Voting Rights Act Extension Report with Supplemental and Dissenting Views

Reports

September 15, 1981

This item is featured in:

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Voting Rights Act Extension Report with Supplemental and Dissenting Views, 1981. afc04bd6-df92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d910cc2d-22dc-418f-83e6-81fbb83511d4/voting-rights-act-extension-report-with-supplemental-and-dissenting-views. Accessed January 31, 2026.

Copied!

LAN(

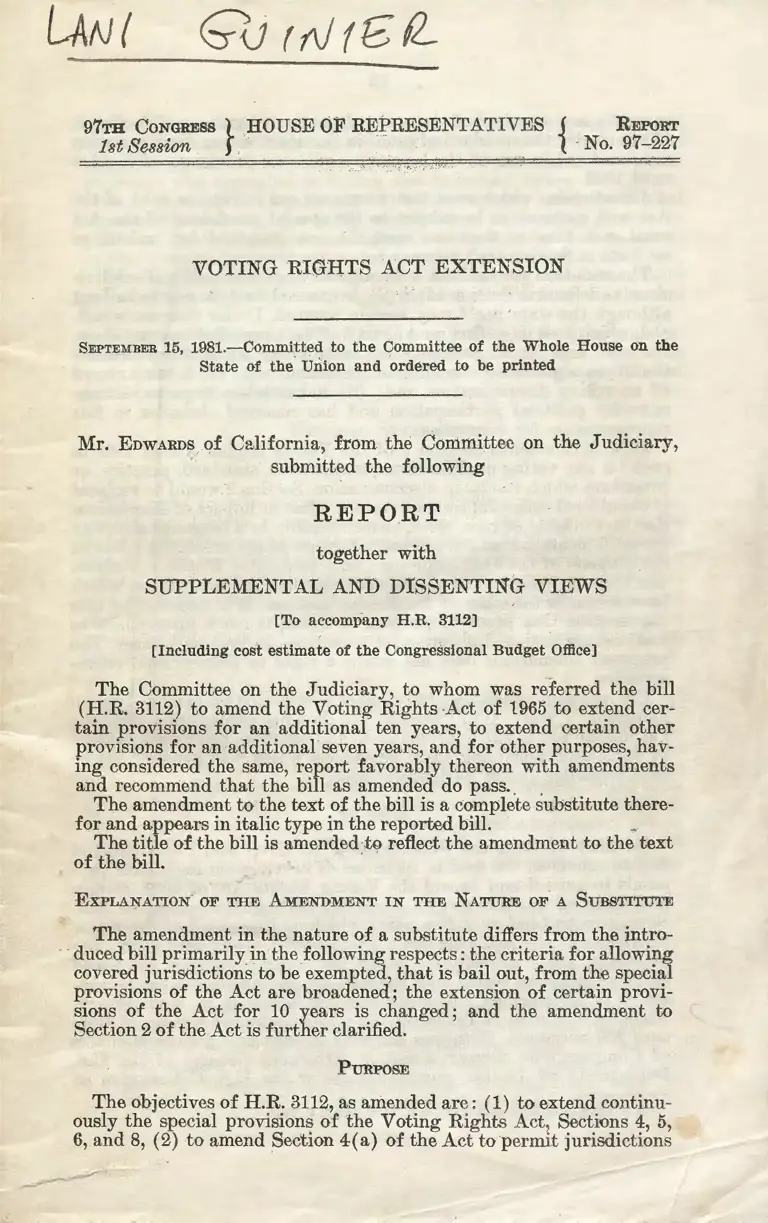

97TH CoNGRESS} HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES { REPORT

1st Session , · No. 97-227

:"· •· : ,·. ·· ·

VOTING RIGHTS ACT EXTENSION

SEPTEMBER 15, 1981.-Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the

State of the Union and 'ordered to be printed

Mr. EDWARDS of California, from the Committee on the Judiciary,

, · submitted the following

REPORT

together with

SUPPLEMENTAL AND DISSENTING VIEWS

[To accompany H.R. 3112]

[Including cost estimate of the Congressional Budget Office]

The Committee on the Judiciary, to whom was referred the bill

(H.R. 3112) to amend the Voting Rights ·Act of 1965 to extend cer

tain provisions for an additional ten years, to extend certain other

provisions for an additional seven years, and for other purposes, hav

ing considered the same, report favorably thereon with amendments

and recommend that the bill as amended do pass. . ,

The amendment to the text of the bill is a complete substitute there-

for and appears in italic type in the reported bill. _

The title of the bill is amended to reflect the amendment to the text

of the bill. ,

ExPLANATION OF THE AMENDMENT IN THE NATURE OF A SUBSTITUTE

The amendment in the nature of a substitute differs from the intra-

. duced bill primarily in the following respects: the criteria for allowing

covered jurisdictions to be exempted, that is bail out, from the special

provisions of the Act are broadened; the extension of certain provi

sions of the Act for 10 years is changed; and the amendment to -

Section 2 of the Act is further clarified.

PURPOSE

The objectives of H.R. 3112, as amended are : (1) to extend continu

ously the special provisions of the Voting Rights Act, Sections 4, 5,

6, and 8, (2) to amend Section 4(a) of the Act to permit jurisdictions

2

to meet a new standard of exemption from the obligations of Section 5,

(3) to clarify the standard of proof in Section 2 voting discrimination

cases and ( 4) to extend the language assistance provisions of the Act

until1992. ·

Jurisdictions which meet the criteria set out in Section 4(b) of the

Act will continue to be subject to the special provisions of the Act

until such time as they can ineet the new standard for bailout, as

set rorth in Section 4 (a), as amended.

The st_andard for bail-out is broadened to permit political subdivi

sions, as define<! in Section 14( c) (2), in covered states to seek to bail out

although the state itself may remain covered. Under the new stand

ard, which goes into effect on August 6,1984, a jurisdiCJtion must show,

for itself rund fur all governmental units within its territory that for

the to years preceding the filing of the bailout suit: ( 1) it has a record

of no voting discrimination and; (2) it has talren steps to increase

minority political participation and has removed obstacles to fair

representation for minorities .

. H.R. 3112 amends SectiOn. 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 to

prohibit any voting qualification, prerequisites, standard, practice, or

procedure which results in discrimination. Section 2 would be violated

if the alleged unlawful conduct has the effect or impact of discrimina

tion on the basis of race, color, or membership in a lrungu,age minority

grou:p. The amendment is necessary because of the unsettling effect of

the decision. of the U.S. Supreme Court in Oity of Mobile v. Bolden,

446 U.S. 55 (1980). The amendment clarifies the ambiguities which

have arisen in the wa;ke of the Bolden decision. It is intended by this

clarification that proof of purpose or intent is not a prerequisite to

establishing voting discrimination vio}ations in Section 2 cases. The

proposed amendment does not create a right w proportional repre

sentation.

The language assistance provisions of Section 203 are extended for an

additional 7 years. While Section 203 does not expire until 1985, the

Committee felt it was appropriate.to address these provisions in light

of legislation amending these provisions which was pending before

the Committee during its deliberations.

IfiSTORY

On May 6, 1981, the Subcommittee on Civil and Constitutional

Rights convened the first in its series of hearings on legislative pro

posals to extend . and amend the Voting Rights Act of 1965, certain

provisions of which expire on August 6, 1982. At the outset, the Sub

committee had before it five bills 1 which addressed all of the major

provisions ofthe Act, even those which do not expire next year. Con

sequently, . the Subcommittee heard testimony regarding the broad

range of issues 'connected with the Act. The Subcommittee held eight

een days of hearings, including regional hearings in Montgomery,

Alabama and Austin, Texas, during which testimony was heard from

over 100 witnesses. Witnesses included current and former Members

of Conwess; two former Assistant Attorneys General of the U.S.

Department of Justice, representatives of the U.S. Commission on

1 H.R. 3112, H .R. 3198, H.R. 1731, H.R. 1407, and H .R. 2942.

3

Civil Rights, national, state, and local civil rights leaders, State and

local government officials, representatives of various civic, union and

religious organizations, private citizens, as well as social scientists and

attorneys who specialize in voting discrimination issues. Representa

tives from the U.S. Department of Justice were invited to testify but

were unable to do so prior to the completion of the hearing process. In

addition, the Subcommittee encouraged witnesses who were unable to

appear personally to submit statements for the record.

On July 21, 1981, the Subcommittee met and by unanimous voice

vote ordered H.R. 3112 reported, without amendment, to the full

Committee.

On July 28, 30, and 31, the full Committee on th Judiciary met to

consider H.R. 3112. On July 31, the full Committee, by a vote of 23

to 1, ordered the bill reported to the House, with a single amendment

in the nature of a substitute.

GENERAL STATEMENT

BACKGROUND

The right to vote is preservative of all ooher rights. As a conse

quence, our history is replete with actions by the Congress over the

last 100 years to extend and safeguard the franchise. The Voting Rights

Aot of 1965 has been hailed as the most important civil rights bill

enacted by Congress. Unquestionably, it has been the most effective

tool for protecting ,the right to vote. The Act provides evidence of

tJhis Nation's commitment to assure thrut none of its citizens are de

prived of this most basic right guaranteed by the fourteenth and fif

teenth amendments.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965

The V orting Rights Act of 1965 was primarily designed to provide

swift, administrative relief where there was compelling evidence that,

despite 'a history o'£ litigation, racial discrimination continued to

plague the electoral process, thereby denying minorities the right

to exercise effectively their fra;nchise. The ineffectiveness of the case-

by-case litigrutive approach is documented in the case law itself, as

well as in the legislative history of voting rights legisla;tion passed

in 1957, 1960, 1964, and 1965. The U.S. Supreme Court, in South

Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301 (1966), summed up the legis

lative history as follows:

Voting suits are unusually onerous to prepare, sometimes

requiring ae many ae 6,000 man-houre spent combing through

registration records in preparation for trial. Litigation has

been exceedingly slow, in part booause of the ample oppor

tunities for delay afforded voting officials and others involved

in the proceedings. Even when favorable decisions have

finally been obtained, some of the States affected have merely

swi,tched to discriminatory devices not covered by the fed

eral decrees or have enacted difficult new tests designed to

prolong the existing disparity between white and Negro reg

istration. Alternatively, certain local officials have defied and

4

evaded court orders or have simply closed their registration

offices to freeze the voting rolls.2

Testimony during the recent hearings cited specific examples of

how the pre-1965 litigative approach was unsuccessful in eliminating

the myri,ad methods devised to keep minorities from participating

in the electoral process.3 One witness described litigation which went

on for 30 years to abolish the white primary, which was used in Texas

and elsewhere. The issue was whether blacks could be excluded from

participating .in the Democratic Party primaries, where the Demo

cratic nominaJtion for office was tantamount to election. During that

30 year period, th~ issue went to the U.S. Supreme Court four times

because after each decision, the state would enact legislative or ad

ministrative hurdles to frustrate further tJhe decision of the Court.

"The new technique had to be re-litigated until the Court concluded

in Terry v. Aaarn,s (345 U.S. 461), as it had in Lmne v. Wilson (307

U.S. 268), 'that the 15th Amendment was intended to nullify sophis

tic8Jted as well as simple-minded modes of discrimination.'" 4

Qognizant of this historical failure to guarantee the rights set forth

in the fifteenth amendment, Congress set out, in 1965, to devise legis

lation which would accomplish a twofold goal. First, based on case law

history and testimony presented to it, Congress realized that there

were specific practices and procedures which had historically been

used, as part of a pattern and practice of abuses, to prevent blacks

from participating in the electoral process. To address this problem,

Congress suspended the use of literacy tests and other devices in any

State or political subdivision where such test or device was in effect on

November 1, 1964 a;rul where less than 50 percent of voting age persons

were registered for or voted in the November 1964 presidential elec

tion. The rationale for this formula or "trigger" was that low voter

registration and participation resulted from the use of such tests or

devices.

Second, to assure that old devices for disfranchisement would not

simply be replaced by new ones, to the administrative preclearance

remedy of Section 5 of the Act was devised. Through this remedy the

Congress intended to provide an expeditious and effective review which

would assure that practices or procedures other than those directly ad

dressed in the legislation-that is, literacy tests and other devices, and

the poll tax-would not be used to thwart the will of the Congress

finally to secure the franchise for blacks.

The jurisdictions which met the trigger set forth in Section 4 (b)

of the 1965 Act were: the states of Alabama, Alaska, Georgia, Lou

isiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Virginia; forty counties in

· North Carolina; four counties in Arizoria; Honolulu County, Hawaii;

and Elmore County, Idaho.5 These jurisdictions were required to meet

2 South Carolina v. Katzenbach, supra, at P- _

: pd~e Hearings. _May 27, 1981, Herbert 0. Reid, Sr. and Jack Greenberg.

• Of these covered jurisdictions, the following successfully sued to exempt themselves

or bailout from the Act's spi'Cial coverage: Ala,ska [Alaska v. United States. Civil No. 101-

66 (D.D.C. August 17. 1966)]: Wake County, North Carolina [Wake County v. United

States, Civil No. 1198--66 (D.D:C. January 2:l. 1967)] : Elmor" County, Idaho [Elmore

County v. United States, Civil No. 320-66 (D.D.C. September 23. 1966)] : and Apache.

Navajo and Coconino Counties. Arizona [Apache County v. United States, 256 F. Supp. 903

(D.D.C. 1966) ]. It Is important to note that the Voting Rights Act does In fact provide for

such bailout or exemption on the part of a covered jurlsdi~tlon.

5

the obligations of Section 5 for five years, that is, to submit or "pre

clear'' any election-related practice or procedure which its sought to

enact or administer, if it was different from that which was in force or

effect on November 1, 1964. Submissions could be precleared either by

the Attorney General of the United States or by the U.S. District

Court for the District of Columbia.

In addition to the Section 5 preclearance provision, the 1965 Act

also authorized the Attorney General of the United States to send

:federal examiners to jurisdictions which met the Section 4 trigger for

purposes of listing eligible persons on the voting rolls, and to send

federal observers to oversee voting day activities.6

Equally important, Congress strengthened existing remedies in vot

ing discrimination cases for areas of the country other than those which

were triggered into the special provisions of the Act. The Act broadly

proscribed voting practices or procedures which deny or abridge the

right to vote because of race or color; federal courts were authorized

to order preclearance anywhere in the country if they found voting

abuses justifying equitable relief; authorization was also provided so

that federal examiners and observers could be assigned anywhere in

the country, if the courts deemed it necessary.7

.

1970 amendments

In 1969, Congress undertook to review the progress made under the

1965 Voting Rights Act, since covered jurisdiction would otherwise_ be

eligible to bailout from coverage of the special provisions of the Act in

1970. While encouraged by the progress in registration and voting

which had occurred since the passage of the Act, Congress also recog

nized that racial discrimination in voting continued to exist and that

the Section 5 preclearance provision had only been minimally enforced.

In August 1970, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act Amend

ments of 1970 (Public Law 91-285) which extended coverage of Sec

tion 5, and the other special provisions of the Act, for an additional

five years for the jurisdictions whose coverage was triggered by the

1965 Act. Congress also brought under the Act's special coverage,

states and political subdivisions which maintained a test or device oh

November 1, 1968 and which had less than a 50 percent turnout or

registration rate for the November 1968 presidential election. Lastly,

it established a five year nationwide ban on the use of literacy tests or

other devices. The newly covered jurisdictions also became subject to

the special provisions, or remedies, of the Act. Jurisdictions so affected

included: 3 counties (Bronx, Kings and New York counties) in New

York; one county in ·w·yoming; 2 counties (Monterey and Yuba coun

ties) in California; eight counties in Arizona ; four Election Districts

in Alaska; and towns in Connecticut, New Hampshire, Maine, and

Massachusetts. 8

6 See Sections 2, 3(c). 3(a), respectively.

1 These provisions (I.e. , the Section 4 trigger mechanism, Section 5 preclearance and

Sections 6 and 8, authorizing the use of federal examiners and observers) are commonly

referred to as the special provisions or remedies of the Act.

8 The State of Alaska; Elmore <County, Idaho, and Apache, Coconino, and Navajo Coun

ties in Arizona had been covered in 1965 and subsequently, released from the Act's coverage.

The 1970 amendments resulted in these areas being re-covered. However, with respect to the

State of Alaska only certain election districts were re-covered and not the entire state The

ele<:tion districts In Alaska were subsequently exempted in 1972 [ Alaska v. United States,

Civ1.1 No. 2122-71 (D.D.C. July 2, 1972)) . The three New York counties were exempted in

Anrll1972. but the exemption was rescinded and the three counties r ecovered two years later

[New York v. United States, Civil No. 2419-71 (D.D.C.) (orders of April 13, ·1972, January

10, 1974 and April 30, 1974) , afl''d 95 S. Ct. 166 (1974 (per curiam)].

6

1975 emtension

Since jurisdictions which were originally brought under the special

coverage provisions of the Voting Rights Act woud become eligible to

bail out from under such coverage on August 6, 1975, the Congress,

early that year, reviewed the progress which had occurred under the

Act. Again Congress noted the increase in voter participation among

blacks. Nevertheless Congress found that there continued to be a sig

nificant disparity between the percentage of black and white registered

voters. Moreover, Congress learned that to date Section 5 had only had

a limited impact. First, it was not until 1969 and 1971 that the U.S.

Supreme Court rendered its first decisions interpreting the scope of

Section 5. (Allen v. State Board of Elections. 393 U.S. 544); and (Per

kins v. Matthews, 400 U.S. 379). Second, the Department of .Tustice

did not issue Section 5 regulations giving guidance to coven'd juris

dictions as to their obligations under that provision, until Septem

ber 10, 1971. Lastly, it was believed preclearance would prove most

valuable in assuring that the 1980 reapportionments in the covered

jurisdictions would not result in racial gerrymandering.

In August of 1975, Congress extended the Voting Rights Act of

1965 for 7 years, so that jurisdictions originnJly subject to the speeial

provisions of the Act remained covered until August 6, 1982. Congress

also made permanent the nationwide ban on literacy tests and other

devices. which it had imposed on a temporary basis in 1970.

In addition, based on an extensive record, filled with examples of

the barriers to regi~tration and effective voting encountered bv lan

guage minority citizens in the electoral process, Congress expanded the

coveraP.:e of the Act to protect. such citizens from effective disfranchise

ment. It found that voting discrimination against language minority

citizens:

is pervasive and national in scope. Such minority citizens are

from environments in which the dominant language is other

than En!.rlish. In addition they have been denied equal educa

tional opporbmit.ies by State and local P."Overnments. resulting

in severe disabilities and continuing illiteracy in the English

lan!Yua!,!'e. The Congress further finds that. where State· and

local officill.ls condlicted elections only in English. language

minority citizPns are excluded from participating in the elec

toral process. In many areas of the country, this exdnsion is

a!,!'gravated bv acts of physical, economic, and political in

timidation. The Conp-ress declares th::~t. in order to enforce

the guarantees of the Fonrt.Penth o,nd Fifteenth AmPnclments

to the TTnited States Constitntion. it is necessary to eliminate

such discriminlltion by prohihitin.q: English-only elections,

and by prescribing other remedial devices.9

While coo:niz~>.nt of the breRiHh of votinl! nic;rrimination Pxist.ing

against surh citizens. ConP."rPSS n.lso rero!!Ilized that the severitv of the

nrohlems niffPred ll.rr0PS the count.rv. Conspquentlv, in exna.ndin!!' the

Act .. two distinct trigO'ers were develoned to assi1re that areas· with

different barriers to the f1lll particination o:f language minorities in

the electoral process would not be subject to the same remedies.

• 43 U.S.C. 1973 a.

7

To proscribe discrimination which, in many cases, was as egregous

as that outlined in 1965,'° Congress amended the definition of "test

or device" to include the use of .English-only election materials in juris

dictions where a single language minority group comprised more than

5 percent of the voting age population. It then extended coverage of

t.he Act to those jurisdictions which had used a test or device as of No

vember I, 1972 and had registration or voter turnout rates less than 50

percent. Jurisdictions meeting this trigger and thus subject to the spe

cial provisions of the Act, including precleal"ance, were the States of

Alaska, Arizona, and Texas; 2 counties in California; 1 county in

Colorado; 5 counties in Florida; 2 townships in Michigan; 1 county

in North Carolina; and 3 counties in South Dakota.

Where discrimination in voting against language minority citizens

was less severe, although still disturbing, Congress required that lan

guage assistance be provided throughout the electoral process where

members of a single language minority comprise more than 5 percent

of the voting age population and the illiteracy rate of such persons as a

group is higher than the national illiteracy rate. Jurisdictions covered

under this second trigger were: alll43 counties in Texas were individ

ually covered under this trigger; all 32 coun~ies in New Mexico; all

14 counties in Arizona; 39 counties in California; 34 in Colorado;

and 25 in Oklahoma.

PROGRESS UNDER THE ACT

The Committee recognizes that there has been much progress in

increasing registration and voting rates for minorities since the pas

sage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965; its sometimes dramatic suc

cesses demonstrates most clearly that it has been the most effective

tool for protecting voting rights.

Prior to 1965, the precentage of black registered voters in the now

covered states was 29 percent; registration for whites stood at 73

percent.

Today, in many of the states covered by the Act, more than half

the eligible black citizens of voting age are registered, and in some

states the number is even higher. Likewise, in Texas, registration

among Hispanics has increased by two-thirds.

In much the same manner that progress can be seen in increased

!'egistration rates for minorities covered under the Act, improvements

m the election of minority elected officials have also occurred.U

In July 1980, a total of 2,042 blacks held elective office in Southern

States covered by the Act, compared with 964 six years ago. And in

Texas and other southwestem areas first covered in 1975, Hispanics

and blacks have been elected to office in many cities and counties for

the first time. In Texas, particularly, there has been a 30 percent in

crease in the number of Hispanics elected officials between 197(). and

19RO.

Y e~ these gains are fragile. The registration figures for minorities

remam substantially lower than those for white voters.

1o See 1975 Hearing Record .

11 19Rl Report of U.S. Commission on Ch-11 Ri,::hts. Supra. See also Rolando Rlos

"The Voting Ri,::hts A~t: Its Effect In T<>xas." Ap~ll 1981, n. 2, submitted b~· William

Vela~quez, Executiye Director, Southwest Voter Reg1stration Education Project (May 6th

Hearmg).

8

The evidence is similar for the jurisdictions covered in 1975. Exam

ple, ·· in two covered South Dakota counties, 77.3 percent of whites

were registered but only 52.7 percent of American Indians were reg

istered. In Arizona, registration rate for whites was 71.5 percent but

48 percent for American Indians and 60.9 percent for Hispanics.

Lastly, in New York's three covered counties, 69.8 percent of whites

were registered as compared to a rate for Hispanics of 51.4 percentY

The number of minority elected officials is still a fraction of the

t~tal number of elected officials; there are many jurisdictions w~th

large minority populations which have no minority elected officials

and which have never had any.13 As Table 1, below, shows, only 5

percent Of elected officials in the southern covered states are black, in

an area where 26 percent of the population isblack.14

12 1981 Report of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Supra.

13 See generally, Rolando Rios, "The Voting Rights Act: Its Ell'ect In Texas," supra;

Testimony of Joaquin Avila, General Counsel, Mexican American Legal Defense and

Educatl()n Fund (MALDEF) .

14 See. Hearings, June 17, 1981, Eddie Williams, President of the Joint Center for

Political Studies.

Table 1

Number and Percent of Black Elected Officials

In States Originally Covered by the Voting Rights Act, 1968 and 1980*

Percent of Percent of

Number of Elective Number of Elective

Number of Black Offices Number of Black Offices

Percent Elective Elected Held by Elective Elected Held by

Black Offices Officials Blacks Offices Officials Blacks

State Population 1968 1968 1968 1980 1980 1980

Alabama 24.5 4,060 24 .59 4,151 238 5.73

Georgia 26.2 7,226 21 . 29 6,660 249 3.74

Louisiana 29.6 4,761 37 .78 4,710 363 7.71

Mississippi 35.1 4,761 29 . 61 5,271 387 7. 34

North Caro 1 ina 21.5 5,504 10 . 18 5,295 247 4.66

South Carolina 31.0 3,078 11 . 36 3,225 238 7. 38

Virginia 18. 7 3,587 24 . 67 3,041 91 2.99

TOTAL 25.83 32,977 .ill. ~ 32,353 1,813 5. 60

*Source: National Roster of Black Elected Officials--1980. Joint Center for Political Studies, Washington, D.C.

10

\

Even where minorities have been elected, figures can be deceptive.

Most o£ these elected officials are concentratedin local positions. Not

withstanding the highly publicized election o£ black mayors in large

cities, Table 2 clearly indicates that the overwhelming number o£

black mayors are chief executives o£ towns which are all black or

nearly so. For example, . blacks hold 70 mayoral positions in these

covered states; o£ these, 35 are in towns with a population o£ under

1,000 and which is 80 percent black.15

State

AL

GA

LA

MS

sc

TX

VA

TOTAL

Table 2

Population Distribution of Cities with Black Mayors

Within States Totally Covered by the Voting Rights Act

# of Cities TOTAL POPULATION % BLACK POPULATION

With Number of Cities With Number of Cities With

Black Mayors A Total Population Of: A Black Population Of:

Under 1000- Over Under 60- 80% or

1000 3000 3000 60% 79% More

15 8 2 5 1 6 8

6 3 1 2 2 4 0

11 4 3 4 3 3 5

17 10 6 1 0 7 10

13 11 0 2 3 2 8

5 3 0 2 0 0 5

_l _Q _Q _l _l _Q _Q

70 39 12 19 12 22 36

55.7) (17 . 1) (27.1) (17 .1) (31.4) (51 . 4)

Source : National Roster of Black Elected Officials, 1980. JCPS, Vol. 10.

U.S . Census Bureau, Corrections to Advance Reports PHC80-V, 1980 .

15 Testimony of Eddie Williams, Supra.

11

As is evident from this review of the progress which has taken place

under the Act, particularly since the 1975 extension, there is much to be

hopeful about. At the same time, discrimination continues today to

affect the ability of minorities to participate effectively within the

political process.

The Committee notes

that electoral gains by minorities since 1965 have not taken

on such a permanence as to render them immune to attempts

by opponents of equality to diminish their political influ

ence.18

(I) t is too early to conclude that the effects of decades of

discrimination against blacks and other minorities have been

eradicated and that they are now in a position to compete in

the political arena against non-minorities on an equal basis

without the assistance of the Voting Rights Act.17

COMPLIANCE WITH TRE ACT

Section 5 review is designed to .deter discriminatory voting changes

and ferret out measures which 'could undercut minority voter partici

pation and dilute minority voting strength. Approximately 900 juris

dictions in 23 fully or partially covered states are required to submit

voting changes. .

Thirty-five thousand voting changes have been submitted to the

Attorney General for preclearance under Section 5 since 1965. The

overwhelming majority, 30,000, were submitted between 1975 apd 1980.

Objections have been interposed to roughly 800 changes over the life of

the Act; more than 500 have been interposed since 1975. Almost all of

the states have had as many objections interposed within the last five

years as had been filed against them in the preceding ten years. These

changes touch upon every aspect of the electoral process, as shown by

the chart below.

1a See Hearings, July 13, 1981 , Drew Days, III, former U.S. Assistant Attorney General,

Department of Justice).

17 I d.

NUMBER OF CHANGES TO WHICH OBJECTIONS HAVE BEEN

INTERPOSED BY THE DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE BY TYPE

AND YEAR FROM 1965 - -FEBRUARY 28, 1981

1965 1970

to to

1969 1:2.IL_ 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 TOTAL

TYPE OF CHANGE

REDISTRICTING 55 ll ll 3 12 2 9 103

ANNEXATION 9 86 68 55 l 15 9 l 243

POLLING PLACE 12 3 2 7 2 4 30

PRECINCT 5 2 7

REREGISTRATION OR VOTER

PURGE l l l 3

INCORPORATION l l 3 5 1-'

t-.:)

BILINGUAL PROCEDURES 3 2 l 6

METHOD OF ELECTION 4 145 31 61 38 24 l7 14 3 334

FORM OF GOVERNMENT 4 l l l 1 2 10

CONSOLIDATION OR DIVISION

OF POLITICAL UNITS l l l 2 l l 7

SPECIAL ELECTION l l l l 3 7

VOTING METHODS 1 1 2

CANDIDATE QUALIFICATION 2 5 2 l l ll

VOTER REGISTRATION

PROCEDURE , 1 4 l l 2 9

MISCELLANEOUS 14 8 l 3 2 4 2 34

TOTALS 22 251 138 151 104 49 45 51 4 811

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division, Voting Section, February, 1981,

13

This is hardly a complete picture since not all election changes

which have a discriminatory effect have been submitted to the At

torney General or to the D.C. District Court for review, as required

by Section 5. A number of covered jurisdictions continue to defy the

Act by either failing to submit changes or boldly implementing others

to which objections have been interposed by the Attorney General.

Although the Department lacks an independent mechanism to

monitor voting changes, the Attorney General has attempted to use

several methods to identify unsubmitted changes including the exist

ing preclearance process, unsolicited notification of changes from ag

gneved persons, and review of voting rights litigation by private

parties. Upon receipt of any information that the jurisdiction has

made a voting-connected change within the meaning of Section 5, the

Department sends a "please submit" letter to the jurisdiction indi

cating the changes are legally unenforceable unless precleared. In

1980, the Department sent 124 such letters.18

Many covered jurisdictions made changes shortly after passage of

the 1965 Act, a number of which went unreviewed until recentlyY In

Georgia, enforcement suits filed between 1976 and 1980 against Dooly,

Miller, Calhoun, Clay, Early and Morgan counties required those

jurisdictions to implement less discriminatory district elections rather

than the at-large elections instituted in 1965 without preclearance.20

A 1981 court order required Clio, Alabama to preclear annexations

made in 1967 and 1976. The two ignored the Attorney General's 1976

please submit request and continued to hold illegal municipal elec-

6ons as recently as 1980.21 Responding to a 1975 please submit request

from the Attorney General, officials of Indianola, Mississippi acknowl

edged having made annexations without preclearance in 1966 and 1967

but failed to identify a 1965 annexation which doubled the white pop

ulation and significantly dilutedl)lack voting strength for the next 16

years. Litigation brought in 1980 finally enforced Section 5.22

In Texas, minorities have used the Act to insure Section 5 enforce

ment. After two Section 5 enforcement suits and two letters of ob

jection, Medina County-with a Chicano population of 43.4 percent

in 1980- finally acquiesced to a non-discriminatory redistricting plan

which enabled Chicanos to participate meaningfully in the political

process.

Other jurisdictions continue to ignore objections interposed by the

Attorney General. Sumter County, Georgia refuses to honor a 1973

objection to an at-large method of electing the school Board. And a

1976 objection to the Edgefield County, South Carolina at-large elec

tion law goes unheeded.23

CoNTINUED VoTING RIGHTS DrscRIMI:YATION

rr:he Voting Rights Act was designed in 1965 to provide a speedy

review mechanism to correct existing Fifteenth Amendment violations

and to prevent future voting discrimination. Extensive testimony was

18 "The Voting Rights Act: Unfulfilled Goals" , a Report of the U.S. Commission on Civil

Rights, September 1981, p. 194. -

19 Hearings, July 13, 1981, Drew S. Days, III.

20 Hearings, June 3, 1981, Laughlin McDonald.

21 Id., Abigail Turner.

22 Hearings, J une 12, 1981, Charles Victor 1\fcTeer.

23 Hearings, 1\fay 13, 1981, Jessie Jack.son.

14

presented detailing the variety of methods used by inventive registrars

and other state officials to keep racial minorities off the voting rolls and

out of the voting booths. · ·

As to those pockets of voting discrimination outside the covered

jurisdictions the Act strengthened the remedies available through

voting rights litigation. As the court noted in South Carolina v. Katz

enbach, "(l) egistlation need not deal with all phases of a problem in

the same way, so long as the distinction d:rawn have some basis in prac

tical experience. 24

Despite the gains in increased minority registration and voting and

in the number of minority elected officials, the Committee has observed,

during each consideration of the extension of the Act, continued manip

ulation of registration procedures and the electoral process which

effectively exclude minority participation from all stages of the polit

ical process.

The observable consequence of exclusion from government to the

minority communities in the covered jurisdictions has been (1) fewer

services from government agencies, (2) failure to secure a share of

local government employment, (3) disproportionate allocation of

funds, location and type of capital projects, ( 4) lack of equal access to

health and safety related services, as well as sports and recreational

facilities, ( 5) less than equal benefit from the use of funds for cultural

facilities, and (6) location of undesirable facilities, e.g., garbage

dumps, or dog pounds, in minority areas.25

A study conducted by the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights on the

enforcement of the Act since 1975, further buttresses the Committee's

findings that voting violations are still occurring with shocking fre

quency.26 For the purposes of this report, only some violations will be

high-lighted.

DISCRIMINATION IN REGISTRATION AND VOTING

Hearings on H.R. 3112 indicate that there are numerous practices

and procedures which act as continued barriers to registration and

voting.

These practices include: inconvenient location and hours of regis

tration, dual registration for county and city elections, refusal to ap

point minority registration and election officials, intimidation and

harassment, frequent and unnecessary purgings and burdensome re

registration requirements, and failure to provide or abusive manipula

tion of assistance to illiterates.

The U.S. Commission on Civil .Rights reports that questioning by

registration officials, especially if the official's attitude was "nasty"

could easily deter some blacks from registering, because "they are

scared of whites asking them questions. They (especially some of the

older population) still remember the way t.hings used to be to register

and having to go through a lot of questions reminds them of those

times." 27 ·

'"F/nuf/1 Ca.rolina Y. Katzenbach, supra. at I!HS.

25 Hearings, June 3, 1981, Dr. Brian Sherman; U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, State

Advisory Committee Report, Laure! and Laure!: A City Divided (1981) .

2• U.S. Commission on Civil Rights "The Voting Rights Act: Unfulfilled Goals: ·Septem

ber, 1981.

2; U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, supra, at 55.

15

Intimidation of voters was also reported in W rightsVliHe, Georgia

(.Johnson County). A well-known black community leader who as

sisted black voters reported an incident in which blacks were accused

by the election official of "blocking the entrance . to the courthouse,"

which is the polling place. When he explained that he and the other

blacks were standing an acceptable distance from the polling place, the

election official called the state troopers to get them to leave. The

respondent continued standing in front of the courthouse, and the

election official called the sheriff and state troopers again. The re

spondent said that Federal Observers from the Department of Justice

who were monitoring the 'activities told the official that he was not

bJ·eaking the law. "Later, some white men in a truck stopped in front

of the polling place. Guns were visible in the truck." 28 They began

heckling black people at the polls. The blacks left the scene (some of

them potential voters) while whites were not harassed by the official or

the white men. An incident such as the one in Wrightsville discourages

minorities from voting.

Evidence of intimidation and harassment was also found in Phoenix,

Alabama, where Arthur Sumbry was convicted and sentenced to four

years tor unauthorized voter registration. Mr. Sumbray was assisting

his pregnant wife, a deputy registrar.29 Similar evidence exists in

Pickens County, which has a black population of 42 percent. Sixty

seven percent of the eligible whites are registered; the county refuses

to appoint deputy registrars; voting registrars have called the sheriff

when groups of blacks have come to register, the sheriff has remained

throughout their registration.30

New elections were ordered in Clio, Alabama in a suit brought in

March, 1981, to enforce Section 5. A black candidate who had lost

in the 1980 council election by five votes and was a candidate in the

new council election believed she faced serious economic problems

because of her candidacy. A loan secured by a second mortgage on

her home from the only bank in the town was ordered to be made

current two weeks before the town council election. The president of

the bank called her with the notice; he has also been the Mayor of Clio

for the past 25 years. After she filed an election contest in State court,

the Mayor came to her house about the note. 31

In 1975 the State of Texas, pursuant to Section 5, submitted a bill

to the Attorney General requiring purging and re-registration. The

bill reqnired a purge of all currently registered voters and terminated

the registration of those who failed to re-register by March 1, 1976.

The Attorney General objected to the change. He found that the

purge had a potentially discriminatory effect:

'Vith regard to cognizable minority groups in Texas,

namely, black and Mexican-Americans, a study of their his

torical voting problems and a review of statistical data, in

cluding that relating to literacy, disclose that a total voter

registration purge under existing circumstances may have a

discriminatory effect on their voting rights .. . Moreover,

•• U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, supra, p. 75.

20 Hearings, June 1981, Joh n Nettles.

ao I d., Abigail Turner.

"ld.

16

representations have been made to this office that a require

ment that everyone register anew, on the heels of registra

tion .difficulties experienced in the past, could cause significant

frustration and result in creating voter apathy among

minority citizens . . .

Given these circumstances, the Attorney General stressed that:

We are unable to conclude . . . that implementation of

such a purge in Texas will not have the effect of discriminat

ing on account of race or color and language minority status. 32

The Civil Rights Commission noted that frequently discriminatory

practices and procedures are implemented when black political par

ticipatiOn is perceived as threatening to the status quo.33 Witnesses

from Alabama reported that it is no accident that five of the seven

counties designated for re-registration in 1981 are in the "black belt."

These re-registration bills are passed hy the legislature as local legis

lation under "Gentlemen's Agreements." The State Representative of

Perry County, in the black belt, won his last election by 82 votes. The

sponsor of the Wilcox and Lowndes Counties' hill exempted the pre

dominantly white counties in his district fvom compliance with the

registration bill.

Another Alabama witness contrasted re-identification bills, where

the burden was on elections officials, e.g. Jefferson County, and where

the burden was on the voter, e.g., Choctaw County. In Jefferson

County, which has a black representative in the legislature, the over

all registration for 'blacks and whites increased by 10 percent follow

ing the 1979 voter re-identification. In Choctaw County, white regis

tration declined by 22 percent and black registration by 47 percent

following the 1978 voter re-registration.

The proposed Sumter County re-registration bill is similar to Choc

taw's. Forty-five percent of this rural county's (50 miles long 'and 30

miles wide) population is below the p<>verty level; sixty-nine percent

of the population is 'black; the illiteracy rate is high.-The bill requires

notice of the re-registration in the local newspaper, the hours are lim

ited to 9 to 4 and re-registration can only occur in the precinct or heat

where the voter resides.34

An extensive purge of Wilcox County voter rolls was oonduoted in

1980. This county has been designated for re-identification in 1981.

Wilcox is in the black belt.

In Humboldt County, Nevada, registrars refused to register Indians

for failing to properly fill out registration cards; non-Indians were

not subjected to the same scrutiny.35

Witnesses described dual registration requirements in Mississippi 36

and Georgia 37 and dual re-identification requirements for voters in

some areas of Virginia. 38 Most often registration sites are some dis

tance apart.

32 U:S. Commission on Civil Rights, supra, p. 65.

32 Hearings, June 16, 1981. Raymond Brown.

34 Hearings, June 3, 1981. Eddie Hardaway. John Nettles, and Abigail Turner.

""U.S. v. Humboldt County, Nevada, Civil Actlo!l'No:-R 70-0144 HEC (D. Nev. 1970.) .

•• Hearings, 1\iay 28. 1981. Rims Barber.

•• Hearings, June 3, 1981, Laughlin McDonald.

38 Ibid., May 20, 1981, Michael Brown. -

17

Witnesses from Alabama and Georgia described the failure of elec

tions officials to appoint additiOIIl!al registrars. In 1980, Dekalb County,

Georgia officials adopted a policy to stop requests by community

groups to conduct voter registration drives. Eighty-one percent of the

eligible whites in the county were registered by only 24 percent of the

eligible black v;oters. The League of Women Voters brought a Sec

tion 5 enforcement suit. The district court ruled the policy was a

change withirn the meaning of Section 5. An objection was interposed

by the Attorney General.

A 1980 appeal from rthe Governor of Alabama to all boards of regis

trars urging appointment of deputy registrars and expanded registra

tion hours has reportedly generated little positive response.39

In 1981 a bill was introduced in the Alabama Senate to appoint city

clerks as voting registrars at the request of the municipal governing

body, thereby expanding registration opportunities. An amendment

was offered by the representative from Wilcox and Lowndes Counties

to exempt ten counties in the black belt from this expanded voting

procedure.

Existing and changed locations of polling places can have a negative

effect on minority voter turnout. For example, in Hopewell, Virginia,

blacks are concerned about voting at the Veterans of Foreign Wars

(VFW) Hall located in the white community. According to the presi

dent of the Virginia chapter of the Southern Christian Leadership

Conference, there are no voting places in the black community. The

present location is "like having the polls at a country club." Accord

ingly, "if one precinct was in the black community, then black people

might become more accustomed to voting.~' 40

In October 1979, the Board of Commissioners submitted a polling

place change in the city of 'Iaylor in Williamson County, Texas, to the

Attorney General. According to the Department of Justice, the polling

place would be moved from the "centrally located" City Hall to the

National Guard Armory which is located "approximately ten to twelve

blocks !fOrth of City Hall in a predominantly white area." The Depart

ment concluded that the new polling place would be "a significant

inconvenience to the city's minority voters who may appear to be

concentrated in the southern and southwestern portions of the city ...

[and] may have ... the effect of deterring participation by some

minority voters in elections ... " The Attorney General was unable

to conclude that the polling place change would not have the effect of

discriminating against minorities. 41

DISCRIMINATION IN THE ELECTORAL PROCESS

The Congress and the courts have long recognized that protection of

the franchise extends beyond mere prohibition of official actions

designed to keep voters away from the polls, it also includes prohibi

tion of state actions which so manipulate the elections process as Ito

render voters meaningless.

"The right to vote can be affected by a dilution of voting power as

well as by an absolute prohibition on casting a ballot." 42 Certain kinds

"'Hearings. June 3. 1981, Ahlgail Turner.

40 U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, supra, p. 75.

"Id., at p. 77 .

., A !len v. State Board of Elections, 393 U.S. 544 569 (1969), Reynolds v. Sims, jl77 u.s. 533, 555 (1964). •

H.Rept. 97-227 --- 3

18

of practices or changes, can nullify minorities' ability to elect the

candidate of their choice just as would prohibiting some of them from

voting.43

There are a number of practices and procedures in the electoral

process which individually or in combination result in inhibiting or

diluting minority political participation and voting strength. Since

the passage of the Act in 1965, reports presented by the U.S. Commis

sion on Civil Rights 44 studies conducted by sociala,nd political scien

tists,45 and Congressional hearings 46 have all identified discriminatory

elements of the elections process such as at-laTge elections, high fees

and bonding requirements, shifts from elective to appointive office,

majority vote run-off requirements, numbered posts, staggered terms,

full slate voting requirements, residency requirements, annexations/

retrocessions, incorporations, and malapportionment and racial gerry-

Although these elections practices or devices are used throughout

the country, in the covered jurisdictions, where there is severe racially

polarized voting, they often dilute emerging minority political

strength. In fact many of these devices were used to limit political

participation of newly enfranchised blacks more than a century ago.

Thus, effectively barring minorities from electing the candidate of

their choice.

The Committee heard numerous examples of how at-large elections

are one of the most effective methods of diluting minority strength in

the covered jurisdictions. Frequently, this method of election is com

bined with devices such as anti7single shot voting, majority vote, num

bered posts, residency restrictions and staggered terms. In Clark

County, Alabama, the County Commission ( 4 Commissioners, 1 pro

bate judge) was elected for 4-year terms from single-member districts.

A majority vote was required for nomination in the Democratic pri

mary. Blacks constituted 44 percent of the county population (1970

Census) yet no black had ever been elected to the county Commission.

In 1971 the county shifted to an at-large system of elections; the

county's Section 5 submission was not completed until1978. The county

claimed the shift to the at-large scheme was necessary to comply with

the one-person-one-vote requirement. It offered no explanation of why

this could not be done by redistricting the pre-existing single-member

district system. The Department of Justice objected to the change .

.. Allen v. State Board of Elections, supra.

"U.S. Commission on Civil Rights : Political Participation (1968) ; The Voting Ri9hts

Act: Ten Years After (1975) ; The Voting Rights Act: Unfulfilled Goals (1981) .

.. E.g .. C. Davidson and G. Korbel, At-Large Elections and Minority-Group Rep•·esenta

tion : A Re-Examination of Historical and Contemporary Evidence, Journal of Politics (Nov.

1981) (forthcoming) ; R. Engstrom and M. McDonald, The E lection of Blacks to City Coun

cils: Clarifying the Impact of Electoral Arrangements on the Seats/Population Relation

shii!J American Political •Science Review (June 1981); D. Taebel, Minority Representation

on u<ty Councils, 59 Social Science Quarterly 143- 52 (June 1978) ; T. Robinson and '1'. Dye,

Reformism and Black Representation on City Councils, 59 Social Science Quarterly 133-41

(June 1978) ; A. Karnig. Black Representati on on City Councils, 12 Urban Aft'airs Quarterly

223-43 (Dec. 1976) ; C. Jones, The Impact of Local Election Systems on Black Political Rep

resentation. 11 Urban Aft'airs Quarterly 345- 56 (March 1976).

'"U.S. , Con~:ress, House, Subcommittee No. 5 of the Committee on the Judiciary, Voting

Rights: Hearings on H .R . 6400. 89th Cong., 1s t sess .. 1965, pp. 123-311 ; U.S . Congress,

Senate Subcommittee on Constitutional Rights of the Committee on the Judi.c!ary, Amend

ments to the Voting Rights Act of 1965: Hearings on S. 818, S. 2456 . S. 25 07, and Title IV

of S. 2 02 9, 91st Cong., 1st and 2nd sess., 1969 and 1970, pp. 28-87, 396- 431, 661- 62; U.S.

Congress, House. Subcommittee on Civil and Constitutional Rights of the Committee on the

Judicia ry, Extension of the Voting Rights Act: Hearing on H.R. 939, H.R. 2148, H .R . 3247,

and H .R. 3501 , 94th Cong., "1st sess., 1975, pp. 17-60; U.S. Congress, Senate, Subcommittee

on Constitutional Rights of the Committee of the Judiciary, Extension of the Voting Rights

Act of 1965 : Hearings on S. 407, S. 903, S. 1297, S. 1409, and S. 1443.

19

Counties in Nebraska and New Mexico were successfully sued' for

attempting to dilute the Indian vote by instituting at-large election

voting schemes.H

Since 1975, the Department of ,Justice has issued approximately 85

letters of objection disapproving election changes in the State of Texas.

The proposed'changes found to be discriminatory included: redistrict

ing; majority vote requirements; numbered posts; polling place

changes and annexations. In the City of Victoria, Texas, population

over 50,000, Chicanos started to mobilize their political strength by

increasing voter turnout. Victoria has an at-large, numbered post, sys

tem with a majority rule requirement. Realizing that Chicanos were

gaining in strength, the city annexed numerous areas that were 85

percent Anglo. When the city tried to preclear the annexations, the

Attorney General issued a letter of objection. This forced the city to

adopt a mixed plan. For the first time ever, there is now a Chicano

on the city council. Minorities there believe that without the Voting

Ri-ghts Act, such representation would have been delayed indefinitely.

It is not uncommon for jurisdictions to resubmit, without revision,

changes to which obiections had previously been interposed. The town

council in Bishopville, South Carolina had been elected at-large with

non-sta~gered terms and a plurality vote requirement. Blacks con

stituted 49 percent of the population but prior to May 1975, no blacks

had been elected to the council. The town proposed a majority vote

requirement and staggered terms. Justice objected noting its objection

to a proposal for staggered terms made the previous year.

In 1968, the town of Hayneville, Alabama incorporated so that 85

percent of its electorate was white, in a county which in 1970 was 77

percent black. The boundaries of the town were in the shape of a cross,

at the corners of the cross were surrounding black populations which

were excluded from the incorporated township. The annexation was

not submitted unti11978. The Attorney General objected to the incor

poration and advised Haynevme it could comply with the Act by

expanding its boundaries to include the contiguous black neighbor

hoods whose resident<; desired to be in the town. The new boundaries,

incorporating the additional areas, were enacted by the legislature

in 1980. ·

Racial gerrymandering and malapnortionment have resulted in dis

tricts of variO'us shapes anrl sizes. In the 1880's the racially gerry

mandered 7th Cong-ressional District . of South Ca.rolina which was

one of the bJack districts in the State ·and included Charleston was

described in the New York Times as having the shape of a '"boa con

strictor." Distri·ct IV of the 1978 Warren County. Mississirmi redis

tricting plan was described as having a configuration resembling Ty

rannosaurus Rex.48

One Wisconsin town attempted to gerrymander Indians out of

!heir vo~ing district (in the tradition of Gomillion v. Lightfoot)

man active attempt to keep them from voting.49

. Some districts are grossly malapportioned. Seminole County, Geor

gia had elected its Commlission from the same voting district since

"U.S. v. Board of Superv!JHJrs of Thurston County. Nebraska., elvll Actron No. 79-0-380

(D. Neb. 1979) : U.S. v. San Juan County, Civil Action No. 79-507 JB (D.N.M . 1979).

'"Hearings, May 28th. Frank Parker.

•• U.S. v. Bartleme, Wisconsin, Civil Action No. 78-C-101 (E. 1) Wisconsin, 1978.

20

1933---one_of the districts, Donaldsonville, which is 40 perce;nt of the

county population and has the largest concentration of bla.cks, had

over 2,200 voters; Rock Pond had a voting district with 160 regis

tered voters. A suit was filed in 1980, claiming violations of the con

stitution. Under a consent decree the county was rea;pportioned into

5 new voting districts from which a bla;ck was elected from majority

bla;ck Donaldson ville.

Benign explanations may be offered for why these methods .have

been selected, but the results have been telling: minorities remain

severely underrepresented in county or state-wide positions.49a

Sect10n 5 is an integral complement to Federal court }litigation in a

number of jurisdictions. Nowhere is this more clear than Tarrant

County, Fort Worth. After multi-member state legislative districts

had been declared unconstitutional in the White v. Regester decision

(1973), a three-judge federal panel declared that multi-member state

legislative districts were constitutionally permissible in Tarrant

County and seven other populous Texas counties. In 1975, under court

order to adopt single member districts, the state legislature passed

J!ouse Bill1097, which was objected to in Tarrant and Nueces-Corpus

Christi Counties on the grounds that the districts were racially gerry

mandered.

FEDERAL EXAMINERS AND OBSERVERS

The Attorney General, as part of the Justice Department's efforts

to guarantee the right to vote under the fourteenth and fifteenth

.Amendments and the Voting Rights Act, has the power to send Fed

eral examiners and observers to jurisdictions covered by the Act, and

to any State or political subdivision where a court, at the urging of

the Attorney General or an aggrieved person, finds that such officers

are appropriate. In the ,former case, the appointment is not automatic.

Section 6 sets standards which the Attorney General must follow in

dete:rmining into which covered jurisdictions the ex•aminers will be

assigned. In the latter case, under Section 3 (a) of the Act, a Federal

court, in an interlocutory order or in a fina;l judgment, is the arbiter of

the need for such appointments. 5° In any case, examiners prepare lists

of voters whom State officia;ls are reqillred to register. ·

Under Section 8 of the Act, whenever Federal exa;miners are serv

ing in a particular area, the Attorney General may request that the

Office of Personnel Mana;gement assign one or more persons to observe

the conduct of an election. These Federal observers monitor the cast-

ing and counting of ballots. ·

During the earlier stages of the Voting Rights Act's life the use o£

examiners and observers was more prominent than is the case today.

In t]le last decade, •for instance, such officers were responsible for in

creasing minority registration by up to 27 percr.nt in some areas. 51 In

recent years, the Attorney Genera;} has assigned over 3,000 observers

to monitor suspect elections. 52 In making such assignments, the At-

••• Hearings, June 3rd. Abigail Turner Ibid., June 16th Raymond Brown.

"'As is true elsewhere In the Act, incidents that would n<>rmally require appointment

<>f examiners need n<>t require that result if such Incidents were unique and unlikely to re

occur. See Sectl<>n 3 (a).

61 See House Hearings, 1975, p. 171-172.

""See H<>use Hearings, 1981, Drew Days' testim<>ny, p. 9-10.

torney General has developed administrative criteri·u which mrist be

considered beforehand :

(1) The extent to which those who will run an election are

prepared so that there are sufficient voting hours and facilities,

procedural rules for voting are adequately publicized, and non

discriminatorily selected polling officials are instructed in elec

tion procedures;

(2) The confidence of the minority community in the electoral

process and the individuals conducting the election, including the

use of minorities as poll officials;

(3) The possibility of forces outside the official election machi

nery (such as rac~a,l violence, threats of violence, or a history of

discrimination in other areas) interfering with the election. 53

There is no evidence to suggest that this method of Federal inter

vention in election procedure has been anything but restrained, and

used sparingly in only the most essential situations. The Committee

would point out that these officials serve only when the situation

warrants. 54

While not used in the same numbers as in previous years, examiners

and observers were assigned to 500 elections in the covered jurisdic

tions in 1980.s.s In a separate development recently three counties not

subject to Section 4 coverage were designated as sites for federal

examiners.56 The Committee's hearings on H.R. 3112, if anything,

reflect the continuing existence of activity aimed at the intimidation

of racial and language minority persons seeking to register and vote. 5 7

Finally, with the onset of nationwide reapportionment, a process which

historically has led to actions impairing or diluting the voting rights

of racial and language minorities, any relaxation of federal protec

tions would be unwise. The Congress in 1975 specifically desired to

cover these practices during the current extension period to combat

this precise situation:58 . • •

Thus, based upon the record developed in its Subcommittee's hear

ings and the report of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, The Vot

ing Rights Act: Unfulfilled Goals, the Committee concludes that it

is essential to continue federal examiners and observers provisions of

the Act in full force and effect in order to safeguard the gains thus

far achieved in minority political participation, and to prevent future

infringements of Voting rights.

LANGUAGE AssiSTANCE

BACKGROUND

As indicated earlier, in 1975 Congress not only extended the time

period for the coverage of jurisdictions brought under Section 5 in

the original Act, but also expanded coverage of the Act to enforce

the 14th and 15th Amendments guarantees of language minority

citizens. Congress took this step (action) based on the extensive record

53 U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, supra, p. 22.

,. See Section 3(a) and Section 6 of the Voting Rights Act.

65 U.S. Commission on Civil Rights·, supra, p. 268-269.

50 U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, supra, p. 50-51.

57 See Committee Hearings, 1981.

58 See House Debates, 1975.

22

before it regarding voting and other discrimination · faced by such

citizens:

Testimony was received regarding inadequate numbers of

minority registration personnel, uncooperative registrars

(and) disproportionate effect of purging laws on non-English

speaking citizens because of language barrier ... (t)he exclu

sion of language minority citizens is further a~gravated by

acts of physical, economic, and political intimidation when

these citizens do attempt to exercise their franchise ... Memo

ries of past discourtesies or physical abuse may compound the

problems for many language-minority voters. The people in _

charge are frequently the same ones who so recently excluded

minorities from the political process ... The Subcommittee

(also) heard extensive testimony on the question of ... the

rules and procedures by which voting strength is translated

into political strength. The central problem is that of distribu

tion of the vote. 59

Furthermore, the Committee learned that :

Language minority citizens are also excluded from the' elec

toral process through the use of English-only elections. Of all

Spanish heritage citizens over 25 years old, for example, rriore

than 18:9 percent have failed to complete five years of school

compared to 5.5 percent for the total population. In Texas,

over 33 percent of the Mexican American population has not

completed the fifth grade.60

.. . ...

Tlie Committee found that the high illiteracy rates referred to are

"not the result of choice or mere happenstance; 61 they are the result.

of the failure to afford equal educational opportunities to members of

language minority groups. This point has repeatedly been highlighted

by the courts.62 · ·• _

As explained above, 63 Congress approached the range of problems

facing language minority citizens in a twofold manner: The Section 4

trigger was revised so that the more severe discriminatory practices

and procedures, which were similar in type and effect to those pro

hibited in the earlier covered jurisdictions, would be subject to Section

5 preclearance. The less severe, but equally troubling problems were

those resulting from high illiteracy levels of members of language

minority populations. To address these problems, Congress, in Section

203 of the 1975 Voting Rights Act, provided that language assistance

for such individuals be made available throughout the election

process.6•

The continuing existence of discriminatory practices and procedures

which are subject to Section 5 preclearance has been addressed else

where in this report addressed above. Other language assistance issues

are addressed below .

.. V<Yting Rights Extension, Report No. 94-196, House of Representatives (1975) here-

inafter referred to as the 1975 Committee Report, at pp. 16-18.

00 ld. p. 20.-.

61 ld .

.. Case citations here from 1975 Committee Report and Vilma Martinez's statement.

os See discussion in the General Statement portion of this Report .

.. .Jurisdictions who were covered by the Section 4 trigger in 197u also are required to

provide language assistance for language minority citizenso.

SEO'l'lON 203 OF THE AcT

Basis for Enactment

The Voting Rights Act, as enacted in 1965, recognized that literacy

teS'ts and other devices had been used to prevent 'blacks from registering

and voting; consequently, the use of such tests and devices was barred.

In the early 1970's a number of federal court decisions found that

English-only elections in areas with substantial non-English speaking

citizens operated as a test or device to keep citizens from voting.

In 1973, the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that:

If a person who cannot read English is entitled to oral

assistance, if a Negro is entitled to correction of erroneous

instructions, so a Spanish-speaking Puerto Rican is entitled

assistance in the language he can read or understand. [Puerto

Rican Organization for Political Action v. Kusper, 409 F. 2nd

575, 580 (7th Cir. 1973)]

In 1974, another New York federal court decision emphasized the

importance of offering bilingual assistance in order to guarantee the

right of Spanish-speaking Puerto Rican citizens to vote. The court

ruled that:

In ordet that the phrase "the right to vote" be more than an

empty platitude, a voter must be able effectively to register his

or her political choice. This involves more than physically

being able to pull a lever or marking a ballot. It is simply

fundamental that voting instructions and ballots, in addition

to any other material which forms part of the official commu

nication to registered voters prior to an election, must be in

Spanish as well as English, if the vote of Spanish-speaking

citizens is not to be seriously impaired. [Torres v. Sachs, 309

F. Supp. 309, S.D. New York July 25, 1974]

Even as early as 1923, the U.S. Supreme Court expressly recog

nized that citizens cannot be denied their fundamental rights because

of their lack of knowledge of the English language:

Certain fundamental rights [are guaranteed] to all those

who speak other languages as well as to those born with

English on the tongue. Perhaps it would be advantageous if

all had ready understanding of our ordinary speech, but this

cannot be coerced by methods which conflict with the Consti

tution-a desirable end cannot be promoted by prohibited

means.65

Furthermore, the U.S. Supreme Court in Gaston County v. United

States, 395 U.S. 285 (1969), recognized the inextricable relationship

between the denial of equal educational opportunities and voting- dis

crimination. The Supreme Court found that blacks who histoncally

had received inferior education were discriminatorily affected by the

use of literacy tests in voting even though such tests were no longer

administered in a discriminatory manner and progress had been made

in integrating the County's school system.66

65 Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U.S. 390, 401. .

06 See also Lassiter v. Northhampton Election Board; 36() U.S. 45 (1959).

Tp~:~se series of judic!al findings, together with the overwhelming

evidence presented in its 1975 hearmgs,"' led Congress to enact Section

203 of the Voting Rights Act (42 U.S.C.1973 aa-1).

A recent case reiterated the point made in (}aston Omtnty v. United

States, supra., that the vestiges of discrimination !).re not easily or

quickly eradicated:

While many of the overt forms of discrimination wreaked

upon Mexican Americans have been eliminated,the long his

tory of prejudice and deprivation remains a Significant ob

stacle to equal educational opportunity for these children.

The deep sense of inferiority, cultural Isolation, and accept

ance of failure, insti,lled in a people by generations of subJu

gation, cannot be eradicated merely by integrating the schools

and repealing the "No Spanish" statutes .... The severe educa

tional difficulties which Mexican American children in Texas

public schools continue to experience attest to the intensity

of those lingering effects of past discriminatory treatment.68

IMPLEMENTATION

When Congress enacted Section 203, it had as its goal assuring that

limited or non-English-speaking citizens 69 would receive the requisite

language assistance necessary to permit them to effectively exercise

thmr franchise. While enacted in part, in recognition of the long-term

effects of unequal educational oppor~unities received by such citizens,

the purpose of providing this assistance was not to encourage or dis

courage them from learning English. Language citizens disabled by

educational disparities, not of their making, to register and to vote

immediately.

Specifically, Section 203 requires that election, voter registration,

and other voting-Telated activities be conducted bilingually if (a)

more than 5 percent of the citizens of voting age in a jurisdiction are

members of specified language minority groups and (b) the illiteracy

rate of such persons, as a group, is higher than the national illiteracy

rate. Illiteracy is defined as failure to complete the fifth primary grade.

Coverage of this provision extends to political subdivisions in 30 dif

ferent states, primarily Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, California, Colo

rado, and Oklahoma.

When the U.S. Department of Justice issued its guidelines for the

implementation of this provision in 1976 and 1977 70 it correctly in

terpreted the mandate of Section 203 to be that election related ma

terials and assistance "be provided in a way designed to allow members

67 Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Civil and Constitutional Rights of the Judi·

ciary, House of Representatives, Ninety-Fourth Congress, First Session (1975)-herein

after referred to as the 1975 House Hearings.

os United States v. 7'ei1Jas, No. 5281 (E.D. Tex. Jan., 9, 1981) at pp. 66-67; (involved

bilingual education issues).

oo The Act, as amended in 197:>, provides for language assistance to "language minority"

citizens, defined (in 42 U.S.C. 1973 aa-'1) as persons of Spanish heritage, American

Indians, Asian Americans, and Alaskan Natives. The definition was determined on the

basis of the evidence of voting discrimination before the Congress in 1975. No evidence

regarding voting problems of other language groups was received. •In fact, Congress

examined the voter registration statistics for the 1972 Presidential election and found

that they showed a high degree of participation by other language groups : German,

79 percent; Italian, 77.5 percent; French, 72.7 percent; Polish, 79.8 percent; · and

Russian, 85.7 percent. This compared with voter participation for all Spanish ethnic

groups (Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, others) of 44.4 percent. See U.S. Bureau of the Census

chart on voter participation In the 1975 Committee Report at p. 23.

1o 28 CFR Part 55.

25

of applicable language minority groups to be effectively informed of

and pa1ticipate effectively in voting-connected activities.71 The Guide

lines explicitly state that compliance is best measured by the results

achieved. 72 They further note that a jurisdiction is more likely to

achieve compliance if it consults with language minority group mem

bers and their representatives.73 Both the Justice Department 74 and

Congress have suggested that an appropriate manner in which to com

ply with the letter and the spirit of .Section 203 is to focus the language

assistance so that only those language minority group members who

actually need such assistance, whether written and/ or oral, receive

them. This method of providing assistance is referred to as "targeting".

While the tone set by the Department of Justice Regulations on how

language assistance should be provided is laudatory, the assistance

which has been provided to covered jurisdictions has been found to be

less than vigorous. In 1978, the General Accounting Office (GAO)

reviewed the enforcement efforts of the Department in this regard. 75

It found that implementation of the minority language provisions

could be more effective i£, among other things, the Department clari

fied what constitutes an effective compliance approach and if they

provided more assistance to State and local officials.

More recent studies have also concluded that the Department of

Justice Guidelines have not provided adequate assistance to State and

local election officials who are responsible for implementing them,76

Absent more specific guidance from the Department, or any other

agency or organization, each affected county was left to devise its own

method of implementation.

In 1979, the Federal Elections Commission (FEC) conducted the

first comprehensive study to review the various methods used by cotm

ties to implement Section 203.77 The Commission found that the most

successful county programs, from both a cost and policy effectiveness

view, were those which greatly utilized the resources available in the

language minority communities for all facets of the registration and

election process. Unfortunately, of the administrators responding to

the FEC's questionnaire, 59 percent reported not having contacted

such organizations for any purpose. The Commission concluded that

local election administrators have exerted a limited effort to provide

comprehensive bilingual election services. They apparently have been

laboring under a widespread misconception:

Firstly, that just formalistically making bilingual services

available, without bringing them to the language minorities

through the links of community organizations, will produce

any great demand for them; and secondly, that the point of

the legislation is primarily to have bilingual forms available

and that the appropriate measure of its success, therefore, is

71Jd., Part 55.21b).

,. Id., Part 55.16.

73 ld.

"Id., Part 55.17 .

.,. Report of the Comptroller General of the United States-Voting Rights Act Enforce

ment Neens StrPngthening. Fehrnnr:v 6. 1 !l7R.

7• Bilingual Election Services Report, Vols. I, II, and III, l!'ederal Elections Commission

(1979) (hereinafter cited as FEC Report) and The Voting Rights Act: Unfulfilled Goals,

Report of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights (1981) (hereinafter cited as the 1981

Civil Rights Commission Report) .

77 FEC Report, supra.

H.Rept. 97-227 --- 4

26

the number of bilingual forms used. The goal of providing

bilingual election services is to facilitate the participation of

language minority citizens in the electoral process. Providing

bilingual printed materials is only one means toward this end.

(FEO R eport, Vol. III, at p. 58.)

The FEC Report further concluded that to assess the need for

language assistance, administrators should not rely solely on statis

tics such as the proportion of registered voters who are language

minority citizens or on the actual demand on election day for minority

language materials and/or oral assistance. This practice, according