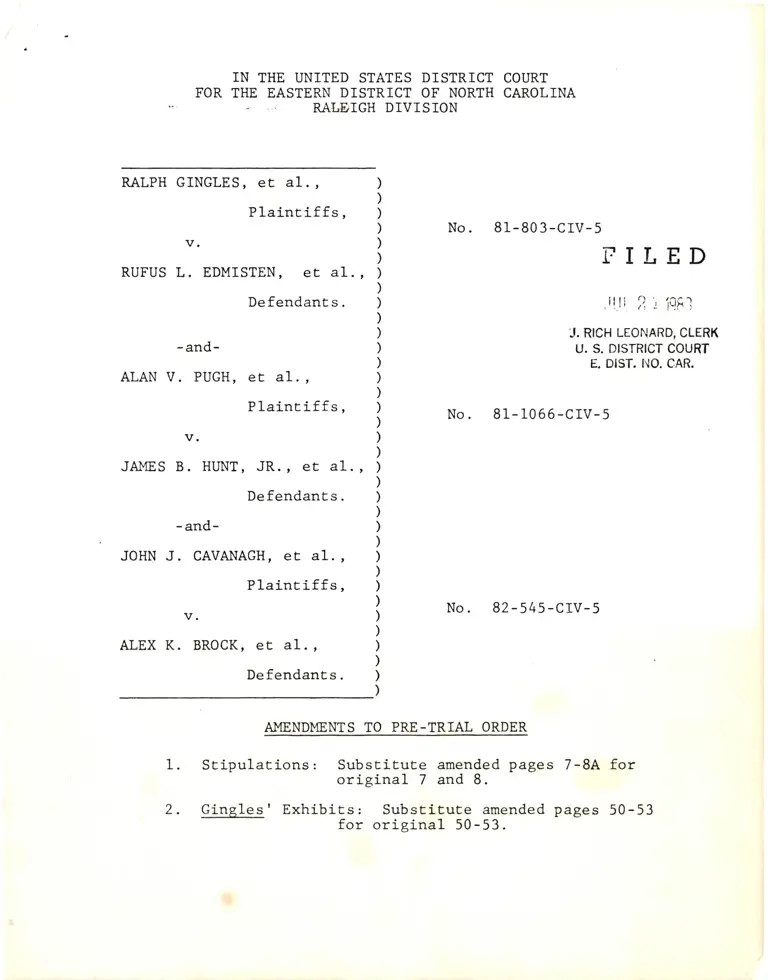

Pugh v. Hunt and Cavanagh v. Brock Amendments to Pre-Trial Order

Public Court Documents

July 21, 1983

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Pugh v. Hunt and Cavanagh v. Brock Amendments to Pre-Trial Order, 1983. b49da092-e192-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/dcabe1bf-ef0e-43ba-8ca0-4962ae52a5c1/pugh-v-hunt-and-cavanagh-v-brock-amendments-to-pre-trial-order. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

RATEIGH DIVISION

RALPH GINGLES, et 41.,

Plaintiffs,

v.

RUFUS L. EDMISTEN, et al.

Defendants.

-and-

ALAN V. PUGH, eE a1.,

Plaintiffs,

v.

JAI'{ES B. HlrNT, JR., et al.

Defendants.

-and-

JOHN J. CAVANAGH, €t 41.,

Plaintiffs,

v.

ALEX K. BROCK, €E aL.,

Defendants.

No. 81-803-CIv-5

rILED

,r! rr 2 f ,iqE I

J. RICH LEONARD, CLERK

U. S. DISTRICT COURT

E. DIST. t!O. CAR.

No. 81-1066-cIv-5

)

)

)

)

)

)

,)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

,)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

No. 82-545-CIv-5

AI.,IENDMEMS TO PRE-TRIAL ORDER

1. Stipulations: Substitute amended pages 7-8A for

original 7 and 8.

2. Gingles' Exhibits: Substituce amended pages 50-53

for original 50-53.

3. Defendants' Exhibits: Substitute amended pages

62-65 for original 62-65.

4. Defendants ' I,Iitnesses : Add page 75b.

5. Designation of Pleadings: Substitute amended pages

76A-79 for original 76A-79.

This 2l a.y of July, 1983.

Etorney

Defendants

e

?

J.

ntiffs "u;)'" 2

-2-

44. On ApriL 27, L982, Chapter 3 (House Bill 2) of the Session

Laws of the Second Extra Session, L982, which provided, among other

maCters, for alternative dates for North Carolina's filing period

and primaries. (Exhibit FF).

45. By letter of Aprit 30, L982, the United States Attorney

General indicated that he would not interpose an objection to

ChapEers I and 2 of the Session Laws of the Second Extra Session,

I982, (the amended House and Senate redistricting plans) but

interposed an objection to the candidate filing period and primary

election date contained in Chapter 3 of said Session Laws. (Exhibit

GG. ) The State of North Carolina, through the North Carolina State

Board of Elections, responded to the object.ion of the United States

Attorney General on May 6 , 1982, by revising the l9B2 primary

elect ion timetable for the State of Nor:th Carolina, providing inter

alia, that the date of the primary elections for L982 be changeo

Erom June I0, 1982, to June 29, L982, ES is exhibiteo by the letter

and attachments to I*,1r. William Bradfor:d Reynolds from Mr. Alex K.

Brock of the State Board of Elections. (Exhibit HH).

46. By letter of May 20 , L982, the Office of the Attorney

General indicated it would not interpose an objection to the revised

L9B2 primary election timetable for L982 as amended by the State

Board of Elections. (Attachment II).

47. In accordance with the revised timetable and with Chapters

2 and 3 of the Sessions Laws of the Second Extr:a Session, Primary

and General Elections were held for the North Carolina General Assembly

in 1982.

48. Exhibits AAA-UUU are accurate copies of the Journals of

the North Carolina House of Representatives of the North Carolina

Senate, the minutes of the House and Senate Redistricting Committees

and of the transcripts of committee meetings and fl-oor debates

relating to redistricting. The transcripts are accurate transcrip-

tions of those portions of the meetings which they proport to

transc ribe .

AAA - NC General Assembly Extra Session L982 Redistricting

Public Hearings of February 4, L982 - Minutes, Transcripts

and Attachments

BBB - NC General Assembly Fir:st Extra Session 1982 House and

Senate Journals

CCC - IgBl Senate Redistr:icting Munutes of Senate Redistricting

Committee Meetings and Other Supplementary l"laterials

DDD - NC Senate Legislative Redistricting First Extra Session

L982 (February) Senator MarshaII A. Rauch, Chairman

EEE - Verbatim Transc:'ipt of the Senate of the Gener:al Assembly

of the Stat.e of NC Second Extra Session, April I9B2

-7-

Amended

FFF - I981 General AssembIy, Regular Sessions 1981 Senate

Legislative Redistricting Committee Meeting Transcripts

GGG - I98I Senate Redistricting october Special Session -

I"linutes and Supplementary Related Materials

HHH - NC General Assembly (Second Extra Session I9B2)

Bi1Is, Amendments, RoIl CaIlsr dod Maps

III - Journal of the Senate of the General Assembly of the

State of NC - Second Extr:a Session 1982

JJJ - NC General Assembly L982 Fir:st Extra Session - Transcript

of Senate Proceedings February 9-10-I1, L9B2 Floor

Deba te

KKK - NC General Assembly - First Extra Session L9B2 (l'ebruary)

Summary of Proceedings rrith Supplementary Materials (Senate)

LLL - House Legislative Redistricting, February Session - l9B2

MI',lIl - NC House of Representatives IgBI Legislative Reapportion-

ment History and Information

NNN - NC House Reapportionment October I9B1: Legislative

History for HB-L428

OOO - House Legislative Redistricting Apr:iI Session - 1982

PPP - NC General Assembly - Fir:st Extra Session L982 HB-I

(Session Laws Chapter 4): BiII Drafts, Amendments Offered,

and RoII CaIls

QOQ - NC General Assembly (Second Extra Session I9B2) - House

Journal

RRR - 19Bl General AssembIy, Regular Sessions L9BI House

Legislative RedisEr:icting Committee l"leeting Transcripts

SSS - Volume I Minutes House Legislative Redistricting

Committee - February 2, L982

Volume 2 l4inutes House Legislative Redistricting

Committee - February 3, L9B2

TTT - North Carolina General Assembly Second Extra Session - 1982

Senate Legislative Redistricting Committee

Meetings Minutes and TranscriPts

UUU - NC General Assembly (Second Extra Session 1982) - House

Leg islative Redistr:ict ing Commi ttee - Meeting TI:anscripts

(Apri1, t9B2 )

-B-

Amended

C. Other Stipulations of Fact

49 . The vote abs tracts, voter tu!:nou t f igures , and voter

registration figures used by Bernard Grofman and Thomas Hofeller

as the basis of their analyses of or testimony about voting patterns

are accurate and genuine. Any party or witness may refer to the

information indicated in these documents during the course of t,he

trial of these actions wit,hout further foundation.

50. The following is an accurate list of the black candidates

who filed to run in the indicated elections. AII candidates vrere

Democrats unless otherwise indicated. This is not a complete list

of all elections in which there were black candidates.

[go to next page)

-8A-

Amended

III. LISTS OF EXHIBITS

A. Gingles Plaintiffs

Number

List of Exhibics

Title

1. Vita of Bernard N. Grofman*

2. Senate Plan, Chapter 2, L982 2nd Exrra

Session (Mapl

3. House Plan, Chapter 1, L982 2nd Extra

Session (Map;

4. (a) and (b) House Districr 36, Mecklen-

burg County, Map and Legend

5. (a) and (b) House Districr 39, ForsyEh

County (Part), Map and Legend

6. (a) and (b) House District 23, Durham

County, Map and Legend

7. (a) and (b) House Districr 2L, Wake

County, Map and Legend

8, Wilson,

, Map and

22, Mecklen-

Map and

2, Map and

Defendants

Obj ec t ion

No Objection

No Objection

No Objection

No Objection

No Objection

No Objection

No Objection

No Objection

No ObjecEion

No Objection

No Objection

No Objection

No Objection

No ObjecEion

No 0bjection

8. (a) and (b) House Districr

Edgecombe and Nash Counties

Legend

9. (a) and (b) Senare Disrricr

burg and Cabarrus Counties,

Legend

10. (a) and (b) Senare Disrrict

Legend

13.

11. "Effects of Multimember StaEe House and

Senate DisEricts in Eight NorEh Carolina

Counties, L978-82," Grofman, 1983

L2. "An Outline for Racial Bloc VotingAnalysis, " Grofman, 1983 "

(a) and (b) Racial Bloc Voting Analysis,

Ilecklenburg CounEy, Senare L91g (primary'

and General)

(c) and (d) Racial Bloc Voting Analysis,

Cabarrus County, Senate L97B (erimary

and General)

(e) and (f) Racial Bloc Voting Analysis,

I'bcklerbug and Cab;rrn:s Corncies, Senate LgTg'(Prinary iurd General)

*Defendants have no objection to L-20 with a supporting witness.

-50-

Amended

Number Title

- 51-

Arncn de d

Defendants

Ob-i ection

No Objection

No Objection

No Objection

No Objection

No Objection

No Objection

No Objection

No ObjecEion

No ObjecEion

Nc Objection

No ObjecLion

No Objection

No 0bjection

t'Io 0b i ec ri.on

(gl Racial Bloc Voting Analysis,

Mecklenburg County, Senate f980

(Primary only)

(h) Racial Bloc Voring Analysis,

Cabarrus County, Senaie 1980 (primary

only)

(i) Racial Bloc Voting Analysis,

Mecklenburg/Cabarrus Counties, Senate

1980 (Primary only)

(j) and (k) Racial Bloc Voring Analysis,

Mecklenburg County, Senate L982 (primary

and General)

(1) and (m) Racial Bloc Voring Analysis,

Carbarrus County, Senate L982 (primary

and General)

(n) and (o) Racial Bloc Voting Analysis,

Mecklenburg/Cabarrus Counties, Senate

L982 (Primary and General)

(p) 9trSrlotte ObserveE, April 17, 1980,

epriT-T[T9-El0lTprTf ZZ,' L980 , April

30, 1gg0

L4. (a) and (b) Racial Bloc Voring Analysis,

Mecklenburg County, House, 1980 (primary

and General)

(c) and (d) Racial Bloc VoringAnalysis,

Mecklenburg CounEy, House, 1982 (Primary

and General)

15. (a) and (b) Racial Bloc Voting Analysis,

Forsyth County, House L978 (Primary

and General)

(c) and (d) Racial Bloc Voting Analysis,

Forsyth County, House 1980 (Primary and

General

(e) and (f) Racial Bloc Voting Analysis,

Forsyth County, House L982 (Primary and

General

(h) Racial Bloc Voting Analysis, Forsyrh

County, Senate 1980 (Primary)

(a) and (b) Racial Bloc Voting Analysis,

Durham County, House L978 (Primarv and

General )

(c) Raci al BIoc Votinq Anal.,,sis, Durham

Ct)lrnE/. liortse 1980 (Genc -,ri.,t

L6

No Oblj ec tion

Number Title

(d) and (e) Racial- BLoc Voting Analysis,

Durham County, House L982 (Primary and

General )

(f) Racial Bloc Voting Analysis, Durham

County, Senate 1978 (General)

L7. (a) Racial Bloc Voting Analysis, I.lake

County, House 1978 (Primary)

(b) and (c) Racial Bloc Voting Analysis,

l.Iake County, House 1980 (Primary)

(d) and (e) Racial Bloc Voting Analysis,

Wake County, House L982 (Primary and

General )

18. (a) Racial Bloc Voting Analysis,

Edgecombe County, House L982 (Primary)

(b) Racial Bloc Voting Analysis, Wilson

County, House L98Z (Primary)

(c) Racial Bloc Voting Analysis, Nash

County, House L982 (Primary)

(d) Racial Bloc Voting Analysis, House

DistricE No. 8, House L982 (Primary)

(e) and (f) Racial Bloc Voting Analysis,

Edgecombe CounEy, Congress L982 (First

and Second Primaries)

(g) and (h) Racial Bloc Voting Analysis,

Wilson County, Congress L982 (First and

Second Primaries)

(i) and (j) Racial Bloc Voting Analysis,

Nash County, Congress L982 (First and

Second Primaries)

(k) and (f) Racial Bloc Voting Analysis,

Edgecombe County Cormnission L982 (Primary

and General)

(m) Racial Bloc Voting Analysis, Wilson

County, County Conrnission L976 (Primary)

(ir) Racial tsIoc Voting Analysis, Nash

CounEy, Councy Commission L982 (Primary)

(o) and (pl Racial Bloc Voring Analysis,

l,Jilson-Edgecombe-i.lash, Congreis L982(First and Second primariei)

Defendant s

Obj ecEion

No Objection

No Objection

No Objection

No Objection

No Objection

No Objection*

No Objection

No Oojection

No Cbjection

No Objection

No Objection

No ObjecEion

No Objection

No Objection

No ObjecEion

*Defendants contend thau analysis of S5 counties is irrelevant.

-52-

Amen rlo d

Number TitIe

-53-

Defendants

Ob.i ection

No Objection

No Objection

None

(22-37 )

Relevance, materia-

lity and hearsay (as

to Ehe truth of the

substance )

19. Electoral Participation and Success

by Race, L970-1982

20. "The Disadvantageous Effects of At-

Large Elections on the Success of

Minority Candidates for the Charlotte

and Raleigh City Councils," Grofman,

1983

2L. Vita of Harry L. Warson

22. Raleigh News and Observer, L/30/L898,

CarEoon

23. Baleigh News and Observer, L0/15/1898,

Cartoon

24. E-aleigh News and Observer , 7 / 4 /L7OO,

Cartoon

25. "White People Wake Up," Leaflet, 1950

26. (a) Raleigh News and Observer, 5/26/54,

telt rt isement )

(b ) Bafe.gh_ Nglqs and Observer , 5 /21 / 54 ,(Ker iement )

(c) Raleigh NertE and g!server, 5/28/54,(Ker sement )

(d) Raleigh News and Observer, 5/28/54,,'Alt '

(e) Raleigh News and Observer, 5/29/54,(Alt risemenr )

27. (a) Raleigh News and Observer, 5lL9/60,

',Lak egregation

Issuestt

(b) (aleigh News and Observer , 5/26/60,(rak l

(c) Raleigh News and_O_EsCrve: , 5/26/60,(rak l

28. Raleigh News and Observer, 6/2/64, "Moore

Seeks Runoff"

Number

12.

ts.

15,

1.7.

18.

19.

.

2).

'.: -..

21.

22.

: --..:,*EJ

....

Memorandum dated August 27, tg}2, to

{ Rgber,t W....Spearman_ r No Objection

i ,3., i lress releaser-dateline Raleigh, ':,,.':; . ,.'': I :. .i -L-eeee, u9 LsI.Ltrs JtgJ.?;IgII Q .. :- .. 1 ..,...

....-.:...:;;...September2o,I982,with

:: 1r:,

--- Objection

14. North Carolina

February, Lggz

(summary and by

County Boards of Elections from

Letter dated January 14, 1983, to. Governor James B. .nunt, Jr.r'. ' ..

.l,ieutenant Governor James Green, . ' . . ..'.' -- '

Speaker Liston Ramsey, Representa- .'.' -.' .

.$,.ive J. Dlorth Gentry, Senator l{iLma

. C? Woodard from RobErt W. Spearnan

afia AIex X. Brock. .-No Object.ion

llinority Appointments and FmpioymentHighlights (1981), ' rr-- Relevancy

List of County Board of Elections

members and chairmen. '.

Computer print-ouf listing all

current appointments of black

citizens by Governor James B.

llunt, Jr

llinority Appoiritment !tighlights

(1e83) .

Crrrrent st.ati st j-cs cn Governo:'

Htf,t's minority appointments f or

sdLected counties.

House BilI 558 Flarch 29, 1983,

A BilI ,to be Entitled an Act to

Provide a Manner of Election of

the Wake County Board of Education

.Article from (naleigh) News and

Obte:ver, May 10, 1983, regaEE-Ing

Vernon l,lalonets opposition to

continued use of district method

of 'election of rnembers of the

Wake County School Board

:

ilearsay

Relevancy

Relevancy

ReLevancy 1

Relevancy

,:

:-.. .

-67_-

Hearsay

Title

Gingles

& Pugh

Obiectionr+_

Number

23.

24-

33.

Times

ivesr- '. .,'' : ' .:,i*i'.,';District 36, in I9B0 Democratic .

' PfimarY' : No Objection "" ' ":"'

-..1 -.. .. :. -i-'.'::..'' 26. Booklet entitled, Ihe Dsmo"ruai. ;' "i: ""''

Partv.of ryorth carffi '-

Rdlevance

2?. The Democralic Perlv of.Norlh - .

iB;3l,ina ' elan -or grqq*lzation ' Rerevance'

r;

:.

25. Articl.e from The Charlotte News, '..

28. Democratic Party Delegate Sel.ection

Plan for 1984. Relevance

29. Detailel tup showing concentrations No objection if I. .Iegenclof bl.ack population anq possible are supplied and-mao" .=.districts for lfinston-Salem accurate, based on-ieg"rra

3e . Deta.ilec r.rap,

"r,,wJ^s "or".nrraticns :'3'"lXi.l3;"*ll"--*l;11:

of, black population and possible accurate..

31 Detailed map showing concentrations

of black population and possibLe''-'' districts for Ra1eigh. -

?2 Detailed map showing concentrations

of black population and possible

'districts for Durham.

ditto

Detail.ed map showing conc€rrt.rations biot served on

of black population and possible & irrelevant,

districts for Fayetteville. same as 29-32.

-63-

I

Pla:.nii.J:f s'

otherwise,

..,

t'

Number

t34- ''

Gingles

& Pugh

Obiection

Curriculum vita df

curricurum vit'a of John sanders- :. '"o oujection

':.':::.::,

'.

.,.,_,.1 No' objection, " . l:.,.'.t

Excerpt from House Legislative

- ' '. t '.

Redistricting Subcommitt.. Meo+i__' -

. rl"l. spautdins (riom itipriiti"i . , . .. '.:'

.rledistricling Subcommitt"" fr."ting,' .

-'.

.: .. .,..

lj:!t:ury-?? l9q?, Tape l-p, 25, i'., :'. .. . . . . .. .

Excerpt from Joint pubLic

Hearing-House Redi strictin g,I'ebruary A, 1982, Tape 3-pl'1,

Iull-.I,i Grdene (from' stip"fu.iiir;'

Memorandum dated December 28,1970, from AIex K. nrock-to

Chairman ancl Executive Secretaryof County Board of Elections.

36:

37.

'39.

39-

40-

4L.

42. Rul-es and Administrative pro_. cedures lrclopted by the StaieBoard of E.'t_ectionl of North

. C.arol.ina to be in Effect for.l:- the November 7, lg7T, GenerilEJection and Until FurtherNotification by.the State Board

43. Letter.clated February 7 , LIBZ Ifrom Arthur Griffin to iouise'

. BreDnan

44. ' lr?p showing demographic distribu_tion by race statewide. . -:

45. Ratified House Bitl 796, dated

May 26, 1983, entitled i,An Act. to permit a Local SchooL naminis_t:rative Unit with ltore than70,000 Students to Extencl the

Prc>bationar:y periocl for I.Ion_

tenrr ::ecl Tr:;rche:cs .',

No Objec'tion

No Objection

No Objection

He.arsay, relevance ; ..

,

I"! seived on plaj.ntiffs,

f:. no objecri";;-;;aa!D

accurate . :

::' .'

a

:

ReI elt;11'1g'

-(,lr

Gingles

& Pugh

Number Title

46. Chart indicating current number

of blacks on the County Democratic

Party Executive Committee for

selelted counties. No objection

47. Letter from Kaye Gattis to James

Wallace , Jr. , 7-1.5-83. Hearsay, relevance

48. Artic}e from N. C. Insight entitledrThe Runoff Friilarl1-EEth to No objection with

Victory" by Mark tanier supporting witness

49. Editorial from Charlotte Observer, Untimely, hearsay,

2-4-82 opinion

50. t gditorial from Ralglgh Times, Untimely, hearsay,

! 7-15-83. # relevanle, opini6ir

testimony

-65- I

| ,t., iJ.i,.)

Objection

8. Deposition of William Mi1ls pages 4-5, and 24-29

C. Interrogatories

DefendanE's Response to Gingles' Plaintiff's First

Set of Interrogatories:

Document Portion Obi ections

None L-2LiL

#2 Memos of LZl28/70, ]-0/3172,

9/t2172 and ll7172

i7

tL2A

f19

i20

i2L

*27 "Patterns of Pay in N.C. State Foundation, hearsay,

GovernmenE and "Institutional opinion, reLevance

Racism/Sexism in N.C. State

Governmentt', only.

#31 "N.C. Housing Element - L972" Foundation, hearsay,

and Housing for North Carolina: opinion, reLevance

Policy and AcEion Recormnendations",

onlY

-76A-

Amended

Defendants! Witnesses (continued)

Name Address

20. Mark Lanier 1215 West Main St.

Carrboro, NC

275L0

2L. Malachi Greene 1820 Seigle Ave.

Charlotte, NC

28205

Proposed Testimonv

Establish foundation for

introduction of article,

"The Run off Primary A

Path to Victoxy ro

Defendantsr Exhibit 48,

and testify concerning

conclusions and analysis

in that article.

Establish the fact that

black people have fuI1

access to the political

process in t4ecklenburg County

and that they are able to

elect the candidates of

their choice.

NOTE: Plaintlffs obJect Eo the r:ntimely addiElon of Malachi

Green to defendants' list of witnesses.

-75b-

Amended

B.

DESIGNATIONS OF PLEADINGS

Pugh Plaintiffs may introduce at trial:

t. The complaint, the Ist amendeo complaint, the 2nd amenciedcomplaint and supplemental complaint, the answer to thecompraint. counsel intends to prove that the pugh plain-

tiffs qre a salient class of voters entitled to raise equalprotection claims as to the use of multimember and single

member districts.

2- The answers to pugh rnterrogatories rst set *1, 3, 4, L4,r9, 37, Exhibits ,c, and 'D'. counsel intends io provethat the Legislature adopted criteria for apporti6ninglegislative districts; that statements of legislltors madeggntemporaneously with the passage of N.G G.s. l2o-1 and120-2 evidence both a raciat ana non-racial desire togerrymande.r minority party voters and minority race votersthrough the use of large multimember distri6ts; that thecombination of multimember and single member districtsas provided for in N.c.G.s. r2o-r and Lzo-2 is not ration-a1ly related to a compelling state purpose or interest.

3. Affidavit of Theodore S. Arrington.

Counsel intends to Prove that a voter in a multimemberdistrict has a more than proportionate chance of affectingan election outcome than does a voter in a single membeidistrict through the use of weighted voting; inat rargemultimember districts tend to elect representatives tr5mcertain limited, socio-economic classes; that rarge multi-

member districts make it more difficult for a voter to selectfrom among the candidates compared to the ability of a single

member district voter; that candidates in large multimem6erdistricts have in order to have a chance of suicess must runlarger and costlier campaigns than candidates in single

member districts; that Pugh Plaintiffs votes are effected bythe use of such districts because citizens of multimembeidistricts have diminished aecess to the politica] pro"."iJthat candidates in large multimember distiicts are accounr-able to a larger number of constituents than in a single

member district; that voters in large multimember distriitsspecif ically in t{ake, Durham, }leck}enburg, and Forsyth countyhave in the past engaged in racial bloc voting

Deposition of Marshalr Rauch and Dan Li1Iey, Examination by

!1r . Hu nter.

counser intends to prove that the Legisrature was aware ofthe discriminatory effect of large murtimember districtsand the use of county lines in apportioning the senate and

House Districts; that statements of legislators made cont.emp-oraneously with the passage of N.G G.s. 120-1 and l2o-2evidence both a racial and non-rar:ial desire to gerrymander

minority party voters and minority race voters Cnrougtr theuse of large multiinember districls; that the. Legisrature

-77 -

Amended

4.

* Objections noted on page 78

could have taken into account the racial and political makeup of the murtimember districts; that there is a presumptionof discrimination in the use or murtimember districts whichnumer ically submerge minor.ity party voters and minorityracial voters; that tne combinuii6n of murtimenber and singlemember dist.rict_s- as provided for in N.c.G.s. 120_1 and l2o_2is not rationally related to a compelling state purpose orinterest.

6. Deposition of Frr. cohen, Examination by Mr. Hunter.

counsel intends to Prove that that the Legislature could havetaken into account the raciar and poriticar make up of themult imember districts.

Defendant I s Objections

with the loca1 rules in

forth their objections

Pugh Desiqnation

(Due to Pugh plaintiffs' failure to comply

formating its designations, defendants set

below:

Defendants' Objections

Object to the extent the defendants,

answers to Pugh interrogatories are

superseded Ey stipulations of counsel

in the Pre-trial Order.

Unsworn Affidavit, relevance,

conclusory, opinion.

-78-

Amended

#2

#3

c. Designation of Pleadlngs and Discovery Material s - -Def endant s

Obj ectionsDocu:nent

Deposition of Dan LiL1eY

Deposition of Marshall Rauch

Deposition of Gerry Cohen

Portion

Deposition of

Grady Hauser

Deposition of

MlI1s

Charles

Willian

At1

A11

P. 25,

P. 85,

P. 87,

p. 88,

P. 89,

P. 92,

P. 93,

p. 94,

P. 96,

P. 97,

P. 98,

P. 99,

P. 100,

p. 153,

p. 154,

AU.

A1_1

1. 5-22

L. L9-25 t

L.2-25t

1. 2-25t

1. 2-L5 t

L. 4-25;

1. 2-25t

L. 2-3t

L. L8-24i

1. 2-3i

1. 16-25it

1. 2-25 t1

1. 2-20i

l-. 13-25:r

1. 2-n;'t

Competence

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

Relevance,

Opinion Testimony

None

Relevance,

Opinion Testimony

Deposition Impro-

perly Taken Outside

Time for Dlscovery

Note:

Plaintiffs object to defendants'

the basis of Hearsay and Rule 32.

noted where appropriate.

use of aLL five deposi.tions

Additional objections are

-7 9-

Amended