Defendant's Response to Plaintiffs' Petition for a Permanent Injunction

Public Court Documents

May 19, 1982

5 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bolden v. Mobile Hardbacks and Appendices. Defendant's Response to Plaintiffs' Petition for a Permanent Injunction, 1982. 9d8463cc-cdcd-ef11-8ee9-6045bddb7cb0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/dad2334f-b1f4-4cc6-9101-a71eed669096/defendants-response-to-plaintiffs-petition-for-a-permanent-injunction. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

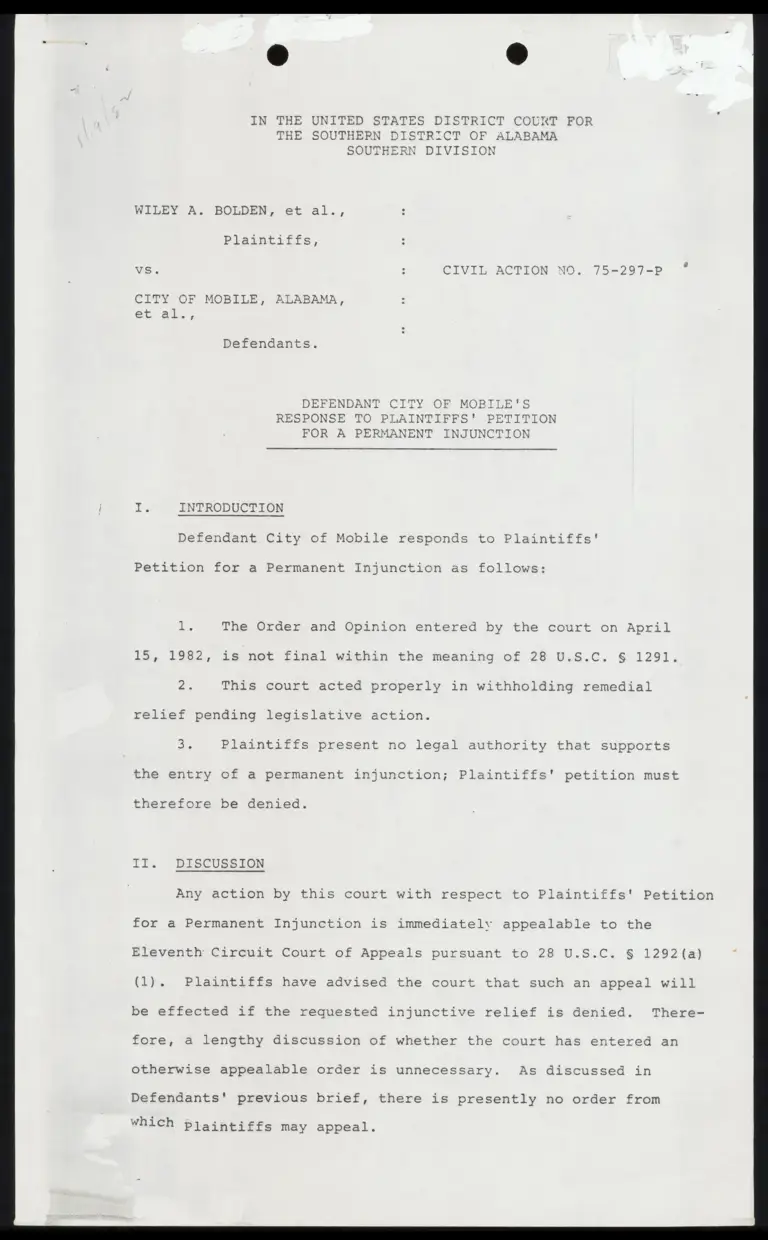

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR

THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

SOUTHERN DIVISION

WILEY A. BOLDEN, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

vs. : CIVIL ACTION NO. 75-297-P

CITY OF MOBILE, ALABAMA,

et al.,

Defendants.

DEFENDANT CITY OF MOBILE'S

RESPONSE TO PLAINTIFFS' PETITION

FOR A PERMANENT INJUNCTION

I. INTRODUCTION

Defendant City of Mobile responds to Plaintiffs’

Petition for a Permanent Injunction as follows:

: fF The Order and Opinion entered by the court on April

15, 1982, is not final within the meaning of 28 U.S.C. § 1291.

2. This court acted properly in withholding remedial

relief pending legislative action.

0 Plaintiffs present no legal authority that supports

the entry of a permanent injunction; Plaintiffs' petition must

therefore be denied.

Il. DISCUSSION

Any action by this court with respect to Plaintiffs' Petition

for a Permanent Injunction is immediately appealable to the

Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1292(a)

(1). Plaintiffs have advised the court that such an appeal will

be effected if the requested injunctive relief is denied. There-

fore, a lengthy discussion of whether the court has entered an

otherwise appealable order is unnecessary. As discussed in

Defendants' previous brief, there is presently no order from

which plaintiffs may appeal.

Plaintiffs’ reliance upon the Supreme Court's decision

in Gunn v. University Committee to End the War in Viet Nam™ is

misplaced. The Gunn opinion does not address the question

of finality and is wholly inapplicable to the instant “acts.

Plaintiffs accusingly maintain that the Fifth Circuit

to take notice" of Gunn when it rendered its decision in Garza

aD ; :

Vv. Smith. Defendant concedes that there is no reference to

Gunn in the Garza opinion. Indeed, any such reference would

be inappropriate because the cases are substantively and

procecdurally dissimilar. In Gunn defendants appealed directly

to the Supreme Court pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1253; the Court

dismissed the appeal for want of jurisdiction because "there

was no order of any kind either granting or denying an injunction

4 : ;

iy The Gunn district court had -- interlocutory or permanent.

concluded that defendants were "entitled" to injunctive relief,

: cosy 5 ;

but the "rather discursive per curiam opinion"~ failed to enter

such an order. The Supreme Court characterized the district

court's opinion in the following manner:

The complaint in this case asked for

an injunction "[r]estraining the

appropriate Defendants, their agents,

servants, employees and attorneys and

all others acting in concert with them

from the enforcement, operation or

execution of Article 474." 1Is that

the "injunctive relief" to which the

District Court thought the appellees

were "entitled"? If not, what less was

399 U.S. 383 (1970).

2 450 F.2d 790 (5th Cir. 1971).

3 28 U:S:C: § 1253 provides in pertinent part that ' 'any

party may appeal frofit an order granting or denying . . .

an interlocutory or permanent injunction . . . heard and

determined by & district court of three judges."

4 399 y.5. at 387:

5

I4.

to be enjoined, or what more? And against

whom was the injunction to run? Did the

District Court intend to enjoin enforcement

of all the provisions of the statute? Or

did the court intend to hold the statute

unconstitutional only as applied to speech,

including so-called symbolic speech? Or

was the court confining its attention tc

that part of the statute that prohibits

the use, in certain places and under

certain conditions, of "loud and vociferous

. « « language"? The answers to these

guestions simply cannot be divined with

any degree of assurance from the per curiam

opinion.

Plaintiffs, referring to Gunn, maintain as follows in

their Memorandum of Law:

The Supreme Court has explicitly

disapproved the procedure of withholding

an injunction against an unconstitutional

or unlawful state statute while inviting

the legislature to respond with 1ts own

remedy. . . . This is because "until a

district court issues an injunction, it

is simply not possible to know with any .

certainty what the court has decided. . . ."

The first statement is simply wrong. The Gunn Court held only

that a district court must actually enter or deny an injunction

before a section 1253 appeal is available. Similarly, Plaintiffs’

prefatory use of "This is because" in the second statement destroys

the intended meaning of the quoted language. In fact, the Gunn

court observed as follows:

One of the basic reasons for the

limit in" 28 u,5.C. § 1253 upon our

power of review is that until a

district court issues an injunction,

or enters an order denying one, it is

simply not possible to know with any

certainty what the court has decided =--

a state of affairs that is conspicuously

evident here.

Thus, Gunn has nothing to do with whether in some circumstances

a court should defer remedial relief pending possible

corrective action by the legislature.

® 14. at 388.

7 Plaintiffs' Memorandum of Law at 2 {citation to Gunn

anitted).

8

399 U.S. at 388 (emphasis added).

Plaintiffs' mischaracterization of the Gunn holding

reflects the general tenor of their Memorandum.’ This

court's qualified deferral to possible corrective action

by the Alabama legislature is proper. In the Supreme l_.urt's

consideration of Bolden Justice Blackmun concluded that

plaintiffs had proved purposeful discrimination, but concurred’

with the plurality's reversal of the case. Justice Blackmun

voted for reversal because this court's previous remedial relief

"was not commensurate with the sound exercise of judicial

10

discretion.” Furthermore, this court's action is entirely

r proper under the Supreme Court's 1978 decision in

Wise v. Lipscomb, which provides in pertinent part as follows:

The Court has repeatedly held

that redistricting and reapportioning

legislative bodies is a legislative task

which the federal courts should make every

effort not to pre-empt. . . When a federal

court declares an existing apportionment

scheme unconstitutional, it is therefore,

appropriate, whenever practicable, to afford

a reasonable opportunity for the legislature

to meet constitutional requirements by adopting

a substitute measure rather than for the

federal court to devise and order into effect

its own plan. The new legislative plan, if

forthcoming, will then be the governing law

unless it, too, is challenged and found to

violate the Constitution. "[A] State's

freedom of choice to devise substitutes

for an apportionment plan found uncon-

stitutional, either as a whole or in part,

? Plaintiffs state at pages 3 and 4 of their Memorandum that

the Fifth Circuit "directly implie{d] disapproval" of Garza when

it "refused" to follow Garza in United States v. Mississippi Power

& Light Co., 638 F.2d 899 (5th Cir. 1981). In fact, the Fifth

Circuit distinguished Mississippi Power fram Garza because of the

former's unusual procedural history. The Mississippi Power court

noted that "[o]Jur review of these orders does not raise the

usual problems attending piecemeal review because it can be

labeled 'piecemeal' only in a distorted sense of the word.”

Id. at 903. Contrary to the court's actions in Garza, the

Mississippi Power district court had fully decided every issue.

Rather than formally issuing the injunction, the Mississippi

Power district court had relied upon the declaratory force of its

on and the good faith of the parties to enforce the decree.

fth Circuit observed that " [t]he orders would be undeniably

ii. 1f the court had either granted or denied the injunctive

relief asked for. . . instead of retaining jurisdiction to

issue injunctions later if needed." Id. In contrast, the district

court here has not "fully decided every issue" since the issue of

the appropriate remedy remains open.

10 city of Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55, 80 (1980).

should not be restricte

commands of the Equal P

a

d

Certainly, at least as much deference 1s owed to corrective

legislative action providing for a form of government as for the

redrawing of legislative district lines.

III. CONCLUSION

Despite Plaintiffs' efforts to maintain otherwise, this

court has not entered a final order. Similarly, Plaintiffs

cannot seriously maintain that the court's adherence to Wise

is improper. It is clear that Plaintiffs are frustrated that

this court did not dismantle Mobile's existing form of government

in the Order and Opinion of April 32. This frustration

does not warrant the entry of ‘an immediate permanent injunction

contrary to the teachings of Belden and Wise.

Plaintiff's motion must be denied.

0, Go Dtontl

ARENDALL ’

W ai C. in dy y 111

RAYFORD L. ETHERTON, JR.

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I do hereby certify that I have served, on this {9 day

of Vhoae , , 1982, a copy of the foregoing pleading

on counsel of record for all parties to this proceeding by

depositing same in the United States mail, properly addressed

and first-class postage, prepaid.

11

437 U.S. 535, 539-40 (1978).