Zelman v. Harris Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Respondents

Public Court Documents

January 1, 2020

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Zelman v. Harris Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Respondents, 2020. c10a19ce-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d49e58a9-8d2c-4909-90d7-d19c948822d9/zelman-v-harris-brief-amicus-curiae-in-support-of-respondents. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

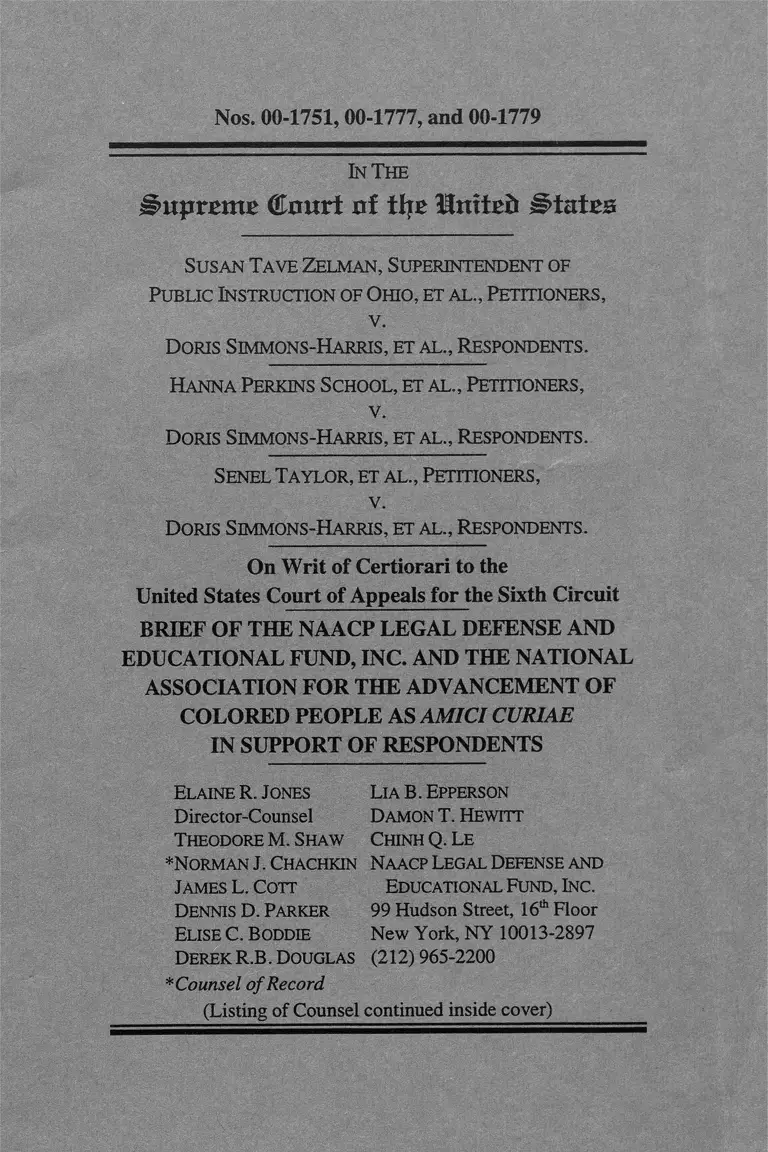

Nos. 00-1751,00-1777, and 00-1779

In The

Supreme Court of thr llrutci» sta tes

Susan Tave Zelman , Superintendent of

Public Instruction of Ohio , et a l ., Petitioners,

v.

Doris Simmons-Harris, et al ., Respondents.

Hanna Perkins School, et a l ., Petitioners,

v.

Doris Simmons-Harris, et al ., Respondents.

Senel Taylor , et a l ., Petitioners,

v.

Doris Simmons-Harris, et al ., Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

BRIEF OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC. AND THE NATIONAL

ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF

COLORED PEOPLE AS AMICI CURIAE

IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS

Elaine R. J ones Lia B . Epperson

Director-Counsel DAMON T. Hewitt

Theodore M. Shaw Chinh Q. Le

*Norman J. Chachkin Naacp Legal Defense and

James L. Cott Educational Fund, Inc.

Dennis D. Parker 99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

ELISE C. BODDIE New York, NY 10013-2897

Derek R.B. Douglas (212) 965-2200

* Counsel o f Record

(Listing of Counsel continued inside cover)_____

(Listing of Counsel continued from cover)

Dennis Courtland Hayes

General Counsel

National Association for

the Advancement of

Colored People

4805 Mt. Hope Drive, 5th Floor

Baltimore, MD 21215

(410)486-9191

Kimberly West-Faulcon

Naacp Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

Suite 1480

1055 Wilshire Boulevard

Los Angeles, CA 90017

(213)975-0211

Counsel for Amici Curiae

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Table o f A u th o ritie s .........................................................................ii

Interest o f A m ic i ........................................................ 1

Summary o f A rg u m en t.................................................................... 3

A R G U M EN T —

Introduction ......................................................................... 3

I The Voucher Program Involved In

This Action Was Neither Designed,

Nor Can It Operate, To Fulfill The

Promise Of Brown For African-

American Pupils In The Cleveland

Public Schools, The Same Class Of

Students Found By The Federal

Courts To Have Suffered From Long-

Maintained De Jure Segregation In

The Cleveland Public Schools................... 6

II Private School Tuition Voucher

Programs Such As The One Involved

In This Case Contain The Seeds Of

Educational Resegregation And Lack

Safeguards To Prevent This Result . . . . 13

C o n c lu s io n .....................................................................................18

11

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Page

Board o f Education o f Oklahoma City Public

Schools v. Dowell,

498 U.S. 237 (1 9 9 1 ) ....................................................... 15

Brown v. Board o f Education,

347 U.S. 483 (1 9 5 4 ) ................................................passim

Brown v. South Carolina State Board o f Education,

296 F. Supp. 199 (D.S.C.), a ff’dper curiam,

393 U.S. 2 2 2 (1 9 6 8 ) .................................................... 14n

Cappachione v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools,

57 F. Supp. 2d 228 (W .D.N.C. 1999),

a ff’d in part and rev’d in part en banc sub

nom. Belkv. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board

o f Education, 2001 U.S. App. LEXIS 10712

(4th Cir. 1 0 0 1 ) .....................................................................16

Coffey v. State Educational Finance Commission,

296 F. Supp. 1389 (S.D. M iss. 1 9 6 9 )..................... 14n

Columbus Board o f Education v. Penick,

443 U.S. 449 (1 9 7 9 ) ....................................................... 15

Cooper v. Aaron,

358 U.S. 1 (1 9 5 8 ) .............. 15

Dayton Board o f Education v. Brinkman,

443 U.S. 5 2 6 (1 9 7 9 ) ....................................................... 15

Ill

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (continued)

Page

Cases (continued):

DeRolph v. State,

93 Ohio St. 3d 309, 754 N .E .2d 1184 (2001) ..........2

DeRolph v. State,

89 Ohio St. 3d 1, 728 N.E .2d 993 (1999) .................2

DeRolph v. State,

78 Ohio St. 3d 193, 677 N .E .2d 733 (1997) ............ 2

Eisenberg v. Montgomery County Public Schools,

197 F.3d 123 (4th Cir. 1999), cert, denied,

146 L. Ed. 2d 312 (2 0 0 0 ) ............................................. 16

Freeman v. Pitts,

503 U.S. 467 (1 9 9 2 ) ................................. 4 ,5 ,9 , 15-16

Green v. County School Board o f New Kent County,

391 U.S. 430 (1 9 6 8 ) ...................................................... 15

Griffin v. State Board o f Education,

296 F. Supp. 1178 (E.D. Va. 1969) . . . 14n, 16n-17n

Lee v. Macon County Board o f Education,

267 F. Supp. 458 (M.D. Ala. 1 9 6 7 ) ........................ 14n

Milliken v. Bradley,

418 U.S. 7 1 7 (1 9 7 4 ) ...................................................... 15

Missouri v. Jenkins,

515 U.S. 7 0 (1 9 9 5 ) ........................................ 12n, 15, 16

IV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (continued)

Page

Cases (continued):

Poindexter v. Louisiana Financial Assistance

Commission,

275 F. Supp. 833 (E.D. La. 1967), a ff’d,

389 U.S. 571 (1 9 6 8 ) ................. ................................... 14n

Reed v. Rhodes,

662 F.2d 1219 (6th Cir. 1981), cert.

denied, 455 U.S. 1018 (1982) ...................................... 8

Reed v. Rhodes,

455 F. Supp. 569 (N.D. Ohio 1978),

a ff’d, 662 F.2d 1219 (6th Cir. 1981),

cert, denied, 455 U.S. 1018 (1982) ............ ................8

Reed v. Rhodes,

455 F. Supp. 546 (N.D. Ohio 1978),

a ff’d, 662 F.2d 1219 (6th Cir. 1981),

cert, denied, 455 U.S. 1018 (1982) .............................8

Reed v. Rhodes,

422 F. Supp. 708 (N.D. Ohio 1976), remanded

per curiam, 559 F.2d 1220 (6th Cir. 1978),

supplemental opinion on remand, 455 F. Supp.

569 (N.D. Ohio 1978), a ff’d in relevant part

and remanded on other grounds, 607 F.2d 714

(6th Cir. 1979), cert, denied, 455 U.S. 935

(1 9 8 0 ) .................................................................................. 8

San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez,

411 U.S. 1 (1 9 7 3 ) .................................................. 12n, 16

V

Cases (continued):

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board o f Education,

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (continued)

Page

402 U.S. 1 (1 9 7 1 ) .......................................................4, 15

Tuttle v. Arlington County School Board,

195 F.3d 123 (4th Cir. 1 9 9 9 ) ........................................ 16

Wessman v. Gittens,

160 F.3d 790 (1st Cir. 1 9 9 8 ) ........................................ 16

Statutes:

Ohio Rev. Code § 3313.977 ...................................................... 10

Other Authorities'.

B rief for the N A ACP Legal D efense and Educational

Fund, Inc. as Amicus Curiae in Support o f

Respondents, Adarand Constructors, Inc. v.

Mineta, 2000 U.S. Lexis 10814 (U.S. N ovem ber

27, 2001) (No. 00-730) ................................................ 14

Brian P. Gill, M ichael Timpane, K aren E. Ross, and

Dom inic J. Brewer, Rhetoric Versus Reality:

W hat W e K now and W hat W e N eed to K now

A bout Vouchers and Charter Schools (Rand

Corp. 2001), available at http://w w w .rand.org/

publications/M R/M Rl 118 (visited Dec. 9,

2001) ............................................................. lOn, 11, 14n

http://www.rand.org/

VI

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (continued)

Page

Other Authorities (continued):

Joint A ppendix, Simmons-Harris v. Zelman, 234

F.3d 945 (6th Cir. 2 0 0 0 ) .................................... 6n-7n, 9

M olly Tow nes O ’Brien, Private School Tuition

Vouchers and the Realities o f Racial

Politics, 64 Tenn. L. Rev. 359 ( 1 9 9 7 ) ............ 11, 13n

Zach Schiller, Policy M atters Ohio, Cleveland

School Vouchers: Where the Students

Come From (2001) (available at

http://w w w .policym attersohio.org)

(visited Dec. 4, 2 0 0 1 ) ........................................ .. 11

Piet van Lier & Caitlin Scott, Fewer choices,

longer commutes fo r black voucher students,

Catalyst for Cleveland Schools, Oct/N ov

2001, <http://ww w .catalyst-cleveland.org/

10-01/1001extra4.htm > (visited Nov. 27,

2001) ......................................................................... 6n-7n

http://www.policymattersohio.org

http://www.catalyst-cleveland.org/10-01/1001extra4.htm

http://www.catalyst-cleveland.org/10-01/1001extra4.htm

INTEREST OF AMICE

The NAACP Legal D efense and Educational Fund, Inc.

(“LDF”) is a non-profit corporation established under the laws

o f the State o f N ew Y ork. It was form ed to assist black persons

in securing their constitutional rights through the prosecution

o f law suits and to provide legal services to black persons

suffering injustice by reason o f racial discrim ination. For six

decades, LDF attorneys have represented parties in litigation

before this Court and the low er courts involving race

discrim ination, including in the seminal case o f Brown v. Board

o f Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

The National A ssociation for the A dvancem ent o f

Colored People (“N A A C P”), established in 1909, is the

nation’s oldest civil rights organization. It has state and local

affiliates throughout the nation. The fundam ental m ission o f

the N A A C P is the advancem ent and im provem ent o f the

political, educational, social and economic status o f m inority

groups; the elimination o f racial prejudice; the publicizing o f

adverse effects o f racial discrim ination; and the initiation o f

lawful action to secure the elim ination o f racial bias. The

N A ACP has appeared before courts throughout the nation in

num erous civil rights cases.

Throughout their existence, LDF and the N A A C P have

worked to redeem the guarantee o f equal protection o f the laws.

In no area have they placed higher priority than on education —

especially in public schools, where the overw helm ing m ajority

o f A frican-A m erican students have been and w ill continue to

be enrolled. In the struggle for an equal and quality education

*A11 parties have consented to the filing o f briefs amici

curiae in support of any party’s position. No counsel for any party

authored this brief in whole or in part, and no person or entity other

than amicus made any monetary contribution to the preparation or

submission of this brief.

2

for these pupils, the im pact o f racial segregation and

concentrated poverty have been daunting im pedim ents. N o

individuals or institutions have brought these issues to this

Court m ore often than LDF and the N A A CP, w ith the hope that

this Court w ould rem ove the barriers that im pede the process

o f undoing the effects o f centuries o f discrim ination that have

systematically and systemically lim ited educational opportunity

for A frican-A m erican children.

The enrollm ent in the Cleveland public school system

today is nearly three-quarters African-A m erican. For

generations, the Cleveland district practiced intentional racial

discrim ination and segregation that lim ited educational

opportunities for A frican-A m erican children. Today, the

system suffers from financial shortfalls associated w ith

deficiencies in O hio’s school funding m echanism , see DeRolph

v. State, 78 Ohio St. 3d 193, 677 N .E .2d 733 (1997); id., 89

Ohio St. 3d 1, 728 N .E .2d 993 (1999); id , 93 Ohio St. 3d 309,

754 N .E .2d 1184 (2001). As Petitioners’ briefs in these cases

indicate, the school system continues to struggle to provide

m inim ally adequate educational opportunities to its students, let

alone high-quality results.

A gainst this background, LDF and the N A A C P believe,

O hio’s decision to address C leveland’s desperate needs by

enacting a program that pays a lim ited am ount tow ard private

sectarian schools’ tuition charges for a lim ited num ber o f

Cleveland students raises grave dangers o f dissipating resources

that are essential to the preservation and ultim ate im provem ent

o f public education in Cleveland and o f fostering the

resegregation o f schooling in Cleveland (developm ents

com pletely inconsistent w ith the purposes o f the Brown

decisions). Because Petitioners have urged the Court to uphold

O hio’s private school voucher program on the theory that such

action will bring to fruition the goals o f Brown v. Board o f

Education, an assertion we find so unlikely as to be nearly

3

frivolous, LDF and the N A ACP file this brief in support o f the

right o f every child w ithin the Cleveland Public School System

to a quality education.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The voucher program at issue before this Court should

not be upheld against a First A m endm ent challenge on the

ground that the im provem ent it will bring to the education o f

A frican-A m erican students now attending C leveland’s public

schools outw eighs Establishm ent Clause concerns. Structural

and funding lim itations m ake hollow any hope or expectation

that the vouchers awarded by lottery to a small num ber o f

Cleveland students under this program will fulfill Brown 's

prom ise o f “equal educational opportunity” for all.

M oreover, the program — especially i f it is expanded

or m odified to loosen constraints on choice — creates serious

dangers o f increased school segregation o f publicly funded

education in the Cleveland area, particularly distressing in light

o f the long-m aintained de jure racially segregated system

previously operated by the Cleveland public schools.

ARGUMENT

Introduction

The precise issues presented in these cases involve the

perm issibility o f unrestricted state tuition assistance to

pervasively sectarian institutions offering elem entary and

secondary education. LDF and the NAACP believe that the

com pelling doctrinal considerations warranting affirm ance o f

the ruling below on those issues will be fully and adequately

presented to the Court by Respondents and other amici filing in

support o f Respondents.

W e therefore lim it our observations to one aspect o f the

grounds asserted by Petitioners to support their requests that the

4

judgm ent below be reversed. Specifically, Senel Taylor et al.,

Petitioners in No. 00-1779, seek to persuade this Court that

reversal w ould not only be consistent w ith a correct

understanding and interpretation o f the Religion Clauses o f the

First Am endm ent — but that, in addition, it w ould bring to

fruition, at long last, the “sacred prom ise o f equal educational

opportunities for all A m erican schoolchildren” that the Court

m ade to the A m erican people in Brown v. Board o f Education,

347 U.S. 483 (1954). See Br. for Taylor Petitioners, No. GO-

1779 [hereinafter, “Pet. Br.”] at 4-5.

If this assertion were even faintly well-founded, it

w ould be a pow erful practical encouragem ent to a decision in

favor o f Petitioners. The Brown ruling is regarded by nearly all

com m entators and observers o f the A m erican jud icial system

as the m ost im portant decision o f this Court in the tw entieth

century. The Court and its m em bers have expressed both

continued support for its core holding and an appreciation o f

the difficulties that have attended its effectuation. E.g.,

Freeman v. Pitts, 503 U.S. 467, 505 (1992) (Scalia, J.,

concurring) (“ [W]e m ust continue to prohibit, w ithout

qualification, all racial discrim ination in the operation o f public

schools, and to afford rem edies that elim inate not only the

discrim ination but its identified consequences.”); Swann v.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board ofEducation, 402 U .S. 1 ,13-14

(1971) (referring to history o f “ [delibera te resistance o f some

to the Court’s m andates” and “the dilatory tactics o f many

school authorities”).

The Court has further recognized the fact that the

effects o f long-m aintained racially dual school system s in this

nation have not been fully extirpated, e.g., Freeman v. Pitts,

503 U.S. at 495 (“In one sense o f the term , vestiges o f past

segregation by state decree do rem ain in our society and in our

schools. Past wrongs to the b lack race, wrongs com m itted by

the State and in its name, are a stubborn fact o f history. And

5

stubborn facts o f history linger and persist.”), even in situations

in which practical rem edies to excise them fully no longer

exist, see id., 503 U.S. at 491-92 (“ [W Jith the passage o f tim e,

the degree to which racial im balances continue to represent

vestiges o f a constitutional violation m ay diminish, and the

practicability and efficacy o f various rem edies can be evaluated

w ith m ore precision.”).

Thus, were there reason to believe that m odifying w ell-

established First A m endm ent principles would have the

ancillary effect o f bringing about substantial and lasting

im provem ent in the educational opportunities o f African-

A m erican pupils in this country, that would inevitably

constitute a subtle — but hardly insubstantial — consideration

for m em bers o f this Court, which m ust decide whether there is

adequate justification for altering its interpretation o f the

Religion C lauses.1 But the prem ise and conclusion are wrong.

'Taylor Petitioners are careful to eschew a direct appeal to

this Court on such grounds: “Petitioners do not ask this Court to

endorse parental choice as a matter of public policy, nor would it be

proper for the Court to do so.” (Pet. Br. at 6). But they follow that

statement immediately with the suggestion that if the Court

determines that the First Amendment, properly construed, requires

reversal, “the Court will affirm good-faith efforts directed toward the

constitutional imperative of extending educational opportunities to

children who need them desperately.” {Id. at 7 (emphasis added)).

This is patent rhetoric and exhortation, not just a demonstration o f

“context” (see id. at 25), and it requires a response.

6

I

The Voucher Program Involved In This

Action Was Neither Designed, Nor Can It

Operate, To Fulfill The Promise Of Brown

For African-American Pupils In The

Cleveland Public Schools, The Same Class

Of Students Found By The Federal Courts

To Have Suffered From Long-Maintained

De Jure Segregation In The Cleveland Public

Schools

Taylor Petitioners characterize this m atter as closely

reflective o f the them es and issues raised in Brown v. Board o f

Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) (Br. at 49), analogizing the

situation o f A frican-A m erican children in this country prior to

Brown — subject to the m ost pernicious forms o f official racial

discrim ination — w ith the lim itations that are im posed by the

Constitution on public support for students to attend private

schools.2 The analogy is not m erely m anipulative3 and

2“[In Brown], children were forced to travel past good

neighborhood schools to attend inferior schools because the children

happened to be black, today, many poor children are forced to travel

past good schools to attend inferior schools because the schools

happen to be private.” (Pet. Br. at 49) (emphasis added).

3For example, Taylor Petitioners mislead the Court when

they represent that a greater proportion of voucher recipients are

African-American students than are Cleveland public school

students taken as a whole (Pet. Br. at 27, citing J.A. 215a-216a).

The figures given on those pages come from a 1999 study o f the

Cleveland voucher program, see J.A. 216a n.9, but the percentages

reported in that study are based on surveys of a sample o f 505

parents of voucher recipients and 327 parents of public school

students, not upon an enumeration of all Cleveland public school and

voucher program pupils. Joint Appendix, Vol. IV, at 965, 977,

7

shallow; it is insulting to the thousands o f courageous African-

Simmons-Harris v. Zelman, 234 F.3d 945 (6th Cir. 2000). In fact,

Taylor Petitioners themselves submitted an affidavit in support of

their motion for summary judgment in the trial court reporting that

“[sjlightly over 70% of the students in the Cleveland City School

District are African-American” (Joint Appendix, Vol. II, at 468 f 11,

Simmons-Harris v. Zelman, 234 F.3d 945 (6th Cir. 2000)), and this

figure is supported by a separate study which found that 53 per cent

o f the students in the voucher program were black, compared to 71

per cent o f students in the public schools. Piet van Lier & Caitlin

Scott, Fewer choices, longer commutes for black voucher students,

Catalyst for Cleveland Schools, Oct/Nov 2001,

<http://www.catalyst-cleveland.org/10-01/1001 extra4.htm> (visited

Nov. 27, 2001).

It is also a distortion of the record in this case to suggest that

most of the students participating in the Cleveland voucher program

are attending “good” schools closer to their residences than

“ inferior” public schools to which they would otherwise be assigned.

Piet van Lier & Caitlin Scott, Fewer choices, longer commutes for

black voucher students, CATALYST FOR CLEVELAND SCHOOLS,

O ct/N ov 2001, <h ttp ://w w w .ca ta lyst-c leveland .o rg /10 -

01/1001 extra4.htm> (visitedNov. 27,2001) (“The Cleveland school

district is required to provide or pay for transportation of all voucher

students who live more than a mile from the school they attend.

About 75 percent of students using vouchers are eligible for district

transportation service because they live a mile or more from the

school they attend, estimates Mark Cegelski, planning manager for

the district’s transportation department__ [S]ome voucher students

are bused across the district on special runs that take as long as an

hour-and-a-half and include as many as three voucher schools, says

Cegelski. In contrast, the district’s return to neighborhood schools

in 1998 after the desegregation order was lifted, has meant shorter

bus rides for most public school students, transportation department

officials says [j /c] .”).

http://www.catalyst-cleveland.org/10-01/1001_extra4.htm

http://www.catalyst-cleveland.org/10-01/1001_extra4.htm

http://www.catalyst-cleveland.org/10-01/1001_extra4.htm

8

A m erican parents and students who m ade this C ourt’s Brown

decision becom e a reality, in the face o f determ ined official and

public resistance. M oreover, the Taylor Petitioners’ suggestion

that the im pedim ent to public funding o f pre-collegiate private

educational institutions that is created by the Establishm ent

C lause is the m ajor barrier today to providing equal educational

opportunities for A frican-A m erican and other children o f color

in this country, is entirely unconvincing.

For m any years, African-A m erican students in the

Cleveland public schools were the victim s o f intentionally

discrim inatory policies that isolated them in racially segregated

school facilities and lim ited their access to high-quality

educational opportunities. Reed v. Rhodes, 422 F. Supp. 708,

793 (N.D. Ohio 1976), remanded per curiam, 559 F.2d 1220

(6th Cir. 1978), supplemental opinion on remand, 455 F. Supp.

569 (N.D. Ohio 1978), a ff’d in relevant part and remanded on

other grounds, 607 F.2d 714 (6th Cir. 1979), cert, denied, 455

U.S. 935 (1980). See id., 422 F. Supp. at 793 (state

requirem ents for m inim um num ber o f hours devoted to

instruction per day waived in predom inantly black schools);

Reed v. Rhodes, 662 F.2d 1219, 1226 (6th Cir. 1981), cert,

denied, 455 U.S. 1018 (1982) (same); Reed v. Rhodes, 455 F.

Supp. 546, 565 (N.D. Ohio 1978) (inferior facilities and

educational offerings at predom inantly black high school),

a ff’d, 662 F.2d 1219 (6th Cir. 1981), cert, denied, 455 U.S.

1018 (1982); Reedv. Rhodes, 455 F. Supp. 569, 598-99 (N.D.

Ohio 1978) (low er reading scores o f black students are “m ainly

a result o f differing racial treatm ent” by school system), a ff’d,

662 F.2d 1219 (6th Cir. 1981), cert, denied, 455 U.S. 1018

(1982). Today, these students and their successors constitute

m ore than 70% o f all pupils in the C leveland public school

9

district,4 but the “stubborn facts o f history linger and persist,”

Freeman, 503 U.S. at 492. Taylor Petitioners them selves

docum ent the severe educational and operational problem s that

beset the Cleveland public schools. See Pet. Br. at 25-26.

In these circumstances, the fact that som e African-

A m erican parents in C leveland have taken advantage o f the

proffered opportunity for their children to attend non-public

schools that are not sim ilarly stigm atized as ineffectual or

burdened is hardly surprising. But the issue before the Court is

not dependent on an assessm ent o f the degree o f benefit the

program offers the lim ited num ber o f individual African-

Am erican and other C leveland students who have been able to

take advantage o f the chance to attend non-public schools.

Rather, the issues in this case m ust be judged in the context o f

a system erected by the Ohio Legislature that at once prom ises

to breach a line o f separation betw een sectarian schools and the

public fisc that has long been a part o f our nation’s basic

constitutional fabric — and also is inescapably inadequate to

deliver on Brown's prom ise o f public education free o f racial

discrim ination, and o f “equal educational opportunity” for

m inority children, see 347 U.S. at 493 (“W here the state has

undertaken to provide [an opportunity for public education], it

is a right which m ust be available to all on equal term s.”).

On that score, the num bers are telling. N o m atter how

great the level o f interest, only a small fraction o f the African-

A m erican and other m inority students, whose only real option

4Joint Appendix, Vol. II, at 468 f 11, Simmons-Harris v.

Zelman, 234 F.3d 945 (6th Cir. 2000) (Oct. 26, 1999 affidavit of

Howard Fuller submitted by Taylor Petitioners to district court in

support o f their motion for summary judgment). The lower figure

cited in Pet. Br. at 27 (45.9 per cent) is based upon a sample of 327

parents of students in Cleveland public schools in 1998, not a count

of all public school pupils. See supra note 3.

10

is to attend the public schools o f Cleveland, can be selected to

receive scholarships to attend non-public facilities under the

Legislature’s program . This is so despite the fact that the

purpose o f the program , according to Taylor Petitioners, is to

help solve the m assive educational problem s in that city.5

U nder the voucher plan involved in this case, students

w hom a local superintendent concludes are eligible because

they come from a low-incom e fam ily are given a third priority

in adm ission to private schools, after “ [sjtudents who were

enrolled in the school during the preceding year” and siblings

o f such students. The third priority preference operates only

until students from low-incom e fam ilies constitute 20 per cent

o f the total num ber o f students in a particular grade — as

determ ined by enrollm ent figures for that grade in the previous

year. Once that proportion is reached, “ [a]ll other applicants

residing anyw here,” including, presum ably, children from

higher-incom e fam ilies (as w ell as those from low-incom e

fam ilies w ho were not adm itted under the th ird priority

category) are eligible to be selected by lottery to receive a

voucher. Ohio Re v . Code § 3313.977.

The results o f this structure are not surprising. One

report found that nearly 33 per cent o f the students participating

in the Cleveland voucher program had previously attended

private schools, while only 21 per cent had gone to public

5See Brian P. Gill, Michael Timpane, Karen E. Ross,

and Dominic J. Brewer, Rhetoric Versus Reality: What We

Know and What We Need to Know About Vouchers and

Charter Schools xviii, 52,213-14 (Rand Corp. 2001), available at

http://www.rand.org/publications/MR/MR1118 (visited Dec. 9,

2001) (hereinafter cited as “RHETORIC VERSUS REALITY”)

(Cleveland’s voucher program is an “escape valve” program, “i.e,,

targeted to a smaller number of at-risk children.” “Such programs

will not be the silver bullet that will rescue urban education.”).

http://www.rand.org/publications/MR/MR1118

11

schools in Cleveland before receiving vouchers. The rem aining

46 per cent o f participants came from outside the C leveland

district or enrolled as kindergartners — and o f these latter

pupils, “at least 216, or 6 percent o f the total receiving

vouchers, were previously enrolled in preschool at private

schools that are now participating in the voucher program . . .

suggest[ing] that at least 39 per cent o f the students receiving

aid came from a private school background.” Zach Schiller,

Policy M atters Ohio, Cleveland School Vouchers: Where the

Students Come From (2001), at 2-3 (available at h ttp ://

w w w.policym attersohio.org) (visited Dec. 4, 2001).

Such lim ited efficacy is not atypical. W e are not aware

o f any voucher program that provides sufficient resources to

m ake it possible financially for all, or even m ost, pupils

attending public schools in large, urban systems w ho are from

families o f lim ited m eans to attend any private institution o f

their choice.

N o one in the voucher debate suggests that vouchers

w ould provide unlim ited choices. For exam ple, no one

suggests that vouchers would cover the full cost o f any

tu ition set by the private school. Instead, vouchers

w ould provide lim ited em powerm ent that would free

individuals who already enjoy advantage to m axim ize

that advantage. Both logic and historical experience

suggest that vouchers will exacerbate existing inequity.

M olly Townes O ’Brien, Private School Tuition Vouchers and

the Realities o f Racial Politics, 64 Tenn . L. Re v . 359, 404

(1997) (footnotes omitted). Accord, Rhetoric versus

Reality , supra note 5, at 145 (“Vouchers that fall short o f

tuition costs will have m uch lower take-up rates among low-

incom e fam ilies than will more generous vouchers”).

In short, the Legislature’s voucher program m ay

coincidentally offer some increased educational opportunities

http://www.policymattersohio.org

12

for the fortunate few students selected by lot to participate in it,

bu t it also represents a deliberate decision not to focus the

S ta te’s resources on the larger group o f children whose

educational circum stances are so severely lim ited.

The Court should, then, understand the “context” o f this

m atter w ith precision. The program at issue is not one which

offers any prom ise, or even hope, o f achieving “equal

educational opportunities” for the scores o f thousands o f

A frican-A m erican and other m inority students in the Cleveland

public schools. Instead, it is a device to open the doors for

public support o f pervasively sectarian pre-collegiate

educational institutions while ignoring the desperate

educational plight o f the mass o f A frican-A m erican and other

m inority students for whose benefit Brown v. Board o f

Education was brought and litigated.6

6It is particularly ironic for Taylor Petitioners to advance

considerations o f unequal educational outputs by poor and minority

students and a heavily poor and minority school system in support

o f reversing the judgment below. Similar arguments have been

consistently rej ected by this Court over the past generation and a half

when they were advanced, not by private schools or their students,

but by poor and minority parents and students themselves, whether

in the school finance context, see San Antonio Independent School

District v. Rodriguez, 411 U.S. 1 (1973), or in the school

desegregation context, see, e.g., Missouri v. Jenkins, 515 U.S. 70

(1995).

13

II

Private School Tuition Voucher Programs

Such As The One Involved In This Case

Contain The Seeds Of Educational

Resegregation And Lack Safeguards To

Prevent This Result

W hile the C leveland voucher program is too lim ited to

offer any realistic prom ise o f affording equal educational

opportunities to all o f the city’s African-A m erican

schoolchildren, nothing in Petitioners’ reading o f the Religion

Clauses w ould require Ohio to achieve the goal they ascribe to

the program in order to preserve its constitutionality. A t the

same tim e, the voucher program may — especially if its

targeting provisions are relaxed by the state in the future —

provide a vehicle for resegregating schooling in the Cleveland

area along racial lines; and nothing in Petitioners’ reading o f

the Religion Clauses w ould prevent Ohio from m odifying the

program in this direction. Thus, not only does the program fail

to deliver on Brown's prom ise o f equal educational quality, but

it raises the spectre o f restoring the very evil against which

Brown was directed: state-sponsored racial separation.

C leveland’s voucher program , lim ited as it m ay be at

the present time, already has facilitated white student

attendance at non-public schools in Cleveland in proportions

that exceed their representation in the public system. See supra

note 3 (white participation rate in voucher program s greater

than white share o f Cleveland public schools’ enrollment).

None o f the predom inantly white suburban school systems

surrounding the city participate in the program. A nd the limits

on tuition paym ent that the courts below found had the p rimary

effect o f directing state support overw helm ingly toward

sectarian institutions also serve to suppress m inority

14

enrollm ent, given the pow erful association betw een race and

poverty attributable to this country’s long history o f official

racial discrim ination. See B rief for the N A A C P Legal Defense

and Educational Fund, Inc. as Amicus Curiae in Support o f

Respondents, Adarand Constructors, Inc. v. Mineta, 2000 U.S.

Lexis 10814 (U.S. N ovem ber 27, 2001) (No. 00-730).

These operational characteristics o f the voucher plan

will only be accentuated and increased i f the program is

expanded,7 especially if the lim ited incom e guidelines and

priorities that now exist, see supra at 10, are relaxed in the

fu ture,8 allowing the voucher program to becom e as effective

a resegregation tool as tuition grants could have been in the

1950’s and 1960’s but for the rulings o f this Court and lower

federal courts.9

7See Rhetoric versus Reality, supra note 5, at xix

(“[L]arge-scale choice programs (whether voucher or charter) are

more likely to undermine school-level integration than are escape-

valve vouchers that put low-income children in existing private

schools.”).

%See id. at 174 (“In sum, these findings about parental

preferences suggest that unconstrained choice in a voucher or charter

program could lead to higher levels of stratification”).

9See Molly Townes O’Brien, 64 TENN. L. Rev. at 386 &

n. 179 (citing Coffey v. State Educational Finance Commission, 296

F. Supp. 1389 (S.D. Miss. 1969); Griffin v. State Board of

Education, 296 F. Supp. 1178 (E.D. Va. 1969); Brown v. South

Carolina State Board of Education, 296 F. Supp. 199 (D.S.C.), aff’d

per curiam, 393 U.S. 222 (1968); Poindexter v. Louisiana Financial

Assistance Commission, 275 F. Supp. 833 (E.D. La. 1967), aff’d, 389

U.S. 571 (1968); Lee v. Macon County Board o f Education, 267 F.

Supp. 458 (M.D. Ala. 1967)).

15

Parents o f poor and m inority schoolchildren have no

illusion that school reform and educational quality are, in the

first instance, matters lending them selves to jud icial resolution.

But the judiciary (including specifically this Court) has played

a critical role in addressing practices that perpetuate the effects

o f the racially discrim inatory policies o f the past, including

their im pact upon educational quality, c f Freeman v. Pitts, 503

U.S. at 492 (quality o f education offered m inority students is

appropriate factor to be considered in determ ining whether past

vestiges o f discrim ination had been elim inated to the extent

practicable); Missouri v. Jenkins, 515 U.S. at 101 (“The basic

task o f the District Court is to decide whether the reduction in

achievem ent by m inority students attributable to prior de jure

segregation has been rem edied to the extent practicable”). This

case presents another occasion on which the Court m ust

provide such leadership.

LDF or the N A ACP represented the p lain tiff

schoolchildren in the five cases that constituted Brown v. Board

o f Education and m any o f the m ajor cases aim ed at

im plem enting Brown's prom ise, from Cooper v. Aaron, 358

U.S. 1 (1958) through this C ourt’s m ost recent desegregation

decision, Missouri v. Jenkins, 515 U.S. 70 (1995). W hile we

have won significant victories (including in Brown, Cooper,

Green v. County School Board o f New Kent County, 391 U.S.

430 (1968), Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board o f

Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971), Columbus Board o f Education

v. Penick, 443 U.S. 449 (1979), and Dayton Board o f

Education v. Brinkman, 443 U.S. 526 (1979)), we and others

seeking to integrate public schools w ithin the U nited States

have also faced form idable obstacles. For example, this Court

has lim ited the circumstances, m eans, and duration o f

desegregation remedies. E.g., Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S.

717 (1974); Board o f Education o f Oklahoma City Public

Schools v. Dowell, 498 U.S. 237 (1991); Freeman v. Pitts, 503

16

U.S. 467 (1992); Missouri v. Jenkins, 515 U.S. 70 (1995). And

in San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez, 411

U.S. 1 (1973), this Court foreclosed federal constitutional

challenges to property tax-based school funding system s that

produce severe resource inequality betw een w ealthier and

poorer districts.

Currently, opponents o f school desegregation do not

stop at advocating further lim itations on the role o f the

judiciary; they argue that any consideration o f race, even in the

co n tex t o f fac ilita ting voluntary d eseg rega tion , is

unconstitutional, see, e.g., Wessman v. Gittens, 160 F.3d 790

(1st Cir. 1998); Tuttle v. Arlington County School Board, 195

F.3d 123 (4th Cir. 1999); Eisenberg v. Montgomery County

Public Schools, 197 F.3d 123 (4th Cir. 1999), cert, denied, 146

L. Ed. 2d 312 (2000), and even in the case o f a school system

that was long operated on a de jure segregated basis. See

Cappachione v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, 57 F. Supp.

2d 228 (W .D.N.C. 1999), a ff’d in part and rev ’d in part en

banc sub nom. Belk v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board o f

Education, 2001 U.S. App. LEXIS 10712 (4th Cir. 2001).

Ironically, in the present cases, the Petitioners invoke

race, by referring to the “sacred prom ise” o f Brown, to support

the constitutionality o f a voucher program that, as discussed

above, offers not integration, but further racial separation in

publicly funded education.10

10 Cf Griffin v. State Board of Education, 296 F. Supp. at

1181 (emphasis in original):

To repeat, our translation of the imprimatur placed

upon Poindexter by the final authority is that any assist

whatever by the State towards provision o f a racially

segregated education, exceeds the pale o f tolerance

demarked by the Constitution. In our judgment, it follows,

17

This Court should act to prevent the establishm ent o f

separate private, predom inantly white educational system s and

public, predom inantly m inority educational system s by

rejecting the Taylor Petitioners’ invocation o f Brown.

that neither motive nor purpose is an indispensable element

of the breach. The effect of the State’s contribution is a

sufficient determinant, with effect ascertained entirely

objectively.

18

Conclusion

For the reasons given above, as well as those urged by

Respondents, the judgm ent below should be affirm ed

Respectfully submitted,

Elaine R. Jones

Kimberly West-Faulcon

Naacp Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

Suite 1480

1055 Wilshire Boulevard

Los Angeles, CA 90017

(213)975-0211

Dennis Courtland Hayes

General Counsel

National Association for

the Advancement of

Colored People

Director-Counsel

Theodore M. Shaw

*Norman J. Chachkin

James L. Cott

Dennis D. Parker

EliseC.B oddie

Lia B. Epperson

Derek R.B. Douglas

Damon T. Hewitt

Chinh Q. Le

Naacp Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

4805 Mt. Hope Drive, 5th Floor New York, NY 10013-2897

Baltimore, MD 21215 (212)965-2200

(410)486-9191

*Counsel o f Record

Counsel for Amici Curiae