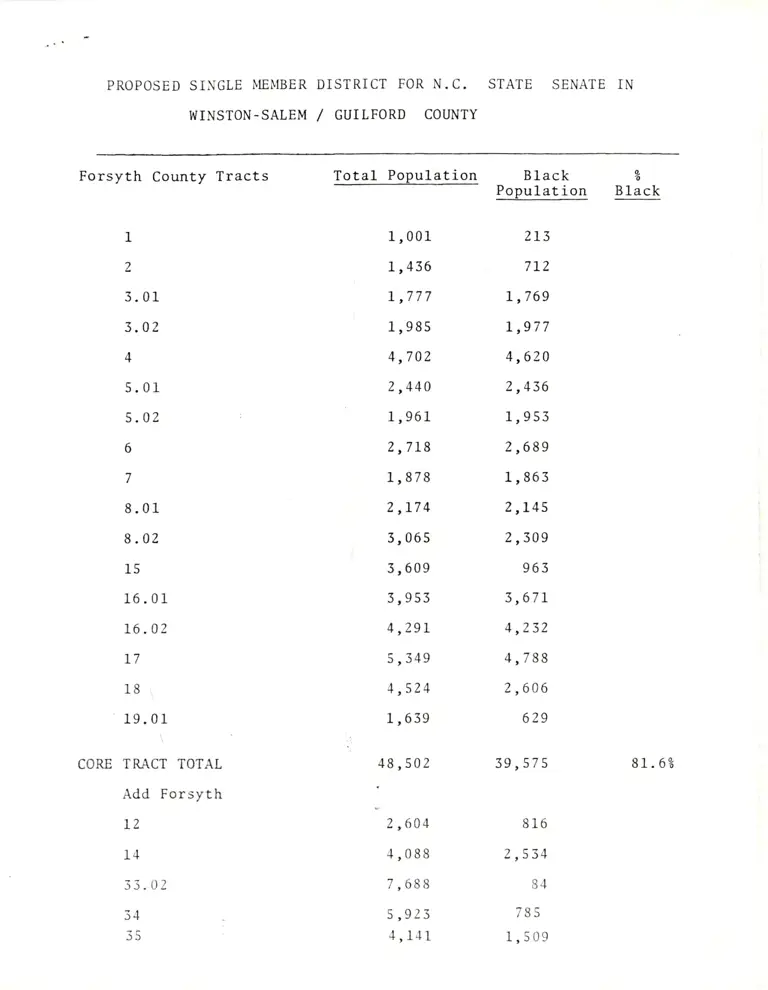

Table of Population Data for Proposed Single Member District for N.C. State Senate in Winston-Salem/Guilford Counties

Working File

January 1, 1982

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Table of Population Data for Proposed Single Member District for N.C. State Senate in Winston-Salem/Guilford Counties, 1982. 5a6f6daa-de92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d3b9fbad-aab3-4d8a-9228-1a9199972d87/table-of-population-data-for-proposed-single-member-district-for-nc-state-senate-in-winston-salemguilford-counties. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

PROPOSED SINGLE MEMBER DISTRICT FOR N.C.

WINSTON-SALEM / GUILFORD COUNTY

STATE SENATE IN

Forsyth County Tracts

CORE

1 1,001

2 1,436

3.01 1,777

3.02 1,985

4 4,702

5.01 2,440

5.02 1,961

6 2,718

7 1,878

8.01 2,174

8.02 3,065

15 3,609

16.01 3,953

16.02 4,291

17 5,349

18 4,524

19.01 1,639

TRACT TOTAL 48,502

Add Forsyth

12 ‘ 2,604

14 4,088

33.02 7,688

34 5,923

35 4,141

Total Population

Black

Population

0

6

Black

213

712

1,769

1,977

4,620

2,436

1,953

2,689

1,863

2,145

2,309

963

81.6%

Add Guilford

136.01

138

139

141

142

144.02

144.05

145.06

163

TOTAL

ADD IN FORSYTH 30

DISTRICT TOTAL

Possible Adjustment

Subtract 144.02

Add In 20.01

Alternate District

2,198

4,614

5,882

890

4,355

5,400

5,134

3,121

3,986

108,526

8,016

116,542

5,400

2,262

113,404

(-7.5)

329

3,962

5,207

619

1,687

62

453

2,072

311

60,005

2,392

62,397

62

636

62,971

55.3%

53.5%

55.5%