Gillespie v. US Steel Corporation Court Opinion

Unannotated Secondary Research

December 7, 1964

10 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Working Files. Gillespie v. US Steel Corporation Court Opinion, 1964. 53f5e1b1-54e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d242634f-212d-449b-b2bc-0ef2b2fef468/gillespie-v-us-steel-corporation-court-opinion. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

* i<J *=.*.**• J> t/L. s is S.-v< ^ ? -*. tv * * « - * - l‘ f r t f i r& r f * . *# y*t - ******** ft »< « t 1.** O* *«A -*

199

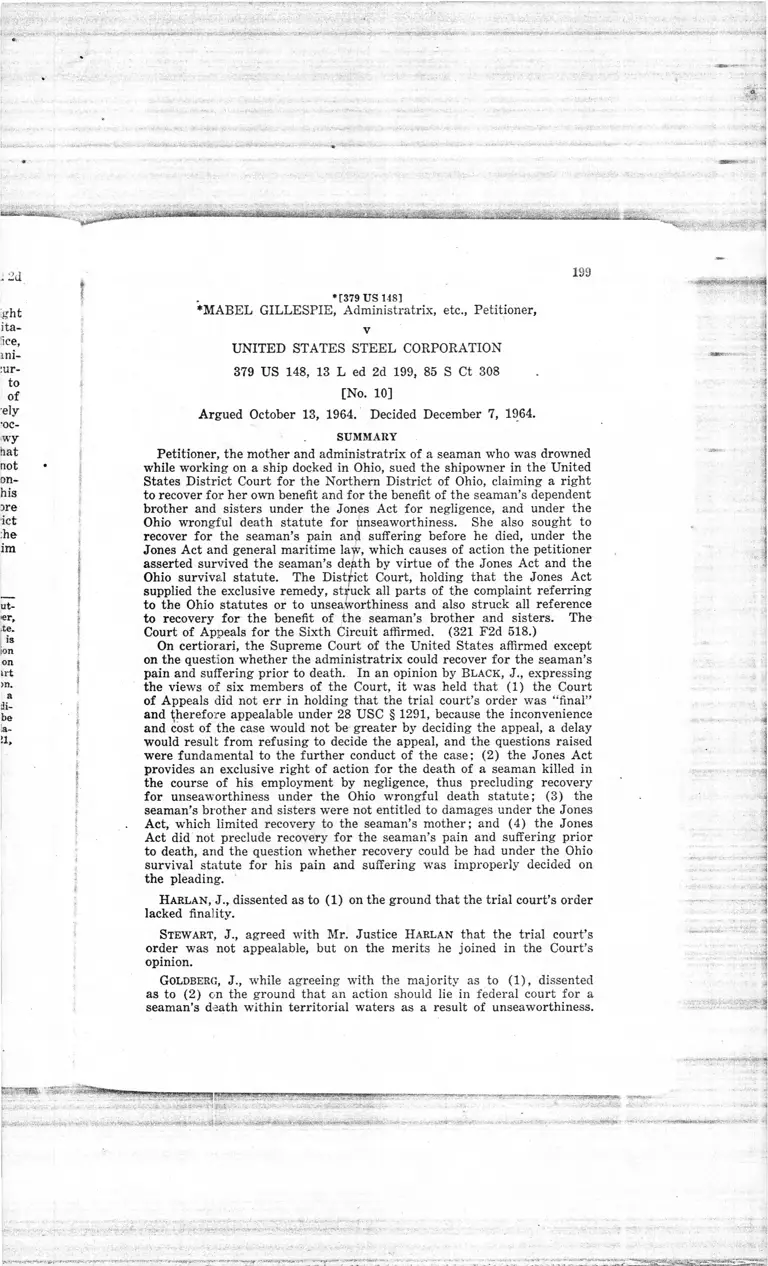

. *[379 US 148]

*MABEL GILLESPIE, Administratrix, etc., Petitioner,

v

UNITED STATES STEEL CORPORATION

379 US 148, 13 L ed 2d 199, 85 S Ct 308 .

[No. 10]

Argued October 13, 1964. Decided December 7, 1964.

. SUMMARY

Petitioner, the mother and administratrix of a seaman who was drowned

while working on a ship docked in Ohio, sued the shipowner in the United

States District Court for the Northern District of Ohio, claiming a right

to recover for her own benefit and for the benefit of the seaman’s dependent

brother and sisters under the Jones Act for negligence, and under the

Ohio wrongful death statute for unseaworthiness. She also sought to

recover for the seaman’s pain and suffering before he died, under the

Jones Act and general maritime law, which causes of action the petitioner

asserted survived the seaman’s death by virtue of the Jones Act and the

Ohio survival statute. The District Court, holding that the Jones Act

supplied the exclusive remedy, struck all parts of the complaint referring

to the Ohio statutes or to unseaworthiness and also struck all reference

to recovery for the benefit of the seaman’s brother and sisters. The

Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit affirmed. (321 F2d 518.)

On certiorari, the Supreme Court of the United States affirmed except

on the question whether the administratrix could recover for the seaman’s

pain and suffering prior to death. In an opinion by Black, J., expressing

the views of six members of the Court, it was held that (1) the Court

of Appeals did not err in holding that the trial court’s order was “ final”

and therefore appealable under 28 USC § 1291, because the inconvenience

and cost of the case would not be greater by deciding the appeal, a delay

would result from refusing to decide the appeal, and the questions raised

were fundamental to the further conduct of the case; (2) the Jones Act

provides an exclusive right of action for the death of a seaman killed in

the course of his employment by negligence, thus precluding recovery

for unseaworthiness under the Ohio wrongful death statute; (3) the

seaman’s brother and sisters were not entitled to damages under the Jones

Act, which limited recovery to the seaman’s mother; and (4) the Jones

Act did not; preclude recovery for the seaman’s pain and suffering prior

to death, and the question whether recovery could be had under the Ohio

survival statute for his pain and suffering wras improperly decided on

the pleading.

Harlan, J., dissented as to (1) on the ground that the trial court’s order

lacked finality.

Stewart, J., agreed with Mr. Justice Harlan that the trial court’s

order was not appealable, but on the merits he joined in the Court’s

opinion.

Goldberg, J., while agreeing with the majority as to (1 ), dissented

as to (2) on the ground that an action should lie in federal court for a

seaman’s death wdthin territorial waters as a result of unseaworthiness.

: ■■ -■ • .

■■

GILLESPIE v UNITED STATES STEEL CORP.

379 US 148, 13 L ed 2d 199, 85 S Ct 308 201

otherwise be- applied to maritime

deaths and precluding any possible

recovery for death based on a theory

of unseaworthiness.

Master and Servant § 55; Seamen § 15

— seaman’s death — beneficiaries

of recovery

6. Recovery under the Jones Act

(46 USC § 688) for the death of a

seaman depends on § 1 of the Federal

Employers’ Liability Act (45 USC § 1),

which limits liability to one of three

statutory classes of possible benefi

ciaries and does not create liability

to the several classes collectively; con

sequently, the Jones Act does not pro

vide for damages for a seaman’s death

for the benefit of the seaman’s brother

and sisters as well as for his mother.

Seamen § 15 — negligence action —

survival

7. Through § 9 of the Federal Em

ployers’ Liability Act (45 USC § 59),

the Jones Act (46 USC § 688) provides

for the survival after a seaman’s death

of his claim based on a theory of neg

ligence.

Abatement and Revival §9 ; Pleading

§ 48 — seaman’s right of action —

pain and suffering

8. A Federal Court of Appeals errs

in deciding on the basis of an admin

istratrix’s pleading alone that the

right of her decedent, a seaman, to

recover for unseaworthiness causing

pain and suffering before his death did;

not survive under a state survival

statute.

[See annotation p. 1013, infra]

Points from Separate Opinion

Appeal and Error § 31 — interlocutory

orders — statute permitting ap

peal — purpose

9. The purpose of 28 USC § 1292(b),

which permits Federal Courts of Ap

peals to review interlocutory orders

made under certain circumstances, is

to permit a Federal District Judge, in

his discretion, to obtain immediate

reyiew of an order which might con

trol the further conduct of the case

and which normally involves an unset

tled question of law. [From separate

opinion of Harlan, J.]

Appeal and Error §1361; Judgment

I § 71 — dismissal of cause of ac

tion — merger of claims

10. In a suit for recovery under the

Jones Act (46 USC § 688) and general

maritime law, wherein the trial court

strikes the claim for unseaworthiness

under general maritime law and the

cause proceeds to trial, the asserted

claim for unseaworthiness merges in

the judgment if at the trial the plain

tiff wins, and is preserved for appeal

if at the trial the plaintiff loses on

the Jones Act claim. [From separate

opinion of Harlan, J.]

BRIEFS AND APPEARANCES OF COUNSEL

Jack G. Day argued the cause for petitioner.

Thomas V. Koykka argued the cause for respondent.

Briefs of Counsel, p 1010, infra.

OPINION OF

*[379 US 149]

*Mr. Justice Black delivered the

opinion of the Court.

The petitioner, administratrix of

the estate of her son Daniel Gilles

pie, brought this action in federal

court against the respondent ship-

*[379 US 1591

owner-employer to recover ♦dam

ages for Gillespie’s death, which was

THE COURT

alleged to have occurred when he fell

and was drowned while working as

a seaman on respondent’s ship

docked in Ohio. She claimed a right

to recover for the benefit of herself

and of the decedent’s dependent

brother and sisters under the Jones

Act, which subjects employers to

liability if by negligence they cause

a seaman’s injury or death.1 She

1. 41 st3t 1007, 46 USC § 688 (1958 ed); injury in the course of his employment

Any seaman who shall suffer personal may, at his election, maintain an action

, . . - ........................... «*?

' ' ^ , V . r

' •-.S- -

•■>•*..-<• -v** »•***■/> ■Xs&&& ■■■ -- ••'■ Jsfe*fewsasa&>»

201 U. S. SUPREME COURT REPORTS 13 L ed 2d

also claimed a right of recovery un

der the Ohio wrongful death stat

ute8 because the vessel allegedly was

not seaworthy as required by the

“ general maritime law.” The com

plaint in addition sought damages

for Gillespie’s pain and suffering be

fore he died, based on the Jones Act

and the general maritime law,

causes of action which petitioner

said survived Gillespie’s death by

force of the Jones Act itself and the

Ohio survival statute,3 respectively.

The District Judge, holding that the

Jones Act supplied the exclusive

remedy, on motion of respondent

struck all parts of the complaint

which referred to the Ohio statutes

or to unseaworthiness. He also

struck all reference to recovery for

the benefit of the brother and sis-j

ters of the decedent, who respond-

*[379 US 151]

ent had argued, were *not benel

ciaries entitled to recovery under

the Jones Act while their mother

was living.

Petitioner immediately appealed

to the Court of Appeals. Respond

ent moved to dismiss the appeal on

the ground that the ruling appealed

from Was not a “ final” decision of

the District Court as required by 28

USC § 1291 (1958 ed).4 Thereupon

petitioner administratrix, this time

joined by the brother and sisters,

filed in the Court of Appeals a peti

tion for mandamus or other appro

priate writ commanding the District

Judge to vacate his original order

and enter a new one either denying

the motion to strike or in the alter

native granting the motion but in

cluding also “ the requisite written

statement to effectively render his

said order appealable within the

provisions of 28 USCA § 1292 (b ),”

a statute providing for appeal of

certain interlocutory orders.6 With

out definitely deciding whether

mandamus would have been appro

priate in this case or deciding the

“ close” question of appealability,

the Court of Appeals proceeded to

determine the controversy “ on the

merits as though it were submitted

on an appeal” ;6 this the court said

*[379 US 152]

it felt free to *do since its resolution

of the merits did not prejudice re

spondent in any way, because it

sustained respondent’s contentions

by denying the petition for manda

mus and affirming the District

for damages at law, with the right of trial

by jury, and in such action all statutes

of the United States modifying or extend

ing the common-law right or remedy in

cases of personal injury to railway em

ployees shall apply; and in case of the

death of any seaman as a result of any

such personal injury the personal repre

sentative of such seaman may maintain an

action for damages at law with the right

of trial by jury, and in such action all

statutes of the United States conferring

or regulating the right of action for death

in the case of railway employees shall be

applicable. Jurisdiction in such actions

shall he under the court of the district in

which the defendant employer resides or

in which his principal office is located.”

2. Ohio Rev Code § 2125.01.

3. Ohio Rev Code § 2305.21.

4. “The courts of appeals shall have

jurisdiction of appeals from all final deci

sions of the district courts of the United

States . . . except where a direct

review may be had in the Supreme Court. ’

5. Section 1292(b) provides:

“When a district judge, in making in a

civil action an order not otherwise appeal

able under this section, shall be of the

opinion that such order involves a con

trolling Question of law as to which there

is substantial ground for difference of opin

ion and that an immediate appeal from

the order may materially advance the ulti

mate termination of the litigation, ne shall

so state in writing in such order. The

Court of Appeals may thereupon, in its

discretion, permit an appeal to be taken

from such order, if application is made

to it within ten days after the entry of

the order: Provided, however, That appli

cation for an appeal hereunder shall not

stay proceedings in the district court un

less the district judge or the Court of

Appeals or a judge thereof shall so order.

6. 321 F2d 518, 532.

.....................^

, ■ • - . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ' . . . .

■ •

• • • ■

; r : -:* " ^ ......... ' * ? '' •’

i

•I

l

i

|.

I-

l

5

t

I'

S'-

I

i

k1

!

GILLESPIE v UNITED STATES STEEL CORP. 203

379 US 148, 13 L ed

Court’s order.7 321 F2d 518. Peti

tioner brought the case here, and

we granted certiorari. 375 US 962,

11 L ed 2d 413, 84 S Ct 487.

I.

[1-41 In this Court respondent

joins petitioner in urging us to

hold that 28 USC § 1291 (1958 ed.)

does not require us to dismiss this

case and that we can and should

decide the validity of the District

Court’s order to strike. We agree.

Under § 1291 an appeal may be

taken from any “ final” order of

a district court. But as this Court

often has pointed out, a decision

“ final” within the meaning of §

1291 does not necessarily mean the

last order possible to be made in

a case. Cohen v Beneficial Indus

trial Loan Corp. 337 US 541, 545,

93 L ed 1528, 1535, 69 S Ct 1221.

And our cases long have recognized

that whether a ruling is “ final”

within the meaning of § 1291 is fre

quently so close a question that

decision of that issue either way

can be supported with equally force

ful arguments, and that it is impos

sible to devise a formula to resolve

all marginal cases coming within

what might well be called the “ twi

light zone” of finality. Because of

this difficulty this Court has held

that the requirement of finality is to

be given a “practical rather than a

technical construction.” Cohen v

Beneficial Industrial Loan Corp., su

pra, 337 US, at 546, 93 L ed at 1536.

See also Brown Shoe Co. v United

States, 370 US 294, 306, 8 L ed 2d

510, 524, 82 S Ct 1502; Bronson v

Railroad Co. 2 Black 524, 531, 17

L ed 347, 360; Forgay v Conrad, 6

How 201, 203, 12 L ed 404, 405.

Dickinson v Petroleum Conversion

Corp. 338 US 507, 511, 94 L ed 299,

302, 70 S Ct 322, pointed out that in

7. No review is sought in this Court of

the denial of the petition for mandamus.

2d 199, 85 S Ct 308

deciding the question of finality the

most important competing consid

erations are “ the inconvenience and

*[379 US 153]

costs *or piecemeal review on the

one hand and the danger of denying

justice by delay on the other.”

Such competing considerations are

shown by the record in the case be

fore us. It is true that the review

of this case by the Court of Appeals

could be called “ piecemeal” ; but it

does not appear that the inconven

ience and cost of trying this case

will be greater because the Court

of Appeals decided the issues raised

instead of compelling the parties to

go to trial with them unanswered.

We cannot say that the Court of

Appeals chose wrongly under the

circumstances. And it seems clear

now that the case is before us that

the eventual costs, as all the parties

recognize, will certainly be less if

we now pass on the questions pre

sented here rather than send the

case back with those issues unde

cided. Moreover, delay of perhaps

a number of years in having the

brother’s and sisters’ rights deter

mined might work a great injustice

on them, since the claims for recov

ery for their benefit have been ef

fectively cut oif so long as the Dis

trict Judge’s ruling stands. And

while their claims are not formally

severable so as to make the court’s

order unquestionably appealable as

to them, cf. Dickinson v Petroleum

Conversion Corp., supra, there cer

tainly is ample reason to view their

claims as severable in deciding the

issue of finality, particularly since

the brother and sisters were sepa

rate parties in the petition for ex

traordinary relief. Cf. Swift & Co.

Packers v Compania Colombiana Del

Caribe, S. A., 339 US 684, 688-689,

94 L ed 1206, 1210, 1211, 70 S Ct

861, 19 ALR2d 630; Gumbel v Pit

kin, 113 US 545, 548, 28 L ed 1128,

1129, 5 S Ct 616. Furthermore, in

- :

.

.

•- -..... 4

. . - ,-T

■ -

---~r—' r?

■ ■ ^‘ ... •*■**- Mi

____• : .: 3|

■ '1

.̂ vivW*W • .."**••***

te • - — - ■ •• ■ ' ’ ' .

- ---- V”"’ ' '■ -

■ : ■ ■ . ■ ■ ■

. ' . ft

• - ' ■

- . . . .. i

■■ . ■

- - *J -'■'f ’¥>, — , V-Jf***.’1- wuaJ&L i*. ■ m

A• ' ■. - i: ' ■ f i . ; - ■■■•. ' i

j]

h

11

\

V:

-

•• ... ; -•• : >*tjf

'

. ;j.

U. S. SUPREME COURT REPORTS 13 Led 2d

United States v General Motors

Corp. 323 US 373, 377, 89 L ed 311,

318, 65 S Ct 357, 156 ALR 390, this

Court contrary to its usual practice

reviewed a trial court’s refusal to

permit proof of certain items of

damages in a case not yet fully

tried, because the ruling was “ fun

damental to the further conduct of

the case.” For these same reasons

this Court reviewed such a ruling

in Land v Dollar, 330 US 731, 734,

note 2, 91 L ed 1209, 1214, 67 S Ct

*[379 US 154]

1009, and Larson v Domestic *& For

eign Commerce Corp. 337 US 682,

685, note 3, 93 L ed 1628, 1633, 69 S

Ct 1457, where, as here, the case

had not yet been fully tried. And

see Cohen v Beneficial Industrial

Loan Corp., supra, 337 US, at 545

547, 93 L ed at 1535, 1536. We

think that the questions presented

here are equally “ fundamental to

the further conduct of the case.”

It is true that if the District Judge

had certified the case to the Court of

Appeals under 28 USC § 1292(b)

^1958 ed.), the appeal unquestion

ably would have been proper; in

light of the circumstances we be

lieve that the Court of Appeals

properly implemented the same pol

icy Congress sought to promote in

§ 1292 (b) by treating this obviously

marginal case as final and appeal

able under 28 USC § 1291 (1958

ed.). We therefore proceed to con

sider the correctness of the Court

of Appeals’ judgment.

. ^ II.

[ 5 ] In 1930 this Court held in

Lindgren v United States, 281 US

~ sT se e , e. g., The Tungus v Skovgaard,

358 US 588, 595, note 9, 3 L ed 2d 524,

79 S Ct 503, 71 ALR2d 1280; Pope &

Talbot, Inc. v Hawn, 346 US 406, 98 L ed

143 74 S Ct 202; Seas Shipping Co. v

Sieracki, 328 US 85, 90 L ed 1099, 66 S Ct

872; Mahnich v Southern S.S. Co. 321 US

96, 88 L ed 561, 64 S Ct 455.

-9. Chelentis v Luekenbach S.S. Co, 247

US 372, 62 L ed 1171, 38 S Ct. 501, 19

38, 74 L ed 686, 50 S Ct 207, that in

passing § 33 of the Merchant Ma

rine Act 1920, now 46 USC § 688

(1958 ed.), commonly called the

Jones Act, Congress provided an

exclusive right of action for the

death of seamen killed in the course

of their employment, superseding

all death statutes which might

otherwise be applied to maritime

deaths, and, since the Act gave

recovery only for negligence, pre

cluding any possible recovery based

on a theory of unseaworthiness.

A strong appeal is now made that

we overrule Lindgren because it

is said to be unfair and incon

gruous in the light of some of

our later cases which have liberal

ized the rights of seamen and

nonseamen to recover on a theory

of unseaworthiness for injuries,

though not for death.8 No one of

these cases, however, has cast doubt

on the correctness of the interpreta-

*[379 US 155]

tion *of the Jones Act in Lindgren,

based as it was on a careful study

of the Act in the context of then-

existing admiralty principles, ̂ deci

sions and statutes. The opinion in

Lindgren particularly pointed out

that prior to the Jones Act there

had existed no federal right of ac

tion by statute or under the general

maritime law to recover damages

for wrongful death of a seaman,9

though some of the States did by

statute authorize a right of recov

ery which admiralty would en

force.10 Congress, the Lindgren

Court held, passed the Jones Act in

order to give a uniform right of

recovery for the death of every sea-

NCCA 309; The Harrisburg, 119 US 199,

30 L ed 358, 7 S Ct 140; cf. The Osceola,

189 US 158, 47 L ed 760, 23 S Ct 483.

10. Great Lakes Dredge & Dock Co. v

Kierejewski, 261 US 479, 67 L ed 756, 43

S Ct 418; Western Fuel Co. v Garcia, 25'

US 233, 66 L ed 210, 42 S Ct 89; cf. Th

Hamilton, 207 US 398, 52 L ed 264, 2:

S Ct 133.

man. 1

on to a

line A*

tion in

uniforn

rally j

Constit

sedes *

statute

281 U;

Thirty-

the Lit

has let

the ini

it. Tl;

one tl

rented]

seamei

is pro\

the F

Act.11

special

rules ;

not Lc'

turb t'

liabilit

Act.

[6]

that e’

dy for

the Di

to hoh

for da

fit of

the d

mothe

any, s'

45 US

vides

death

the su

aU:i i„

none,

cuts;

of IT

plover

i i . a

S§st~4

. . . ' ' W : .'

; . . . . . . . ■ . . . . . ' . ■ ■ ■ ■

.

. , .. ... . .. . . . . . ;:.:....... .. . . . . . . . .■ — . .0 . . . * . . . . . . . . .... .. ■ ~ . ................. .. . . . : ................... .. ..

. . - ■ . • ■ . ■ ■ : ..-;'-.'.u;.:..' ....>*..■■■'■' v : ;, -V ■-. - ■ > ;• s -,v -vats!

..... .-....V-

GILLESPIE v UNITED

; 379 US 148, 13 L ed

man. “ It W plain,” the Court went

on to say, “ that the Merchant Ma

rine Act is one of general applica

tion intended to bring about the

uniformity in the exercise of admi

ralty jurisdiction required by the

Constitution, and necessarily super

sedes the application of the death

statutes of the several States

281 US, at 44, 74 L ed at 691.

Thirty-four years have passed since

the Lindgren decision, and Congress

has let the Jones Act stand with

the interpretation this Court gave

it. The decision was a reasonable

one then. It provided the same

remedy for injury or death for all

seamen, the remedy that was and

is provided for railroad workers m

the Federal Employers’ Liability

Act.11 Whatever way be this Court s

special responsibility for fashioning

rules in maritime affairs,12 we do

not believe that we should now dis

turb the settled plan of rights and

liabilities established by the Jones

Act

*[379 US 156]

[6] ^Petitioner argues further

that even if the only available reme

dy for death is under the Jones Act,

the District Judge erred in refusing

to hold that the Jones Act provides

for damages for death for the bene

fit of the brother and sisters of

the decedent as well as for the

mother. Their right of recovery, if

any, depends on § 1 of the FELA,

45 USC § 51 (1958 ed.), which pro

vides that recovery of damages for

death shall be: “ for the benefit of

the surviving widow or husband and

children of such employee; and, if

none, then of such employee’s par

ents; and, if none, then of tne ne^t

of kin dependent upon such em

ployee . . .

205STATES STEEL COEP.

2d 199, 85 S Ct 308

In Chicago, B. & Q. R. Co. v Wells-

Dickey Trust Co. 275 US 161, 163,

72 L ed 216, 217, 48 S Ct 73, 59 ALR

758, this Court, speaking through

Mr. Justice Brandeis, held that this

provision creates “ three classes of

possible beneficiaries. But the lia

bility is in the alternative. It is to

one of the three; not to the several

classes collectively.” We are asked

to overrule this case so as to give a

right of recovery for the benefit of

all the members of all three classes

in every case of death. Both courts

below refused to do so, and we

agree. It is enough to say that we

adhere to the Wells-Dickey holding,

among other reasons because we

agree that this interpretation of the

Act is plainly correct. Cf. Poff v

Pennsylvania R. Co. 327 US 399, 90

L ed 749, 66 S Ct 603, 162 ALR 719.

[7,8] One other aspect of this

case remains to be mentioned. The

complaint sought to recover dam

ages for the estate because “ dece

dent suffered severe personaMnju-

ries which caused him excruciating

pain and mental anguish prior to

his death.” Petitioner contends

that the seaman’s claim for pain and

suffering survives his death and

can be brought on a theory of un

seaworthiness by force of the Ohio

survival statute. The District

Judge struck the reference to the

Ohio survival statute from the com

plaint, and the Court of Appeals

held that there was “no substantial

basis, in this case,” for a claim for

*[379 US 157]

pain and *suffering prior to death.

There is, of course, no doubt that

the Jones Act through §9 of the

FELA, 45 USC § 59 (1958 ed.).13

provides for survival after the death

of the seaman of “ [a]ny right of ac-

— ---------------- ------— -------------- - . . , TIgr 13 36 stat 291, 45 USC § 59 (1958 ed):11. 35 Stat 65, as amended, 4o CSC 13. 3b b ^ g.yen by thl8

§§ 51-60 (1958 ed). , , . r)£>rson suffering injury shall12. See Fitzgerald v United States Lines chapter to a_ person suner S rgJ *senta.

Co- 371 US 16. 20-21 10 L «d 2d 20.

72i, 83 S Ct 1646, and cases there cited. tive, ior i

U...—

. .

m m

1 |

’ ' \ . Ml

i . ! tr® ' * ' • y * if 4

•- •* • - ■ •• • ■- - n

t j i -w- rv-rr.7''--- *S . -1 j : . .-»V~frX

■i

i

: o.

.... - *4

■ s ;

f*V;■i rV-,~*KeW*

■ • ': .'• '. :• . ■■- ..'■ :■■- ■':■:■■' . . • ■

• -r-i* ■ ■ • ■ ‘ ■ *• ■ ■ • ■ ■ . ■ ■• ■ ■ •■■ ■ ■’ ■ •■■ ■

. . ; ' ' ;1 ' ■' . ■ ; ■ •' ; '. • ' • rj

••r.-s, ■■ apfs i -A

■■M

■ ■ ■ ;- 'V > ■ ■ ■

4- Mi •<>- “f* ' i-JfV - <~r~r-»M. lie ' 1 »*•+-> 'xU’f fr • ■*«&£& «>*«

.! !

i J

1 ! I

-s-"4

M

w?

' . ■ ■ ■ ' ■ . • ■- • • - ■ ’:

mmMmm i:ami itsamaasi

206 U . b . b u p l v i i i t i

e A T T p p n t ?T r - n r v 'n ’T ’ q . L/UlLe;AWx iViJi. UiuO 13 L ed 2 1

tion given by this chapter,” i. e., of

his claim based on a theory of negli

gence. And we may assume, as we

have in the past,14 that after death

of the injured person a state surviv

al statute can preserve the cause of

action for unseaworthiness,16 which

would not survive under the general

maritime law.18 In holding that pe

titioner had not stated a claim en

titling her to recovery for the

decedent’s pain and suffering the

Court of Appeals relied on The Cor

sair, 145 US 335, 348, 36 L ed 727,

731, 12 S Ct 949, a case brought in

a federal court to recover damages

under a Louisiana survival statute

for alleged pain and suffering prior

to death by drowning where there

was an interval of “ about ten min

utes” between the accident and

death. The Court held such dam

ages could not be recovered there,

saying: “ . . . there is no averment

from which we can gather that these

pains and sufferings were not sub

stantially contemporaneous with her

death and inseparable as matter of

law from it.”

*[379 US 158]

t ‘ Plainly this Court did not hold in

’ The Corsair that damages cannot

ever be recovered for physical and

mental pain suffered prior to death

by drowning. The case held merely

that the averments of the plain

tiff there did not justify awarding

such damages in an action under the

Louisiana survival statute. The

Court’s language certainly did not

preclude allowance of such damages

in all circumstances under other

laws, or even under the Louisiana

statute in a case where pain and

suffering were “ not substantially

contemporaneous with . . . death

and inseparable as matter of law

from it.” In this day of liberality

in allowing amendment of pleadings

to achieve the ends of justice,17 the

issue whether the decedent’s estate

could recover here for pain and suf

fering prior to death should not have

been decided finally by the Court of

Appeals on the basis of mere

pleading. Therefore the question

whether damages can be recovered

for pain and suffering prior to death

on the facts of this case will re

main open. In all other respects

the judgment of the Court of Ap

peals is

Affirmed.

SEPARATE OPINIONS

Mr. Justice Goldberg, dissenting

in part.

on the merits of the basic question

presented for decision.

I agree that this case is properly

here, but disagree with the Court

The precise point at issue in this'

case is whether a suit in a federal

or husband and children of such employee,

and, if none, then of such employee’s par

ents; and, if none, then of the next of

kin dependent upon such employee, but in

such cases there shall be only one recovery

for the same injury.”

14. “Presumably any claims, based on

unseaworthiness, for damages accrued

prior to the decedent’s death would sur

vive, at least if a pertinent state statute

is effective to bring about a survival of

the seaman’s right.” Kernan v American

Dredging Co. 355 US 426, 430, note 4, 2

L ed 2d 382, 387, 78 S Ct 394. See also

Curtis v A. Garcia y Cia. 241 F2d o0,

36-37 (CA3d Cir): Holland v Steag, Inc.

143 F Supp 203, 205-206 (DCD Mass).

15. Cf. Just v Chambers, 312 US 383, 85

L ed 903, 61 S Ct 687.

16. Cortes v Baltimore Insular Line, Inc.

287 US 367, 77 L ed 368, 53 S Ct 173.

17. See Fed Rules Civ Proc 15; Foinan

v Davis, 371 US 187, 9 L ed 2d 222, 83

S Ct 227; United States v Hougham, 364

US 310, 5 L ed 2d 8, 81 S Ct 13; cf. Conley

" Gibson, 355 US 41, 2 L ed 2d 80, <8 S

Ct 99.

C

R.

sW .1; . „• v . < -- «• t*. •- ...... U -V v-m -------------------------------------------- -- - ■- . — ->’. j v W ^ r - - V i --

GILLESPIE v UNITED

379 US 148, 13 L ed

in no way be affected by enactment

of tbe federal law. 59 Cong Rec

4482-4486.”

From this expression of congres

sional purpose, the Court m Th

Tungus concluded that a suit in

admiralty for death of a longshore

man resulting from unseaworthiness

of a vessel may be maintained

against the vessel’s owner where the

death occurs in the waters of

State which provides a statutory

remedy for wrongful death.

It seems to me to strain credulity

to impute to Congress the intent

to eliminate state death remedies for

unseaworthiness where the decedent

*[379 US 166]

is a seaman while 'refusing to do so

in cases involving nonseamen. Y

this is the result oi the Court s fo

lowing Lindgren,

STATES STEEL CORP. 211

2d 199, 85 S Ct 308

quiring the satisfaction of reason

able expectations. I should think

that by allowing a remedy where one

is needed, by eliminating differences

not based on reason, while still leav

ing the underlying scheme of duties

unchanged, this sense of security

will not be weakened but strength

ened. The policies behind stare de

cisis point toward ignoring Lind

gren, not following it.

Finally, even though the Lindgren

dictum has been in existence for 34

years, no policy of stare decisis mili

tates against overruling Lindgren.

In refusing to follow Lindgren we

would not create new duties or

standards of liability; we would

merely allow a new remedy. Ship

owners are currently required to

maintain a seaworthy ship; seamen

and longshoremen currently recover

for death on the high seas and in

jury suffered anywhere due to an

unseaworthy vessel. The action of

a shipowner in maintaining his ves

sel will not be affected by now al

lowing recovery for wrongful death

in territorial water caused by un

seaworthiness. It is thus difficul

to find much if any reliance that

would justify the continuation of a

legal anomaly which would deny a

humane and justifiable remeay.

Stare decisis does not mean blind

adherence to irrational doctrine.

The very point of stare decisis is to

produce a sense of security in the

working of the legal system oy re-

I cannot agree that Congress in

enacting the Jones Act, designed to

provide liberal recovery for injured

workers,” intended to create the

anomaly perpetuated by the Court s

decision. I would reverse and tree

the lower federal courts to grant

relief in these cases—-relief which

many of them have indicated is just

and proper “ in terms of general

principles,” Fall v Esso Standard

Oil Co., supra, at 417, and which

they gladly would accord but for the

unfortunate and unnecessary com

pulsion of Lindgren.

*[379 US 167]

♦Since petitioner claims that Ohio

law allows recovery for a wrongful

death caused by unseaworthmess,

nothing in either the majority or

minority opinion in The Tungus v

Skovgaard, supra, would preclude

recovery. Only the Lindgren dictum

stands in the way. I would reject

this dictum and reverse.

Mr. Justice Harlan, dissenting.

I think that due regard for the

“ finality” rule governing the appel

late jurisdiction of the courts o

appeals requires that the judgment

below be vacated and the case re

manded to the Court of Appeals with

instructions to dismiss the appea

because the decision of the District

Court was not a “ final” one, and

hence not reviewable by the Court

of Appeals at this stage of the liti

gation.

Petitioner sought to recover in

.■ •• • - . . . . .

- " f l ■

212 U. S. SUPREME COURT REPORTS 13 Led 2d

this action upon two theories: neg

ligence under the Jones Act and

unseaworthiness under the general

maritime law. The District Court

dismissed the unseaworthiness claim

in the complaint, and petitioner ap

pealed. Although petitioner seemed

to recognize that the order was not

appealable,1 the Court of Appeals,

overruling respondent’s motion to

dismiss for lack of jurisdiction, af

firmed on the merits and this Court

granted certiorari over respondent’s

showing that the Court of Appeals

should not have entertained the ap

peal. The Court substantially af

firms the judgment of the Court of

Appeals and the parties are re

manded to a trial on the merits, but

only after they have incurred need

less delay and expense in conse

quence of the loose practices sanc

tioned by the Court of Appeals and

in turn by this Court. This case

thus presents a striking example of

the vice inherent in a system which

*[379 US 168] _

*permits piecemeal litigation of the

issues in a lawsuit, a vice which

Congress in 28 USC § 1291 intended

to avoid by limiting appeals to the

courts of appeals2 only from “ final

decisions” of the district courts,

with exceptions not here relevant.3

1. After the appeal was filed, petitioner

unsuccessfully sought a writ of mandamus

to compel the District Court to certify its

order to the Court of Appeals under 28

USC § 1292(b), ante, pp. 202, 203.

2. The jurisdictional defect in this case

arises only from the lack of finality of

the District Court’s order. In United

States v General Motors Corp., 323 US 373,

89 L ed 311, 65 S Ct 357, 156 ALR 390;

Larson v Domestic & Foreign Commerce

Corp. 337 US 682, 93 L ed 1628, 69 S Ct

1457; and Land v Dollar, 330 US 731, 91

L ed 1209, 67 S Ct 1009, all cited in the

majority opinion, ante, pp. 203, 204, the

District Court had entered a final judg

ment, but the Court of Appeals reversed

and remanded the case for further proceed

ings. Thus the finality question before this

Court was simply whether it should re

view a nonfinal order of the Court of

Manifestly the decision of the Dis

trict Court reviewed by the Court

of Appeals lacked the essential qual

ity of finality; it involved but in

terstitial rulings in an action not

yet tried. The justifications given

by the Court for tolerating the lower

court’s departure from the require

ments of § 1291 are, with all respect,

unsatisfactory.

[9 ] 1. The Court relies on the dis

cretionary right of a district court

to certify an interlocutory order to

the court of appeals under § 1292 (b)

when the “ order involves a control

ling question of law',” but the Dis

trict Court in its discretion—and

rightly it turns out—did not make

such a certification in this case,4 *

*[379 US 169]

and the Court of Appeals, *equally

correctly in my judgment, refused

to order it to do so. The fact that

Congress has provided some flexi

bility in the final judgment rule

hardly lends support to the Court’s

attempt to obviate jurisdictional re

strictions whenever a court of ap

peals erroneously entertains a non

appealable order and hardship may

result if the substantive questions

are not then decided here.6

[TO] 2. Cohen v Beneficial Indus-

Appeals, which of course the Court clearly

has authority to do under 28 USC § 1254

(1) (1958 ed.).

3. See 28 USC § 1292 (1958 ed).

[9 ] 4. The purpose of § 1292(b) was to

permit a district judge, in his discretion,

to obtain immediate review of an order

which might control the further conduct

of the case and which normally involves

an unsettled question of law. Cf. 28 USC

§ 1254(3) (1958 ed.). In this case the

District Court's ruling was controlled by

Lindgren v United States, 281 US 38, 74

L ed 686, 50 S Ct 207, and the validity of

that ruling could only be tested by having

certiorari issue from this Court. In that

posture, I think the District Court was

quite right in not wanting to delay the

litigation on the chance that this Court

would re-evaluate its decision in-Lindgren.

5. Compare Sehlagenhauf v Holder, 379

• ■ • • • • a ■

' i • ':

A vy &J&**

Vi :■■;.■ i ' " • ■ •-■ ■; i-i ’ ■ , - ; ■ ■■

■

f

]

i

GILLESPIE v UNITED STATES STEEL COSP. 213

379 US 148, 13 L ed 2d 199, 85 S Ct 308

trial Loan Corp. 337 US 541, S3 that1 “ it seems clear now that the

L ed 1528, 69 S Ct 1221, does not case is before us that the eventual

support a different result. As the costs, as all the parties recognize,

Court in that case stated, § 1291 will certainly be less if we now pass

on the questions presented here

rather than send the case back with

does not permit appeals from de

cisions “where they are but steps

towards final judgment in which

they will merge . . . [and are

not] claims of right separable from,

and collateral to, rights asserted in

the action, too important to be

denied review and too independent

of the cause itself to require that

appellate consideration be deferred

until the whole case is adjudicated.”

337 US, at 546, 93 L ed at 1536.

It is clear in this case that had

petitioner proceeded to trial and won

on her Jones Act claim, her asserted

cause of action for unseaworthiness

would have merged in the judgment.

See, Baltimore S.S. Co. v Phillips,

274 US 316, 71 L ed 1069, 47 S Ct

600. Conversely, her claim would

have been preserved for appeal had

she lost on her Jones Act claim.

Surely the assertion that petitioner

is entitled to submit her unseaworth

iness theory to the jury is not col

lateral to rights asserted in her ac

tion, so as to entitle her to an

appeal before trial.

*[379 US 170]

*3. Finally, the Court’s suggestion

those issues undecided,” ante, p. 203,

furnishes no excuse for avoidance

of the finality rule. Essentially such

a position would justify review here

of any case decided by a court of

appeals whenever this Court, as it

did in this instance, erroneously

grants certiorari and permits coun

sel to brief and argue the case on

the merits. That, I believe, is nei

ther good law nor sound judicial

administration.* 6

I would vacate the judgment of

the Court of Appeals and remand the

case to that court with directions to

dismiss petitioner’s appeal for lack

of jurisdiction.

Memorandum of Mr. Justice

Stewart.

While I agree with Mr. Justice

Harlan that this case is not properly

here, the Court holds otherwise and

decides the issues presented on their

merits. As to those issues, I join

the opinion of the Court.

US 104, at 110, 13 L ed 2d 152, at 159, 85 S

Ct 234. The presence of the brother and

sisters, ante, p. 203 of the Court’s opinion,

cannot somehow serve to make the Dis

trict Court order final. They were parties

only to the mandamus proceeding, Court’s

opinion ante, pp. 202, 203, n. 7, their claims

were not severable from petitioner’s,

id., p. 203, and the merit of their claims

likewise depended on a holding that Lind-

gren was overruled, see n. 4, supra. I can

see no “ injustice” resulting tG the brother

and sisters by delaying review of the

order until after final judgment which is

not also present with respect to petitioner.

6. Understandably counsel for the re

spondent, as he explained in oral argu

ment, did not brief the finality point fol

lowing the grant of certiorari; he assumed

that the granting of the petition, despite

his having raised the matter in his re

sponse thereto, indicated that the Court

had no interest in the question.

I h

■ !

t | «

. . *

I

EDITOR’S NOTE

An annotation on “ Recovery, in action under Federal Employers’ Liability Act or

Jones Act for death of employee, of damages for deceased’s pain and suffering between

injury and death— federal eases" appears p. 1013, infra.

' ' • ' ' .

. . . . . . . . . ■ ■ ' . . . . . . . .. • ; •

» _ • • • . ■ : - •