Memorandum of Law in Support of Motions

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1972

4 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Memorandum of Law in Support of Motions, 1972. 63b62e19-53e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/dc6b1f97-f062-4b78-afb5-2b92ac777dc7/memorandum-of-law-in-support-of-motions. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

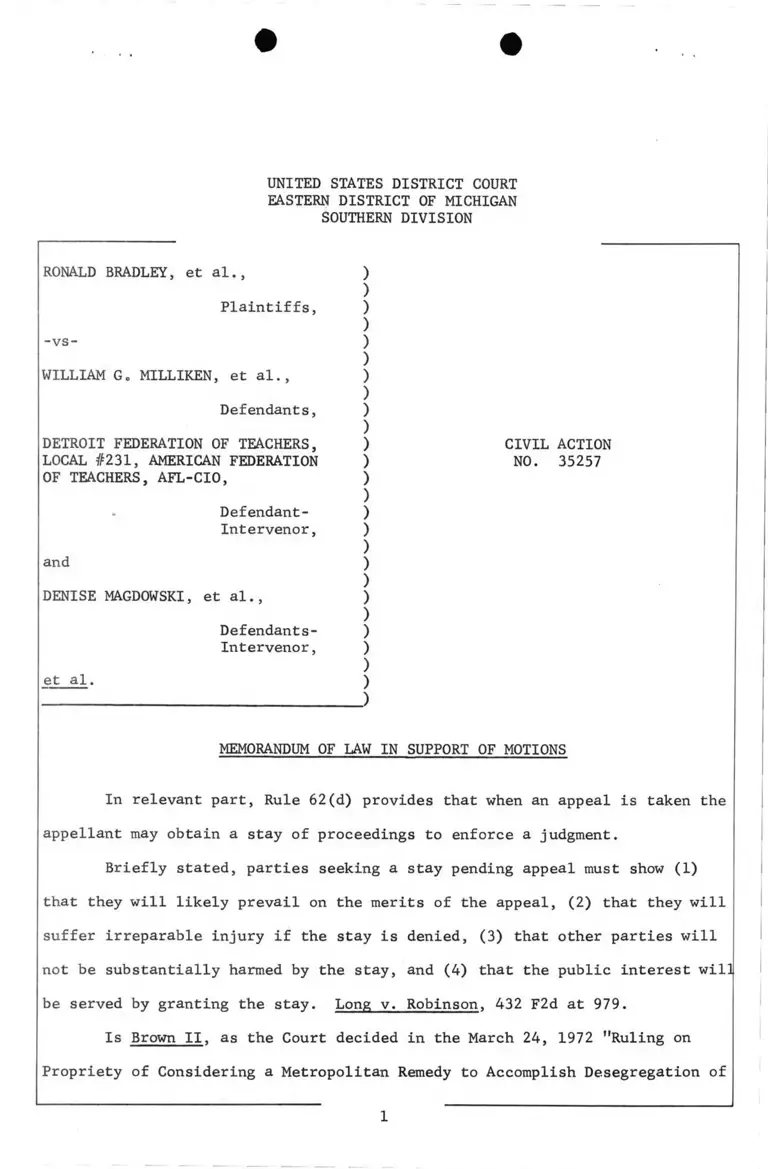

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

RONALD BRADLEY, et al., )

)

Plaintiffs, )

)

-vs- )

)

WILLIAM Go MILLIKEN, et al., )

)

Defendants, )

)

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, )

LOCAL #231, AMERICAN FEDERATION )

OF TEACHERS, AFL-CIO, )

)

- Defendant- )

Intervenor, )

)and )

)

DENISE MAGDOWSKI, et al., )

)

Defendants- )

Intervenor, )

)et al. )

_____________________________________ )

CIVIL ACTION

NO. 35257

MEMORANDUM OF LAW IN SUPPORT OF MOTIONS

In relevant part, Rule 62(d) provides that when an appeal is taken the

appellant may obtain a stay of proceedings to enforce a judgment.

Briefly stated, parties seeking a stay pending appeal must show (1)

that they will likely prevail on the merits of the appeal, (2) that they will

suffer irreparable injury if the stay is denied, (3) that other parties will

not be substantially harmed by the stay, and (4) that the public interest will

be served by granting the stay. Long v. Robinson, 432 F2d at 979.

Is Brown II, as the Court decided in the March 24, 1972 ’’Ruling on

Propriety of Considering a Metropolitan Remedy to Accomplish Desegregation of

1

the Public Schools of the City of Detroit”, dispositive of the unprecedented,

threshold and landmark question number 3 for briefing in the Court's March 6,

1972 "Notice to Counsel"?

The Court of Appeals and the Supreme Court, as the case may be, are

likely to say "no” not only for the reasons set forth in the "Objections by

Defendants-Intervenor Kerry Green et al. to Testimony and Exhibits Concerning

Metropolitan Remedy”, filed on May 4, 1972, but also for the reason that the

alternative metropolitan desegregation area and plan remedy as now granted is

inconsistent with and contrary to the admonitions in Swann at 22-23:

The constant theme and thrust of every holding from

Brown I to date is that state-enforced separation of

races in public schools is discrimination that violates

the Equal Protection Clause. The remedy commanded was

to dismantle dual school systems.

We are concerned in these cases with the elimination

of the discrimination inherent in the dual school sys

tems, not with myriad factors of human existence which

can cause discrimination in a multitude of ways on rac

ial, religious, or ethnic grounds. The target of the

cases from Brown I to the present was the dual school

system. The elimination of racial discrimination in

public schools is a large task and one that should not

be retarded by efforts to achieve broader purposes

lying beyond the jurisdiction of school authorities.

One vehicle can carry only a limited amount of baggage.

It would not serve the important objective of Brown I

to seek to use school desegregation cases for purposes

beyond their scope, although desegregation of schools

ultimately will have impact on other forms of discrim

ination. . . .

Our objective in dealing with the issues presented by

these cases is to see that school authorities exclude no

pupil of a racial minority from any school, directly or

indirectly, on account of race; it does not and cannot

embrace all the problems of racial prejudice, even when

those problems contribute to disproportionate racial

concentrations in some schools.

and at 24:

. . .The constitutional command to desegregate schools

does not mean that every school in every community must

always reflect the racial composition of the school sys

tem as a whole. . . .

2

Litigant prudence and judicial prudence, at the very least, together

caution an appropriate stay of proceedings to enforce the possible fall 1972

term metropolitan desegregation plan as ordered pending a timely and secure

appellate review of the unprecedented, threshold and landmark questions of

law and fact upon which the ultimate fall 1973 term plan as ordered in this

action is predicated.

The national significance of the action at bar is no less than this:

If Brown II is dispositive of the question of propriety of the metropolitan

remedy as ordered, then Brown I will at once thereby have been rewritten. If

this Court is affirmed on appeal, then every district court, relying upon the

Brown II instrument of equity alone, may consider and enforce an enlargement

of the desegregation area beyond which a Brown I constitutional violation is

claimed, shown and found.

All key issues are formulated and decided.

Do the unprecedented, threshold and landmark questions of law and fact

at bar sound in "remedy” or in "right and violation"?

The Court says "remedy"; we say "right and violation".

The Court's rationale is explicit.

So too is the litigant challenge.

Equity follows the law.

Equity does not create new rights. In Re Bowman, 24 F. Supp. at 384.

Where there is no legal liability, equity can create none; and equity

cannot apply a remedy where there is no right. Pewitt v. Pewitt, 240 SW2d

at 528.

Thus far the Court alone has shouldered all the burden of the momentous

question of metropolitan remedy propriety. Who is there to gainsay that the

time is now for the Court, without slightest offense to any Supreme Court

mandate, to share that lonely burden with appellate courts?

3

Nor can a moderate fall 1972 term stay be casually or cynically equated

with inequitable and insensitive delay in the vindication of the plaintiffs'

constitutional rights. Nothing militates against a stay order so fashioned

so as to permit both the unhurried continuity of committee preparation of the

fall 1973 term metropolitan plan as well as implementation of the plaintiffs'

Detroit-only plan on an interim basis pending appeal.

Appeals will surely move on apace.

A problem of responsible advocacy at bar is selecting, with the Court's

assistance, a route of timely law and fact appeal secure from another round

of appeal challenge and possible dismissal.

Citizen to citizen, in good faith, we call upon the plaintiffs and

their able counsel, in the light of the totality of public interest in this

action, to consider realistically what if any substantial harm can result if

a stay is granted as moderately suggested. Realities being what they are, is

there not as much danger of substantial harm to the cause itself of vindicat

ing constitutional rights if a prudent stay is not granted merely for lack of

the plaintiffs' consent?

Respectfully submitted,

ROBERT J. LORD

Attorney for Defendants-Intervenor

Kerry Green, et al.

8388 Dixie Highway

Fair Haven, Michigan 48023

Telephone: 725-4231

4