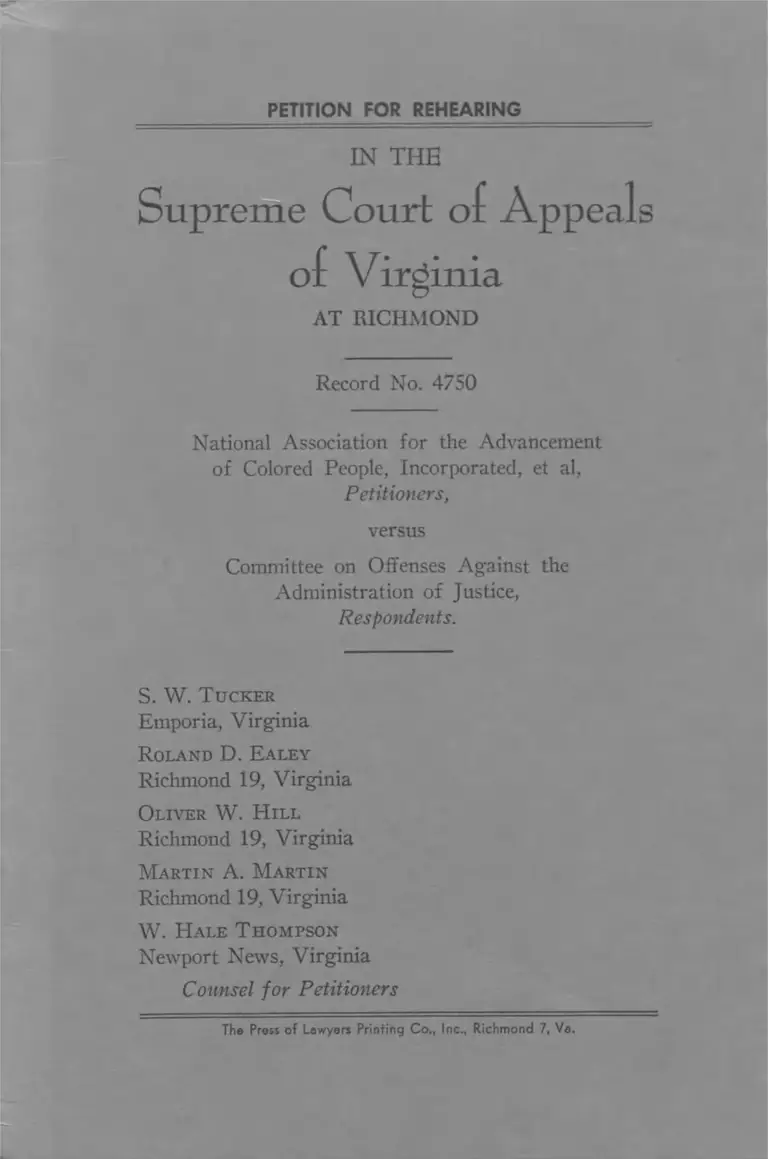

NAACP v. Committee on Offenses Against the Administration of Justice Petition for Rehearing

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1958

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. NAACP v. Committee on Offenses Against the Administration of Justice Petition for Rehearing, 1958. 7dd5222e-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/cb8348ad-467c-46fd-90bf-04828a09941e/naacp-v-committee-on-offenses-against-the-administration-of-justice-petition-for-rehearing. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

PETITION FOR REHEARING

IN THE

Suprem e C ourt of A ppeals

of V ir ginia

AT RICHMOND

Record No. 4750

National Association for the Advancement

of Colored People, Incorporated, et al,

Petitioners,

versus

Committee on Offenses Against the

Administration of Justice,

Respondents.

S. W. T ucker

Emporia, Virginia

Roland D. E aley

Richmond 19, Virginia

Oliver W. H ill

Richmond 19, Virginia

Martin A. Martin

Richmond 19, Virginia

W. H ale T hompson

Newport News, Virginia

Counsel for Petitioners

The Press of Lawyers Printing Co., Inc., Richmond 7, Va.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Petition For Rehearing................................................ 1

Argument ....................................................................... 4

Conclusion ........................................................ 1........... 15

TABLE OF CASES

American Communications Association v. Douds, 339

U.S. 382, 70 S. Ct. 674, 94 L ed 925 ........................ 8

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U. S. 249 .............................. 12

Brewer v. Hoxie School District, 8 Cir. 238 F. 2d 91 .. 12

Herndon v. Lowry (1937) 301 U. S. 242, 81 L ed

1066, 57 S. Ct. 732 ................................................ — 9

National Association for the Advancement of Colored

People, et al, v. Kenneth C. Patty, Attorney-Gen

eral, et al (Civ. Nos. 2435 and 2436, E. D. Va.,

decided January 21, 1958)............... 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 11, 14

Sweezy v. New Hampshire, 354 U. S. 234, 1 L ed 2d

1311........................................................................... 5,11

Thomas v. Collins (1945) 323 U. S. 516, 89 L ed 430,

65 S. Ct. 315............................................................... 14

United States v. Harris (1954) 347 U. S. 612, 98 L

ed 989, 74 S. Ct. 808 .................................................. 10

Watkins v. United States, 354 U. S. 178, 1 L ed 2d

1273 ....................... 11

West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette

(1942) 319 U. S. 624, 63 S. Ct. 1178, 147 ALR

674, 87 L ed 1628............................................. -....... 9

Page

OTHER REFERENCES

Rule 5:1, Section 4, Rules of Supreme Court of Ap

peals of V irginia........................................................ 6

Rule 28, Canons of Professional E th ics.................... 7

Chapter 35, Acts of General Assembly of Virginia,

Extra Session, 1956 .....................-.......................... 3

IN THE

Suprem e C ourt of A ppeals

of Virc dnia

AT RICHMOND

Record No. 4750

National Association for the Advancement

of Colored People, Incorporated, et al,

Petitioners,

versus

Committee on Offenses Against the

Administration of Justice,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR REHEARING

To the Honorable Justices of the Supreme Court of

Appeals of Virginia:

This petition for rehearing is filed by and on behalf

of the National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People, a corporation, the Virginia State Con

ference of NAACP Branches, and W. Lester Banks, as

Executive Secretary of said Conference, and also by

said W. Lester Banks in his own right as a member of

said Association residing in Virginia and on behalf of

other persons similarly situated. Said petitioners pray a

rehearing of the case styled National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People, et al, vs. Committee on

Offenses Against the Administration of Justice, Record

No. 4750, decided January 20, 1958, in which this Court

held that the Hustings Court of the City of Richmond

had properly caused the issuance of subpoenas duces

tecum to compel certain papers and records of the peti

tioning organization to be produced before the respond

ent committee.

In so deciding this case, the Court stated: “. . . the

real issue is whether the witness should be compelled to

disclose the names and addresses of the members of the

NAACP, and its voluntary workers and associates, in

Virginia.” But having properly defined the issue, the

Court then proceeded expressly to decide broad consti

tutional issues, which by the very nature of the record

had not been fully developed upon the original hearing;

and, by necessary inference, to decide the constitution

ality of other acts of the General Assembly, Extra Ses

sion, 1956, all of which is in conflict with a decision of

the United States District Court for the Eastern District

of Virginia, rendered on January 21, 1958. in National

Association for the Advancement of Colored People, et

al, vs. Kenneth C. Patty, Attorney-General, et al (Civil

Actions Nos. 2435 and 2436) (hereinafter referred to

3

as N AAC P vs. Attorney General), a case involving the

basic issues here determined.

The case of N AAC P vs. Attorney General involved

the constitutionality of the package of laws commonly

referred to as “Anti-NAACP” statutes, namely Chap

ters 31, 32, 33, 35 and 36, Acts of the General Assem

bly, Extra Session, 1956. In this case and a companion

case on behalf of the NAACP Legal Defense and Edu

cational Fund, the power of the State to compel the dis

closure of the names and addresses of its members, con

tributors, voluntary workers and associates through reg

istration laws (Chapters 31 and 32) was challenged.

This case also challenged the validity of Chapters 33,

35 and 36, Acts of the General Assembly, Extra Session,

1956, through which the State sought to make unlawful

the activity of the Association in sponsoring litigation

attacking racial segregation. The District Court held

Chapters 31, 32 and 35 unconstitutional and held the

case open pending an interpretation of Chapters 33 and

36 by the State courts.

In view of the eminence of the respective Courts ren

dering conflicting decisions, the grave public issues in

volved, and the fact that in the case of N AAC P vs.

Attorney General, supra, the Court had the benefit of a

full record which this Court did not, we ask a rehearing

of the instant case on the following ground:

This Court has passed on a question which was neither

presented by an assignment of error nor raised else

where in the record and, in so doing, has abridged rights

secured by the First Amendment and protected against

4

State action by the due process clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Federal Constitution.

ARGUMENT

A

Upon a record which was not specially developed for

such purpose, the Court has decided Federal Constitu

tional questions which were not in issue here.

The Court broadened the scope of the questions pre

sented and then extended its negation of the asserted

constitutional rights to encompass a denial of rights pro

tected by the First Amendment. We quote from the

opinion:

“. . . (3) Does the disclosure of the information

sought by the subpoenas violate any constitutional

rights of the appellants? (Emphasis supplied.)

* * *

“. . . Nor do we agree with the suggestion in the

appellants’ brief that the required disclosure of the

names of their members and associates ‘would be

necessarily coercive’ and therefore a restraint on

their freedom of speech or right of assembly guar

anteed by the First Amendment. No limitation by

license or otherwise on the activities of the appel

lants is here involved. This is an inquiry into such

activities and the identity of those who are involved

therein, to ascertain whether they are engaged in

unlawful practices. Clearly, this is within the State’s

police power.”

5

The motion to quash the subpoena from the Hustings

Court of the City of Richmond does not, in terms, men

tion the Constitution of the United States. The Assign

ments of Error invoked the due process clause of the Four

teenth Amendment only to the extent that said clause and

its counterpart in Section 11 of the Constitution of Vir

ginia may have had a bearing upon the procedure fol

lowed in the Court below. The “due process” challenges

were to the entry of the lower court’s initial judgment

order upon an ex parte application (second assignment)

and to the action of the Court below in so far as it (en

tirely) relieved the Committee of the onus probandi

(third assignment). Except to state The Errors Assigned

in their original language, the appellants in their opening

brief avoided all mention of the Fourteenth Amendment

to the Federal Constitution. The citation of Swcezy vs.

New Hampshire, 354 U. S. 234, 1 L ed 2d 1311, as an

illustration of a failure to show that the information

sought was required by the legislative directive, could

not be taken as an invocation of federal law.

Only questions of state procedural and substantive law

were formally presented to the state courts. Prior to the

commencement of any proceeding in the state court,

questions of a substantive federal law, and particularly

questions involving rights secured by the First Amend

ment as incorporated into the Fourteenth, had been ten

dered to the United States District Court for the Eastern

District of Virginia in the cases of N A AC P vs. Attor

ney General, supra. A record appropriate for the disposi

tion of such questions was developed in that Court and

a decision of those issues, contrary to the decision of

this Court, was rendered on January 21, 1958. Even be

6

fore the motion to quash subpoenas was filed in the court

below, these issues of federal law had also been made the

subject of controversy between the parties here in the

case of National Association for the Advancemeiit of

Colored People, etc., et al, vs. Ames, et al, (Civil Action

No. 2480) still pending in said United States District

Court, a copy of the proceedings in which were filed here

by the appellee during the oral argument.

Petitioners could not anticipate that this issue, orig

inally addressed to the District Court and yet pending

before it, would be decided in the instant proceeding. Nor

could they anticipate a ruling on that issue in this Court.

Rule 5:1, Section 4, of the Rules of this Court is explicit

that only errors duly assigned will be noticed by this

Court. The effect of the decision is clear. The compelled

disclosure of the names and addresses of the Associa

tion’s members, voluntary workers and associates “con

stitutes a restriction upon the right of free speech which,

as we have seen, the Association is entitled to exercise.

*** (R)egistration of names of persons who resist the

popular will would lead not only to expressions of ill

will and hostility but to the loss of members by the plain

tiff’s Association.” N A AC P vs. Attorney General, supra.

The decision in the instant case necessarily deprives peti

tioners, and the many thousands of persons they repre

sent, of vital constitutional rights without opportunity

to be heard.

In this same connection this Court cited Chapter 35.

Acts of General Assembly, 1956, as the basis for the re

quirement that the Association disclose the names and

addresses of its members, voluntary workers and asso

7

ciates and buttressed it with a citation of Rule 28 of the

Canons of Professional Ethics. Obviously, this pre

supposes that Chapter 35 as applied to these petitioners

is constitutional without affording appellants an oppor

tunity to point out the infirmities of Chapter 35. The

error is all the more apparent when it is considered that

the first Court to which the constitutionality of Chapter

35 was fully and adequately presented declared it uncon

stitutional as applied to the activities of these petitioners.

The decision in N AAC P vs. Attorney General, supra, not

only expressly declared Chapter 35 unconstitutional, but

also clearly pointed out the inapplicability of Rule 28 in

the premises.

It is well established that an invalid statute cannot form

the basis for coercive state action. (N AAC P vs. Attorney

General, supra; Sweezy vs. New Hampshire, supra.)

B

Compulsory disclosure of names of members of peti

tioning organizations would, at the least, impinge upon

First Amendment rights. Such disclosure would be but

a species of “thought inspection.” Disclosure of the names

of members would involuntarily lay bare the individual

opinions of 23,000 citizens residing in the Common

wealth on its most controversial subject of the century.

Thoughts are inviolate. The peaceable association for a

lawful purpose is also inviolate.

In the case of N AAC P vs. Attorney General, supra.

the effort of the Commonwealth of Virginia to require

disclosure of the names of the contributors and members

8

of the petitioning organizations was clearly denounced

as an invasion of First Amendment rights.

The case is not removed from the protection of the

First Amendment by the Court’s observation that “ ( n)o

limitation by license or otherwise on the activities of the

appellants is here involved.” In American Communica

tions Association v. Douds, 339 U. S. 382, 70 S Ct. 674,

94 L ed 925, five justices, for the Court, upheld a Con

gressional requirement that leaders of labor unions which

seek to obtain advantages under labor relations legisla

tion must file affidavits disclaiming membership in Com

munist organizations; and an equally divided Court up

held the requirement of the statute that the union official

state that he does not believe in the Communist doctrine.

Justification for the restraint was rested upon general

information that labor leaders, acting under orders of

the Communist Party, called strikes merely to disrupt

the national economy and upon the legislative judgment

that interstate commerce must be protected from a con

tinuing threat of strikes. However, the Court (and. more

vigorously, the dissenting justice and the justices dis

senting in part and concurring in part) clearly recog

nized the required disclosure as an abridgement of free

dom of speech. To quote language of Chief Justice Vin

son, for the Court:

“. . . (T )he fact that no direct restraint or punish

ment is imposed upon speech or assembly does not

determine the free speech question. Under some cir

cumstances, indirect ‘discouragements’ Undoubtedly

have the same coercive effect upon the exercise of

First Amendment rights as imprisonment, fines, in-

9

junctions or taxes. A requirement that adherents of

particular religious faiths or political parties wear

identifying arm-bands, for example, is obviously of

this nature . . . (339 U. S. at 402)

C

Any subordination of First Amendment rights to the

police power must be clearly justified by the government

in terms of its own self preservation.

“The power of a state to abridge freedom of speech

and of assembly is the exception rather than the

rule . . . . ” Herndon v. Lowry (1937) 301 U. S. 242,

258, 81 L ed 1066, 1075, 575 S Ct. 732.

In the case of West Virginia State Board of Education

v. Barnette (1942) 319 U. S. 624, 639, 63 S Ct. 1178.

147 ALR 674, 87 L ed 1628, the Court said:

“. . . ( I ) t is important to distinguish between the

due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment as

an instrument for transmitting the principles of the

First Amendment and those cases in which it is ap

plied for its own sake. The test of legislation which

collides with the Fourteenth Amendment, because

it also collides with the principles of the First, is

much more definite than the test when only the

Fourteenth is involved. Much of the vagueness of

the due process clause disappears when the specific

prohibitions of the First become its standard. The

right of a State to regulate, for example, a public

utility may well include, so far as the due process

10

test is concerned, power to impose all of the restric

tions which a legislature may have a ‘rational basis’

for adopting. But freedoms of speech and of press,

of assembly, and of worship may not be infringed

on such slender grounds. They are susceptible of

restriction only to prevent grave and immediate

danger to interests which the state may lawfully

protect. . . .”

In United States v. Harris (1954) 347 U. S. 612, 98

L ed 989, 74 S Ct. 808, the justices recognized that Con

gress had impinged upon the area of First Amendment

rights when, by passing the Federal Regulation of Lobby

ing Act, it required identification of those who employed

professional lobbyists. The constitutionality of the

abridgement was upheld; but only because, in the opin

ion of five of the justices, the purpose of the Congress

has been “to maintain the integrity of a basic govern

mental process.” Said the Court:

“Under these circumstances, we believe that Con

gress, at least within the bounds of the Act as we

have construed it, is not constitutionally forbidden

to require the disclosure of lobbying activities. To

do so would be to deny Congress in large measure

the power of self protection. And here Congress has

used that power in a manner restricted to its ap

propriate end.” 347 U. S. at 625.

No attempt at justification for the demand of the

names of members is reflected in the record here; neither

was any valid justification shown in the United States

District Court in the case of N AAC P vs. Attorney Gen-

11

oral, supra, in which this specific issue was made up and

extensively developed.

D

The right of legislative investigation cannot transcend

First Amendment rights. In Watkins v. United States,

354 U. S. 178, 1 L Ed 2d 1273, 1290, the Supreme Court

observed:

“We cannot simply assume, however, that every

congregational investigation is justified by a public

need that over balances any private rights affected.

To do so would be to abdicate the responsibility

placed by the Constitution upon the judiciary to in

sure that the Congress does not unjustifiably en

croach upon an individual’s right to privacy nor

abridge his liberty of speech, press, religion or as

sembly.”

In Sweezy v. Nezv Hampshire, supra, these admoni

tions appear:

“It is particularly important that the exercise of the

power of compulsory process be carefully circum

scribed when the investigative process tends to im

pinge upon such highly sensitive areas as freedom

of speech or press, freedom of political association,

and freedom of communication of ideas . . . ” (1 L

ed 2d at 1322)

* * *

“Merely to summon a witness and compel him

12

against his will, to disclose the nature of his past

expressions and associations is a measure of gov

ernmental interference in these matters. These are

rights which are safeguarded by Bill of Rights and

the Fourteenth Amendment.” (1 L ed 2d at 1324)

E

Rights of the petitioners under the First Amendment

take the color and substance of the rights of their indi

vidual constituents or members.

“. . . (W)e may fairly consider not only the rights

of the plaintiff corporations but also the rights of

the individuals for whom they speak, particularly

the rights of the members of the Association . . . .

The rights that the plaintiffs assert take their color

and substance from the rights of their constituents;

and it is now held that where there is need to protect

fundamental constitutional rights the rule of prac

tice is relaxed, which confines a party to the asser

tion of his own rights as distinguished from the

rights of others. See Barrows vs. Jackson, 346 U. S.

249, 257. This rule was applied in Brezver vs. Hoxie

School District, 8 Cir., 239 F. 2d 91, 104, where the

school board in an Arkansas county brought suit to

restrain certain organizations from obstructing the

board in its efforts to secure the equal protection of

the laws to all persons in the operation of the public

schools in the district. The court said:

“ ‘The school board having the duty to afford the

children the equal protection of the law has the cor

relative right, as has been pointed out, to protection

13

in performance of its function. Its right is thus in

timately identified with the right of the children

themselves. The right does not arise solely from the

interest of the parties concerned, but from the neces

sity of the government itself. *** Though, generally

speaking, the right to equal protection is a i>ersonal

right of individuals, this is ‘only a rule of practice’,

*** which will not be followed where the identity of

interest between the party asserting the right and

the party in whose favor the right directly exists is

sufficiently close’ ” N A A C P vs. Attorney General,

supra. See also so much of that opinion in which

the Court discusses “Civil Rights of Corporations” as

a phase of the Court’s disposition of “Defendant’s

Motion to Dismiss.”

F

The State’s procedural concept of due process is in

adequate here. One of the 'arguments of the appellants

was that due process required the Court to hear both

sides before rendering judgment and another argument

was that the burden of proof should have been imposed

upon the appellee to show the materiality of the informa

tion sought to any legitimate purpose of the committee.

As far as the procedural law of this Commonwealth goes,

these questions were resolved against the appellants. But:

if the opinion of this Court is to be read as holding that

such procedure squares with the due process clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment even as it protects First

Amendment rights, then such opinion clashes with this

Federal requirement:

“ (A)ny attempt to restrict those liberties must be

14

justified by clear public interest, threatened not

doubtfully or remotely but by clear and present dan

ger. The rational connection between the remedy

provided and the evil to be curbed, which in other

contexts might support legislation against attack on

due process grounds, will not suffice. These rights

rest on firmer foundation. Accordingly, whatever

occasion would restrain orderly discussion and per

suasion, at appropriate time and place, must have

clear support in public danger, actual or impend

ing. Only the gravest abuses, endangering para

mount interests, give occasion for permissible limi

tation. It is therefore in our tradition to allow the

widest room for discussion, the narrowest range for

its restriction, particularly when this right is exer

cised in conjunction with peaceable assembly. It was

not by accident or coincidence that the rights to free

dom of speech and press were coupled in a single

guaranty with the rights of the people peaceably to

assembly and to petition for redress of grievances.

All these, though not identical, are inseparable.

* * *

“. . . There is some modicum of freedom of thought,

speech and assembly which all citizens of the re

public may exercise throughout its length and

breadth, which no State, nor all together, nor the

Nation itself, can prohibit, restrain or impede.”

Thomas v. Collins (1945) 323 U. S. 516, 530, 543,

89 L ed 430, 65 S Ct. 315.

In dealing with the precise questions involved in this

case, the Court, in N A AC P vs. Attorney General, supra,

stated:

15

“No doubt, the State of Virginia has the right

reasonably to regulate the practice of law. but,

where that regulation prohibits otherwise lawful

activities without showing any rational connection

between the prohibition and some permissible end of

legislative accomplishment, the regulation fails to

satisfy the requirements of due process of law. Here,

under the guise of regulating unauthorized law prac

tice, the General Assembly has forbidden plaintiffs

to continue their legal operations.”

CONCLUSION

For the reasons hereinabove stated, petitioners pray

that they be granted a rehearing in this case and that

upon a rehearing the decision of this Court upon the

constitutional questions be reversed and that the affirm

ance by his Court of the judgment rendered in the court

below be reversed, or at least be so restricted as to protect

petitioners’ constitutional rights.

Respectfully submitted,

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR TH E

ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEO

PLE, INCORPORATED; V I R G I N I A

STATE CONFERENCE OF NAACP

BRANCHES; W. LESTER BANKS, Ex

ecutive Secretary of said Conference; and

W. LESTER BANKS in his own right as

a member of said Association residing in

Virginia and on behalf of other persons sim

ilarly situated.

By S. W. T ucker

O f Counsel

16

S. W. T ucker

Emporia, Virginia

Roland D. E aley

.420 North First Street

Richmond 19, Virginia

Oliver W. H ill

118 East Leigh Street

Richmond 19, Virginia

Martin A. Martin

118 East Leigh Street

Richmond 19, Virginia

W. H ale T hompson

611 - 25th Street

Newport News, Virginia

Counsel for Petitioners

CERTIFICATE

I certify that three copies of this petition will be de

livered or mailed to opposing counsel.

Oliver W. H ill

O f Counsel for Petitioners