations were not privy—the execu

tive agencies have not renounced their statutory responsi

bilities as alleged. Such efforts are consistent, not incon

sistent, with the statutorily mandated duty of conference,

conciliation and persuasion embodied in Title VII. It more

8a

over appears that the commitment4 * undertaken by the

government with respect to pending or future Title YII

litigation involving these defendants does not preclude the

government from advocating, and bringing expeditiously

into court if a satisfactory resolution is not accomplished

through the settlement procedures established, a claim for

other relief by an aggrieved employee.

The court does recognize that these decrees may, as a

practical matter, impede, if not impair, some interests of

private litigants. Indeed, it must be assumed that conces

sions during settlement negotiations were motivated in part

by the desire of the parties to avoid, by anticipatory cor

rections, future litigation and to provide more expeditious

solutions even in matters already in the judicial processes.

Justice delayed may, it is said, be justice denied. More

over, it must be kept in mind that resolution in this forum

of issues between the government and the defendants does

not preclude additional—or even inconsistent—relief in

favor of private parties in other litigation. As stressed by

Congress in the passage of Title YII and its amendments,

settlement offers the principal hope for rapid correction

of the ills of employment discrimination, preserving, how

ever—as here—the right to litigate where the persons

aggrieved are not parties to the conciliation agreement and

believe the settlement to be unsatisfactory.

4 A letter from the original parties herein was received by the

court on June 3, 1974. Such has been filed on record as it serves

to clarify the obligations of the United States with respect to future

action pursuant to the consent decrees. Nor would it be sound to

assume that the government can not oppose relief sought by a

private litigant: for example, if a particular black plaintiff, due

to his own situation, were to seek an occupational seniority rule

considered by the EEOC to be generally adverse to the interests

of other black employees, it could hardly be asserted that the

EEOC is bound to advocate such relief.

Opinion of the District Court, June 7, 1974

9a

Some of the wording of the consent decrees may on its

face improperly affect the maintenance of private actions.

For example, the decrees provide for mailing of back-pay

notices even to those involved in pending litigation as

named plaintiffs or as determined or putative class mem

bers. In view of the court’s retained powers and in. view

of the presence of the parties to this litigation before other

forums, such problems, as they are identified, can be sat

isfactorily resolved, and no doubt there will be a need

from time to time for liaison and co-ordination between this

court and other forums. The decrees may require clarifica

tion in some particulars and, indeed, as administration of

the decrees continues, there will doubtless be problems

which were not considered or anticipated by the parties or

which run counter to their expectations during negotia

tions. Should such eventualities occur, the court, by virtue

of paragraph 206 of Consent Decree I and paragraph 26

of Consent Decree II, has jurisdiction of this cause for

the purpose of issuing subsequent orders, consistent with

principles of due process, as necessary to further the pur

poses and objectives of these decrees.7

6 "20. Retained Jurisdiction—The court hereby retains jurisdic

tion of this cause for the purpose of issuing any additional orders

or decrees needed to effectuate, clarify or enforce the full purpose

and intent of this Decree.

Anytime after the conclusion of five (5) years from the date of

this decree, any party may move to dissolve this decree in whole

or in part.”

6 “2. The court hereby retains jurisdiction of this cause for the

purpose of issuing any additional orders or decrees needed to

effectuate, clarify or enforce the full purpose and intent of this

decree and/or the agreement attached hereto.

Anytime after the conclusion of five (5) years from the date of

this decree, any party may move to dissolve this decree in whole

or in part.”

7 By leters of June 3, 1974, referred to in note 4 supra, the

original parties herein have stated that all parties accept the

Opinion of the District Court, June 7, 1974

10a

The court finds nothing illegal respecting the consent

decrees themselves, neither in the basic axjproach to settle

ment reflected therein, the way in which such were negoti

ated and entered, nor the manner in which such will be

implemented. Parenthetically, the court notes that the sug

gestion that advance notice was a requirement for the

decree—which does not rise to the status of a class action

decree—would likely haunt, if adopted by the court, the

intervenors and their sponsoring organizations in other

litigation. Cf. Eisen v. Carlisle & Jacquelin, 42 U.S.L.W.

4804, ----- U.S. ------, 94 S.Ct. 2140, 40 L.Ed.2d 732 (May

28, 1974).

A lleged I llegality oe B ack-P ay R elease

In connection with the claim of illegality, some inter

venors have raised the question of the binding effect of a

release executed by employees who accept back-pay under

the decree. The consent decree, however, while providing

for the use of such a release, does not contain a judicial

finding or conclusion that such could be efficacious. This is

an issue in which all parties have an interest and, as a

practical matter, is in need of a present resolution. The

basic question is whether a signed release in exchange for

the payment of back-pay determined under a settlement

Opinion of the District Court, June 7, 1974

court’s view of authority to review any action taken pursuant to

the decrees, including actions of the Audit and Review Committee,

whether or not any party requests such review. Also, such parties,

while perhaps disagreeing with the court as to the limits involved,

acknowledge the concept of retained jurisdiction with respect to

the effectuation of the full purpose of the decrees. Notwithstanding

any such disagreement with the court’s view of such powers, the

parties advised the court “that none of them wishes to cancel or

revoke its consent or withdraw from the Consent Decrees in the

above-captioned case.”

11a

procedure, as contemplated in paragraph 18(g) of Consent

Decree I, can be valid as a matter of public policy.

Intervenors cite, among other similar decisions, Schulte

v. Gang!, 328 U.S. 108, 66 S.Ct. 925, 90 L.Ed. 1114 (1946),

an FLSA case, for the proposition that such a release

would be invalid as contravening public policy. Such FLSA

cases are, however, distinguishable from the instant case.

Relief under the FLSA is defined, 29 U.S.C.A. § 216(c),

while Title YII relief is more flexible, 42 U.S.C.A. § 2000e-

5(g). While the amount of back-pay for an FLSA viola

tion is, essentially, a matter of simple calculation subject

only to the statutory requirements of the Act, Title VII

back-pay awards are much more difficult of ascertainment

as such are subject to innumerable variables. Schulte

seems to be most concerned with the leverage afforded em

ployers if employees could be persuaded or coerced into

waiving statutory pay minimums.

The legislative history of Title VII, as well as the Act

itself in providing substantial mechanisms for conciliation

and settlement, 42 U.S.C.A. §§2000e-5(b) and (f), indi

cates a Congressional desire for out-of-court settlement

of Title VII violations.

In Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 42 U.S.L.W. 4212,

4219, 415 U.S. 36, 94 S.Ct. 1011, 39 L.Ed.2d 147 (1974) the

Supreme Court indicates that there presumably may be

an effective release of Title VII claims where the parties

enter into a voluntary settlement. For such a waiver to

be effective, however, the employee’s consent to the set

tlement must be both “voluntary and knowing”. Id. at 4219

n. 15, 415 U.S. 52, 94 S.Ct. 1021, 39 L.Ed.2d 147. See also

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494 F.2d 211 at

notes 152 and 156a (CA5 1974), in which the Fifth Circuit

Opinion of the District Court, June 7, 1974

12a

seems to indicate its approval of voluntary settlement of

similar issues.

This court concludes that there can he a legal waiver

of hack-pay claims where, for valuable consideration, a

release is signed knowingly and voluntarily, with adequate

notice which gives the employee full possession of the

facts. Such a ruling, however, is not to be taken as a pro

spective ruling on the question of the efficacy of any par

ticular release, as such would require an individual de

termination of the factual setting in which such a release

may he executed.

Conclusion

For the reasons indicated, the court has allowed inter

vention by the individual petitioners for the limited pur

poses of seeking to stay or vacate the consent decrees and

of challenging the legal efficacy of settlement releases of

back-pay claims and has denied the claims of such inter-

venors with respect thereto. Intervention by other peti

tioners or for other purposes has, at present, been denied.

By separate document, the order of the court with respect

to such matters is filed concurrently herewith.

O pin ion o f th e D is tr ic t C o u rt, J u n e 7r 1974

13a

O p in ion o f th e C ourt o f A ppeals, A ugust 18, 1975

U nited S tates op A merica, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

v.

A llegheny-Ludlum I ndustries, I nc., et al.,

Defendants-Appellees,

S idney S. H arris, et al.,

Intervenors-Appellants,

N ational Organization F or W omen, I nc., et al.,

Movants-Appellants.

No. 74-3056

United States Court of Appeals -

Fifth Circuit

Aug. 18, 1975

Oscar W. Adams, Jr., Birmingham, Ala., Kenneth L.

Johnson, Baltimore, Md., Bernard D . Marcus, Pittsburgh,

Pa., Arthur J. Mandell, G-abrielle K. McDonald, Mark T.

McDonald, Houston, Tex., J. Richmond Pearson, Birming

ham, Ala., Nathaniel R. Jones, NAACP, New York City,

for S. S. Harris and others.

Judith A. Lonnquist, Chicago, 111., Kenneth L. Johnson,

Emily M. Rody, Baltimore, Md., Jack Greenberg, James

M. Nabrit, I I I , Barry L. Goldstein, New York City, for

National Organization for Women and others.

O pinion o f the C o u rt o f A p p e a ls , A u g u s t 18, 1975

William J. Kilberg, Sol. of Labor, U. S. Dept, of Labor,

Washington, D. C., Wayman G. Scherrer, U. S. Atty., Bir

mingham, Ala., Leonard L. Scheinholtz, Pittsburgh, Pa.,

Eobert T. Moore, U. S. Dept, of Justice, Washington, D. C.,

Francis St. C. O’Leary, Pittsburgh, Pa., William A. Carey,

Gen. Counsel, William L. Eobinson, Joseph T. Eddins,

EEOC, Washington, D. C., for U.S.A. and Wheeling-Pitts-

burgh Steel Corp.

William K. Murray, James E. Forman, Jr., Birmingham,

Ala., for U. S. Steel Corp., Allegheny-Ludlum Industries,

Eepublic Steel, Youngstown Corp., Bethlehem Steel, Wheel-

ing-Pittsburgh Steel, Armco Steel, National Steel, Jones-

Laughlin.

Michael H. Gottesman, Washington, D. C., Jerome

Cooper, Birmingham, Ala., for Steelworkers.

Carl B. Frankel, Asst. Gen. Counsel, United Steelworkers

of America, Pittsburgh, Pa., Marshall Harris, Asso. Sol.

Labor Eelations, Civ. Eights, Dept, of Labor, Washington,

D. C., Vincent L. Matera, Pittsburgh, Pa., for U. S. Steel

Corp.

Ealph L. McAfee, New York City, for Bethlehem Steel.

David Scribner, New York City, James H. Logan, Pitts

burgh, Pa., Elizabeth M. Schnieder, Doris Peterson, Center

for Constitutional Eights, New York City, for amici curiae.

Appeals from the United States District Court for the

Northern District of Alabama.

Before T hobjstberry, M organ and Clark, Circuit Judges.

T hornberry, Circuit Judge:

These appeals present novel and important issues which

require us to consider the scope of the federal government’s

15a

authority to encourage and negotiate expeditious and effi

cient settlement of widespread charges of employment dis

crimination in the nation’s steel industry. Some of these

issues are procedural in nature; others call into question

the substantive legality of the means utilized. Some issues

are ripe for decision; others are essentially hypothetical

and conjectural. During the interim between the oral argu

ment of these appeals in December, 1974 and the present,

we have carefully examined the attacks which have been

advanced against the settlement. Our conclusion is that the

settlement has not been shown to be in any respect unlawful

or improper, and hence its terms, conditions, and benefits

must go forward immediately in their entirety.

I. I ntroduction and B ackground

On April 12, 1974, a complaint was filed in the federal

district court for the Northern District of Alabama. The

plaintiffs were the United States, on behalf of the Secre

tary of Labor, and the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission. Nine major steel companies1 and the United

Steelworkers of America were named as defendants. The

suit involved some 240-250 plants at which more than

300,000 persons are employed, over one-fifth of whom are

black, Latin American, or female. Alleging massive pat

terns and practices of hiring and job assignment discrim

ination on the bases of race, sex, and national origin, the

1 The companies are Allegheny-Ludlum Industries, Inc., Armeo

Steel Corporation, Bethlehem Steel Corporation, Jones and Laugh-

lin Steel Corporation, National Steel Corporation, Bepublic Steel

Corporation, United States Steel Corporation, Wheeling-Pittsburgh

Steel Corporation, and Youngstown Sheet & Tube Company. Ac

cording to one estimate, the complaint reached seventy-three per

cent of the country’s basic steel industry. Brief for the appellee

steel companies at 3 n. 2.

Opinion of the C o u rt of A p p e a ls , A u g u s t 18, 1975

16a

complaint sought to enforce the edicts of Title YII of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e

et seq., and contractual obligations under Executive Order

11246, as amended, 3 C.F.R. 160 et seq. (1974).

The complaint charged that the companies had violated

Title VII and Executive Order 11246 by hiring and assign

ing employees on impermissible grounds, and by restricting

ethnic minorities and females to low-paying and undesir

able jobs with scant opportunities for advancement. The

complaint also charged the companies and the union with

formulating collective bargaining contracts which estab

lished seniority systems for promotion, layoff, recall and

transfer so as to deprive minority and female employees

of opportunities for advancement comparable to those

enjoyed by white males.

The filing of the complaint culminated more than six

months of intensive, hard-fought negotiations between, on

one side, the EEOC and Departments of Justice and Labor,

and on the other the companies and the union. Simultane

ously with the filing of the complaint, the parties announced

to the court that a tentative nationwide settlement had been

reached. The parties multilateraliy reduced their agree

ment to the form of two extensive written consent decrees.

Describing the decrees as “a thoughtful and earnest attempt

to respond to—and to reconcile competition between—

charges of employment discrimination made on behalf of

black, female, and Spanish surnamed workers and appli

cants,” 2 District Judge Pointer signed and entered the

documents later that same day.3

2 See United States v. Allegheny-Lndlura Indus., Inc., N.D.Ala.

1974, 63 F.R.D. 1, 3.

8 The two consent decrees are reprinted in BNA FBP Manual

431:125—152 (1974). The correct entry date, as reflected in the

record, is April 12, 1974, rather than April 15.

O pin ion of the C o u rt of A p p e a ls , August 18, 1975

17a

Consent Decree I is aimed at the practices of the union

as well as those of the steel companies. It permanently

enjoins the defendants from “discriminating* in any aspect

of employment on the basis of race, color, sex or national

origin and from failing or refusing to fully implement”

the substantive relief set forth therein. The items covered

by Consent Decree I are mainly matters historically encom

passed by collective bargaining. The substantive relief

falls into three basic categories: (1) immediate implemen

tation of broad plantwide seniority, along with transfer

and testing reforms, and adoption of ongoing mechanisms

for further reforms of seniority, departmental, and line of

progression (LOP) structures, all of which are designed

to correct the continuing effects of past discriminatory

assignments; (2) establishment of goals and timetables for

fuller utilization of females and minorities in occupations

and job categories from which they were discriminatorily

excluded in the past; and (3) a back pay fund of $30,-

940,000, to be paid to minority and female employees

injured by the unlawful practices alleged in the complaint.4

Consent Decree II and its accompanying Agreement deal

with aspects of employment which are mainly company-

controlled and thus not subject to collective bargaining.

The companies again are broadly enjoined from any form

of unlawful employment discrimination. Also, Consent De

4 Paragraph 18(c) of Consent Decree I defines as the affected

classes of emplojrees eligible to receive back pay: (1) minority

(black and Spanish-American surnamed) employees in Production

and Maintenance units who were employed prior to January 1,

1968; (2) all females in Production and Maintenance units as of

the date of decree entry; and (3) those former employees who

retired on pension within the two years preceding entry of the

decrees, who, if they were still employed, would be within group

(1) or group (2). Provision is also made for payment of baek

pay to surviving spouses of otherwise eligible deceased employees.

O pin ion o f the C o u rt o f A p p e a ls , A u g u s t 18, 1975

18a

cree II requires the companies to initiate affirmative action

programs in hiring, initial assignments, promotions, man

agement training, and recruitment of minorities and fe

males.

The decrees must be made to function in varying and

peculiar situations in accordance with the parties’ ambi

tious objectives. Furthermore, the parties contemplated

that unforeseen interpretive issues will inevitably arise

and require resolution. With these considerations in mind,

the decrees provide for the establishment of implementa

tion and enforcement procedures through a system of Im

plementation Committees. These committees are estab

lished at each major plant to which the decrees are made

applicable. Each committee includes at least two union

representatives, one of whom is a member of the largest

minority group in the plant,5 and an equal number of com

pany members. The government is entitled to designate a

representative to meet with any Implementation Commit

tee. The Implementation Committees are charged with as

suring compliance with Consent Decree I, including changes

in local seniority rules and LOPs, as well as the establish

ment of goals and timetables for affirmative action under

paragraph 10. In addition, it is the Implementation Com

mittees’ responsibility to furnish employees with informa

tion about their rights under the settlement.

The Audit and Review Committee, established under

paragraph 13 of Consent Decree I, is the hub mechanism

in the decrees’ system of continuing review, enforcement,

and compliance. It is composed on an industry-wide basis

5 Paragraph 12 of Consent Decree I provides for a second min

ority member at plants in which at least ten percent of the em

ployees comprise a second minority group, unless one of the union

representatives is already from that minority group.

O pin ion o f the C o u rt o f A p p e a ls , A u g u s t 18, 1975

19a

of five management members, five union members, and one

government member. It meets regularly to oversee com

pliance with the decrees and to resolve disputes which come

before it, including any questions that the Implementation

Committees have been unable to resolve. Matters which

the Audit and Eeview Committee cannot resolve unan

imously may be brought before the district court. Fur

thermore, all parties to the decrees have stipulated on the

record that paragraph 20 of Consent Decree I, which vests

the district court with continuing jurisdiction for at least

five years, permits the court to review fully and, if nec

essary, correct any action taken pursuant to the decrees,

irrespective of whether a party requests such review. Be

ginning no later than December 31, 1975, the Audit and

Eeview Committee wall review the entire experience under

Consent Decree I. The committee may then propose

remedial steps at any plant in order to overcome deficien

cies in either the decree or its results. If the government

representative remains dissatisfied with a committee pro

posal, he may take the matter to the district court. Finally,

the Audit and Eeview Committee is responsible at least

annually for reviews of the various Implementation Com

mittees’ performance in establishing and fulfilling affirma

tive action goals in job assignment, hiring, promotion and

seniority, and minority-female recruitment.

As the district court correctly determined, neither de

cree purports “to bind any individual employee or to pre

vent the institution or maintenance of private litigation.” 6

At the time of the decrees’ entry, hundreds of employment

discrimination charges were pending against the defen

dants before the EEOC and federal district courts scattered

Opinion o f the C o u rt o f A p p e a ls , A u g u s t 18, 1975

63 F.R.D. at 4.

20a

throughout the country. Between twenty and sixty thou

sand minority and female individuals then stood beneath

the overlapping umbrellas of these charges as members of

putative aggrieved classes in actions seeking systemic in

junctive relief and back pay. Thousands still do, and the

problems of administrative and judicial management are

truly awesome.7 The consent decrees establish a formula

7 A revealing illustration is the purported class action involving

United States Steel’s Fairfield Works in Alabama, now pending

on appeal before this court, No. 73—3907, Ford, et al. v. United

States Steel Corp., et al., partially reported below at 371 F.Supp.

1045 (N.D.Ala. 1973). Approximately 12,000 people are employed

at Fairfield Works, around 3,100 of whom are black. Between six

and eight private class actions were consolidated for trial. Back

pay was awarded to some members of three classes, but denied as

to the other classes. A total of sixty-one people, or thirteen percent

of the members of the certified private classes, received back pay

awards. The other eighty-seven percent, or 403 blacks, were denied

back pay. Nonetheless, in anticipation of the appeal, the district

court on May 2, 1973 amended the class certification order to re

define the plaintiff class as: (1) all blacks, except those already

members of a private class whose rights had been adjudicated, who

had been employed at Fairfield Works at any time prior to Jan

uary 1, 1973; and (2) all blacks who had unsuccessfully sought

employment at Fairfield Works prior to January 1, 1973. Although

we have no reliable estimate on the combined size of the resulting

class, subclass (1) alone is sufficiently large to have encouraged

the defendants to enter into consent decrees with the government,

in which $30.9 million is promised in back pay, “several million

dollars” of which represents United States Steel’s allotment, prin

cipally for blacks, but also for female and Spanish-surnamed work

ers at Fairfield Works. Brief for Appellee United States Steel

Corp., at 7, No. 73—3907, Ford, et al. v. United States Steel Corp.,

et al.

The Fairfield Works case also involved pattern or practice charges

brought by the United States, resulting in an appeal by the govern

ment from denial of certain injunctive relief and denial of back

pay to black employees who were not represented in the private

class actions. Since the government is now admittedly satisfied

with the rate retention and back pay provisions of subsequently-

negotiated Consent Decree I, paragraphs 8 and 18 thereof respec

tively, it has withdrawn its appeal in Ford pending our decision

Opinion of the Court of Appeals, August 18, 1975

21a

for expeditious and coordinated resolution of the multitude

of pending charges. With respect to pending cases in

which district courts have already entered remedial de

crees, the government, companies, and union have agreed

to petition those courts for amendments to conform their

relief to that contained in the consent decrees. The same

action is being taken with respect to orders of the Secre

tary of Labor, rendered pursuant to Executive Order

11246, which were issued prior to entry of the decrees. In

regard to other pending litigation, the parties to the con

sent decrees have agreed that release forms and notices to

employees pursuant to subparagraphs 18(g) and (h) of

Consent Decree I shall be forwarded to the courts trying

the private actions, as well as to Judge Pointer for ap

proval prior to distribution to all other affected employees.

The parties have agreed on the record that they will ob

serve any order or instruction issued by any of these

courts. Audit and Review7 Committee Directive No. 1, 5,

May 31, 1974.

Under introductory paragraph C of each decree, the

government has stipulated that in future cases involving

private claims for relief, other than hack pay, wdiich would

be inconsistent with the systemic relief provided by the

decrees, the government will suggest to the forum court

that the relief sought is unwarranted in the separate pro

O pinion o f the C o u rt o f A p p e a ls , A u g u s t 18, 1975

as to the validity of the consent decrees sub judice. Stipulation of