Letter to Ms. McGuan from Reynolds re Additional Information concerning H.B. No. 2, Chap. 1

Public Court Documents

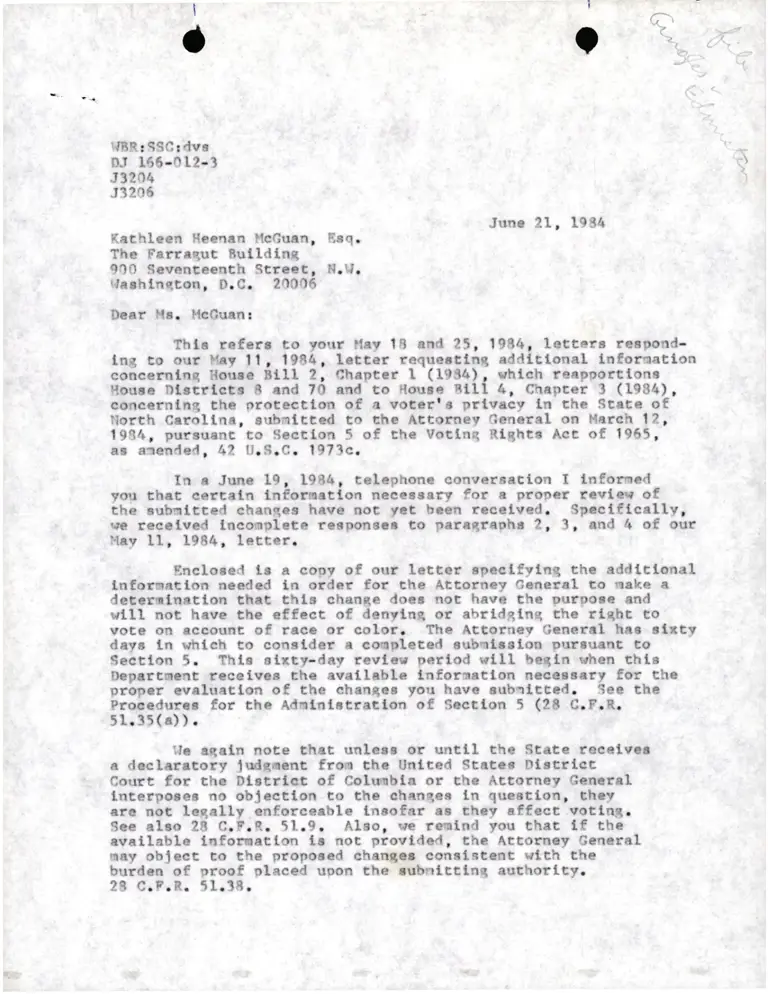

June 21, 1984

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Hardbacks, Briefs, and Trial Transcript. Letter to Ms. McGuan from Reynolds re Additional Information concerning H.B. No. 2, Chap. 1, 1984. 2cf50a72-d592-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/cbb44934-a31f-4a45-951c-722c3c2081e7/letter-to-ms-mcguan-from-reynolds-re-additional-information-concerning-hb-no-2-chap-1. Accessed February 03, 2026.

Copied!

C-,(

I'IBRtSSCldvr

DJ 156-0t2-3

J3?04

J3206

June 21, 1984

Kathleen Heenan l'lcGuan, Esq.

The Farrnq,ut Butldlng

900 Seventeenth Streec, N.U.

ttreahlnqtonr D.C. 20A06

Deer Ha. HcGuanr

Thle referr to yotrr ltay lB and 25, 1994, lettera respond-

lnB to our Hay ll, 1984, letter requeatlnq, addlt,tonal lnforraatton

coneerntnq Houae 8111 2, Chapter 1 (191t4), whtch recDoortlone

Houte Dtetrtctg I and 70 and to Houte 8111 4, Chapter 3 (1984),

concernlnq, the orotectl.on of a votcrt a prtvacy ln the State of

l'Iorth Caroltna, arrbinttted to thc AEtornev Genoral on Harch t2,

193/r, purguant to Sectlon 5 of the votlnq RLghta Act of t955,

ae anended, 42 l,.S.C. 1973c.

In e June 19, 1984, telephone converoecton I tnforncd

you that eertatn lnforoatton neeersery fot a proper rcvtetr of

the aubnltted chanl,as have not yct bcen receLved. Speclflceltv,

'rre recctved tncornplete respon8ai to paraqraohc ?- ) 3, and 4 of our

l{av 11, 1984, letter.

Eneloee,l Lr a copy of our letter spectfylng thc addtclonal

tnforrnatl.on needed tn order for the Attorney Ceneral to nake a

deterntnatton that thts chanx,e doer not have the purooae and

trtll not have the effect of denytng, or ahrldgtnq Ehe rLght to

vote on accounE of race or color. The Attornev Gcnerel hae ttxEv

days tn whtch to constder a conpleted eubmleslon purruanc to

Sectton 5. Thls atxty-day revlcv perlod w1,11 beqtn when thla

Deplrto€nt rccelvcs Ehe avatlable lnforaetton neeesstry for the

proper eveltratLon of the chanq,ee you hsve aubttttad. See thc

Procedurec for the Adntnlrtretlon of Sectl.on 5 (28 C.F.R.

51.35(a)).

Itrc aqaln note that unlega or untll the SEate racctvcc

a declerrtory ludqroent from thc Untted SEatce DlttrlcE

Court for ths Dlatrlqt of Colutbla or Ehe Attornov Gencral

lnterpoeea no obJectlon to tho sfiano,€a ln queetton, chcy

aro not leqally enforceable tnsofar ee thev affect vottng.

See alao 28 C.F.R.51.9. Alsor'd€ reralnd you that lf the

avallable tnforoatton 1r not rrrovlded, the Attorncy General

rnay obfeet Eo the nropoeed ehangcr conststent wlch the

burden of proof rrlaced uoon the rubnlttlnq authorlty.

28 C.F.R. 51.38.

I

a

t

t

-2-'

If you hevr.ln, qu.rctont oonc.mte; thr rrrcEcrt

dl,rcurmd ta thtr lettrr or ll t Gln rld you ln my rrt co

obtrln Bhc rddttlolrrl tnforaation rr hrvo icquertcd, trll

trrr to ctll lr (202-724-6718). Rrtrr to FlIr llot. Jt20e

rnd Jt206 tn rry r..PoQ.. to Chtr lrttrr ro cbet ,our

corr.rpondeocr rlll br chrnncled proplrly.

SlnorrolT,

Tr. tredford loynoldr

ArrleCrnt ACtosElT Graorel

Clvtl Rt;htr Dlvhtoa

tyr

Orrrld S. Joner

ChLrf , Votl,ng, Scctton

ccr Onltrd St.G.t Dlrtrtct Court

Er.t.rn Dktrtct of iorth Cerollnr

end ell eounml of rccord