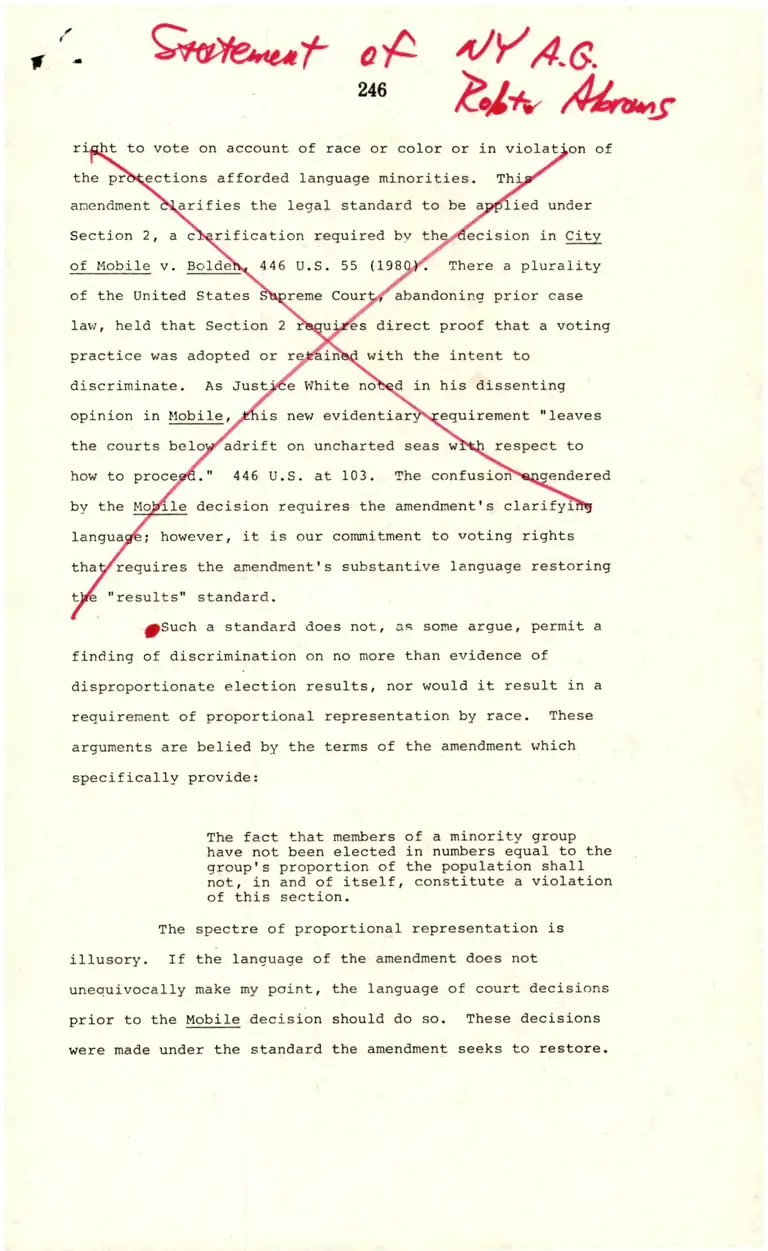

Legal Research on Statement of Robert Abrams

Unannotated Secondary Research

January 1, 1982

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Legal Research on Statement of Robert Abrams, 1982. e75f5908-e192-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/cac72c09-2f83-4392-b671-1060d2bea2c1/legal-research-on-statement-of-robert-abrams. Accessed March 14, 2026.

Copied!

I- W7” 20p ”V46

£911? an";

Section 2, a c ecision in City

of Mobile v. Bolde 446 U.S. 55 (198 There a plurality

of the United States.

law, held that Section 2 es direct proof that a voting

practice was adopted or r with the intent to

discriminate. As Just‘ e White no d in his dissenting

opinion in Mobile, is new evidentiar equirement "leaves

the courts belo adrift on uncharted seas w respect to

446 U.S. at 103. The confusion endered

"results" standard.

l'Such a standard does not, as some argue, permit a

finding of discrimination on no more than evidence of

disproportionate election results, nor would it result in a

requirement of proportional representation by race. These

arguments are belied by the terms of the amendment which

specifically provide:

The fact that members of a minority group

have not been elected in numbers equal to the

group's proportion of the population shall

not, in and of itself, constitute a violation

of this section.

The spectre of proportional representation is

illusory. If the language of the amendment does not

unequivocally make my point, the language of court decisions

prior to the Mobile decision should do so. These decisions

were made under the standard the amendment seeks to restore.

247

In these decisions, the Supreme Court, as well as lower

federal courts, never imposed a requirement of proportional

representation, nor did those courts find that the mere lack

of minority officeholders was sufficient to prove

discrimination. Indeed, such concepts were specifically

rejected..For example, in White v. Register, the Supreme

Court held:

To sustain such claims it is not enough that

the racial group allegedly discriminated

against has not had legislative seats in

proportion to its voting potential. The

plaintiffs' burden is to produce evidence to

support findings that the political processes

leading to nomination and election were not

equally open to participation by the group in

question -—- that its members had less

opportunity than did other residents in the

district to participate in the political

processes and to elect legislators of their

choice. 412 U.S. at 765 - 66.

The pre—Mobile cases focused on whether minorities

had less opportunity than others to participate in the

electoral process and not simply on the results of

elections. In so doing, they considered the totality of

circumstances surrounding the challenged procedures. Again,

referring to flhitg v. Register, the Supreme Court applied

the "results" standard and struck down at—large voting

procedures in two Texas counties, based on the trial court's

"intensely local appraisal" of a wide range of facts showing

that Mexican-Americans were “effectively removed from the

political processes ...." 412 U.S. at 769.

By contrast, the intent test, as interpreted by

the Mobile Court, requires courts to inquire into the

elusive area of motive and often requires plaintiffs to

prove the thoughts and intentions of long-dead officials.

It is an impossible burden in almost any situation, and it

248

is assuredly one that cannot appropriately be imposed in the

critical area of voting rights. I say this with the full

knowledge that I am advocating rejection of a standard which

would virtually insulate from attack voting practices which

as the Attorney General of the State of New York I may be

called upon to defend. However, we are not here evaluating

trial strategies, but rather the legal standards necessary

to ensure equality of access to the right to vote. The

amended Section 2 is vital to that effort.

THE PRECLEARANCE REQUIREMENT

Although the State of New York, like every state

in this Nation, is subject to the prohibitions of Section 2

of the Act, only 22 States, including three New York

counties, are subject to the preclearance requirement of

Section 5 of the Act. The counties of Kings, New York and

Bronx first came within the purview of the Act in March,

1971. It was then that the United States Attorney General

determined that the literacy requirement imposed by New York

law was a "test or device" within the meaning of the Voting

Rights Act, and the Director of the Census Bureau determined

that less than 50% of the persons of voting age residing in

each of the three counties had voted in the preceding

presidential election. Thereafter, as allowed by the Act,

the three counties attempted to be exempted by the federal

court from the preclearance requirement. They tried without

success to demonstrate that New York's literacy test had

neither the purpose nor effect of abridging any citizen's

right to vote on account of race or color. As a result, New

York has been required to submit to the Department of

Justice all the voting laws and procedures enacted since

November 1, 1968 which affect any of the three counties.