Smith v Allwright Brief of Appellant

Public Court Documents

April 3, 1944

6 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Smith v Allwright Brief of Appellant, 1944. d51a7ec1-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d6e833aa-46d2-4f70-b1ed-ceffc535c03b/smith-v-allwright-brief-of-appellant. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

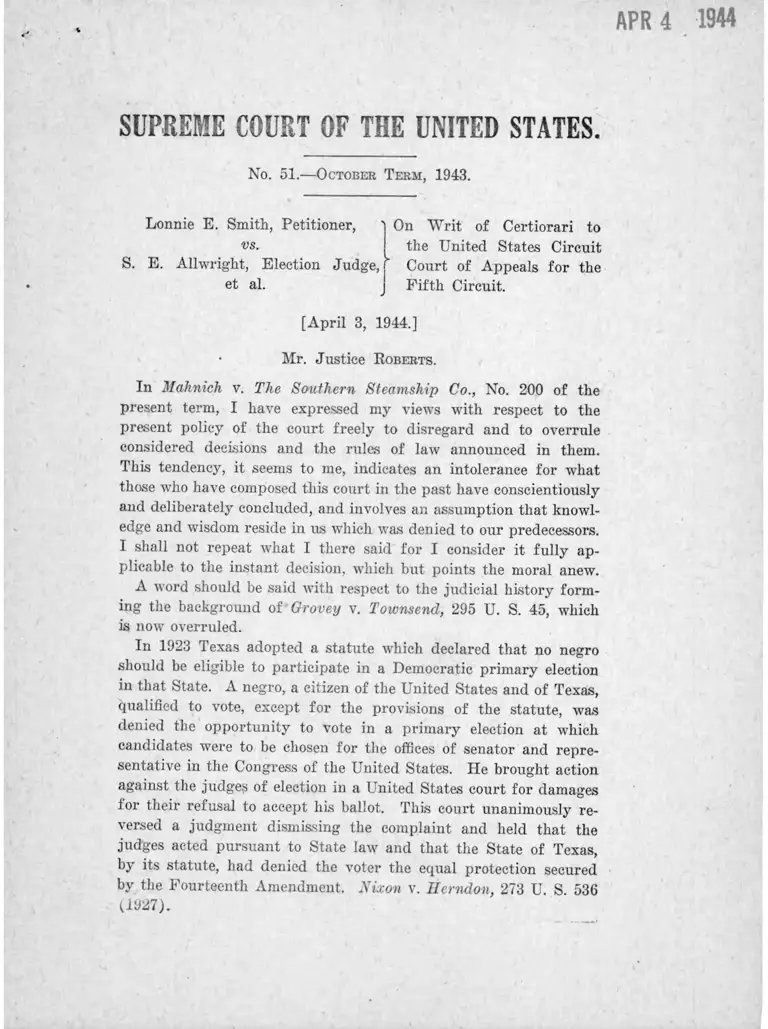

A PR 4 1944

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES.

No. 51.— October T erm, 1943.

S.

Lonnie E. Smith, Petitioner,

vs.

E. Allwright, Election Judge, "

et al.

On Writ of Certiorari to

the United States Circuit

Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit.

[April 3, 1944.]

• Mr. Justice Roberts.

In Mahnich v. The Southern Steamship Co., No. 200 of the

present term, I have expressed my views with respect to the

present policy of the court freely to disregard and to overrule

considered decisions and the rules of law announced in them.

This tendency, it seems to me, indicates an intolerance for what

those who have composed this court in the past have conscientiously

and deliberately concluded, and involves an assumption that knowl

edge and wisdom reside in us which was denied to our predecessors.

I shall not repeat what I there said for I consider it fully ap

plicable to the instant decision, which but points the moral anew.

A word should be said with respect to the judicial history form

ing the background of Grovey v. Townsend, 295 U. S. 45, which

is now overruled.

In 1923 Texas adopted a statute which declared that no negro

should be eligible to participate in a Democratic primary election

in that State. A negro, a citizen of the United States and of Texas,

qualified to vote, except for the provisions of the statute, was

denied the opportunity to vote in a primary election at which

candidates were to be chosen for the offices of senator and repre

sentative in the Congress of the United States. He brought action

against the judges of election in a United States court for damages

for their refusal to accept his ballot. This coirrt unanimously re

versed a judgment dismissing the complaint and held that the

judges acted pursuant to State law and that the State of Texas,

by its statute, had denied the voter the equal protection secured

by the Fourteenth Amendment. Nixon v. Ilerndon, 273 U. S. 536

tl927).

In 1927 the legislature of Texas repealed the provision con

demned by this court and enacted that every political party in

the State might, through its Executive Committee prescribe the

qualifications of its own members and determine in its own way

who should bd qualified to vote or participate in the party, except

that no denial of participation could be decreed by reason of

former political or other affiliation. Thereupon the State Execu

tive Committee of the Democratic Party in Texas adopted a reso

lution that white Democrats, and no other, should be allowed to

participate in the party’s primaries.

A negro, whose primary ballot was rejected pursuant to the

resolution, sought to recover damages from the judges who had

rejected it. The United States District Court dismissed his action,

and the Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed; but this court reversed

the judgment and sustained the right of action by a vote of 5 to

4. Nixon v. Condon, 286 U. S. 73 (1932).

Ihe opinion was written with care. The court refused to decide

whether a political party in Texas had inherent power to deter

mine its membership. The court said, however: “ Whatever in

herent power a State political party has to determine the content

of its membership resides in the State convention” , and referred

to the statutes of Texas to demonstrate that the State had left the

Convention free to formulate the party faith. Attention was

directed to the fact that the statute under attack did not leave

to the party convention the definition of party membership but

placed it in the party’s State Executive Committee which could

not, by any stretch of reasoning, be held to constitute the party.

The court held, therefore, that the State Executive Committee

acted solely by virtue of the statutory mandate and as delegate

of State power, and again struck down the discrimination against

negro voters as deriving force and virtue from State action,—

that is, from statute.

In 1932 the Democratic Convention of Texas adopted a reso

lution that “ all white citizens of the State of Texas who are

qualified to vote under the Constitution and laws of the state

shall be eligible to membership in the Democratic party and as

such entitled to participate in its deliberations.”

A negro voter qualified to vote in a primary election, except

for the exclusion worked by the resolution, demanded an absentee

ballot which he was entitled to mail to the judges at a primary

51

2 Smith vs. Allwriglit et al. 2

3 3

election except for the resolution. The county clerk refused to

furnish him a ballot. He brought an action for damages against

the clerk in a state court. That court, which was the tribunal

having final jurisdiction under the laws of Texas, dismissed his

complaint and he brought the case to this court for review. After

the fullest consideration by the whole court1 an opinion was

written representing its unanimous views and affirming the judg

ment. Grovey v. Townsend, 295 U. S. 45 (1935).

I believe it will not be gainsaid the case received the attention

and consideration which the questions involved demanded and

the opinion represented the views of all the justices. It appears

that those views do not now commend themselves to the court.

I shall not restate them. They are exposed in the opinion and

must stand or fall on their merits. Their soundness, however, is

not a matter which presently concerns me.

The reason for my concern is that the instant decision, over

ruling that announced about nine years ago, tends to bring adju

dications of this tribunal into the same class as a restricted rail

road ticket, good for this day and train only. I have no assur

ance, in view of current decisions, that the opinion announced

today may not shortly be repudiated and overruled by justices

who deem they have new light on the subject. In the present

term the court has overruled three cases.

In the present case, as in Mahnich v. Southern S.S. Co., No.

200, the court below' relied, as it was bound to, upon our previous

decision. As that court points out, the statutes of Texas have not

been altered since Grovey v. Townsend was decided. The same

resolution is involved as was drawn in question in Grovey v. Town

send. Not a fact differentiates that case from this except the

names of the parties.

It is suggested that Grovey v. Townsend was overruled sub

silentio in United States v. Classic, 313 U. S. 299. If so, the

situation is even worse than that exhibited by the outright re

pudiation of an earlier decision, for it is the fact that, in the

Classic case, Grovey v. Townsend was distinguished in brief and

argument by the Government without suggestion that it was

wrongly decided, and was relied on by the appellees, not as a

controlling decision, but by way of analogy. The case is not

51

Smith vs. Allwright et al.

l The court was composed of Hughes, C. J., VanDevanter, McReynolds,

Brandeis, Sutherland, Butler, Stone, Boberts and Cardozo, JJ.

mentioned in either of the opinions in the Classic ease. Again

and again it is said in the opinion of the court in that ease that

the voter who was denied the right to vote was a fully qualified

voter. In other words, there was no question of his being a person

entitled under state law to vote in the primary. The offense

charged was the fraudulent denial of his conceded right by an

election officer because of his race. Here the question is altogether

different. It is whether, in a Democratic primary, he who ten

dered his vote was a member of the Democratic Party.

I do not stop to call attention to the material differences be

tween the primary election laws of Louisiana under consideration

in the Classic case and those of Texas which are here drawn in

question. These differences were spelled out in detail in the

Government’s brief in the Classic case and emphasized in its oral

argument. It is enough to say that the Louisiana statutes re

quired the primary to be conducted by State officials and made

it a State election, whereas, under the Texas statute, the primary

is a party election conducted at the expense of members of the

party and by officials chosen by the party. If this court’s opinion

in the Classic case discloses its method of overruling earlier de

cisions, I can only protest that, in fairness, it should rather have

adopted the open and frank way of saying what it was doing

than, after the event, characterize its past ‘action as overruling

Grovey v. Townsend, though those less sapient never realized the

fact.

It is regrettable that in an era marked by doubt and confusion,

an era whose greatest need is steadfastness of thought and pur

pose, this court, which has been looked to as exhibiting consis

tency in adjudication, and a steadiness which would hold the

balance even in the face of temporary ebbs and flows of opinion,

should now itself become the breeder of fresh doubt and confusion

in the public mind as to the stability of our institutions.

51

4 Smith vs. Allwright et al. 4

mentioned in either of the opinions in the Classic case. Again

and again it is said in the opinion of the court in that case that

the voter who was denied the right to vote was a fully qualified

voter. In other words, there was no question of his being a person

entitled under state law to vote in the primary. The offense

charged was the fraudulent denial of his conceded right by an

election officer because of bis race. Here the question is altogether

different. It is whether, in a Democratic primary, he who ten

dered his vote was a member of the Democratic Party.

I do not stop to call attention to the material differences be

tween the primary election laws of Louisiana under consideration

in the Classic case and those of Texas which are here drawn in

question. These differences were spelled out in detail in the

Government’s brief in the Classic case and emphasized in its oral

argument. It is enough to say that the Louisiana statutes re

quired the primary to be conducted by State officials and made

it a State election, whereas, under the Texas statute, the primary

is a party election conducted at the expense of members of the

party and by officials chosen by the party. If this court’s opinion

in the Classic case discloses its method of overruling earlier de

cisions, I can only protest that, in fairness, it should rather have

adopted the open and frank way of saying what it was doing

than, after the event, characterize its past ‘action as overruling

Grovey v. Townsend though those less sapient never realized the

fact.

It is regrettable that in an era marked by doubt and confusion,

an era whose greatest need is steadfastness of thought and pur

pose, this court, which has been looked to as exhibiting consis

tency in adjudication, and a steadiness which would hold the

balance even in the face of temporary ebbs and flows of opinion,

should now itself become the breeder of fresh doubt and confusion

in the public mind as to the stability of our institutions.

51

4 Smith vs. Allwright et al. 4