Van Meter v. Barr Brief in Support of Appellant for Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

June 15, 1992

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Van Meter v. Barr Brief in Support of Appellant for Amici Curiae, 1992. d6d22088-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d063ed53-f108-4f3b-80ce-aa2059e381d6/van-meter-v-barr-brief-in-support-of-appellant-for-amici-curiae. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

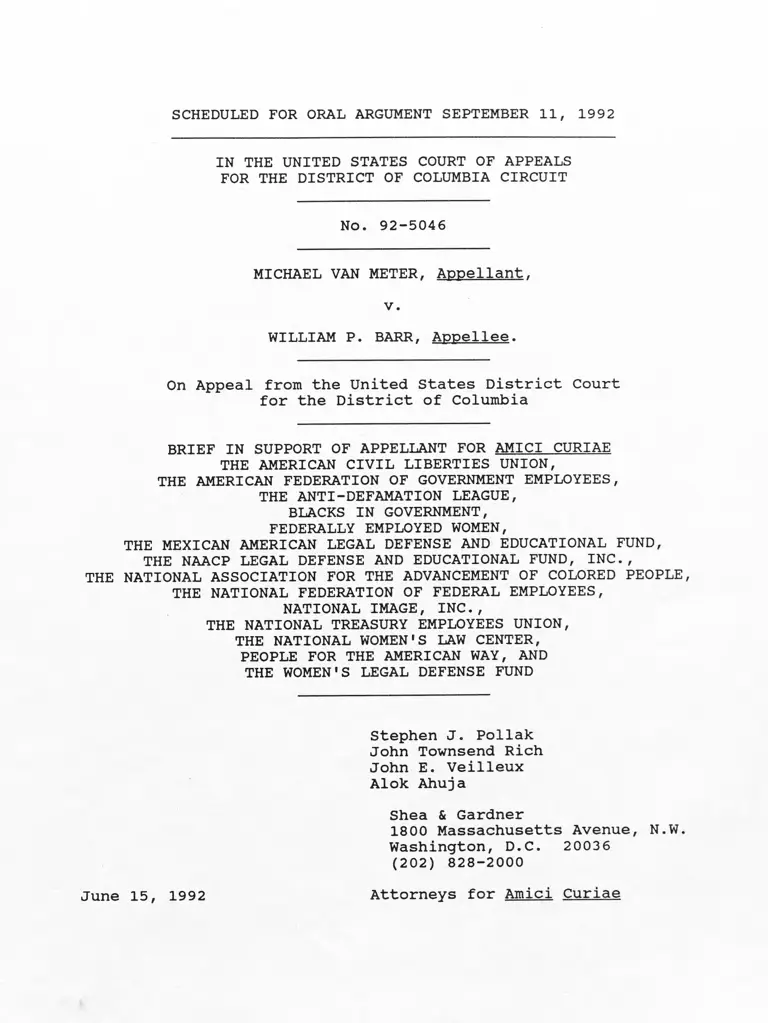

SCHEDULED FOR ORAL ARGUMENT SEPTEMBER 11, 1992

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

No. 92-5046

MICHAEL VAN METER, Appellant,

v.

WILLIAM P. BARR, Appellee.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the District of Columbia

BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF APPELLANT FOR AMICI CURIAE

THE AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION,

THE AMERICAN FEDERATION OF GOVERNMENT EMPLOYEES,

THE ANTI-DEFAMATION LEAGUE,

BLACKS IN GOVERNMENT,

FEDERALLY EMPLOYED WOMEN,

THE MEXICAN AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND,

THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.,

THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE,

THE NATIONAL FEDERATION OF FEDERAL EMPLOYEES,

NATIONAL IMAGE, INC.,

THE NATIONAL TREASURY EMPLOYEES UNION,

THE NATIONAL WOMEN'S LAW CENTER,

PEOPLE FOR THE AMERICAN WAY, AND

THE WOMEN'S LEGAL DEFENSE FUND

Stephen J. Poliak

John Townsend Rich

John E. Veilleux

Alok Ahuja

Shea & Gardner

1800 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 828-2000

June 15, 1992 Attorneys for Amici Curiae

CERTIFICATE DISCLOSING INTERESTS OF AMICI

Pursuant to Rule 6A of the Rules of this Court, the amici

filing this brief submit this statement of their general natures

and purposes and their interests in this case.

The American Civil Liberties Union ("ACLU") is a nationwide,

nonprofit, nonpartisan organization with nearly 300,000 members

dedicated to preserving and enhancing the fundamental civil

rights and civil liberties embodied in the Constitution and civil

rights laws of this country. The ACLU has long been involved in

the effort to eliminate racial discrimination in our society.

The Women's Rights Project of the ACLU Foundation was established

to work toward the elimination of gender-based discrimination in

our society. In pursuit of these goals, the ACLU has partici

pated in numerous discrimination cases before this and other

courts. The ACLU and the ACLU Women's Rights Project were active

in the effort to secure passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1991.

The American Federation of Government Employees is a labor

organization that represents over 750,000 federal employees.

Included in such representation are scores of pending EEO dis

crimination cases and administrative actions arising prior to the

enactment of the Civil Rights Act of 1991. These cases raise the

issue of the retroactive application of the Act's amendments to

pending claims, as does the instant case.

Since 1913, the Anti-Defamation League ("ADL") has pursued

the objective set out in its Charter "to secure justice and fair

treatment to all citizens alike." In order to further this

objective, ADL has fought steadfastly to remove barriers which

have prevented individuals from fully enjoying the rights pro

tected by federal civil rights laws. Most recently, ADL sup

ported the enactment of the Civil Rights Act of 1991 as an effort

to redress inequities stemming from several Supreme Court

decisions. ADL believes the retroactive enforcement of the Act

is consistent with the intent of Congress and is crucial to

protecting the interests of discrimination victims.

Blacks In Government ("BIG") is a nonprofit, nonpartisan

organization of government employees at federal, state, and local

government levels. BIG was incorporated in Washington, D.C., in

1976 for the purpose of promoting equality of opportunity and

combatting racism in government employment nationwide. It

functions as an advocacy organization, an employee support group,

and a professional association for black government employees1

concerns with equal opportunity and excellence in public service.

BIG includes more than 150 chapters covering all states in the

United States.

11

Federally Employed Women, Inc. ("FEW"), is an international

non-profit organization representing over one million women

employed by the federal government. Since its inception in 1968,

its primary objective has been to eliminate sex discrimination

and enhance career opportunities for women in government. Recog

nizing the need for full enforcement of Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, as amended, FEW strongly supported enactment

of the Civil Rights Act of 1991 and remains committed to ensuring

that the procedures and remedies under that statute are fully

available to all victims of employment discrimination in the

federal sector.

The Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund

("MALDEF") is a national civil rights organization established in

1967. Its principal objective is to secure, through litigation

and education, the civil rights of Hispanics living in the United

States. In this context, MALDEF has filed employment discrimina

tion suits on behalf of Hispanic federal employees in the past,

MALDEF has such cases currently pending in the federal courts,

and MALDEF expects to bring additional cases on behalf of

Hispanic federal employees in the future. MALDEF thus has a

substantial interest in the procedures and remedies available to

victims of employment discrimination in the federal sector.

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. ("LDF"),

is a non-profit corporation formed to help African Americans

secure their constitutional and civil rights by means of liti

gation. For many years, LDF attorneys have represented parties

in litigation before the Supreme Court of the United States and

in other federal and state courts in cases involving a variety of

race discrimination and remedial issues. E.g.. Lvtle v.

Household Mfg., Inc.. 494 U.S. 545 (1990); Patterson v. McLean

Credit Union. 491 U.S. 164 (1989); Bazemore v. Friday. 478 U.S.

385 (1986); Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co.. 424 U.S. 747

(1976); Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody. 422 U.S. 405 (1975); Griggs

v. Duke Power Co.. 401 U.S. 424 (1971). LDF believes that its

experience in this area of litigation and the research that it

has done will assist the Court in this case.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored

People ("NAACP") is an organization dedicated to the furtherance

of racial equality and social and economic justice in this

country. To promote these ends, the NAACP and its members engage

in activity protected by the United States Constitution, in

cluding petitioning the government for the redress of grievances.

For more than twenty years, the NAACP and its members throughout

the United States have assisted workers in utilizing Title VII of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to challenge employment discrimina

tion against minorities and women. The NAACP has urged the

Congress to strengthen Title VII and other provisions of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, which ultimately resulted in enactment

of amendments to Title VII in the Civil Rights Act of 1991.

iii -

The National Federation of Federal Employees ("NFFE") repre

sents nearly 150,000 federal employees nationwide. There are

approximately 400 NFFE locals from a cross-section of the govern

ment, e.g.. Department of Veterans' Affairs, General Services

Administration, Army, Passport Agency, and Bureau of Indian

Affairs. Members of NFFE bargaining units have cases in progress

in which claims of unlawful employment discrimination are being

investigated and adjudicated. Many of these cases were pending

at the time of the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1991. The

decision of this Court regarding the retroactivity of the Act

will have a major impact on the outcome of the cases of bar

gaining unit employees represented by NFFE.

National Image, Inc. ("IMAGE"), is a non-profit membership

organization representing thousands of Hispanic men and women

employed by federal, state and local governments. Since its

inception in 1972, IMAGE'S primary objective has been to enhance

career opportunities for Hispanics in government and eliminate

Hispanic national origin discrimination. Recognizing the need

for full enforcement of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, IMAGE strongly supported enactment of the Civil Rights Act

of 1991. Federal employee members of IMAGE have employment

discrimination cases pending which will be affected by this

Court's decision concerning the retroactivity of the Civil Rights

Act of 1991.

The National Treasury Employees Union ("NTEU") is an

independent federal sector labor organization that represents

approximately 150,000 federal employees nationwide. In addition

to serving as their collective bargaining representative, NTEU

frequently conducts litigation in federal court on behalf of its

members, and all federal employees, seeking to vindicate their

statutory and constitutional rights, including rights arising

under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended.

NTEU has pending in various administrative forums employment

discrimination claims by numerous federal employees involving

conduct occurring prior to November 21, 1991. NTEU is also

currently challenging, as contrary to the Civil Rights Act of

1991, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission's policy

guidance concluding that the damages provisions of that Act do

not apply to pending cases. NTEU v. KEMP. No. 92-0115-BAC (N.D.

Cal.). In addition, NTEU represents the plaintiff in Pitts v.

Sullivan. No. 90-2037 (SSH) (D.D.C.), a federal sector employment

discrimination case originally set for bench trial on May 26,

1992, but which has been stayed pending the outcome of this case.

The National Women's Law Center ("NWLC") is a non-profit

legal advocacy organization dedicated to the advancement and

protection of women's rights and the corresponding elimination of

sex discrimination from all facets of American life. Since 1972,

NWLC has worked to secure equal opportunity in the workplace

through the full enforcement of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act

iv

of 1964, as amended. NWLC strongly supported enactment of the

Civil Rights Act of 1991 and is committed to assuring that the

amendments made by the Act are applied to litigation pending on

the date of its enactment.

People For the American Way ("People For") is a nonpartisan,

education-oriented citizens' organization established to promote

and protect civil and constitutional rights. Founded in 1980 by

a group of religious, civic and educational leaders devoted to

our nation's heritage of tolerance, pluralism and liberty, People

For now has over 300,000 members nationwide. People For has been

actively involved in efforts to combat discrimination and promote

equal rights, including supporting the enactment of the Civil

Rights Act of 1991, participating in civil rights litigation, and

conducting programs and studies directed at reducing problems of

bias, injustice and discrimination.

The Women's Legal Defense Fund ("WLDF") is a national advo

cacy organization that was founded in 1971 to advance women's

equal participation in all aspects of society and to promote

policies which improve the lives of women and their families.

WLDF represents women and men challenging barriers to sexual

equality, and is particularly concerned with combatting sex

discrimination in employment through litigation of significant

cases, public education, and advocating for strong equal employ

ment opportunity laws and enforcement. WLDF supported enactment

of the Civil Rights Act of 1991 and is committed to working for

effective interpretation and strong enforcement of the law.

None of these entities has parent companies, subsidiaries,

or affiliates that have issued shares or debt securities to the

public.

Stephen J. Poliak

Shea & Gardner

1800 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 828-2000

June 15, 1992 Attorney for Amici Curiae

V

CERTIFICATE AS TO PARTIES. RULINGS. AND RELATED CASES

A. Parties and Amici

All parties, intervenors and amici appearing below and in

this Court are listed in the Brief of Appellant.

Amici notified the Court of their intention to file this

brief, accompanied by written consents of all parties, on

March 23, 1992.

B. Rulings Under Review

Denial of Van Meter's motion to amend his complaint to

include a claim for compensatory damages and a request for a jury

trial pursuant to § 102 of the Civil Rights Act of 1991. 778 F.

Supp. 83 (D.D.C. Dec. 18, 1991) (Gesell, J.), reprinted at J.A.

229-36.

C. Related Cases

Related cases are described in the Brief for Appellant.

Stephen J. Poliak

Shea & Gardner

1800 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 828-2000

June 15, 1992 Attorney for Amici Curiae

- vi

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

CERTIFICATE DISCLOSING INTERESTS OF AMICI ................... i

CERTIFICATE AS TO PARTIES, RULINGS AND RELATED CASES . . . . V

TABLE OF CONTENTS............................................... Vl

TABLE OF A U T H O R I T I E S ........................................ viii

INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ........................ 1

ARGUMENT . . 5

I. The Canon of Construction That Waivers of Sovereign

Immunity Must Be Clearly Expressed Does Not Require

That the Text of the 1991 Act State Explicitly That

§ 102 Applies to Pending Cases .......................... 5

A. This Court and Seven Other Circuits Applied

§ 717 of Title VII to Pending Cases Despite

the Absence of an Unequivocal Waiver of

Sovereign Immunity as to Such Claims and

those Decisions Warrant the Same Result Here . . . 7

B. Congress' Broad Waiver of Federal Immunity in

Title VII Makes It Inappropriate To Require

an Unequivocal Expression of Every Circum

stance to Which It Extends......................

C. Recent Supreme Court Cases Not Involving

Title VII Reaffirm That the Canon Requiring

Waivers To Be "Unequivocally Expressed" Is

Satisfied Where Congress Has Waived Immunity

Over a Certain Subject Matter ...............

II. Application of § 102 of the 1991 Civil Rights Act to

Federal Employee Cases Pending in Court Does Not

Undermine Title VII's Requirement That Administra

tive Remedies Be Invoked Before Suit .............

A. The Conditions on the Right To Sue for

Federal and Private Employees Are Essentially

the S a m e .................................... . 18

- vii

Page

B. Allowing Federal Title VII Plaintiffs To Add

Compensatory Damage Claims and To Have a Jury

Trial in Court Will Not Undermine the

Requirement That Federal Employees Invoke

Administrative Remedies Before Suit ................ 24 III.

III. The United States Has Taken Conflicting

Positions on Retroactivity Issues Subsequent

to the Bowen Decision................................28

CONCLUSION..................................................... 3 4

STATUTORY ADDENDUM ........................................... la

APPENDICES (in separate volume)

viii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES: Page

Adams v. Brinegar, 521 F.2d 129 (7th Cir. 1975) . . . . . . 9

*Ardestani v. INS, 112 S. Ct. 515 (1991) . . . . . . 15, 16, 17

Bailes v. United States. 112 S. Ct. 1755 (1992) . . . . . . 30

Bennett v. New Jersey. 470 U.S. 632 (1985)......... 30, 31

Berger v. United States. 295U.S. 78 (1935) ............... 29

Bowen v. City of New York. 476 U.S. 467 (1986)............. 13

Bowen v. Georgetown Univ. Hoso.. 488 U.S. 204 (1988) . . passim

Bradley v. School Bd. of the City of Richmond,

416 U.S. 696 (1974) ................................ passim

Brown v. General Services Admin.. 507 F.2d 1300 (2d Cir.

1974), aff'd on other grounds. 425 U.S. 820 (1976) . . . 8

Brown v. General Services Admin.. 425 U.S. 820 (1976) . 8, 15

Bunch v. United States. 548 F.2d 336 (9th Cir. 1977) . . 9, 27

Campbell v. United States, 809 F.2d 563 (9th Cir. 1987) . . 11

Chandler v. Roudebush. 425 U.S. 840 (1976) ......... 14, 15, 21

Coles v. Penny. 531 F.2d 609 (D.C. Cir. 1976) ............. 13

Eastland v. Tennessee Valley Auth., 553 F.2d 364

(5th Cir.), cert, denied. 434 U.S. 985 (1977) . . . . . 9

Grubbs v. Butz, 514 F.2d 1323 (D.C. Cir. 1 9 7 5 ) ............. 21

*Hacklev v. Roudebush. 520 F.2d 108 (D.C. Cir. 1975) . . 13, 14

Huey v. Sullivan. No. 91-2908WM, 1992 U.S. App. LEXIS

11303 (8th cir. May 21, 1992) .......................... 6

*Irwin v. Veterans Admin.. Ill S. Ct. 453 (1990) . . . . passim

Johnson v. Greater Southeast Community Hosp. Corp^,

951 F . 2d 1268 (D.C. Cir. 1 9 9 1 ) ................. 17, 18, 23

Authorities chiefly relied on are marked with an asterisk.

CASES: ix Page

Kaiser Aluminum & Ghent. Corp. v. Bonjorno, 494 U.S.

827 (1990)................................................

*Koaer v. Ball. 497 F.2d 702 (4th Cir. 1974) ............. 8 , 9

Lee v. Sullivan, No. C-89-2873, 1992 U.S. Dist.

LEXIS 3612 (N.D. Cal. Mar. 26, 1992) . . . . . ......... 11

Library of Congress v. Shaw, 478 U.S. 310 (1986) . . . . 14, 15

Mangiaoane v. Adams. 661 F.2d 1388 (D.C. Cir. 1981)

Mahroom V. Hook, 563 F.2d 1369 (9th Cir. 1977),

cert, denied. 436 U.S. 904 (1978) ......................

Mondv v. Sec1v of the Army, 845 F.2d 1051 (D.C. Cir. 1988) . 13

Place v. Weinberger, 497 F.2d 412 (6th Cir. 1974),

cert, granted, vacated and remanded,

426 U.S. 932 (1976) .....................................9

Place v. Weinberger, 426 U.S. 932 (1976)................... 1°

^President v. Vance, 627 F.2d 353 (D.C. Cir. 1980) . . . 27, 28

Soerling v. United States, 515 F.2d 465 (3d Cir. 1975),

cert, denied, 426 U.S. 919 (1976) ............... ..

Sullivan v. Hudson. 490 U.S. 877 (1989) 16

*Thompson v. Sawyer. 678 F .2d 257 (D.C. Cir. 1982) 10

United states v. Kubrick, 444 U.S. Ill (1979) 16

United States v. Mott a z, 476 U.S. 834 (1986).................. 5

United States v. Nordic Village , Inc ,̂ 112 S. Ct.

1011 (1992) ......................................... '

United States Dep't of Energy v. Ohio, 112 S. Ct. g

1627 (1992) .............................................

Van Meter v. Barr. 778 F. Supp. 83 (D.D.C. 1991) . . . . Pass-X-̂

Wagner Seed Co. V. Bush, 946 F.2d 918 (D.C. Cir. 1991),

cert, denied. 112 S. Ct. 1584 (1992) .................

Weahkee v. Powell. 532 F.2d 727 (10th Cir. 1 9 7 6 ) ...........9

*Womack v. Lvnn, 504 F.2d 267 (D.C. Cir. 1974) ......... passim

X

STATUTES: Page

Administrative Procedure Act, as amended, 5 U.S.C.

§ 701 et sea. (1970)..................................... 26

Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988, Pub. L. 100-690, § 7342,

102 Stat. 4181, 4469-70, codified as amended at

8 U.S.C. § 1101(43) (supp. II 1990) ................... 33

Back Pay Act, as amended, 5 U.S.C. § 5596 (1970) ........... 26

Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended through 1990,

42 U.S.C. § 2000e et sea. (1988)................... passim

§ 706(b), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(b) (1988) ......... . 21, 22

§ 706(f)(1), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(f)(1) (1988) 22

§ 706(g), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(g) (1988) ............. 10

§ 717, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16 (1988).................. passim

§ 717(b), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16(b) (1988) ............. 19

§ 717(c), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16(c) (1988) . . . . 12, 19, 26

Civil Rights Act of 1991, Pub. L. 102-166, 105 Stat.

1071 (Nov. 21, 1991) 1

§ 1 0 2 ................................................. passim

§ 1 1 4 ..................................................... 19

D.C. Code § 23-1322 (1992) . ................................. 33

Equal Access to Justice Act, as amended, 5 U.S.C. § 504

and 28 U.S.C. § 2412 (1988) ............................ 16

Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972, Pub. L.

92-261, 86 Stat. 1 0 3 ....................................... 7

§ 14, 86 Stat. 112, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5 note (1989) . . 7

False Claims Act, as amended, 31 U.S.C.A.

§§ 3729-3733 (Supp. 1992) 33

Financial Institution Reform, Recovery, and Enforcement

Act of 1989, Pub. L. No. 101-73, § 217, 103 Stat.

183, 254-61 (1989)....................................... 33

12 U.S.C. § 1715z-4a (c) (1988) .......................... 30, 33

STATUTES: xi Page

28 U.S.C. § 1292(b) (1988) 2

28 U.S.C. § 2201 (1970)........................................ 26

42 U.S.C. § 1981 (1970)........................................ 26

REGULATIONS AND EXECUTIVE ORDERS:

29 C.F.R. § 1601.18(e) (1991) 22

29 C.F.R. § 1601.14(a) (1991) 21

29 C.F.R. § 1601.28(a)(1) (1991) ............................ 22

29 C.F.R. part 1613 (1991) ...................................19

§ 1613.213(a) 20

§ 1613.214(a) 20

§ 1613.215(a) 20

§ 1613.216.............................................20, 25

§§ 1613.216-.221 ..........................................20

§ 1613.231.................................................20

§ 1613.218..................... 25

§ 1613.281.............................................19, 20

29 C.F.R. part 1614, published at 57 Fed. Reg. 12634

(Apr. 10, 1992) 19, 25

Executive Order 11246, 3 C.F.R. 339 (1964-1965) 26

Executive Order 11478, 3 C.F.R. 803 (1966-1970) 26

BRIEFS:

Brief for the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation

(argued Feb. 26, 1991), FDIC v. Wright, 942 F.2d

1089 (7th Cir. 1991) (No. 90-2217)............. 29, 32, 33

BRIEFS: - xii Page

Brief for the United States (Aug. 18, 1990), U.S.

v. Fischbach & Moore. Inc.. Paul B. Murphy.

937 F .2d 1032 (6th Cir. 1991) (Nos. 90-5648

& 90-5649).................................. 30, 31, 32, 33

Brief for the United States (July 1, 1991),

U.S. v. Israel Discount Bank, Ltd..

No. 91-5026 (11th Cir.) ................... 30, 31, 32, 33

Brief for the United States (argued Oct. 3, 1989),

U.S. v. Ottati & Goss, Inc.. 900 F.2d 429

(1st Cir. 1990) (NOS. 89-1063 & 89-1065) . . . . 30, 32, 33

Brief for the United States (June 28, 1990),

U.S. v. Peooertree Apartments et al.,

George Bailes, Jr.. 942 F.2d 1555 (11th Cir.

1991) (No. 89-7850) ........................ 30, 31, 32, 33

Brief for the United States (Mar. 31, 1989),

U.S. V. R.W. Mever, Inc., 889 F.2d 1497

(6th Cir. 1989) (No. 88-2074) ...................... 30, 33

Brief for the United States (Apr. 10, 1990),

Saraisson v. U.S.. 913 F.2d 918 (Fed. Cir. 1990)

(No. 90-5034) ....................................... 30, 31

Memorandum for the United States (Apr. 1, 1992),

Bailes v. United States. 112 S. Ct. 1755

(1992) (No. 91-1075)..................................... 30

Opposition to Defendant's Memorandum Concerning

Retroactivity of the Bail Reform Amendment Act

(Apr. 22, 1992), U.S. v. Bostick. Crim. No.

F 14117-88 (D.C. Super. C t . ) ................... 30, 31, 33

Respondent Immigration & Naturalization Service's

Opposition to a Stay of Deportation (May 10,

1991), Avala-Chavez v. INS, 945 F.2d 288

(9th Cir. 1991) (NO. 91-70262)............. 30, 31, 32, 33

Response to Defendants' Motion to Strike Claims for

Damages and Penalties (response to motion filed

Oct. 6, 1989), U.S. v. Rent America. Inc.,

et al.. 734 F. Supp. 474 (S.D. Fla. 1990)

(No. 8 9-618 8-PAINE) ........................ 30, 31, 32, 33

United States' Memorandum in Response to Petition for

Rehearing, Place v. Weinberger, 426 U.S. 932 (1976)

(No. 74-116) ....................................... 9

SCHEDULED FOR ORAL ARGUMENT SEPTEMBER 11, 1992

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

No. 92-5046

MICHAEL VAN METER, Appellant,

v.

WILLIAM P. BARR, Appellee.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the District of Columbia

BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF APPELLANT FOR AMICI CURIAE

INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

On January 7, 1991, appellant Michael Van Meter, a Special

Agent of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, filed this Title

VII race discrimination case in the District Court. On Novem

ber 21, 1991, the day the Civil Rights Act of 1991 ("1991 Act"),

Pub. L. 102-166, 105 Stat. 1071, was signed and became effective,

appellant moved to amend his complaint to include a claim for

compensatory damages and a request for a jury trial pursuant to

§ 102 of the 1991 Act . -

11 Section 102 entitles both federal and private employee vic

tims of intentional discrimination to new remedies of compensa

tory damages (limited in amount) and a jury trial. The pertinent

provisions of § 102, the full text of which is set forth in an

appendix to Appellant's brief, are set forth in a Statutory

Addendum to this brief.

2

On December 18, 1991, the Court denied appellant's motion to

amend his complaint. Judge Gesell ruled that the 1991 Act and

its legislative history did not provide a clear enough expression

of Congress' intent to permit him to hold that Congress had

waived the sovereign immunity of the United States with respect

to claims of federal employees for compensatory damages and a

jury trial in employment discrimination cases that were pending

in district court at the time the 1991 Act was passed. 778 F.

Supp. 83, 86 (D.D.C. 1991), reprinted at J.A. 229, 234-35. That

ruling is here on interlocutory appeal pursuant to 28 U.S.C.

§ 1292(b).

Amici support appellant's arguments that under standard

rules of statutory construction, the plain language of the 1991

Act requires that it be read to apply to pending cases; and that

the judicial presumption in favor of retroactivity of remedial

statutes, exemplified by Bradley v. School Bd. of the City of

Richmond. 416 U.S. 696 (1974), dictates that the provisions

providing federal employee victims of intentional discrimination

with compensatory damages and a jury trial be applied to pending

cases.

Amici present three additional arguments that provide fur

ther support for the conclusion that the 1991 Act applies to

pending cases.

First, the canon of construction requiring that waivers of

sovereign immunity must be "unequivocally expressed" does not

require the text of the 1991 Act to state explicitly that § 102

3

applies to cases pending on the date of its enactment. The 1972

amendments to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which gave federal

employees the right to sue to enforce their rights to equal em

ployment opportunity, were applied retroactively by this Circuit

and seven others despite the absence of clear statutory language

so requiring. The new remedies provided in § 102 of the 1991 Act

merely expand the remedies available to federal employees under

s

Title VII, and their application to pending cases presents no

sovereign immunity concerns not presented by the broader change

in 1972 which created the cause of action.

The decision of this and other circuits to apply the 1972

amendments retroactively is consistent with the decisions of the

Supreme Court and this Circuit in determining the scope of Title

VII's waiver of sovereign immunity in other contexts. In Irwin

v. Veterans Admin.. Ill S. Ct. 453 (1990), the Supreme Court has

recognized that the canon that waivers of immunity must be

"unequivocally expressed" is inapplicable in determining whether

the broad waiver of sovereign immunity contained in Title VII

applies to a particular set of circumstances.

Moreover, this rule is simply the application to Title VII

of the more general rule, recently restated by the Supreme Court,

that a waiver of sovereign immunity "over certain subject matter"

renders inapplicable the canon requiring unequivocal expressions

of intent in determining the scope of that "subject matter"

waiver.

4

Second, contrary to the opinion of the District Court, the

statutory requirement that federal Title VII plaintiffs first

invoke administrative remedies is essentially the same as the

requirement for private plaintiffs. In both cases, the statute

simply requires that claimants notify their employer of their

claims to give the employer the opportunity to resolve them

without litigation, and that they wait at least 180 days prior to

suing. Neither federal nor private employees are required to

await the conclusion of the administrative process, and both are

entitled to a trial de novo in federal court. Also, contrary to

the opinion of the district court, allowing federal Title VII

plaintiffs in pending cases to add compensatory damage claims and

to have a jury trial will not undermine the statutory requirement

for invocation of the administrative process or impermissibly

deprive the United States of its opportunity to resolve such

claims at the administrative level.

Third, since Bowen v. Georgetown Univ. Hosp., 488 U.S. 204

(1988), the Government has urged on many occasions the continued

validity of the presumption of retroactivity in Bradley in

seeking to have various statutes applied to pending cases. This

compels the conclusion that the Government's advocacy before the

District Court of the rule in Bowen is the product of pragmatic

concerns rather than a principled analysis of the case law on

retroactive application of statutes.

5

ARGUMENT

I. The Canon of Construction That Waivers

of Sovereign Immunity Must Be Clearly

Expressed Does Not Require That the Text

of the 1991 Act State Explicitly That

$ 102 Applies to Pending Cases.__________

Congress in § 102 unmistakably waived the Government's

immunity to claims for compensatory damages and jury trial by

federal employee victims of intentional discrimination. The

question here is whether that waiver applies to claims that were

pending in court on the date of the statute's enactment. We

believe appellant has shown that the plain language of the 1991

Act unequivocally waives the Government's immunity as to pending

cases. Appellant's Br. 7-18. However, assuming that some ambi

guity exists, we show below that the canon requiring unequivocal

waivers of sovereign immunity is no bar to application of the

1991 Act to cases pending at the time of its enactment.

The Supreme Court has often stated that waivers of sovereign

immunity must be "unequivocally expressed." See, e.q., United

States Dep't of Energy v. Ohio, 112 S. Ct. 1627, 1633 (1992);

United States v. Nordic Village, Inc.. 112 S. Ct. 1011, 1014

(1992). The Government relied on this canon of construction

below in arguing that Van Meter should not be allowed to amend

his complaint to include claims for compensatory damages and a

jury trial.-7 Judge Gesell did not cite this principle in

See Defendant's Memorandum in Opposition to Plaintiff's

Motion To File Second Amended Complaint at 7, 10 n.4 (Nov. 27,

1991), Van Meter v. Barr, No. 91-0027 (GAG) (D.D.C.), citing

United States v. Mottaz. 476 U.S. 834, 851 (1986). J.A. 79, 85,

88 n.4.

6

refusing to apply § 102 to this case, relying instead on the pre

sumption against retroactivity in Bowen v. Georgetown Univ.

Hoso.. 488 U.S. 204 (1988), and Wagner Seed Co. v. Bush. 946 F.2d

918, 929 (D.C. Cir. 1991). 778 F. Supp. at 84-85, J.A. 231-32.

The Eighth Circuit, however, recently cited the "policy requiring

that waivers of sovereign immunity be strictly construed in favor

of the United States" to support its conclusion that § 114 of the

1991 Act, providing interest on awards under Title VII, does not

apply to federal employee cases pending on its effective date.

Huev v. Sullivan. No. 91-2908WM, 1992 U.S. App. LEXIS 11303, at

*9 (8th Cir., May 21, 1992). Accordingly, because we believe

that the Government's argument below and the Eighth Circuit's

conclusion in Huev were erroneous, we address the applicability

of the "clear expression" canon to Van Meter's case.

We show first that this Court and seven other Circuits have

held the provision authorizing federal employees to sue on their

discrimination claims, § 717 of Title VII, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16,

applicable to cases pending at the time of its enactment in 1972

despite the lack of an unequivocal waiver of sovereign immunity

as to those pending claims; and that those rulings warrant the

same conclusion here. We then show that this approach is con

sistent with the rulings of the Supreme Court and other rulings

of this Circuit determining the scope of Title VII's waiver of

the sovereign immunity of the United States. Finally, we show

that these Title VII rulings are applications of a more general

rule that, as most recently restated by the Supreme Court, the

7

canon requiring waivers of sovereign immunity to be clearly

expressed does not apply where the issue is whether an express

waiver over a particular subject matter covers a particular set

of circumstances.

A. This Court and Seven Other Circuits Have

Applied § 717 of Title VII to Pending Cases

Despite the Absence of an Unequivocal Waiver

of Sovereign Immunity as to Such Claims and

those Decisions Warrant the Same Result Here.

This Court has already determined that the canon requiring

that waivers of sovereign immunity be unequivocally expressed

does not bar the application of new remedies in federal employee

discrimination cases already pending. Womack v. Lynn. 504 F.2d

267 (D.C. Cir. 1974), held that the 1972 amendments to the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, which gave federal employees the opportunity

to sue in federal court by adding § 717 to Title VII, applied to

cases that had completed the administrative process and were

pending in the district court at the time those amendments became

effective, even though the 1972 Act did not expressly so pro

vide. - Id. at 269 & n.6. This Court found that § 717 merely

The Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972, which, inter

alia, added § 717 to Title VII, specifically provided: "The

amendments made by this Act to section 706 of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964 [right of action by private employees] shall be

applicable with respect to charges pending with the Commission on

the date of enactment of this Act and all charges filed there

after." Pub. L. No. 92-261, § 14, 86 Stat. 112, 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e-5 note (1988). This provision makes no reference to the

provision of the 1972 Act that added § 717 to Title VII and thus

does not expressly make § 717 applicable to pending claims. Nor

did any other provision of the 1972 Act do so.

8

provided a new remedy for a longstanding right of federal

employees to be free from discrimination. Id.

In so ruling, the Court adopted the reasoning of Roger v.

Ball. 497 F.2d 702 (1974), in which the Fourth Circuit explicitly

rejected sovereign immunity as a ground for applying the 1972

amendments prospectively only. Womack. 504 F.2d at 269. The

Court in Roger found no need for an explicit statement that the

new remedies applied to pending cases in light of Congress' clear

consent to suits by government employees to redress discrimina

tion. Roger. 497 F.2d at 708.^

With one exception, every other Circuit to consider the

applicability of § 717 to pending cases reached the same con

clusion as Womack and Roger. See Brown v. General Services

Admin.. 507 F.2d 1300, 1305-06 (2d Cir. 1974) (applying statute

to claims pending before administrative agency at time of § 717's

enactment), aff'd on other grounds. 425 U.S. 820 (1976)-;;

Sperling v. United States. 515 F.2d 465, 473-74 (3d Cir. 1975)

(same; "Whatever little may be said in support of a rule of

strict construction of waivers of sovereign immunity in new

fields, nothing can be said in favor of strict construction of a

11 Unlike Womack (and this case), in which the administrative

process had been completed, in Roger the employee was still in

the administrative process at the time the 1972 amendments became

effective. Roger. 497 F.2d at 704.

- 1 The Supreme Court in Brown explicitly took note of the Second

Circuit's holding that the 1972 amendments applied retroactively,

observing that "[t]he parties have apparently acquiesced in this

holding by the Court of Appeals, and we have no occasion to

disturb it." 425 U.S. at 824-25 & n.4.

9

waiver in a field where it has long existed."); Eastland v.

Tennessee Valiev Auth.. 553 F.2d 364, 367 (5th Cir. 1977) (same

as Brown); Adams v. Brinegar, 521 F.2d 129 (7th Cir. 1975)

(same); Mahroom v. Hook. 563 F.2d 1369, 1373 (9th Cir. 1977)

(same); Weahkee v. Powell. 532 F.2d 727, 729 (10th Cir. 1976)

(1972 amendment "applies to charges pending and unresolved on its

effective date")

The one exception was the Sixth Circuit, which relied on a

general presumption against applying statutes retroactively, as

well as sovereign immunity concerns, in limiting the application

of § 717 to cases filed after its enactment. Place v.

Weinberger. 497 F.2d 412 (6th Cir. 1974). However, in response

to a petition for rehearing of the Supreme Court's denial of

certiorari in that case, the Solicitor General confessed error,

and stated that he "had now concluded that section 717 applied to

all cases pending administratively on the act's effective date,

and represented to the court that the Government would refrain

from asserting any contrary views in all pending and future

cases."-/ The Court then granted the petition for certiorari,

- Other Circuits have relied on Womack, Roger and similar cases

in applying retroactively other statutory provisions which waive

the sovereign immunity of the United States for employment

discrimination claims. See, e.g.. Bunch v. United States, 548

F.2d 336, 340 (9th Cir. 1977) (amendments to the Age

Discrimination in Employment Act).

- 1 Adams v. Brinegar. 521 F.2d 129, 131 (7th Cir. 1975)

(summarizing United States' Memorandum in Response to Petition

for Rehearing, Place v. Weinberger, 426 U.S. 932 (1976) (No. 74-

116)) .

10

vacated the judgment, and remanded the case to the Sixth Circuit

for further consideration. 426 U.S. 932 (1976).

More recently, in Thompson v. Sawyer. 678 F.2d 257 (D.C.

Cir. 1982), this Court reaffirmed that sovereign immunity con

cerns are not an obstacle to the retroactive application of

§ 717. Thompson held that back pay in a federal employee Title

VII case may be awarded for the full two-year period provided in

§ 706(g), even when that period extends back prior to the effec

tive date of § 717. 678 F.2d at 287-90. In so ruling, the Court

rejected the Government's sovereign immunity arguments against

retrospective liability in a footnote saying, "the problem we

face is not whether Congress waived immunity, but whether the

waiver was prospective only." Id. at 289 n.33. The Court then

applied Bradley in resolving the retroactivity issue, rather than

the canon that waivers of sovereign immunity must be unequivo

cally expressed. - 1

In sum, this Circuit in Womack and Thompson rejected

sovereign immunity concerns as a reason for refusing to apply the

new cause of action created by § 717 of the 1972 Act to pending

cases. Adding § 717 to Title VII constituted a broad waiver of

the government's sovereign immunity from suits by federal

employees for employment discrimination. By contrast, the

statute at issue here, § 102 of the 1991 Act, merely makes new

The Court in Thompson also concluded that the 1974 amendments

to the Fair Labor Standards Act, which made that Act and thus the

Equal Pay Act applicable to federal employees, applied retro

actively, in spite of the absence of clear language to that

effect. 678 F.2d at 280-81 & n.23.

11

remedies of compensatory damages and a jury trial available in

such actions. Because of the lesser impact of the waiver in

§ 102, this case presents lesser, not greater, concerns for

sovereign immunity than were present in Womack. Accordingly,

this Court should reject sovereign immunity as a reason for

applying § 102 prospectively only.-;

B. Congress' Broad Waiver of Federal Immunity in

Title VII Makes It Inappropriate To Require

an Unequivocal Expression of Every Circum-

stance to Which It Extends.___________________

The soundness of Womack. Thompson, and the other cases

applying § 717 to pending cases absent express language to that

effect is confirmed by the decisions of the Supreme Court and

this Circuit construing the scope of Title VII's waiver of the

Government's sovereign immunity. These decisions hold that Title

VII's broad waiver of immunity satisfies the canon requiring

unequivocal waivers of sovereign immunity with regard to particu

lar circumstances not mentioned in the waiver. They demonstrate

that sovereign immunity concerns present no obstacle to the

retroactive application of the 1991 Act in this case.

See Lee v. Sullivan. No. C-89-2873, 1992 U.S. Dist. LEXIS

3616, at *44-45 (N.D. Cal. Mar. 26, 1992), (rejecting argument

that sovereign immunity concerns require that all doubts about

retroactive application of 1991 Act be resolved in Government's

favor and applying § 102's compensatory damages and jury trial

provisions to pending cases; quoting Campbell v. United States,

809 F .2d 563, 577 (9th Cir. 1987): "'the principle of sovereign

immunity does not require us to resolve all doubtful questions

concerning the temporal applicability of a statute in the

government's favor when the literal requirements of the statute

are otherwise met'").

12

In Irwin v. Veterans Admin.■ 111 S. Ct. 453 (1990), the

Supreme Court applied § 717's broad waiver of governmental

immunity beyond its explicit language despite the canon that

waivers of sovereign immunity must be unequivocally expressed.

Irwin involved a discrimination suit by a federal government

employee under § 717 of the 1964 Act. Irwin sought to have the

rule of equitable tolling applied to excuse her failure to file

suit within 30 days of her attorney's receipt of notice of the

agency's final decision as required by § 717(c), 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e-16(c). That time requirement, the Court noted, was a

"condition of [the Government's] waiver of sovereign immunity."

Ill S. Ct. at 456.

Although noting that in general a waiver of sovereign

immunity "cannot be implied but must be unequivocally expressed,"

the Supreme Court in Irwin recognized that that canon had no

further application where Congress had waived its immunity for

federal employment discrimination suits brought within the time

limitations of § 717(c), and the limited question before it was

whether that waiver encompassed the doctrine of equitable

tolling. In holding equitable tolling applicable to federal

employee suits, the Court said:

"Once Congress has made such a waiver, we

think that making the rule of equitable

tolling applicable to suits against the

Government, in the same way that it is

applicable to private suits, amounts to

little, if any, broadening of the con

gressional waiver. Such a principle is

likely to be a realistic assessment of

legislative intent as well as a practically

13

useful principle of interpretation."

Ill S. Ct. at 457.

Thus, the Court concluded that the filing deadline "condition" on

Title VII's waiver of immunity reasonably ought to be read to

tolerate the equitable tolling rule applicable to suits by

private employees.^

This Court anticipated the result in Irwin in Mondy v. Seely

of the Army. 845 F.2d 1051, 1055-57 (D.C. Cir. 1988), and Coles

v. Penny, 531 F.2d 609, 614-15 (D.C. Cir. 1976). In these cases,

this Circuit employed the standard tools of statutory construc

tion, looking to Title VII's structure and purposes, to determine

the scope of the Government's liability, rather than limiting

that statute to the "unequivocal expressions" of its text.

Although neither Mondv nor Coles explicitly relies on Title

VII•s broad waiver of governmental immunity to justify their

disregard of the "unequivocal expression" canon, that rationale

was suggested by the Court in Hacklev v. Roudebush, 520 F.2d 108

(D.C. Cir. 1975), which held that federal employees were entitled

to a trial de novo of their discrimination claims against the

Government, even if § 717's waiver of sovereign immunity was con

strued to be ambiguous on this point:

"A broad interpretation of § 717 is parti

cularly appropriate in light of the remedial

W similarly, in a non-Title VII case, Bowen v. City of New

York. 476 U.S. 467, 479-82 (1986), the Supreme Court held the 60-

day limit for seeking court review of a disability determination

by the Social Security Administration to be subject to tradi

tional equitable tolling principles despite the lack of explicit

reference to this rule in the statute waiving the Government's

immunity.

14

character of the 1974 [sic] amendments and

the constitutional overtones of the rights

protected through Title VII. And although it

is sometimes asserted that waivers of sover

eign immunity are to be strictly construed,

this principle generally relates to the cir

cumstances under which a court may entertain

a case rather than the essential characteris

tics of the case once it is properly enter

tained. No one asserts that Title VII cases

are not judicially cognizable because of

sovereign immunity; the controversy instead

rages over the issue of what rights Congress

intended to accord a federal litigant who is

properly before the District Court." Id. at

122 n . 5 3 . — ;

Library of Congress v. Shaw. 478 U.S. 310 (1986), decided

prior to Irwin, is not to the contrary. In that case, the Court

held that the broad waiver of sovereign immunity in Title VII did

not apply to interest on attorneys1 fees, relying on the long

standing requirement of express consent to awards of interest

against the Government:

"In the absence of express congressional

consent to the award of interest separate

from a general waiver of immunity to suit,

the United States is immune from an interest

award." Id. at 314.

While the Court said generally that courts must construe

waivers of sovereign immunity "strictly in favor of the sover

eign," 478 U.S. at 318, its opinion was based on the special rule

about interest. The Court explained that this rule "reflects the

Hacklev was cited with approval in Chandler v. Roudebush, 425

U.S. 840, 847 n.7, 848 (1976), which held that federal employees

were entitled to a district court trial de novo of their Title

VII claims without mentioning the canon that waivers of sovereign

immunity must be unequivocally expressed, or suggesting that this

canon was relevant in any way in determining the procedures by

which employment discrimination claims against the Government

were to be adjudicated.

15

historical view that interest is an element of damages separate

from damages on the substantive claim." Id. at 314. It went on

to say that the purpose of the rule "is to permit the Government

to 'occupy an apparently favored position,' by protecting it from

claims for interest that would prevail against private parties."

Id. at 315-16 (citation omitted). Thus, Shaw applies a particu

lar rule about waivers of sovereign immunity for interest, rather

than the general canon that "unequivocal expressions" are always

required.

Shaw did not raise any question about the Court's prior

handling of issues respecting § 717 in Brown v. GSA, supra, or

Chandler v. Roudebush. supra, where the Court said nothing about

a requirement of "unequivocal expression." Thus, Shaw should not

be read as requiring that every application of § 717 be "unequi

vocally expressed" in the statute. Moreover, Irwin, which came

after Shaw, did not so read it.

As Irwin and this Circuit's decisions have shown, the

"unequivocal expression" canon does not apply to all questions of

the scope of the waiver in § 717 of Title VII and should not

apply to this case.

C. Recent Supreme Court Cases Not Involving

Title VII Reaffirm That the Canon Requiring

Waivers To Be "Unequivocally Expressed" Is

Satisfied Where Congress Has Waived Immunity

Over a Certain Subject Matter._______________

in Ardestani v. INS, 112 S. Ct. 515 (1991), the Supreme

Court restated the rule regarding construction of the scope of a

statute waiving sovereign immunity:

16

"[0]nce Congress has waived sovereign

immunity over certain subject matter, the

Court should be careful not to 'assume the

authority to narrow the waiver that Congress

intended.'" Id. at 520 (guoting United

States v. Kubrick, 444 U.S. Ill, 118 (1979)

(construing Federal Tort Claims Act)).

Ardestani involved the question whether the Equal Access to

Justice Act, 5 U.S.C. § 504 and 28 U.S.C. § 2412 (1988) ("EAJA"),

making attorneys' fees available in certain adversary pro

ceedings, applied to deportation proceedings. Finding depor

tation proceedings to be "wholly outside the scope of the EAJA,"

112 S. Ct. at 520, the Court concluded that there was no general

subject matter waiver that could be construed to cover such

proceedings.

The Court cited with approval Irwin and Sullivan v. Hudson,

490 U.S. 877 (1989), another EAJA case, in which it applied the

EAJA's waiver of immunity beyond the statute's explicit terms.

Ardestani, 112 S. Ct. at 520-21. The question in Sullivan was

whether the EAJA's allowance of attorneys' fees for "civil

actions" extended to a non-adversarial benefits proceeding

required on remand from a reviewing court. Despite the lack of

explicit statutory language, the Court found that these benefit

proceedings were "an integral part of the 'civil action' for

judicial review" under the EAJA, and so eligible for attorneys'

fees. 490 U.S. at 892. The Court placed significant weight on

the EAJA's purpose "'to diminish the deterrent effect of seeking

review of, or defending against, governmental action,' 94 Stat.

2325." 490 U.S. at 890.

17

Although the Supreme Court in a recent case concerning the

Bankruptcy Code acknowledged the canon that waivers of sovereign

immunity must be "unequivocally expressed," the Court cited

Ardestani with approval. United States v. Nordic Village, Inc.,

112 S. Ct. 1011, 1015 (1992). Thus, the state of the law remains

that a general waiver of immunity "over certain subject matter"

means that every application of the waiver need not be unequivo

cally expressed.

II. Application of § 102 of the 1991 Civil

Rights Act to Federal Employee Cases

Pending in Court Does Not Undermine

Title VII's Requirement That Administra-

tive Remedies Be Invoked Before Suit.

The District Court found that the "overall structure of the

federal discrimination statutes" supports the conclusion that

§ 102 of the 1991 Act should not apply in cases pending on the

date of enactment. 778 F. Supp. at 85. First, the Court drew a

sharp contrast between the condition upon the right to sue for

private (and state) employees and the condition for federal

employees:

"Unlike private Title VII discrimination

cases, which may be brought directly into the

United States District Court irrespective of

whether or not the plaintiff has first

pursued administrative remedies with the

employer, see Johnson v. Greater Southeast

Community Hospital Corp., [951 F.2d 1268,

1276 (D.C. Cir. 1991)], in Title VII cases

against the federal government, the United

States has conditioned the waiver of its

sovereign immunity on the requirement that

the plaintiff first raise his or her dis

crimination grievances with the agency." Id.,

18

Accordingly, the Court said,

11 to allow Title VII plaintiffs simply to tack

claims for compensatory damages onto com

plaints already pending in U.S. District

Courts would, as a practical matter, deprive

the United States of its opportunity to

resolve claims for monetary damages at the

administrative level, and would, as a legal

matter, impermissibly broaden the juris

diction of the federal courts to include

claims that, contrary to the limited scope of

the federal government's waiver of sovereign

immunity in this area, had not followed the

administrative track still required by Title

VII as a prerequisite to judicial action in

federal employment cases." Id.

As we demonstrate below, the Court's sharp distinction

between the conditions applicable to private and federal

employees is illusory. Furthermore, allowing Title VII plain

tiffs to add compensatory damages claims to complaints already

pending in court would not deprive the United States of the

opportunity to settle cases without a trial nor render the

administrative process meaningless. In short, the impact on the

administrative process does not justify the Court's refusal to

apply § 102 of the 1991 Act to pending federal claims.

A. The Conditions on the Right To Sue for

Federal and Private Employees Are Essentially

the Same. ______ __________ ____ _______________

Title VII places similar conditions on federal and private

employees' rights to sue. The statute simply requires that both

notify their employer of their claims to give the employer the

opportunity to resolve the matter without litigation, and that

they wait at least 180 days before suing. Neither federal nor

private sector employees are required to await completion of any

19

employer or agency processes prior to filing suit, and both

federal and private employees are entitled to a trial de novo in

federal court.

Specifically, § 717 of Title VII does not itself prescribe

any particular administrative procedures for discrimination

claims against federal agencies. Section 717(b), 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e-16(b), authorizes the EEOC to enforce Title VII "through

appropriate remedies" and to issue regulations to carry out its

responsibilities under the Act. And § 717(c), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-

16(c), simply authorizes a civil action by federal employees "as

provided in section 706" (governing private and state and local

government employees), within 30 days after receipt of notice of

final action taken by the employing agency or by the EEOC on

appeal from a decision of the employing agency,— ' or, if the

agency or EEOC has not ruled, 180 days after "the filing of the

initial charge" with the employing agency or the filing of an

appeal with the EEOC.— '

The EEOC regulations issued pursuant to § 717(b) detail the

administrative procedures available to a federal employee

claiming discrimination. 29 C.F.R. part 1613 (1991).— ' Under

12' section 114(1) of the Civil Rights Act of 1991 amended

§ 717(c) and extended the 30-day filing period to 90 days.

12' See 29 C.F.R. § 1613.281 (1991).

— ' The EEOC has recently amended the regulations governing

federal sector egual employment opportunity. 29 C.F.R. part

1614, published at 57 Fed. Reg. 12,634 (Apr. 10, 1992) (effective

Oct. 1, 1992) (superseding part 1613). The changes the new

regulations make in the administrative procedures are, for the

purposes of this case, insignificant.

20

those regulations, a federal employee who believes he or she has

been discriminated against must consult with an Equal Employment

Opportunity (EEO) Counselor of the employing agency within 30

days of the allegedly discriminatory event, its effective date,

or the date the event was or should have been discovered. 29

C.F.R. §§ 1613.213(a), -.214(a). If the matter is not informally

resolved through consultations with the EEO Counselor, the em

ployee has the right to file a written administrative complaint.

Id.

The administrative process commenced by this written com

plaint or "charge" may end quickly — as it did in this case —

when the employing agency rejects or cancels the complaint

without investigation or hearing for any of seven different

grounds set forth in 29 C.F.R. § 1613.215(a), such as a finding

that the complaint is untimely. Alternatively, the adminis

trative process may take a considerable amount of time, while,

after acceptance of the complaint, the claim is investigated; set

for hearing and recommended decision by an EEOC Administrative

Judge; decided by the head of the employing agency (or a desig

nee) ; and, at the employee's option, appealed to the EEOC. See

29 C.F.R. §§ 1613.216-.221, .231. In either event, the em

ployee's right to sue accrues no later than 180 days after the

filing of the complaint or an appeal to the EEOC. 29 C.F.R.

§ 1613.281. Moreover, the employee has the right to de novo,

consideration of his or her claims in federal court whatever the

21 -

outcome of the administrative process. Chandler v. Roudebush,

425 U.S. 840, 861 (1976).

Federal employees thus have rights in the administrative

process that private employees do not have: the right to a full

administrative hearing, followed by a decision by the agency

head, and the right to appeal an adverse agency decision to the

EEOC. But they are not obliged to await completion of or to

"exhaust" that process, and if they do wait for its completion,

they are not bound by an adverse result . —11 If 180 days goes by

without a final agency decision, they are free to bring suit in

federal court; and if a decision comes down sooner (or if they

decide to wait for a decision), they are free to start over again

in federal court.

With respect to the administrative processes they are

required to invoke, federal employees are in essentially the same

position as private employees. Private employees with claims of

discrimination are required by § 706 of the 1964 Civil Rights Act

to file a "charge" with the State or local fair employment prac

tice agency (where there is one) and with the EEOC, within the

time periods specified in the statute. Both the Act and the

regulations require that the EEOC serve the charge upon the

complainant's employer. § 706(b), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e—5(b); 29

C.F.R. § 1601.14(a). If the Commission determines after investi-

15/ m Grubbs v. Butz. 514 F.2d 1323, 1327-28 (D.C. Cir. 1975),

this Court specifically declined to go beyond the language of the

statute and add a requirement that federal employee plaintiffs

complete the administrative process before suing or proceeding

with an already-instituted suit.

22

gation that there is reasonable cause to believe that the alleged

discrimination occurred, the Commission is required to attempt to

resolve the matter informally, through "conference, conciliation,

and persuasion." § 706(b), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(b). Like the

federal employee, the private employee is not required to await

completion of that process. Within 180 days after the charge is

filed — the same period that the federal employee must wait —

the private employee may request and the Commission must promptly

issue a notice of right to sue. 29 C.F.R. § 1601.28(a)(1).

After receipt of that notice, the private employee may sue in

federal court. § 706(f)(1), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e~5(f)(1). Simi

larly, if the EEOC dismisses the charge for any reason, it must

issue a notice of right to sue. 29 C.F.R. § 1601.18(e).

In short, in each instance, the purpose of the statutory

requirement is to give the employee and the employer the oppor

tunity to resolve the matter informally, without the necessity of

a lawsuit. As this Court said in Manqiapane v. Adams, 661 F.2d

1388 (D.C. Cir. 1981), a federal employee case, "[t]he only ex

haustion requirement expressly made by Title VII is the em

ployee's duty to 'first complain to his employing agency * * *.'"

Id. at 1390 (citation omitted). While the federal employee files

a complaint with his or her employing agency and the private

employee files a charge with the EEOC, in each case the employer

is to be notified of the claim and given the opportunity to

resolve the matter informally.

23

The District Court found it significant that private Title

VII cases may be brought "irrespective of whether or not the

plaintiff has first pursued administrative remedies with the

employer." 778 F. Supp. at 85, citing Johnson v. Greater

Southeast Community Ho s p . Coro.. 951 F.2d 1268 (D.C. Cir. 1991).

But there is no significance in that difference. Private

employees are not required by Title VII to go through whatever

procedures the private employer may require of its employees, but

they are required to notify the employer of their claims by

filing a charge with the EEOC. That requirement may lead to

conciliation efforts by the EEOC. At the very least, it affords

the employer an opportunity to settle the matter during the 180-

day waiting period before suit may be filed. Similarly, federal

employees must notify the employing agency of their claims by

filing a written complaint, but they are not required to await

the conclusion of that process. It is true that the applicable

regulations require the employing federal agency to investigate

the claims and propose a disposition — an obligation not placed

on private employers —— but the essential purpose of the written

complaint is to afford the employing agency the opportunity to

settle the matter without substantially burdening the federal

employee.

Thus, the conditions imposed by Title VII upon private and

federal employees' right to sue are essentially the same, and the

District Court erred in placing weight on the insignificant

differences that exist as a ground for concluding that applica-

24

tion of § 102's remedies in pending cases would somehow compro

mise the statutory provisions for invocation of the administra

tive process by federal employees.

B. Allowing Federal Title VII Plaintiffs To Add

Compensatory Damage Claims and To Have a Jury

Trial in Court Will Not Undermine the Requirement

That Federal Employees Invoke Administrative

Remedies Before Suit.______________________________

Contrary to the District Court's opinion, allowing Title VII

plaintiffs to add compensatory damages claims in court, with the

related right to jury trial, will not undermine the requirement

that federal employees invoke administrative remedies before suit

and impermissibly "deprive the United States of its opportunity

to resolve claims for monetary damages at the administrative

level." 778 F. Supp. at 85.

The purpose of this statutory requirement, as just ex

plained, is to give the federal employee and the employing agency

the opportunity to resolve their dispute without a lawsuit. As

we show below, federal employees with suits in federal court may

have had any of a number of different experiences in the adminis

trative process, but in no event will the conciliatory purpose of

the statutory requirement be undermined by allowing such

employees to seek compensatory damages remedies in the district

court that were not available and thus not considered during the

administrative process.

Some employees, like Van Meter, will have had their adminis

trative claims dismissed as untimely. In such cases, the

employing agency will have elected to forego the opportunity to

25

resolve the claim on the merits at the administrative level, and

there is no good reason to think that an earlier change in the

nature of recoverable damages would have had any effect on the

process.

Other employees will have elected to go to court after 180

days rather than waiting for the agency to complete its investi

gation, or will have allowed their case to go through administra

tive hearing and decision and will have sued because they were

dissatisfied with the result (on liability or on remedy). In

either situation, the agency will have had an opportunity to

resolve the claim at the administrative level; it will continue

to have the opportunity to settle the case after the complaint is

filed in court. While the employing agency may have made a

higher offer initially, had the 1991 Act been in effect while the

case was in the administrative process, nothing prevents the

employing agency from making that higher offer after the com

plaint is filed in court . —'1

Thus, in each of the circumstances in which a federal

employee will have properly invoked the administrative process,

the agency's interest in having an opportunity to resolve the

When the case has gone through a complete administrative

hearing, the government (and the employee) will have benefitted

in other ways as well. The broad discovery required by or

permitted in the administrative process, 29 C.F.R. § 1613.216,

.218, may make discovery in the lawsuit unnecessary. At the very

least, it will have reduced the scope of court-related discovery.

The EEOC's amended rules for resolution of federal employees'

discrimination claims, which become effective on October 1, 1992,

significantly expand the powers of the administrative judge to

order discovery. 29 C.F.R. § 1614.109(b), 57 Fed. Reg. 12,634,

12,650 (Apr. 10, 1992).

26

matter without a lawsuit will have been satisfied, even where new

remedies become available while the lawsuit is pending.

Cases in this Circuit support the notion that § 717's

requirement for invocation of the administrative process should

be given a practical reading that does not deprive federal

employees of new remedies for employment discrimination. In

Womack v. Lynn, 504 F.2d 267 (D.C. Cir. 1974), this Court per

mitted a federal employee plaintiff to amend a complaint filed

prior to 1972 to add a count based on the newly-enacted § 717.

Since the complaint, as originally filed, had been based on a

number of dubious causes of action,— 7 the Court's ruling

implicitly rejected any notion that the Government was improperly

prejudiced because, at the time plaintiff was pursuing the then-

existing administrative remedies, the Government's assessment of

the potential strength of the claim must have been very different

from its assessment after the 1972 amendments. As the Court

said, "Section 717(c) is merely a procedural statute that affects

the remedies available to federal employees suffering from

employment discrimination." 504 F.2d at 269 (emphasis in

original). The same is true in this case, and any contention by

the Government that it was unreasonably prejudiced because of its

— 7 Womack claimed the right to sue under the Fifth Amendment to

the Constitution; the Administrative Procedure Act, 5 U.S.C.

§ 701 et sea. (1970); the Back Pay Act, 5 U.S.C. § 5596 (1970);

28 U.S.C. § 2201 (1970); 42 U.S.C. § 1981 (1970); and Executive

Orders 11246, 3 C.F.R. 339 (1964-1965), and 11478, 3 C.F.R. 803

(1966-1970). 504 F.2d at 268 n.2.

27

view of the case during the administrative process should be

similarly rejected.— ''

The Court again took a practical view of the requirement

that federal employees invoke the administrative process prior to

suit in President v. Vance, 627 F.2d 353 (D.C. Cir. 1980).

There, plaintiff's administrative complaint had not specified a

particular promotion as part of the relief he sought. This Court

rejected the Government's argument that this failure barred

plaintiff from pursuing that relief in court, saying: "We think

so strict a requirement would impose far too heavy a burden upon

a lay complainant, and far too little responsibility on the

agency, particularly one that has admitted its own wrongdoing."

627 F .2d at 361. Later in the opinion, the Court elaborated

further on the theme that the requirement of prior resort to

administrative remedies should not stand in the way of full

relief to victims of discrimination by the federal government:

"[The requirement that claimants invoke

administrative remedies prior to suit] is not

an end in itself; it is a practical and

pragmatic doctrine that 'must be tailored to

fit the peculiarities of the administrative

— / m Bunch v. United States. 548 F.2d 336 (9th Cir. 1977), the

Court of Appeals relied on Womack in holding that the 1974

amendment to the Age Discrimination Employment Act (ADEA), which

made the ADEA applicable to federal employees, should be applied

to federal employee cases pending at the time of the amendment.

In doing so, the Court expressly rejected the Government's

argument that it should dismiss a claim "for failure to exhaust

administrative remedies that were nonexistent at the time he

sought relief from the federal court." 548 F.2d at 340. As the

court pointed out, "The ADEA amendments, like the 1972 Title VII

amendments, did not create new substantive rights, but simply

created new procedures and remedies for the vindication of pre

existing discrimination claims." Id. at 339.

28

system Congress has created.1 Exhaustion

under Title VII, like other procedural

devices, should never be allowed to become so

formidable a demand that it obscures the

clear congressional purpose of 'rooting out

. . . every vestige of employment discrim

ination within the federal government.'" Id.

at 363 (footnote omitted).

These cases show that Title VII's requirement that federal

employees invoke the administrative process before suit should

not bar them from the remedies provided by § 102. In all of the

cases pending in district court in which plaintiffs have properly

invoked the administrative process before suing, their employing

agencies will have received full notice of the nature of any

claim of discrimination, and will have had the opportunity to

resolve the claim before suit was filed. Denying these plain

tiffs full relief simply because the remedial law at the time

they pursued those remedies was less favorable to them — and

denied them the right to full compensatory relief — would be

contrary to long-standing law in this circuit and untrue to

Congress' limited purpose in delaying the right to sue until a

claim has been considered by the employing agency.

III. The United States Has Taken Conflicting

Positions on Retroactivity Issues Sub-

secruent to the Bowen Decision.______ _

Traditionally, courts view the United States not as "an

ordinary party to a controversy," but as a "servant of the law"

whose interest is "not that it shall win a case, but that justice

29

shall be done."— 7 Courts expect the United States to present

principled arguments on which they can rely for guidance.

With regard to the retroactivity of the Civil Rights Act of

1991, however, the Government has abandoned positions it has

advanced in numerous cases in favor of an analysis that appears

to be born more of pragmatism than of principle. Thus, in this

case, the Government argued that Bowen v. Georgetown Univ. Hosp.,

488 U.S. 204 (1988), and related cases establish a "heavy pre

sumption against retroactivity," and that Bradley v. School Bd.

of the City of Richmond. 416 U.S. 696 (1974), "constitute[s], at

best, an exception to the general rule favoring only prospective

application of statutes and amendments."— 7 This position is

contrary to the position the United States has advanced in

numerous briefs filed subseguent to the Bowen decision in

December 1988.— '

In a number of cases subsequent to Bowen, the Government has

referred to Bradley's presumption of retroactivity as a "well

settled,"— 7 "fundamental princip[le]. 7 The United States

^ Beraer v. United States. 295 U.S. 78, 88 (1935).

22' Defendant's Memorandum in Opposition to Plaintiff's Motion To

File Second Amended Complaint at 6, 16 (Nov. 27, 1991), Van Meter

v. Barr, Civ. No. 91-0027 (GAG) (D.D.C.), J.A. 79, 84, 94.

— 7 Excerpted pages from the Government briefs discussed in this

section are reproduced in a separate volume of Appendices to this

brief.

— 7 Brief of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation at 2 6

(argued Feb. 26, 1991), FDIC v. Wright, 942 F.2d 1089 (7th Cir.

1991) (No. 90-2217).

(footnote 23 on following page)23/

30

has distinguished Bowen, Bennett v. New Jersey, 470 U.S. 632

(1985), and related cases on which it relied below to support a

claimed presumption against retroactivity, and has urged courts

— / Brief for the United States at 23 (June 28, 1990), U.S. v.

Peppertree Apartments et al.. George Bailes, Jr., 942 F.2d 1555

(11th Cir. 1991) (No. 89-7850) ( "Bailes"). Defendant Bailes

filed a petition for certiorari on December 6, 1991. On April 1,

1992, the Solicitor General filed a memorandum stating that the

United States had "determined not to pursue its claim" for

damages under the new statute, and that Bailes' petition should

be granted and the decision of the Court of Appeals vacated as

moot. Memorandum for the United States, Bailes v. United States,

No. 91-1075, at 4 (U.S. Apr. 1, 1992). The Court entered the

order requested by the United States. 112 S. Ct. 1755 (1992).

However, while the United States renounced its claim for damages

in Bailes. the Solicitor General did not confess error, and the

United States remains free to argue for the retroactive

application of the newly enacted damages provision, 12 U.S.C.

§ 1715z-4a(c) (1988), in future cases.

For other post-Bowen briefs relying on Bradley1s presumption

of retroactivity, see Brief for the United States at 48 (July 1,

1991), U.S. v. Israel Discount Bank, Ltd., No. 91-5026 (11th

Cir.) ("IDB"); Respondent Immigration and Naturalization

Service's Opposition to a Stay of Deportation at 19, 21 (May 10,

1991), Avala-Chavez v. INS/ 945 F.2d 288 (9th Cir. 1991) (No. 91-