Burgess v Hampton Motion for Leave to File Memorandum Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1976

16 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Burgess v Hampton Motion for Leave to File Memorandum Amicus Curiae, 1976. f85d0713-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ccfc0ce6-ce4c-437b-9145-b04604844870/burgess-v-hampton-motion-for-leave-to-file-memorandum-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

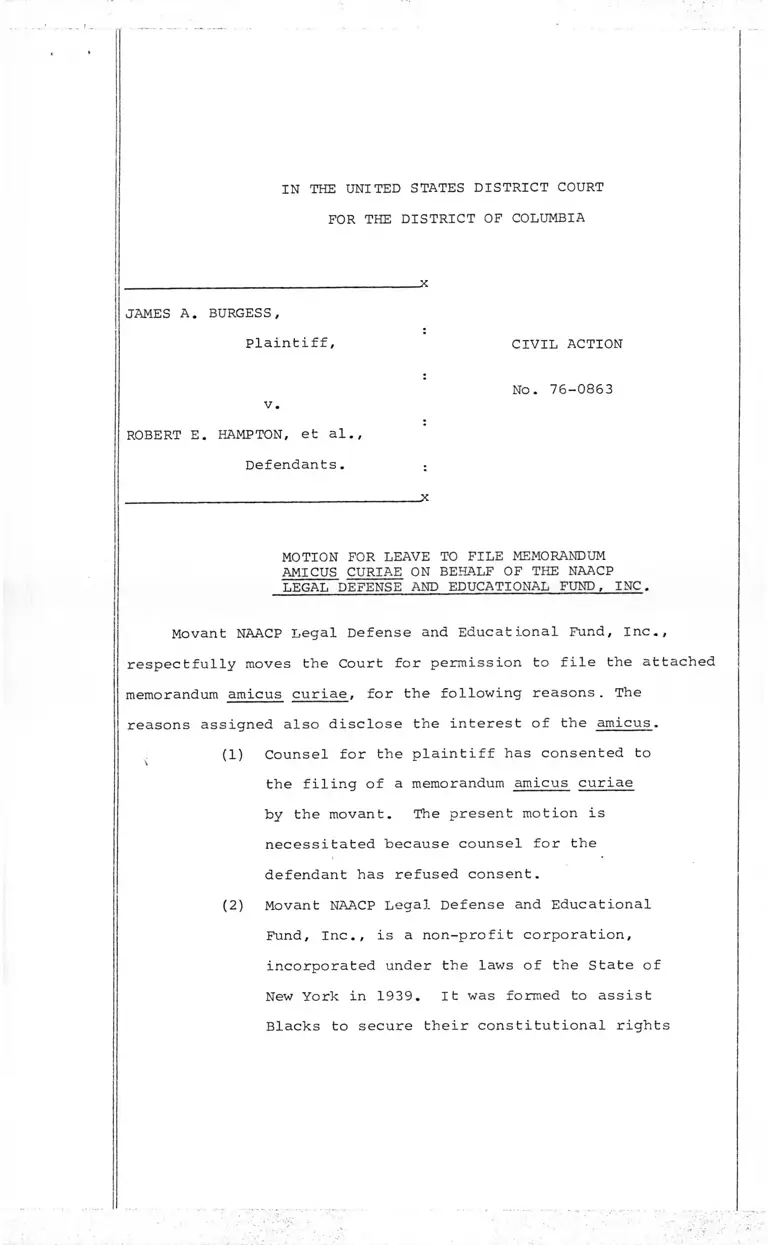

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

JAMES A. BURGESS,

Plaintiff,

v.

ROBERT E. HAMPTON, et al

Defendants.

CIVIL ACTION

No. 76-0863

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE MEMORANDUM

AMICUS CURIAE ON BEHALF OF THE NAACP

LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

Movant NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.,

respectfully moves the Court for permission to file the attached

memorandum amicus curiae, for the following reasons. The

reasons assigned also disclose the interest of the amicus.

(1) Counsel for the plaintiff has consented to

the filing of a memorandum amicus curiae

by the movant. The present motion is

necessitated because counsel for the

defendant has refused consent.

(2) Movant NAACP Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc., is a non-profit corporation,

incorporated under the laws of the State of

New York in 1939. It was formed to assist

Blacks to secure their constitutional rights

1 / E.g C . A . No.

by the prosecution of lawsuits. Its charter

declares that its purposes include rendering

legal aid gratuitously to Blacks suffering

injustice by reason of race who are unable, on

account of poverty, to employ legal counsel on

their own behalf. The charter was approved

by a New York Court, authorizing the organi

zation to serve as a legal aid society. The

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

(LDF), is independent of other organizations

and is supported by contributions from the

public. For many years its attorneys have

represented parties and has participated as

amicus curiae in the federal courts in cases

involving many facets of the law.

(3) Attorneys employed by amicus are counsel

for plaintiffs in more than thirty (30) cases

brought under Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964 against government agencies through

out the nation, including a number in this

_!/district. Thus, we have a direct interest in

the question presented by the government's motion

seeking an award of counsel fees against an un

successful plaintiff.

, Barrett v. United States Civil Service Commission,

74-1694

- 2 -

(4) Attorneys for amicus have been primarily

responsible for the development of the law

regarding counsel fee awards under the various

Civil Rights Acts, having represented plaintiffs

in the leading cases of Newman v. Piggie Park

Enterprise, 390 U.S. 400 (1968); Northcross

v. Memphis Board of Education, 412 U.S. 427 (1973),

Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond

416 U.S. 696 (1974) and Johnson v. Georgia

Highway Express, Inc., 488 F.2d 714 (5th Cir.

1974). Therefore, we believe that Our views

on the important question before the Court

will be helpful in its resolution.

WHEREFORE, for the foregoing reasons

we move that the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc. be given leave to file the attached memorandum amicus curiae.

Respectfully submitted,

DAVID CASHDAN1712 "N" Street, N.W.

Washington, D. C. 20036

Tel. No. 202-833-9070

JACK GREENBERG

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

MELVYN R. LEVENTHAL

BILL LANN LEE

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Tel. No. 212-586-8397

Counsel for Amicus Curiae

-3-

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

JAMES A. BURGESS,

Plaintiff,

v.

ROBERT E. HAMPTON, et al.,

Defendants.

CIVIL ACTION

NO. 76-0863

MEMORANDUM OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., AS AMICUS

CURIAE IN OPPOSITION TO DEFENDANTS'

MOTION FOR ATTORNEY'S FEES.

I.

Introduction

We will urge in some detail below two reasons v/hy the

government's motion for counsel fees should be denied. First,

the statute clearly prohibits such an award; and, second, even

if the government might be entitled to an award under some cir

cumstances as a defendant in a Title VII action, it cannot ob

tain an award in this case under well-established principles.

Preliminarily, however, we wish to urge the Court that the grant

ing of the government's motion would undermine totally the basic

policy behind allowing counsel fee awards in Title VII actions.

The purpose of the fee provision is to encourage the bring

ing of Title VII cases because plaintiffs act in the capacity of

"private attorneys general," enforcing a congressional policy of

great importance. This is particularly the case in a Title VII

action against federal government agencies because a private

party is the only "attorney general" in such an instance, in con

trast with the situation where a defendant is a private employer

or a state or local government agency where the federal govern

ment through either the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

or the Attorney General can bring suit. Thus, to assess attorneys'

fees against a plaintiff in an action brought where the govern

ment is a defendant could only have the effect of intimidating

potential plaintiffs and discouraging them from exercising their

rights under Title VII. Since there is no other possible

plaintiff to enforce Title VII judicially against federal agencies

such a result would seriously interfere with the carrying out of

the Congressional policy of uprooting discrimination in all em

ployment .

We urge, therefore, that not only should the government's

position be rejected in this case, but that the Court should

make it unequivocally clear that under no circumstances can such

attorneys' fees be awarded, so that even the threat of such an

award will be dispelled once and for all.

II.

TITLE VII SPECIFICALLY PROHIBITS

AWARDS OF COUNSEL FEES TO THE

___________GOVERNMENT__________

The language of 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(k) makes it clear that

a governmental agency head cannot be awarded counsel fees.

The section provides:

_ 1 /

1/ Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, 390 U.S. 400 (1968).

-2-

"In any action or proceeding under this sub

chapter the court, in its discretion, may allow the prevailing party, other than the Commission

or the United States, a reasonable attorney's

fee as part of the costs, and the Commission and

the United States shall be liable for costs the

same as a private person."

Amicus finds it difficult to understand the government's argu-

------------ 2J

ment why it nevertheless is entitled to counsel fees. It seems

to be based on a wholly unwarranted premise that the United

States is not going to receive, in fact, any counsel fee award

since the nominal defendant in the action is the Secretary of the

Treasury and not the United States. This is not the first time

such a construction of the statute has been urged. Its reverse

was used in an attempt to avoid payment of counsel fees where the

government had lost a Title VII action as the defendant. Thus,

it was argued that since sub-section (k) makes the United States

liable for costs, and since the head of an agency was the named

defendant and not the United States, no counsel fees could be

awarded against that defendant. This argument was rejected by

the Courts and was abandoned by the Department of Justice in the

face of great criticism. See, letter from Irving Jaffe, Acting

_3/Assistant Attorney General to Senator John Tunney, May 6, 1975.

The argument in its present guise has no more basis than it did

before, as may be shown by a simple question: To whom will the

moneys from an award of counsel fees go? It will certainly not

be payable to the United States Attorneys personally, and it

2/ The government here relies primarily on footnote 15 of

Grubbs v. Butz, 12 E.P.D. 1[ 11,090 (D.C.C. 1975) . With all

respect to the Court of Appeals, the footnote is pure dicta, in

which Judge MacKinnon declined to concur. In any event, the

footnote does not state that the government can receive counsel

fees, but only says that it "is at least uncertain" that it

can not.

3/ The letter was printed in full in the New Developments

section of CCH Employment Practice Guide at 1f 5327, but no longer

appears there. We have appended to this memorandum an excerpt

from SNA's Daily Labor Report Current Developments Section (May

13, 1975), that quotes the letter in its entirety.

-3-

will certainly not be payable to Mr. Simon; it will in fact be

payable to the Treasury of the United S tates of America as is

the case whenever costs are awarded in action involving the head

of a government agency. Indeed, the defendants acknowledge

as much in their memorandum when they calculate the amount of

counsel fees by determining "their cost to the government." In

short, who the named defendant is is irrelevant; just as any

award of counsel fees against an agency head is paid by the

United States in fact, so any award in his favor will be paid to

the United States in fact, and therefore will be an award of

attorneys' fees in its favor.

The legislative history of the 1972 amendments to Title

VII is of no help to the government. The extension of 2000e-5(k)

to suits against governmental agencies was not useless, since

its effect was to allow counsel fees against the government. The

refusal to limit counsel fees to "prevailing plaintiffs" did no

more than to permit the awards to private or state or local

defendants under the limited circumstances discussed below.

Since Congress had already specificially provided in 5 (k) that

the United States could not receive counsel fees, it would have

been redundant to say it again.

Finally, the government does not dispute that it can not

receive counsel fees when it is the successful plaintiff in a

Title VII action. This is so even when the defendant would be

the United States Steel Corporation or the State of California,

to give examples of institutions with ample legal resources.

If a defendant who has violated Title VII can not be made to

1/bear the costs of the litigation, how could Congress have pos

sibly intended that a federal employee seeking redress against

his government be so burdened.

4/ In an action such as United States v. United States Steel,

■520 F. 2d 1043 (5th Cir. 1975) , the costs are incomparably greater

than the $1,010.10 sought to be squeezed out of the plaintiff

here.

-4-

Ill.

COUNSEL FEES MAY NOT BE AWARDED

IN THIS CASE __________

Even under the wholly unwarranted assumption that counsel

fees might be awarded against the government under some cir

cumstances, they cannot be in this case. The government argues

at some length that the standard for awarding counsel fees

to a defendant in a Title VII action is essentially the same

as that for the awarding of fees to a plaintiff. This is simply

not the case. It is established beyond any question that a

prevailing defendant may receive fees only if the action is

vexatious or frivolous, if the plaintiff has instituted it to

harass or embarass, or if the plaintiff is motivated by malice

or vindictiveness. In other words, fees are permissible

if the action is brought in bad faith. United States Steel

Corp. v. United States, 519 F.2d 359, 364 (3d Cir. 1975);

Carrion v. Yeshiva University, 535 F.2d 722 (2d Cir. 1976);

Wright v. Stone Container Corp. , 524 F.2d 1058 (8 th Cir. 1975).

The position of the government here is directly con

trary to that recently taken before the House of Representatives

in testimony regarding the recently enacted Civil Rights

Attorneys' Fees Awards Act of 1976 (P.L. No. 94-559). Rex E. Lee,

Assistant Attorney Gernal of the United States in charge of

the Civil Division told a House Subcommittee that it was the

position of the government that counsel fees "be restricted

to the prevailing plaintiff, in order to prevent a possible

5

In responsechilling effect on these [civil rights] actions."

to a subcommittee inquiry, Mr. Lee further stated that it was

the Department's position that when the government was the

plaintiff counsel fees should be awarded a prevailing defendant

only where it is shown that the government brought the action

§/in "bad faith, harassment or intimidation."

Although it is not directly applicable, the legislative

history of the Civil Rights Attorneys' Fees Awards Act of 1976

is instructive in revealing Congressional intent with regard

to those circumstances when defendants may receive attorneys'

fees. See, Hickman v. Fincher, 483 F.2d 855, 857 (4th Cir. 1973)

The new attorneys' fee bill was passed to fill at least part of

the gap created by the Supreme Court's decision in Alyeska

Pipeline Service Co. v. Wilderness Society. 421 U.S. 240 (1975).

The Alyeska case held that in the absence of statutory authoriza

tion, counsel fees could be awarded in only very limited

circumstances. In the course of its opinion, the Supreme Court

disapproved of lower court decisions which held that the same

standards for awarding counsel fees that prevailed in actions

brought under ..the Civil Rights Act of 1964, including Title VII,

applied in actions brought under the Civil Rights Act of 1866,

42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 and 1982. 421 U.S. at 270, n. 46.

5/

5/ Transcript of testimony before the House Sub-Committee on

Courts, Civil Liberties and the Administration of Justice,

Committee on the Judiciary, December 3, 1975 on H.R. 8220 and

H.R. 9552, transcript p. 127.

6/ This position was set out in a letter dated January 23, 1976

by Rex E. Lee, Assistant Attorney General, Civil Division, United

States Department of Justice, in response to an inquiry made in a

letter of December 10, 1975 from the Honorable Robert W. Kasten-

meier, Subcommittee on Courts, Civil Liberties, and the

Administration of Justice, Committee on the Judiciary, House of

Representatives. See, 122 Cong. Rec. H. 12162 (daily edition,

October 1, 1976). Mr. Lee also testified before the subcommittee

that: . . . frivolous positions are also asserted

by the government's adversaries in litigation.

We are not asking that the government be

awarded attorneys' fees in such cases . . . . Testimony cited in n. 4, supra,_a^ p. 124.

Congress considered that Alyeska had created an anomalous

situation and passed Public Law 94-559 in order to bring about

uniformity in the entitlement to counsel fees for all civil rights

litigation. In both the House and Senate Reports and on the floor

of both Houses, considerable attention was given to the standards

under which fees might be awarded to both plaintiffs and de

fendants. Throughout, citations were made to cases arising under

Titles II and VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Congress'

intention was clearly to cofify and incorporate that body of law.

The House Report, for example, states:

Under H.R. 15460, either a prevail

ing plaintiff or a prevailing de

fendant is eligible to receive an award of

fees. Congress has not always been that

generous. In about two-thirds of the

existing statutes, such as the Clayton

Act and the Packers and Stockyards Act,

only prevailing plaintiffs may recover

their counsel fees. This bill follows

the more modest approach of other civil

rights acts.

It should be noted that when the

Justice Department testified in support

of H.R. 9552, the precedessor to

H.R. 15460, it suggested an amendment

to allow recovery only to prevailing

plaintiffs. Assistant Attorney General

Lee thought the phrase "prevailing

party" might have a "chilling effect"

on civil rights plaintiffs, discourag

ing them from initiating law suits.The Committee was very concerned with

the potential impact such a phrase

might have on persons seeking to

vindicate these important rights

under Federal law. In light of exist

ing case law under similar provisions,

however, the Committee concluded

that the application of current

standards to this bill will signifi

cantly reduce the potentially adverse

affect on the victims of unlawful

- 7 -

conduct who seek to assert their

federal claims. H. Report No.

94-1558 on H.R. 15460, at p.6.

Following a discussion of the liberal standard for awarding

plaintiffs their counsel fees the Report continues:

Consistent with this rationale, the courts

have developed a different standard for

awarding fees to prevailing defendants be

cause they do "not appear before the court

cloaked in a mantle of public interest."

United States Steel Corp. v. United States,

519 F.2d 359, 364 (3rd Cir. 1975). As

noted earlier such litigants may, in proper circumstances, recover their

counsel fees under H.R. 15460. To

avoid the potential "chilling effect"

noted by the Justice Department and

to advance the public interest articu

lated by the Supreme Court, however,

the courts have developed another test

for awarding fees to prevailing de

fendants. Under the case law, such an

award may be made only if the action

is vexatious and frivolous, or if the

plaintiff has instituted it solely

"to harass or embarrass" the defendant.

United States Steel Corp. v. United

States, supra at 364. If the plaintiff

is "motivated by malice and vindictive

ness," then the court may award counsel

fees to the prevailing defendant. Car

rion v. Yeshiva University, 535 F.2d

722 (2d Cir. 1976). Thus if the action

is not brought in bad faith, such fees

should not be allowed. See, Wright v.

Stone Container Corp. 524 F.2d 1058

(8th Cir.1975); see also Richardson v.

Hotel Corp. of America, 332 F. Supp.

519 (E.D.La. 1971), aff'd without

published opinion, 468 F.24 951 (5th

Cir. 1972). This standard will not

deter plaintiffs from seeking relief

under these statutes, and yet will

prevent their being used for clearly

unwarranted harassment purposes. Id.

at 6-7.

Interestingly, the Committee addressed specifically the

question of the standard when governmental officials are

defendants. It stated:

8

With respect to the awarding of

fees to prevailing defendants, it

should further be noted that govern

mental officials are frequently the

defendants in cases brought under

the statutes covered by H.R. 15460.

See, e.q., Brown v. Board of

Education, supra; Gautreaux v.

Hills, supra; 0 1 Connor v. Donaldson,

supra. Such governmental entities

and officials have substantial

resources available to them through

funds in the common treasury, includ

ing the taxes paid by the plaintiffs

themselves. Applying the same standard

of recovery to such defendants would

further widen the gap between citizens

and government officials and would

exacerbate the inequality of litigating

strength. The greater resources avail

able to governments provide an ample

base from which fees can be awarded

to the prevailing plaintiff in suits

against governmental officials or

entitles.

The facts of this case do not establish that the action

was brought for frivolous reasons or in an attempt to harass or

intimidate the federal government. indeed, the notion, that a

lone government employee could intimidate the federal govern

ment, particularly the Internal Revenue Service, is somewhat

absurd. This Court's opinion on the merits, although holding

that plaintiff's claim is not meritorious, indicates that there

was sufficient basis for it to require its full consideration

and that the action therefore was not frivolous. Thus the

facts here fall far short of those in Carrion v. Yeshiva

University, supra, where the district court found the action to

be malicious, and that the plaintiff had perjured herself in an

attempt to support a wholly baseless claim.

9

IV.

PLAINTIFF IS ENTITLED TO AN AWARD

OF COUNSEL FEES FOR SUCESSFULLY

DEFENDING AGAINST THE GOVERNMENT’S

MOTION

It is well established that counsel fees are to be awarded

to a private plaintiff in proceedings dealing with counsel fees

itself. See, e.g■ , Miller v. Amusement Enterprises, Inc., 426

F.2d 534 , 539 (5th Cir. 1970) ; Davis v. Board of School Commis

sioners of Mobile County, 526 F.2d 865, 868 (5th Cir. 1976).

These cases, of course, involved instances where the plaintiff

had prevailed on the merits and was entitled to counsel fees

on that basis. Nevertheless, the reasons are fully applicable

to the present case. Indeed, under the standard set out in

Newman v. Piggie Bark Enterprises, supra, counsel fees are

mandated to prevent Title VII litigation from being discouraged.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the Motion for Attorneys'

Fees should be denied.

Respectfully submitted,

DAVID CASHDAN

1712 "N" Street, N.S.

Washington, D.C. 20036

Tel. No. 202-833-9070

JACK GREENBERG

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

MELVYN R. LEVENTHAL

BILL LANN LEE

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Tel. No. 212-586-8397

Counsel for Amicus Curiae

- 10 -

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that I have served copies of the

attached MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE MEMORANDUM AMICUS CURIAE

and MEMORANDUM AMICUS CURIAE on counsel for the parties by

depositing the same in the United States Mail, United State

postage prepaid, addressed as follows:

LAWRENCE S. LAPIDUS, esq.

1801 "K" Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20006

EARL J. SILBERT, ESQ.

ROBERT N. FORD, ESQ.

JORDAN A. LUKE, ESQ.

Office of the United States Attorney

United States Courthouse

Washington, D.C.

DATED:

11

BNA's Daily Reporter System

DAILY LABOR REPORT

CU RREN T

DEVELOPM ENTS

SECTION

(No. 93) A - 1

1 atice d e p a r t m e n t r e t r a c t s its p o l ic y of

OPPOSING ATTORNEYS' FEES IN TITLE VII CASES

The Justice Department is dropping its policy of opposing attorneys' fee awards to

su ccessfu l plaintiffs in cases brought under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 against

federal agencies.

The switch in position is disclosed in a letter to Senator John V. Tunney (D-Cal)

•v.im Acting Assistant Attorney General Irving Jaffe, in which he states:

"I have concluded that the position [of opposing attorneys’ fees) should be abandoned.

The U S Attorneys will therefore be instructed not to assert that position in any case

properly brought under the 1972 amendments and to withdraw the position from any such

cases now pending. ”

Tunney, chairman of the Subcommittee on Constitutional Rights of the Judiciary Com

mittee had written to the Justice Department on March 17, maintaining that opposing attorney

/‘ee aWard3 in Title VII cases, "seems to fly in the face of congressional intent, and may well

frustrate the effectiveness of Title .VII. "

Tunney’ s Subcommittee on Representation of Citizen Interests, now merged with thê

C onstitutional Rights Subcommittee, held two days of hearings on court awards of attorneys

fees in October 1973. From these hearings, Tunney said he learned that awards of reason

,bie attorneys’ fees in Title VII suits are essential to assure that government employees will

re able to obtain legal representation in discrimination cases. He ad e .

"In the three years since the 1972 amendments took effect, hundreds of discrimination

cases have been filed against federal agencies. Many are still pending, and this change

of policy potentially affects all of them. "

The government had taken the position opposing the award of attorneys' fees on the

grounds that such an award was not specifically provided for by the 1972 amendments to the

Act. Jaffe's May 6 letter explaining the policy change follows: ( IEa i )

This is in response to your letter of April 4, 1975 and in further response to your

Setter of March 17, 1975. I regret and apologize for my delay in replying.

You correctly state that the Government has taken a position in opposing the award of

attorneys' fees on the theory that such an award was not specifically provided for by the 9

amendments to Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. That position was asserted in •

Hammond v. Balzano to which you referred in your March 17th letter and in Palmer v. Rogers^

to which you referred in your April 4th letter, and in other cases as well.

In resDonse to your inquiry, I instituted a staff review of this position and having care

fully considered and evaluated the results of that review, I have concluded that the position

should be abandoned. The United States Attorneys will therefore be instructed not to assert

‘hat oosition in any case properly brought under the 1972 amendments and to withdraw the

position from any such cases now pending. We shall, of course, continue to address oursel

to appropriate issues relating to the reasonableness of amounts so requested and to the court s

discretion in making an award.

Published by THE BUREAU OF N ATION AL A FF A IR S, INC., WASHINGTON, D .C . 20037

R i g h t o f r e p r o d u c t i o n and r e d i s t r i b u t i o n r e s e r v e d

A - 2 (No. 93) CURRENT DEVELOPMENTS (DLR) 5-13-75

The abandonment of our position with respect to attorneys’ fees does not mean that

I consider the former position to have been frivolously asserted. It does have an arguable

basis. Under existing law as set forth in 28 U. S.C. §2412, attorneys' fees may not be

awarded against the United States or any agency or official of the United States unless

specifically provided by statute. The statute which the law requires must be specific since the

sovereign's consent to have attorneys' fees awarded against it cannot be implied but must be

unequivocally expressed. See United States v. King, 395 U. S. 1, 4; Affiliated Ute Citizens

v. United States, 406 U. S. 128, 142. A waiver of sovereign immunity cannot be implied by

construction of an ambiguous statute. Petterway v. Veterans Administration Hospital, 495

F. 2d 1223, 1225, n. 3 (5th C ir ., 1974). . V

The statute enacted by the 1972 amendments upon which reliance rests for the award

of attorneys' fees, 42 U.S.C. §2000e-16 (d), is arguably ambiguous. It provides that the ..

"provisions of Section 2000e-5 (f) through (k) of this title, as applicable, shall govern civil

actions brought hereunder." Section 2000e-5 (k) authorizes award of attorneys' fees to the

prevailing party other than the EEOC or the United States in situations where the statute

contemplates that EEOC or the United States will be plaintiffs. On the other hand, §2000e-16

(c) mandates a civil action against the head of the department, agency or unit, not the United

States, and the department or agency head will be the defendant. The application of §2000e-5

(k) to the 1972 amendments requires inferences and implications to be drawn to confer upon

it the specificity that the law requires. •

At the same time, however, I recognize that unless such clearly intended inferences-

be drawn, the inclusion of subsection 5 (k) within the ambit of §2000e-16 (d), might render :

such inclusion without purpose or effect. These considerations have weighed heavily in my

decision.

(signed) IRVING JAFFE

Acting Assistant Attorney

General

- 0 -

PROGRESS IN PREPAID LEGAL

SERVICES: "SLOW, BUT SURE"

Even with the ethical problems presented by prepaid legal services apparently now

well in hand, the development of prepaid legal systems on a scale akin to those in the health

care industry is still in the distant future. The primary obstacle, as identified by participants

in the American Bar Association's Fifth National Conference on Prepaid Legal Services in

New Orleans last week, is the lack of consumer awareness. Prepaid legal services also must

surmount problems arising in the following areas - - state insurance regulation, quality and

cost control, the effect of ERISA, the antitrust laws, and tax consequences.

The conference identified three primary types of prepaid plans - - those sponsored

by bar associations; those operated through insurance companies; and those funded by various

groups such as unions, co-ops and credit unions. The first two suffer the most from lack of

consumer awareness, since these'programs depend upon some type of marketing. Group 7

funded systems, on the other hand, are "top down" types of operations--participation in them

is guaranteed by the sponsoring group. The first two types were generally described as

floundering, as being something for the future, perhaps in "five years."

Henry A. Politz, of Shreveport, L a ., initiated the roll call by moderating the panel on

bar association plans. The first such plan, operated by the Ohio Legal Services Fund (OLS) in

Columbus, was described through written remarks submitted by Jay B. Ellis.

Published by THE BUREAU OF N AT ION AL A F F A IR S, INC., WASHINGTON, D .C . 20037

R ig h t o f r e p r o d u c t i o n a n d r e d i s t r i b u t i o n r e s e r v e d