McGautha v California Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

May 3, 1971

64 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. McGautha v California Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1971. 265f5f53-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/cff129a1-d8b6-4a6d-b80d-7fd1e63856a3/mcgautha-v-california-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

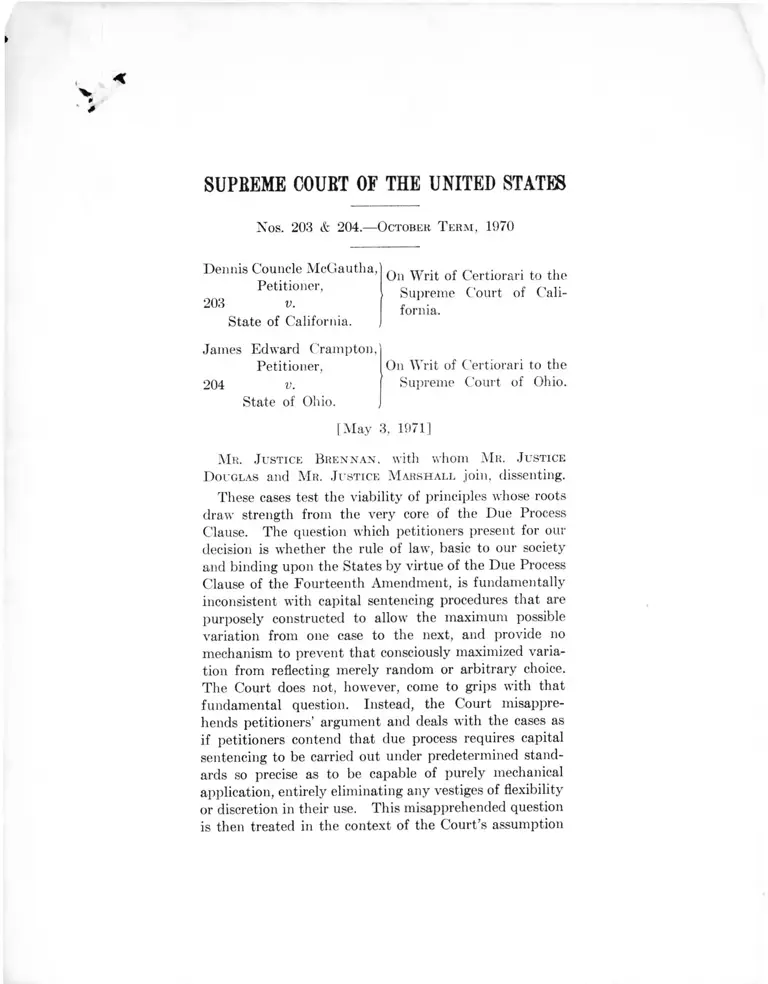

SUPBEME COUBT OF THE UNITED STATES

Nos. 203 & 204.—October T erm, 1970

Dennis Councle McGautha,

Petitioner,

On Writ of Certiorari to the

Supreme Court of Cali

fornia.203 v.

State of California.

James Edward Crampton,

Petitioner, On Writ of Certiorari to the

Supreme Court of Ohio.204 v.

State of Ohio.

[May 3, 1971]

M r. Justice Brennan , with whom M r. Justice

D ouglas and M r. Justice M arshall join, dissenting.

These cases test the viability of principles whose roots

draw strength from the very core of the Due Process

Clause. The question which petitioners present for our

decision is whether the rule of law, basic to our society

and binding upon the States by virtue of the Due Process

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, is fundamentally

inconsistent with capital sentencing procedures that are

purposely constructed to allow the maximum possible

variation from one case to the next, and provide no

mechanism to prevent that consciously maximized varia

tion from reflecting merely random or arbitrary choice.

The Court does not, however, come to grips with that

fundamental question. Instead, the Court misappre

hends petitioners’ argument and deals with the cases as

if petitioners contend that due process requires capital

sentencing to be carried out under predetermined stand

ards so precise as to be capable of purely mechanical

application, entirely eliminating any vestiges of flexibility

or discretion in their use. This misapprehended question

is then treated in the context of the Court’s assumption

203 <fc 204— DISSENT

that the legislatures of Ohio and California are incom

petent to express with clarity the bases upon which they

have determined that some persons guilty of some crimes

should be killed, while others should live— an assumption

that, significantly, finds no support in the arguments

made by those States in these cases. With the issue so

polarized, the Court is led to conclude that the rule of

law and the power of the States to kill are in irrecon

cilable conflict. This conflict the Court resolves in favor

of the States’ power to kill.

In my view the Court errs at all points from its

premises to its conclusions. Unlike the Court, I do not

believe that the legislatures of the 50 States are so devoid

of wisdom and the power of rational thought that they

are unable to face the problem of capital punishment

directly, and to determine for themselves the criteria

under which convicted capital felons should be chosen to

live or die. We are thus not, in my view, faced by the

dilemma perceived by the Court, for cases in this Court

have for almost a century and a half approved a multi

plicity of imaginative procedures designed by the state

and federal legislatures to assure evenhanded treatment

and ultimate legislative control regarding matters which

the legislatures have deemed either too complex or other

wise inapposite for regulation under predetermined rules

capable of automatic application in every case. Finally,

even if I shared the Court’s view that the rule of law

and the power of the States to kill are in irreconcilable

conflict, I would have no hesitation in concluding that

the rule of law must prevail.

Except where it incorporates specific substantive con

stitutional guarantees against state infringement, the

Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment does

not limit the power of the States to choose among com

peting social and economic theories in the ordering of life

within their respective jurisdictions. But it does require

2 McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA

203 & 204—DISSENT

that, if state power is to be exerted, these choices must

be made by a responsible organ of state government.

For if they are not, the very best that may be hoped for

is that state power will be exercised not upon the basis

of any social choice made by the people of the State,

but instead merely on the basis of social choices made

at the whim of the particular state official wielding the

power. If there is no effective supervision of this process

to insure consistency of decision, it can amount to nothing

more than government by whim. But ours has been

“termed a government of laws, not of men.” Marbury v.

Madison, 1 Cranch 137, 1G3 (1803). Government by

whim is the very antithesis of due process.

It is not a mere historical accident that “ [t]he history

of liberty has largely been the history of observance

of procedural safeguards.” McNabb v. United States,

318 U. S. 332, 347 (1943) (Frankfurter, J.). The range

of permissible state choice among competing social and

economic theories is so broad that almost any arbitrary

or otherwise impermissible discrimination among individ

uals may mask itself as nothing more than such a per

missible exercise of choice unless procedures are devised

which adequately insure that the relevant choice is

actually made. Such procedures may take a variety of

forms. The decisionmaker may be provided with a set

of guidelines to apply in rendering judgment. His deci

sion may be required to rest upon the presence or absence

of specific factors. If the legislature concludes that the

range of variation to be dealt with precludes adequate

treatment under inflexible, predetermined standards it

may adopt more imaginative procedures. The specificity

of standards may be relaxed, directing the decisionmaker’s

attention to the basic policy determinations underlying

the statute without binding his action with regard to

matters of important but unforeseen detail. He may be

instructed to consider a list of factors—either illustrative

-MoGAUTHA v . CALIFORNIA 3

203 & 204—DISSENT

or exhaustive—intended to illuminate the question pre

sented without setting a fixed balance. The process may

draw upon the genius of the common law, and direct

itself towards the refinement of understanding through

case-by-case development. In sucli cases decision may

be left almost entirely in the hands of the body to which

it is delegated, with ultimate legislative supervision on

questions of basic policy afforded by requiring the deci

sionmakers to explain their actions, and evenhanded treat

ment enhanced by requiring disputed factual issues to be

resolved and providing for some form of subsequent re

view. Creative legislatures may devise yet other proce

dures. Depending upon the nature and importance of

the issues to be decided, the kind of tribunal rendering

judgment, the number and frequency of decisions to be

made, and the number of separate tribunals involved in

the process, these techniques may be applied singly or in

combination.

It is of critical importance in the present cases to

emphasize that we are not called upon to determine the

adequacy or inadequacy of any particular legislative pro

cedure designed to give rationality to the capital sen

tencing process. For the plain fact is that the legisla

tures of California and Ohio, whence come these cases,

have sought no solution at all. We are not presented

with a State’s attempt to provide standards, attacked as

impermissible or inadequate. We are not presented with

a legislative attempt to draw wisdom from experience

through a process looking towards growth in understand

ing through the accumulation of a variety of experiences.

We are not presented with the slightest attempt to bring

the power of reason to bear on the considerations rele

vant to capital sentencing. We are faced with nothing

more than stark legislative abdication. Not once in the

history of this Court, until today, have we sustained

against a due process challenge such an unguided, un

4 McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA

203 & 204— DISSENT

bridled, unreviewable exercise of naked power. Almost

a century ago, we found an almost identical California

procedure constitutionally inadequate to license a laun

dry. Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356, 366-367, 369-

370 ( 1SS6). Today we hold it adequate to license a life.

I would reverse petitioners’ sentences of death.

I

“Our system of ordered liberty is based, like the com

mon law, on enlightened and uniformly applied legal

principle, not on ad hoc notions of what is right or wrong

in a particular case.” Harlan, Thoughts at a Dedica

tion, in The Evolution of a Judicial Philosophy 289, 291-

292 (D. Shapiro ed. 1969).1 The dangers inherent in any

grant of governmental power without procedural safe

guards upon its exercise were known to English law long

long before the Constitution was established. See, e. q.,

8 How. St. Tr. 55-58 n. *. The principle that our Gov

ernment shall be of laws and not of men is so strongly

woven into our constitutional fabric that it has found

recognition in not .just one but several provisions of the

Constitution.2 And this principle has been central to

McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA 5

1 Mv Brother Haiu.a x continue.-;: “ The stability and flexibility

that onr constitutional system at once possesses is largely due to

our having carried over into constitutional adjudication the common-

law approach to legal d e v e lo p m e n t Id.. at 292.

2 The prohibition against bills of attainder. Article I, §9 , cl. 3

(federal), §10. cl. 1 (state), protects individuals or groups against

being singled out for legislative instead of judicial trial. See United

States v. Brown, 3,si U. S. 437, 442-446 (1965); id., at 462 (dissent);

Cummings v. Missouri, 4 Wall. 277, 322-325 (1S67). The prohibi

tion against ex post facto laws, joined in the Constitution to the ban

on bills of attainder, prevents legislatures from achieving similar ends

by indirection, either by making criminal acts that were innocent

when performed, Cummings v. Missouri, supra, at 325-326; Colder

v. Bxdl, 3 Dali. 386, 390 (1798) (Chase, ,T.), or by increasing the

punishment imposed upon admittedly criminal acts that have al

203 & 204—DISSENT

the decisions of this Court giving content to the Due

Process Clause.8 As we said in Hurtado v. California,

110 U. S. 516, 535-536 (1884):

“ [I ]t is not to be supposed that . . . the amend

ment prescribing due process of law is too vague and 3

G McGAlJTHA v. CALIFORNIA

ready been committed. In re Medley, 134 U. S. 160, 166-173

(1800); Colder v. Bull, supra. The constitutional limitation of

federal legislative power to the Congress has been applied to require

that fundamental policy choices be made not by private individuals—

or even public officers—acting pursuant to an unguided and un-

supervised delegation of legislative authority, but by the Nation as

a whole acting through Congress. See, e. g., FCC v. RCA Com

munications. Inc.., 346 U. S. 86. 90 (1953); Lie,liter v. United States,

334 IT. S. 742. 766, 769-773, 778 (1948); Schechter Poultry Corp. v.

United States, 295 U. S. 495, 529-530, 537-539 (1935); Panama

R ef’g Co. v. Ryan, 293 U. S. 388, 414-430 (1935); id., at 434, 435

(Cardozo, J., dissenting). Finally, the requirement of evenhanded

treatment imposed upon the States and their agents by the Equal

Protection Clause, see Cooper v. Aaron, 35S U. S. 1, 16-17 (1958),

McFarland v. American Sugar Co., 241 U. S. 79, 86-87 (1916)

(Holmes, ,T.), has been applied to the Federal Government as well

through the Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause. E. g., Shapiro

v. Thompson, 394 U. S. 618, 641-642 (1969); Schneider v. Rusk,

377 U. S. 163, 168-169 (1964); Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497

(1954).

3 Thus, although recognizing that the explicit constitutional pro

hibition against ex post facto laws applies only to legislative action,

we held in Bouic v. City of Columbia, 37S U, S. 347, 353-354 (1964),

that due process was violated by like action on the part of a state

court. Significantly, the dissenting Justices in Bouie took issue

only with the Court’s conclusion that the interpretation of the

statute in question by the State Supreme Court was not foreshadowed

by prior state law. See id., at 366-367. Similarly, although we have

held the States not bound, as is the Federal Government, by the

doctrine of separation of powers, Dreyer v. Illinois, 1S7 U. S. 71, 83-

84 (1902); Sweezy v. New Hampshire, 354 U. S. 234, 255 (1957),

we have nevertheless held that state delegation of legislative authority

without guideline or check violates due process. Seattle Trust Co.

v. Roberge, 278 U. S. 116, 120-122 (1928); Eubank v. Richmond,

203 & 204— DISSENT

indefinite to operate as a practical restraint. . . .

Law is something more than mere will asserted as

an act of power. It must be not a special rule for

a particular person or a particular case, but . . . ‘the

general law . . .’ so ‘that every citizen shall hold

his life, liberty, property and immunities under the

protection of the general rules which govern society,'

and thus excluding, as not due process of law, acts

of attainder, bills of pains and penalties, acts of con

fiscation . . . and other similar special, partial and

arbitrary exertions of power under the forms of legis

lation. Arbitrary power, enforcing its edicts to the-

injury of the persons and property of its subjects,

is not law, whether manifested as the decree of a

personal monarch or of an impersonal multitude.”

The principal function of the Due Process Clause is

to insure that state power is exercised only pursuant to

procedures adequate to vindicate individual rights.4

220 U. S. 137, 143-144 (1912); of. Browning v. Hooper, 269 U. S.

396,405-406 (1926). See the discussion infra, at [24-26], Finally,,

in Hurtado v. California, 110 U. S. 516, 535-536 (1S84), quoted in

the text immediately above, we noted as an example of a clear vio

lation of due process the passage by a legislature of a bill of attainder.

Cf. n. 2, supra, and cases cited.

4 We have, of course, applied specific substantive protections of the

Bill of Rights to limit state power under the Due Process Clause.

E. g., Near v. Minnesota, 283 U. S. 697 (1931) (First Amendment);

Robinson v. California, 370 U. S. 660 (1962) (Eighth Amendment);

Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U. S. 479 , 481-4S6 (1965) (First,

Third, Fourth, Fifth, and Ninth Amendments). Conversely, we

have held at least some aspects of the Fourteenth Amendment’s

Equal Protection Clause applicable to limit federal power under the

Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment, See Shapiro v.

Thompson, 394 U. S. 618, 641-642 (1969), and cases cited. Finally,

we have of course held that due process forbids a State from punish

ing the assertion of federally guaranteed rights whether procedural

or otherwise. North Carolina v. Pearce, 395 U. S. 711, 723-725-

McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA 7

203 & 20-1— DISSENT

While we have, on rare occasions, held that clue process

requires specific procedural devices not explicitly com

manded by the Bill of Rights,* 3 * 5 * we have generally either

indicated one acceptable procedure and left the States

free to devise others," or else merely ruled upon the

validity or invalidity of a particular procedure without

attempting to limit or even guide state choice of pro

cedural mechanisms beyond stating the obvious proposi

tion that inadequate mechanisms may not be employed.7

Several principles, however, have until today been

consistently employed to guide determinations of the

adequacy of any given state procedure. “ When the Gov

ernment exacts . . . much, the importance of fair, even-

handed, and uniform decisionmaking is obviously intensi

fied.” Gillette v. United States, 40- U. S. -----, -----

(1971). Procedures adequate to determine a welfare

claim may not suffice to try a felony charge. Compare

Goldberg Kelly, 397 U. S. 254, 270-271 (1970), with

Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U. S. 335 (1963). Second,

even where the only rights to be adjudicated are those

(1900): Spevack v. Klein, 385 II. S. 511 (1907): of. Ex parte Hull,

312 U. S. 540 (1941). But wo have long rejected the view, typified

by, e. g„ Adkins v. Children’s Hospital, 201 U. S. 525 (1923). over

ruled in West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish. 300 U. S. 379 (1937),

that the Due Process Clause vests judges with a roving commission

to impose their own notions of wise social policy upon the States.

Ferguson v. Shrupa, 372 II. S. 720. 730-731 (1903).

3 E. g„ North Carolina, v. Pearce, 395 II. S. 711, 725-720 (1909);

Boykin v. Alabama, 395 I'. S. 238. 242-244 (1909); see also Goldberg

v. Kelly, 397 II. S. 254. 209-271 (1970).

« E. f/., United States v. Wade, 388 IT. S. 218, 236-239 (1907);

Miranda v. Arizona, 384 IT. S. 430, 407-473 (1900); Jackson v.

Denno, 378 U. S. 368, 377-391 (1904).

7 Fj. g., Johnson v. Avery, 393 LI. S. 483 , 488-490 (1909); In re

Murchison, 349 II. S. 133 (1955): Seattle Trust Co. v. Roberge,

278 U.S. 110 (1928).

8 MeGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA

203 & 204— DISSENT

created and protected by state law, due process requires

that state procedures be adequate to allow all those con

cerned a fair hearing of their state-law claims. Boddie v.

Connecticut, 40- U. S. ----- (1971); Covey v. Town of

Somers, 351 U. S. 141 (1956); Mullane v. Central Han

over Trust Co., 339 U. S. 306 (1950). Third, where fed

erally protected rights are involved, due process com

mands not only that state procedure be adequate to

assure a fair hearing of federal claims, In re Gault, 387

U. S. 1 (1967), but also that it provide adequate oppor

tunity for review of those federal claims where such

review is otherwise available. Goldberg v. Kelly, 397

U. S., at 271; Boykin v. Alabama, 395 U. S. 238, 242-244

(1969); Jackson v. Denno, 378 U. S. 368, 387 (1964); cf.

North Carolina v. Pearce, 395 U. S. 711, 725-726 (1969);

In re Murchison, 349 U. S. 133, 136 (1955). Finally, and

closely related to the previous point, due process requires

that procedures for the exercise of state power be struc

tured in such a way that, ultimately at least, fundamental

choices among competing state policies are resolved by

a responsible organ of state government. Louisiana v.

United States, 380 I'. S. 145, 152-153 (1965) ( Black, J.) ;

FCC v. RCA Communications, Inc., 346 U. S. 86. 90

(1953); Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U. S. 268 (1951);

United States v. Rock Royal Co-op, 307 U. S. 533, 574,

575 (1939); Currin v. Wallace, 30(5 U. S. 1, 15 (1939);

Lovell v. Griffin, 303 U. S. 444 (1938); Browning v.

Hooper, 269 U. S. 396. 405-406 (1926); McKinley v.

United States, 249 U. S. 397, 399 (1919); Eubank v.

Richmond, 226 IT. S. 137, 143-144 (1912); Yick Wo v.

Hopkins, 11S U. S. 356, 366-367, 369-370 (1886). The

damage that today’s holding, if followed, would do to our

constitutional fabric can only be understood from a closer

examination of our cases than is contained in the Court’s

opinion. I therefore turn to those cases.

McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA 0

203 & 204—DISSENT

10 McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA

A

Analysis may usefully begin with this Court’s cases

applying what has come to be known as the “void-for-

vagueness” doctrine. It is sometimes suggested that in

holding a statute void for vagueness, this Court is merely

applying one of two separate doctrines: first, that a crim

inal statute must give fair notice of the conduct that it

forbids, e. g., Lanzetta v. New Jersey, 306 U. S. 451

(1939); Connolly v. General Construction Co., 269 U. S.

385, 391 (1926); and second, that a statute may not

constitutionally be enforced if it indiscriminately sweeps

within its ambit conduct that may not be the subject

of criminal sanctions as well as conduct that may. E. g.,

Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 U. S. 360 (1964); Dombroivski v.

Pfister, 380 U. S. 479, 492-496 (1965). To this is often

added the observation that both doctrines apply with

particular vigor to state regulation of conduct at or

near the boundaries of the First Amendment. See

United States v. National Dairy Corp., 372 U. S. 29, 36

(1963); Smith v. California, 361 U. S. 147, 150-152

(1959).8 But unless it be assumed that our decisions in

such matters have shown an almost unparellelled incon

sistency, these factors may not be taken as more than a

partial explanation of the doctrine.

To begin with, we have never treated claims of uncon

stitutional statutory vagueness in terms of the statute

as written or as construed prior to the time of the conduct

in question. Instead, we have invariably dealt with the

statute as glossed by the courts below at the time of

decision here. E. g., Giaccio v. Pennsylvania, 382 U. S.

399 (1966); Winters v. New York, 333 U. S. 507 (1948);

8 For analysis in substantially these terms, see, e. g., Collings,

Unconstitutional Uncertainty— An Appraisal, 40 Cornell L. Q. 195

(1955); Freund. The Supremo Court and Civil Liberties, 4 Vand.

L. Rev. 533 (1951); Comment, 53 Mich. L. Rev. 264 (1954).

203 & 204—DISSENT

Cox v. New Hampshire, 312 U. S. 569 (1941). In Musser

v. Utah, 333 U. S. 95 (1948), we even remanded a crim

inal case to the Utah Supreme Court for a construction

of the statute so that its possible vagueness could be

analyzed. In dealing with vagueness attacks on federal

statutes, we have not hesitated to construe the statute

to avoid vagueness problems and, having so construed it,

apply it to the case at hand. See United States v.

Vuitcli, ---- U. S. ----- (1971); Dennis v. United States,

341 U. S. 494, 502 (1951); Kay v. United States, 303

U. S. 1 (1938). If the vagueness doctrine were funda

mentally premised upon a concept of fair notice, such

treatment would simply make no sense: a citizen can

not be expected to foresee subsequent construction of

a statute by this or any other court. See Freund, The

Supreme Court and Civil Liberties, 4 Vand. L. Rev.

533, 540-542 (1951). But if, as I believe, the doctrine

of vagueness is premised upon the fundamental notion

that due process requires governments to make explicit

their choices among competing social policies, see pp.

112-18] infra, the inconsistency between theory and

practice disappears. Of course such a choice, once made,

is not irrevocable: statutes may be amended and statu

tory construction overruled. Nevertheless, an explicit

state choice among possible statutory constructions sub

stantially reduces the likelihood that subsequent convic

tions under the statute will be based on impermissible

factors.9 It also renders more effective the available

9 A vague statute may be applied one way to one person and a

different way to another. Aside from the fact that this in itself

would constitute a denial of equal protection, Nicrnotko v. Maryland,

340 U. S. 268, 272 (1951), cf. H. Black, A Constitutional'Faith

31-32 (1969), the reasons underlying different application to dif

ferent individuals may in themselves be constitutionally imper

missible. Cf. Schacht v. United States, 398 U. S. 58 (1970) (appli

cability of statute determined by political views); Yick Wo v.

Hopkins, 118 I . S. 356 (1886) (application of statute on racial basis).

McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA 11

203 & 204—DISSENT

mechanisms for judicial review, by increasing the likeli

hood that impermissible factors, if relied upon, will be

discernible from the record. Thus in Thompson v. Louis

ville, 302 U. S. 199 (1960), we were faced with the appli

cation of a specific vagrancy statute to conduct—dancing

in a public bar— that there is no reason to believe could

not have been constitutionally prohibited had the State

chosen to do so. We were, however, able to examine the

record and conclude that there was in fact no evidence

that could support a conviction under the statute. Cf.

Bachellar v. Maryland, 397 1'. S. 564 (1970) (impossible

to determine whether verdict rested upon permissible

or impermissible grounds).

Second, in dealing with statutes that are unconstitu

tionally overbroad, we have consistently indicated that

“once an acceptable limiting construction is obtained,

[such a statute] may be applied to conduct occurring

prior to the construction, provided such application af

fords fair warning to the defendants.” Dombrowski v..

Pfister, 380 IT. S. 479. 491 n. 7 (1965) (citations omit

ted ) ; in see. e. </., Poulos v. Xew Hampshire, 345 U. S. 395

(1953). That is, an unconstitutionally overbroad stat

ute may not be enforced at all until an acceptable con

struction has been obtained, e. g., Thornhill v. Alabamar

310 U. S. 88 (1940); but once such a construction has

been made, the statute as construed may be applied to

conduct occurring prior to the limiting construction. If

notice and overbreadth were the only components of the

vagueness doctrine, this treatment would, once again, be

inexplicable. So far as notice is concerned, one who has

engaged in certain conduct prior to the limiting construc

tion of an overbroad statute has obviously not received

from that construction any warning that would have en- *

12 McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA

Younger v. Harris, 40- U. S. ---- (1971), and its companions

cast no shadow upon the sentence quoted.

203 & 204— DISSENT

abled him to keep his conduct within the bounds of law.

Similarly, if adequate notice has in fact been given by an

overbroad statute that certain conduct was criminally

punishable, it is hard to see how the doctrine of over-

breadth is furthered by forbidding the State, on the one

hand, to punish that conduct so long as an acceptable

limiting construction lias not been obtained, but permit

ting it to punish the same, prior conduct once the statute

has been acceptably construed. Once again, however, our

actions are not at all inexplicable if examined in the terms

articulated here. Once an acceptable limiting construc

tion has in fact been obtained, there is by that very fact

an assurance that a responsible organ of state power has

made an explicit choice among possible alternative poli

cies: for it should not be forgotten that the States possess

constitutional power to make criminal much conduct that

they may not wish to forbid, or may even desire to en

courage. It a vague or overbroad statute is applied be

fore it has been acceptably construed, there remains the

danger that an individual whose conduct is admittedly

clearly within the scope of the statute on its face will be

punished for actions which in fact the State does not

desire to make generally punishible— conduct which, if

engaged in by another person, would not be subject to

criminal liability. Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham, 382

l . S. 87, 91-92 (1965). Allowing a vague or overbroad

statute to be enforced if. and only if, an acceptable con

struction has been obtained forces the State to make

explicit its social choices and prevents discrimination

through the application of one policy to one person and

another policy to others.” 11

McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA 13

11 A closely related proposition may be derived from a separate line

of cases. In Louisiana Power A Light Co. v. City of Thibodaux,

300 U. S. 25 (1959), we upheld abstention by a federal district

court in a diversity action from decision whether, under a state

statute never construed by the Louisiana courts, cities in the State

20.3 & 204— DISSENT

Particularly relevant to the present case is our decision

in Giaccio v. Pennsylvania, 382 U. S. 399 (1966). That

case involved a statute whereby Pennsylvania attempted

to mitigate the harshness of its common-law rule requir

ing criminal defendants to pay the costs of prosecution

in all cases 12 by committing the matter to the discretion

possessed the power to take local gas and electric companies by

eminent domain. The same day, in Allegheny County v. Frank

Mashuda Co., 360 11. S. 185 (1959), we upheld the action of another

district court in refusing to abstain from decision whether, under

state law allowing takings for public but not for private use, Alle

gheny County possessed the power to take a particular property for

a particular use. Are the decisions irreconcilable? As we have often

remarked, the basis of diversity jurisdiction is “ the supposition that,

possibly, the state tribunals] might not be impartial between their

own citizens and foreigners.” Pease v. Peck, 18 How. 595, 599

(1856). The question of state law presented in Thibodaux was a

broad one having substantial ramifications beyond the lawsuit at

hand. Any prejudice against the out-of-state company involved

in that case could have been given effect in state courts only at the

cost of a possibly incorrect decision that would have significant

adverse effect upon state citizens as well as the particular outsider

involved in the suit. In Mashuda, on the other hand, decision one

way or another would have little or no effect beyond the case in

question: any possible state bias against out-of-staters could be given

full effect without hampering any significant state policy. Taken

together, then, Thibodaux and Mashuda may stand for the propo

sition that the possibility of bias which stands at the foundation of

federal diversity jurisdiction may nevertheless be discounted if that

bias could be given effect only through a decision that will have

inevitable repercussions on a matter of fundamental state policy.

Put another way, Thibodaux and Mashuda may serve to illustrate

in another context the principle that necessarily underlies many of

this Court’s “ vagueness” decisions: the due process requirement that

States make explicit their choice among competing views on ques

tions of fundamental state policy serves to enforce the requirement of

evenhanded treatment that due process commands.

12 See Brief for Respondent in Giaccio, at 8-10; Commonwealth v.

Tilghman, 4 S. & R. 127 (Pa. Sup. Ct. 1818); Act of March 20, 1797,

3 Smith’s Law's 281.

14 McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA

203 & 204— DISSENT

of the jury in cases where the defendant was found not

guilty.'" Two members of this Court, concurring in the

result, would have held that due process forbade the

imposition of costs upon an acquitted defendant. 382

U. S., at 405. We refused, however, to base our decision

on that ground. In an opinion by my Brother Black,

we said:

“We agree with the trial court . . . that the 1860

Act is invalid under the Due Process Clause because

of vagueness and the absence of any standards suffi

cient to enable defendants to protect themselves

against arbitrary and discriminatory impositions of

costs.

. . . It is established that a law fails to meet

the requirements of the Due Process Clause if it is

so vague and standardless that it leaves the public

uncertain as to the conduct it prohibits or leaves

judges and jurors free to decide, without any legally

fixed standards, what is prohibited and what is not

in each particular case. This 1860 Pennsylvania Act

contains no standards at all . . . . Certainly one

of the basic purposes of the Due Process Clause has

always been to protect a person against having the

Government impose burdens upon him except in

accordance with the valid laws of the land. Implicit

in this constitutional safeguard is the premise that

the law must be one that carries an understandable

meaning ivith legal standards that courts must

enforce. . . .

. . The State contends that . . . state court

interpretations have provided standards and guides 13

13 Some standards were provided to guide the jury’s decision. See

382 U. S., at 403-404. See App. 30-32 in Giaccio for the charge

given in that case.

McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA 15.

203 & 204—DISSENT

that cure the . . . constitutional deficiencies. We do

not agree. . . . In this case the trial judge in

structed the jury that it might place the costs of

prosecution on the appellant, though found not

guilty of the crime charged, if the jury found that

‘he had been guilty of some misconduct less than

the offense which is charged but nevertheless miscon

duct of some kind as a result of which he should be

required to pay some penalty short of conviction

[and] . . . his misconduct has given rise to the

prosecution.’

“ It may possibly be that the trial court’s charge

comes nearer to giving a guide to the jury than those

that preceded it, but it still falls short of the kind

of legal standard due process requires. . . .” 382

U. S., at 402-404 (emphasis supplied) (citations

omitted).”

Several features of Giaccio are especially pertinent in

the present context. First, there were no First Amend

ment implications in either the conduct charged or that

in which Giaccio claimed to have engaged: the State’s

evidence was to the effect that Giaccio had wantonly dis

charged a firearm at another, in violation of Pa. Stat.

Ann., Tit. 19, § 1222 (1963), and Giaccio’s defense was

that “ the firearm he had discharged was a starter pistol

which only fired blanks.” 382 U. S., at 400. Second, we

were not presented with a defendant who had been con

victed for conduct he could not have known was unlawful.

Whether or not Giaccio’s actions fell within § 1222, his

16 McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA

” We did in Giaccio .say that “ we intend to cast no doubt whatever

on the constitutionality of the settled practice of many States”-

prescribing jury sentencing. 382 U. S., at 403 n. 8. Insofar as

jury sentencing in general is concerned, Giaccio is by no means

necessarily inconsistent with the practice. See infra, pp. [63-64].

203 & 204—DISSENT

conduct was unquestionably punishable under other state

laws. E. g., Pa. Stat. Ann., Tit. 19, §4406 (1963). Fi

nally, it is worthy of note that in Giaccio two members

of this Court explicitly sought to base the result upon the

ground that, as a matter of substantive due process, the

States were forbidden to impose the costs of prosecution

upon an acquitted defendant. 382 U. S., at 40o (con

curring opinions of Stewart and Fortas, JJ.). Yet we

refused to place decision on any such ground. We held

instead, consistently with our prior decisions, that the

procedure for determining Giaccio’s punishment lacked

the safeguards against arbitrary action that are required

by due process of law.15

Our decisions applying the Due Process Clause through

the doctrine of unconstitutional vagueness, then, lead to

the following conclusions. First, the protection against

arbitrary and discriminatory action embodied in the Due

Process Clause requires that state power be exerted only

lr'I find little short of bewildering the Court’s treatment o f

Giaccio. The Court appears to read that case as standing for the

proposition that duo process forbids a jury to impose punishment

upon defendants for conduct which, “ although not amounting to the

crime upon which they were charged, was nevertheless found to be

‘reprehensible.’ ” Ante, at 24 n. 18. Of course the procedures under

review permit precisely the same action, without providing even the

minimal safeguards found insufficient in Giaccio. See Part III, infra.

If there is a difference between Giaccio and the present cases, it is that

the procedures now under review apply not to acquitted defendants,

but only to those who have already been found guilty of some crime.

But the Court elsewhere in its opinion has concluded that the “ rele

vant differences between sentencing and determination of guilt or

innocence are not so great as to call for a difference in constitutional

result.” Ante, at [33]. I think it is fair to say that nowhere in

its treatment of Giaccio does the Court even attempt to explain why

the unspecified “ relevant differences” that it finds do call for “a

difference in constitutional result.”

McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA 17

203 & 204— DISSENT

through mechanisms which assure that fundamental

choices among competing state policies be explicitly made

by some responsible organ of the State.1" Second, the

cases suggest that due process requires as well that state

procedures for decision of questions that may have ad

verse consequences for an individual neither leave room

for the deprivation sub silentio of the individual’s fed

erally protected rights nor unduly frustrate the federal

judicial review provided for the vindication of those

rights. This second point is explicitly made in a not

unrelated line of cases, to which I now turn.

B

Whether through its own force or only through the

application of other, specific constitutional guarantees,

the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment

protects individuals from a narrow class of impermissible

exertions of power by the States. As applied to the

1,1 This same point may be made another way. We have con

sistently held that the Due Process Clause protects individuals

against arbitrary governmental action. Despite sharp conflict among

the members of this Court over the standards to be applied in de

termining whether governmental action is in fact “ arbitrary,” see,

e. g., Grisicold v. Connecticut, 381 U. S. 479, 499 (1965) (Harlan,

J., concurring); Id., at 507 (Black, J„ dissenting), all members of

this Court have agreed that the phrase has some content. E. g.,

Giaccio v. Pennsylvania, 382 U. S. 399, 402 (1966) (Black, J.)

(due process requires defendants to be protected “against arbitrary

and discriminatory” punishment). Our vagueness cases suggest that

state action is arbitrary and therefore violative of due process not

only if it is (a) based upon distinctions which the State is specifically

forbidden to make, e. g.. Loving v. Virginia, 388 U. S. 1, 12 (1967);

or (b) designed to, or has the effect of, punishing an individual for

the assertion of federally protected rights, e. g., North Carolina v.

Pearce, 395 U. S. 711, 723-725 (1969): id., at 739 (Black, J.), but

also if it is (c) based upon a permissible state policy choice which

could be but has never been explicitly made by any responsible organ

of the State.

IS McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA

203 & 204—DISSENT

procedures whereby admittedly permissible state power

is exerted, however, the Due Process Clause has consist

ently been given a wider scope. “ [0]ur system of law

has always endeavored to prevent even the probability

of unfairness.” In re Murchison, 349 U. S. 133, 136

(1955). Thus we have never suggested that every judge

who has been the target of contemptuous, personal attacks

by litigants or their attorneys is incapable of rendering

a fair decision on the merits of a contempt charge against

such persons; but we have consistently held that, except

ing only cases of urgent necessity, due process requires

that contempt charges in such cases be heard by a dif

ferent judge. Mayberry v. Pennsylvania, 400 U. S. 455

(1971); In re Murchison, supra. And in Tumey v. Ohio,

273 U. S. 510 (1927), we did not suggest that every

judgment rendered by an official who had a financial

stake in the outcome was ipso facto the product of bias.

Proceeding from a directly contrary assumption,17 we

nevertheless held that due process was violated by any

“ procedure which would offer a possible temptation to

the average man . . . not to hold the balance nice, clear

and true between the State and the accused.” Id., at

532. In Jackson v. Denno, 378 U. S. 368 (1964), one

of the two grounds on which we struck down a New

York procedure that required a jury to determine the

voluntariness of a confession at the same time that it

determined his guilt of the crime charged was that the

procedure created an impermissible—and virtually unre-

viewable—risk that the jury would not be able to dis

regard a confession that it felt was both involuntary and

true. Id., at 388-391. Similarly, in a long line of cases

beginning with Lovell v. Griffin, 303 U. S. 444 (1938),

McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA IT

17 “ There are doubtless mayors who would not allow such a con

sideration as $12 costs in each case to affect their judgment in

it . . . .” 273 IT. S , at 532.

203 & 204—DISSENT

we liavc repeatedly held that due process is violated by

state procedures for the administration of permit systems

regulating the public exercise of First Amendment rights

if the procedure allows a permit to be denied for imper

missible reasons, whether or not an individual can ac

tually demonstrate that he was denied a permit for

activity which the State could not lawfully prohibit.

And only recently, in Louisiana v. United States, 380

U. S. 145 (1965), we were faced with a state procedure

for determining voting qualifications which, in the State’s

own words, vested “discretion in the registrars of voters

to determine the qualifications of applicants for registra

tion,” but imposed “no definite and objective standards

upon registrars of voters for the administration of the

interpretation test.” Id., at 152. After quoting, with

apparent approval, an 1898 state criticism of a similar

procedure on the ground that the “arbitrary power,

lodged with the registration officer, practically places his

decision beyond the pale of judicial review,” ibid., we

noted and accepted the District Court’s finding that

“ Louisiana . . . provides no effective method whereby

arbitrary and capricious action by registrars of voters

may be prevented or redressed.” Ibid. We continued:

“The applicant facing a registrar in Louisiana thus

has been compelled to leave his voting fate to that

official’s uncontrolled power to determine whether

the applicant’s understanding of the Federal or State

Constitution is satisfactory. . . . The cherished

right of people in a country like ours to vote cannot

be obliterated by the use of laws like this, which

leave the voting fate of a citizen to the passing whim

or impulse of an individual registrar. Many of our

cases have pointed out the invalidity of laws so

completely devoid of standards and restraints.” 380

U. S„ at 152-153.

20 McCAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA

203 & 204—DISSENT

On that basis we held the Louisiana procedure for deter

mining the qualifications of prospective voters to be a

denial of due process. Ibid.is

Diverse as they are, these cases rest upon common

ground. They all stand ineluctably for the proposition

that due process requires more of the States than that

they not exert state power in impermissible ways. Spe

cifically, the rule of these cases is that state procedures

are inadequate under the Due Process Clause unless they

are designed to control arbitrary action and also to make

meaningful the otherwise available mechanism for judi

cial review. We have elsewhere made this last point

explicit. In Specht v. Patterson, 386 U. S. 606 (1967),

we held that due process in commitment proceedings,

“whether denominated civil or criminal,” id., at 608,

requires “ findings adequate to make meaningful any ap

peal that is allowed.” Id., at 610; see Garner v. Louisi

ana, 368 U. S. 157. 173 (1061). And in Jackson v. Denno,

supra, the alternative ground on which we struck down

a New York procedure for determining the voluntariness

of a confession by submitting that question to the jury

at the same time as the question of guilt was that the

“admixture of reliability and voluntariness in the con

siderations of the jury would itself entitle a defendant

to further proceedings in any case in which the essential

facts are disputed, for we cannot determine how the jury

resolved these issues and will not, assume that they were

reliably and properly resolved against the accused.” 378

U. S., at 387 (emphasis added). In other words, due

process forbids the States from adopting procedures that

would defeat the institution of federal judicial review.10 18

18 We held, as an alternative ground, that the Louisiana procedure

as applied had violated the Fifteenth Amendment. 3S0 U. 8., at

152-153.

1!> See also 378 V. 8.. at 392: “ If this ease were here upon direct

review of Jackson's conviction, we could not proceed with review

McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA 21

203 & 204— DISSENT

The depth to which these principles are embedded in

the concept of due process is evidenced by the fact that

we have, on occasion, applied them not merely to rule

that a particular state procedure is or is not permissible

under the Due Process Clause, but that a particular,

specific procedure is required by due process. We have

repeatedly held, for example, that a guilty plea and its

inevitably attendant waivers of federally guaranteed

rights are valid only if they represent a voluntary and

intelligent choice” on the part of the defendant. A orth

Carolina v. Alford, 400 U. S. 25, 31 (1970). The validity

of a guilty plea may be tested on federal habeas corpus,

where facts outside the record may be pleaded and

proved. Waley v. Johnston, 310 U. S. 101 (1942). While

recognizing the existence of such a remedy, \\e held in

Boykin v. Alabama, 395 U. S. 238 (1969), that due

process requires a record “ adequate for any review that

may be later sought,” id., at 244, and does not permit

protection of the federally guaranteed rights to be rele

gated to “ collateral proceedings that seek to probe murky

memories.” Ibid. Accordingly, we held that due process

requires a State, in accepting a plea of guilty, to make a

contemporaneous record adequate “ to show that [the

defendant! had intelligently and knowingly pleaded

guilty.” Id., at 241. And only last Term, in Goldberg

v. Kelly, 397 V. S. 254 (1970), we held that because a

decision on the withdrawal of welfare benefits must “rest

solely on the legal rules and evidence adduced at the

hearing,” id., at 271. due process requires that the decision

maker “demonstrate compliance with this elementary

requirement” by “stat[ing| the reasons for his determi

nation and indicat [ing] the evidence he relied on.” Ibid.

22 McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA

on the assumption that Oicse disputes had been resolved in favor

of the State for as we have held we are . . . unable to tell how the

jury resolved these matters . . .

203 A 204— DISSENT

AIcGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA 23

c

In my view, tlie cases discussed above establish beyond

peradventure the following propositions. First, due

process of law requires the States to protect individuals

against the arbitrary exercise of state power by assuring

that the fundamental policy choices underlying any exer

cise of state power are explicitly articulated by some re

sponsible organ of state government. Second, due

process of law is denied by state procedural mechanisms

that allow for the exercise of arbitrary power without

providing any means whereby arbitrary action may be

reviewed or corrected. Third, where federally protected

rights are involved due process of law is denied by state

procedures which render inefficacious the federal judicial

machinery that has been established for the vindication

of those rights. If there is any way in which these prop

ositions must be qualified, it is only that in some circum

stances the impossibility of certain procedures may be

sufficient to permit state power to be exercised notwith

standing their absence. Cf. Carroll v. President and

Commissioners, 393 U. S. 175, 182, 184-185 (1968). But

the judgment that a procedural safeguard otherwise re

quired by the Due Process Clause is impossible of appli

cation in particular circumstances is not one to be lightly

made. This is all the more so when, as in the present

cases, the argument of impossibility is not made by the

parties before us, but only by this Court. Before we

conclude that capital sentencing is inevitably a matter

of such complexity that it cannot be carried out in

consonance with the fundamental requirements of due

process, we should at the very least examine the mecha

nisms developed in not incomparable situations and pre

viously approved by this Court. Therefore, before exam

ining the specific capital sentencing procedures at issue

in these cases in light of the Due Process Clause, I am

203 & 204—DISSENT

compelled to discuss both the mechanisms available for

the control of arbitrary action and the nature of the

capital sentencing process.

24 McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA

II

A legislature which has determined that the State

should kill some but not all of the persons whom it has

convicted of certain crimes must inevitably determine

how the State is to distinguish those who are to be killed

from those who are not. Depending ultimately on the

legislature’s notion of wise penological policy, that dis

tinction may be hard or easy to make."" But capital

sentencing is not the only difficult question with which

legislatures have ever been faced. At least since Way-

man v. Southard, 10 Wheat. 1 (1825), we have recognized

that the Constitution does not prohibit Congress from

dealing with such questions by delegating to others the

responsibility for their determination. It is not my pur

pose to trace in detail either the sources and scope of

the delegation doctrine or the extent to which it is

applicable to the States through the Due Process Clause.

Tt is sufficient to state that in my view, whatever the

sources of the doctrine,21 its application to the States

“ It is essential to bear in mind that the complexity of capital

sentencing; determinations is a function of the penological policy

applied. A State might conclude, for example, that murderers should

lie sentenced to death if and only if they had committed more than

one such such crime. Application of such a criterion to the facts of

any particular ease would then be relatively simple.

As applied to the Federal Government, the doctrine appears to

have roots both in the constitutional requirement of separation of

powers—not. of course, applicable itself to the States, Dreyer v.

Illinois, 1S7 U. S. 71, S.3-S4 (1902): Sweezy v. New Hampshire, 354

IT. S. 234. 255 (1957)—and in the Due Process Clause of the Fifth

Amendment. See, e. g., Wayman v. Southard, 10 Wheat. 1, 13-14

(1S25) (argument of counsel) (due process and separation of pow

ers); Field v. Clark', 143 U. S. 649, 692 (1S92) (separation of powers);

203 & 204—DISSENT

as a matter of due process* 22 is merely a reflection of

the fundamental principles of due process already dis

cussed: in my Brother Harlan ’s words, the delegation

doctrine

“ insures that the fundamental policy decisions in

our society will be made not by an appointed official

but by the body immediately responsible to the peo

ple [and] prevents judicial review from becoming

merely an exercise at large by providing the courts

with some measure against which to judge the offi

cial action that has been challenged.” Arizona v.

California, 373 U. S. 546. 626 (1963) (dissent).23

My intention here is merely to provide an admittedly

brief sketch of the several mechanisms which Congress

has employed to assure that even with regard to the

most complex and intractable problems, delegation by

Carter v. Carter Coal Co.. 29S U. S. 238, 310-312 (1936) (due prof

ess). The two doctrines are not unrelated: in the words of Mr.

Justice Brandeis, “ The doctrine of tho separation of powers was

adopted by the Convention of 1787, not to promote efficiency but

to preclude the exercise of arbitrary power.” Myers v. I nited States.

272 U. S. 52, 293 (1926) (dissent).

22 At least since Yick Wo v. Hopkins. 118 U. S. 356 (1886), we

have indicated that due process places limits on the manner and

extent to which a state legislature may delegate to others powers

which the legislature might admittedly exercise itself. E. g., Eubank

v. Richmond, 226 U. S. 137 (1912): Embree v. Kansas City Road

District, 240 IT. S. 242 (1916); Browning v. Hooper, 269 U. S. 396

(1926); Cline v. Frink Dairy Co., 274 IT. S. 445. 457. 465 (1927);

Miller v. Schoene, 276 1’ . S. 272 (1928) ; Seattle Trust Co. v. Roberge„

278 U. S. 116 (1928); Louisiana v. United States, 380 U. S. 145

(1965); Giaecio v. Pennsylvania, 382 IT. S. 399 (1966). See Jaffe,

Law Making by Private Groups, 51 Harv. L. Rev. 201 (1937).

23 The passage quoted is explicitly an exegesis on the separation o f

powers. The point here is that, as discussed above, precisely the

same functions are performed by the Due Process Clause. For a

recent and original analysis to precisely the same effect, see K. Davis,

Administrative Law Treatise §§2.00-2.00-6 (Supp. 1970).

McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA 25

203 & 204—DISSENT

Congress of the power to make law has been subject to

controls which limit the possibility of arbitrary action

and which assure that Congress retains the responsibility

for ultimate decision of fundamental questions of na

tional policy. With these mechanisms in mind, I intend

briefly to discuss the considerations relevant to the prob

lem of capital sentencing with an eye to the question

whether it may responsibly be said that all of these

mechanisms are impossible of application by the States

to the capital sentencing process.

A

At the outset, candor compels recognition that our

cases regarding the delegation by Congress of lawmaking

power do not always say what they seem to mean. Ken

neth Culp Davis has been instrumental in pointing out

the “ unreality” 24 of judicial language appearing to direct

attention solely to the presence or absence of statutory

“ standards” 25 or an “ intelligible principle “G by which

delegated authority may be guided. See generally 1 Ad

ministrative Law Treatise §§ 2.00—2.05 (1958). In his

words,

“The difficulty and complexity of some types of

policy determination requires that the legislative

body should be allowed to provide for the adminis

trative working out of basic policy through the use

of specialized tribunals which use the common-law

method of concentrating upon one particular, nar

row, and concrete problem at a time. The protec

tion of advance legislative guidance is of little or

26 McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA

24 1 K Davis, Administrative Law Treatise §2.03, at 82 (1958).

25 E ' g,y Yakus v. United States, 321 II. 8. 414, 423-424 (1944).

20 The phrase is Mr. Chief Justice Taft’s, from Hampton A Co. v.

United States, 276 IT. S. 394, 409 (1928).

203 & 204—DISSENT

no consequence as compared with the protection that

can and should be provided through adequate pro

cedural safeguards, appropriate legislative supervi

sion or reexamination, and the accustomed scope

of judicial review.

“The protection that comes from a hearing with a

determination on the record, from specific findings

and reasons, from opportunity for outside critics to

compare one case with another, from critical super

vision by the legislative authority . . . and from

judicial review—all this is likely to be superior to

protection afforded by definiteness of standards.” 1

Administrative Law Treatise, §§ 2.05, at 98-99, 2.09,

at 111 (1958)A7

The point made by Professor Davis has, I think, often

been recognized by Congress. It is not surprising, then,

to see that in many instances Congress has focused its

attention much less upon the definition of precise statu

-7 Professor Davis lias just recently suggested that, insofar as it

presupposes a search for legislative standards, the doctrine prohibit

ing undue delegation of legislative power be explicitly abandoned.

“The time has come for the courts to acknowledge that the non

delegation doctrine is unsatisfactory and to invent better ways to

protect against arbitrary administrative power.

“ The non-delegation doctrine can and should be altered to turn it

into an effective and useful judicial tool. Its purpose should no

longer be either to prevent delegation of legislative power or to

require meaningful statutory standards; its purpose should be the

much deeper one of protecting against unnecessary and uncontrolled

discretionary power. The focus . . . should be on the totality of

protections against arbitrariness, including both safeguards and stand

ards.” Administrative Law Treatise, §2.00, at 40 (Supp. 1970).

Adoption of this approach, he suggests, would cause the delegation

doctrine to “merge with the concept of due process.” Id., §2.00-6,

at 58.

McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA 27

203 & 204—DISSENT

tory standards than on the creation of other means ade

quate to assure that policy is set in accordance with

congressional desires and that individuals are treated

according to uniform principles rather than administra

tive whim. Viewed in this light, our cases may be con

sidered as illustrating at least three legislative techniques.

First. In a number of instances, Congress lias in fact

undertaken to regulate even rather complex questions by

the prescription of relatively specific standards. It is cer

tainly an open question whether determining what con

duct should be subject to criminal sanctions is any more

difficult than determining what those sanctions should be;

yet Congress and the state legislatures as well have regu

larly passed criminal codes embodying, in the main, stat

utes directed at specifically and narrowly defined con

duct.-3 Similarly, the Congress resolved what was

certainly one of the most delicate and complex questions

before it in recent years— the extent, if any, to which the

national interest warranted federal regulations of organi

zations, including political parties, infiltrated by. domi

nated by, or subject to foreign control— not by leaving

the matter to anyone else but by defining with careful

particularity the characteristics that were required before

an organization could be subject to such regulation. See

50 U. S. C. §§ 782 (3). (4), (4A ), (5 ); Communist Forty

v. SACB, 367 U. S. 1 (1961). Congressional response to

the complex and intractable problems of the Depression

era occasionally took a similar form. Thus the Act ap

proved in United States v. Rock Royal Co-Op. 307 U. S.

533 (1939), stated a congressional policy to restore parity

prices in milk, defined the term, and delegated to the Sec-

28 Of course, where Congress has intended only to provide crim

inal sanctions intended to further a regulatory scheme it has often

simply made criminal the willful violation of administrative regula

tions rather than enact statutes outlawing specific conduct. E. g., 26-

V. S. C. § 7203.

28 McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA

203 & 204— DISSENT

retary of Agriculture only the power to issue orders in

terms themselves specified in the Act, commanding mini

mum prices to be determined in accordance with pre

scribed standards, to be applicable in areas where prices

had fallen below the limit set by Congress. See id., at

o75-577.

Second. In other circumstances, Congress has granted

to others the power to prescribed fixed rules to govern

future activity and adjudications. Such delegations of

power permit the legislature to declare the end sought

and leave technical matters in the hands of experts,20 or

to leave to others the task of devising specific rules to

carry out congressional policy in a variety of factual situ

ations.2'1 Where, as is often the case, even major policy

decisions may turn on specialized knowledge and exper

tise beyond legislative ken. delegation of rulemaking

power may be made under broad standards to a body

chosen for familiarity with the subject matter to be regu

lated.21 But entirely aside from whatever procedural

protections may be afforded interested parties prior to

the promulgation of administrative rules,* 31 32 the very

nature of the rulemaking process provides significant

guarantees both of evenhanded treatment and of ulti

mate legislative supervision of fundamental policy ques

-nE. g.. Battfield v. Strnnahan. 102 U. S. 470 (1904) (congres

sional directive lo prohibit importation of tea that is impure or unfit

for consumption: standards of purity and fitness to be prescribed

by administrator).

so E. g.. United Staten v. Grimaud, 220 U. S. 506 (1911) (delega

tion of power to make regulations for use of national forests to “ im

prove and protect” the forests).

31 E. g„ Red Lion H’ranting Co. v. FCC. 395 TT. S. 367 (1969)

(“ fairness doctrine” ) : NRC v. United Staten, 319 U. S. 190 (1943)

(regulation of network-station contracts).

:l-> Most substantive exercises of federal rulemaking power are now

governed by the Administrative Procedure Act, 5 l T. S. C. § 551

ct seq. (Supp. X, 1969).

McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA 20

203 tV 204— DISSENT

tions. Significantly, we have upheld delegations of rule

making power without standards to guide its exercise only

in two narrowly limited classes of cases.33 We have

otherwise searched the statute, the legislative history, and

the context in which the regulation was enacted in order

to discern and articulate a legislative policy.34 The point

is not whether an intelligible legislative policy was or was

not correctly inferred from the statute. The point is

that such a policy, once expressly articulated, not only

serves to guide subsequent administrative and judicial

action but also provides a basis upon which the legislature

may determine whether power is being exercsied in ac

cordance with its will.35 Where no intelligible resolution

of fundamental policy questions can be discerned from

a statute or judicial decisions, the rulemaking process

itself serves to make explicit the agency’s resolution of

these questions, thus allowing for meaningful legislative

33 Ever since Way wan v. Southard, 10 Wheat. 1 (1S25), we have

regularly upheld congressional delegation to courts and agencies of

the power to make their own rules of procedure. Cf. 5 U. S. C.

§ 553 (b) (3) (A) (Supp. V, 1969), excepting procedural rules from

the requirements otherwise imposed on rulemaking procedures by

the Administrative Procedure Act. Second, we have regularly upheld

federal statutes which seek to further state policies by adopting or

enforcing state law. E. g., United States v. Howard, 352 U. S. 212

(1957).

34 Fahey v. Mallonee, 332 U. S. 245, 250, 253 (1947), found broad

statutory standards drawing content from “ accumulated experience”

which “ established well-defined practices.” In American Trucking

Ass?w. v. United States, 344 II. S. 298 (1953), we sustained an exer

cise of rulemaking power on the basis that the rules, which dealt with

matters not explicitly mentioned in the statute, were reasonably

necessary to prevent frustration of specific provisions of the Act.

Id., at 310-313.

35 Compare Perkins v. Lukens Steel Co., 310 U. S. 113 (1940), with

66 St at. 3081,41 U. S. C. § 43a; compare United States v. Wunderlich,

342 U. S. 98 (1951), with 68 Stat. 81, 41 U. S. C. §§ 321-322.

30 McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA

203 & 204— DISSENT

supervision/6 as well as providing bases both for judicial

review of agency action supposedly premised on the

rule* 37 and for refinement of an old rule in light of

experience gained in its administration.

1 hird. Perhaps the most common legislative tech

nique for dealing with complex questions that will arise

in a myriad of factual contexts has been the delegation

to another group of lawmaking power which may be exer

cised either through rulemaking or the adjudication of

individual cases, with choice between the two left to

the agency’s judgment. Such schemes, while allowing

broad flexibility for the working out of policy on a case-

by-case basis, nevertheless have invariably provided sub

stantial protections to insure against arbitrary action

and to guarantee that underlying questions of policy are

considered and resolved. As with the delegation simply

of rulemaking power, we have often found substantial

guidance in the language and history of the governing

statute. New York Central Securities Corp. v. United

States, 287 U. S. 12 (1932); Radio Commission v. Nelson

Bros. Co., 289 U. S. 266 (1933); Sunshine Anthracite Coal

Co. v. Adkins, 310 U. S. 381 (1940). Agency action un

der such delegations must typically be premised upon an

explanation of both the findings and reasons for a given

decision, e. g., 5 U. S. C. § 557 (c)(3 ) (Supp. V, 1969),

a requirement we have held to be far more than an empty

formality. SEC v. Chenery Corp., 318 U. S. 80 (1943);

Phelps Dodge Corp. v. NLRB, 313 U. S. 177, 196-197

(1941). The regular course of adjudication by a con

McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA 31

3(1 See, e. g., congressional revision of the Federal Trade Commis

sion’s rule regarding cigarette advertising, 29 Fed. Reg. 8825 (1964),,

in Tub. L. No. 89-92, 79 Stat. 282 (1965).

37 Accardi v. Shaughnessy, 347 U. S. 260 (1954).

203 & 204—DISSENT

tinuing body required to explain the reasoning upon

which its decisions are based results in the accumulation

of a body of precedent from which, over time, general

principles may be deduced. See, e. g., the history of the

Federal Communications Commission’s “ fairness doc

trine,” traced in Red Lion Broadcasting Co. v. FCC, 395

U. S. 367, 375-379 (1969). We have often noted the

importance of administrative or judicial review in pro

viding a check on the exercise of arbitrary power, Mulford

v. Smith, 307 U. S. 38. 49 (1939); American Bower <6

Light Co. v. SEC, 329 U. S. 90, 105 (1946), and we have

made clear that judicial review is designed to reinforce

internal protections against arbitrary or unconsidered

action while leaving questions of policy to the agency

or the Congress. Thus we have withheld approval from

agency action unsupported by an indication of the reasons

for that action, Phelps Dodge Corp. v. NLRB, supra;

where the reasons articulated were improper, Sicurella v.

United States, 348 U. S. 385 (1955), even though the

record might well support identical action taken for dif

ferent reasons, SEC v. Chenery Corp., supra; where ad

ministrative expertise relevant to the solution of a prob

lem had never been brought to bear upon it. FCC v. RCA

Communications, Inc., 346 U. S. 86, 91-92 (1953); where

an apparent conflict in administrative rationales had

never been explained by the agency, Barrett Line, Inc. v.

United States, 326 U. S. 179 (1945); and where a change

in agency policy had taken place after the particular

adjudication concerned. NLRB v. Gissell Packing Co.,

395 U. S. 575, 615-616 (1969).

Combination of rulemaking and adjudicatory powers

has proved a particularly useful tool in situations where

prescription of detailed standards in the first instance

has been difficult or impossible for the Congress, yet the

variety of factual situations has rendered particularly im

portant protection against random or arbitrary decisions.

32 McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA

203 & 204—DISSENT

Thus in Lie-liter v. United States, 334 U. S. 742 (1948),3S

this Court dealt with the provisions of the original Rene

gotiation Act, passed in April of 1942, which directed

various administrative officials to proceed with com

pulsory “renegotiation" of contracts that had resulted in

“excessive profits.” The Act as originally passed at

tempted no definition of such profits; within four months,

however, administrative practice had solidified about a

list of six factors to be considered in determining whether

profits were excessive; slightly more than two months

later, these factors were adopted by Congress in an

amendment to the Act. In upholding the original Act

against a claim of excessive delegation, we stressed both

the rapid development of generally applicable standards,

id., at 766, 769, 771, 773-774, 77S, 783, and the availabil

i t y of judicial review to check arbitrary or inconsistent

administrative action. Id., at 770, 771, 786-787.

B

The next question is whether there is anything inherent

in the nature of capital sentencing that makes impossible

the application of any or all of the means that have been

elsewhere devised to check arbitrary action. I think it

is fair to say that the Court has provided no explanation

for its conclusion that capital sentencing is inherently in

capable of rational treatment. Instead, it relies pri

marily on the Report of the [British] Royal Commission

on Capital Punishment, which reaches conclusions sub

stantially identical with the following urged in 1785 by

Archdeacon William Paley to justify England’s “ Bloody

Code” of more than 250 capital crimes:

“ [T]he selection of proper objects for capital

punishment principally depends upon circumstances,

■'18 Lirhter has been termed by Professor Davis “ in some respects

flie greatest delegation upheld by the Supreme Court.” 1 K. Davis,

Administrative Law Treatise §2.03, at 86 (1958).

McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA 33

203 iV 204—DISSENT

McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA

which, however easy to perceive in each particular

case after the crime is committed, it is impossible to

enumerate or define beforehand; or to ascertain, how

ever, with that exactness, which is requisite in legal

descriptions. Hence, although it be necessary to fix,

by precise rules of law, the boundary on one side . . .

yet the mitigation of punishment . . . may, without

danger, be intrusted to the executive magistrate,

whose discretion will operate upon those numerous,

unforeseen, mutable and indefinite circumstances,

both of the crime and the criminal, which constitute

or qualify the malignity of each offence. . . . For

if judgment of death were reserved for one or two

species of crimes only . . . crimes might occur of

the most dangerous example, and accompanied by

circumstances of heinous aggravation, which did not

fall within any description of offenses that the laws

had made capital, and which consequently could not

receive the punishment their own malignity and the

public safety required. . . .

“ The law of England is constructed upon a differ

ent and a better policy. By the number of statutes

creating capital offences, it sweeps into the net every

crime which, under any possible circumstances, may

merit the punishment of death: but, when the execu

tion of this sentence comes to be deliberated upon, a

small proportion of each class are singled out, the

general character, or the peculiar aggravations, of

whose crimes, render them fit examples of public jus

tice. . . . The wisdom and humanity of this design

furnish a just excuse for the multiplicity of capital

offences, which the laws of England are accused of

creating beyond those of other countries.” W. Paley,

Principles of Moral and Political Philosophy 399-401

(6th Am. ed. 1S10).

208 & 204—DISSENT

Significantly, the Court neglects to mention that the rec

ommendations of the Royal Commission on Capital Pun

ishment found little more favor in England than Arch

deacon Paley’s. For the “ British have been unwilling to

empower either courts or juries to decide on life or

death, insisting that death should be the sentence of

the law and not of the tribunal.” Symposium on Capital

Punishment, 7 N. Y. L. F. 249, 253 (1961.) ( H. Wechsler).

Beyond the Royal Commission’s Report, the Court sup

ports its conclusions only by referring to the standards

proposed in the Model Penal Code 30 and judging them

less than perfect. The Court neglects to explain why the

impossibility of perfect standards justifies making no at

tempt whatsoever to control lawless action. In this con

text the words of Mr. Justice Frankfurter are instructive:

It is not for this Court to formulate with particu

larity the [standards] which would satisfy the Four

teenth Amendment. No doubt, finding a want of

such standards presupposes some conception of what

is necessary to meet the constitutional requirement

we draw from the Fourteenth Amendment. But

many a decision of this Court rests on some inarticu

late major premise and is none the worse for it. A

standard may be found inadequate without the ne

cessity of explicit delineation of the standards that

would be adequate, just as doggerel may be felt not

to be poetry without the need of writing an essay

on what poetry is.” Niemotko v. Maryland, 340

U. S. 268, 285 (1951) (concurring opinion).

But although T find the Court’s discussion inadequate,

there remains the question whether capital sentencing is

inherently incapable of being carried out under proce-

“ And, as the Court notes, substantially adopted in one proposal

ot the National Commission on Reform of the Federal Criminal Laws.

McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA 85

203 & 204— I)ISSi:XT

dures that provide the safeguards necessary to protect

against arbitrary determinations. I think not. I reach

this conclusion for the following reasons.

First. It is important at the outset to recognize that

two separate questions are involved. The first question

is what ends any given State seeks to achieve by impos

ing the death penalty. The second question is whether