Brown Shoe Co. v. United States Court Opinion

Annotated Secondary Research

June 25, 1962

17 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Working Files. Brown Shoe Co. v. United States Court Opinion, 1962. 29f5e1b1-54e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/db29a418-6952-4860-a8cd-7e69e9081512/brown-shoe-co-v-united-states-court-opinion. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

K < ■ j

r •

. ■ ■. . -- ' ■■■ • .

■ * . . . . . .

. . . . . . . • ■ ' '

-V K igSpt g j f e i p ** : - w«-‘ ' - "■ < ' • ■ '<•*<*

.............. .......................... ............... — J

■ -*'

■ '•- ■ •

P

I

510 u. S. SUPREME COURT REPORTS 3 Led 2d

.. . : ■ .. ' • • ' ' !

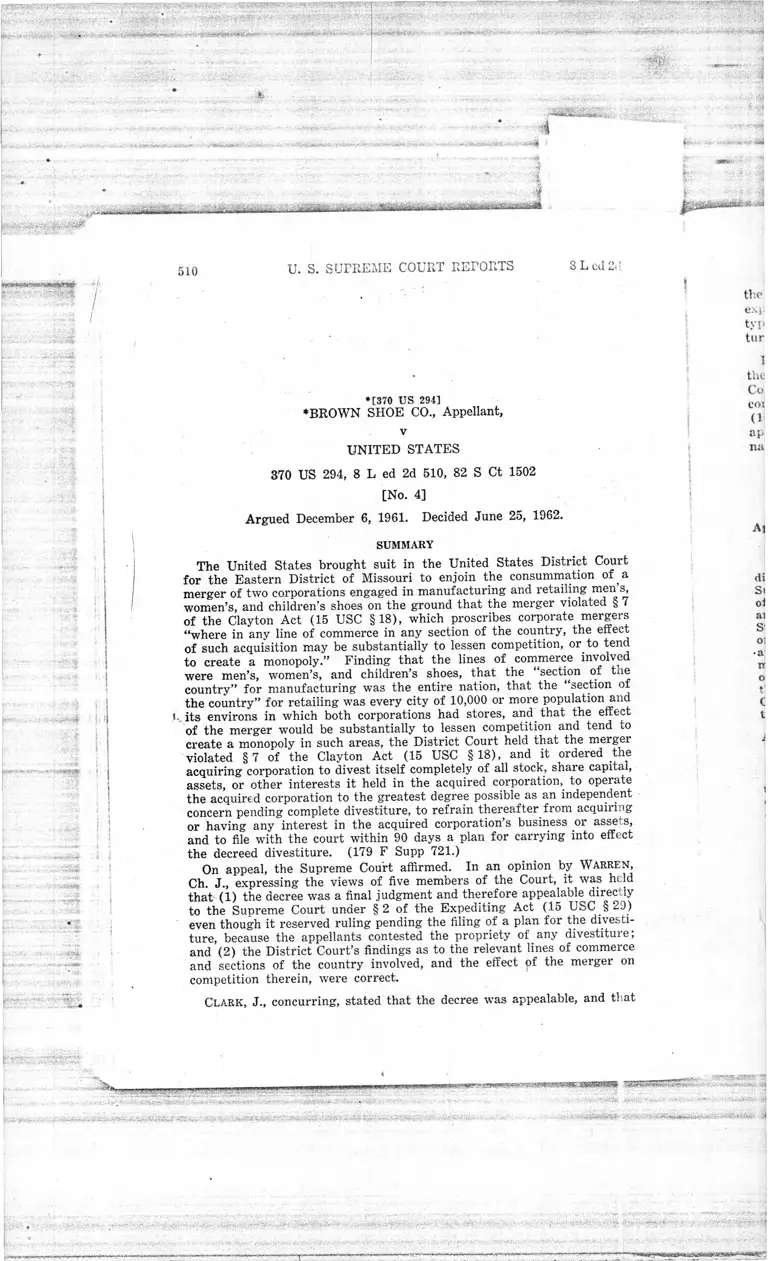

*[370 US 294]

♦BROWN SHOE CO., Appellant,

v

UNITED STATES

370 US 294, 8 L ed 2d 510, 82 S Ct 1502

[No. 4]

Argued December 6, 1961. Decided June 25, 1962.

SUMMARY

The United States brought suit in the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Missouri to enjoin the consummation of a

merger of two corporations engaged in manufacturing and retailing men s,

women’s, and children’s shoes on the ground that the merger violated § 7

of the Clayton Act (15 USC §18), which proscribes corporate mergers

“where in any line of commerce in any section of the country, the effect

of such acquisition may be substantially to lessen competition, or to tend

to create a monopoly.” Finding that the lines of commerce involved

were men’s, women’s, and children’s shoes, that the section of Lie

country” for manufacturing was the entire nation, that the “section of

the country” for retailing was every city of 10,000 or more population and

I. its environs in which both corporations had stores, and that the effect

of the merger wTould be substantially to lessen competition and tend to

create a monopoly in such areas, the District Court held that the merger

violated §7 of the Clayton Act (15 USC §18), and it ordered the

acquiring corporation to divest itself completely of all stock, share capital,

assets, or other interests it held in the acquired corporation, to operate

the acquired corporation to the greatest degree possible as an independent

concern pending complete divestiture, to refrain thereafter from acquiring

or having any interest in the acquired corporation’s business or assets,

and to file with the court within 90 days a plan for carrying into effect

the decreed divestiture. (179 F Supp 721.)

On appeal, the Supreme Court affirmed. In an opinion by WARREN,

Ch. J., expressing the views of five members of the Court, it was held

that (1) the decree was a final judgment and therefore appealable directly

to the Supreme Court under § 2 of the Expediting Act (15 USC § 29)

even though it reserved ruling pending the filing of a plan for the divesti

ture, because the appellants contested the propriety of any divestitui e ,

and (2) the District Court’s findings as to the relevant lines of commerce

and sections of the country involved, and the effect pf the merger on

competition therein, were correct.

C l a r k , J., concurring, stated that the decree was appealable, and that

*

- ■ ■ ' ' ' - - ■ i ■ ■ ■ ; • • ' ' - ■ • • .. L.-. . . .. . •. -

: ■ • ...................|.................. ...........

*

- ■

. . _. . . •• . . - • • ' . ■ - . ■ • • X ■ : ' . ■ * ■ *

.... ............................ ........ .............*— ----htWi. kw.'..-*-*-* - ......

-■■ . ... ■ ■ -—»

. . . . . *_. v.

.11BROWN SHOE CO. v UNITED STATES

370 US 294, S L ed 2d 510, 82 S Ct 1502

« * «expressed the view tl a ( . f th country” for both manufac-

tvnes and that the relevant section ot tne country iu

taring and retailing was the entire nation.

tj * pr a xt T dissenting in part and concurring in part, stated that

thf a ^ ’sho'uld be dismissed for lack of jurisdiction because the District

rourt’s decree was not final, but that if the merits of the case were to be

fonsidered the merger should be held to violate § 7 of the Clayton Act

t S i m although the relevant “line of commerce” was the weMiiw-

relevant "section of the country” was the

nation as a whole.

Frankfurter and White, JJ., did not participate.

HEADNOTES

Classified to U. S. Supreme Court Digest, Annotated

Appeal and Error §§ 31, 32.3 — from

District Court — finality — anti

trust suit.

1. U n d e r 15 USC § 29, p ro v id in g fo r

d ire c t a p p e a ls to th e U n ite d S ta te s

S u p rem e C o u rt fro m fina l ju d g m e n ts

of F e d e ra l D is tr ic t C o u rts in c iv il

a n t i t r u s t s u its in w h ich th e U n ite d

S ta te s is th e c o m p la in an t, th e r ig h t

o f rev iew in su c h ca se s is lim ite d to

ap p e a ls f ro m d ec rees d isp o s in g o f a ll

m a tte rs , a n d th e re is no p o ss ib ility

of a n a p p e a l in su ch ca se s e i th e r to

th e S u p rem e C o u rt o r to a F e d e ra l

C o u rt o f A p p ea ls f ro m a n in te r lo c u

to ry decree .

d ic tio n is a th re sh o ld in q u iry ap p ro

p r ia te to th e d isp o s itio n o f every case

t h a t com es b e fo re th e C ourt.

’

Appeal and Error § 24

federal rule.

4. T he' re q u ire m e n t th a t a final

ju d g m e n t sh a ll h av e been e n te re d in

a ca se by a lo w er c o u r t b e fo re a r ig h t

o f ap p e a l a t ta c h e s h a s rem a in ed , w ith

o ccas io n a l m od ifications, a c o rn e i-

s to n e of th e s t r u c tu re of ap p e a ls m

th e fe d e ra l c o u rts .

finality —

Appeal and Error § 4; Supreme Court

of the United States § 10 — juris

diction by consent.

2. T h e m e re c o n se n t o f th e p a r t ie s

to th e U n ite d S ta te s S u p rem e C o u rt’s

c o n s id e ra tio n a n d d ec is ion of a ca se

c a n n o t, by its e lf , co n fe r ju r is d ic t io n

on th e c o u rt.

Court of the

— inquiry into

Courts §14; Supreme

United States § 1 •

jurisdiction.

3. A rev iew of th e so u rce s o f th e

U n ite d S ta te s S u p rem e C o u rt’s ju r is -

A ppea l an d E r r o r § 23 — f in a lity —

c r ite r io n .

5. T h e U n ite d S ta te s S u p rem e C o u rt

h a s a d o p ted e s se n tia lly p ra c tic a l te s ts

fo r id e n tify in g th o se ju d g m e n ts w h ich

a re , a n d th o se w h ich a re n o t, to be

c o n s id e red “ final,” a p ra g m a tic a p

p ro a c h to th e q u es tio n of w h a t is a

final ju d g m e n t b e in g e s se n tia l to th e

ac h ie v em e n t o f th e ju s t , speedy , an d

in ex p en siv e d e te rm in a tio n o f every a c

tio n , w h ich is th e to u c h s to n e of fe d

e ra l p ro ce d u re .

Courts §§ 16, 774 — jurisdiction —

previous exercise.

6. W hile th e U n ite d S ta te s S up rem e

C o u rt is n o t bou n d by p re v io u s 'e x e r -

ANNOTATION REFERENCES

1. Validity, under § 3 of the Clayton Act

(15 USC §14), of contract by purchaser

of goods to take his entire requirem ents

from the seller. 5 U ed 2d 1105.

2. Contract by one party to sell his en

tire output to, or to take his entire re

quirem ents of a commodity from , the other

p arty as contrary to public policy or an ti

monopoly sta tu te . 83 ALR 11<3»

-V- v . - ***** V f A ’-V w. .TVV 4 . - : . ' . ~ - ; ■

k

«♦ »» ........

,11

! i

H

4

i I f . . *i * .

i ?

* i

J

i

- . - ... . , ... -V-.

I

. M

BROWN SHOE CO. v UNITED STATES

370 US 294, 8 L ed 2d 510, 82 S Ct 1502

OPINION OF THE COURT

*[370 US 296]

*Mr. Chief Justice Warren deliv

ered the opinion of the Court.

assets be kept separately identifia

ble. The merger was then effected

on May 1, 1956.

I.

This suit was initiated in Novem

ber 1955 when the Government filed

. a civil action in the United States

District Court for the Eastern Dis

trict of Missouri alleging that a con

templated merger between the G. R.

Kinney Company, Inc. (Kinney),

and the Brown Shoe Company, Inc.

(Brown), through an exchange of

Kinney for Brown stock, would vio

late § 7 of the Clayton Act, 15 USC

§18. The Act, as amended, pro

vides in pertinent part:

“No corporation engaged in com

merce shall acquire, directly or in

directly, the whole or an]'’ part of

the stock or other share capital . . .

of another corporation engaged also

in commerce, where in ary line of

commerce in any section of the coun

try, the effect of such acquisition

may be substantially to lessen com

petition, or to tend to create a

monopoly.”

The complaint sought injunctive

relief under § 15 of the Clayton Act,

15 USC § 25, to restrain consumma

tion of the merger.

A motion by the Government for

a preliminary injunction pendente

lite was denied, and the companies

were permitted to merge provided,

however, that their businesses be

operated separately and tnat their

1. Of these over 1,230 outlets under

Brown’s control a t the tim e of the filing

of the complaint, Brown owned and oper

ated over 470, while over 570 were inde

pendently owned stores operating under

the Brown “Franchise Program ’ and over

190 were independently owned outlets

operating under the “Wohl P lan.” A store

operating under the Franchise Program

agrees not to carry competing lines of

*[370 US 297]

*In the District Court, the Govern

ment contended that the effect of

the merger of Brown—the third

largest seller of shoes by dollar vol

ume in the United States, a leading

manufacturer of men’s, women’s,

and children’s shoes, and a retailer

with over 1,230 owned, operated or

controlled retail outlets1—and Kin

ney—the eighth largest company,

by dollar yolume, among those pri

marily engaged in selling shoes, it

self a larke manufacturer of shoes,

;and a retailer with over 350 retail

outlets—“may be substantially to

lessen competition or to tend to

create a monopoly” by eliminating

actual or potential competition in the

production of shoes for the national

wholesale shoe market and in the

sale of shoes at retail in the Nation,

by foreclosing competition from “a

market represented by Kinney’s re

tail outlets whose annual sales ex

ceed $42,000,000,” and by enhancing

Brown’s competitive advantage over

other producers, distributors and

sellers of shoes. The Government

argued that the “line of commerce”

affected by this merger is “foot

wear,” or alternatively, that the

“line[s]” are “men’s,” “women’s,”

and “children’s” shoes, separately

considered, and that the “section of

the country,” within which the anti

competitive effect of the merger is

to be judged, is the Nation as a

shoes of other m anufacturers in re tu rn for

certain aid from Brown; a store under the

Wohl P lan sim ilarly agrees to concentrate

its purchases on lines which Brown sells

through Wohl in return for credit and

merchandising aid. See note 66, infra . In

addition, Brown shoes were sold through

numerous reta ilers operating entirely in

dependently of Brown.

nrx u\:

, •• -W!-.,-; -«*******•» •« • •

■ •

Is

1 i:

■ --- 4

I;

.... *4

if

l

. ...»---- ,

. ■ . • * .1

- —— - - ' ----------- > -»|

■' -■ ** ■ 4|

d - . f - • - - ■'-•4'■ s ■ - • ■ • ■ • -• •

, jsgwrjjs-v tf. fw. f t *&>■*>•

• I I K ; . : ' , :

. ---- 4

• •

.-. ■ ■■ '•- • • ■- ' UV.iK *£>/. / ••» f

& ■ • • . • •.........

vr-.fcV-*. &i

.................... -- , ■ - • ■ • • • ~4

■ - ••• - ■ - ft - • • -- £ ••- •■■■ t #4 • - ■ “ ' -•* • 7 'V5U* '

.•' '-SWV '■ - ■'■ ■ - ■ ■ ■ ■

.. —

\hiniy, '• :r%' ’

Pc*m?i8sw»Si!w

i

. . . ■ «

( - r-'4 . f

■. . ,.

̂.4 ̂.V ■' 5

:

.: . ■ 1

r "-:

“- s i 8

Ijffgl

520 U. S. SUPREME COURT REPORTS 8 L ed ‘V

whole, or alternatively, each sepa-

* [370 US 298]

rate city or city and its immediate

surrounding area in which the par

ties sell shoes at retail.

In the District Court, Brown con

tended that the merger would be

shown not to endanger competition

if the “line[s] of commerce” and

the “section [s] of the country” tvere

properly determined. Brown urged

that not only were the age and sex

of the intended customers to be con

sidered in determining the relevant

line of commerce, but that differ

ences in grade of material, quality

of workmanship, price, and customer s

use of shoes resulted in establishing;

different lines of commerce. While

agreeing with the Government that,

with regard to manufacturing, the

relevant geographic market for as

sessing the effect of the merger updn

competition is the country as / a

whole, Brown contended that with

regard to retailing, the market must

vary with economic reality from the

central business district of a large

city to a “standard metropolitan

area”2 for a smaller community.

Brown further contended that, both

‘ at the manufacturing level and at

the retail level, the shoe industry

enjoyed healthy competition and

that the vigor of this competition

would not, in any event, be dimin

ished by the proposed merger be

cause Kinney manufactured less

than 0.5% and retailed less than

2% of the Nation’s shoes.

The District Court rejected the

broadest contentions of both parties.

The District Court found that “there

is one group of classifications which

2. “The general concept adopted in de

fining a standard m etropolitan area [is]

th a t of an in tegrated economic area with

a large volume of daily travel and commu

nication between a central city of 50,000

inhabitants or more and the outlying parts

of the area. . , , Each area (except in

*[370 US 299]

is understood and recognized *by the

entire industry and the public—the

classification into ‘men’s,’ ‘women’s’

and ‘children’s’ shoes separately and

independently.” On the other hand,

“ [t] o classify shoes as a whole could

be unfair and unjust; to classify

them further would be impractical,

unwarranted and unrealistic.”

Realizing that “the areas of effec

tive competition for retailing pur

poses cannot be fixed with mathe

matical precision,” the District

Court found that “when determined

by economic reality, for retailing, a

‘section of the country’ is a city of

10,000 or more population and its

immediate and contiguous surround

ing area, regardless of name desig

nation, and in which a Kinney store

and a Brown (operated, franchise,

or plan) [3] store are located.”

The District Court rejected the

Government’s contention that the

combining of the manufacturing fa

cilities of Brown and Kinney would

substantially lessen competition in

the production of men’s, women’s, or

children’s shoes for the national

wholesale market. However, the

District Court did find that the like

ly foreclosure of other manufactur

ers from the market represented by

Kinney’s retail outlets may substan

tially lessen competition in the man

ufacturers’ distribution of “men’s,”

“women’s,” and “children’s” shoes,

considered separately, throughout

the Nation. The District Court also

found that the merger may substan

tially lessen competition in retail

ing alone in “men’s,” “women’s,” and

“children’s” shoes, considered sepa-

New England) consists of one or more

entire counties. In New England, m etro

politan areas have been defined on a town

basis ra th e r than a county basis.” II US

Bureau of the Census, United S tates Cen

sus of Business: 1954, p. 3.

3. See note 1, supra.

?!*?**! T

r.**'A t

f

BROWN SHOE CO.

370 US 294, 8 L ed

rately, in every city of 10,000 or

more population and its immediate

surrounding area in which both a

Kinney and a Brown store are lo

cated.

Brown’s contentions here differ

only slightly from those made be

fore the District Court. In order

fully to understand and appraise

these assertions, it is necessary to

*[370 US 300]

set *out in some detail the District

Court’s findings concerning the na

ture of the shoe industry and the

place of Brown and Kinney within

that industry.

The Industry. y

The District Court found that al

though domestic shoe production

was scattered among a large num

ber of manufacturers, a small num

ber of large companies occupied a

commanding position. Thus, while

24 largest manufacturers produced

about 35% of the Nation’s shoes,

the top 4—International, Endicott-

Johnson, Brown (including Kinney)

and General Shoe—alone produced

approximately 23% of the Nation’s

shoes or 65% of the production of

the top 24.

In 1955, domestic production of

nonrubber shoes was 509.2 million

pairs, of which about 103.6 million

pairs were men’s shoes, about 271

million pairs were women’s shoes,

and about 134.6 million pairs were

children’s shoes.4 5 The District

Court found that men’s, women’s,

4. US Bureau of Census, F acts fo r In

dustry, Production, by Kind of Footwear:

1956 and 1955, Table 1, Production Series

M31A-06, introduced as D efendant’s Ex

h ib it MM. The term “nonrubber shoes”

includes leather shoes, sandals and play

shoes, but excludes canvas-upper, rubber-

soled shoes, athletic shoes and slippers.

Ibid.

5. These figures are based on the 1954

Census of Business. For th a t enum era

tion, the Census Bureau classification

v UNITED STATES 521

2d 510, 82 S Ct 1502

and children’s shoes are normally

produced in separate factories.

The public buys these shoes

through about 70,000 retail outlets,

only 22,000 of which, however, de

rive 50% or more of their gross re

ceipts from the sale of shoes and are

classified as “shoe stores” by the

*[370 US 301]

Census Bureau.6 These *22,000 shoe

stores were found generally to sell

(1) men’s shoes only, (2) women’s

shoes only, (3) women’s and chil

dren’s shoes, or (4) men’s, women’s,

and children’s shoes.

. The District Court found a “defi

nite trend” among shoe manufac

turers to acquire retail outlets. For

example, International Shoe Com

pany had no retail outlets in 1945,

but by 1956 had acquired 130; Gen

eral Shoe Company had only 80 re

tail outlets in 1945 but had 526 by

1956; Shoe Corporation of America,

in the same period, increased its re

tail holdings from 301 to 842; Mel

ville Shoe Company from 536 to 947;

and Endicott-Johnson from 488 to

540. Brown, itself, with no retail

outlets of its own prior to 1951, had

acquired 845 such outlets by 1956.

Moreover, between 1950 and 1956

nine independent shoe store chains,

operating 1,114 retail shoe stores,

were found to have become subsidi

aries of these large firms and to have

ceased their independent operations.

And once the manufacturers ac

quired retail outlets, the District

Court found there was a “definite

“shoe stores” included separately onerated

leased shoe departm ents of general stores,

as distinguished from the shoe depart

m ents of general stores operated only as

sections of the la tte r’s general business.

US Bureau of Census, Retail Trade, Single

U nits and M ultiunits, BC58-RS3, p. I.

As described, infra, Brown operated nu

merous leased shoe departm ents in gen

eral stores which would be included in the

Census B ureau’s to ta l of “shoe stores.”

------- :

1 *r--------------------. . . . . ••• u •>- t

------------ • - • - V. '■ • • ">• •

4

v* . - ■

BROWN SHOE CO.

, 370 US 294, 8 L ed

about 1% of the national pairage

sales of men’s shoes; approximately

4.2 million pairs were of women’s

shoes or about 1.5% of the national

pairage sales of women’s shoes; and

approximately 2.7 million pairs

were of children’s shoes or about

2% of the national pairage sales of

children’s shoes.7

In addition to this extensive re

tail activity, Kinney owned and

operated four plants which manu

factured men’s, women’s, and chil

dren’s shoes and whose combined

output was 0.5 % of the national

shoe production in 1955, making

Kinney the twelfth largest shoe

manufacturer in the United States.

Kinney stores were found to ob

tain about 20% of their shoes from

Kinney’s own manufacturing plants.

At the time of the merger, Kinney

*[370 US 304]

bought no shoes from Brown; *how-

ever, in line with Brown’s conceded

reasons8 for acquiring Kinney,

Brown had, by 1957, become the

largest outside supplier of Kinney’s

shoes, supplying 7.9% of all Kin

ney’s needs.

It is in this setting that the merger

was considered and held to violate

§ 7 of the Clayton Act. The District

Court ordered Brown to divest itself

completely of all stock, share capital,

7. Kinney’s pairage sales of m en’s,

women’s, and children’s shoes were ex

tracted from exhibits submitted to the

Government in response to its in terroga

tories. See GX 6, R 4853. These s ta tis

tics are virtually identical to those cited in

appellant’s brief, w ith but one exception.

In its in ternal operations, appellant classi

fies certain shoes as “ growing g irls’ ”

shoes while the cited figures follow the

Census B ureau’s trea tm en t of such shoes

as “women’s” shoes.

8. As sta ted in the testim ony of Clark

R. Gamble, P resident of Brown Shoe Com

pany:

“It was our feeling, in addition to

v UNITED STATES 523

2d 510, 82 S Ct 1502

assets or other interests it held in

Kinney, to operate Kinney to the

greatest degree possible as an in

dependent concern pending complete

divestiture, to refrain thereafter

from acquiring or having any in

terest in Kinney’s business or assets,

and to file with the court within 90

days a plan for carrying into effect

the divestiture decreed. The Dis

trict Court also stated it would re

tain jurisdiction over the cause to

enable the parties to apply for such

further relief as might be necessary

to enforce and apply the judgment.

Prior to its submission of a divesti

ture plan, Brown filed a notice of

appeal in the District Court. It

then filed a jurisdictional statement

in this Court, seeking review of the

judgment below as entered.

II.

Jurisdiction.

Appellant’s jurisdictional state

ment cites as the basis of our juris

diction over this appeal § 2 of the

*[370 US 305]

Expediting *Act of February 11,

1903, 32 Stat 823, as amended, 15

USC § 29. In a civil antitrust action

in which the United States is the

complainant that Act provides for

a direct appeal to this Court from

“the final judgment of the district

getting a distribution into the field of

prices which we were not covering, it was

also the feeling th a t as Kinney moved into

the shopping centers in these free standing

stores, they were going into a higher in

come neighborhood and they would prob

ably find the necessity of up-grading and

adding additional lines to their very suc

cessful operation th a t they had been doing

and it would give us an opportunity we

hoped to be able to sell them in th a t cate

gory. Besides tha t, it was a very success

ful operation and would give us a good

diversified investm ent to stabilize our

earnings.” T 1323.

I

1'

:&

; !j. .1 •

V v ? .T ^ v 6T r- T 'r w-'’' v- \ ’v ; , - ; ' jW!? t7 T r " —*-"■) “” :

: .y, ■ ’ - .■ ■ --?<

-- — i.... .. ' > ■■■. .-. •.••■.?• ■ : . • ; ■ 5;. W ^ V . ' . "

9 ■ — ja »: -.1-. H rk l. ,

. . .

.... .

i ' -...-it-,,,. «-.• *

i

h

■. ■ I**'’* -

4 L

•**./ ̂ Vrt. * “ < -C' ’• M «K* *'*' ̂ j

-1

a

». j 4̂

-aSK̂K :;. >■• /

.*' V

g;ff# :f|:

: . 5 ■ j

, i

*i':

. i i

524 U. S. SUPREME COURT REPORTS 8 L ed 2d

court.”9 (Emphasis supplied.) The

Government does not contest ap

pellant’s claim of jurisdiction; on

the contrary, it moved to have the

judgment below summarily affirmed,

conceding our present jurisdiction

to review the merits of that judg

ment. We deferred ruling on the

Government’s motion for summary

affirmance and noted probable juris

diction over the appeal. 368 US

825, 4 L ed 2d 1521, 80 S Ct 1595.10

It was suggested from the bench

during the oral argument that, since

the judgment of the District Court

does not include a specific plan for

the dissolution of the Brown-Kinney

merger, but reserves such a ruling

pending the filing of suggested plans

for implementing divestiture, the

judgment below is not “final” as

contemplated by the Expediting Act.

In response to that suggestion, both

parties have filed briefs contending

that we do have jurisdiction to dis

pose of the case on the merits in its

present , posture. However, the

mere consent of the

H eadno te 2 parties to the Court’s

consideration and deci

sion of the case cannot, by itself,

confer jurisdiction on the Court.

See American Fire & Casualty Co.

v Finn, 341 US 6, 17, 18, 95 L ed

‘702, 710, 71 3 Ct 534, 19 ALR2d

738; People’s Bank v Calhoun

(People’s Bank v Winslow), 102

US 256, 260, 261, 26 L ed 101, 102;

Capron v Van Noorden (US) 2

Crunch 126, 127, 2 L ed 229. There

fore, a review of the

sources of the Court’s

Iiead n o te 3 j m-isdietion is a thresh-

*[370 US 306]

old * inquiry appropriate to the dis

position of every case that comes

before us. Revised Rules of the

Supreme Court, 15(1) (b), 23(1)

(b) • Kesler v Department of Public

Safety, 369 US 153, 7 L ed 2d 641,

82 S Ct 807; Collins v Miller, 252

US 364, 64 L ed 616, 40 S Ct 347;

United States v More (US) 3

Crunch 159, 2 L ed 397.

The requirement that a final

judgment shall have been entered in

/a case by a lower court before a

/right of appeal attaches has an

/ ancient history in federal practice,

first appearing in the

H eadno te 4 Judiciary Act of 1789.11

H eadno te 5 With occasional modi

fications, the require

ment has remained a cornerstone of

the structure of appeals in the

federal courts.12 The Court has

adopted essentially practical tests

for identifying those judgments

which are, and those which are not,

to be considered “final.” See, e. g.,

Cobbledick v United States, 309 US

323, 326, 84 L ed 783, 785, 60 S Ct

540; Market Street R. Co. v Rail

road Com. 324 US 548, 552, 89 L ed

1171, 1177, 65 S Ct 770; Republic

Natural Gas Co. v Oklahoma, 334

US 62, 69, 92 L ed 1212, 1220, 68

S Ct 972; Cohen v Beneficial In

dustrial Loan Corp., 337 US 541,

546, 93 L ed 1528, 1536, 69 S Ct

9. Congress thus lim ited the rig h t of

review in such cases to an appeal from a

decree which disposed of all

H eadno te 1 m atters, and it precluded the

possibility of an appeal either

to th is Court or to a Court of Appeals

from an interlocutory decree. United

S tates v California Co-op. Canneries, 279

US 553, 558, 73 L ed 838, 842, 49 S Ct 423.

10. A fter prooable jurisdiction had been

noted, a joint motion of the parties to

postpone oral argum ent or. the appeal to

the present Term of the Court was g ran t

ed. 365 US 825, 81 S Ct 711.

11. Section 22, 1 S ta t 84, in its present

:orm, 28 USC § 1291.

12. Cf. 28 USC § 1292; Fed Rules Civ

?roc 54(b); 28 USC §1651; Ex parte

United S tates, 220 US 420, 57 L ed 281,

33 S Ct 170; United S tates v United States

Dist. Court, 334 US 258, 92 L ed 1351, 68

3 Ct 1035; Beacon Theatres, Inc. v W est

e r 359 US 500, 3 L ed 2d 988, 79 S Ut

943,

i

1221; D i

US 121. 1

620, 82 S

Com. v

ulator i

245, 25o

v F . 5 ’L

US 2211 ,

S Ct 6 f

matic •1 T

finalitv• 1

to the

speedy

tion o.f

stones 0

In lTt<

pediting

basis o:

the ispu

raised <

or the C

have Pi

whiclii

conside

they 1IY<

to prec

ComeKt.

Inc. \ r I

L ed 6(

Chaiia '

13. Fi

14. S<

Co. 2;26

& Ju dg

Cases, 1

576-5■77

64 I, ec

v Baltic

535 (LX

332 1U- v"

United

Co. 83

[releva

a t 341

1208 7

L ed 1

United

295,

521. r

Statk ■?

lleidai

TTffW-:

te«ssis;5»:̂ 'V'-'-̂ ,!,-!- '•>' -. f»!

; , :. . I | . • ;-'■ '• .- ; ■■' ■■ .■ .......... . - ' •' ■ ' ' ■ ■'■ 1 ■ ' ■ A' . ~:

x:',* *r itwS'W

fe^AfeSA -

a I

til

a

R

<\

se

sg

nM

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

^ .V-. v-- - - . ...v , v ..,v:.:,-. ,. • ; . - A ;

*M BROWN SHOE CO.

370 US 294, 8 L < d

>•’•'1 ; Di Bella v United States, 369

US 121, 124, 129, 7 L ed 2d 614, 617,

f*

h-

620, 82 S Ct 654; cf. Federal Trade

Com. v Minneapolis-Honeywell Reg

ulator Co. 344 US 206, 212, 97 L ed

is- 245, 252, 73 S Ct 227; United States

«‘S v F. M. Schaefer Brewing Co. 356

iif US 227, 232, 2 L ed 2d 721, 725, 78

n S Ct 674, 73 ALR2d 235. A prag: * ■ llC matic approach to the question of

!, finality has been considered essential

jit . to the achievement of the “just,

speedy, and inexpensive determina

tion of every action” :13 the touch

stones of federal procedure.

Tn most cases in which the Ex-

neHiting_ Ac.t,Jias been cited "Sinne"

________

the issue of “finality” has not been

■ UNITED STATES 525

d 510, 82 S Ct 1502

334 US 110, 92 L ed 1245, 68 S Ct

947. The question has generally

been passed over without comment

in adjudications on the

H ead n ote 6 merits. While we are

not bound by previous

exercises of jurisdiction in cases in

which our power to act was not

questioned but was passed sub silen-

tio, United States v L. A. Tucker

Truck Lines, Inc. 344 US 33, 38, 97

L ed 54, 73 S Ct 67; United States

ex rel. Arant v Lane, 245 US 166,

170, 62 L ed 223, 224, 38 S Ct 94,

neither should we disregard the im

plications of an exercise of judicial

authority assumed to be proper for

over 40 years.14 Cf. Stainback v

*[370 US 3081

Mo *Hock Ke Lok Po, 336 US 368,

raised or discussed by the parties 379, 380, 93 L ed 741, 749, 750, 69

o**the Court. On but few occasions

*[370 US 307]

have particular ^orders in suits to

which that Act is applicable been

considered in the light of claims that

they were insufficiently “final” so as

to preclude appeal to this Court.

Compare Schine Chain Theatres,

Inc. v United States, 329 US 686, 91

L ed 602, 67 S Ct 367, with Schine

Chain Theatres, Inc. v United States,

S Ct 606; Radio Station WOW v

Johnson, 326 US 120, 125, 126, 89

L ed 2092, 2097-2099, 65 S Ct 1475.

We think the decree of the Dis

trict Court in this case had sufficient

indicia of finality for us

H ead n ote 8 to hold that the judg

ment is properly appeal

able at this time. We note, first,

that the District Court disposed of

13. Fed Rules Civ Proc 1.

14. See, e. g., United S tates v Reading

Co. 226 F 229, 286 (DC ED P a), 1 Decrees

& Judgm ents in Civil Federal A n titru st

Cases (hereinafter cited “D & J ” ) 575,

576-577, affd in pertinent part, 253 US 26,

64 L ed 760, 40 S Ct 425; United S tates

v N ational Lead Co. 63 F Supp 513, 534,

535 (DC SD NY), 4 D & J 2846, 2851, affd

332 US 319, 91 L ed 2077, 67 S Ct 634;

United S tates v Timken Roller Bearing

Co. 83 F Supp 284, 318 (DC ND Ohio)

[relevant portions of the decree reprinted

a t 341 US 593, 602 note 1, 95 L ed 1199,

1208, 71 S Ct 971], mod 341 US 593, 95

L ed 1199, 71 S Ct 971; United S tates v

United Shoe Machinery Corp. 110 F Supp

295, 352-354 (DC D M ass), affd 347 US

521, 98 L ed 910, 74 S Ct 699; United

States v M aryland & V irginia Milk P ro

ducers Asso. 167 F Supp 799,

Headnote 7 809 (DC DC), affd 362 US

458, 4 L ed 2d 880, 80 S Ct

847. The Court has also approved the

practice of D istrict Courts of reta in ing ju

risdiction in such cases for fu tu re modifi

cations of the ir decrees, a practice which

has also not been considered inconsistent

w ith the finality of the original decrees.

See Associated P ress v United S tates, 326

US 1, 22, 23, 89 L ed 2013, 2031, 2032, 65

S Ct 1416; Lorain Journal Co. v United

S tates, 342 US 143, 157, 96 L ed 162, 173,

72 S Ct 181. But cf. United S tates v

Schine Chain Theatres, Inc. 63 F Supp

229, 241, 242 (DC WD NY), 2 D & J 1815,

mod 334 US 110, 92 L ed 1245, 68 S Ct

947; United S tates v Param ount Pictures,

Inc. 70 F Supp 53, 72, 75 (DC SD NY), 2

D & J 1682, mod 334 US 131, 92 L ed 1260,

68 S Ct 915, revised in accordance with

th is Court’s .mandate, 85 F Supp 881, 898

901, 2 D & j 1690, affd sub nom. Loew s,

Inc. v United S tates, 339 US 974, 94 L ed

1380, 70 S Ct 1032, in which review did

aw ait the entry of specific and detailed

provisions for disposition of the defend

an ts’ assets.

A ■■ A ■ -vN’fcJil

sfc fy>

. . . . . . . / w

. . ■ ■ ■ .. ■ . -

l i

3

3m

M +s A vs1*!

■ ■ .■■ •

.vx-S

' ' V - H.'-n

-A-;.; •• - - : ■

- : ■ /|

S t 1* 5:

’’ j-»4' is '~i ,- , ■ .

< p8 v ;

fa**} ir.

̂ ■ ;

S - . ■• .TV i

f ■--■-‘.Sr ■ i<

*we - S»- t |

»I

v->~

V V - ■..........

v r r .

- *

>' afe

* *•_, , J ... - -a, -

;

at *

526 U. S. SUPREME COURT REPORTS 8 L ed 2d

the entire complaint filed by the

Government. fim X P f K L j , f

relief was passed upon. .Full divest-

itJSPPW ^W fW PiPW m ey’s stockl t t r i e u jy

and assets was expressly required.

Appellant was permanently enjoined

from acquiring or having any fur

ther interest in the business, stock

or assets of the other defendant in

the suit. The single provision of the

judgment by which its finality may

be questioned is the one requiring

appellant to propose in the immedi

ate future a plan for carrying into

effect the court’s order of divestiture.

However, when we reach the merits

of, and affirm, the judgment below,

the sole remaining task for the Dis

trict Court will be its acceptance of,

a plan for full divestiture, and the

supervision of the plan so accepted.

Further rulings of the District

Court in administering its decree,

facilitated by the fact that the de

fendants below have been required

to maintain separate books pendente

lite, are sufficiently independent of,

and subordinate to, the issues pre

sented by this appeal to make the

case in its present posture a proper

one for review now.15 Appellant

here does not attack the full divesti

ture ordered by the District Court

as such; it is appellant’s contention

*[370 US 309]

that *under the facts of the case, as

alleged and proved by the Govern

ment, no order of divestiture could

have been proper. The propriety

of divestiture was con-

Headnote 9 sidered below and is dis

puted here on an “all or

nothing” basis. It is ripe for review

now, and will, thereafter, be fore

closed. Repetitive judicial consider

ation of the same question in a single

suit will not occur here. Cf. Radio

Station WOW v Johnson, supra (326

US at 127) ; Catlin v United States,

324 US 229, 233, 234, 89 L ed 911,

915, 916, 65 S Ct 631; Cobbledick v

United States, supra (309 US at 325,

330).

A second consideration support

ing our view is the character of the

decree still to be entered in this suit.

It will be an order of full divesti

ture. Such an order requires care

ful, and often extended, negotiation

and formulation. This process does

not take place in a vacuum, but,

rather, in a changing market place,

in which buyers and bankers must

be found to accomplish the order of

forced sale. The unsettling influ

ence of uncertainty as to the affirm

ance of the initial, underlying deci

sion compelling divestiture would

only make still more difficult the

task of assuring expeditious en

forcement of the antitrust laws.

;stit'ure had been

T h rtt^ J ic interest, as well as that

of the parties, would lose by such

procedure.

15. Cf. F orgay v Conrad (US) 6 How

201, 12 L ed 401; Carondelet Canal & Nav.

Co. v Louisiana, 233 US 362, 58 L ed 1001,

34 S Ct 627; Radio Station WOW v John

son, 326 US 120, 89 L ed 2092, 65 S Ct 1475;

Cohen v Beneficial Industrial Loan Corp.

337 US 541, 98 L ed 1528, 69 S Ct 1221.

The details of the divestiture which the

D istrict Court will approve cannot affect

the outcome of the basic litigation in this

case, as the details of an eminent domain

settlem ent m ight moot the claims of the

condemnee in th a t type of suit. See Re

public N atural Gas Co. v Oklahoma, 334

US 62, 92 L ed 1212, 68 S Ct 972; Grays

H arbor Logging Co. v Coats-Fordney Co.

(W ashington ex rel. Grays Harbor Log

ging Co. v Superior Ct.) 243 US 251, 61 L

ed 702, 37 S Ct 295.

n-’T'-"™

c

prior

of the

order*

found

viewe

dec r>*.

to con

sub jet

broug

with

of the

And

unani

and i

Distr.

enteri

amen

broug

16.

ally i

antitri

ever,

the si'

eludes

sough

of its

consid

E. g-,

224 l

236 l

Unite

& Co.

872, ;

1213.

which

it cor

which

liitr

Unite

64 L

sub a

Stale-

5 ith

Inc. fj

la te r

Unit*

*SS- A-C

■■

BROWN SHOE CO.

370 US 284, 8 L ed

Lastly, holding the decree of the

District Court in the instant case

less than “final” and, thus, not ap

pealable, would require a departure

faggrj^sgttled course of tlT6' CUlUUr

pracHceT™

iWWST- antitrust decrees contem

plating either future divestiture or

other comparable remedial action

*[370 US 310]

prior to the formulation and *entry

of the precise details of the relief

ordered. No instance has been

found in which the Court has re

viewed a case following a divestiture

decree such as the one we are asked

to consider here, in which the party

subject to that decree has later

brought the case back to this Court

with claims of error in the details

of the divestiture finally approved.16

And only two years ago, we were

unanimous in accepting jurisdiction,

and in affirming the judgment of a

District Court similar to the one

entered here, in the only case under

amended § 7 of the. Clayton Act

brought before us at a juncture com-

16. The Court has, of course, occasion

ally reviewed varying facets of single

an titru st cases on separate appeals. How

ever, such cases are distinguishable from

the situation a t bar. Thus, one group in

cludes cases in which the Government first

sought appellate review from dismissals

of its complaints, w hereafter the Court

considered the orders entered on remand.

E. g., United S tates v Terminal R. Asso.

224 US 383, 56 L ed 810, 32 S Ct 507;

236 US 194, 59 L ed 535, 35 S Ct 408;

United S tates v E. I. Du Pont de Nemours

& Co. 353 US 586, 1 L ed 2d 1057, 77 S Ct

872; 366 US 316, 6 L ed 2d 318, 81 S Ct

1243. A nother group includes cases in

which the Government appealed from w hat

it considered to be inadequate decrees, in

which the Court la te r considered the fu r

the r relief ordered on remand. E. g.,

United S tates v Reading Co. 253 US 26,

64 L ed 760, 40 S Ct 425, la ter considered

sub nom. Continental Ins. Co. v United

States, 259 US 156, 66 L ed 871, 42 S Ct

540; United States v Param ount Pictures,

Inc. 334 US 131, 92 L ed 1260, 68 S Ct 915,

la ter considered sub nom. Loew’s, Inc. v

United States, 339 US' 974, 94 L ed 1380, 70

S Ct 1032. And appeals in which the de-

v UNITED STATES 527

2d 510, 82 S Ct 1502

parable to the instant litigation.

See Maryland & Virginia Milk

Producers Asso. v United States, 362

US 458, 472, 473, 4 L ed 2d 880,

890, 891, 80 S Ct 847.17 A fear of

piecemeal appeals because of our

adherence to existing procedure can

find no support in history. Thus,

*[370 US 311]

the substantial body *of precedent

for accepting jurisdiction over this

case in its present posture supports

the practical considerations pre

viously discussed. We believe a

contrary result would be inconsist

ent with the very purposes for which

the Expediting Act was passed and

that gave it its name.

III.

Legislative History.

This case is one of the first to

come before us in which the Govern

ment’s complaint is based upon al

legations • that the appellant has

violated § 7 of the Clayton Act, as

that section was amended in 1950.18

tails of a divestiture were made a prim ary

issue have followed the en try of such or

ders upon the filing of consent decrees,

in which the underlying requirem ents of

divestiture were never previously present

ed. E. g., Swift & Co. v United States,

276 US 311, 72 L ed 587, 48 S Ct 311;

United S tates v Swift & Co. 286 US 106,

76 L ed 999, 52 S Ct 460; Chrysler Corp. v

United States, 316 US 556, 86 L ed 1668,

62 S Ct 1146; Ford Motor Co. v United

States, 335 US 303, 93 L ed 24, 69 S Ct 93.

Cf. International H arvester Co. v United

S tates. 248 US 587, 63 L ed 434, 39 S Ct 5;

274 US 693, 71 L ed 1302, 47 S Ct 748.

17. Cf. Jerrold Electronics Corp. v U nit

ed States, 365 US 567, 5 L ed 2d 806, 81

S Ct 755, affg 187 F Supp 545, 563-567

(DC ED P a).

18. M aterial in italics was added by the

amendments; m aterial in brackets was de

leted. “No corporation engaged in com

merce shall acquire, directly or indirectly,

the whole or any p art of the stock or other

share capital and no corporation subject

to the jurisdiction o f the Federal Trade

Commission shall acquire the whole or any

part of the assets of another corporatio:

engaged also in commerce, where in any

. . . ... .. . . '■ '■ ■ ■ ■ •■ •■ ■ ■ .■ ' ■

Sa.fe.i

.A ,* ' > * <. ̂ - • t •

BROWN SHOE CO. v UNITED STATES

370 US 294, 8 L ed 2d 510, 82 S Ct 1502

SEPARATE OPINIONS

557

*[370 US 355]

*Mr. Justice Clark, concurring.

I agree that so long as the Ex

pediting Act, 15 USC § 29, is on the

books we have no alternative but

to accept jurisdiction in this case.

The Act declares that appeals in

civil antitrust cases in which the

United States is complainant lie

only to this Court. It thus deprives

ittfeiffiSilfiSiiii,1" ,p| (Us)nni*foA

.eal and thi

consideratio , .....

Under our system a party should be

entitled to at least one appellate re

view, and since the sole opportunity

in cases under the Expediting Act

i® in this Court we usually note

jurisdiction. A fair consideration of

the issues requires us to carry out

the function of a Court of Appeals

by examining the whole record and

resolving all questions, whether or

not they are substantial. This is a

great burden on the Court and sel

dom results in much expedition, as

in this case where 21 years have

passed since the District Court’s de

cision. .

On the merits the case presents

the question of whether, under § 7

of the Clayton Act, the acquisition

by Brown of the Kinney retail stores

may substantially lessen competi

tion in shoes on a national basis or in

any section of the country.1 To me

§ 7 is definite and clear. It prohibits

acquisitions, either of stock or as

sets, where competition in any line

of commerce in any section of the

country may be substantially les

sened. The test as stated in the

Senate Report on the bill is whether

there is “a reasonable probability”

that competition may be lessened.

An analysis of the record indi

cates (1) that Brown, which makes

all types of shoes, is the fourth

largest manufacturer in the coun

try ; (2) that Kinney likewise manu

factures some shoes but deals pri

marily in retailing, having almost

400 stores that handle a substantial

*[370 US 356]

volume *of sales; (3) that its acquisi

tion would give Brown a total of

some 1,600 retail outlets, making it

the second largest retailer in the

Nation; (4) that Kinney’s stores are

on both a national and local basis

strategically placed from a retail

market standpoint in suburban areas

or towns of over 10,000 population;

(5) that Kinney’s suppliers are

small shoe manufacturers; (6) that

Brown’s earlier acquisitions, seven

in number in five years, indicate a

pattern to increase the sale of Brown

shoes through the acquisition of in

dependent outlets, resulting in the

loss of sales by small competing

manufacturers; (7) that statistics

on these outlets indicate that Brown,

after acquisition, has materially in

creased its shipments of Brown

shoes to them, some as much as

50% ; and (8) that the acquisition

would have a direct effect on the

small manufacturers who previously

enjoyed the Kinney requirements

market.

It would appear that the relevant

line of commerce would be shoes of

all types. This is emphasized by

the nature of Brown’s manufactur

ing activity and its plan to integrate

the Kinney stores into its opera

tions. The competition affected

thereby would be in the line handled

by these stores which is the full

line of shoes manufactured by

Brown. This conclusion is more in

keeping with the record as I read

it and at the same time avoids the

Ported'on6 th is t ^ o ^ ^ th e r e 0 is n e e ^ to m onopoly!^ tendency to create ,

••

__ __ . .m a-i- - « . a.

*&*-*■

■mm

■

i f

:',3i

jA

t s:m

, ' *

, ■■■-.

* - •*■

:

55S U. S,

charge of splintering the product

line. Likewise, the location of the

Kinney stores points more to a na

tional market in shoes than a num

ber of regional markets staked

by artificial municipal boundaries.

Brown’s business is on a national

scale and its policy of integration of

manufacturing and retailing is on

that basis. I would conclude, there

fore, that it would be more reason

able to define the line of commerce

as shoes—those sold in the ordinary

retail store—and the market as the

entire country.

*[370 US 357]

*On this record but one conclusion

can follow, i. e., that the acquisition

by Brown of the 400 Kinney stores

for the purposes of integrating

their operation into its manufactur

ing activity created a “reasonable

probability” that competition in the

manufacture and sale of shoes on a

national basis might be substantial

ly lessened. I would therefore af

firm.

Mr. Justice Harlan, dissenting in

part and concurring in part.

I would dismiss this appeal for

lack of jurisdiction, believing that

the case in its present posture is pre

maturely here because the judgment

sought to be reviewed is not yet final.

Since the Court, however, holds that

the case is properly before us, I

consider it appropriate, after noting

my dissent to this holding, to ex

press my views on the merits be

cause the issues are of great impor

tance. On that aspect, I concur in

the judgment of the Court but do

not join its opinion, which I consider

to go far beyond what is necessary

to decide the case.

Jurisdiction.

ensure speedy disposition of suits in

equity brought by the United States

*[370 US 358]

under the Anti-*Trust Act.” United

States v California Co-op. Canneries,

279 US 553, 558, 73 L ed 838, 842,

49 S Ct 423. This major policy con

sideration emerges clearly from the

otherwise meager legislative history

of the Act. See HR Rep No. 3020,

57th Cong, 2d Sess (1903) ; 36 Cong

Rec 1679, 1744, 1747. It was in

keeping with this purpose that “Con

gress limited the right of review to

an appeal from the decree which dis

posed of all matters . . . and

. . . precluded the possibility of

an appeal to either [the Supreme

Court or the Court of Appeals]

. . . from an interlocutory de

cree.” United States v California

Co-op. Canneries (US) supra. For

it was entirely consistent with its

desire to expedite these cases for

Congress to have eliminated the

time-consuming delays occasioned by

interlocutory appeals either to inter

mediate courts or to this Court.

The Court’s authority to entertain

this appeal depends on § 2 of the

Expediting Act of 1903. That stat-

By taking jurisdiction over this

appeal at the present time, despite

the fact that, even if affirmed, this

case would doubtless reappear on

the Court’s docket if the terms of

the District Court’s divestiture de

cree are unsatisfactory to the appel

lant or to the Government, the Court

is paving the way for dual appeals

in all government antitrust cases

C7----- ---- -------- .i,---- -------- .„JI U!

- ' • •• . - •• VA*

t,, A..- -•> ,-v .... ■ • A. •<..,. -. ...

•' ............ ------------------------ ---------- -

OClIT REPORTS S L ed 2d

ute, in its present form, provides

(15 USC § 29): men is

such i

“In every civil action brought in the *

any district court of the United trail n

States under any of said [antitrust] cratu

Acts, wherein the United States is by no

complainant, an appeal from the lieve '

final judgment of the district court v isit:

will lie only to the Supreme Court.” ing A

(Emphasis added.) now j.

the acThe Act was passed by a Congress

which thereby “sought . . . to

•ment’

................ •- .......... -V :

The

peal i

to “r

stock

the G

joins

betwe

docs

is to

pellai

carry

der”

days

to s

tions

light

this

more

dicii

ally

final

(US

Frcr

8 6 ,1

this

Stat

& C <

2d :

the

the

vest

mat

ing

Sup

app

heft

K:»

—, ■ j j j | 1 ^ ^ ■ :-;*i';! ^ 5% *'' ... ' ' '|H |j{ g ||a |g i|g |||i|||g l|a i||il|H g M i|M H H H |' ' " '' ''' " ' ' I |

• .

...... ■ , . ■ ' ■ '

'... . .;'. : .• ' ■ 1 . '

M . ..... mm

BROWN SHOE CO.

370 US 294, 8 L ed

/ where intricate divestiture judg

ments are involved. Whether or not

such a procedure is advisable from

the standpoint of judicial adminis

tration or practical business consid

erations—and I think such questions

by no means free from doubt—I be

lieve that it is contrary to the pro

visions and purposes of the Expedit

ing Act, and that the construction

now given the Act does violence to

the accepted meaning of “final judg

ment” in the federal judicial system.

The judgment from which this ap

peal is taken directs the appellant

to “relinquish and dispose of the

stock, share capital and assets” of

the G. R. Kinney Company and en

jo in s further interlocking interests

between the two corporations. It

does hot specify how the divestiture

is to'be carried out, but directs ap-

*[370 US 359]

pellant to file “a proposed *plan to

carry into effect the divestiture or

der” and grants the Government 30

days following such filing in which

to submit “opposition or sugges

tions thereto.” When considered in

light of the District Court’s opinion,

this reservation emerges as much

more than a mere retention of juris

diction for the purpose of ministeri

ally executing a definite and precise

final judgment. See e. g., Ray v Law

(US) 3 Cranch 179, 2 L ed 404;

French v Shoemaker (US) 12 Wall

86, 98, 20 L ed 270, 271. In light of

this Court’s remarks in United

States v E. I. Du Pont de Nemours

& Co., 353 US 586, 607, 608, 1 L ed

2d 1057, 1074, 1075, 77 S Ct 872,

the District Court concluded that

the particular form which the di

vestiture order was to take was a

matter which “could have far-reach

ing effects and consequences,” 179 F

Supp, at 741, and that it would be

appropriate for the court to conduct

hearings on the manner in which the

Kinney stock ought to be disposed

v UNITED STATES 559

2d 510, 82 S C t 1502

of by,the appellant. Hence it is not

farfetched to assume that particu

lar terms of the remedy ordered by

the District Court will be contested,

and that this Court may well be

asked to examine the details relat

ing to the anticipated divestiture.

E. g., United States v E. I. Du Pont

de Nemours & Co., 366 US 316, 6

L ed 2d 318, 81 S Ct 1243.

The exacting obligation with re

spect to the terms of antitrust de

crees cast upon this Court by the

Expediting Act was commented up

on only last Term. In United States

v E. I. Du Pont de Nemours & Co.,

(US) supra, it was noted that it was

the Court’s practice, “particularly in

cases of a direct appeal from the

decree of a single judge, . . . to

examine the District Court’s action

closely to satisfy ourselves that the

relief is effective to redress the anti

trust violation proved.” 366 US, at

323; see International Boxing Club,

Inc., v United States, 358 US 242,

253, 3 L ed 2d 270, 278, 79 S Ct 245.

In the present case the Court and

the parties know nothing more of

“this most significant phase of the

case,” United States v United States

Gypsum Co., 340 US 76, 89, 95 L ed

89,101, 71 S Ct 160, than that Brown

*[370 US 360]

will generally be *required to divest

itself of any interest in Kinney.

Exactly how this separation is to

be accomplished has not yet been

determined, and there is no way of

knowing now whether both parties

to the suit will find the decree sat

isfactory or whether one or both

will seek further review in this

Court.

Despite the opportunity thus cre

ated for separate reviews of these

kind of cases at their “merits” and

“relief” stages, the Court holds that

the judgment now in effect hasi“suf-

ficient indicia of finality” (pp. 525,

526, ante) to render it appealable

.'- -■'T.® -r*s

v-' ■' ■ ' • ' '

■ '■ ■

■ :

; * ■ , • , - v ; ' ■ • ' ■ - ■ \

. '

4-*kSv-**,#** i*v3?*>S' • •Tl-r'/'S

' 'Y--7•■■ i-i::'.j L . V ; ' ' ' i : ■■VLiS:aiiv\PPP : v: .

:s * l

■

^-.'■•i-.# i t

«*.' < m : ,.v^

«

K— >1

- . j■ .--- . I

f. ' -.v» i

fcL. . . ~ - ^ * k .

►••••-... • •• ".-•

p.-;<.‘.->-v-yj6

| ' •

U. S. SUPREME COURT REPORTS560

now, notwithstanding that the terms

of the ordered divestiture have not

yet been fixed. This conclusion is

based upon three discrete considera

tions, none of which, in my opinion,

serves to overcome the “final judg

ment” requirement of the Expedit

ing Act, as that term has hitherto

been understood in federal law.1

8 L ed 2d

First. The Court suggests that,

any further proceedings to be con

ducted in the District Court are

“sufficiently independent of, and sub

ordinate to, the issues presented by

this appeal” to permit them to be

considered and reviewed separately.

m e m * .

___ _ _ _

the"possibility, as did Cohen v Bene

ficial Industrial Loan Corp., 337 US

541, 93 L ed 1528, 69 S Ct 1221, and

Forgay v Conrad (US) 6 How 201,

12 L ed 404, that a delay in appellate

review would result in irreparable

*[370 US 361] _

*harm, equivalent in effect to a denial

of any review on the point at issue.

See 337 US, at 546; 6 How, at 204.

Nor is this a case in which the com

plaint’s prayers for relief are so di

versified that the resolution of one

branch of the case “is independent

of, and unaffected by, another litiga

tion with which it happens to be

entangled.” Radio Station WOW,

Inc. v Johnson, 326 US 120, 126, 89

L ed 2092, 2099, 65 S Ct 1475; see

Carondelet Canal & Nav. Co. v

Louisiana, 233 US 362, 372, 373, 58

L ed 1001,1005, 34 S Ct 627 ; Forgay

v Conrad (US) supra.

If the appellant were compelled to

await the entry of a particularized

divestiture order before being

granted appellate review, it would

suffer no irremediable loss; indeed,

in this case the merger was allowed

to proceed pendente lite, so any de

lay, to the extent that it could affect

the parties, would benefit the appel

lant. Nor can it well be suggested

that the particular conditions under

which the divestiture is to be exe

cuted are matters that are only for

tuitously “entangled” with the mer

its of the complaint. Despite the

seemingly mandatory tone of the

sTon*** “divestiture” judgment now before

***tfs, the plain fact remains that it is

m by its otvn terms inoperative to a

substantial extent until further pro

ceedings are held in the District

Court. Unlike the cases relied upon

by the Court, therefore, this case

comes up on appeal before the appel

lant knows exactly what it has been

ordered to do or not to do. This is

surely not the type of judgment

“which ends the litigation on the

merits and leaves nothing for the

court to do but execute the judg

ment.” Catlin v United States, 324

US 229, 233, 89 L ed 911, 916, 65

S Ct 631; see Covington v Covington

F irst Nat. Bank, 185 US 270, 277,

46 L ed 906, 908, 22 S Ct 645.

Second. The Court finds signifi

cant the “character of the decree

still to be entered in this suit.”

supra, p. 526. Since the order of full

divestiture requires “careful, and

1. “A final judgm ent is one which dis

poses of the whole subject, gives all the

relief th a t was contemplated, provides

with reasonable completeness, fo r giving

effect to the judgm ent and leaves nothing

to be done in the cause save to superin-

tend, m inisterially, the execution of the de

cree.” Louisa v Levi (CA6 Ky) 140 F2d

512, 514. See, e. g., G rant v Phoenix Mut.

L. Ins. Co. 106 US 429, 27 I, ed 237, 1 S Ct

414; Taylor v Board of Education (CA2

NY) 288 F2d 600. .

W

''' ft ? - ■ -V : . K ■

y.« - . ;■

i JV ~ J......... .̂..

— .:..........:

BROWN SHOE CO.

370 US 294, 8 L ed

often extended, negotiation and for

mulation-,” ante, p. 526, it is sug

gested that a delay in carrying out

its terms might render them im

practical or unenforceable. Apart

*[370 US 362]

from the fact that this policy con

sideration is more appropriately ad

dressed to the Congress than to this

Court, it appears to me to call for a

result directly contrary to that

reached by the Court. For if the

terms of the divestiture are indeed

so difficult to formulate and so in

terrelated with market conditions,

it is most unlikely that the decree

to be issued by the District Court f

will turn out to be satisfactory to,

both parties. Consequently, on the

Court’s own reasoning, a second ap

pearance of this case on our docket

is not an imaginative possibility but

a reasonable likelihood. In stating

that the divestiture portion of this

judgment “is disputed here on an

all or nothing’ basis,” and that “it

is ripe for review now, and will

thereafter, be foreclosed,” ante, p.’

526, the Court can hardly mean that

either the appellant or the Govern

ment will be precluded from seeking

review ,of the divestiture terms if

it deems them unsatisfactory. In

deed, neither side on this appeal has

addressed itself to the propriety of

the divestiture remedy, as such, that

!s independents of the question

whether the merger itself runs afoul

of the Clayton Act.

v UNITED STATES 5Gt

2d 510, 82 S Ct 1502

affirmed then an appeal on the ques

tion of relief is improbable. For

insofar as complex “negotiation and

formuJation’’ is a factor, the prob

ability of an appeal is equally likely

m either instance.

Moreover, if it is delay between

formulation of the decree and its

execution that is thought to be dam

aging, what reason is there to believe

that this delay or its hazards will

be any greater if the entire case is

brought up here once than if review

is separately sought from the di

vestiture decree once its terms have

been settled? Nor can it be main

tained that if the merits are now

[8 L ed 2d]—36

, T\ TheCour t ’s final reason

for holding this judgment appeal

able is that similar judgments have

often been reviewed here in the past

with no issue ever having been

raised regarding jurisdiction. But

, , *[370 US 363]

n Cf ! f are Region ^ i c h have

echoed the answer given by Chief

Justice Marshall to a contention that

the Court was bound on a jurisdic

tional point by its consideration on

the merits of a case in which the

jurisdictional question had gone un

noticed: “No question was made, in

that case, as to the jurisdiction It

passed sub silentio, and the court

does not consider itself as bound by

7TTs\ Case‘ ’ United States v More

“W am 159’ 172’ 2 L ed

m r i V United States,

G ^ r A n n o ’ n54’ 30 L ed 207’ 209>

L S £ f I A t ; ? ’°'SS v Burke> 146 US 8^, 87, 36 L ed 896, 898, 13 S Ct 22-

Louisville Trust Co. v Knott, 191 Us'

225, 236, 48 L ed 159, 163, 24 S Ct

119; New v Oklahoma, 195 US 252,

256> 49 0L ed 182, 183, 25 S Ct 68;

United States ex rel. Arant v Lane

245 US 166, 170, 62 L ed 223 S’

38 S Ct 94; Stainback v Mo Hock Ke

Lok p 0, 336 US 368, 379, 93 L ed

741, 749, 69 S Ct 606; United States

A- Tucker T™ck Lines, Inc.

344 US 33, 38, 97 L ed 54, 58 73

S Ct 67. The fact that the Court

may, in the past, have overlooked

the lack of finality in some of the

judgments that came here for re

view in similar posture to this one

does not now free it from the re-

quii ements of the Expediting Act

Nor does the fact that none of the

cases reviewed in what now appears

• •< ,■ - • - i

■ f r A i T ft. -A. - y--;; y t i j i C C R * A T

- ft--. -V .. i-.- ■ . ■

- »

.

'

■ ' , . ... - ■ .? ■■■--,-• ■

#S§Si§

«&s' s s i

p r a - r - 'U " ^ " ---— ----- - T — T— T-fT -

■■'■■■' ' ■. ' ■' ■ ' ' ■

. -' . • • ■

'"-'1

-*:*^*i**^ **JBi*#W

?**§

U. S. SUPREME COURT REPORTS 8 L ed 2d

f»-

fe* -

/•

'TT?

> ~

i , .... : *

?■

AS?

-

::«■

- . " | ] I t

i; ' •• X| ‘ >, ’:

k ;" 4$ ' u

:» ; t

fe— A ; i

■' ' U- :

(ferKsSKS..t

r..■■■‘-™tfcsiKgir

.

to have been an interlocutory stage

was ever appealed again justify dis--

regard of the statute. This history

might point to the desirability of an

amendment to the Expediting Act,

but it does not make into a “final

judgment” a decree which reserves

for future determination the terms

of the precise relief to be afforded.

The Court suggests that a “prag

matic approach” to finality is called

for in light of the policies of the

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure,

which direct the “just, speedy, and

inexpensive determination of every

action.” Ante, p. 524. But this mis

conceives the nature of the issue

that is presented. Whether this

judgment is final and appealable is

not a question turning on the Fed

eral Rules of Civil Procedure or on

any balance of policies by this Court.

Congress has seen fit to make this

Court, for reasons which are less

than obvious, the sole appellate tri

bunal for civil antitrust suits in-'

*[370 US 364]

"stituted by the United ^States. In so

doing, it has chosen to limit this

Court’s reviewing power to “final

judgments.” Whether the first of

thesb legislative determinations,

made in 1903, when appeal as of

right to this Court was the rule

rather than the exception, should

survive the expansion in the Court’s

docket and the development, pursu

ant to the Judiciary Act of 1925, of

this Court’s discretionary certiorari

jurisdiction, may never have been

given adequate consideration by the

Congress.2

2. F or example, the report which ac

companied the 1925 Act to the floor of the

Senate said of the cases in which direct

appeal from a D istrict Court to the Su

preme Court was retained: “As is well

known, there are certain cases which,

under the presen t law, may be taken di

rectly from the d istric t court to the Su

preme Court. W ithout entering into a

description of these four classes of cases,

At this period of mounting dock

ets there is certainly much to be said

in favor of relieving this Court of

the often arduous task of searching

through voluminous trial testimony

and exhibits to determine whether

a single district judge’s findings of

fact are supportable. The legal is

sues in most civil antitrust cases are

no longer so novel or unsettled as to

make them especially appropriate

for initial appellate consideration by

this Court, as compared with those

in a variety of other areas of federal

law. And under modern conditions

it may well be doubted whether di

rect review of such cases by this

Court truly serves the purpose of

expedition which underlay the origi

nal passage of the Expediting Act.

I venture to predict that a critical

reappraisal of the problem would

lead to the conclusion that “expedi

tion” and also, over-all, more satis

factory appellate review would be

*[370 US 3C5]

achieved in *these cases were pri

mary appellate jurisdiction returned

to the Court of Appeals, leaving this

Court free to exercise its certiorari

power with respect to particular

cases deemed deserving of further

review. As things now stand this

Court must deal with all government

civil antitrust cases, often either at

the unnecessary expenditure of its

own time or at the risk of inadequate

appellate review if a summary dis

position of the appeal is made. Fur

ther, such a jurisdictional change

would bid fair to satisfy the very

“policy” arguments suggested by the

it is sufficient to say th a t under the exist

ing law these . arc cases which m ust be

heard by three judges, one of whom is a

circuit judge.” S Rep No. 362, 68th Cong.

1st Sess 3 (1924). (Em phasis added.)

This generalization was obviously erro

neous since the Expediting Act provided

for direct review in this Court of govern

ment an titru s t cases decidej by a single

d istrict judge.

[8 L ed 2d]

Court

of Ap

eraiiy

this C

to hea

the o

this <

again-

t ween

come ’

were t

review

Court.

So 1

Exped

mend

is bom

for th

decree

ion, b«

judgm

this ji:

missed

Sine

that t!

its pre

derlyii

I cot s

view o

of the

which

Distric

pared

or ini]

Court.

The

case c

conci-t

Court*,

of the

*bc, fr

Clayto

CUiili)'.- i

monop

in any

tainab;

indefi r,

§ 7 in.

. •

i i

• ;• A- A- 9

ff»<*ip"mi*!-tm$t

■ ̂ ;*v.

/vi.-.R,^..>.^iS]ri>-- &,.-:ss : * r ^ \ ‘-*.f*;j?-i.-;?-,s,:tf:~.y:

■

•-v** ..-. ^ -SWV'jOV* *-*.** j.1-•*».»* '-„c'}.?:#4s.J>.,_t!»l*l,-!~ iJ> v • ~ ■*?• v ->;

6$&h: 0i

,^.1_,.^.^r.n..-f.,l.,,lV .n...,^.r^l|l. f.m->,;i,

■' • ' -# .

BROWN SHOE CO.

. 370 US 294, 8 L ed

Court in this case. For the Courts

of Appeals, whose dockets are gen

erally less crowded than those of

this Court, would then be authorized

to hear appeals from orders such as

the one here in question. Since

this order grants an injunction

against interlocking interests be

tween Brown and Kinney, it would

come within 28 USC § 1292(a) (1)

were this not a case “where a direct

review may be had in the Supreme

Court.”

563

So long, however, as the present

Expediting Act continues to com

mend itself to Congress this Court

is bound by its limitations, and since

for the reasons already given the

decree appealed cannot, in my opin

ion, be properly considered a “final

judgment,” I think the appeal, at

this juncture, should have been dis

missed.

v UNITED STATES

2d 510, 82 S Ct 1502

pose to proscribe a combination of

this sort? Brown contends that in

finding the merger illegal the Dis

trict Court lumped together what

are in fact discrete “lines of com

merce,” that it failed to define an

appropriate “section of the coun

try,” and that when the case is prop

erly viewed any lessening of com

petition that may be caused by the

merger is not “substantial.” For

reasons stated below, I think that

each of these contentions is unten

able.

The Merits.

Since the Court nonetheless holds

that the judgment is appealable in

its present form, and since the un

derlying questions are far-reaching,

I consider it a duty to express my

view on the merits. On this aspect

of the case I join the disposition

which affirms the judgment of the

District Court, though I am not pre

pared to subscribe to all that is said

or implied in the opinion of this

Court.

The dispositive considerations

are, l[ think, found in the “vertical”

effects of the merger, that is, the

effects reasonably to be foreseen

from combining Brown’s manufac

turing facilities with Kinney’s retail

outlets. In my opinion the District

Court’s conclusions as to such effects

are supported by the record, and

suffice to condemn the merger under

§ 7, without regard to what might

be deemed to be the “horizontal”

effects of the transaction.

The question presented by this

case can be stated in narrow and

concise term s: Are the District

Court’s conclusions that the effect

of the Brown-Kinney merger may

*[370 US 366]

*be, in the language of § 7 of the

Clayton Act, “substantially to lessen

competition, or to tend to create a

monopoly” in “any line of commerce

in any section of the country” sus

tainable? In other words, does the

indefinite and general language in

§ 7 manifest a congressional pur-

1. “Line of Commerce.”—In con

sidering both the horizontal and ver

tical aspects of this merger, the Dis

trict Court analyzed the probable

impact on competition in terms of

three relevant “lines of commerce”

—men’s shoes, women’s shoes, and

children’s shoes. It rejected

Brown’s claim that shoes of differ

ent construction or of different price

range constituted distinct lines of

commerce. Whatever merit there

might be to Brown’s contention that

the product market should be more

narrowly defined when it is viewed

from the vantage point of the ulti

mate consumer (whose pocketbook,

for example, may limit his purchase

to a definite price range), the same

is surely not true of the shoe manu

facturer. Although the record con

tains evidence tending to prove that

*[370 US 367]

a shoe manufacturing *plant may be

:

~*r. JV; !'»

f a x . A

M*-W<-■ <- w. -nW '«

i ?'kiyr*’ : : *‘-#'*41 - ‘.->f :->■ s i v .* - •, v .- . - v - v - -!< 5

4 c