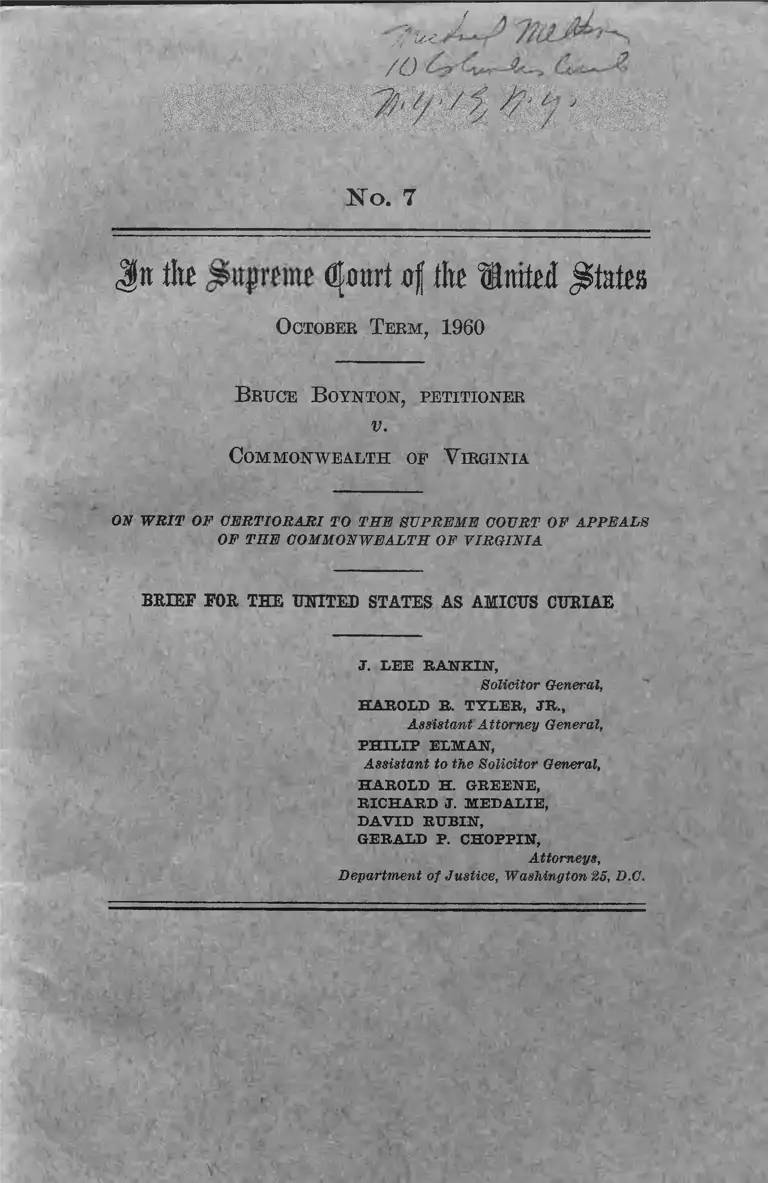

Boynton v. Virginia Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

August 8, 1960

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Boynton v. Virginia Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae, 1960. d1529b9c-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d0aa685d-8950-4681-89ca-48495aa7e812/boynton-v-virginia-brief-for-the-united-states-as-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

J> // / // [V-€

/£)

l o . 7

J tt tfe d|0urt 0f t o Wimtd S tates

October Term , 1960

B ruce B oynton, petitioner

v.

COMMONAVEALTH OF VIRGINIA

ON W R IT OF C E R T IO R A R I TO T H E SU P R E M E COURT OF A P P E A LS

OF T H E COM M ONW EALTH OF V IR G IN IA

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE

J. LEE R A N K IN ,

Solicitor General,

HAROLD R. TYLER, JH .,

A ssistan t A ttorney General,

P H IL IP ELMAN,

A ssistan t to the Solicitor General,

HAROLD H. GREENE,

RICHARD J. M EDALIE,

DAVID R U B IN ,

GERALD P. CHOPPIN,

A ttorneys,

Department of Justice, Washington 25, D.C.

I N D E X

i*ag«

Statement__________________ 1

Argument________________ 4

Point I______ 5

Point II____________________________ 9

Point III____________________________ 16

Conclusion_____________________ 28

Appendix___________________________________ 29

C ITA TIO N S

•Cases:

Air Terminal Services, Inc. v. Rentzel, 81 F.

Supp. 611_________________________ 20

American Federation of Labor v. Swing, 312

U.S. 321__________________________ 18

Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Ry. Co., 135

I.C.C. 633_________________________ 14

Atlantic Coast Line R. Co. v. North Carolina

Corp. Commission, 206 U.S. 1__________ 11

Augustus v. City of Pensacola, 1 R.R.L.R. 681 19

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249_________ 17

Bob-Lo Excursion Co. v. Michigan, 333 U.S.

28________________________________ 15

Boman v. Birmingham Transit Co,, decided

July 12, 1960_______________________ 26

Bridges v. California, 314 U.S. 252_________ 18

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483__ 20

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U.S. 296______ 18

Chance v. Lambeth, 186 F. 2d 879, certiorari

denied, 341 U.S. 941____________ _____ 10,11

City of Greensboro v. Simkins, 246 F. 2d 425__ 20

561431— 60-------1 ( l )

II

Cases—Continued

City of Petersburg v. Alsup, 238 F. 2d 830, Page

certiorari denied, 353 U.S. 922__________ 19

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3__________ 16,17, 21

Coke v. City of Atlanta, (N.D. Ga.)______ 20

Dayton Union Ry. Co. Tariff for Redcap Serv

ice, 256 I.C.C. 289___________________ 12

Debs In re, 158 U.S. 564________________ 11

Derrington v. Plummer, 240 F. 2d 922, cer

tiorari denied, 353 U.S. 924___ _________ 20

Draper v. City of St. Louis, 92 F. Supp. 546,

appeal dismissed, 186 F. 2d 307______ _ 19

Fay v. New York, 332 U.S. 261_______ ___ 27

Flemming v. South Carolina Electric & Gas Co.,

224 F. 2d 752, appeal dismissed, 351 U.S.

901_______________________________ 21

Freeman v. Retail Clerks Local 1207 (Kings

County Super. Ct., Washington), decided

December 9, 1959 (28 U.S.L. Week 2311).- 25

Gayle v. Browder, 352 U.S. 903___________ 20

Gibbons v. Ogden, 9 Wheat. 1___________9

Hall v. DeCuir, 95 U.S. 485_____________ 9

Hayes v. Crutcher, 137 F. Supp. 853_______ 19

Henderson v. United States, 339 U.S. 816____ 7,

10, 12,13,15

Henry v. Greenville Airport Commission, de

cided April 20, 1960__________________ 20

Holley v. City of Portsmouth, 150 F. Supp. 6__ 19

Holmes v. City of Atlanta, 350 U.S. 879, revers

ing 223 F. 2d 93_____________________ 19

Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U.S. 24______________ 27

Kansas City So. Ry. Co. v. Kaw Valley List.,

233 U.S. 75_________________________ 10

" Kerr v. Enoch Pratt Free Library, 149 F. 2d

212, certiorari denied, 326 U.S. 721_____ 21

in

Cases—Continued Page

Keys v. Carolina Coach Co., 64 M.C.C. 769.. 8

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214_____ 22

Kreshik v. St. Nicholas Cathedral, 363 U.S.

190_______________________________ 18

Lawrence v. Hancock, 76 F. Supp. 1004_____19, 20

Lonesome v. Maxwell, 220 F. 2d 386___________ 19

McCabe v. Atchison .T. & S.F.R. Co., 235 U.S. :

151----------------------------------------------- 19

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U.S. 501___ 5,17, 24,25, 26

Mayor and City Council of Baltimore v.

Dawson, 350 U.S. 877, affirming 220 F. 2d

386------------------------- ---------------------- 19

Mitchell v. United States, 313 U.S. 80______ 7,

10,13,15,19, 21

Moorhead v. City of Ft. Lauderdale, 152 F.

Supp. 131, affirmed, 248 F. 2d 544______ 19

Moorman v. Morgan, 285 S.W. 2d 146_____ 19

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U.S. 373____ 9, 10, 14,15

Morris v. Duby, 274 U.S. 135_____________ 11

Muir v. Louisville Park Theatrical Ass’n., 347

U.S. 971, reversing 202 F. 2d 275________ 19, 20

Munn v. Illinois, 94 U.S. 113______ ______ 24

N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama, 357 U.S. 449_______ 18

N.A.A.C.P. v. St. Louis-S.F. Ry. Co., 297

I.C.C. 335-------------------------------------- 12,15

Nash v. Air Terminal Services, 85 F. Supp. 545- 20

National Labor Relations Board v. Babcock &

Wilcox Co., 351 U.S. 105____ 24

New Orleans City Park Improvement Assoc, v.

Detiege, 358 U.S. 54, affirming, 252 F. 2d

122-------------------------------- 19

Philadelphia, B. & W.R. Co. v. Smith, 250

U.S. 101___ •_______________________ 11

Republic Aviation Corp. v. National Labor

Relations Board, 324 U.S. 793, n. 8_____ 24

IV

Cases—Continued Page

Rice v.Santa Fe Elevator Corp., 331 U.S. 218_ 12

St. Louis-S.F. Ry. v. Public Service Com

mission, 261 U.S. 369___________________ 11

Seaboard Air Line Ry. v. Blackwell, 244 U.S.

310_______________________________ 9

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1____ 5,17,18, 25, 27

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649____________ 26

Solomon v. Pennsylvania R.R., 96 F. Supp.

7 0 9 - ___ 9

South Covington Ry. v. Covington, 235 U.S. 537_ 10

Southern Pacific Co. v. Arizona, 325 U.S. 761 _ 9

Tale v. Department of Conservation, 133 F.

Supp. 53, affirmed, 231 F. 2d 615, certiorari

denied, 352 U.S. 838__________________ 20

Terry v. Adams, 345 U.S. 461____________ 26

Virginia v. Rives, 100 U.S. 313___________ 27

Ward v. City of Miami, 151 F. 593, affirmed,

252 F. 2d 787_______________________ 19

Whiteside v. Southern Bus Lines, 177 F. 2d 949- 10,11

Williams v. Carolina Coach Co., I l l F. Supp.

329, affirmed, 207 F. 2d 408____________ 8

Williams v. Howard Johnson’s Restaurant, 268

F. 2d 845__________________________ 13,14

Williams v. Kansas City, Mo., 104 F. Supp.

848, affirmed, 205 F. 2d 47, certiorari denied,

346 U.S. 826________________________ 19

Constitution and statutes:

United States Constitution:

Fourteenth Amendment. 15,16,17,18,19,20, 27

Art. I, Sec. 8, Cl. 3_________________ 9,11

Act of September 18, 1940, 54 Stat. 899___ 5

Civil Rights Act of 1866, 14 Stat. 27______ 23

Civil Rights Act of 1875, 18 Stat. 336_____ 23

Constitution and statutes—Continued

Interstate Commerce Act, 49 U.S.C. 1, et seq.:

National Transportation Policy (preced-

ing 49 U.S.C. 1)__________________ 5-6

49 U.S.C. 3(1)_____________________ 7,12

49 U.S.C. 16(13)___________________ 8

49 U.S.C. 303(a)(19)_______________ 7,9

49 U.S.C. 304(d)___________________ 8

49 U.S.C. 316(a)___________________ 6

49 U.S.C. 316(d)___________________ 6, 7

42 U.S.C. 1981____________________ 27, 28

42 U.S.C. 1982____________________ 27, 28

Miscellaneous:

Cong. Globe, 42d Cong., 2d Sess., pp. 381,

382-383____________________ 23

Cong. Record, 43d Cong., 1st Sess., p. 11._ 23

1 R.R.L.R. 681________________ 24

N.Y. Times, April 23, 1960, p. 21, col. 1.. 25

J n the £ttj?ttme flfottrt of the United States

October T erm , 1960

No. 7

B ruce B oynton, petitioner

v.

Commonwealth op V irginia

ON W R IT OF C E R T IO R A R I TO T H E SU PR E M E COURT OF A P P E A LS

OF TH E COM M ONW EALTH OF V IR G IN IA

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE

STA TEM EN T

At 8:00 p.m. on December 20, 1958, petitioner, a

Negro student in his third year at the Howard Uni

versity School of Law in Washington, D.C., boarded

a Trail ways bus in Washington to travel to his home

in Selma, Alabama (R. 27). He had in his possession

a ticket entitling him to travel to Montgomery, Ala

bama, on Trail ways (R. 27). The bus arrived at the

Trail ways Bus Terminal in Richmond, Virginia, at

about 10:40 p.m. When the driver pulled the bus

up to the stop at the terminal, he notified the passen

gers, including petitioner, that there would be a forty-

minute stopover (R. 28).

(i)

2

Because lie was hungry, petitioner alighted from

the bus and entered the terminal to get something to

eat (R. 28). He had never stopped in Richmond

before and did not know of any other place where

he could get something to eat within such a short time

(R. 29). There were two restaurants in the terminal.

One, which was “customarily used for colored people”

(R. 22), appeared to be crowded (R. 28). Petitioner

proceeded to the other restaurant, “customarily used

for * * * white” people (R. 22) which was not

crowded, and sat down upon one of the vacant stools

at the counter (R. 28).

One of the waitresses thereupon asked him to leave

and go over to the other restaurant (R. 28). He in

formed her that the other restaurant was somewhat

crowded and that he was an interstate passenger (R.

28). She insisted that, because of specific orders

which she had been given and also because of the

custom there, she could not serin him (R. 28). He

reminded her that he was an interstate passenger and

explained that, because his bus would be leaving

within a short time, he would like to get something

that would not take too long to prepare (R. 28). The

waitress suggested that he purchase a prepared sand

wich, whereupon he ordered one of the sandwiches

with a beverage (R. 29).

The waitress departed, and then returned and in

formed petitioner that she had orders not to serve

him (R. 29). He then asked her to find someone who

could serve him (R. 29). She departed again and

returned with the Assistant Manager of the restaurant

(R. 20, 29). The Assistant Manager told petitioner

3

that he could not be served (R. 29), explained that

there was a restaurant “ on the other side for the

colored” (R. 21), and suggested that he go to that

restaurant (R. 21). Petitioner refused and continued

to insist that his status as an interstate passenger

entitled him to be served (R. 29). The Assistant

Manager then called a police officer to enlist his aid

in getting petitioner to leave (R. 21). The officer

took petitioner outside and “tried to explain to him

the situation” (R. 21), and then returned and asked

the Assistant Manager if he wanted a warrant for

petitioner’s arrest (R. 21). After first replying in

the negative (R. 21), the Assistant Manager, upon

noticing that petitioner had returned, reconsidered

and caused petitioner to be arrested for trespassing

(R. 21, 29).

The bus terminal was owned and operated by

Trailways Bus Terminal, Inc. (R. 9). The restau

rants were built into the terminal upon its con

struction and leased by Trailways to Bus Terminal

Restaurant of Richmond, Inc. (R. 9-17). The lease

grants exclusive authority to the latter to operate

restaurants in the terminal (R. 10) and requires

that the restaurants be operated in keeping with

the character of service maintained in an up-to-date,

modern bus terminal (R. 14), that the lessee obtain

the lessor’s permission before selling any commodity

not usually sold or installed in a “bus terminal

concession” (R. 11), that the lessee refrain from sell

ing on buses operating in or out of the terminal, and

that, upon notice from the lessor, the lessee refrain

561431— 60----2

4

from making sales through the windows of the buses

(ft. 16). At no facility in the terminal, with the ex

ception of these restaurants, is racial segregation

required or practiced (R. 8).

Trial on the trespassing charge was held on Janu

ary 6, 1959, in the Police Court of the City of

Richmond (R. 19). At the conclusion of the pro

ceedings, petitioner was found guilty and fined $10

(R. 30). On February 20, 1959, the judgment was

approved by the Hustings Court of the City of

Richmond (R. 30-31). On June 19, 1959, the

Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia affirmed the

judgment of the Hustings Court (R. 32).

A RG UM EN T

During the course of his journey, petitioner, an

American citizen traveling from one state to another

on a federally-regulated carrier, was denied, solely be

cause of his race or color, the right to equal treat

ment in the use of an essential transportation facility -

in this instance, a restaurant in a bus terminal serving

interstate passengers. This denial was compounded by

the action of a state in prosecuting and punishing him

as a criminal trespasser. The invocation of the state’s

trespass law against petitioner for acts constituting a

peaceable and orderly attempt to exercise his federal

rights to equal treatment in the use of transportation

facilities while traveling on interstate carriers subject

to federal regulation had the necessary and inevitable

effect of thwarting and defeating these rights.

: This case does not involve purely private or individ

ual action which is in no respect enforced, implemented,

5

or supported by governmental authority. I t does not

present any question as to “ the right of a homeowner”

to choose or “to regulate the conduct of his guests”

{Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U.S. 501, 506), for the facili

ties with which we are concerned here were “built and

operated primarily to benefit the public” {ibid.). Nor

is this a case in which the state “has merely abstained

from action, leaving private individuals free to impose

such discriminations as they see fit.” Shelley v.

Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1, 19. On the contrary, the judg

ment here under review represents an affirmative exer

tion of governmental authority to sanction and consum

mate racial discrimination, thereby making the state

itself a party to the discrimination. In short, the sig

nificant aspects of this ease are its public, interstate,

and governmental action aspects.

I

The discrimination here against petitioner con

flicts both with the general purposes and objects of

the Interstate Commerce Act, 49 U.S.C. 1, et seq., as

embodied in the “National Transportation Policy,” 1

149 U.S.C. preceding Section 1, added to thej Interstate Com

merce Act by the Act of September 18, 1940, 54 Stat. 899. Seg

regation of interstate bus passengers by race in a bus terminal

restaurant is contrary to the “National Transportation Policy”

in almost every one of its particulars. That policy is as fol

lows: “I t is hereby declared to be the national transportation

policy of the Congress to provide for fair and impartial regu

lation of all modes of transportation subject to the provisions

of this Act, * * * so administered as to recognize and preserve

the inherent advantages of each; to promote safe, adequate, eco

nomical, and efficient service and foster sound economic

conditions in transportation and among the several carriers;

to encourage the establishment and mainilend/nce o f reasonable

6

and with several of the specific provisions of the Act,*

especially 49 U.S.C. 316(d).3 That subsection states

clearly that it “shall be unlawful * * * to subject any

charges for transportation services, without unjust discriminar

tions, undue preferences or advantages, or unfair or destruc

tive competitive practices; to cooperate with the several States

and the duly authorized officials thereof; and to encourage

fair wages and equitable working conditions; all to the end

of developing, coordinating and preserving a national trans

portation system by water, highway, and rail, as well as other

means, adequate to meet the needs of the commerce of the

United States, of the Postal Service, and of the national de

fense. All of the provisions of this Act shall be administered

and enforced with a view to carrying out the above declaration

of policy” (emphasis added).

2 For example, 49 U.S.C. 816(a) provides in pertinent part

that “[i]t shall be the duty of every common carrier of pas

sengers by motor vehicle * * * to provide * * * adequate serv

ice * * * and facilities for the transportation of passengers in

interstate or foreign commerce; to establish, observe, and en

force just and reasonable individual and joint rates, fares, and

charges, and just and reasonable regulations and practices re

lating thereto, and to * * * the facilities for transportation,

and all other matters relating to or connected with the trans

portation of passengers in interstate or foreign commerce

* * I t seems clear that a segregated dining facility is

foreign to the mandate, embodied in Section 316(a), that “ade

quate service and facilities” be maintained for all, including

Negro passengers. Similarly, the duty of enforcing “just and

reasonable regulations and practices” relating to transportation

facilities “and all other matters relating to or connected with

the transportation of passengers” clearly seems to be violated

by the practice of racial discrimination in the terminal facili

ties which the passengers must use.

3 49 U.S.C. 316(d) provides in pertinent part that “[a]ll

charges made for any service rendered or to be rendered by

any common carrier by motor vehicle engaged in interstate or

foreign commerce in the transportation of passengers or prop

erty as aforesaid or in connection therewith shall be just and

reasonable, and every unjust and unreasonable charge for such

service or any part thereof, is prohibited and declared to be

7

particular person * * * to any unjust discrimination

or any undue or unreasonable prejudice or disad

vantage in any respect whatsoever * * This

provision in Section 316(d), embodied in Part I I of

the Act dealing with “ Motor Carriers,” is identical to

the provision in 49 U.S.C. 3(1), embodied in P art I

of the Act dealing with “General Provisions and Rail

road and Pipe Line Carriers,” which was held in

Mitchell v. United States, 313 U.S. 80, and Henderson

v. United States, 339 U.S. 816, to proscribe racial dis

crimination in interstate railroad pullman and dining

cars. Under the Act, “racial classification of passen

gers holding identical tickets” {id. at 825) is barred

in relation to interstate transportation services of

every kind.

To be sure, Section 316(d) speaks only of ‘'any com

mon carrier by motor vehicle,” and not of terminals

or terminal restaurant facilities as such. But 49

U.S.C. 303(a) (19) defines the “services” and “trans

portation” to which Part I I of the Act applies as

including “ all facilities and property operated or con

trolled by any * * * carrier * * * used in the trans

portation of passengers or property in interstate or

foreign commerce or in the performance of any

service in connection therewith” (emphasis added).

unlawful. I t shall be unlawful for any common carrier by

motor vehicle engaged in interstate or foreign commerce to

make, give or cause any undue or unreasonable preference or

advantage to any particular person * * * in any respect what*

soever; or to subject any particular person * * * to any.unjust

discrimination or any undue or unreasonable prejudice or dis

advantage in any respect whatsoever * *

The facilities involved in the present case are so

controlled. The Trail ways Bus Terminal in Richmond,

Virginia, is owned by Trailways Bus Terminal, Inc.

(R. 18). According to an authenticated copy of the

records of the Interstate Commerce Commission, re

printed in the Appendix, pp. 29-31, infra,4 Virginia

Stage Lines, Inc., a “common carrier by motor vehicle,”

owns fifty percent of the stock in Trailways Bus Ter

minal, Inc., and operates the terminal as a joint facility

with the Carolina Coach Company, also a “common car

rier by motor vehicle” (see Williams v. Carolina Coach

Co., I l l P. Supp. 329 (E.D. Va.), affirmed, 207 P. 2d

408 (C.A. 4) ; Keys v. Carolina Coach Co., 64 M.C.C.

769).

The fact that the restaurant in the terminal is leased

by Trailways Bus Terminal, Inc., to Bus Terminal

Restaurant of Richmond, Inc., is thus immaterial

here. Since a carrier is prohibited from enforcing

racial segregation in facilities which it operates or

controls, it may not evade its statutory responsibili

ties in this respect by leasing such facilities to an

other. The paramount federal duty of nondiscrimi

nation is not delegable and cannot be discharged

4 “ [AJnnual or other reports of earners made to the Com

mission * * * shall be preserved as public records * * 49

U.S.C. 16(13). These public records, including “copies of and

extracts from” them, properly certified and sealed, “shall be

received as prima facie evidence of what they purport to be

* * * in all judicial proceedings * * Ibid ./ see 49 U.S.C.

304(d). The extracts from the annual reports of the carrier

which appear in the Appendix, pp. 29-32, infra, have been cer

tified by the Secretary under the Commission’s seal as required.

9

through, lease of facilities.6 I t follows that maiute-

nance of segregation in the Richmond terminal restau

rant, and its enforcement by the state, violate the

Interstate Commerce Act which thus provides a full

defense against the trespass charge on which the judg

ment below was based. Cf. Solomon v. Pennsylvania

R.E., 96 ¥. Supp. 709, 712 (S.D.N.Y.).

I I

Ever since Gibbons v. Ogden, 9 Wheat. 1, “the

states have not been deemed to have ..the authority to

impede substantially the free flow of commerce from

.state to state * * *.” Southern Pacific Co. v. Arizona,

325 U.S. 761, 767. This “ long-recognized distribution

of power between national and state governments”

has been predicated in some cases upon the expressed

or the presumed intention of Congress (id, at 768),

and in others “ upon the implications of the commerce

clause itself” (ibid.). Thus, even in the absence of

congressional action, the Commerce Clause, of its own

force, requires invalidation of unreasonable state-

imposed burdens on interstate commerce. See Morgan

v. Virginia, 328 U.S. 373; Hall v. DeCuir, 95 U.S. 485.

See also Seaboard Air Line By. v. Blackwell, 244 U.S.

6 Moreover, the terms of the lease itself evidence sufficient con

trol by the carrier for purposes of Section 303(a) (19) : the termi

nal restaurants are required to be operated in keeping with the

character of service maintained in an up-to-date, modern bus ter

minal (It. 14); the lessee must obtain the lessor’s permission be

fore selling any commodity not usually sold or installed in a “bus

terminal concession” (R. 11); the lessee must refrain from sell

ing on buses operating in or out of the terminal (R. 16); and,

upon notice from the lessor, the lessee must also refrain from

making sales through the windows of the buses (R. 16).

10

310; South Covington Ry. v. Covington, 235 U.S. 537.

Whether any particular state legislation is invalid

depends upon whether “ it unduly burdens * * * com

merce in matters where uniformity is necessary * *

Morgan v. Virginia, supra, at 377. And whether “ the

statute in question is a burden on commerce” depends

upon the “situation created by the attempted enforce

ment of * * * [the] statute * * *.” Id. at 377-378.

Thus, in Morgan v. Virginia, supra, a Virginia

statute required racial segregation in interstate

buses. Stating that the issue of the statute’s

validity must be decided “as a matter of bal

ance between the exercise of the local police power

and the need for national uniformity in the regulations

for interstate travel,” the Court concluded “ * * *

that seating arrangements for the different races in

interstate motor travel require a single, uniform rule

to promote and protect national travel.” 328 U.S. at

386. See also Henderson v. United States, 339 U.S.

816; Mitchell v. United States, 313 U.S. 80; Chance v.

Lambeth, 186 F. 2d 879 (C.A. 4), certiorari denied,

341 U.S. 941; Whiteside v. Southern Bus Lines, Inc.,

177 F. 2d 949 (C.A. 6).

The application of a state statute is not the only

official act of a state which has been found by the

Court to be invalid as a burden on interstate com

merce. In Morgan v. Virginia, supra, at 379, the

Court also observed that “ * * * a final court order is

invalid which materially affects interstate commerce.”

Accord, Kansas City So. Ry. Co. v. Raw Valley Hist.,

233 U.S. 75. An order of an administrative commis

sion may also constitute a burden on interstate com-

11

merce. Morris v. Duty, 274 U.S. 135; St. Louis-S.F.

Ry. v. Public Service Commission, 261 U.S. 369;

Atlantic Coast Line R. Co. v. North Carolina Corp.

Commission, 206 U.S. 1. Similarly, the federal courts

have ruled that a burden may be created by the state

enforcement of a private regulation. Chance v. Lam

beth, supra; Whiteside v. Southern Bus Lines, Inc.,

supra.

In the present case, petitioner was ejected from the

restaurant and arrested by a state police officer,

prosecuted by the state for violation of a law enacted

by the state legislature, and convicted by a state judge

in a state court. Thus, whether the trespass convic

tion be isolated as an unconstitutional application of

the state trespass law or whether it be regarded as a

combination of state legislative, executive, and judicial

action, it nevertheless is clearly the type of activity

which is embraced within the scope of the Commerce

Clause.6

I t is not material that the present case

involves racial segregation in dining facilities at

bus terminals rather than on the bus itself. The fur

nishing of food to interstate passengers is as much a

part of interstate commerce in the one place as the

other. See Philadelphia, B. & W. R. Co. v. Smith,

250 U.S. 101; Henderson v. United States, 339 U.S.

816. Facilities are, of course, not removed from inter-

6 Some courts have indicated—correctly, we believe—that racial

segregation imposed by a private carrier alone, unsupported by

state authority, would also constitute an unlawful burden on in

terstate commerce. Chance v. Lambeth, supra, at 882-883;

Whiteside v. Southern Bus Lines, Inc., supra,, at 953; cf. In re

Debs, 158 U.S. 564, 581, 582.

561431— 00----3

12

state commerce simply because they are stationary.

See, e.g., Bice v. Santa Fe Elevator Corp., 331 U.S.

218, 229. The Interstate Commerce Commission, by

asserting jurisdiction over terminal facilities such as

red-cap service, Dayton Union By. Co. Tariff for

Bedcap Service, 256 I.C.C. 289, 299, and station wait

ing rooms and rest rooms, N.A.A.C.P. v. St. Louis-

S.F. By. Co., 297 I.C.C. 335, has demonstrated its recog

nition that a facility may be in interstate commerce

although it is located in a terminal rather than on a

moving carrier.7 This Court, in Henderson v. United

States, 339 U.S. 816, 824, characterized regulations of

a railroad carrier which required segregation of the

races in dining cars as “ unreasonable discriminations”

in violation of Section 3(1) of the Interstate Commerce

Act, 49 U.S.C. 3(1).8 Segregation in terminal dining

7 By striking down racial segregation in station waiting rooms

and rest rooms as violative of the Interstate Commerce Act, the

Commission has recognized that segregation within the confines

of a terminal prejudices and disadvantages a Negro traveler as

unreasonably as segregation on the carrier itself. N.A.A.C.P. v.

St. Louis—S.F. Ry. Co., supra.

8 In A .A.A.C.P. v. St. Louis-S.F. Ry. Co., supra, the Interstate

Commerce Commerce Commission refused to assert jurisdiction,

under Section 3(1), over lunchrooms in the Richmond railway

terminal. However, the Commission’s sole basis for declining

to assert jurisdiction over the lunchroom was that there had

been a nineteen-year lapse in its operation, which, according

to the Commission, indicated that this lunchroom had not

constituted an integral part of the terminal’s common-carrier

functions and therefore was not within its jurisdiction. But,

as the record shows in the present case, the restaurants were

built as an integral part of the interstate terminal facility

(R. 9), and there is no indication that they have not been in

continuous operation since then. Access to the restaurant was

intended to, and did, facilitate interstate travel.

13

facilities, no less than segregation on a moving diner,

constitutes, in the words of Henderson, “unreasonable

discrimination,” “unreasonable prejudice,” and “un

reasonable disadvantage” to the passenger denied

equality of treatment.9

Bus passengers are far more dependent upon termi

nal dining facilities than are railroad passengers.

Unlike bus companies, railroads do not schedule regu

lar stops which are long enough to permit their pas

sengers to eat in terminals. Once a journey by rail has

commenced, railroad passengers normally satisfy

their food requirements during the course of the trip

either by buying sandwiches and eating them while

occupying seats in coaches, or by eating regular meals

in the dining car of the train itself. As a practical

matter, interstate bus passengers ordinarily must ob

tain their meals from the facilities offered at the bus

terminal or go hungry. Thus, bus terminal restau

rant facilities are a precise equivalent of dining cars

on railroad trains.

The decision of the court of appeals in Williams v.

Howard Johnson’s Restaurant, 268 F. 2d 845, 848

(C.A. 4), assuming that it was correctly decided, does

not compel an opposite conclusion. In that case the

court decided that a restaurant located on an inter

state highway in the city of Alexandria is not engaged

in interstate commerce “merely because in the course

of its business of furnishing accommodations to the

8 This Court has similarly characterized, and has held repug

nant to the Interstate Commerce Act regulations segregating

Negroes from whites in Pullman cars. Mitchell v. United

States, supra.

14

general public it serves persons who are traveling from

state to state,” and it concluded that the restaurant

was “an instrument of local commerce.” 10 The Trail-

ways bus restaurant in Richmond, on the other hand,

is located in an interstate bus terminal, was con

structed at the same time that the terminal was con

structed (R. 9), and was leased upon conditions re

quiring that the lessee obtain the lessor’s permission

before selling any commodity not usually sold or in

stalled in a “bus terminal concession” (R. 11), and

that the restaurant be operated “ in keeping with the

character of service maintained in an up-to-date, mod

ern bus terminal” (R. 14). There is therefore no

warrant for designating the restaurant in this case as

an instrument of local commerce.” Even though it

may incidentally serve local traffic (R. 23), it clearly

is primarily an instrument of interstate travel, and in

this case it was in fact sought to be used by petitioner

in connection with his interstate journey. Cf. Atchi

son, Topeka & Santa Fe By. Go., 135 I.C.C. 633, 634-

635.

Racial discrimination or segregation interferes with

a “single, uniform rule to promote and protect national

travel” (Morgan v. Virginia, supra, at 386), and

thereby imposes a burden on interstate commerce. In

instances in which rules have varied from state to

state with respect to racial discrimination or non

discrimination in interstate transportation facilities,

the Court has held invalid statutes requiring racial

10 The plaintiff in the Williams case contended that the pri

vate segregation itself constituted a burden on interstate com

merce. Cf. footnote 6, supra.

15

discrimination (see, e.g., Morgan v. Virginia, supra)

because of their tendency to undermine any “ single,

uniform rule to promote and protect national travel.”

See Bob-Lo Excursion Co. v. Michigan, 333 U.S. 28,

40. I f diversity of racial rules from state to state is

to be avoided, and uniformity with respect to inter

state travel achieved, racial discrimination and segre

gation, be it by state statute no matter how enforced,

must be deemed invalid. Interstate commerce would

flow more smoothly if states did not use their criminal

process to support racially discriminatory policies of

the proprietors of such restaurants, and if the latter

were thereby encouraged to serve all interstate passen

gers indiscriminately instead of refusing to serve some

of them on grounds irrelevant to the interstate travel.

Moreover, enforcement of racial discrimination,

such as that involved in the present case, supports

and accentuates an unreasonable disadvantage and

prejudice to a class of interstate travelers. Cf. Hen

derson v. United States, 339 U.S. 816, 824; Mitch

ell v. United States, 313 U.S. 80. Since interstate bus

travel cannot be conducted without regularly sched

uled bus stops, and since dining facilities at such

stops are an integral and essential part of interstate

bus service, the disadvantage and prejudice cannot be

avoided by the interstate Negro bus traveler. In

N.A.A.C.P. v. St. Louis-S.F. By. Co., 297 I.C.C. 335,

347, the Interstate Commerce Commission, in ordering

the end of segregation in interstate rail travel,

declared:

* * * The disadvantage to a traveler who is

assigned accommodations or facilities so desig-

16

nated as to imply his inherent inferiority solely

because of his race must be regarded under

present conditions as unreasonable. Also, he is

entitled to be free of annoyances, some petty

and some substantial, which almost inevitably

accompany segregation even though the rail

carriers, as most of the defendants have done

here, sincerely try to provide both races with

equally convenient and comfortable cars and

waiting rooms.

Racial segregation works a serious and unwar

ranted burden and hardship upon those against whom

it operates, and the prospect of encountering it in

bus terminals surely operates as a deterrent to a

Negro contemplating an interstate bus journey. Na

tional travel is hindered by the enforcement of such

arbitrary discriminations in service. Persons hold

ing the same tickets, whatever their race, color, reli

gion or other irrelevant personal characteristic, are

entitled to the same service and treatment when they

travel in interstate commerce. Under the controlling

provisions of federal law, a Negro passenger is free to

travel the length and breadth of this country without

hindrance or humiliation, and to receive precisely the

same service, no more and no less, as any other

passenger.

I l l

In the Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3, 11, this Court

declared that “ positive rights and privileges are un

doubtedly secured by the Fourteenth Amendment,”

which “nullifies and makes void all State legislation,

and State action of every kind, which impairs the

17

privileges and immunities of citizens of the United

States, or which injures them in life, liberty or prop

erty without due process of law, or which denies to

any of them the equal protection of the laws.” Ibid.

(emphasis added). Racially discriminatory acts of in

dividuals, moreover, are insulated from the proscrip

tion of the Fourteenth Amendment only insofar as

they are “ unsupported by State authority in the shape

of laws, customs, or judicial or executive proceed

ings,” or are “ not sanctioned in some way by the

State.” Id. at 17.

That the discrimination in the present case was of

private origin is irrelevant. The application of a

general, nondiscriminatory, and otherwise valid law

to effectuate a racially discriminatory policy of a pri

vate agency, and the enforcement of such a discrimi

natory policy by state governmental organs, has been

held repeatedly to be a denial by state action of rights

secured by the Fourteenth Amendment. Thus, in

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1, the judicial enforce

ment of private racially restrictive covenants by

injunction was held violative of the Fourteenth

Amendment; similarly, in Barrows v. Jackson, 346

U.S. 249, this Court decided that such covenants

could not be enforced, consistently with the Four

teenth Amendment, by the assessment of damages for

their breach; and in Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U.S. 501,

this Court ruled that the criminal courts could not be

used to convict of trespass persons exercising their

rights of free speech in a privately-owned company

18

town,11 See also Kreshik v. St. Nicholas Cathedral,

363 ILS. 190, 191; N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama, 357 U.S.

449, 463.

If, in Shelley, the action of a state judiciary alone

was in question, in the present case each branch of

state government contributed directly and substan

tially to the support and enforcement of the terminal

restaurant’s discriminatory policy. By the active in

tervention of the executive and judicial branches of

that government, applying a law passed by its legis

lature, “the full panoply of state power” (Shelley

v. Kraemer, supra, at 19) was exerted to deny to

petitioner, on the ground of race or color, the enjoy

ment of the right to equal treatment in the use of

accommodations open to the public generally—here

interstate travel facilities—a right clearly secured by

11 I t is immaterial that the state judicial action which en

forces the denial of rights guaranteed by the Fourteenth

Amendment may be procedurally fair. Such action is consti

tutionally proscribed “even though the judicial proceedings

* * * may have been in complete accord with the most rigor

ous conceptions of procedural due process.” Shelley v. Krae

mer, supra at 17. See also Bridges v. California, 314 U.S. 252;

American Federation of Labor v. Swing, 312 U.S. 321; Cant

well v. Connecticut, 310 U.S. 296. Similarly, it is no answer

to say that the state courts stand ready to convict white per

sons of trespass should they refuse to leave bus terminal res

taurants from which they have been excluded because of race

or color. “The rights created by the first section of the Four

teenth Amendment are, by its terms, guaranteed to the indi

vidual. The rights established are personal rights. * * * Equal

protection of the laws is not achieved through indiscriminate

imposition of inequalities.” Shelley v. Kraemer, swpra at 22.

19

the Fourteenth Amendment. See Mitchell v. United

States, 313 U.S. 80,94.12

The right not to be excluded solely on account of race

from facilities open to the public has been held to ex

tend to such accommodations as public beaches and

bathhouses (Mayor and City Council of Baltimore v.

Dawson, 350 U.S. 877, affirming 220 F. 2d 386 (C.A.

4 ) ),13 golf courses (Holmes v. City of Atlanta, 350 U.S.

879, reversing 223 F. 2d 93 (C.A. 5)),14 park and recre

ational facilities {New Orleans City Park Improve

ment Assoc, v. Detiege, 358 U.S. 54, affirming, 252 F.

2d 122 (C.A. 5)),15 and theatres {Muir v. Louisville

Park Theatrical Ass’n., 347 U.S. 971, reversing 202 F.

2d 275 (C.A. 6), and remanding for consideration in

“ There, the Court stated that “ [t]he denial to appellant of

equality of accommodations because of his race would be an

invasion of a fundamental individual right which is guaranteed

against state action by the Fourteenth Amendment.” See also

McCabe v. Atchison, T. & S.F. Ry., 235 U.S. 151, 160-162.

13 See also City of Petersburg v. Alsup , 238 F. 2d 830 (C.A.

5) , certiorari denied, 353 U.S. 922; Williams v. Kansas City,

Mo., 104 F. Supp. 848 (W.D. Mo.), affirmed, 205 F. 2d 47 (C.A.

8), certiorari denied, 346 U.S. 826; Draper v. City of St. Louis,

92 F. Supp. 546 (E.D. Mo.), appeal dismissed, 186 F. 2d 307

(C.A. 8); Lawrence v. Hancock, 76 F. Supp. 1004 (S.D. W.

Va.).

14 See also Moorhead v. City of Ft. Lauderdale, 152 F. Supp.

131 (S.D. Fla.), affirmed, 248 F. 2d 544 (C.A. 5); Holley v.

City of Portsmouth, 150 F. Supp. 6 (E.D. Y a.); Ward v. City

of Miami, 151 F. Supp. 593 (S.D. Fla.), affirmed, 252 F. 2d 787

(C.A. 5); Hayes v. Crutcher, 137 F. Supp. 853 (M.D. Tenn.);

Augustus v. City of Pensacola, 1 R.R.L.R. 681.

15 See also Lonesome v. Maxwell, 220 F. 2d 386 (C.A. 4);

Augustus v. City of Pensacola, supra; Moorman v. Morqan,

285 S.W. 2d 146 (Ky.).

20

light of Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483,

and “conditions that now prevail” )-16

A restaurant, like a theatre, a common carrier, a

school, a beach, a pool, a park, or a golf course, is a

place of public accommodation. The federal courts

have held, therefore, that rights guaranteed by the

equal protection clause are contravened when a private

lessee of a state-owned restaurant engages in racially

discriminatory practices. Derrington v. Plummer, 240

F. 2d 922 (C.A. 5), certiorari denied, 353 U.S. 924;

Coke v. City of Atlanta (N.D. Ga.).17 These holdings

illustrate, moreover, that where the state enforces or

supports racial discrimination in a place open for the

use of the general public—as, in this case, interstate

transportation facilities—it infringes Fourteenth

Amendment rights notwithstanding the private origin

of the discriminatory conduct.18

Uor is it relevant that the property upon which the

discrimination occurs is privately owned. State laws

which require or permit segregation of the races on

privately owned interstate motor buses are invalid

under the Fourteenth Amendment. Gayle v. Brow-

16 See also Henry v. Greenville Airport Commission (C.A. 4),

decided April 20, 1960 (waiting room in a municipal airport).

17 Cf. Nash v. Air Terminal Services, 85 F. Supp. 545 (E.D.

V a .); Air Terminal Services, Inc. v. Rentzel, 81 F. Supp. 611

(E.D. Va.).

18 Accord, Muir v. Louisville Park Theatrical Ass'n., supra;

City of Greensboro v. Simkins, 246 F. 2d 425 (C.A. 4); Der

rington v. Plummer, supra; Tate v. Department of Conserva

tion, 133 F. Supp. 53 (E.D. Va.), affirmed, 231 F. 2d 615

(C.A. 4), certiorari denied, 352 U.S. 838; Nash v. Air Terminal

Services, supra; Lawrence v. Hancock, 76 F. Supp. 1004 (S.D.

W. Va.).

der, 352 U.S. 903; Flemming v. South Caroli?ia Elec

tric & Gas Co., 224 F. 2d 752, appeal dismissed, 351

U.S. 901; see Mitchell v. United States, 313 U.S. 80,

94. Racial discrimination by a privately-owned place

of public accommodation may also violate Fourteenth

Amendment rights if such place is financially sup

ported or regulated by the state. Kerr v. Enoch

Pratt Free Library, 149 F. 2d 212 (C.A. 4), cer

tiorari denied, 326 U.S. 721. That the right to

equal treatment in places of public accommodation

is protected by the Fourteenth Amendment against

deprivation by state action is not impaired by the

decision in the Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3, for

there the Court carefully reserved the question

whether the Amendment secured the right to be free

from state-sanctioned discrimination in places of pub

lic accommodations.19

19 The Court emphasized that it was reserving this question

(109 U.S. at 19, 21, 24):

We have discussed the question presented by the law on

the assumption that a right to enjoy equal accommodation

and privileges in all inns, public conveyances, and places

of public amusement, is one of the essential rights of the

citizen which no State can abridge or interfere with.

r Whether it is such a right, or not, is a different question

which, in the view we have taken of the validity of the

law on the ground already stated, it is not necessary to

examine.

jJ; * * * *

But is there any similarity between such servitudes [the

: ’ burdens and disabilities incident to feudal vassalage] and

a ; denial by the owner of an inn, a public conveyance, or a

theatre, of its accommodations and privileges to an in-

22

Because an asserted justification for invasion of the

right to be free from state enforcement of racially

discriminatory practices warrants the most searching

judicial scrutiny, such enforcement can withstand

attack, if at all, only where the constitutional right is

subordinated to a countervailing right or interest so

weighty as to occupy a preferred constitutional status.

Gf. Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214, 216.

The narrow issue in the present case is not whether

the right, for example, of a homeowner to choose his

guests should prevail over petitioner’s constitutional

right to be free from the state enforcement of a

policy of racial discrimination, but rather whether

the interest of a proprietor who has opened up his

business property for use by the general public—in

particular, by passengers travelling in interstate com-

dividual, even though the denial be founded on the race or

color of that individual? Where does any slavery or ser

vitude, or badge of either, arise from such an act of de

nial? Whether it might not he a denial o f a right which,

i f sanctioned by state law, would he obnoxious to the pro

hibitions of the Fourteenth Amendment, is another ques

tion.

* * * * *

Now, conceding, for the sake of the argument, that the

admission to an inn, a public conveyance, or a place of

public amusement, on equal terms with all other citizens,

is the right of every man and all classes of men, is it any

more than one of those rights which the states by the

Fourteenth Amendment are forbidden to deny to any per

son? And is the Constitution violated until the denial

of the right has some State sanction or authoiity? [Em

phasis added.]

23

meree on a federally-regulated carrier—should so pre

vail.20

20 During the debate on the bill introduced in the Senate by

Charles Sumner of Massachusetts on December 20, 1871, to

amend the Civil Eights Act of 1866, 14 Stat. 27, which served

as the precursor to the Civil Eights Act of 1875, 18 Stat. 336,

Senator Sumner distinguished between a man’s home and places

and facilities of public accommodation licensed by law: “Each

person, whether Senator or citizen, is always free to choose who

shall be his friend, his associate, his guest. And does not the

ancient proverb declare that a man is known by the company he

keeps? But this assumes that he may choose for himself.

His house is his ‘castle’; and this very designation, bor

rowed from the common law, shows his absolute independence

within its walls; * * * but when he leaves his ‘castle’ and goes

abroad, this independence is at an end. He walks the streets;

but he is subject to the prevailing law of Equality; nor can he

appropriate the sidewalk to his own exclusive use, driving into

the gutter all whose skin is less white than his own. But no

body pretends that Equality on the highway, whether on pave

ment or sidewalk, is a question of society. And, permit me to

say,, that Equality in all institutions created or regulated by

law is as little a question of society” (emphasis added). After

quoting Holingshead, Story, Kent and Parsons on the common

law duties of innkeepers and common carriers to treat all alike,

Sumner then said: “As the inn cannot close its doors, or the

public conveyance refuse a seat to any paying traveler, decent

in condition, so it must be with the theater and other places

of public amusement. Here are institutions whose peculiar

object is the ‘pursuit of happiness,’ which has been placed

among the equal rights of all.” Cong. Globe, 42d Cong., 2d

Sess., 382-383. See also Cong. Eec., 43d Cong., 1st Sess., 11:

“Our colored fellow-citizens must be admitted to complete

equality before the law. In other words, everywhere in every

thing regulated by law, they must be equal with all their fellow

citizens. There is the simple principle on which this bill

stands” (emphasis added); Cong. Globe, 42d Cong., 2d Sess.,

381: “The precise rule is Equality before the Law; * * *

that is, that condition before the Law in which all are alike—

being entitled, without any discrimination to the equal enjoy

ment of all institutions, privileges, advantages and conveniences

created or regulated by law * * *” (emphasis added).

24

Courts have long placed restrictions upon pro

prietors whose operations are of a public nature, af

fecting the community at large. As early as Munn v.

Illinois, 94 U.S. 113,126, this Court said:

Property does become clothed with a public

interest when used in a manner to make it of

public consequence, and affect the community

at large. When, therefore, one devotes his

property to a use in which the public has an in

terest, he, in effect, grants to the public an

interest in that use, and must submit to be

controlled by the public for the common good,

to the extent of the interest he has thus

created. * * *

This Court in Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U.S. 501, 506,

similarly rejected the contention that the rights of a

proprietor of property open to the public were coex

tensive with those of a homeowner:

Ownership does not always mean absolute do

minion. The more an owner, for his advan

tage, opens up his property for use by the

public in general, the more do his rights be

come circumscribed by the statutory and con

stitutional rights of those who use it * * *.21

21 Of. Republic Aviation Gorp. v. National Labor Relations

Board, 324 U.S. 793, 798, 802, n. 8; National Labor Relations

Board v. Babcock da Wilcox Go., 351 U.S. 105, 112. Although

Marsh v. Alabama involved the rights of free speech and

religion, its principle is equally applicable to other Fourteenth

Amendment rights, and this Court, in Shelley v. Kraemer,

supra, at 22, has specifically applied it to the right to equal

protection of the laws, stating that “the power of the State

to create and enforce property interests must be exercised

within the boundaries defined by the Fourteenth Amendment.

Of. Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U.S. 501 (1946).”

25

Only recently, a Washington court applied the

Marsh principle in rejecting the right of an owner

of a shopping center to obtain an injunction from a

state court restraining peaceful picketing on the pri

vately-owned sidewalks of the shopping center. Free

man v. Retail Clerks Local 1207 (Kings County

Super. Ct., Washington), decided December 9, 1959

(28 U.S. Law Week 2311). The court noted that the

owner had contracted away his right to private and

personal use and occupancy, and emphasized that in

terference with the owner’s fundamental right of pri

vacy was not involved because he had devoted his

property for use by the general public. In April of

this year, the Superior Court of Raleigh, North Caro

lina, relying on the Marsh decision, dismissed trespass

charges against forty-three Negroes who had been ar

rested for demonstrating on the privately-owned side

walks of a shopping center against segregated lunch

counters in the stores of the shopping center. See

New York Times, April 23, 1960, p. 21, col. 1.

The concepts of “private property” and “state

action,” as Marsh illustrates, do not fall into neat,

precise categories. In the last analysis, the determi

nation whether private conduct has been so “ pano

plied” by governmental action, power, or support

that it may fairly be judged by the standards of the

Fourteenth Amendment is, like so many questions of

constitutional law, one of proximity and degree. As

already noted, this case concerns, not an individual

home owner, but an essential public transportation

facility in the direct stream of interstate commerce

26

and subject to effective federal regulation under the

Interstate Commerce Act. While the facility here

may be distinguished from a company town, such as

was involved in Marsh v. 'Alabama, or from the pri

mary voting machinery involved in Terry v. Adams,

345 U.S. 461, 473, and Smith v. Allwright, 321 U.S.

649, we think the underlying rationale of those cases

is equally applicable here. The Trailways Bus Ter

minal in Richmond, Virginia, is not comparable to

a home or even to a corner grocery store. Though

privately owned, it is an interstate facility operated

for the benefit of the general public, in relation to

which the broad constitutional principle of Marsh v.

Alabama may properly be applied. Cf. Boman v.

Birmingham Transit Co., decided July .12, 1960, in

which the Fifth Circuit held that because of “the

peculiar function” performed by a bus transit com

pany as a public utility “ and its relation to the City

and State of Alabama through its holding of a special

franchise to operate on the public streets of Birming

ham,” the acts of the bus company in requiring

racially segregated seating were “state acts,” and

thus violated the constitutional rights of Regro

passengers.

To be sure, local trespass laws are directed towards

the avoidance of breaches of the peace. But petition

er’s conduct was peaceable and orderly; if any threat to

the peace was involved, it arose solely from the racial

discrimination against him. Accordingly, if the state’s

legitimate interest in preventing breaches of the peace

is made the basis of governmental intervention in such

a situation, its intervention could be constitutionally

27

justified only if directed at the source of the threat to

the peace, rather than at the person who is being dis

criminated against.

The federal statutory and constitutional rights here

invoked are derived from not only the Interstate

Commerce Act and the Fourteenth Amendment, but

the Civil Rights Acts as well. 42 U.S.C. 1981 pro

vides: “All persons within the jurisdiction of the

United States shall have the same right in every

State and Territory to make and enforce contracts,

* * * and to full 'and equal benefit of all laws and

proceedings for the security of persons and property

as is enjoyed by white citizens * * 42 U.S.C.

1982 provides: “ All citizens of the United States

shall have the same right, in every State and Terri

tory, as is enjoyed by white citizens thereof to * * *

purchase * * * real and personal property.” Refer

ring to similar statutory provisions involving jury

service, this Court has declared: “For us the majestic

generalities of the Fourteenth Amendment are thus

reduced to a concrete statutory command when cases

involve race or color which is wanting in every other

case of alleged discrimination.” Fay v. New York,

332 U.S. 261, 282-283. See also Shelley v. Kraemer,

334 U.S. 1, 10-12; Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U.S. 24, 30-34.

In Virginia v. Rives, 100 U.S. 313, 318, the Court,

speaking of these statutes, said:

The plain object of these statutes, as of the

Constitution which authorized them, was to

place the colored race, in respect of civil

rights, upon a level with whites. They made

the rights and responsibilities, civil and crimi

nal, of the two races exactly the same.

28

When a state abets or sanctions discrimination

against a colored citizen who seeks to patronize a

business establishment open to the general public,

the colored citizen is thereby denied the right “ to

make and enforce contracts” and “ to purchase per

sonal property” guaranteed by 42 U.S.C. 1981 and

1982 against deprivation on racial grounds.

CONCLUSION

I t is respectfully submitted that the judgment

below should be reversed with directions to vacate the

conviction and dismiss the criminal proceedings

brought against petitioner.

J . L e e R a n k i n ,

Solicitor General.

H a r o l d R . T y l e r , J r .,

Assistant Attorney General.

P h i l i p E l m a n ,

Assistant to the Solicitor General.

H a r o l d H . G r e e n e ,

R i c h a r d J . M e d a l ie ,

D a v id R u b i n ,

G e r a l d P. C h o p p i n ,

Attorneys.

S e p t e m b e r 1960.

1T.S. 80VERIIKEHT PBJNT1N8 O FPIC Ii lff«0

A P P E N D I X

ANNUAL REPORT

I. C. (3: D oc**t No. ,

ORGANIZATION AND CONTROL

1. S ta te full and exact nam e of respondent m aking th is report:

V i r g i n i a S ta g e L in e s * I n c .

doing batiiM M a a . - Y . i r £ L n ia _ . T r a i . ( w a y s — ....................................... ........... .................................................... —..........................--— ......... *

2, H*k»% title ,j*nd address of officer, owner or partner to whom correspondence concerning th is repo rt should be addressed.

___ ______ D ,_ S . M a rsh a llw ________ O f f i c e Manag e r ____ ._____ l._ ,...........

' f r *5 C h a r l o t t e s v i l l e ^ V i r g i n i a

................................................ (city)...... .... &**•)

1 1 4 - 4 t h S t , ,

(N um im ) (Street)

3. Address of dffiee where accounting records are m aintained:

. . . 1 1 4 - 4 t h „ S t .Jl. .S [.„ E . ’ V ir g in ia

T ~ ! ..........(State''

C h a r l o t t e s v i l l e ..................

(Number) (S tm t) ............ ......... ... .................... <City> - ••» '■

4. Carrier is ........Corporation ______*..................... ........... .......................... ................................ ..... ...................

(XadWidufti, partTOrsbip, corporation, etf.) .

&. It a partnersh ip , s ta te th e nam es and addresses of each p a rtn e r , including silen t or lim ited , a n j th e ir in terests; ,

' ■ Name AddrtM ■ ; 1 Pn>foH

' i.

o n ____19.??.

6. If a sorporation, association,, or o th er sim ilar form of enterprise:

A. Incorporation or organisation was—

In the S ta te o f ____ V ir g in ia ------ ------------ -----------------------...-------

B. T he directors’ nam es, addresses, and te n sa of office are:

S, a , Jessup*1** Chario11 e s v ^ a . __Qoe y ea r or u n t i l

....... p„ SA J e s s u p ___ _________ _________.Wa,sklri&tan#..-EA..C*.------------ —.— q t a j x S-.

__ .J e s su p ................................. ........................JCharJLfl.tt&sxijLle>-Aaw._i—i--------- ifaily. ..sJkc£.tted.*—

___ l«.JL ,..lessujA __________________ „..CixaiilQtte.sxillfi*-Aaw...,.-.i-..... -----

Jks G. Muncy _ C h a r lo t t e s v i l l e , Va.__________ _ ___............ -............. _

~F~

——— r-— rr.*?‘ *r~*rm-,~-7-T-rr • T~."r ~tvTr’—"ttt-

C. The namea and titlea rtf principal general officers are: ...............< .... .. .....

N a m t Title

S, A, Jessu p Chairman o f Board

......................... c :* X “ je s su E ......................................... " g r is a g n t " ^ G en'eral'l^ n g e f ' ......

.................... -Je.ES.up.........................................................yiCfi..jP.re.5Me.«.t........................................ .

....... ..................v r,_ M?»we.y................................................ Sft£X<:XazJ..b.. As a i s la n t.. Ti^.a sure r _

....... ............ ..................................................... .JrfiaAWsr-,....

.......................... Rennalda........................................ -..............A s.5 l§ .tM t...|e cre t^ y _ _ ..------- ...

R, .A;. T r ic e ............................. ..................A s s is ta n t S c c r e t t g i ; . : ; ^ , ,^ ____....

C raft V ice -P resident ! ........

...............................................- ........................- ................................. - ......................................................—

........................ ..............................------------------rrrrrrrrr"-rxr-:rr-

. . . . . . . ----

. . . . --- W;--------»—

29

56

14

31

0

-

6

0

{F

ac

e

p.

28

)

N

o,

IS. List of companies under common oootroi with resjKxi'Vrtt

Lis*

So.

. C h a r l o t t e s y i l i e A i b e m a r ;. CU

.T r a i iw a ir s . S e r . Y . i .„...............................

S a f e w a y . I r a n s i . t - .C .c 4....................... ..... .............

.Lyncljj3«rig..TxAXi!a.t..C:v'...................... . . ..

. S a f e t y . . M o.t© x.. 1 c j m &jlL. .CJ«...........................

- S a f e w a y - lx a x I .S L ,- . J x t '. . . . ..................... ........... .

.All£nt^HTi.k.fieajiliX!iz..-lxaLaaxi- G. ̂ ...

.IraiiWay.5..Biju3—Tft.rjiuxja.1 . .la;... .. .. ...

V aA..J?e P S i . . C o. i a . . B e 1 1 1 i n j . . C>,,. I t . - .,

- l £ a i l w ra y x . . j£ X .m .r ta i . . .a K . .W a i ih ^ n g t? .n ...

- I i a i j j» 'a y 5 . . .o i . . f i e .w . . - £ c a t x a t t d ._____ ______

In.,

i ‘Wa» - o t t e ?! i - I le Va_.

Wa t.nfil.on Do Co

w imx.ngj.tm.,.. N» .Co__

ly;nr.hibur.,;.. . V.a»

H.<xC.,'.Ke.. v i . ..... .

k ia n s t : : ! 1 ..Do C«

...

guiunoxta. . Va* ..

Char i i . e V a»

Wa. ?.b xngt on D». C.....

toasL-.iigton D._ Co

J o i n t .

. JoyntL

. j.Qtn.t.

Jsjxn.t-

. Jo in t,

jo in t

J o in t .

M anagem ent...

M a n a g em en t..

i jn a g e m e n .t .

^ a g e r o e n t . . .

Management...

M anagemnt...

.ManagstK.ng...

F a c i l i t y .___

M a n a H e m e .n t ..

F a c i l i t y . ____

. Management

14. Furnish complete list showing ail companies controlled by respondent, either directly or indirectly. List under each directly con

trolled company the companies controlled by it and under each such company any others of more rem ote control. Each step of control

should be appropriately indented from the left margin. After each company sta te the percentage, if any, of the voting power represented

by securities owned by the im mediately controlling company.

LineNo,

21

22

»

24

25

»

27

28

29

S©

81

32

33

34

3h

Allentown h Reading Tra n s i t A:, entown Pa.,...... IJOjC Stc;.k Owner.ship

lif t A .1 W ays.. Se ry-it e Wa.\h.,.ngt y*n. . .P y..Co..... ................. 50% Stock Owner s h ip

jo in t Ga r a g e F a c i l i t y -R e s p o n d e n t b .S afew ay ...T ra i i s.i...Inp.;..... W ashington^.._D, . Co

..T railw ay.§...P .u5...Tgm iaft,l.-,..Ini:r.A ..R ichm ond.,..V a5......... .........................................50% S to ck Ownership

. .J i3in.t...TfirJM .na.l..igvgiLtJ.::Re.aE2adent..& C a r o l in a . C g f t . J r . C ^ ..............................

.S a ff iw a y -J r g U -s .,-Ia u 0.i...W auaingtun,,..DA..QA....... ............. ....... .Omer&kip__pf 355 .sh a re s o f t o t a l o f

...................................................... ................................. ............. .................. .i.5.0.0..-9.hft.r;es..out9tgnd.ing..............................

.I ta jJ y a y A .J itrm ijo a l..a £ J fo & h i.n g ta n ....lL .,u ................. ....... .......................... .......5.PJ. Slock..Ow n ersh ip ............

Jflii3X..JjiXjrjLaag.JxLi-LliLy..Reipcnden.t.-&..5ftffiWiis...Trgkii; .-tox-s.*...Waih.ing.t;onJ1...J3A..CA............ ....... .

...Safew ay-Jrajasi.t..£a>v..tfxiiaingtap^..Wa..Ca............... . -.................................15P%J5iQ£L.0!fl2S.C&h.AP-.

Traxlway..s. a t .g e w .E n g la n d ................... ............. ............... ............. .......................... 52%.J.fQfck..QWB£X.3h.ip..

» j...Safe-ty..Mator...Xransi.t..Co^y.Ik,anoKe_..i’a . .................... ...... ............ lQQ2„StQfck..QwnfiXJ5lup..

37

38

30

40

yallgy...Traglway&i. .I n c M.................... . ................ ........................................... 50% Stock Ownership.............

.L ynghbutg .T ransit. Co.c ..Lynchbui g V j. ....... ...... ......... ........ ....... 100% Stock Owner$h i p ............

3 ^ 0 x e e . C o a c h . L i n e I n .:, . T am pa, K c . r . d a ■ ICC D o c k e t M MCF b - tb - J >3 1 , 3 % S t o c k Own e r s h i p

.JUms...R.ibbv>.n. k i n e s . w r.p ».» A.Juand*. K ftn ipx ky ....... ...................... 100% Stock O w n e rs h i p .............

15. Furnish complete list showing companies controlling the respondent. Commence w ith the company which is m ost rem ote and

list under each such company the company im m ediately controlled by it. Each step of control should be appropriately indented from the

left margin. After each company sta te the percentage, if any, of the voting power represented by securities owned by the immediately con

trolling company. Where any company listed is im mediately controlled by or through two or more companies jointly, list all such companies

and list the controlled company under each of them , indicating its sta tus by appropriate cross references.

Line

No.

61

62

63

64

56

88

57

88

89

00

None

30

(M

56

14

31

0

-

6

0

( F

ac

e

p.

28

)

N

o.

-

Schedule *>#».~€O N T SA C T S AND AGRKEMKNTS— ASSOCIATED COM PANIES

1. Furnish th e inform ation called for In item 9 concerning each contract agreement or arrangem ent (w ritten or unw ritten) in effect a t

any tim e during the year betw een the respondent and companies or person* associated w ith the respondent, including ofBeera, directors, stock

holders, owners, partners o r the ir w ires and o ther oloee relatives, or the ir agents, whereby the respondent reoaired m anagem ent, oonatruettoo,

engineering, financial, legal, accounting, purchasing or o ther type of service including th e furnishing erf m aterials and supplies, purchase at

equipm ent and th e leasing of structures, land, and vehicles.

2. T he basis for com puting paym ents such as rental charges, commissions, taxes, m aintenance eoeta. charges for im provem ents, ate.,

should be fully sta ted in th e case of each such contract, agreem ent or arrangem ent.

8. T he to ta l am ount paid by th e respondent during th e year under the term s of each contract, agreem ent, etc., should be sta ted .

4. I f m otor fuel is furnished th e respondent, th e price per gallon should be shown.

8. In connection w ith th e repairing and servicing of the respondent's equipm ent, and the furnishing at o ther m aterials and supplies, the

m ark-up at labor mud m aterials should be stated.

6. Inform ation to be reported in th is schedule shall be furnished for each company or individual to whom th e respondent paid $3,800 or

more during th e year covered by th e report.

7. Do no t include inform ation shown in schedule 9003-A,

$. If th e respondent did no t partic ipate in any such contract or arrangem ent, th a t fac t should be stated.

9. (a) Nam e of oompemy or person rendering service.

(ib) If associate is o ther th a n a principally-owned subsidiary of respondent such as a com pany controlled by persona associated w ith

respondent, furnish names of partners, owners, or stockholders of associate and their proportionate in terest in associate.

(<) C haracter of service.

<«f> B is k of charges,

(«) D ate and term of eon trac t. j ,

( / ) D ate of Commkwkm authorisation , if con tract has received Commission approval.

(g) T o tal charges for year, classified as to purchases, com pensation for service, and reim bursem ent fa r expenses.

Lint

N».

( a i T r a i l w a y s S e r v i c e I n - , „ W a s h i n g t o n , B . C .

( c ) M a i n t e n a n c e & S e r v i c e t o R e v e n u e E q u i p m e n t

( d l C o s t o f a c t u a l w o r k d o n e p l u s f i x e d p e r c e n t a g e o v e r r i d e o n l a b o r , m a t e r i a l s a n d

s u p p l i e s f u r n i s h e d t o c o v e r o v e r h e a d .

( e ) S e p t e m b e r 1 9 4 7 w i t h c a n c e l l a t i o n by e i t h e r p a r t y ____________ ______ _____________________________

( f i N o n e .................. ........................................ ............................................................................................................. ........... .............. J

( g ) N o t a v a i l a b l e ....................................... ........ __ __________ _________ ___ ________ ________

» ....................J i . f f i . v a y . . .T i a l l a ^ . . I a f f - i L . . h a h . . i f i a ^ £ d . . i fp A v £ . . iD .^ e .v t . . I f t r .K . .E c r t . . i 3 X . .A u ib D r i tX - iu a . i c L D a i a A l --------

» ...... ............. —

II .....................X .o r „ .c .O D 4 p e x A tx m ^ y - f t c t i& A n £ . .a » d . .5 a i £ ^ .P x .o in o . t l . a j a . J j i . . t h e . J i£ N . .X p x k .A r e A . . ......................................... .

] |

U _______ , . . .R £ 3 p c M e r i t . . j o j m h . - . i Q i . .S t a u k . .Q l . . l x a i i w a A i i . J 3 j u x . l e i i h m a i , . . . I n c * . . « i u x .h . .A ^ . j o f ! f t r j i L e d . j i i a . j i — ...

m ..................... J f i i i2t..l£xm inaJ..la.cjJLi£y...JUi..RAwj3iacnd^...Y A i^m ia..-iiL iLh..C araiJuia..£ca£k.£ojnpany.^ ---------------- . . . .

IS

gg

m Respondent owns 50% of Stock of T r a i lw ays Terminal o f W a sh in g to n , I n c .

m

m

W ashington, D„ C. which is operated as a jo in t f a c i l i t y w ith S a few a y T r a i l s , I n c .

M

R e sp o n d e n t a l s o h a s working a rra n g em en t .3 w ith v a r io u s o t h e r c a r r i e r s f o r

^ P o o led E q u ip m en t’1 b e tw e e n v a r io u s p o i n t s on an ex c h a n g e eq u ip m en t b a s i s , lihe

c o n t r a c t c o n t e m p la t e s b a la n c in g o u t m ile a g e by e v e n m ile a g e on e x c h a n g e o f

e O P A P m e P t* . . ..................... ............................................................. ..............................................

3£

n

M

M

M

91

99

m

m

m

41

«

31

Moral Ci -rtmx d

CO

56

14

31

0

-

6

0

( F

ac

e

p.

28

)

N

o.

interstate Commerce Commission

BHa^tngton 2 5 ,3B. C.

SEC

COMMERCE COMMISSION

HAROLD D. McCOY, Secretary of the INTERSTATE COMMERCE

COMMISSION, do hereby certify that the attached is a

rue copy of the Title page and pages 3 and 50 taken from

annual report of Virginia Stage Lines, Inc., for

year ended December 31» 1959} "the original of which

on file in this Commission, in my custody as

of said Commission.

IN WITNESS WHEREOF, I have

hereunto set my hand and

affixed the Seal of said

Commission this 8th day

of August, A. D. I960.

32

56

14

31

0

-

6

0

{F

ac

e

p.

Z8

)

N

o.