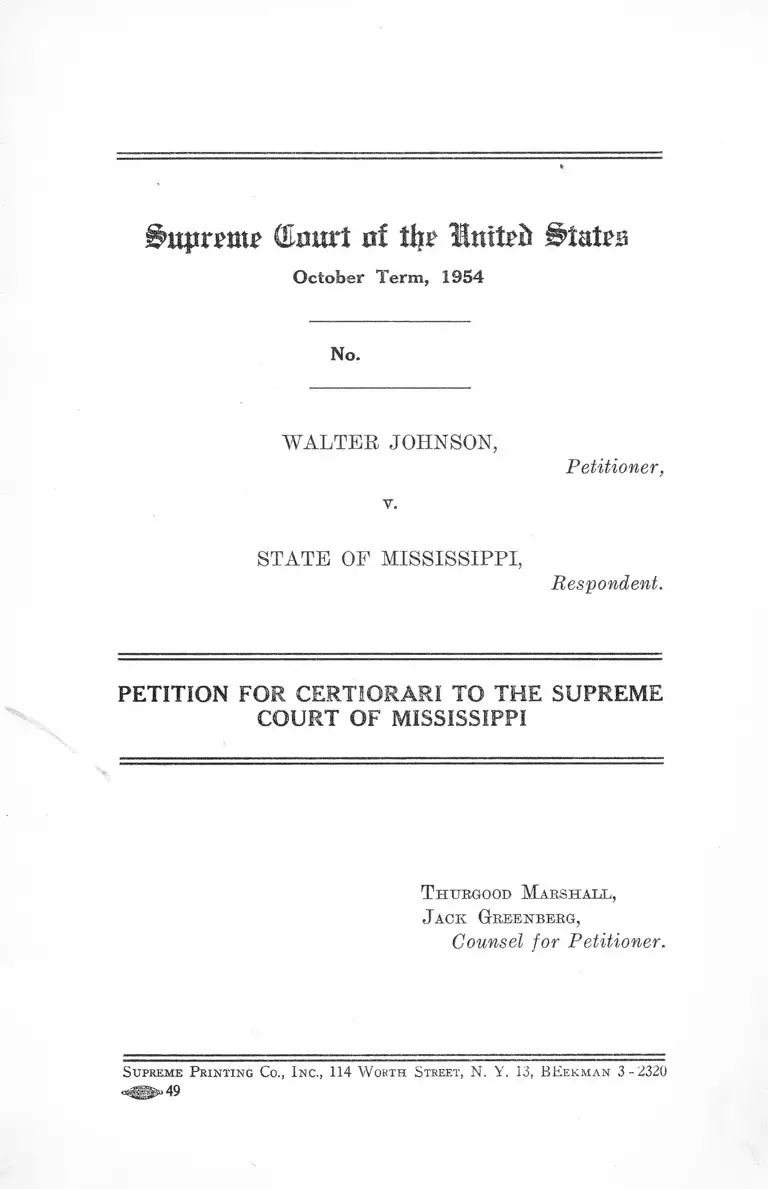

Johnsons v. Mississippi Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 4, 1954

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Johnsons v. Mississippi Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1954. 687ffb34-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d7618e2e-28d0-4016-a7a8-526f28bce749/johnsons-v-mississippi-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

(E n u r t o f ffjp H u t te d S t a t e s

O c to b e r T erm , 1954

No.

WALTER JOHNSON,

Petitioner,

V.

STATE OF MISSISSIPPI,

Respondent.

P E T IT IO N FOR CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME

COURT OF MISSISSIPPI

Thtjrgood Marshall,

J ack Greenberg,

Counsel for Petitioner.

Supreme P rinting Co., I nc., 114 W orth Street, N. Y. 13, B E ekman 3-2320

•->>■49

TABLE OF CONTENTS

, PAGE

Citations to Opinions Below .................................... 1

Jurisdiction ................................ 1

Question Presented ................................................... 2

Statement .................................................................... 3

Reasons for Granting the W r i t ................................. 4

A p p e n d ix :

Opinion of Ethridge, J ......................................... la

Table of Cases Cited

Ashcraft v. Tennessee, 322 U. S. 143 .................... 4

Chambers v. Florida, 309 U. S. 227 .......................... 4

Craig v. Harney, 331 U. S. 367 ................................. 4

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U. S. 587 ............................. 4

Patton v. State, 332 U. S. 463 ................................... 2, 7

Pierre v. Louisiana, 306 U. S. 354 ........................... 7

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303 ................ 7

Table of Statutes Cited

28 u. S. C., 1257(3) ................................................... 1

Section 1762, Mississippi Code of 1942 .................... 5

Section 1766, Mississippi Code of 1942 .................... 5, 6

Section 1772, Mississippi Code of 1942 .................... 5

Section 1779, Mississippi Code of 1942 .................... 5

Constitutional Provision

United States Constitution, Fourteenth Amendment 2, 7

Other Authority

1950 Census of Population, Vol. II, Characteristics

of the Population, part 24, Mississippi................ 6

Supreme (Eourt of % Inttpft States

October Term, 1954

No.

-------------------o-— — — ---- -—•

W alter J ohnson,

Petitioner,

v.

State of Mississippi,

Respondent.

------------------- o-------------------

PETITION FOR CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME

COURT OF MISSISSIPPI

Petitioner prays that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the Supreme Court of Mississippi entered

in the above-entitled case on January 17, 1955.

Citations to Opinions Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Mississippi,

printed in Appendix A hereto infra, page la, is reported

in 76 So. 2d (Adv. 841).

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Supreme Court of Mississippi was

entered January 17, 1955. The jurisdiction of this Court

is invoked under 28 U. S. C., 1257(3), petitioner having-

asserted in the courts below rights, privileges and immuni

ties conferred by the constitution and statutes of the

United States. Petitioner raised the question of systematic

exclusion of Negroes from grand juries in Harrison

2

County, Mississippi on motion for new trial (R. 205-224).1

The judge of the Circuit Court of Harrison County, Mis

sissippi held on the merits that there was no systematic

exclusion of Negroes from grand juries, although he stated

that “ I don’t remember too many (Negroes) serving on

the grand jury . . . ” (R. 327, 28).

The Supreme Court of Mississippi also decided against

petitioner’s constitutional claim on the merits and held

that there was no proof of systematic exclusion. It held

that “ [ajppellant also argues that there has been a sys

tematic exclusion of, and a discrimination against, Negroes

serving on the grand jury and the petit jury, in violation

of the rule in Patton v. State, 332 U. S. 463.2 . . . [n]o

Negro jurors served on the particular grand jury and petit

jury involved in this case, but appellant makes no showing

whatever that there was any systematic exclusion of the

names of Negroes from the jury box or panels.” (76 So.

2d Adv. 841, 844, Appendix, infra p. 7a).

Question Presented

Whether petitioner was denied rights guaranteed by the

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

where he has been sentenced to death following indictment

by a grand jury in a county where but two Negroes have

served on grand juries during the last 35 years.

1 “R.” refers to the Transcript of Record. The page number fol

lowing “R.” is that which appears on the bottom of the page.

2 Patton v. Mississippi, 332 U. S. 463, held that there had been a

denial of rights conferred by the Fourteenth Amendment where the

petitioner had been convicted following an indictment by grand jury

from which Negroes had been systematically excluded.

3

Statement

Petitioner, a 17-year old Negro was a member of the

Air Force, stationed at the United States Air Base, Keesler

Field, Mississippi. On March 30, 1954 a 20-year old white

resident of Mississippi and her 15-year old sister com

plained that they were accosted on a main street in Biloxi

by a Negro man in woman’s clothing and compelled to

enter a vacant shed off the street at knife point. There

the Negro “ woman” compelled the older woman to submit

to a sodomous act and then to sexual relations (E. 43-52).

Shortly after their release the young women complained

to the police. An alarm went out and a few minutes there

after petitioner was stopped for questioning at the Keesler

Air Force Base to which he was returning with a bundle of

woman’s clothing under his arm (R. 97-99). He was exam

ined and found to be wearing woman’s underclothing (R.

100). The chief clinical psychologist of the United States

Veterans Hospital in Gulfport, Mississippi later testified

on motion for new trial that petitioner is a transvestite

(E. 257), and had developed sexual deviations at an early

age, that he “ was not conscious of right and wrong” and

had a “ strong uncontrollable compulsion and a tendency to

secure pleasure on immature levels of erotic gratification”

(E. 251).

He was indicted (E. 2), tried, and convicted of the crime

of rape without recommendation of mercy (E. 17-18). The

death penalty was mandatory (E. 6).

On motion for new trial petitioner asserted denial of

his fundamental constitutional right not to be convicted of

a capital crime following indictment by a grand jury from

which members of his race had been systematically ex

cluded (E. 205-224).

The trial court (R. 327, 28) and the Supreme Court of

Mississippi (76 So. 2d 841, 844; Appendix infra p. la),

4

decided against petitioner, upon the merits, that Negroes

had not been systematically excluded from grand juries

in Harrison County.

Reasons for Granting the Writ

The decision of the Supreme Court of Mississippi is in

clear conflict with the decisions of this Court in that peti

tioner’s conviction and sentence of death were affirmed in

the face of uncontradicted testimony of systematic exclu

sion of Negroes from grand juries in Harrison County,

Mississippi.

Where there is a claim of denial of constitutional right

this Court will go behind the factual findings of the courts

below and assess that claim on the basis of the uncontra

dicted evidence. Norris v. Alabama, 294 U. S. 587, 590;

Chambers v. Florida, 309 U. S. 227, 228-229; Ashcraft v.

Tennessee, 322 U. S. 143,147-148; Craig v. Harney, 331 U. S.

367, 373-374. The uncontradicted evidence in this case is

as follows:

There was no Negro on the grand jury which indicted

petitioner (R. 208). The Clerk of the Court in which peti

tioner was tried testified that he had been Clerk for six

years (R. 205) before which he was deputy clerk for 29

years (R. 218, 220). During these 35 years he has appar

ently been present at all the empanelings of grand juries

in Harrison County (R. 220, 221, 222). On only one occa

sion during these 35 years does he recall any Negroes serv

ing on grand juries:

“By Mr. Wiggington:

Q. I believe you told Mr. Holleman that in your

recollection, I believe you said that you were Clerk

for six years but you don’t remember if it was when

you were Clerk or Deputy Clerk that you remember

5

two negroes being on the Grand Jury? A. It was

about the time or just before Mr. Ramsay died.

That’s a little more than six years.ago.

Q. Six years ago? And that is the only time that

you have recollection of negroes serving on the

Grand Jury; is that right? A. That is the only time

that I recall them serving on the Grand Ju ry” 3

(R. 219-220).

The state made no effort to contradict this testimony.

Its inquiry was merely directed to whether the two Negroes

had served six years or four years ago (R. 191). The trial

judge substantially confirmed the Clerk’s testimony in staff

3 The Clerk in selecting the Grand Jury, must choose from

names that are furnished to him by the board of supervisors of the

county. Section 1766, Mississippi Code of 1942 governs:

“How List of Jurors Procured.—The board of super

visors at the April meeting in each year, or at a subsequent

meeting if not done at the April meeting, shall select and

make a list of persons to serve as jurors in the circuit court

for the twelve months beginning more than thirty days after

wards, and as a guide in making the list they shall use the

registration book of voters, and shall select and list the names

of qualified persons of good intelligence, sound judgment, and

fair character, and shall take then as nearly as they conve

niently can, from the several supervisors district in propor

tion to the number of qualified persons in each, excluding all

who have served on the regular panel within two years, if

there be not a deficiency of jurors. The clerk of the circuit

court shall put the names from each supervisor’s district in

a separate box or compartment, kept for the purpose, which

shall be locked and kept for the purpose, which shall be locked

and kept closed and sealed, except when juries are drawn,

when the names shall be drawn from each box in regular order

until a sufficient number is drawn. The board of supervisors

shall cause the jury box to be emptied of all names therein,

and the same to be refilled from the jury list as made by them

at said meeting.”

See also §§ 1762, 1772, 1779.

6

ing that “ I don’t remember too many (Negroes) serving-

on the Grand Ju ry” (R. 327)4

In the face of the clear uncontradicted testimony, the

assertion by the Mississippi Supreme Court that “ the evi

dence offered by appellant is to the contrary and negatives

his allegations” (that Negroes were systematically ex

cluded) is incorrect.

Harrison County has a population of 13,421 non-whites

among its 70,652 whites,5 and has 1600 registered Negro

voters among 26,000 white voters (R. 212-213). It is in

credible that no Negro (with but two exceptions, six years

ago) qualified for jury service in 35 years if there were

not severe discrimination against members of that race.

In the words of this Court “ . . . if it can possibly be con

ceived that all of them were disqualified for jury service by

reason of crime, habitual drunkeness, gambling, inability

to read and write, or to meet any other or all of the statu

4 There was no testimony contradicting the fact that no other

Negroes had ever served , on Harrison County Grand Juries. The

state however tried to raise an inference that there possibly might

have been others:

“By Mr. Holleman: You wouldn’t say that was the only

time that they ever served though, would you?

By the Witness: No sir.”

In view of the Clerk’s explicit testimony and presence at the em-

panellings, this admission of a mere mathematical possibility appears

to be devoid of substantive meaning.

Neither is the uncontradicted testimony rebutted by the Clerk’s

statement that he had not been “party to” nor had he “witnessed

systematic exclusion of the members of the negro race for jury duty

in Harrison County, Mississippi” (R. 222-223). The Clerk had

to draw from lists furnished to him, and he had neither knowledge

nor responsibility concerning their composition (R. 217, 222-223).

See also Section 1766, Miss. Code of 1942, supra.

5 1950 Census of Population; Vol. II, Characteristics of the popu

lation, part 24, Mississippi.

7

tory tests, we do not doubt that the state could have proved

it.” Patton v. Mississippi, 332 U. S. 463, 468.

It has been the clear and consistent rule of the court

that a conviction of a Negro upon an indictment handed

down by a grand jury from which Negroes were sys

tematically excluded violates the 14th Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States. This proposition has

been repeatedly reaffirmed, e.g., Strauder v. West Virginia,

100 U. S. 303; Pierre v. Louisiana, 306 U. S. 354; Patton v.

Mississippi, 332 U. S. 463; Cassel v. Texas, 339 U. S. 282.

Thus the decision below conflicts with this Court’s rule.

“ When a jury selection plan, whatever it is, operates in

such a wTay as always to result in the complete and long-

continued exclusion of any representative at all from a

large group of Negroes or any other racial group, indict

ments and verdicts returned against them by juries thus

selected cannot stand,” Patton v. Mississippi, 332 U. S.

463, 469.

It is therefore clear that the decision of the Supreme

Court of Mississippi would take petitioner’s life without

due process of law and in denial of the equal protection of

the laws.

W herefore for the foregoing reasons the petition for

writ of certiorari should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

Thurgood Marshall,

J ack Greenberg,

Counsel for Petitioner.

l a

APPENDIX

Opinion of Ethridge, J.

E thbidge, Justice:

Walter Johnson, the appellant, was convicted in the

Circuit Court of Harrison County of the crime of Rape,

and was sentenced to suffer the death penalty. Code of

1942, Sec. 2358. The crime occurred around 10:30 P. M.

on the night of March 30, 1954, in the City of Biloxi, Har

rison County, Mississippi. It is undisputed that appellant

committed the offense. The prosecutrix, a young white

married woman, testified that appellant had a knife and

threatened the life of herself and her sister, with whom

she was going home, unless she submitted to his demands.

She unequivocally identified Johnson as the culprit, and

she had ample opportunity to observe him on the occasion

in question. Her sister also definitely identified appellant.

Dr. W. A. Tisdale, who examined the prosecutrix shortly

after the rape occurred, testified concerning the condition

of her body after the rape, and his examination fully con

firmed her statements. Appellant, a Negro, was a soldier

stationed at Keesler Field. Corporal Zike arrested him

when he returned to Gate Number One around 11:05 P. M.

that night, and took a knife from him. Appellant made an

oral confession to Sergeants Etheridge and Hill of the

Air Force Police, in wThich he admitted the crime and the

use of the knife which was taken from him as the instru

ment of coercion. Assistant Chief of Police Walter Wil

liams and Captain Charlie Comeaux, of the Biloxi Police

Department, testified that appellant signed two separate

written confessions of the crime, one dated March 30, 1954,

and another April 7, 1954; and that these confessions were

wholly voluntary and made without any coercion or prom

ise of leniency. They admitted appellant’s premeditated,

criminal rape of the prosecutrix. Appellant did not testify,

2a

either on the preliminary hearing concerning the confes

sions or on the merits. He offered no evidence and made

no issue as to the admissibility of the confessions. Since

there is no dispute as to the facts, we will not undertake

to outline the repulsive details of appellant’s crime.

Appellant argues that the verdict of the jury is against

the great weight of the evidence. However, this record

contains no dispute of the State’s testimony and Johnson’s

two confessions that he committed the crime. Apparently

the argument on this point is the claim that the prosecutrix

did not offer sufficient resistance to the commission of the

crime. But the record shows that she and her sister, who

was present at the time, were rendered incapable.of physi

cal resistance because of the fact that appellant had with

him a large knife with which he threatened to kill both the

prosecutrix and her sister if they resisted or cried out.

Where the act is accomplished after the female yields

through fear caused by immediate threats of great bodily

injury, there is compulsive force and the act is rape. Actual

physical force or actual physical resistance is not required

where the female yields through fear under a reasonable

apprehension of great bodily harm. Here the threats were

made before the act through the exhibition of, and threat

to use, a deadly weapon, a knife. Actual physical resist

ance by the female is not required in such circumstances.

75 C. J. 8., Rape, See. 15; Milton v. State, 142 Miss. 364,

107 So. 423 (1926); McGee v. State, 40 So. 2d. 160, 171

(Miss. 1949).

The trial court committed no error in admitting into

evidence the two confessions of appellant. It is undisputed

that appellant was fully advised as to his rights and that

he made the statements voluntarily, without coercion of

any kind. Appellant did not testify upon the preliminary

examination as to their admissibility and offered no evi

dence that such statements were not voluntary. There is

Opinion of Ethridge, J.

no evidence that he was overawed, frightened or intimi

dated by the officers, as appellant asserts.

On the voir dire examination, the juror Scarborough

had been accepted as a juror by the State. He had testified

that he had no conscientious scruples against the imposi

tion of capital punishment. While being* questioned by the

defendant’s attorney, Scarborough changed his prior testi

mony, and said that he had a strong* conviction against the

imposition of capital punishment. The court then inter

rogated him and was advised by him that he did not believe

in capital punishment. Thereupon the trial judge excused

Scarborough as a juror, and stated that he wanted the jury

to understand that the court was taking no part in the

decision on the facts, that whether appellant was guilty,

and, if so, the type punishment he should receive, were

questions for the jury, but that since Scarborough did not

believe in capital punishment, that was a disqualification

in a capital case. Appellant says that the effect of the

court’s action was to advise the jury that their readiness

to inflict capital punishment was their most important

qualification, and that this action prejudiced the jury

against appellant.

In cases where the death penalty can be imposed by a

jury, it is the duty of the judge to inquire of the jurors

whether they have conscientious convictions against inflict

ing the death penalty. Phenizee v. State, 180 Miss. 746, 178

So. 579 (1938). A somewhat similar case to the instant

one on this question is Lewis v. State, 9 S. and M. 115

(Miss. 1847). The court was performing its duty in this

respect, and committed no error in acting as it did. We

find no prejudice to appellant resulting from this incident.

Appellant made no point either before or during the

trial that he was insane and incapable of distinguishing

between right and wrong as to the particular acts with

which he was charged, or at the time of the trial. He

3a

Opinion of Ethridge, J.

4a

filed no suggestion of insanity nor any other pleading rais

ing that issue before or during the trial. He did not testify

in his own defense, and the only witness he offered was

Captain Robert W. McGill, the commanding officer of the

Student Squadron of which appellant was a member. He

testified that appellant came to the squadron on January

1, 1954, and that he is 17 years of age (18 now). He knew

nothing about the alleged crime. Appellant’s counsel asked

McGill his opinion of appellant’s mental age, and what

peculiarities he displayed. Appellant’s attorney stated that

he was not pleading insanity. After that statement the

trial court sustained an objection to those questions. If

appellant had pleaded insanity, they would have been

proper. In fact, the district attorney on the trial conceded

that. However, since in the trial on the merits appellant’s

counsel advised the court that he was not pleading insanity,

the court was not in error in sustaining that objection to

the stated questions to McGill. Appellant asked for and

obtained no instructions on the question of sanity, and did

not submit that issue to the jury.

Appellant filed a motion for a new trial, which set up

two new points not previously raised by him: (1) Newly

discovered evidence which would show that appellant was

insane at the time of the crime, during the trial, and subse

quent thereto, and that Dr. H. L. Deabler, a clinical psy

chologist, had examined appellant and made this diagnosis;

(2) that no Negroes were summoned to serve on the panel

from which the grand jury and petit jury were drawn.

On the hearing of this motion for a new trial, appellant

offered, to support his contention of insanity, Dr. H. L.

Deabler. He is the chief clinical psychologist at the Vet

erans Administration Hospital in Gulfport. The substance

of his lengthy testimony is that appellant has a gross over

development of the sexual impulse; and it has resulted in

his taking on feminine ways and being attracted to feminine

Opinion of Ethridge, J.

Opinion of Ethridge, J.

things. On the occasion of this rape, appellant was wearing

women’s clothing, including* underwear. Dr. Deabler said

that appellant had failed to develop a sense of right and

wrong or a “ healthy conscience” ; that appellant at the

time of the rape had “ a strong uncontrollable compulsion”

and therefore was not conscious of right and wrong. His

acts are characterized by transvestitism and voyeurism.

However, he stated that he had made a psycho-diagnos

tic test to determine appellant’s sanity, and that this test

showed him to be “ sane in our sense, in contact with

reality.” He was not psychotic and was not insance, from

a psychologist’s point of view, but Dr. Deabler thought

that he was legally insane, since he thought that appellant

had such an uncontrollable compulsion that he did not

know the difference between right and wrong. Appellant’s

intelligence is average for a 17-year-old boy, in terms of

ability to think, to handle school work “ and that sort of

thing.” Dr. Deabler had not read appellant’s confession

and had gained his data largely from a two-hour conference

with appellant, and from talking to his attorney. The fact

that after appellant originally approached the prosecutrix

and her sister, he walked away from them temporarily

when a truck approached, indicated a fear of being caught,

but the doctor did not believe it indicated a sense of doing

something wrong. Appellant is not suffering from any

mental disease, but a psychological disorder.

In rebuttal of this testimony, the State offered the chief

of police of Biloxi, the assistant chief of police, and a police

man, all of whom had talked with appellant on a number

of occasions since he had been in custody, and all of whom

said that in their opinions he was entirely sane and knew

the difference between right and wrong; and that they had

discussed the crime with appellant, and he appeared to

realize that what he had done was wrong. In overruling

the motion for a new trial, the court stated that in view

Opinion of Ethridge, J.

of the testimony of the State’s witnesses, the psychologist,

and his own observation of the defendant, he was satisfied

that the net result of their testimony and of the evidence

is that defendant knew right from wrong* and was and is

sane.

We think that this conclusion of the trial court is amply

warranted. This Court rejected the “ irresistible impulse”

test of sanity as early as 1879, in Cunningham v. State, 56

Miss. 269. To the same effect are Garner v. State, 112

Miss. 317, 73 So. 50 (1916); Smith v. State, 96 Miss. 786,

49 So. 945 (1909); Eatman v. State, 169 Miss. 295, 153 So.

381 (1934); Anno. 70 A. L. R. 659, and 173 A. L. R. 391; 14

Am. Jur., Criminal Law, Sec. 35; 15 Am. Jur., Criminal

Law, Sec. 327; 22 C. J. S., Criminal Law, Sec. 58. We

apply the test of the leading English case known as M’Nagh-

ten’s case, which is the majority rule. 14 Am. Jur., Crimi

nal Law, Secs. 38-40; 22 C. J. S., Criminal Law, Sec. 59;

Rogers v. State, No. 39,466, decided January 10, 1955. It

is summarized in Eatman v. State, supra:

“ In this state, as generally in the several states,

the rule of law is that the test of criminal responsi

bility is the ability of the accused, at the time he.

committed the act, to realize and appreciate the

nature and quality thereof—his ability to distinguish

right and wrong. Smith v. State, 95 Miss. 786, 49

So. 945, 946, 27 L. R. A. (N. S.) 461, Ann. Cas.,

1912A, 23. And the defense of want of inhibitory

powers, or as otherwise expressed, the defense of

irresistible or uncontrollable impulse was declared

in that case to be unavailable, unless the uncontrol

lable impulse spring from a mental disease existing

to such a high degree as to overwhelm the reason,

judgment, and conscience, in which case, as the court

adds, the accused would be unable to distinguish the

right and wrong of a matter.”

Opinion of Ethridge, J.

The testimony of appellant’s own witness, Dr. Deabler,

fails to meet these criteria. In fact, Deabler applied the

so-called irresistible impulse test, which this Court has

rejected. On the contrary, the testimony of the State’s

witnesses, who have had opportunity to form an opinion

about appellant’s sanity, amply justified the trial court’s

finding of sanity and its overruling of the motion for a

new trial. Considering' the entire record on this appeal,

including appellant’s two signed confessions with their

logical and intelligible descriptions of his crime, Ave think

that the trial court was correct in this respect, and cer

tainly it cannot be said to be manifestly wrong.

Appellant also argues that there has been a systematic

exclusion of, and a discrimination against, Negroes in serv

ing on the grand jury and the petit; jury, in violation of the

rule in Patton v. State, 332 U. S. 463, 68 S. Ct. 184, 92 L. Ed.

76, 1 A. L. R. 2d. 1286 (1947). Without detailing the testi

mony of the only witness offered on this issue, which was

not raised until the motion for new trial, it is sufficient to

say that the testimony of the Circuit Clerk of Harrison

County, Ewert Lindsey, shows without dispute that there

has been no systematic exclusion of Negroes from juries

in Harrison County, and that, in fact, at practically every

term of court Negro jurors are drawn out of the box; and

that no effort was made to discriminate either in selecting

jurors for the box or in drawing jurors. No Negro jurors

served on the particular grand jury and petit jury involved

in this case, but appellant makes no showing whatever that

there was any systematic exclusion of the names of Negroes

from the jury box or panels. In fact, the evidence offered

by appellant is to the contrary and negatives his allegation.

For these reasons the judgment of the circuit court is

affirmed.

Affirmed, and Thursday, March 3, 1955, is fixed as the

date for execution of the death sentence in the manner pro

vided by law.

Ann n in e of the judges concur.

• /-