Lancaster v. Hammond Opinion

Public Court Documents

August 15, 1949

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Lancaster v. Hammond Opinion, 1949. d8297348-ba9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d1c25a81-a7b2-4de5-a2c2-3ec7b19fd49b/lancaster-v-hammond-opinion. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

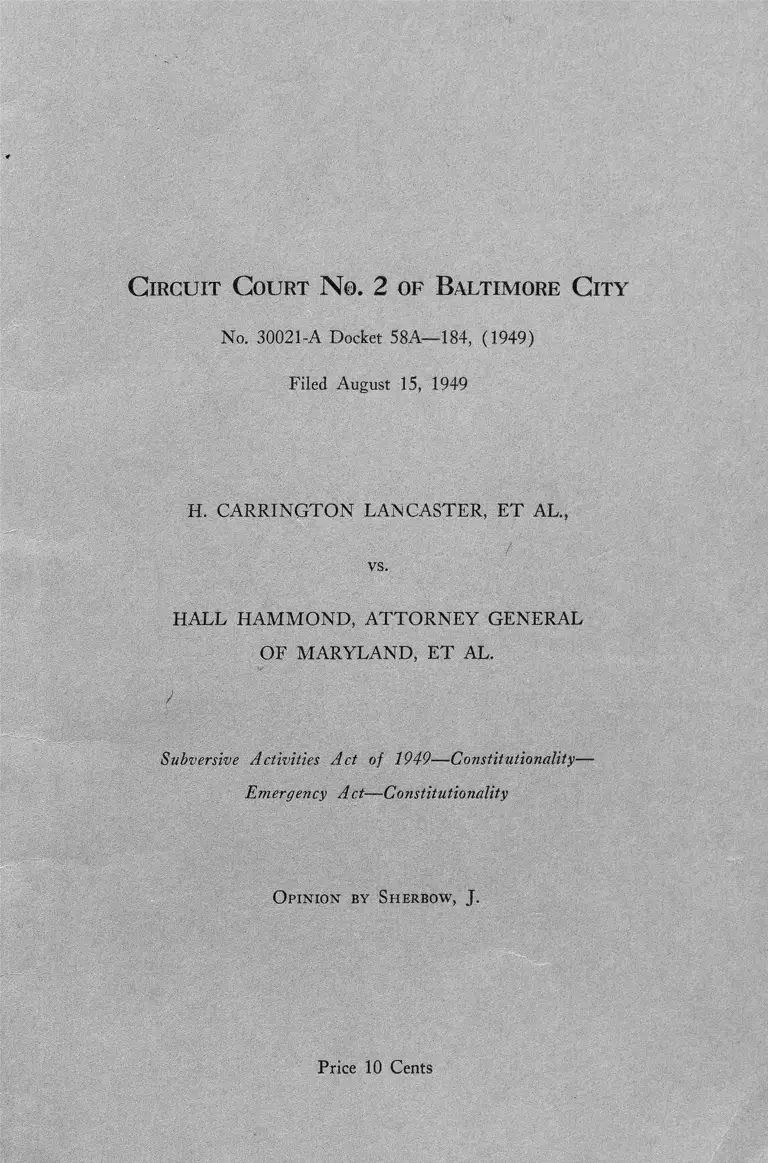

C ircuit C ourt N o. 2 of Baltimore C ity

No. 30021-A Docket 58A— 184, (1949)

Filed August 15, 1949

H . C A R R IN G T O N L A N C A S T E R , E T A L .,

vs.

H A L L H A M M O N D , A T T O R N E Y G E N E R A L

O F M A R Y L A N D , E T A L .

Subversive Activities Act of 1949— Constitutionality—

Emergency Act— Constitutionality

Opinion by Sherbow, J.

Price 10 Cents

Circuit Court No. 2 of Baltimore City

No. 30021-A Docket 58A—184, (1949)

Filed August 15, 1949.

H. CARRINGTON LANCASTER, ET AL„

VS.

HALL HAMMOND, ATTORNEY-GENERAL OF MARYLAND, ET AL.

I. Duke Avnet, Mitchell A. Dubow, Linwood G. Roger, Donald, G. Mur

ray, Robert P. McG-uinn, and Bernard Rosen for the complainants.

Hall Hammond, Attorney-General; J. Edgar Harvey, Deputy Attorney-

General ; Thomas N. Biddison, City Solicitor of Baltimore; Leroy W.

Preston and Hugo A. Ricduti, Assistant City Solicitors, for the defen

dants. __________________

A m ici Curiae

Harold Buchman for National Union of Marine Cooks and Stewards.

Benjamin L. Wolfson and Kenneth R. Hammer, for American Legion,

Department of Maryland.

Dallas F. Nicholas and David Rein, for National Lawyers Guild.

David Scribner for United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of

America.

Subversive Activities Act Of 1919—Constitutionality—Emergency Act—Consti

tutionality.

SHERBOW, J —

The complainants assert that the

“ Subversives Act of 1949,” also known

as the “Ober Bill,” Chapter 86 of the

Acts of the General Assembly of 1949,

is unconstitutional and void. They also

seek to have Chapter 310 of the Acts

of 1949, declaring the “ Subversives Act

of 1949” an emergency measure, like

wise declared unconstitutional and

void.

Parties; History Of The Statutes.

The complainants are four professors

of Johns Hopkins University, a pro

fessor of Morgan State College, a doc

tor of medicine specializing in psychia

try, a professor of George Washington

University, a salesman, a general med

ical doctor, and a sculptor.

Other interested parties received per

mission from the Court to file briefs

as amici curiae. The Attorney-Gen

eral of Maryland and the City Solicitor

of Baltimore have filed demurrers,

asserting both acts are valid and con

stitutional.

As a great number of contentions

have been made, they will be treated

separately under appropriate headings.

By Chapter 721 of the Acts of 1947

a constitutional amendment was pro

posed, and this was approved by the

voters in November, 1948. It is now

Section 11 of Article 15 of the Con

stitution, and is as follows:

“Sec. 11. No person who is a mem

ber of an organization that advocates

the overthrow of the Government of

the United States or of the State of

Maryland through force or violence

shall be eligible to hold any office,

be it elective or appointive, or any

other position of profit or trust in

the Government of or in the admin

istration of the business of this

State or of any county, municipality

or other political subdivision of this

State.”

At the Special Session of the Gen

eral Assembly of 1948, a Resolution

was passed by the Senate (Senate

Joint Resolution No. 2) creating a

Committee on Subversive Activities.

The Committee was directed to make

a study of the laws of this country

and formulate and prepare a legisla

tive program to protect the democratic

principles and ideas of this State from

those seeking to destroy our freedom

and institutions, and to expose and

expurgate subversive and other illegal

activities.

On June 26, 1948, at the annual meet

ing of the Maryland State Bar Asso

ciation, Mr. Frank B. Ober delivered

an address on the subject “ Sedition

versus the Constitution.” (53 Md. Bar

Assn. Transactions, 255.) In the Aug

ust 1948 issue of the American Bar

Association Journal, Mr. Ober also

wrote and published an article entitled

“ Communism versus the Constitution:

The Power to Protect our Free Institu

tions.”

Pursuant to the Senate Joint Reso

lution, the Governor appointed a Com

mittee of eleven citizens, called the

“Commission on Subversive Activities,”

with Mr. Ober as Chairman. The re

port of the Commission was submitted

to the Governor on December 30, 1948,

with an attached draft of a proposed

bill to be entitled “Sedition and Sub

versive Activities.”

The bill was passed, with few amend

ments, on March 31, 1949, to become

effective in the usual manner on June

1, 1949, and became Chapter 86 of the

Acts of 1949. Almost immediately

thereafter it became publicly known

that a group of citizens proposed to

secure sufficient signatures to a peti

tion for a referendum on this bill in

accordance with the provisions of

Article 16 of the Constitution of Mary

land. If the requisite number of sig

natures was obtained the Act would

not go into effect on June 1, 1949, and

could not become effective unless ap

proved by the voters at the General

Election to be held in November, 1950.

On April 1, 1949, Senate Bill No.

528 was introduced to make the earlier

bill an emergency measure, effective at

once. The rules of the Senate were

suspended, the bill placed on second

reading and ordered printed for third

reading. It was passed by the Gen

eral Assembly, and on April 22, 1949,

was signed by the Governor and became

Chapter 310 of the Acts of 1949. The

original bill will be generally referred

to in this opinion as the “ Subversive

Activities Act of 1949” or the “Ober

Bill,” and the second statute will be

referred to as the “Emergency Act.”

The Subversive Activities Act con

tains a number of recitals referring

to the world communist movement, its

objectives and methods, and to other

subversive groups with similar objec

tives, and recites that “the communist

movement plainly presents a clear and

present danger to the United States

Government and to the State of Mary

land.”

Section 1 defines subversive organ

izations, foreign subversive organiza

tions, subversive persons, and others.

It makes a felony certain acts under

the subsection entitled “ Sedition.”

After June 1, 1949, any person who

becomes or who after September 1,

1949, remains a member of a subver

sive organization or a foreign subver

sive organization and is convicted by

a court of competent jurisdiction may

be imprisoned up to five years and

fined not more than $5,000 or both in

the discretion of the Court. Those

convicted under the Act are barred

from holding any office or employment

of the State of Maryland or any poli

tical subdivision, or standing for elec

tion for any public office, or voting in

any general election. The statute pro

vides that such organizations may be

declared subversive by a finding of a

court of competent jurisdiction, the

charter shall be forfeited and all funds

and records and property shall be

seized by the State of Maryland. The

Attorney-General is authorized and

directed to appoint an additional

Assistant to perform the duties of Spe

cial Assistant Attorney-General in

charge of Subversive Activities.

Judges of the Criminal Courts of the

State are directed under certain con

ditions to instruct grand juries to in

quire into violations of this law.

Then follows a group of sections

under the sub-title “Loyalty.” Every

employing group of the State of Mary

land and its political subdivisions is

required to ascertain that all such em

ployees, including teachers, are not

subversive persons, “and that there

are no reasonable grounds to believe

such persons are subversive persons.

In the event such reasonable grounds

exist, he or she as the case may be

shall not be appointed or employed.”

Laborers are excluded. All those em

ployed by the State of Maryland or

its political subdivisions from the first

of June, 1949, shall make a written’

statement, subject to the penalties of

perjury, that he or she is not a sub

versive person as defined by this law.

Reasonable grounds shall be cause for

discharge subject to the right to a

hearing under the provisions of the

Act, with the right of appeal to the

2

courts, and a jury trial, if elected, with

a further appeal to the Court of Ap

peals of Maryland.

Section 15 provides that no person

shall become a candidate for election

for any public office in this state un

less he files with his certificate of

nomination an affidavit that he is not

a subversive person. The certificate

shall not be received for filing by any

election officials, nor placed upon the

ballot or voting machine, if the affi

davit has not been made.

No appropriation of funds of any

character shall be made by the State

to any private institution of learning

until there is filed with the Governor,

the President of the Senate, and the

Speaker of the House of Delegates, on

behalf of the institution, a written

report setting forth procedures it has

adopted to determine whether it has

reasonable grounds to believe that any

subversive persons are in its employ

and the steps taken to terminate em

ployment of such persons. All written

applications for employment shall be

under the penalties of perjury.

The Emergency Act

The complainants maintain that the

Emergency Act is invalid and there

fore the Ober Bill is not now in effect

as the requisite number of signatures

have been filed with the Secretary of

State for a referendum.

Article 16 of the Maryland Constitu

tion provides for a referendum by the

people, to reject or approve at the polls

any act or part of any act of the

General Assembly. It is not applicable

to appropriations for maintaining the

State Government, and applies to cer

tain portions only of appropriations

for public institutions.

All laws generally tak'e effect on the

first day of June directly succeeding

the date of passage. I f a petition for

a referendum is filed by ten thousand

qualified voters, not more than half

of whom are from Baltimore City, the

law does not take effect until thirty

days after its approval by a majority

of the voters at the next state-wide

election.

Section 2 of Article 16 of the Con

stitution provides that “no law enacted

by the General Assembly shall take

effect until the first day of June next

after the session at which it may be

passed, unless it contains a Section

declaring such law an emergency law

and necessary for the immediate pres

ervation of the public health or safety,

and passed upon a yea and nay vote

supported by three-fifths of all mem

bers elected to each of the two Houses

of the General Assembly. * * *” An

emergency lam remains in force not

withstanding a referendum petition,

but can be repealed by referendum of

the voters in which case the repeal

takes effect thirty days after rejection

by a majority of the voters at the

election. An emergency act shall not

create or abolish any office, or change

the salary, term or duty of any officer.

The Subversive Activities Act of 1949

was approved by the Governor on

March 31, 1949, and became Chapter

86 of the Acts of 1949. Section 3 states

“ that this Act shall take effect June

1, 1949.”

The Emergency Act which became

Chapter 310 of the Acts of 1949 was

approved April 22, 1949, to take imme

diate effect. It did not re-enact the

entire Ober Law. The entire Emer

gency Act is as follows:

“Chapter 310

(Senate Bill 528)

“AN ACT to repeal and re-enact,

with amendments, Section 3 of Chap

ter 86 of the Acts of 1949, said Act

adding Article 85A to the Annotated

Code of Maryland, title “ Sedition and

Subversive Activities,” providing

that said Chapter 86 be declared an

emergency measure.

“ Section 1. Be it enacted by the

General Assembly of Maryland, That

Section 3 of Chapter 86 of the Acts

of 1949, said Act adding Article 85A

to the Annotated Code of Maryland,

title ‘Sedition and Subversive Activi

ties,’ be and it is hereby repealed and

re-enacted, with amendments, to read

as follows:

“3. This Act is hereby declared to

be an emergency measure and neces

sary for the immediate preservation

of the public health and safety, and

having been passed by a yea and

nay vote, supported by three-fifths

of all the members elected to each

of the two Houses of the General

Assembly of Maryland, the same

shall take effect from the date of its

Ijassage.

“Sec. 2. And be it further enacted,

That this Act is hereby declared to

be an emergency measure and neces

sary for the immediate preservation

of the public health and safety, and

having been passed by a yea and nay

3

vote, supported by three-fifths of all

of the members elected to each of

the two Houses of the General As

sembly of Maryland, the same shall

take effect from the date date of its

passage.” Approved April 22, 1949.

The procedure followed by the Gen

eral Assembly to declare the Ober Act

an emergency law was novel. The

usual method is to literally follow the

language of the Constitution as was

done in Chapter 85 of the Acts of 1949,

“ Sabotage Prevention.” Every emer

gency act which the Court has exam

ined (and counsel have not found any

others) contains within itself a provi

sion declaring the act an emergency

measure and necessary for the imme

diate preservation of the public health

and safety, and passed by the requi

site three-fifths of the elected members

of the General Assembly.

In this instance the Legislature

sought to make a whole Act an emerg

ency law, by amending only the sec

tion of the Act setting the date it

becomes effective. The amending sta

tute, Chapter 310, concerns itself only

with Section 3 of Chapter 86.

Section 3 of the original Ober law,

as amended by the Emergency Act,

undertakes to operate retroactively

upon the whole of Chapter 86 and to

declare the entire Ober Act an

emergency measure, and to have been

passed as an emergency measure. Ac

tually the Ober Act was not passed

as an emergency law originally. It

was not repealed and re-enacted as

an emergency act. The explicit provi

sions of the Constitution spell out in

unmistakable words that such an act

becomes effective on June 1st “unless

it contains a Section declaring such

law an emergency law. * * *” “It”

refers clearly and only to the law

sought to be made an emergency act.

Manifestly, Chapter 86, the Ober

Act, does not contain any such section.

So far as the Ober Act itself shows,

it may not have been deemed necessary

for the immediate preservation of the

public health or safety, and it may

not have been passed by the requisite

three-fifths of all the elected members.

A recital in a later Act that the orig

inal Act had been passed by a three-

fifths vote, is, by no means, conclusive

of that fact; nor does a later determi

nation by the legislature that it was

emergency legislation answer the clear

requirement of the Constitution that

no act shall become an emergency act

unless it contain a section so providing.

The 'Emergency Act becomes effective

on April 22, 1949. It contains a provi

sion that the Ober Act becomes effec

tive on the date it (the Ober Act) was

approved, namely, March 31, 1949.

Putting it another way, we have here

one law passed as an emergency law

effective on one date making another

law, not passed as an emergency act,

effective retroactively to an earlier

date.

Counsel for the complainants con

tend this action was taken to delib

erately thwart the will of the people

to prevent a referendum on the Sub

versives Act of 1949. Whatever may

be the reasons, the Court cannot con

sider them. The Court of Appeals has

already spoken flatly on this subject.

In Culp vs. Chestertown, 154 Md.

623, the Court said:

“We deem it advisable, however, to

say in answer to that argument that,

* * * if the legislation does come

within the provisions of Art. 16 of

the Constitution, in that event the

question of whether or not an

emergency in fact exists is a ques

tion for the Legislature, and its de

termination is final and not subject

to review by the courts.”

In Norris vs. Baltimore, 172 Md. at

p. 686, the Court of Appeals again said

that “the Legislature alone has the

power to determine whether such an

emergency as is contemplated by that

section of the Constitution exists, and

its determination of that question is

not judicially reviewable.”

• The Court of Appeals has, however,

held invalid an ordinance of the Mayor

and City Council of Baltimore author

izing a debt as an emergency measure.

Baltimore vs. Hofrichter, 178 Md. 91;

see also Geisendaffer vs. Baltimore,

176 Md. 150.

Complainants contend that the

emergency statute is an ex post facto

law and prohibited by Article 1, Sec

tion 10, of the U. S. Constitution and

Article 17 of the Maryland Declaration

of Bights. An ex post facto law is one

making punishable as a crime what

was not criminal when done. Hoch-

heimer, Criminal Law, fid Ed. p. 102.

Mr. Justice Chase in Calder vs. Bull,

3 Dallas, 386, 1 L. Ed. 648, defined ex

post facto laws, among others, as

“every law that makes an action done

before the passing of the law, and

4

winch was innocent when done, crim

inal ; and punishes such action.”

In this case if we are to follow the

plain meaning of the statutes then

the emergency law creates a crime on

April 22, 1949, and makes it retro

active to March 31, 1949. In Mary

land a statute is not given retroactive

effect unless no other meaning can

be attached or the legislative intent

is clear. (Kelch vs. Keehn, 183 Md.

140; Commission vs. Power Co., 182

Md. 111.)

However, in the second opinion in

Robey vs. Broersma, 181 Md. 325, the

Court of Appeals held that a law

made effective by its terms on May 1st,

but not signed by the Governor until

May 26th, was effective from the latter

date. It might therefore be argued

that while the emergency act purports

to act retroactively, actually it does

not, because both laws are effective

from the date the emergency act was

signed, and no earlier. Such a con

struction would be opposed to the plain

language of the statutes. It is clear

the Legislature meant (and it said)

the Ober Act was to be effective from

the date it was passed.

Anyone violating this law between

March 31st and April 22nd was guilty

of a crime, carrying heavy and severe

penalties, although such a person could

not know until April 22nd that his

earlier act was in fact a violation of

the law.

The general presumptions of validity

of a statute are narrowed in their

scope when we deal with laws limiting-

rights protected by the Constitution.

Statutes dealing with civil rights and

personal liberty are not those referred

to in the dissent of Mr. Justice Car-

dozo in U. S. vs. Constantine, 296 U. S.

287, 299, where he said: “There is

another wise and ancient doctrine that

a court will not adjudge the invalidity

of a statute except for manifest neces

sity. Every reasonable dou-bt must have

been explored and extinguished before

moving to that grave conclusion.”

Rather, they come within the deci

sion of Schneider vs. State, 308 U. S.

147, following the now famous foot

note of Chief Justice Stone in U. S.

vs. Carolena Products Co., 304 U. S.

144, 152, where he said: “there may

be narrower scope for the operation of

the presumption of constitutionality

when legislation appears on its face

to be within a specific prohibition of

the Constitution, such as those of the

first ten amendments, which are

deemed equally specific when held to

be embraced within the Fourteenth

* * See also Duine vs. U. S., 138

F. 2d, 137.

The complainants also maintain that

the Ober Act as amended by the

Emergency Act creates a. new office

and changes the duties of an officer,

which cannot be done by emergency

legislation.

The Subversives Act of 1949 author

izes the Attorney-General to appoint a

Special Assistant Attorney-General in

charge of subversive activities. While

he is under the general supervision of

the Attorney-General, his own special

duties and responsibilities are set out

in detail. He is in charge of subversive

activities, and it is his responsibility,

under the supervision of the Attorney-

General, to work with the State’s At

torneys in this State, submit informa

tion to grand juries, collect evidence

and information, call upon the Super

intendent of State Police, the Police

Commissioner of Baltimore City, and

other police authorities. They in turn

are directed to furnish such informa

tion and assistance as he may request.

The Special Assistant may testify be

fore any grand jury, and he is required

to keep complete information of all

records and matters handled by him.

Such records as may reflect on the

loyalty of any resident may not be

made public except with the permission

of the Attorney-General. Every em

ploying authority who discharges any

one pursuant to the provisions of this

article shall promptly report to the

Special Assistant Attorney-General the

fact of, and the circumstances sur

rounding, the discharge.

In Maryland there is a wide dis

tinction between “office” occupied by

a “public officer” and a “position” oc

cupied by an employee. In Buchholtz

vs. Hill, 178 Md. 280, the Court said:

“The most important characteris

tic of a public office, as distinguished

from any other employment, is the

fact that the incumbent is entrusted

with a part of the sovereign power

to exercise some of the functions of

government for the benefit of the

people. But the necessity of taking

an oath of office is also a very im

portant test in determining whether

a certain position is a public office.”

See also Worcester County vs. Golds-

borough, 90 Md. 103, and State Tax

Commission vs. Harrington, 126 Md.

5

157. In this latter case the Court of

Appeals held that the General Counsel

to the State Tax Commission was a

mere employee and not a public officer.

His salary and tenure of employment

were not fixed by law, no oath was

required, no official bond was given,

no commission was issued, and the in

cumbent did not exercise any sovereign

power. Article 32A, Section 4 of the

Code provides that the Assistants to

the Attorney-General continue in their

employment “during the pleasure of

the Attorney-General.” In Norris vs.

Baltimore, 172 Md. 667, an emergency

law was involved providing for the

use of voting machines and setting up

a special board to carry out the act.

The law was upheld as an emergency

law.

The Court holds that the Special

Assistant Attorney-General is not an

officer holding an office in contraven

tion of the Constitution preventing the

creation o f an office by an emergency

act, nor does the change in the duties

of the Attorney-General violate the

same section of the constitution. That

it will change and alter the work of

the office of Attorney-General is appar

ent. This is inherent in the kind of

activity the Special Assistant will en

gage in. The Ober Commission was

careful to point out that he should not

become a Gestapo agent, and therefore

placed him under the supervision of

the Attorney-General. They were fear

ful, and rightly so, of what could come

out of the creation of such an office,

with power placed in the hands of an

incompetent, narrow, biased official for

getful of the grand traditions of Mary

land.

Conclusions; Emergency Act.

The Court finds that the Emergency

Act, Chapter 310 of the Acts of 1949,

is unconstitutional and invalid, be

cause, it is an ex post facto law and

does not comply with the special pro

visions of the Constitution of Mary

land relating to emergency statutes.

Oaths By Candidates For Office

Section 15 of the Subversive Activi

ties Act provides that no person shall

be a candidate for public office in this

State unless he files an affidavit he

is not a subversive person within the

meaning of this law. The Supervisors

of Elections and the Secretary of State

shall not enter the name on the ballot

or voting machine if the affidavit has

not been filed.

The complainants contend this re

quirement is in violation of Article

37 of the Maryland Declaration of

Rights; “ * * * nor shall the Legisla

ture prescribe any other oath of office

than the oath prescribed by this Con

stitution.” The oath required is set

out in Section 6 of Article 1 of the

Constitution. It is simple; the affiant

swears to support the Constitution of

the United States, be faithful and bear

true allegiance to the State of Mary

land, support the Constitution and

laws thereof, and execute faithfully,

without partiality or prejudice, the

office which he assumes.

The defendants say the Ober Act

does not prescribe any additional oath

of office ; it merely requires a candidate

for office to take a special oath.

The history of these sections of the

Declaration of Rights and of the Con

stitution are interesting and will be

found in “Perlman’s Debates of the

Maryland Constitutional Convention of

1867” and Chief Judge McSherry’s

opinion in Davidson vs. Brice, 91 Md.

6S1.

Beginning with the Declaration of

Rights of the Constitution of 1776, on

through the Constitutions of 1851 and

1864, the Legislature was empowered

to prescribe the oaths of office to be

taken by different officers of govern

ment. Prom 1864 to 1867 the citizens

of this State knew what it meant to

live under a Constitution they did not

approve; one that had gone into effect

by a scant majority of 375 votes, after

“counting” the ballots of soldiers out

In the field. Confederate sympathizers

could not hold office unless restored to

full rights of citizenship by special act

of the General Assembly passed by a

two-thirds vote. ( See Art. 1, Secs. 4, 7,

and 8 of the Constitution of 1864, set

out in full in Perlman’s Debates, etc.,

supra.)

The Constitutional Convention of

1867 swept aside these repressive re

strictions, and introduced a positive

prohibition against any additional

oath. This action was deliberate. As

Chief Judge Me Sherry said: “Thus the

old provision which gave to the Legis

lature the power to exact official oaths

not prescribed by the organic law was

not only deleted, but a new clause

was put in which denied to the Legis

lature the authority it formerly pos

sessed in this particular. Article 37

of the Declaration of Rights is not

confined to offices created by the Con

6

stitution” and “it is wholly immaterial

whether the office he of constitutional

creation or of statutory origin.”

In this case the Court of Appeals

had squarely before it the question

as to whether or not the Legislature

has the authority to prescribe as a

qualification for the office of County

Treasurer any other oath than the one

which Section 6, Article 1, o f the Con

stitution imposes. That Section of the

Constitution was held to be a manda

tory provision. The Court said: “Not

content with prescribing the precise

oath to be taken, the Declaration of

Bights, in Article 37, prohibits any

other oath from being exacted, for it

declares: * * nor shall the Legisla

ture prescribe any oath of office than

the oath prescribed by this Constitu

tion.’ ”

The Subversive Activities Act of

1949 seeks to do by indirection that

which cannot be done directly. It is

obvious that of all the candidates who

file for office, one will be successful.

The law forbids an additional oath

of the elected official. To allow the

oath of all the candidates, knowing

one will be the successfully elected offi

cial, is to nullify the restriction of

Article 37 of the Declaration of Rights.

This is in the face of the plain and

positive inhibition of the law. It

means we no longer look to the sub

stance but adopt the form which de

stroys the substance.

This section of the Ober Act is there

fore invalid.

Constitutionality Of Ober Act.

The question of the validity of the

Subversives Activities Act of 1949 turns

principally on whether it violates the

first, fifth and fourteenth amendments

to the Constitution of the United

States, the Maryland Declaration of

Rights, and our State Constitution.

The complainants say the law is an

unlawful Bill of Attainder, finding

guilt by legislative fiat; that it violates

the freedoms of speech, of the press,

and lawful assembly, creates guilt by

association, and Is obnoxious to our

■whole system of democratic govern

ment. They argue that this act changes

the basic philosophy of our government

from one where the sovereign powrer

lies in a free people, to one where it

would be vested in the governing au

thorities by the device of empowering

them to forcibly control the ideas, ex

pressions and independent political

activities of the people of Maryland.

It is not for the Court to pass on

the wisdom of this or any other legis

lation, nor substitute its judgment or

views for that of the law-making body.

Certain legal principles have been set

down by the Supreme Court and the

Court of Appeals of Maryland; this

Court is bound by those principles as

applied to this statute.

Various anti-sedition laws have been

passed from time to time. In this

country they began with two laws in

1798. The first, the Alien Act, gave

the President power for two years to

expel any alien whom he might deem

“dangerous to the peace and safety of

the United States.” The second, the

Sedition Act, placed heavy penalties

on every person trying to stir up “sedi

tion” or who wrote or published any

thing “false, scandalous or malicious”

against the President, or other officers

of government. The American people

reacted violently against these attacks

on their liberty, and the laws were

never renewed.

Reconstruction days after the Civil

War saw the passage of many laws

depriving citizens of civil rights, and

in Maryland the people hastened to

nullify the Constitution of 1864 by the

Constitution of 1867, now in effect. In

other states laws which constituted

unlawful Bills of Attainder were struck

down by the Supreme Court.

It is usually after wars that such

legislation is passed, engendered by

flames of passion and strong feeling.

In 1918, Congress amended the Es

pionage Act (40 Stat. 553, 1918) by

adding a paragraph by which many

types of utterances could be inter

preted as disloyal. Then followed the

raids by Attorney-General Mitchell.

Palmer and arrests of thousands of

persons, with the subsequent failure

of the prosecutions. (See Chafee, Free

Speech in The United States.)

In 1920 the New York Assembly

suspended without hearing and pend

ing trial five members of the Socialist

Party, alleging this organization was

disloyal. This was followed by the

Lusk Committee of the New York Leg

islature which held many hearings on

the subject of sedition. New York in

1921 enacted the Lusk Anti-Sedition

Bills, establishing standards of loyalty

for teachers and providing for loyalty

tests.

This high intensity of feeling after

the First World War was then fol

lowed by a period of calm, dispassion

7

ate review, then the repeal by Congress

of the amendment it had adopted in

1918, and next in New York by the

repeal of the Lusk Anti-Sedition Sta

tutes. In signing these repealers Gov

ernor Alfred E. Smith said:

“They are repugnant to the funda

mentals of American democracy.

Under the laws repealed, teachers, in

order to exercise their honorable call

ing, were in effect compelled to hold

opinions as to governmental matters

deemed by a State officer consistent

with loyalty. * * * Freedom of opin

ion and freedom of speech were by

these laws unduly shackled. * * *

In signing these bills, I firmly be

lieve that I am vindicating the prin

ciple that, within the limits of the

penal law, every citizen may speak

and teach what he believes.’’

In denouncing the expulsion action

of the New York Assembly, Charles

Evans Hughes, later Chief Justice of

the United States, said: “ it is of the

essence of the institutions of liberty

that it be recognized that guilt is

personal and cannot be attributed to

the holding of opinion or to mere in

tent in the absence of overt actions.

* * *” (5 N. Y. Legis. Doc. No. 30.)

Today we face serious problems to

a degree undreamed of and unknown

before. The situation in Europe and

Asia has brought us face to face with

the realization that the world may be

plunged again into war, of a character

that might destroy civilization as we

know it. Techniques of sedition are

different; unfortunately they have been

successful in too many places for us

to remain complacent. It is clear this

country has powerful enemies outside

its borders. To what extent are they

within our country? How shall they

be ferretted out? What powers have

our legislative bodies to pass laws

aimed at those who threaten us from

within ?

Many penal statutes are now on the

law books dealing with such activities,

as for example, acting as agent of a

foreign government without notifica

tion to the Secretary of State, 18 U.

S. C., section 951; possession of prop

erty in aid of foreign government for

use in violating any penal statute or

treaty rights of the U. S., 18 U. S. C.,

section 957; espionage activities, 18

U. S. 0., sections 793-797; inciting or

aiding rebellion or insurrection, 18 U.

S. C., section 2383; seditious conspir

acy, 18 U. S. C., section 2384; advocat

ing overthrow of the government by

force, 18 U. S. C., section 2385; treason,

18 U. S. 0., section 2381; misprision

of treason, 18 U. S. C., section 2382;

undermining loyalty, discipline or

morale of armed forces, 18 U. S. C.,

section 2387; sabotage, 18 U. S. C.,

section 2156; importing literature ad

vocating treason, insurrection or forci

ble resistance to any federal law, 18

U. S. 0., section 552; injuring federal

property or communications, 18 U. S.

0., section 1361. Organizations en

gaged in civilian military activity, sub

ject to foreign control, affiliated with

a foreign government, or seeking to

overthrow the Government by force,

are subject to registration requirements

under the Voorhis Act, 18 U. S. C.,

2386. And we have the general law of

conspiracy, a, powerful weapon in the

hands of a skilful prosecutor.

With this brief historical discussion,

and some knowledge of present laws,

we now consider the constitutionality

of the Subversive Activities Act of

1949.

Laws abridging freedom of speech,

freedom of the press, or the right of

the people peaceably to assemble, are

forbidden by the first amendment and

to the States by the fourteenth amend

ment. Such laws can be constitution

ally justified only if the utterance, pub

lication or assembly sought to be sup

pressed threatens “clear and present

danger that they will bring about the

substantive evils that Congress has a

right to prevent.” This statement by

Mr. Justice Holmes in Schenck vs. U.

S., 249 U. S. 47, 52, has been repeated

in a series of cases in the Supreme

Court and in Maryland in the recent

case of WFBR. et al. vs. Maryland,

T h e D a ily R ecoed, June 27, 1949. In

that case, Judge Henderson, speaking

for the Court of Appeals, said :

“It is now perfectly clear that

whatever the law of the state, em

bodied in its constitution, statutes

or judicial decisions, the provisions

of the Federal Constitution are su

preme. Bridges vs. California, 314

U. S. 252. It is also clear that the

guarantees contained in the first

amendment, safeguarding free speech

and a free press, are implicit in the

concept of due process contained in

and made applicable to the States

in the fourteenth amendment.”

The Supreme Court has made it clear

that laws may punish acts and conduct

8

which clearly, seriously and imminent

ly threaten substantive evils. They

may not intrude into the realm of

ideas, religious and political beliefs

and opinions. Clear and present danger

refers to proximity and degree. The

law deals with overt acts, not thoughts.

It: may punish for acting, but not for

thinking.

In the dissent of Mr. Justice Holmes

in Abrams vs. U. S., 250 U. S. 616,

630-631 (1919), he said:

“* * * we should be eternally vigi

lant against attempts to check the

expression of opinions that we loathe

and believe to be frought with death,

unless they so imminently threaten

immediate interference with the law

ful and pressing purposes of the law

that an immediate check is required

to save the country. * * * Only the

emergency that makes it immediately

dangerous to leave the correction of

evil counsels to time warrants mak

ing any exception to the sweeping

command ‘Congress shall make no

law abridging the freedom of

speech.’ ”

This is now the law as stated by

the Supreme Court in Schneiderman

vs. U. S., 320 U. S. 118, 138; “ * * * if

there is any principle of the Consti

tution that more imperatively calls for

attachment than any other it is the

principle of free thought—not free

thought for those who agree with us

but freedom for the thought that we

hate.” In this case the Court rejected";

the Government’s contention that a

naturalized citizen who advocated the

principles of the Communist Party was /

not entitled to retain citizenship.

In Bridges vs. Wixon, 326 U. S. 135,

165, Mr. Justice Murphy said;

“Proof that the Communist Party

advocates the theoretical or ultimate -

overthrow of the Government by

force was demonstrated by resort

to some rather ancient party docu

ments, certain other general Com

munist literature and oral corrobo

rating testimony of Government wit

nesses. Not the slightest evidence

was introduced to show that either

Bridges or the Communist Party

seriously and imminently threatens

to uproot the Government by force

or violence.”

Chief Justice Hughes held that the

display of a red flag as a symbol of

opposition by peaceful and legal means

to organized government was protected

by the free speech guaranties of the

Constitution. (Stromberg vs. Califor

nia, 283 U. S. 359.) The Supreme Court

has upheld the right of persons to as

semble at a public meeting under the

auspices of the Communist Party. (He

Jonge vs. Oregon, 299 TJ. S. 353.) In

Harndon vs. Lowry, 301 U. S. 242, a

statute restricting (as construed) the

right to a Communist to solicit mem

bership in the Communist Party was

held invalid. In Thornhill vs. Ala

bama, 310 U. S. 97, the Court said:

“The existence of such a statute, which

readily lends itself to harsh and dis

criminatory enforcement by local prose

cuting officials, against particular

groups deemed to merit their dis

pleasure, results in a continuous and

pervasive restraint on all freedom of

discussion that might reasonably be

regarded as within its purview.”

Recently, in Terminiello vs. Chicago,

337 U. S. 1, 4, Mr. Justice Douglas

said:

“ » * * right to speak freely

and to promote diversity of ideas

and programs is therefore one of the

chief distinctions that sets us apart;

from totalitarian regimes. Accord

ingly a function of free speech under

our system of government is to in

vite dispute. It may indeed best:

serve its high purpose when it in

duces a condition of unrest, creates ;

dissatisfaction with conditions as

they are, or even stirs people to

anger. Speech is often provocative;

and challenging. It may strike at -

prejudices and preconceptions and

have profound unsettling effects as it

presses for acceptance of an idea. :

* * * There is no room under our Con

stitution for a more restrictive view. 5

Por the alternative would lead to

standardization of ideas either by

legislatures, courts, or dominant poli

tical or community groups.”

The Ober Act is a penal statute car

rying severe and drastic penalties.

Statutes creating crimes are invalid

if they define the crime in vague and

ambiguous terms. If a law is indefinite

and uncertain it fails to meet the con

stitutional requirement of due process

as in Winters vs. New York, 333 D. S.

507, 515, where the Court said: “The

standards of certainty in statutes pun

ishing for offenses is higher than in

those depending primarily upon civil

sanction for enforcement. The crime

must be defined with appropriate defi

9

niteness * * * there must be ascertain

able standards of guilt. Men of com

mon intelligence cannot be required to

guess at the meaning of the enactment.

The vagueness may be from uncertain

ty in regard to persons within the scope

of the act, * * * or in regard to the

applicable tests to ascertain guilt.”

And at page 518 the Court said:

“ * * * Tjie present case as to a vague

statute abridging free speech involves

the circulation of only vulgar maga

zines. The next may call for decision

as to free expression of political views

in the light of a statute intended to

punish subversive activities.”

The Ober Act makes it a felony by

the use of general language for any

person knowingly and wilfully to act,

advocate or teach “by any means’’ the

commission of any act as to constitute

a clear and present danger to the

security of the United States, Mary

land, or any political subdivision, or

participate in the management or con

tribute to support of any subversive

organization. This would Include any

attempt to bring about such a result

by speech, pamphlet, publication, radio

discussion, or participating in a meet

ing designed to bring about changes in

our government.

Crimes must be definitely defined.

What is meant by “alteration” of the

constitutional form of the Government

of the United States? There are some

who believe in the Socialist form of

government and advocate that this

country adopt the system of govern

ment in force in England today. To

them revolution means the consumma

tion of the change; it does not include

force or violence. This may seem far

fetched, but the test of the constitu

tionality of a statute ordinarily is

not what has happened, but what may

happen under it. (Raney vs. Montgom

ery County, 170 Md. 196.)

This statute makes it a felony to

remain a member of a subversive or

ganization after September 1, 1949,

knowing the organization to be sub

versive. Does “knowing” mean actual

knowledge, or constructive knowledge?

Does it mean having the information

in one’s possession to lead a reasonable

person to believe the organization is

subversive? May reasonable persons

differ on the meaning or interpretation

of such information?

If a member honestly believes he

belongs to an organization that is not

subversive, he may find himself facing

severe, even harsh penalties, if that

organization has been found to be sub

versive under Section 5 of the Act by

a court of competent jurisdiction. It

is then too late to withdraw from mem

bership.

Some labor organizations have been

characterized as subversive. A worker

may believe his union is in the con

trol of officers who would direct its

activities into seditious channels. If

that union has a closed-shop agreement

with management he cannot withdraw

from the organization without losing

his job. If he remains in the union, he

is guilty of a felony, not because of

any act of commission on his part, but

because of his association with others.

Valuable property rights within the or

ganization may be lost; the alternative

is no job, or conviction of a serious

crime, all without his day in court, and

without due process.

An organization, legal when founded,

may become subversive within the

meaning of this law, as a result of

acts by a small group of officers in

control for a short time, and in spite

of the violent opposition of the general

membership.

If it be a political party that is de

clared subversive, what tests shall be

applied to determine whether one is

a “member” of the party? How does

one determine who is a member of the

Democratic or Republican party? Po

litical parties do not take applications

for membership; individuals do not

swear their adherence to the party’s

platform. Suppose such an organiza

tion does have characteristics of mem

bership which require a card or other

symbol of membership and immediately

upon passage of this bill abolishes such

indicia of membership, how then would

one determine what constitutes mem

bership?

In the case of Bridges vs. Wixom,

326 U. S. 135, 143, supra, the Supreme

Court distinguished between “member

ship” and “affiliation.” Does member

ship mean making speeches on behalf

of candidates of a party? attendance

at meetings? If this act means the

Communist Party, the Supreme Court

has said that such participation in the

affairs of the Communist Party does

not necessarily indicate adherence to

any purpose to overthrow the Govern

ment of the United States hy force and

violence or subserviance to the policies

of a foreign government—Schneider-

man vs. U. S., 320 U. S. 118, supra.

There the Court said, at p. 136: “Un

der our traditions beliefs are personal

and not a matter of mere association,

and men in adhering to a political

party or other organization notoriously

do not subscribe unqualifiedly to all

of its platforms or asserted principles.”

In the loyalty section of the statute

no subversive person is eligible to hold

any kind of office or position in the

State Government or any political sub

division. All employers must establish

rules and regulations and procedures

to ascertain if any person, including

teachers, is a subversive person “and

that there are no reasonable grounds

to believe such persons are subversive

persons. In the event such reasonable

grounds exist, he or she, as the case

may be, shall not be appointed or em

ployed.”

What kind of standard is set up by

“ reasonable grounds?” What may seem

reasonable to one may seem extremely

arbitrary and unreasonable to another.

Here the employer need not have evi

dence that the prospective employee is

subversive. All he needs is reasonable

grounds. No man may be convicted of

a crime in Maryland except upon evi

dence; the court and jury must be con

vinced beyond a reasonable doubt,

based upon the evidence. In civil cases

it is the preponderance of the evidence.

Under this statute one may be deprived

of an opportunity to work for the state,

county or city upon no evidence at all,

but merely upon “reasonable grounds.”

In the Schneiderman case, supra, the

Supreme Court held that cancellation

of the naturalization of a member of

the Communist Party was illegal be

cause the law required “clear, un

equivocal and convincing evidence.”

The Court said, p. 153: “We are not

concerned with the question -whether

a reasonable man might so conclude,

nor with the narrow issue whether

administrative findings to that effect

are so lacking in evidentiary support

as to amount to a denial of due pro

cess.”

Every person who is employed by

the State of Maryland is required to

sign a written notice, subject to the

penalties of perjury, that he is not a

subversive person or a member of any

subversive organization. All who re

fuse to execute such a statement shall

immediately be discharged, even

though the refusal is based on con

scientious scruples against taking such

an oath.

“Reasonable grounds on all the evi

dence to believe that any person is a

subversive person” is cause for dis

charge. While the loss of a position

is purely civil, the discharge must be

reported to the Special Assistant At

torney-General in charge of subversive

activities. So one may lose his job

after many years of honorable service

in the State’s employ, if he is a mem

ber of an organization that started out

innocently enough, but found its aims

prostituted by its officers. The fact

that he attended no meetings, showed

no interest in its affairs, perhaps did

not even pay dues, may not save him

from the loss of his job if he was

carried on the roster of membership.

Such a fact may be “reasonable grounds

on all the evidence.”

The definition of foreign subversive

organizations brings in another vague

term. It “means any organization

directed, dominated or controlled

directly or indirectly by a foreign gov

ernment * * *” What does “indirectly”

mean ? To ask the question is to answer

it. This is so vague and indefinite as

not to meet the requirements of a

penal statute. Does “indirect” mean

that the organization is a foreign sub

versive organization when it changes

with the party line as given out at

Moscow? or if it opposes the Atlantic

Pact? or the Marshall Plan? or the

foreign policy of this country? or has

connections with, or is affiliated with,

international labor organizations whose

policies may be “indirectly” controlled

from England or Canada? What be

comes of the status of a dissenting

member? a minority of members? or

even a majority who differ with the

officers?

It may well be that what this statute

seeks to accomplish is difficult under

our law. In Musser vs. Utah, 333 U. S.

95, 97, the Supreme Court said: “This

led to the inquiry as to whether the

statute attempts to cover so much that

it effectively covers nothing. Statutes

defining crimes may fail of their pur

pose if they do not provide some

reasonable standards of guilt. * * *

Legislation may run afoul of the Due

Process Clause because it fails to give

adequate guidance to those who would

be law-abiding, to advise defendants

of the nature of the offense with which

they are charged, or to guide courts

in trying those who are accused.”

Every public school teacher must

take a loyalty oath. State aided insti

l l

tutions of learning must purge their

institutions of subversive persons

within the meaning of the Act. To de

termine if such statutes are clear and

precise in their terms or vague and

indefinite, one need only turn to the

debates now being waged in academic

circles on this very issue.

There are some who, although im

placable foes of Communism, feel that

so long as membership in the Com

munist Party is legal, that faculty

members should not be deprived of

their positions. Others hold that mem

bership in the Communist Party is in

compatible with academic competence

and integrity. There are some who

even believe professors should be dis

ciplined if they lend their presence

and give encouragement to extra-cur

ricular activities regarded as com

munistic in leaning, if not in fact.

The Ober Act refers to the “World

Communist Movement” and inferential-

ly to the Communist Party. It is

charged by the complainants in this

case that the act means members of

the Communist Party as well as lib

erals, labor organizations, political

parties other than the Democratic and

Republican Parties; any and all who

differ from the generally accepted be

liefs of those who happen to be in the

majority at the moment. They charge

that this is a Bill of Attainder and

unconstitutional.

In Anderson vs. Baker, 23 Md. 531,

604, the Court of Appeals defined Bills

of Attainder. It said:

“Bills of attainder, which include

bills of pains and penalties, are pro

hibited as well by the Constitution

of Maryland, (Art. 18, Declaration

of Rights,) as by the Constitution of

the United States. They are special

Acts of the Legislature, inflicting

capital or other punishments upon

persons supposed to be guilty of an

offense, without any conviction in

the ordinary course of judicial pro

ceedings. In such cases, the Legisla

ture assumes judicial magistracy,

pronouncing upon the guilt of the

party without any of the common

forms and guards of trial, and satis

fying itself with proofs, when within

its reach, whether conformable to the

rules of evidence or not.”

In U. S. vs. Lovett, 328 U. S. 303,

the Supreme Court, after reviewing its

prior decisions on Bills of Attainder,

said, at p. 315 :

“ * * * They stand for the proposi

tion that legislative acts, no matter

what their form, that apply either

to named individuals or to easily as

certainable members of a group in

such a way as to inflict punishment

on them without a judicial trial are

bills of attainder prohibited by the

Constitution.”

In that case certain government em

ployees were charged by a Congres

sional Committee with subversive be

liefs and subversive associations. A

rider was attached to the Appropria

tions Bill depriving them of further

pay. The Court said, p. 316:

“ * * * The fact that the punish

ment is inflicted through the instru

mentality of an Act specifically cut

ting off the pay of certain named in

dividuals found guilty of disloyalty,

makes it no less galling or effective

than if it had been done by an Act

which designated the conduct as

criminal. No one would think that

Congress could have passed a valid

law, stating that after investigation

it had found Lovett, Dodd, and Wat

son ‘guilty’ of the crime of engaging

in ‘subversive activities’, defined that

term for the first time, and sentenced

them to perpetual exclusion from any

government employment. Section

304, while it does not use that lan

guage, accomplishes that result. The

effect was to inflict punishment with

out the safeguards of a judicial trial

and ‘determined by no previous law

or fixed rule’. The Constitution de

clares that that cannot be done either

by a State or by the United States.”

The Supreme Court cited Cummings

vs. Missouri, 4 Wall (U. S.) 217, where

a Catholic priest was convicted for

teaching and preaching without taking

the oath of loyalty as provided by the

Missouri (Reconstruction) Constitu

tion. The conviction was set aside, the

constitutional provision struck down

as an unlawful Bill of Attainder. The

Court said that case has never been

overruled—it is still the law.

Conclusion.

The Subversive Activities Act of

1949 for the reasons stated is uncon

stitutional and invalid. It violates

the basic freedoms guaranteed by the

first and fourteenth amendments, and

due process under the fifth amendment.

It violates the Maryland Constitution

and Declaration of Rights, is an un

lawful Bill of Attainder, and is too

12

general for a penal statute. As stated

by Mr. Justice Jackson in West Vir

ginia Board vs. Barnette, 319 U. S.

624, 642: “If there is any fixed star

in our constitutional constellation, it

is that no official, high or petty, can

prescribe what shall be orthodox in

politics, nationalism, religion, or other

matters of opinion or force citizens to

confess by word or act their faith

therein.”

The demurrers will be overruled.

IN THE CIRCUIT COURT NO. 2

OF BALTIMORE CITY

No. 30056-A Docket 58A, 224 (1949)

PHILIP FRANKFELD AND GEORGE

A. MEYERS,

vs.

HALL HAMMOND, ATTORNEY-

GENERAL, ET AL.

Maurice Braverman for complain

ants.

Hall Hammond, Attorney-General;

J. Edgar Harvey, Deputy Attorney-

General; Thomas N. Biddison, City

Solicitor of Baltimore; Leroy W. Pres-

ton and Hugo A. Riccuiti, Assistant

City Solicitors, for the defendants.

Philip Frankfeld, Chairman of the

Communist Party of Maryland, and

George A. Meyers, labor secretary of

the Communist Party, filed this Bill of

Complaint following in the main the

allegations in the case of Lancaster,

et al., just decided. In addition, they

filed as an exhibit a copy of the Con

stitution of the Communist Party of

the United States, and set out the

various aims of this organization.

For the reasons given in the Lan

caster case, the demurrers will be

overruled.

(Reprinted from T h e D a ily R ecord, August 16, 191/9)

13