Order Amending Opinion; Amended Opinion

Public Court Documents

May 1, 1987 - July 10, 1987

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Chisom Hardbacks. Order Amending Opinion; Amended Opinion, 1987. fdfba731-f211-ef11-9f8a-6045bddc4804. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/cbb6aadc-6466-4fe7-9e9b-94cc43e5b906/order-amending-opinion-amended-opinion. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

• •

mcO ..,

,

t.-

UNIIED STATES DISTRICR4tpall

re I EASTERN DISTRICT OF Loily."01A in V

c y *fOT

' -

CLERIC

RONALD CHISOM, ET AL CIVIL ACTION

VERSUS NO. 86-4075

EDWIN EDWARDS, ET AL SECTION "A"

§§§§§§§§§§§§

ORDER AMENDING OPINION

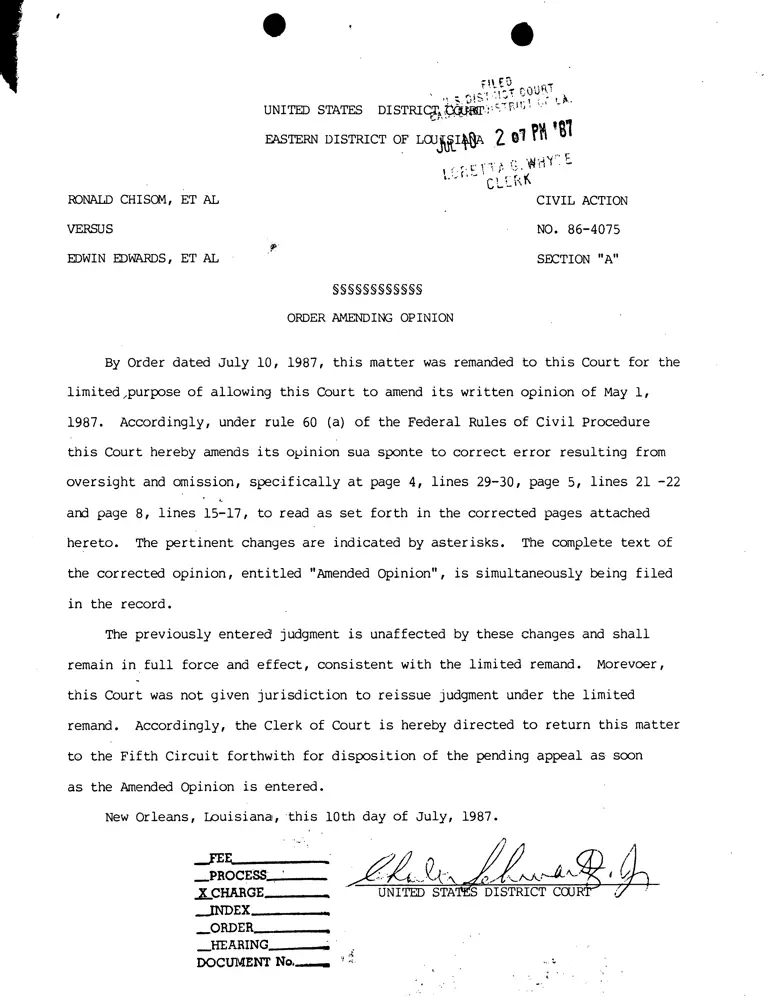

By Order dated July 10, 1987, this matter was remanded to this Court for the

limited,purpose of allowing this Court to amend its written opinion of May 1,

1987. Accordingly, under rule 60 (a) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

this Court hereby amends its opinion sua sponte to correct error resulting from

oversight and omission, specifically at page 4, lines 29-30, page 5, lines 21 -22

and page 8, lines 15-17, to read as set forth in the corrected pages attached

hereto. The pertinent changes are indicated by asterisks. The complete text of

the corrected opinion, entitled "Amended Opinion", is simultaneously being filed

in the record.

The previously entered judgment is unaffected by these changes and shall

remain in full force and effect, consistent with the limited remand. Morevoer,

this Court was not given jurisdiction to reissue judgment under the limited

remand. Accordingly, the Clerk of Court is hereby directed to return this matter

to the Fifth Circuit forthwith for disposition of the pending appeal as soon

as the Amended Opinion is entered.

New Orleans, Louisiana, •this 10th day of July, 1987.

--FEE

PROCESS '

_X_CHARGE

ORDER

HEARING

DOCUMENT

S DISTRICT COUR

S.Ct. 375, 83 L.Ed.2d 311. (1984) 2/ Section 2, as amended, 96 Stat. 134, now

reads:

(a) No voting qualification or prerequisite to voting or

standard, practice, or procedure shall be imposed or applied

by any State or political subdivision in a manner which

results in a denial or abridgement of the rights of any

citizen of the United States to vote on account of race or

color, or in contravention of the guarantees set forth in

section 1973b(f)(2), as provided in subsection (b) of this

section.

(b) A violation of subsection (a) is established if, based

on the totality of the circumstances, it is shown that the

political processes leading to nomination for election in the

State or political subdivision are not equally open to par-

ticipation by members of a class of citizens protected by

subsection (a) of this section in that its members have less

opportunity than other members of the electorate to partici-

pate in the political process and to elect representatives

of their choice. The extent to which members of a protected

class have been elected to office in the State or political

subdivision is one circumstance which may be considered:

Provided, that nothing in this section establishes a right

to have members of a protective class elected in numbers

equal to their proportion in the population.

42 U.S.C. § 1973 (emphasis added).

Prior to the 1982 amendments to section 2, a three-judge court composed of

• Judges Ainsworth, West and Gordon, headed by Judge West, addressed a voting rights

• claim arising out of the same claims of discrimination as in this case, albeit not

• in a section 2 context. Wells v. Edwards, 347 F. Supp. 453 (M.D. La. 1972), aff'd,

409 U.S. 1095, 93 S.Ct. 904, 34 L.Ed.2d 679 (1973). In Wells, a registered black

voter residing in Jefferson Parish, brought suit seeking a reapportionment of

the judicial districts from which the seven judges of the Supreme Court of Louisiana

are elected. Ms. Wells sought an injunction enjoining the state from holding the

scheduled Supreme Court Justice elections and an order compelling the Louisiana

Legislature to enact an apportionment plan in accordance with the "one man, one

2/ See S.Rep. 97-417, 97 Cong.2d Sess (1982) pp. 15-43 for a complete discus-

sion of Congress' intent to overturn the section 2 "purposeful discrimination"

requirement imposed by Mobile v. Bolden.

-4-

vote" principle and to reschedule the pending election. On cross motions for

summary judgment, the three-judge court stated, "We hold that the concept of

one-man, one vote apportionment does not apply to the judicial branch of govern-

ment." 342 F. Supp. at 454. The Wells court took notice of Hadley v. Junior

College District, 397 U.S. 50, 90 S.Ct. 791, 25 L.Ed.2d 45 (1970), in which the

Supreme Court held, "Whenever a state or local government decides to select

persons by popular election to perform governmental functions, the equal protec-

tion clause of the fourteenth amendment requires that each qualified voter must

be given an equal opportunity to participate in that election....", 90 S.Ct.

791, 795 (emphasis added), but distinguished its holding by outlining the special

functions of judges.

The Wells court noted many courts' past delineations between elected officials

who performed legislative or executive functions and judges who apply, but not

create, law 3/ and concluded:

'Judges do not represent people, they serve people.'

Thus, the rationale behind the one-man, one-vote

principle, which evolved out of efforts to preserve a

truly representative form of government, is simply not

relevant to the makeup of the judiciary.

347 F. Supp. at 455.

The Wells opinion interpreted the "one man one vote" principle prior to the

1982 amendments to section 2, which added the phrase "[T]o elect representatives

3/ See, e.g., Stokes v. Fortson, 234 F. Supp. 575 (N.D. Ga. 1964) ("Manifestly,

judges and prosecutors are not representative in the same sense as they are

legislators or the executive. Their function is to administer the law, not to

espouse a cause of a particular constituency"); Holshouser v. Scott, 335 F. ,

Supp. 928 (D.D.C. 1971) ("We hold that the one man, one vote rule does not appl

to state judiciary...."); Buchanan v. Rhodes, 294 F. Supp. 860 (N.D. Ohio 1966r

("Judges do not represent people, they serve people"); New York State Assn. of

Trial Lawyers v. Rockefeller, 267 F. Supp. 148, 153 (S.D. N.Y. 1967) ("The state

judiciary, unlike the legislature, is not the the organ responsible for achieving

representative government.")

Plaintiffs rely principally on Haith v. Martin, 618 F. Supp. 410 (D.N.C. 1985)

(three-judge court), aff'd, without opinion, 106 S.Ct. 3268, 93 L.Ed.2d 559 (1986)

for the proposition that this Court should ignore Wells v. Edwards, supra, and

apply section 2 to the allegations contained in their complaint. 7/ In Haith,

the district court held that judicial election systems are covered by section 5

of the Voting Rights Act, which requires preclearance by the U.S. Justice

Department of any voting procedures changes in areas with a history of voting

discrimination. Plaintiffs, in essence, argue that because the Supreme Court,

without opinion, affirmed the Haith district court in its application of section

5 to judicial elections, this Court should expand the holding of Haith to include

section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. Plaintiffs' argument fails because section 5

does not specifically restrict its application to election systems pertaining to

representatives, a restriction included in the 1982 amendments to section 2.

Although a potential conflict may develop between the holdings in Wells

• and Haith, Wells clearly states the "one man one vote" principle is not applicable

• to judicial elections. This Court recognizes the long standing principle that

• the judiciary, on all levels, exists to interpret and apply the laws, that is,

judge the applicability of laws in specific instances. Representatives of the

people, on the other hand, write laws to encompass a wide range of situations.

Therefore, decisions by representatives must occur in an environment which takes

into account public opinion so that laws promulgated reflect the values of the

represented society, as a whole. Judicial decisions which involve the individual

or individuals must occur in an environment of impartiality so that courts render

7/ Plaintiffs also rely on Kirksey v. Allian, Civ. Act. No. J85-0960(B), slip op.

(S.D. Ms. April 1, 1987), in which a district court dismissed the reasoning in

Wells, and held section 2 does apply to the elected judiciary. Wells, supra, has

precedential authority and clearly conflicts with Kirksey, an untested 7371.Te7

court opinion.

-8-

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

RONALD CHISOM, ET AL CIVIL ACTION

VERSUS NO. 86-4075

EDWIN EDWARDS, ET AL SECTION: "A!"

§§§§§§§§§§§§ •

AMENDED OPINION

This matter is before the Court on defendants' motion to dismiss for failure

to state a claim upon which. relief can be granted pursuant to F.R.Civ.P. 12(b)(6).

For the,foregoing reasons, defendants' motion is GRANTED.

FACTS AND ALLEGATIONS

Ronald Chisom, four other black plaintiffs and the Louisiana Voter Regis-

tration Education Crusade filed this class action suit on behalf of all blacks

registered to vote in Orleans Parish. Plaintiffs' complaint challenges the

process of electing Louisiana Supreme Court Justices from the First District of

the State Supreme Court. The complaint alleges that the system of electing two

at-large Supreme Court Justices from the Parishes of Orleans, St. Bernard, Plaque-

mines and Jefferson violates the 1965 Voting Rights Act, as amended, 42 U.S.C.

§ 1973, the fourteenth and fifteenth amendments to the United States Federal Con-

stitution and, finally, 42 U.S.C. § 1983. Plaintiffs argue that the election

system impermissibly dilutes, minimizes and cancels the voting strength of

blacks who are registered to vote in Orleans Parish.

More specifically, plaintiffs' original and amended complaint avers that the

First Supreme Court District of Louisiana contains approximately 1,102,253 resi-

dents of which 63.36%, or 698,418 are white, and 379,101, or 34.4% are black.

The First Supreme Court District has 515,103 registered voters, of which 68%

are white, and 31.61% are black. Plaintiffs contend that the First Supreme

Court District of Louisiana should be divided into two single districts. Plain-

tiffs suggest that because Orleans Parish's present population is 555,515 persons,

roughly half the present First Supreme Court District, the most logical division

is to have Orleans Parish elect one Supreme Court Justice and the Parishes of

Jefferson, St. Bernard and Plaquemine together elect the other Supreme Court

Justice. If plaintiffs' plan were to be carried out, plaintiffs contend the

present First Supreme Court District encompassing only Orleans Parish would then

have a black population and voter registration comprising a majority of the

district's population. More specifically, plaintiffs assert presently 124,881 of

the registered voters in Orleans are white, comprising 47.9% of the plaintiffs'

proposed district's voters; while 134,492 of the registered voters in Orleans

are now black, comprising 51.6% of the envisioned district's voters. The other

district comprised of Jefferson, Plaquemines and St. Bernard Parishes and would

have a substantially greater white population than black, according to plaintiffs'

plan.

Plaintiffs seek class certification of approximately 135,000 black residents

of Orleans Parish, whom plaintiffs allege suffer from diluted voting strength as

a result of the present at-large election system. Additionally, plaintiffs seek

a preliminary and permanent injunction against the defendants restraining the

further election of Justices for the First Supreme Court District until this

Court makes a determination on the merits of plaintiffs' challenge. Further,

plaintiffs seek an order requiring defendants to reapportion the First Louisiana

Supreme Court in a manner which "fairly recognizes the voting strengths of . minor-

ities in the New Orleans area and completely remedies the present dilution of

minority voting strength." (Plaintiffs' Complaint, p. 7). Plaintiffs also seek

an order requiring compliance with the Voting Rights Act and, finally, a declara-

tion from this Court that the Supreme Court election system violates the voting

Rights Act and the fourteenth and fifteenth amendments to the Federal Constitu-

tion. 1/

Defendants do not dispute the figures presented by plaintiffs in their

amended complaint. Instead, they contend that section 2 of the Voting Rights

Act of 1965, as amended, the fourteenth and fifteenth amendments to the United

States Federal Constitution and 42 U.S.C. § 1983 fail to provide plaintiffs grounds

upon which relief can be granted for plaintiffs' allegation of diluted black

voting strength.

SECTION 2 OF THE VOTING RIGHTS ACT OF 1965 DOES NOT APPLY TO THE INSTANT ACTION

Prior to 1982, section, 2 of the Voting Rights Act (42 U.S.C. § 1973), "Denial

or Abridgement of Rights to: Vote on Account of Race or Color Through Voting

Qualifications or Prerequisites," read as follows:

No voting qualification or prerequisite to voting, or

standard, practice, or procedure, shall be imposed or

applied by any State or political subdivision to deny or

abridge the right of any citizen of the United States to

vote on account of race or color, or in contravention of

the guarantees set forth in section 1973b(f)(2) of

this title.

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act was amended as a response to City of Mobile,

Alabama v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55, 100 S.Ct. 1490, 64 L.Ed. 47 (1980), in which the

Supreme Court in a plurality opinion held to establish a violation of section 2

of the Voting Rights Act, minority voters must prove the contested electoral

mechanism was intentionally adopted or maintained by state officials for a

discriminatory purpose. After Bolden, Congress in 1982 revised section 2 to

make clear that a violation of the Voting Rights Act could be proven by showing a

discriminatory effect or result alone. United States v. Marengo County Commis-

sion, 731 F.2d 1546 n.1 (11th Cir. 1984), appeal dismissed, cert. denied, 105

1/ Plaintiffs, earlier, sought a three judge court to hear this complaint which

was denied by this Court as the terms of 28 U.S.C. § 2284 provide for a three

judge court when the constitutionality of the apportionment of congressional

districts or the apportionment of any statewide legislative body is challenged.

Nowhere does § 2284 provide for convening a three judge court when a judicial

apportionment is challenged.

•

S.Ct. 375, 83 L.Ed.2d 311. (1984) 2/ Section 2, as amended, 96 Stat. 134, now

reads:

(a) No voting qualification or prerequisite to voting or

standard, practice, or procedure shall be imposed or applied

by any State or political subdivision in a manner which

results in a denial or abridgement of the rights of any

citizen of the United States to vote on account of race or

color, or in contravention of the guarantees set forth in

section 1973b(f)(2), as provided in subsection (b) of this

section.

(b) A violation of subsection (a) is established if, based

on the totality of the circumstances, it is shown that the

political processes leading to nomination for election in the

State or political subdivision are not equally open to par-

ticipation by members of a class of citizens protected by

subsection (a) of this section in that its members have less

opportunity than other members of the electorate to partici-

pate in the political process and to elect representatives

of their choice. The extent to which members of a protected

class have been elected to office in the State or political

subdivision is one circumstance which may be considered:

Provided, that nothing in this section establishes a right

to have members of a protective class elected in numbers

equal to their proportion in the population.

42 U.S.C. § 1973 (emphasis added).

Prior to the 1982 amendments to section 2, a three-judge court composed of

Judges Ainsworth, West and Gordon, headed by Judge West, addressed a voting rights

claim arsing out of the same claims of discrimination as in this case, albeit not

in a section 2 context. Wells v. Edwards, 347 F. Supp. 453 (M.D. La. 1972), aff'd,

409 U.S. 1095, 93 S.Ct. 904, 34 L.Ed.2d 679 (1973). In Wells, a registered black

voter residing in Jefferson Parish, brought suit seeking a reapportionment of

the judicial districts from which the seven judges of the Supreme Court of Louisiana

are elected. Ms. Wells sought an injunction enjoining the state from holding the

scheduled Supreme Court Justice elections and an order compelling the Louisiana

Legislature to enact an apportionment plan in accordance with the "one man, one

2/ See S.Rep. 97-417, 97 Cong.2d Sess (1982) pp. 15-43 for a complete discus-

sion of Congress' intent to overturn the section 2 "purposeful discrimination"

requirement imposed by Mobile v. Bolden.

-4-

vote" principle and to reschedule the pending election. On cross motions for

summary judgment, the three-judge court stated, "We hold that the concept of

one-man, one vote apportionment does not apply to the judicial branch of govern-

ment." 342 F. Supp. at 454. The Wells court took notice of Hadley v. Junior

College District, 397 U.S. 50, 90 S.Ct. 791, 25 L.Ed.2d 45 (1970), in which the

Supreme Court held, "Whenever a state or local government decides to select

persons by popular election to perform *governmental functions, the equal protec-

tion clause of the fourteenth amendment requires that each qualified voter must

be given an equal opportunity to participate in that election....", 90 S.Ct.

791, 795 (emphasis added), but distinguished its holding by outlining the special

functions of judges.

The Wells court noted many courts' past delineations between elected officials

who performed legislative or executive functions and judges who apply, but not

create, law 3/ and concluded:

'Judges do not represent people, they serve people.'

Thus, the rationale behind the one-man, one-vote

principle, which evolved out of efforts to preserve a

truly representative form of government, is simply not

relevant to the makeup of the judiciary.

347 F. Supp. at 455.

The Wells opinion interpreted the "one man one vote" principle prior to the

1982 amendments to section 2, which added the phrase, "[T]o elect representatives

3/ See, e.g., Stokes v. Fortson, 234 F. Supp. 575 (N.D. Ga. 1964) ("Manifestly,

judges and prosecutors are not representative in the same sense as they are

legislators or the executive. Their function is to administer the law, not to

espouse a cause of a particular constituency"); Holshouser v. Scott, 335 F.

Supp. 928 (D.D.C. 1971) ("We hold that the one man, one vote rule does not apply

to state judiciary...."); Buchanan v. Rhodes, 294 F. Supp. 860 (N.D. Ohio 1966)

("Judges do not represent people, they serve people"); New York State Assn. of

Trial Lawyers v. Rockefeller, 267 F. Supp. 148, 153 (S.D. N.Y. 1967) ("The state

judiciary, unlike the legislature, is not the the organ responsible for achieving

representative government.")

of their choice." 4/ (See emphasis in quotation 42 U.S.C. 1973, supra.) The

legislative history of the 1982 Voting Rights Act amendments does not yield a

definitive statement noting why the word "representative" was added to section

2. However, in this case, no such statement is necessary, as "to elect represen-

tatives of their choice" is clear and unambigous.

Judges, by their very definition, do not represent voters but are "appointed

[or elected] to preside and to administer the law." Black's Law Dictionary, 1968.

As statements by Hamilton in the Federalist, No. 78 reflect, the distinction be-

tween Judge and representative has long been established in American legal his-

tory:

If it be said that the legislative body are themselves the

constitutional judges of their own powers, and that the

construction they put upon them is conclusive upon the

other departments, it may be answered, that this cannot be

the natural presumption, where it is not to be collected

from any particular provisions in the constitution. It is

not otherwise to be supposed that the constitution could

intend to enable the representatives of the people to substi-

tute their will to that of their constituents. It is far

more rational to suppose that the courts were designed to

be an intermediate body between the people and the legisla-

ture, in order, among other things, to keep the latter

within the limits assigned to their authority. The inter-

pretation of the laws is the proper and peculiar province

of the courts....

Indeed, our Federal Constitution recognizes the inherent difference between

representatives and judges by placing the federal judiciary in an entirely

different category from that of other federal elective offices. It is noteworthy

that articles 1 and 2, which establish Congress and the Presidency, are lengthy

and detailed, while Article 3, which establishes the judiciary, is brief and free

of direction, indicating the judiciary is to be free of any instructions. Today,

Fifth Circuit jurisprudence continues to recognize the long established dis-

tinction between judges and other officials. See, e.g., Morial v. Judiciary

4/ This language did not appear in section 2 at the time of the Wells opinion.

Committee of State of Louisiana, 565 F.2d 295 (5th Cir. 1977) en banc, cert.

denied, 435 U.S. 1013, 98 S.Ct. 1887 (1978). (See also Footnote 1/, supra.)

The legislative history of the Voting Rights Act Amendments does not address

the issue of section 2 applying to the judiciary, 5/ indeed, most of the discus-

sion concerning the application of the Voting Rights Act refers to legislative

offices. Nevertheless plaintiffs ignore the historical distinction between

representative and judge and the lack of any discernible legislative history in

their favor and argue that the Voting Rights Act is a broad and remedial measure

which must be extended to cover judicial election systems. 6/

5/ The Chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee's Subcommittee on the Consti-

tution, , Senator Orrin Hatch, in voicing his strong opposition of the Legislative

reversal of Bolden through the section 2 revisions, made a brief reference to

section 2 4177171-g- to judicial elections:

Every political subdivision in the United States would be

liable to have its electoral practices and procedures

evaluated by the proposed results test of section 2. It is

important to emphasize at the onset that for the purposes of

Section 2, the term "political subdivision" encompasses all

governmental units, including city and county councils,

school boards, judicial districts, utility districts, as

well as state legislatures.

S. Rep. 97-417, 97 Cong. 2d Sess. 127, 151, reprinted in 1982 U.S. Code Cong. &

Admin. News 298, 323.

Although Senator Hatch's comment indicates coverage of judicial districts by the

Voting Rights Act, the purpose of the above passage was to illustrate Senator

Hatch's belief that the impact of the section 2 Amendments' "results test" would

be far ranging and in his opinion, detrimental. Senator Hatch's comments were

included at the end of the Senate report usually reserved for dissenting Senators.

The above passage did not portend to be a definative or even a moderately detailed

description of the coverage of the Voting Rights Act, nor does Senator Hatch

provide any authority for his suggestion of the potential scope of section 2.

Rather, this Court finds that the passage was meant to be argumentative and

persuasive, and not as a means to define actual scope of the Act.

6/ See e.g., United Jewish Organization of Williamsburg, Inc. v. Carey, 430

U.S. 144, 97 S.Ct. 996, 51 L.Ed.2d 229 (1977) ("It is apparent from the face of

the Act, from its legislative history, and from our cases of the Act itself was

broadly remedial in the sense that it 'was designed by Congress to banish the

blight of racial discrimination in voting...'"), 130 U.S. at 156; South Carolina

V. Katzenback, 383 U.S. 301, 86 S.Ct. 803 (1966) (The Voting Rights Act "reflects

Congress' firm intention to rid the country of racial discrimination in voting"),

383 U.S. at 315.

-7-

Plaintiffs rely principally on Haith v. Martin, 618 F. Supp. 410 (D.N.C. 1985)

(three-judge court), aff'd, without opinion, 106 S.Ct. 3268, 93 L.Ed.2d 559 (1986)

for the proposition that this Court should ignore Wells v. Edwards, supra, and

apply section 2 to the allegations contained in their complaint. 7/ In Haith,

the district court held that judicial election systems are covered by section 5

of the Voting Rights Act, which requires preclearance by the U.S. Justice

Department of any voting procedures changes in areas with a history of voting

discrimination. Plaintiffs, in essence, argue that because the Supreme Court,

without opinion, affirmed the Haith district court in its application of section

5 to judicial elections, this Court should expand the holding of Haith to include

section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. Plaintiffs' argument fails because section 5

does not specifically restrict its application to election systems pertaining to

representatives, a restriction included in the 1982 amendments to section 2.

Although a potential conflict may develop between the holdings in Wells

and Haith, Wells clearly states the "one man one vote" principle is not applicable

to judicial elections. This Court recognizes the long standing principle that

the judiciary, on all levels, exists to interpret and apply the laws, that is,

judge the applicability of laws in specific instances. Representatives of the

people, on the other hand, write laws to encompass a wide range of situations.

Therefore, decisions by representatives must occur in an environment which takes

into account public opinion so that laws promulgated reflect the values of the

represented society, as a whole. Judicial decisions which involve the individual

or individuals must occur in an environment of impartiality so that courts render

7/ Plaintiffs also rely on Kirksey v. Allian, Civ. Act. No. J85-0960(B), slip op.

(S.D. Ms. April 1, 1987), in which a district court dismissed the reasoning in

Wells, and held section 2 does apply to the elected judiciary. Wells, supra, has

precedential authority and clearly conflicts with Kirksey, an untested lower

court opinion.

•

judgments which reflect the particular facts and circumstances of distinct

cases, and not the sweeping and sometimes undisciplined winds of public opinion.

PLAINTIFFS' FOURTEENTH AND FIFTEENTH AMENDMENT CLAIMS FAIL TO STATE A CLAIM

UPON WHICH RELIEF CAN BE GRANTED AS PLAINTIFFS DO NOT PLEAD DISCRIMINATORY INTENT

The appropriate constitutional standard for establishing a violation of the

fourteenth amendment in the context of voting rights is "purposeful discrimination."

village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Corp., 429 U.S. 252, 97

S.Ct. 555, 50 L.Ed.2d 450 (1977); 8/ McMillian v. Escambia City, Fla, 688 F.2d

960 (5th Cir. 1982). 9/ Similarly, City of Mobile, Alabama v. Bolden, supra,

requires a court to establish a finding of discriminatory purpose before declaring

a fifteenth amendment violation of voting rights. 10/

In Voter Information Project, 612 F.2d 208 (5th Cir. 1980), a panel composed

of Judges Jones, Brown and Rubin (opinion by Judge Brown) held a suit that alleged

8/ In Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Corp., purposeful

discrimination was held the standard necessary to establish a violation of the

fourteenth amendment where plaintiff claimed a village rezoning decision was

racially discriminatory.

9/ In McMillian v. Escambia City, Fla., the Fifth Circuit held the Arlington

Heights' "purposeful discrimination" standard is appropriate in fourteenth

amendment voter discrimination claims.

10/ Although there is a conflict between the requirement of "discriminatory

effect" in Section 2, which is intended to enforce the fifteenth amendment, and

the requirement of "purposeful discrimination" for a fifteenth amendment violation

standing alone, the Senate Judiciary Committee addressed this point and recognized

Congress' limited ability to adjust the burden of proving Voting Rights Violations

in its "Voting Rights Act Extension" Committee Report.

Certainly, Congress cannot overturn a substantive inter-

pretation of the Constitution by the Supreme Court. Such

rulings can only be altered under our form of government by

constitutional amendment or by a subsequent decision by the

Supreme Court.

Thus Congress cannot alter the judicial interpretations

in Bolden of the fourteenth and fifteenth amendments by

simple statute. But the proposed amendment to Section 2

does not seek to reverse the court's constitional inter-

pretation.

(Continued on p. 10)

-9-

the at-large scheme for electing city judges in Baton Rouge invidiously diluted

the voting strength of black persons in violation of the fourteenth and fifteenth

amendments to the United States Federal Constitution, and 42 U.S.C. § 1983, could

not be dismissed when 'the complaint alleges purposeful discrimination. At the

trial level, Judge West relied on his reasoning in Wells, supra, that the one

man, one vote principle did not apply to the elections of judges, and dismissed

plaintiffs' suit. Judge Brown reversed, holding that the "one man, one vote"

principle as espoused in Wells, supra, was not enough to dismiss plaintiff's

complaint. The Voter Information Court found:

The problem with the District Court's opinion, however,

is that it assumes the "one man, one vote" principle

was the exclusive theory of plaintiff's complaints. In

addition to a rather vaguely formulated "one man, one

vote" theory, plaintiffs contend that both in design

and operation, the at-large schemes dilute the voting

strength of black citizens and prevent blacks from

being elected as judges. As the complaint attacking

the city judge election system alleges:

25. The sole purpose of the present at-large

system of election of City Judge is to

insure that the white majority will continue

to elect all white persons for the offices

of City Judge.

26. The present at-large system was insti-

tuted when "Division B" was created as a

reaction to increasing black voter regis-

tration and for the express purpose of

diluting and minimizing the effect of the

increased black vote.

27. In Baton Rouge, there is a continuing

history of "bloc voting" under which when

a black candidate opposes a white candidate,

the white majority consistently casts its

votes for the white candidate, irrespective

of the relative qualifications.

Fn. 10 Continued:

S.Rep. 97-417, 97 Cong. 2d Sess. (1982), p. 41.

The Supreme Court, the only body empowered to interpret the Federal Constitution,

has not seen fit to overrule its repeated determination that the fourteenth and

fifteenth amendments claims require "purposeful discrimination."

-10-

Plaintiffs contend that since most of the black popula-

tion of Baton Rouge and E. Baton Rouge Parish is concen-

trated in a few geographic areas, black citizens could,

under a single member district plan, elect at least some

black judges.

612 F.2d at 211.

The Voter Information Project Court held the plaintiff's complaint contained

sufficient allegations of intentional discrimination against black voters to

survive a motion to dismiss: "If plaintiffs can prove that the purpose and opera-

tive effect of such purpose of the at-large election schemes in Baton Rouge is to

dilute the voting strength of black citizens, then they are entitled to some form

of relief." 612 F.2d at 212. Thus, the Voter Information Project requires that

"purpose and operative effect" be pled in a fourteenth and fifteenth amendment

challenge to a judicial apportionment plan.

The complaint in the instant case states, in pertinent part:

Because of the offical history of racial discrimination

in Louisiana's First Supreme Court District, the

wide spread prevalence of racially polarized voting

in the district, the continuing effects of past dis-

crimination on the plaintiffs, the small percentage

of minorities elected to public office in the

area, the absence of any black elected to the

Louisiana Supreme Court from the First District, and

the lack of any justifiable reason to continue the

practice of electing two Justices at-large from

the New Orleans area only, plaintiffs contend that

the current election procedures for selecting

Supreme Court justices from the New Orleans area

dilutes minority voting strength and therefore

violates the 1965 Voting Rights Act, as amended.

(See Plaintiffs' Complaint, p.5). Later on, the Complaint alleges:

The defendants actions are in violation of the

Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendment to the United

States Constitution and 42 U.S.C. § 1983 in that

the purpose and effect of their actions is to

dilute, minimize, and cancel the voting strength

of the plaintiffs.

(Id., p. 6.)

Although "purpose and effect" language in the second quotation above broadly read

may imply plaintiffs' intention to plead discriminatory intent, it is this Court's

considered opinion, based on the complaint as a whole, that plaintiffs intend to

prove this claim based on a theory of "discriminatory effect" and not on a theory

of "discriminatory intent." City of Mobile Alabama v. Bolden, supra. For example,

plaintiffs' complaint does not allege the system by which the Louisiana Supreme

Court Justices are elected was instituted with specific intent to discriminate.,

This contrasts with the specific allegations in voter Information Project, supra.

Accordingly, plaintiffs lack the requisite allegations in order to prove a

violation of the fourteenth or fifteenth amendment to the Federal Constitution.

The Court reserves the right for plaintiffs to reurge its fourteenth and

fifteenth amendment claims as they relate to the Court's ruling that plaintiffs'

complaint only alleges "discriminatory effect."

Accordingly, unless plaintiffs' complaint is amended within then (10) days

of the entry of this opinion, the Clerk of Court is directed to enter judgment

judgment DISMISSING plaintiffs' claim at their cost.

New Orleans, Louisiana, this 1st day of May , 1987.

/s/

CHARLES SCHWARTZ, JR.

UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE