Stovall v. City of Cocoa, Florida Brief of Appellants

Public Court Documents

December 3, 1996

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Stovall v. City of Cocoa, Florida Brief of Appellants, 1996. 63a2af41-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d37c29b1-9b89-4117-84e2-6f69055cafb4/stovall-v-city-of-cocoa-florida-brief-of-appellants. Accessed January 29, 2026.

Copied!

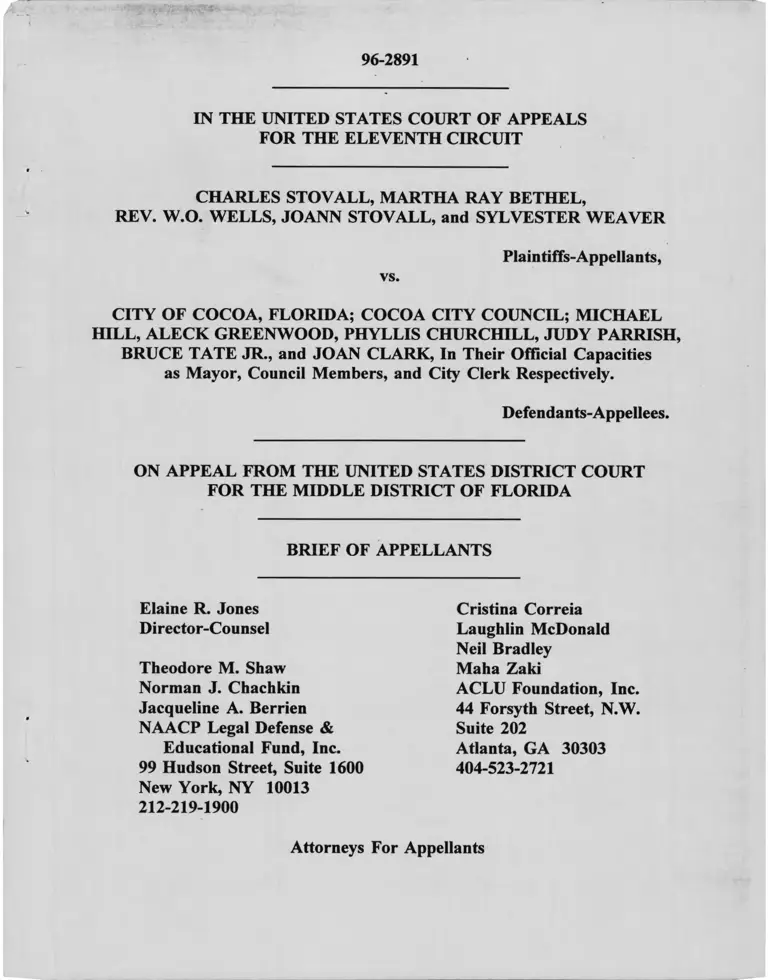

96-2891

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

CHARLES STOVALL, MARTHA RAY BETHEL,

REV. W.O. WELLS, JOANN STOVALL, and SYLVESTER WEAVER

vs.

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

CITY OF COCOA, FLORIDA; COCOA CITY COUNCIL; MICHAEL

HILL, ALECK GREENWOOD, PHYLLIS CHURCHILL, JUDY PARRISH,

BRUCE TATE JR., and JOAN CLARK, In Their Official Capacities

as Mayor, Council Members, and City Clerk Respectively.

Defendants-Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF FLORIDA

BRIEF OF APPELLANTS

Elaine R. Jones

Director-Counsel

Theodore M. Shaw

Norman J. Chachkin

Jacqueline A. Berrien

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, Suite 1600

New York, NY 10013

212-219-1900

Cristina Correia

Laughlin McDonald

Neil Bradley

Maha Zaki

ACLU Foundation, Inc.

44 Forsyth Street, N.W.

Suite 202

Atlanta, GA 30303

404-523-2721

Attorneys For Appellants

No. 96-2891, STOVALL, et al.. v. CITY OF COCOA, et al.

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS

AND CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

Pursuant to Eleventh Circuit Rule 26.1, the following is an alphabetical list

of the trial judge, attorneys, persons, firms, partnerships and corporations with any

known interest in the outcome of this appeal:

1. Amari, Theriac, Eisenmenger & Woodman, P.A.,

Counsel for Defendants/Appellees

2. American Civil Liberties Union Foundation, Inc.,

Co-Counsel for Plaintiffs/Appellants

3. Jacqueline Berrien, Co-Counsel for Plaintiffs/Appellants

4. Martha Ray Bethel, Plaintiff/Appellant

5. Neil Bradley, Co-Counsel for Plaintiffs/Appellants

6. Norman J. Chachkin, Co-Counsel for Plaintiffs/Appellants

7. Phyllis Andrea Churchill, Defendant/Appellee

8. Cianfrogna, Telfer, Reda and Faherty, P.A., Counsel for Fred Galey

9. Joan Clark, Defendant/Appellee

10. City of Cocoa, Defendant/Appellee

11. Cocoa City Council, Defendant/Appellee

C -l o f 3

No. 96-2891, STOVALL, et al.. v. CITY OF COCOA, et al.

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS

AND CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

12. Cristina Correia, Co-Counsel for Plaintiffs/Appellants

13. Fred Galey, Brevard County Supervisor of Elections, Interested Party

14. Aleck James Greenwood, Defendant/Appellee

15. Frank J. Griffith, Counsel for Fred Galey

16. Michael Ashley Hill, Defendant/Appellee

17. J. Wesley Howze, Jr., Counsel for Defendants/Appellees

18. Elaine R. Jones, Co-Counsel for Plaintiffs/Appellants

19. Laughlin McDonald, Co-Counsel for Plaintiffs/Appellants

20. NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc.,

Co-Counsel for Plaintiffs/Appellants

21. Judy Jackson Parrish, Defendant/Appellee

22. Hon. G. Kendall Sharp, District Court Judge

23. Theodore Shaw, Co-Counsel for Plaintiffs/Appellants

24. Charles L. Stovall, Plaintiff/Appellant

25. Joan Stovall, Plaintiff/Appellant

C-2 o f 3

No. 96-2891, STOVALL, et al., v. CITY OF COCOA, et al.

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS

AND CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

26. Bruce Winfred Tate, Jr., Defendant/Appellee

27. Sylvester Weaver, Plaintiff/Appellant

28. Rev. W. O. Wells, Plaintiff/Appellant

29. Maha Zaki, Co-Counsel for Plaintiffs/Appellants

Cccuvuc

Cristina Correia

C-3 o f 3

STATEMENT REGARDING ORAL ARGUMENT

This case presents important issues concerning the approval and enforcement

of settlement agreements by the federal district courts and the application of Miller

v. Johnson, 515 U.S. ___, 115 S. Ct. 2475 (1995) to settlement agreements in

litigation under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1973. Due to the

importance of the issues presented, oral argument may assist the Court in the

resolution of this appeal.

CERTIFICATE OF TYPE SIZE AND STYLE

The type size used in this brief is 14 point. The type style is Times New

Roman.

l

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS AND

CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT ...................................... C-l

STATEMENT REGARDING ORAL ARGUMENT .................................... .. . i

CERTIFICATE OF TYPE SIZE AND STYLE.................................................. i

TABLE OF CONTENTS.................................................................................... ii

TABLE OF CITATIONS .................................................................................. v

STATEMENT OF SUBJECT MATTER JURISDICTION ............................. x

STATEMENT OF APPELLATE JURISDICTION ......................................... x

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES ...................................................................... 1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE.......................................................................... 2

Nature of the C ase .................................................................................... 2

Course of Proceedings and Dispositions in the Court B elow ................. 2

Statement of F a c ts .................................................................................... 3

Statement of the Standard of Review ..................................................... 5

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT................................................................. 6

ARGUMENT ..................................................................................................... 8

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. The District Court Erred In Permitting The City Of Cocoa Unilaterally

To Withdraw The Jointly Submitted Consent Decree............................. 8

A. The Parties’ Executed Settlement Agreement Is B inding............ 10

B. The Parties Executed A Valid Settlement Agreem ent.....................14

C. State Law Is Not A Bar To Entry Of The Consent

Decree................................................................................................16

D. Equity Requires That The Consent Decree Be Enforced ................20

II. The Consent Decree Is Constitutional.......................................................21

A. The Record Clearly Demonstrates That Race Was Not

The Predominant Factor In The Creation Of The 4-1

District P la n ......................................................................................26

B. The Plan Embodied In The Proposed Consent Decree

Satisfies Strict Scrutiny ...................................................................30

1. The Consent Decree Is Justified By A

Compelling Government Interest...........................................31

2. The Consent Decree Is Narrowly T ailored...................... 33

CONCLUSION .................................................................................................... 35

Page

in

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ADDENDUM

Map of 4-1 District P la n ................................................Addendum page 1

Sec. 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965,

42 U.S.C. § 1973 ................................................Addendum page 2

Fla. Stat. § 166.031 .......................................................Addendum page 3

Cocoa City Charter, Art. Ill, § 13(b) .......................... Addendum page 4

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

Page

IV

TABLE OF CITATIONS

Alien v. Alabama State Bd. Of Educ., 816 F.2d 575 (11th Cir. 1987) . 6, 10, 11

Armstrong v. Adams, 869 F.2d 410 (8th Cir. 1988) ......................................... 19

Bonner v. Prichard, 661 F.2d 1206 (11th Cir. 1981) {en banc) ................. 7

Brewer v. Muscle Shoals Bd. O f Educ., 790 F.2d 1515 (11th Cir. 1986) . . . . 11

Bush v. Vera,___U .S.___ , 116 S. Ct. 1941 (1996) ..................................passim

Carson v. American Brands, Inc., 450 U.S. 79 (1981) ............................... xi, 9

Cia Anon Venezolana De Navegacion v. Harris, 374 F.2d 33 (5th Cir. 1967) 15

Crosby Forrest Products, Inc. v. Byers, 623 So.2d 565

(Fla. 5th Dist. Ct. App. 1993) ................................................................. 14

Daly v. School District o f Darby Township, 434 Pa. 286,

252 A.2d 638 (1969) ............................................................................... 15

DeWitt v. Wilson,___U .S .___ , 115 S. Ct. 2637 (1995) ........................ 24, 31

Dillard v. Crenshaw County, 748 F. Supp. 819 (M.D. Ala. 1990) 7, 10, 12, 19

Dorson v. Dorson, 393 So.2d 632 (Fla. 4th Dist. Ct. App. 1981)................. 13

Eatmon v. Bristol Steel & Iron Works, Inc., 769 F.2d 1503 (1985)............. 11

Floyd v. Eastern Airlines, Inc., 872 F.2d 1462 (11th Cir. 1989)

rev’d sub nom. on other grounds, Eastern Airlines, Inc. v. Floyd,

Cases Pages

v

TABLE OF CITATIONS

499 U.S. 530 (1991)............................................................................. 6, 14

Fulgence v. J. Ray McDermott & Co., 662 F.2d 1207 (5th Cir. 1981) .......... 6

George v. City o f Cocoa, 78 F.3d 494 (11th Cir. 1996) ......................x, 1, 2, 4

Gooding v. Wilson, 405 U.S. 518 (1972) .......................................................... 6

Gunn Plumbing. Inc. v. Dania Bank, 252 So.2d 1 (Fla. 1971)........................ 13

In re Birmingham Reverse Discrimination Emp. Lit,

20 F.3d 1525 (11th Cir. 1994)................................................................ 5

In re Smith, 926 F.2d 1027 (11th Cir. 1991).....................................................10

In re U.S. Oil and Gas Litigation, 967 F.2d 489 (11th Cir. 1992) ................. 10

Jeffers v. Clinton, 730 F. Supp. 196 (E.D. Ark 1990) (three judge court)

aff’d mem., 498 U.S. 1019 (1991) ..........................................................27

Johnson v. DeGrandy,___U.S. ___ , 114 S. Ct. 2647 (1 9 9 4 )................. 22, 32

Johnson v. Miller, 864 F. Supp. 1354 (S.D. Ga. 1994)

aff’d 515 U .S.___, 115 S. Ct. 2475 (1995)............................................ 31

Lotspeich Co. v. Neogard Corp., 416 So.2d 1163

(Fla. 3rd Dist. Ct. App. 1982) ................................................................. 13

Major v. Treen, 574 F. Supp. 325 (E.D. La. 1983) (three judge co u rt) ..........27

Cases Pages

vi

TABLE OF CITATIONS

Maseda v. Honda Motor Co., 861 F.2d 1248 (11th Cir. 1988)................... 6, 14

McDaniel v. Sanchez, 452 U.S. 130 (1981) ..................................................... 19

Miller v. Johnson, 515 U.S. __ , 115 S. Ct. 2475 (1995)........................ passim

Murchison v. Grand Cypress Hotel Corp., 13 F.3d 1483 (11th Cir. 1994) . . . 9

Newell v. Prudential Ins. Co. o f America,

904 F.2d 644 (11th Cir. 1990)................................................................. 5

Pettinelli v. Danzig, 722 F.2d 706 (11th Cir. 1984)......................................... 14

Potter v. Washington County, Fla., 653 F. Supp. 121 (N.D. Fla. 1986).......... 19

Reed By And Through Reed v. U.S., 717 F. Supp. 1511 (S.D. Fla. 1988),

a ffd 891 F.2d 878 (1 1th Cir. 1990) ........................................... 7, 12, 21

Reed By And Through Reed v. U.S., 891 F.2d 878 (11th Cir. 1990) . . 7, 11, 12

Rhein Medical, Inc. v. Koehler, 889 F. Supp. 1511 (M.D. Fla. 1995) . 7, 10, 12

Robbie v. City o f Miami, 469 So.2d 1384 (Fla. 1985) .................................... 13

Rufo v. Inmates o f Suffolk County Jail, 502 U.S. 367 (1992)................... 22, 25

Schwartz v. Florida Bd. Of Regents, 807 F.2d 901 (11th Cir. 1987).............. 11

Shapiro v. Associated Intern. Ins. Co.,

899 F.2d 1116 (11th Cir. 1990) ....................................................... 6, 14

Cases Pages

vii

TABLE OF CITATIONS

Cases Pages

Shaw v. Hunt, ___U .S.___ , 116 S. Ct. 1894 (1996)....................................... 24

Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S. 630, 113 S. Ct. 2816 (1993)............ 22, 24, 26, 27, 30

Straw v. Barbour County, 864 F. Supp. 1148 (M.D. Ala. 1994)...................... 19

Tallahassee Branch ofNAACP v. Leon County, Fla., 827 F.2d 1436

(11th Cir. 1987), cert, denied, 488 U.S. 960 (1988) ............................. 19

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 36 (1986) ................................................passim

Thomas v. State o f La., 534 F.2d 613 (5th Cir. 1976) ................. 7, 10, 12, 13

United States v. City o f Miami, Fla., 664 F.2d 435 (1981) (en banc) ............17

U.S. E.E.O.C. v. Tire Kingdom, 80 F.3d 499 (11th Cir. 1996)........................ 5

Utilities Comm ’n Of New Smyrna Beach v. Fla. PSC,

469 So.2d 731 (Fla. 1985)........................................................................ 13

Voinovich v. Quilter, 507 U.S. 146, 113 S. Ct. 1149 (1993) ............ 22, 27, 31

Wallace v. Townsell, 471 So.2d 662 (Fla. 5th Dist. Ct. App. 1985) .............. 14

Wilson v. Eu, 4 Cal. Rptr. 2d 379 (1992).......................................................... 25

Wise v. Lipscomb, 437 U.S. 535 (1978)............................................................ 18

Wong v. Bailey, 752 F.2d 619 (11th Cir. 1985)................................................ 11

vm

TABLE OF CITATIONS

Statutes and City Charter Page

Sec. 2 of the Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1973 ..................................passim

28 U.S.C. § 1 2 9 1 .............................................................................................xi

28 U.S.C. § 1292(a)(1) ................................................................................. .. . xi

28 U.S.C. § 1331 x

28 U.S.C. § 1343(a)(3) ...................................................................................... x

28 U.S.C. § 1343(a)(4) ...................................................................................... x

28 U.S.C. § 2201 ................................................................................................ x

42 U.S.C. §1983 ................................................................................................ x

Fla. Stat. §166.031(2)......................................................................................... 16

Fla. Stat. §166.031(3) 17

Fla. Stat. §166.031(5).................................................................................. 16, 17

Cocoa City Charter, Ait. Ill, § 13(b) .................................................................18

IX

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION

Statement of Subject Matter Jurisdiction

This is an action arising under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C.

§ 1973. Subject matter jurisdiction in the district court was invoked pursuant to 28

U.S.C. §§ 1331, 1343(a)(3), 1343(a)(4) and 2201, and authorized by 42 U.S.C.

§1983.

Statement of Appellate Jurisdiction

On May 20, 1996, on remand from this Court,1 the district court entered an

Endorsed Order granting Defendants’ Motion To Withdraw Joint Motion To Enter

Consent Decree And Judgment. R2-52 [Order]2. The district court’s Order has

1 This Court reversed an earlier Order which had voided a Consent Decree and

refused to enter judgment. George v. City o f Cocoa, 78 F.3d 494 (1996). (Mary

George was granted leave to withdraw as a plaintiff on March 14, 1995, and she

was granted leave to withdraw as an appellant in this Court on March 29, 1995.)

2 The district court docket sheet does not provide a document number for the

court’s Endorsed Order of May 20, 1996 which granted defendants’ motion. The

motion was docketed as R2-52. References in this brief to the Endorsed Order will

appear as "R2-52 [Order]". The "Endorsed Order" is the front page of the motion

with a handwritten notation that the motion is "granted" and "case shall proceed to

x

the practical effect of denying plaintiffs the injunctive relief provided in the parties’

Consent Decree. Rl-293. Plaintiffs timely filed a notice of appeal on June 19,

1996. R2-58. Jurisdiction in this Court is proper pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §§ 1291

and 1292(a)(1). Carson v. American Brands, Inc., 450 U.S. 79 (1981).

This Court raised the issue of jurisdiction sua sponte. Appellants have filed

a brief arguing that jurisdiction is proper pursuant to both 28 U.S.C. §§1291 and

1292(a)(1). See Appellants’ Response To The Court’s Inquiry Regarding

Jurisdiction, filed on July 16, 1996.

trial".

3 The proposed Consent Decree was submitted with the Joint Motion To Enter

Consent Decree And Judgment on July 29, 1994. These documents have been

docketed under a single entry, no. 29. References in this brief to the Consent

Decree will appear as "Rl-29-page [decree]".

xi

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES

1. Whether, following this Court’s reversal of the district court’s 1994 Order

refusing to enter the parties’ proposed consent decree and its remand "for further

proceedings not inconsistent with" the opinion in George v. City o f Cocoa, 78 F.3d

494, 499 (11th Cir. 1996), the district court violated this Court’s mandate, and

erred, as a matter of law, when it failed to enforce the parties’ settlement and

permitted defendants unilaterally to withdraw the parties’ Joint Motion To Enter

Consent Decree And Judgment?

1

STATEM ENT OF THE CASE

Nature of the Case

Plaintiffs, African-American citizens and registered voters in the City of

Cocoa, filed this action under Sec. 2 of the Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1973,

alleging that the at-large/numbered post method of electing the Cocoa City Council

dilutes the voting strength of African-American voters. Rl-1-13.

Course of Proceedings and Disposition in the Court Below

This is an appeal from an Order granting defendants’ Motion To Withdraw

Joint Motion To Enter Consent Decree And Judgment. R2-52 [Order]. On July

28, 1994 the parties had filed a Joint Motion To Enter Consent Decree & Judgment

along with a proposed Consent Decree with the district court (herewith "Joint

Motion"). Rl-29. In late 1994 the district court entered an Order voiding the

parties’ proposed consent decree. R2-40. This Court reversed the district court’s

order and remanded the case "for further proceedings not inconsistent with this

[Court’s] opinion." George v. City o f Cocoa, 78 F.3d 494, 499 (11th Cir. 1996).

Three days after this Court’s mandate issued, defendants filed a Motion To

Withdraw Joint Motion To Enter Consent Decree And Judgment. R2-52. Plaintiffs

filed a brief in opposition. R2-57. Without benefit of a hearing, and with no

explanation of the basis for its ruling, the district court entered an Endorsed Order

2

granting defendants’ motion and directing that the case proceed to trial. R2-52

[Order].4 This appeal followed.

Statement of the Facts

The City of Cocoa has a total population of 17,722. African-Americans

constitute 28% of the city’s population. Rl-1-5 and Rl-13-2. Despite this

substantial minority population, at the time this suit was brought only two African-

Americans had ever been elected to the five (5) member city council and none had

been elected since 1981. R2-36-2.

While discovery was underway the parties entered into settlement

negotiations and ultimately agreed upon an electoral system for the election of the

Cocoa City Council whereby four members of the council are to be elected from

single-member districts and one member, who also serves as mayor, continues to

be elected at-large. R1-29-2, 3 [decree]. On May 10, 1994, by a 3 to 2 vote, the

Council approved the election plan incorporated in the parties’ proposed consent

decree. Rl-29-3 [decree]. The parties then filed a Joint Motion To Enter Consent

Decree And Judgment. Rl-29. Four voters appeared as amici and filed objections

4 Since the court did not write an opinion explaining the basis for its ruling,

this brief will address all of the arguments advanced by defendants’ motion and

memorandum in support thereof.

3

to the parties’ proposed decree. Rl-325. After briefing and a hearing, the district

court issued an opinion holding that under Florida law, the sole African-American

on the city council should have abstained from voting on the remedy plan because

"as an African-American candidate he stood to gain inordinately from the vote" and

voiding the Consent Decree. R2-40-6, 8. This Court reversed the district court’s

Order and remanded the case to the district court "for further proceedings not

inconsistent with this [Court’s] opinion." George v. City o f Cocoa, 78 F.3d at

499.6

Three days after this Court’s mandate issued, defendants filed their Motion

To Withdraw Joint Motion To Enter Consent Decree & Judgment, which was

subsequently granted. R2-52 and R2-52 [Order]. As a result, more than two years

after the parties entered into a settlement agreement, elections continue to be held

5 Amici Joel Robinson, et al., participated in the proceedings below for the

limited purpose of presenting objections to the parties’ Consent Decree. Amici

advised the district court that they did "not seek to intervene in the underlying

action . . . " and sought "only to be heard in opposition to entry of a proposed

consent decree in this case." Rl-30-1 n. 1.

6 Amici chose not to participate in the appeal. See Amici’s Notice To Court,

George v. City o f Cocoa, 11th Cir. No. 94-3453, dated April 3, 1995.

4

under the at-large system which was to be replaced by the new electoral plan

embodied in the settlement. R3-61, R3-61 [Order]7, and R3-63.

On June 29, 1996 Plaintiffs filed a Motion To Enforce Mandate, Or In The

Alternative, Petition For Writ Of Mandamus with this Court, which was denied on

July 10, 1996.8

Statement of the Standard of Review

This appeal presents issues concerning the district court’s determination of

questions of law.9 Review of a district court’s rulings of law is de novo. U.S.

E.E.O.C. v. Tire Kingdom, 80 F.3d 449, 450 (11th Cir. 1996); In re Birmingham

Reverse Discrimination Emp. Lit, 20 F.3d 1525, 1540 (11th Cir. 1994); Newell v.

Prudential Ins. Co. o f America, 904 F.2d 644, 649 (11th Cir. 1990).

7 The district court docket sheet does not provide a document number for the

court’s Endorsed Order of Sept. 11, 1996 denying Plaintiffs’ Motion For Injunction

Pending Appeal (R3-61). References in this brief to this Endorsed Order will

appear as "R3-61 [Order]".

8 The motion to enforce the mandate was denied as to appeal No. 94-3453.

The petition for writ of mandamus was denied as to No. 96-2919.

9 The district court made no findings of fact and the parties do not dispute the

existence of an agreement, only its enforceability. See R2-52-Exhibit A.

5

To the extent that this appeal involves interpretations of state law, this Court

is "‘bound by a decision of a Florida District Court of Appeal on questions of

Florida state law, absent a strong showing that the Florida Supreme Court would

decide the issue differently.’" Shapiro v. Associated Intern. Ins. Co., 899 F.2d

1116, 1123 (11th Cir. 1990) (quoting Maseda v. Honda Motor Co., 861 F.2d 1248,

1257 n.14 (11th Cir. 1988)); Floyd v. Eastern Airlines, Inc., 872 F.2d 1462, 1466-

1467 (11th Cir. 1989) (reversing district court’s interpretation of state law) rev ’d

sub nom. on other grounds, Eastern Airlines, Inc. v. Floyd, 499 U.S. 530 (1991).

See also, Gooding v. Wilson, 405 U.S. 518, 525 n. 3 (1972) (holding that federal

courts follow state appellate court decisions as to state law).

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT

The district court erred in granting defendants’ Motion To Withdraw Joint

Motion To Enter Consent Decree & Judgment. The parties have entered into a

lawful settlement agreement and defendants have failed to provide any legal

justification for their failure to adhere to this agreement.

Settlement agreements are binding. Allen v. Alabama State Bd. OfEduc.,

816 F.2d 575 (11th Cir. 1987); Fulgence v. J. Ray McDermott & Co., 662 F.2d

6

1207 (5th Cir. 1981); Thomas v. State o f La., 534 F.2d 613 (5th Cir. 1976)10;

Rhein Medical, Inc. v. Koehler, 889 F. Supp. 1511 (M.D. Fla. 1995); Dillard v.

Crenshaw County, 748 F. Supp. 819 (M.D. Ala. 1990); Reed By And Through Reed

v. U.S., 111 F.Supp. 1511 (S.D. Fla. 1988), aff’d 891 F.2d 878 (11th Cir. 1990).

The proposed consent decree is constitutional, and the district court has

already concluded as much. R2-43-3. The express puiposes of the Consent Decree

included 1) "provid[ing] minority voters equal access to the political processes" and

"enhancing] the political participation and awareness of all citizens." R1-29-2

[Decree] (emphasis added). As defendants themselves have represented, the 4-1

District Plan incorporated in the Consent Decree adheres to traditional redistricting

principles. R2-36-15, R2-35-Appendix C, Addendum Page 1. "[SJtrict scrutiny

only applies where ‘the State has relied on race in substantial disregard of

customary and traditional districting practices.’" Bush v. Vera, 116 S. Ct. 1941,

1951 (1996) (O’Connor, J., concurring) (quoting Miller v. Johnson, 115 S. Ct. at

2497). Therefore, the 4-1 District Plan is not subject to strict scrutiny review.

Even if the Consent Decree were subject to strict scrutiny review, it would

10 Decisions of the former Fifth Circuit rendered prior to October 1, 1981 are

binding precedent in the Eleventh Circuit. Bonner v. City o f Prichard, 661 F.2d

1206 (11th Cir. 1981) (en banc).

7

easily satisfy such heightened scrutiny. Strict scrutiny would require the districting

plan to be justified by a compelling government interest and narrowly tailored to

meet that interest. Miller, at 2482. Compliance with Sec. 2 of the Voting Rights

Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1973, is a compelling government interest. Bush v. Vera, 116 S.

Ct. at 1968 (O’Connor, J., concurring). Prior to entering in the Consent Decree the

City of Cocoa investigated the allegations and claims in the complaint and had a

strong basis in belief that the present at-large numbered post election system

violates Sec. 2 of the Voting Rights, 42 U.S.C. § 1973. R2-36-3-5. The Consent

Decree is narrowly tailored. The 4-1 District Plan only has one majority-minority

district and retains one at-large seat. R1-29-2-3 [decree]. The majority African-

American district is both compact and contiguous. R2-36-15-16. The Consent

Decree provided a staggered implementation schedule, permitting incumbent city

council members to serve out their full tenns. Rl-29-4-5 [decree].

There being no credible argument that the Consent Decree is unlawful, the

district court’s Order, permitting defendants to escape the binding effect of the

settlement, should be reversed and the case remanded to the district court with

instructions that that court enter the Consent Decree.

8

ARGUMENT

I. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN PERMITTING THE CITY OF

COCOA UNILATERALLY TO WITHDRAW THE JOINTLY

SUBMITTED CONSENT DECREE.

There is no question that the Cocoa City Council approved the settlement

embodied in the proposed Consent Decree. Indeed, defendants’ motion in the

district court was styled "Motion To Withdraw Joint Motion To Enter Consent

Decree And Judgement". R2-52 (emphasis added). Defendants concede that they

approved the consent decree, agreed to its terms, and authorized their attorney to

seek court approval of the decree. See, R2-52-Exhibit A ("Whereas, on July 26,

1994, the City Council of the City of Cocoa, Florida, approved a 4-1 District Map

and Consent Decree and authorized the City Attorney to submit the same to the

Court for the Court’s action"); R2-53-1 ("A review of the proposed Consent

Decree discloses the Co-Defendant City had agreed to change its at large system

of voting in elections to a system which divided the commission races into four

distinct districts, . . . ").

Consent decrees are the preferred means of resolving litigation. Carson v.

American Brands, Inc., 450 U.S. 79, 86-88 (1981); Murchison v. Grand Cypress

Hotel Corp., 13 F.3d 1483, 1487 (11th Cir. 1994) ("We favor and encourage

9

settlements in order to conserve judicial resources."); In re U.S. Oil and Gas

Litigation, 967 F.2d 489, 493 (11th Cir. 1992); In Re Smith, 926 F.2d 1027, 1029

(11th Cir. 1991) ("Settlement is generally favored because it conserves scarce

judicial resources."); Rhein Medical, Inc. v. Koehler, 889 F. Supp. 1511, 1516

(M.D. Fla. 1995) ("Settlements are highly favored and will be enforced whenever

possible."); Thomas v. State o f La., 534 F.2d 613, 615 (5th Cir. 1976) ("Settlement

agreements have always been a favored means of resolving disputes.") "The

importance of settlements in the resolution of . . . voting rights cases in particular

cannot be overstated." Dillard v. Crenshaw County, 748 F. Supp. 819, 823 (M.D.

Ala. 1990). The district court erred in permitting defendants unilaterally to

withdraw from the settlement into which they had entered.

A. The Parties’ Executed Settlement Agreement Is Binding.

As addressed above, the City of Cocoa does not contend that a settlement

was not reached by the parties. Instead, in the court below, defendants merely

asserted, without authority, that since the Consent Decree "has not been executed

by the [district] Court, Co-Defendants are free to withdraw their consent. . ." R2-

53-3. In fact, the decisional law is to the contrary; a government defendant is

bound to a settlement agreement which it approves. Allen v. Alabama State Bd. Of

10

Educ., 816 F.2d 575, 577 (11th Cir. 1987)11 ("The fact that the board later

11 There is some division in this Circuit on whether state or federal law

governs the enforcement of a settlement agreement where the rights at issue are

derived from federal law. See Schwartz v. Florida Bd. Of Regents, 807 F.2d 901,

905 (11th Cir. 1987) (applying Florida’s general contract law to settlement in Title

VII action and citing as authority, Wong v. Bailey, 752 F.2d 619, 621 (11th Cir.

1985), which was a diversity action enforcing settlement in action arising under

state law); Eatmon v. Bristol Steel & Iron Works, Inc., 769 F.2d 1503, 1516 (1985)

(applying federal law in enforcement of conciliation agreement in Title VII action);

Allen v. Alabama State Bd. Of Educ., 816 F.2d 575, 577 ("the validity of the

settlement is a matter of federal law," but "it is important that. . . the parties have

presented no rule of [state] law . . . requiring particular formalities to be observed

by the [defendants] before their decisions become final and effective"); Brewer v.

Muscle Shoals Bd. O f Educ., 790 F.2d 1515, 1519 (11th Cir. 1986) (applying

federal law in enforcement of predetermination settlement agreement in Title VII

action); Reed By And Through Reed v. U.S., 891 F.2d 878, 881 (11th Cir. 1990)

(applying state law to enforcement of settlement in action under Federal Tort

Claims Act). In the case sub judice, there is no question that defendants are bound

to this settlement, under application of either federal or state law.

11

changed its mind after unfavorable publicity does not change the fact that it had

already approved the settlement . . . "). The settlement agreement in Allen was

enforced even though "no one signed the agreement on the Board’s behalf, and no

formal vote had been taken by the Board." 816 F.2d at 576. See also, Rhein

Medical, Inc. V. Koehler, 889 F. Supp. 1511, 1516 (M.D. Fla. 1995) ("Federal

district courts have inherent power to summarily enforce settlement agreements

entered into by party litigants in a pending case"); Dillard v. Crenshaw County, 748

F. Supp. 819, 828-831 (M.D. Ala. 1990) (refusing to allow the Shelby County

Commission to withdraw its consent to the proposed settlement of a voting rights

lawsuit, and entering a Consent Decree despite defendants’ belatedly asserted

objections); Reed By And Through Reed v. U.S., 717 F. Supp. 1511, 1516 (S.D.

Fla. 1988) (refusing to allow the United States to rescind a settlement agreement

while the issue of its approval was before the court, and holding that "the purpose

of requiring court approval is to protect the [party’s] interest-not to allow another

party to renege"), ajf’d 891 F.2d 878, 880-881, n. 3 (11th Cir. 1990) ("A settlement

is as conclusive of the rights between the parties as a judgment." . . . "Once an

agreement to settle is reached, one party may not unilaterally repudiate it.");

Fulgence v. J. Ray McDermott & Co., 662 F.2d 1207, 1209 (5th Cir. 1981)

(enforcing an oral settlement agreement in a Title VII action); Thomas v. State o f

12

La., 534 F.2d at 615 (reversing a district court order setting aside a settlement

agreement which had been reached by the parties but never approved by the court).

Likening the settlement agreement to a court-approved agreement, the Thomas

Court held, "[although no court ever approved this settlement agreement, the same

reason for enforcing a court-approved agreement — i.e., little danger of [litigants]

being disadvantaged by unequal bargaining power — applies here." Id. Similarly,

the parties’ settlement here should be enforced. Surely, there is no credible claim

that the City of Cocoa had anything less than equal bargaining power with the

seven individual African-American citizens and plaintiffs in this action.

Under Florida law, settlements are also highly favored, Utilities Comm ’n Of

New Smyrna Beach v. Florida PSC, 469 So.2d 731, 732 (Fla. 1985), and will be

upheld whenever possible, Robbie v. City o f Miami, 469 So.2d 1384, 1385 (Fla.

1985). "A stipulation properly entered into and relating to a matter upon which it

is appropriate to stipulate is binding upon the parties and upon the Court." Gunn

Plumbing, Inc. v. Dania Bank, 252 So.2d 1, 4 (Fla. 1971). "This is especially true

of settlement agreements which are highly favored in the law." Dor son v. Dor son,

393 So.2d 632, 633 (Fla. 4th DCA 1981). Accord, Lotspeich Co. v. Neogard

Corp., 416 So.2d 1163, 1164-65 (Fla. 3rd DCA 1982) ("Settlement agreements are

highly favored in the law and will be upheld whenever possible because they are

13

means of amicably resolving doubts and preventing lawsuits, . . . and should not

be invalidated or, as here, collaterally defeated by the court," (internal citations

omitted)); Crosby Forrest Products, Inc. v. Byers, 623 So.2d 565, 567 (Fla. 5th

DCA 1993) ("Settlement agreements are highly favored and once entered, are

binding upon the parties and the courts"); Wallace v. Townsell, 471 So.2d 662, 664

(Fla. 5th DCA 1985) ("The parties to a civil action have the right to settle the

controversy between them by agreement at any time and an agreement settling all

issues in the case is binding not only upon the parties but also upon the court");

Pettinelli v. Danzig, 722 F.2d 706, 710 (11th Cir. 1984) ("Florida law favors the

finality of settlements").12

B. The Parties Executed A Valid Settlement Agreement.

Defendants now argue that the City’s approval of the Consent Decree was

somehow flawed for lack of a unanimous city council vote. R2-53-3 and 5. Two

12 If this Court determines that state law governs the enforcement of the

settlement then this Court is bound by Florida appellate courts’ interpretations of

state law. Shapiro v. Associated Intern. Ins. Co., 899 F.2d 1116, 1123 (11th Cir.

1990); Floyd v. Eastern Airlines, Inc., 872 F.2d 1462, 1466-67 (11th Cir. 1989),

rev’d sub nom. on other grounds, Eastern Airlines, Inc. v. Floyd, 499 U.S. 530

(1991); Maseda v. Honda Motor Co., 861 F.2d 1248, 1257 n. 14 (11th Cir. 1988).

14

years ago, however, defendants vigorously defended the validity of the Cocoa City

Council’s consent before the district court. Defendants averred that "Cocoa’s

Consent was valid," R2-36-14; argued that "[ajmici’s claim of a lack of valid

consent is unfounded," R2-36-15; and joined plaintiffs in urging the district court

that the court, "having the power and authority to grant the relief set forth in the

Consent Decree by virtue of Cocoa’s consent and Section 2 of the Voting Rights

Act, should grant that relief." R1-29-2-3. Moreover, not once during the nearly

two years of appellate proceedings in George did defendants take the position that

the city council’s vote in May of 1994 was contrary to state law or invalid in any

other way.

Without contesting that they knowingly, willingly, and with full authority,

entered into a settlement agreement, the city changed its mind about wanting the

settlement and hired new counsel to advance its changed position. Although

defendants have new counsel (from the same law firm), their substitution of counsel

does not afford them any legal basis to change their position with regard to the

validity of the city council’s consent to the settlement or authority to settle. Daly

v. School District o f Darby Township, 434 Pa. 286, 288-289, 252 A.2d 638, 640

(1969). The law in this circuit is that litigants are bound by settlements entered

into by their lawyers. Cia Anon Venezolana De Navegacion v. Harris, 374 F.2d

15

33, 35-36 (5th Cir. 1967) (rejecting a party’s argument that "counsel for the other

parties to the litigation could not rely on the representation of [the party’s] counsel

as to his authority [to settle]" and describing such a result as "striking] at the very

basis upon which attorneys and litigants have compromised their differences for

decades."). Of course, in the case sub judice, defendants’ counsel had express

authorization to execute the settlement agreement and submit it for the court’s

approval. R2-52-Exhibit A.

C. State Law Is Not A Bar To Entry Of The Consent

Decree.

There is no requirement, under city, state or federal law, that a city council

vote unanimously before it can settle litigation to which it is a party defendant.13

lj Defendants cited Fla. Stat. §§166.031(2) and (5) in support of their

assertion, in the proceedings below, that a unanimous city council vote is required

for a valid settlement under state law. However, neither of these statutory

provisions have any bearing on the City Council’s authority to enter into a

settlement agreement in federal civil rights litigation.

Fla. Stat. § 166.031(2) requires that municipal governing bodies amend their

municipal charters whenever "a majority of electors voting in a referendum" vote

in favor of a charter amendment.

16

A settlement agreed to by a majority of the city council is legally binding on the

City of Cocoa.14 The resolution of the Cocoa City Council to enter into the

Fla. Stat. § 166.031(5) provides one method by which a municipal governing

body may, by unanimous vote, "amend provisions or language out of the charter

which has been judicially construed, either by judgment or by binding legal

precedent from a decision of a court of last resort, to be contrary to either the State

Constitution or Federal Constitution." This statutory provision does not prohibit the

city council from settling litigation to which it is a party. In fact, sub-section (3)

of the very statute cited by defendants states that Fla. Stat. §166.031 "shall be

supplemental to the provisions of all other laws relating to the amendment of

municipal charters and is not intended to diminish any substantive or procedural

power vested in any municipality by present law" Fla. Stat. §166.031(3). The city

of Cocoa has the power to enter into a settlement agreement in federal civil rights

litigation. United States v. City of Miami. Fla.. 664 F.2d 435, 439 (5th Cir. 1981)

0en banc) (Rubin, J., concurring) ("The parties to litigation may by compromise and

settlement not only save the time, expense, and psychological toll but also avert the

inevitable risk of litigation.")

14 The City’s charter states in part:

The council shall act by ordinance, resolution, motion, or

17

settlement and approve the proposed decree was adopted by "the affirmative vote

of at least three (3) members of the council," as required by Art. Ill, § 13(b) of the

Cocoa City Charter. The city charter plainly does not require unanimous vote of

the Council to approve the settlement of litigation.

Defendants have not identified any other basis for invalidating the city

council’s 1994 vote concerning the Consent Decree and defendants have not

presented a colorable argument that any provision of the city’s charter or Florida

law requires unanimous approval of a municipal governing body to enter into a

settlement agreement or join in proposing the entry of a consent decree. There

was, therefore, no basis for the district court’s Order invalidating the Consent

Decree for the second time.

That the proposed consent decree alters the method of electing the city

council without voter referendum approval is also not a bar to settlement or

enforcement of the decree. Wise v. Lipscomb, 437 U.S. 535, 544 (1978) (districting

plan proposed by city council and adopted by the Court was a legislative plan even

proclamation. No action of the council, except raising a quorum, shall

be valid or binding unless adopted by the affirmative vote of at least

three (3) members of the council . . .

City of Cocoa, Charter, Art.III, § 13(b). See Addendum Page 4.

18

where the city council had no authority under state law to amend its charter without

voter referendum approval); McDaniel v. Sanchez, 452 U.S. 130, 152-153 (1981)

(plan drafted by local legislative body is "legislative plan" for purposes of Sec. 5

preclearance, and entitled to deference, even where state law requirements not

satisfied); Tallahassee Branch o f NAACP v. Leon County, 827 F.2d 1436, 1439-

1440 (11th Cir. 1987) (giving deference to reapportionment plan adopted by county

commission despite the fact that county commission was without authority under

state law to reapportion without voter referendum approval), cert, denied, 488 U.S.

960 (1988); Straw v. Barbour County, 864 F. Supp. 1 148, 1155 (M.D. Ala. 1994)

(approving apportionment plan adopted by county commission at meeting held

without prior notice to the public required under state law); Dillard v. Crenshaw

County, 748 F. Supp. 819, 828 (M.D. Ala. 1990) ("a federal court may adopt and

implement a change in the electoral structure of a county commission proposed by

the members of that commission, even if the commission would not have the

authority under state law"); Potter v. Washington County, 653 F. Supp. 121, 123,

125-126 (N.D. Fla. 1986) (where parties submitted a proposed consent decree and

asked the Court to choose between the districting plans submitted by the parties,

districting plan proposed by county commission given deference despite fact that

county commission was without authority under state law to alter the method of

19

election absent a voter referendum); Armstrong v. Adams, 869 F.2d 410, 414 (8th

Cir. 1988) ("[Ejection commissioners had the power to agree to a remedy which

could have been imposed by the court. Any limitation of power imposed by state

law on the Board of Election Commissioners is vitiated by the authority of the

district court to remedy constitutional violations that may have occurred during the

election.")

D. Equity Requires That The Consent Decree Be Enforced.

Plaintiffs, African-American citizens and registered voters, negotiated the

terms of the Consent Decree in good faith. The district court voided the Consent

Decree because in the court’s view, the sole African-American on the city council

should have abstained from voting on the remedy to a voting rights discrimination

lawsuit because "as an African-American candidate he stood to gain inordinately

from the vote". R2-40-6. As a result, elections have continued under the very at-

large system plaintiffs have challenged as racially discriminatory. Not surprisingly,

these at-large elections have resulted in a changed composition of the city council.

It is this two-year delay in the implementation of the agreement that has resulted

in the city’s belated decision to proceed to trial rather than adhere to their

agreement. Defendants should not be permitted to use this delay - caused by the

district court’s legal error - as a device to avoid fulfilling the terms of the

20

settlement they agreed to more than two years ago. "[Allowing the government

to arbitrarily and unilaterally refuse to perform its part of the bargain would be

manifestly unjust." Reed, at 1518. This is particularly so given the egregious

circumstances of this case. After the district court invalidated the consent decree

in 1994 plaintiffs, not defendants, appealed the district court’s decision which

prohibited one of defendants from voting on the decree. While defendants

"offer[ed] no argument in opposition to the [plaintiffs’] position" in that appeal,

they left it to plaintiffs to defend the validity of the city council’s vote. George,

Brief of Appellees, p. 1. Only after this Court reversed the district court’s 1994

Order invalidating the Consent Decree did defendants change their position

regarding the legality of the city council’s vote. Furthermore, but for the district

court’s original error in invalidating the Consent Decree, the Consent Decree would

have been entered in 1994. Under these circumstances the Consent Decree should

be enforced.

II. THE CONSENT DECREE IS CONSTITUTIONAL.

Plaintiffs’ complaint alleged that the at-large system, coupled with numbered

posts, impermissibly dilutes the voting strength of African-American voters, in

violation of Sec. 2 of the Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. §1973. The seminal case

interpreting Sec. 2 is Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986). The Supreme

21

Court has consistently re-affirmed the framework for analyzing Section 2 claims set

forth in Gingles, most recently in Voinovich v. Quilter, 507 U.S. 146, 113 S. Ct.

1149 (1993) and Johnson v. DeGrandy, ___U.S.___ , 114 S. Ct. 2647 (1994). See

also Bush v. Vera, _ U .S.___, 116 S. Ct. 1941, 1969-70 (1996) (O’Connor, J.,

concurring).

Moreover, all parties filed extensive briefs addressing the application of the

Supreme Court’s 1993 decision in Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S. 630, 113 S. Ct. 2816

(1993) to the proposed Consent Decree, and the district court, following full

consideration of those briefs, concluded that there were not "any particular

problems with the decree itself', notwithstanding the decision in Shaw v. Reno.

R2-43-3. No subsequent decision of the Supreme Court, or this Court, dictates a

different result today.15

15 While settlement agreements can be modified to accommodate dramatic and

unforeseen developments, the Supreme Court has stressed that parties are not

entitled to modification whenever any new decision is handed down. "To hold that

a clarification in the law automatically opens the door for relitigation of the merits

of every affected consent decree would undermine the finality of such agreements

and could serve as a disincentive to negotiation of settlements . . . " Rufo v.

Inmates o f Suffolk County Jail, 502 U.S. 367, 389 (1992).

22

Defendants have taken the position that M[t]he consent decree, as currently

drafted no longer comports to [sic] the law in that it violates the Equal Protection

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution." R2-52-2.

Defendants’ position is premised upon their unsupported assertion that "[t]he

predominant factor motivating the [adoption of the 4-1 District Plan] . . . was the

race of the citizens effected [sic] thereby." R2-52-1. Defendants erroneously

equate "predominantly based on race" with the mere "intentional creation of

majority-minority districts".16 The Supreme Court has already rejected such a

sweeping position. Bush v. Vera, 116 S. Ct. at 1951-1952 ("strict scrutiny only

applies where ‘the State has relied on race in substantial disregard of customary and

traditional districting practices’" {quoting Miller v. Johnson, 115 S. Ct. 2475, 2497

(1995) (O’Connor, J., concurring)) and strict scrutiny "does [not] apply to all cases

of intentional creation of majority-minority districts.") As Justice O’Connor noted,

16 Defendants explained why they believe the Consent Decree is predominantly

based on race in the following manner:

It is clear from the contemplation of the parties and the demographics

utilized to form the districts in question that race was the predominant

factor in the decision making process and terms of the settlement.

R2-53-2 (emphasis added).

23

a majority of the Justices agree that:

States may intentionally create majority-minority districts, and may

otherwise take race into consideration, without coming under strict

scrutiny . . . only if traditional districting criteria are neglected, and

that neglect is predominantly due to the misuse of race, does strict

scrutiny apply.

Bush, 116 S. Ct. at 1969 (O’Connor, J., concurring) (emphasis in original). See

also Shaw v. Hunt,___U.S.___ , 116 S. Ct. 1894, 1900 (1996); Miller v. Johnson,

115 S. Ct. at 248817 ("Redistricting legislatures will, for example, almost always

be aware of racial demographics; but it does not follow that race predominates in

the redistricting process." It is only where "the legislature subordinated traditional

race-neutral districting principles, including but not limited to compactness,

contiguity, respect for political subdivisions or communities defined by actual

shared interests, to racial considerations" that race can be said to be the

"predominant factor".); DeWitt v. Wilson, 115 S. Ct. 2637 (1995), affirming 856 F.

Supp. 1409 (E.D. Cal. 1994) (affirming a district court decision rejecting a Shaw-

17 The Supreme Court emphasized that the claim in Miller was "‘analytically

distinct’ from a vote dilution claim" under Section 2. Miller, at 2485 (<quoting

Shaw, 113 S. Ct. at 2830).

24

type challenge to California’s redistricting where the plans were drawn "to

maximize the actual and potential voting strength of all geographically compact

minority groups of significant voting population," Wilson v. Eu, 4 Cal. Rptr. 2d

379, 393 (1992)). The record in this case makes abundantly clear that other

districting criteria were not "neglected" in the creation of the 4-1 District Plan, nor

were they sacrificed or subordinated to race.

The position advanced by defendants would ignore entirely Miller’s caution

that "the sensitive nature of redistricting and the presumption of good faith that

must be accorded legislative enactments, requires courts to exercise extraordinary

caution in adjudicating claims that a [legislative body] has drawn district lines on

the basis of race." Miller, 115 S. Ct. at 2488. The 4-1 District Plan, drafted by

defendants’ demographer, is a legislative plan which should be accorded deference.

R2-36-Appendix C. Far from presuming good faith, defendants’ reading of Miller

presumes invalidity of any legislative plan which includes any majority-minority

district. This position simply has no merit. "[U]ntil a claimant makes a showing

sufficient to support [an] allegation [that a districting plan is predominantly based

on race] the good faith of a state legislature must be presumed." Miller, at 2488.

Thus, the "change of law" which may, under some circumstances, justify

modification of a decree, see Rufo, has not been established here.

25

A. The Record Clearly Demonstrates That Race Was Not

The Predominant Factor In The Creation Of The 4-1

District Plan.

The demographer who developed the 4-1 District Plan for the city, Mr.

Johnson, testified that he was instructed:

to create a plan which would comply with one-person one-vote, Sec.

2 of the Voting Rights Act, Shaw v. Reno\ and protect incumbents by

splitting them up into four different districts. The City was interested

in avoiding a special election which would have been necessary had

I not been able to split all incumbents among the four districts.

R2-35-Appendix C. He further testified that "[t]he African-American community

in Cocoa is highly concentrated in the southern end of the City." Id. The

districting map allows only one conclusion; District 1, the majority African-

American district in the 4-1 District Plan, is regularly shaped, extremely compact,

and merely recognizes a large, geographically compact predominantly African-

American community.18 Cf Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30, 50 (1986).

There simply is no credible argument that the 4-1 District Plan " subordinate [s]

traditional race-neutral districting principles, including but not limited to

compactness, contiguity, respect for political subdivisions or communities defined

18 A copy of the 4-1 District Plan is attached hereto as an Addendum. See

Addendum page 1.

26

by actual shared interests, to racial considerations." Miller, 115 S. Ct. at 2488. It

is apparent from the map that the only way to avoid drawing a majority African-

American district in Cocoa would be intentionally to split the African-American

community down the middle. See Addendum page 1. Of course, such intentional

division or fragmentation of Cocoa's African-American community would itself

violate plaintiffs’ rights under Section 2 as well as the Constitution. Major v.

Treen, 574 F. Supp. 325 (E.D. La. 1983) (three judge court) (the division of

concentrated African-American population at New Orleans, Louisiana, between two

congressional districts violated Section 2); Voinovich v. Quilter, 113 S. Ct. at 1155

(vote dilution may occur where minorities are "‘dispersed] into districts in which

they constitute an ineffective minority of voters’") (,quoting Thornburg v. Gingles,

478 U.S. at 46 n. 11); Jeffers v. Clinton, 730 F. Supp. 196 (E.D. Ark. 1990) (three

judge court) aff’d mem., 498 U.S. 1019 (1991) (dilution of minority voting strength

in state legislative redistricting plan prohibited by Section 2). Avoiding unlawful

fragmentation of the city’s Black population in the development of the 4-1 Plan

was not only desirable, it was a "wholly legitimate" and compelling objective. The

testimony of the city’s demographer demonstrates that the 4-1 Plan conforms to,

rather than conflicts with the holdings of Shaw v. Reno and Miller v. Johnson.

27

In addition to the testimony of the city’s demographer and the map of the 4-1

District Plan, the language of the Consent Decree itself supports the position that

the purposes of the Consent Decree are wholly legitimate. These express purposes

included 1) "provid[ing] minority voters equal access to the political processes" and

2) "enhancing] the political participation and awareness of all citizens." Rl-29-2

[Decree] (emphasis added). This statement of objectives clearly demonstrates that

the city council did not pursue objectives which Miller condemns, but rather,

sought to achieve goals expressly allowed by Miller.

Defendants have not, and cannot, make a showing that the 4-1 District Plan

"subordinated traditional race-neutral districting principles, including but not limited

to compactness, contiguity, respect for political subdivisions or communities

defined by actual shared interests, to racial considerations" as is required in order

to trigger the application of strict scrutiny. Miller, at 2488. In fact, defendants

themselves have represented to the district court that "[district 1 is contiguous, and

it is compact", and that "[district 1 has as its core Voting Precinct 55, a precinct

of long-standing which is, and has been, majority-minority for years." R2-36-15.

Defendants have provided no justification for their changed position.19 There is

19 Indeed, the city’s most recent position is inconsistent with a number of

earlier positions it has taken before the district court and this Court. Defendants

28

absolutely no evidence to support the city’s conclusory statement that "race was the

predominant factor in the decision-making process and terms of the settlement."

R2-53-2. The 4-1 District Plan is completely in accord with the requirements of

Miller and there is no basis for defendants’ claim that the plan violates Miller

because racial considerations predominated in its construction.

represented to the district court that their motivation for moving to withdraw their

consent was their belief that the consent decree, or remedy, was violative of Miller,

but the relief they requested was that the court "order that this matter proceed to

trial on the merits". R2-53-4. The suggestion that defendants are entitled to revisit

the issue of liability under Sec. 2, even if assuming arguendo, the 4-1 District Plan

was invalid under Miller - a position plaintiffs strenuously contest - is inconsistent

with the city’s position before this Court where it argued that this Court should

remand the case to the district court for consideration of "available remedies which

do not classify any voters on the basis of race, such as limited and cumulative

voting." Appellees’ Brief in George, page 18 (emphasis added). In summarizing

their argument defendants stated "the Courts should not approve consent decrees

or enter judgments requiring single member districts until and unless it has been

demonstrated other race neutral remedies are unavailable." Appellees’ Brief in

George, page 4.

29

Not only is the record devoid of evidence that would support a Miller claim,

but the record clearly demonstrates that the Consent Decree complies with Miller

v. Johnson, and the district court had already found, prior to Miller, that that court

"[did] not have any particular problems with the decree itself' R2-43-3. Therefore,

this Court should reverse the district court’s Order and remand the case for the

limited purpose of entering the Consent Decree.

B. The Plan Embodied In The Proposed Consent Decree

Satisfies Strict Scrutiny.

For the reasons set forth above, there is no basis for concluding that the 4-1

Plan was racially gerrymandered or that the plan should be subject to strict scrutiny

under Shaw and Miller,20 Nevertheless, assuming arguendo that the proposed

Consent Decree is subject to strict scrutiny, there is no basis for concluding that the

Consent Decree would not survive such heightened judicial review and defendants

provide no argument that the 4-1 Plan does not satisfy strict scrutiny. Instead,

defendants merely conclude that "to proceed with the Joint Motion to Enter Consent

20 C f Miller at 2488 ("Where . . . race-neutral considerations are the basis for

redistricting legislation, and are not subordinated to race, a state can ‘defeat a claim

that a district has been gerrymandered on racial lines’" and thus avoid the

application of strict scrutiny) (quoting Shaw, id. at 2827).

30

Decree and Judgment at this point will violate the Equal Protection rights of those

non-African American voters in the proposed District 1 . . . " R2-53-3. Strict

scrutiny would require the districting plan to be both justified by a compelling

government interest and narrowly tailored to meet that interest. Miller, at 2482.

1. The Consent Decree Is Justified By A

Compelling Government Interest.

As defendants have already conceded, compliance with Section 2 of the

Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. §1973, is a compelling government interest.

Appellees’ Brief in George, p. 17. See also, Bush v. Vera, 116 S. Ct. at 1968

(O’Connor, J., concurring); DeWitt v. Wilson, 856 F. Supp. at 1415; cf. Johnson v.

Miller, 864 F. Supp. 1354, 1382 & n.31 (S.D. Ga. 1994) aff’d 115 S. Ct. 2475

(1995). The city was aware of the strong evidence that the existing system for the

election of city council members, interacting] with social and historical

conditions,’ impairs the ability of a protected class [under Section 2 of the Voting

Rights Act] to elect its candidate of choice on an equal basis with other voters."

Voinovich, 113 S. Ct. at 1156. R2-36-3-5.

The most important considerations in determining a Section 2 violation in a

challenge to an election structure that uses at-large elections are: 1) whether "the

minority group . . . is sufficiently large and geographically compact to constitute

31

a majority in a single-member district"; 2) whether "the minority group . . . is

politically cohesive", i.e., tends to vote as a bloc; and 3) whether "the white

majority votes sufficiently as a bloc to enable it - in the absence of special

circumstances . . . usually to defeat the minority’s preferred candidate." Gingles,

478 U.S. at 50-1. Accord Johnson v. DeGrandy, 114 S. Ct. at 2657-8.

The first consideration, that the minority group is geographically compact

such that a majority-minority district may be drawn, is established by the map of

the 4-1 District Plan and census data, both of which were incorporated in the

Consent Decree. R1-29-Attachments 1 and 2 [Decree], See also R1-35-Appendix

B and C. Defendants admitted that plaintiffs could establish this first Gingles

precondition. Rl-1-9 and R1 -13-3.

The second and third factors, that the minority community is politically

cohesive and that the majority votes as a bloc sufficiently to defeat the candidates

preferred by the minority, are established by evidence of racially polarized voting.

Gingles, 478 U.S. at 56. Plaintiffs submitted evidence in the court below of

racially polarized voting and this evidence was unrebutted by defendants.

Plaintiffs’ evidence was in the form of an affidavit from an expert witness. Rl-35-

32

Appendix D. The affidavit analyzed all elections in Cocoa since 1981,21 in which

African-American candidates were opposed by white candidates, using the same

statistical techniques used and approved in Gingles.

Defendants admitted that, prior to this litigation, only two African-Americans

had ever been elected to the Cocoa City Council and that none had been elected

since 1981. R1 -1-7 and R1 -13-2. Defendants further argued before the district

court that the city council had been advised by its lawyers, prior to entering into

the settlement, that "two of the three Gingles ‘preconditions’ were easily met: a

majority-minority single member district could be drawn in Cocoa, . . . and election

returns showed . . . there was ‘political cohesion’ amongst [black voters]". R2-36-

3.

2. The Consent Decree Is Narrowly Tailored.

There is no question that the Consent Decree, including the 4-1 District Plan,

is narrowly tailored. The plan - designed to remedy the dilutive effects of the

city’s at-large and numbered post election system - retains an at-large seat. Of the

four single-member districts, only one has a majority African-American

21 Election returns prior to 1981 were not available by precinct, making a

similar analysis of earlier elections impossible.

33

population.22 R2-53-1. The majority African-American district "has as its core

Voting Precinct 55, a precinct of long-standing which is, and has been, majority-

minority for years." R2-36-15-16. The majority African-American district is both

compact and contiguous. Id. The plan was scheduled to be implemented on a

staggered basis to allow the incumbent board members to serve out their full terms.

R1-29-5.

Since the Consent Decree is both justified by a compelling government

interest and narrowly tailored to meet that interest, it survives strict scrutiny review.

22 The 4-1 Plan does not "maximize" African-American voting strength.

African-Americans make up 28.54% of the city’s population. The 4-1 District Plan

consists of one majority African-American district out of a total of five districts,

i.e., twenty percent (20%).

34

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the district court’s Order should be reversed, and

the case remanded to the district court with instructions that that court enter the

Consent Decree.

Respectfully submitted

Cristina Correia

Laughlin McDonald

Neil Bradley

Maha Zaki

ACLU Foundation, Inc.

44 Forsyth Street, N.W.

Suite 202

Atlanta, GA 30303

404-523-2721

Fax: 404-653-0331

Elaine R. Jones

Director-Counsel

Theodore Shaw

Norman J. Chachkin

Jacqueline A. Berrien

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, Suite 1600

New York, N.Y. 10013

212-219-1900

Fax: 212-226-7592

Attorneys For Appellants

35

COLOR CODED COPY OF R l -3 5 -A p p e n d ix B.

,FL

DENOTES AREA OUTSIDE OF MUNICIPAL CORPORATE LIMITS

ADDENDUM PAGE 1

SECTION 2 OF THE VOTING RIGHTS ACT OF 1965,

TITLE 42, UNITED STATES CODE

SUBCHAPTER I-A—ENFORCEMENT OF VOTING RIGHTS

§ 1973 . Denial or abridgement of right to vote on account of

race or color through voting qualifications or p rerequ i

sites; establishment of violation

(a) No voting qualification or prerequisite to voting or standard,

practice, or procedure shall be imposed or applied by any State or

political subdivision in a m anner which results in a denial or

abridgement of the right of any citizen of the United States to vote on

account of race or color, or in contravention of the guarantees set

forth in section 1973b(f)(2) of this title, as provided in subsection (b)

of this section.

(b) A violation of subsection (a) of this section is established if,

based on the totality of circumstances, it is shown that the political

processes leading to nomination or election in the State or political

subdivision are not equally open to participation by members of a

class of citizens protected by subsection (a) of this section in that its

members have less opportunity than other members of the electorate

to participate in the political process and to elect representatives of

their choice. The extent to which members of a protected class have

been elected to office in the State or political subdivision is one

circumstance which may be considered: Provided, That nothing in

this section establishes a right to have members of a protected class

elected in numbers equal to their proportion in the population.

(Pub.L. 89-110, Title I, § 2, Aug. 6, 1965, 79 Stat. 437, redesignated Pub.L.

91-285, § 2, June 22, 1970, 84 Stat. 314, and amended Pub.L. 94-73, Title

II, § 206, Aug. 6, 1975, 89 Stat. 402; Pub.L. 97-205, § 3, June 29, 1982, 96

Stat. 134.)

Addendum Page 2

166 MUNICIPALITIES

166.031 Charier am endm ents.—

(1) The governing body of a municipality may, by

ordinance, or ihe electors oi a municipality may, by peti

tion signed by TO percent of the registered electors as

cf the last preceding municipal general election, submit

to the electors of said municipality a proposed amend

ment to its charter, which amendment may be to any

part or to all of said charter except that part describing

the boundaries of such municipality. The governing

body of the municipality shall p lace the proposed

amendment contained in the ordinance or petition to a

vote of the electors at the next general election held

within the municipality or at a special election called for

such purpose.

(2) Upon adoption of an amendment to the charter

of a municipality by a majority of the electors voting in

a referendum upon such amendment, the governing

body of said municipality shall have the amendment

incorporated into the charter and shall file the revised

charter with the Department of State. All such amend

ments are effective on the date specified therein or as

otherwise provided in the charter.

(3) A municipality may amend its charter pursuant to

this section notwithstanding any charier provisions to

the contrary. This section shall be supplemental to the

provisions cf all other laws relating to the amendment of

municipal charters and is not intended to diminish any

substantive or procedural power vested in any munici

pality by present law. A municipality may, by ordinance

and without referendum, redefine its boundaries to

include only these lands previously annexed and shall

tile said redefinition with the Department of State pursu

ant to the provisions of subsection (2).

(-) There shali be no restrictions by the municipality

on any employee's or employee group's political activity,

while not w orking , in any referendum changing

(5) A municipality may. by unanimous vote of the

governing body, abolish municipal departments pro

vided for m the municipal charter and amend provisions

or language out cf the charter which has been judicially

:d. either by judgment or by binding legal prece-c or. str i. 3 . 1 c m c i k j j u o i u j u n i U H l y I to U C I j j i c u t ; *

cent from, a decision cf a court cf last resort, to be con

trary to either the State Constitution or Federal Constitu-

iiOfi

. (6) Each municipality shall, by ordinance or charter

provision, provide procedures for filling a vacancy in

office caused by death, resignation, or removal from

office Such ordinance or charter provision shall also pro

vide procedures for filling a vacancy in candidacy

caused by death, withdrawal, or removal from the ballot

of a qualified candidate following the end of the qualify

ing period which leaves fewer than two candidates for

an office.

H i s i o r y . - s i cr w-i2r s ’ m cc-SS s i SO-105 s <3 cN 9-0-315 s

i ; cf. 9V--3S

Addendum Page 3

CITY OF COCOA

CHARTER Art. Ill, § 13

Section 13. Council Quorum; Council Votes; Council Rules.

(a) Three (3) members of the council shall constitute a quorum,

but a smaller number may adjourn from time to time and may

require the attendance of absent members in such manner and

under such penalties as the council may prescribe.

(b) The council shall act by ordinance, resolution, motion, or

proclamation. No action of the council, except raising a quorum,

shall be valid or binding unless adopted by the affirmative vote of

at least three (3) members of the council. Voting shall be accom

plished by having the presiding officer of the council request

affirmative and negative votes. Upon the request for negative

votes, all council members opposed to the question shall respond

with "nay .” The vote of each member of the council voting shall

be recorded in the minutes for such council meeting.

(c) The city council may enact rules of procedure, prescribe

penalties for a breach of same, and enforce such penalties.

Addendum Page 4

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that the foregoing Brief of Appellants was served on defense

counsel by U.S. Mail, first class postage prepaid, addressed to: J. Wesley Howze,

Jr., Esq., Amari, Theriac & Eisenmenger, P.A., Imperial Plaza, Suite B104, 6769

N. Wickham Rd., Melbourne, FL, 32940.

Done this 3rd day of December, 1996.

Cristina Correia

\