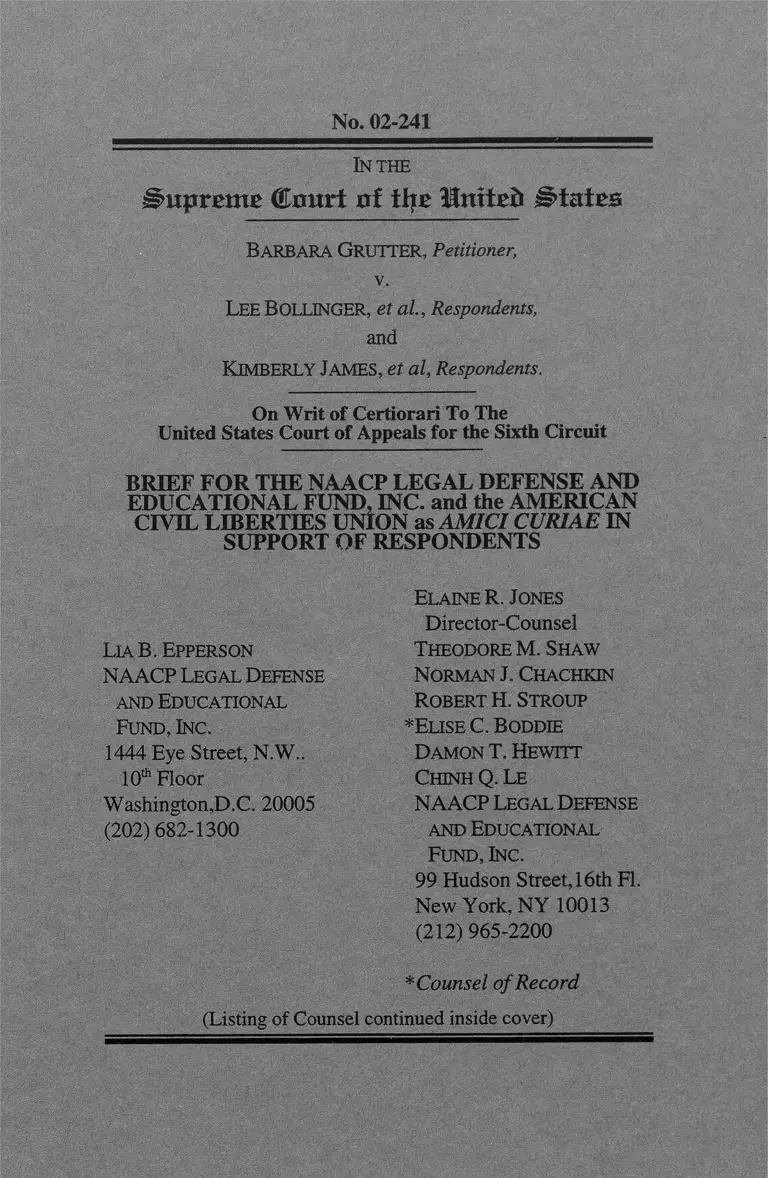

Grutter v. Bollinger Brief for the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. et al. as Amici Curiae in Support of Respondents

Public Court Documents

February 18, 2003

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Grutter v. Bollinger Brief for the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. et al. as Amici Curiae in Support of Respondents, 2003. 9c91cfe9-b49a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/dd490b41-4a72-4634-a9a7-cd114e0dea30/grutter-v-bollinger-brief-for-the-naacp-legal-defense-and-educational-fund-inc-et-al-as-amici-curiae-in-support-of-respondents. Accessed February 04, 2026.

Copied!

No. 02-241

In THE

Supreme Court of tfjo United States

B a r b a r a GRUTTER, Petitioner,

V.

LEE BOLLINGER, e t a l. , Respondents,

and

K im b e r l y Ja m e s , e t a l, Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari To The

United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

BRIEF FOR THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC. and the AMERICAN

CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION as AMICI CURIAE IN

SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS

E l a in e R. J o n es

Director-Counsel

T h e o d o r e M . S h a w

N o r m a n J. C h a c h k in

R o b e r t H . St r o u p

*E l is e C. B oddee

D a m o n T . H e w it t

C h in h Q. L e

NAACP Le g a l D e f e n s e

a n d E d u c a t io n a l

F u n d , In c .

99 Hudson Street, 16th FI.

New York, NY 10013

(212) 965-2200

* Counsel o f Record

(Listing of Counsel continued inside cover)

L i a B. E p p e r s o n

NAACP L e g a l D e f e n s e

a n d E d u c a t io n a l

Fu n d , In c .

1444 Eye Street, N.W..

10th Floor

Washington,D.C. 20005

(202)682-1300

(Listing of Counsel continued from cover)

O f Counsel:

St e p h e n R . S h a pir o

Legal Director

C h r is t o p h e r A . H a n s e n

E. V in c e n t W a r r e *

Am e r ic a n C iv il L iberties

U n io n F o u n d a t io n

125 Broad Street, 18th FI.

New York, NY 10004

(212) 529-250 *

Counsel fo r Amici Curiae

1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Table of Authorities ................................................................... ii

Interest of Amici .......................................................................... 1

Summary of Argument...............................................................1

ARGUMENT —

I. Race-Sensitive Admissions Policies Further the

Compelling Goals of Diminishing the Effects of

Deepening Racial Segregation and of

Preserving Opportunities in Higher Education

for African A m ericans............................ 3

n. Historical Racial Oppression by Governmental and

Private Actors and Ongoing Discrimination

Continue to Significantly to Affect the Lives and

Opportunities of African Americans ..........................6

A. Slavery and Jim Crow Constituted an

Unbroken Chain of Racial Oppression That

Remained Intact Until the Second Half of

theTwentieth C entury.......................................7

B. The Cumulative Effect of Generations of

Racial Subordination and Continued

Discrimination Has Produced Stark

Inequality Which, By Any Measure, Leaves

A frican A m ericans S ig n ifican tly

Disadvantaged ............... ......................... .. . 13

Page

TABLE OF CONTENTS (continued)

Page

HI. The Fourteenth Amendment Should Not Be

Interpreted to Frustrate Voluntary State Efforts,

Using Race-Conscious Remedies, to Eliminate

the Continuing Effects of State-Sponsored

Discrimination ...........................................................22

A. The Persistence of Pervasive Racial

Inequality Calls For the Court to Revisit its

Conclusion in Bakke That Redressing

“Societal Discrimination” Is Not A

Compelling In te re s t....................... 24

B. A Principal Purpose of the Fourteenth

Amendment Was to Constitutionalize

Race-Conscious Remedies ............................ 29

C onclusion.......................................................... 30

Appendix “A” — Legislative History of Freedmen’s

Bureau Acts and Similar

Legislation................... la

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Adams v. Richardson,

480 F.2d 1159 (D.C. Cir. 1973) ..................................... 10

Adarand Constructors, Inc. v. Pena,

515 U.S. 200(1995) ................. . . . 2 7

Ill

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (continued)

Page

Cases (continued):

Board ofEduc. o f Okla. City v. Dowell,

498 U.S. 237 (1991)..................................... 4 ,26 ,2 7

Beerv. United States,

425 U.S. 130 (1976)................................................. 17

Belkv. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. ofEduc.,

269 F.3d 305 (4th Cir. 2 0 0 1 )................................ .2 6

Brown v. Board o f Education,

347 U.S. 483 (1954)..................................... 10, 16, 27

City o f Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co.,

488 U.S. 469 (1989).............................. 23, 25, 27, 28

Civil Rights Cases,

109 U.S. 3 (1883)........................................................ 9

Cooper v. Aaron,

358 U.S. 1 (1958)..................................................... 27

Dred Scott v. Sandford,

60 U.S. (19 How.) 393 (1 8 5 7 ).................................. 7

Freeman v. Pitts,

503 U.S. 467 (1992) 4, 26, 28

IV

Cases (continued):

Georgia v. Ashcroft,

195 F. Supp. 2d 25 (D.D.C. 2002),

prob. juris, noted, 71 U.S.L.W. 3486,

2003 D.A.R. 698 (U.S. 2003) .............................. .1 7

Groves v. Slaughter,

40 U.S. (15 Pet.) 449 (1841) ................................ . . 7

Grutter v. Bollinger,

288 F.3d 732 (2002).................................................. 28

Hazelwood Sch. Dist. v. United States,

433 U.S. 299 (1977).................................................. 22

Holmes v. Danner,

191 F. Supp. 394 (M.D. Ga. 1961) ........................27

Johnson v. Transp. Agency,

480 U.S. 616(1987).................................................. 22

Knight v. Alabama,

14 F.3d 1534 (11th Cir. 1 9 9 4 )................... ............. 27

Manning v. Sch. Bd. o f Hillsborough County,

244 F.3d 927 (11th Cir. 2 0 0 1 ) ................................. 26

Miller v. Johnson,

515 U.S. 900(1995)......................................................4

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (continued)

Page

V

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (continued)

Page

Cases (continued):

Milliken v. Bradley,

418 U.S. 717 (1974)....................................... 4, 10, 26

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada,

305 U.S.337 (1938) .................................................. 10

Missouri v. Jenkins,

515 U.S. 70 (1995)....................................... 4, 26

Moore v. Illinois,

55 U.S. (14 How.) 13 (1 8 5 2 )............................ .. 7

Pasadena City Bd. ofEduc. v. Spangler,

427 U.S. 424 (1976)................. ................................ 26

Personnel Admin'r o f Mass. v. Feeney,

442 U.S. 256(1979).................................................. 26

Plessy v. Ferguson,

163 U.S. 537 (1896)............................................. 9 ,22

Prigg v. Pennsylvania,

41 U.S. (16 Pet.) 539(1842).......................................7

Regents o f the Univ. o f Cal. v. Bakke,

438 U.S. 265 (1978)........................................... passim

Roberts v. City o f Boston,

59 Mass. (5 Cush.) 198 (1 8 5 0 ).................................... 7

VI

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (continued)

Page

Cases (continued):

San Antonio Indep. Sch. Dist. v. Rodriguez,

411 U.S. 1 (1973)......................... ..................... 10,26

Shaw v. Reno,

509 U.S. 630 (1993)....................................................4

Shelley v. Kraemer,

334 U.S. 1 (1948) ............... ................................ 11

Sipuel v. Okla. State Regents,

332 U.S. 631 (1948)................................................. 10

South Carolina v. Katzenbach,

383 U.S. 301 (1966)................................................. 17

Sweatt v. Painter,

339 U.S. 629(1950)............................................. 6, 10

United States v. Fordice,

505 U.S. 717 (1992)................................................ 27

Village o f Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan

Hous. Auth., 429 U.S. 252 (1977) .......................... 26

Washington v. Davis,

426 U.S. 229 (1976)................................................. 26

vn

Cases (continued):

Wygant v. Jackson Bd. o f Educ.,

476 U.S. 274 (1986)................................ .... 23, 25, 27

Constitution:

U.S. Const, art. I, § 9 ................................................................ 7

U.S. Const, art. IV, § 2 .............................................................. 7

U.S. Const, art. IV § 4, art. I, § 8 ..............................................7

U.S. Const, amends. XE3, XIV, XV ......................... 7

Statutes:

Act of March 3, 1865, c.90, 13 Stat. 507-508 ................... 29

1866 Freedmen's Bureau Act, Act of July 16,

1866, c. 200, 14 Stat. 173-177 ................... 29, la, 2a

14 Stat. Res. 86 (1866).......................................................... 2a

1867 Colored Servicemen's Claims Act, 15

Stat. 26, Res. 25 .................................................. 29-30

15 Stat. Res. 4 (1867)............................................................ 2a

15 Stat. Res. 28 (1867).......................................................... 2a

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (continued)

Page

Vlll

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (continued)

Page

Statutes (continued):

Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C. § 1973 (2002) . . . . 17

Legislative Materials:

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. .................... 30, la, 2a

H.R. Rep. No. 196, 94th Cong., 1st Sess. 57-58 (1975) . . 17

Other Authorities:

Richard D. Alba et al., How Segregated are Middle-

Class African Americans? 47 Soc. Probs.

543 (2000) ................................................................. 15

T. Alexander Aleinikoff, A Case for Race-

Consciousness, 91 Colum. L. Rev. 1060 (1991) . . . 8

James Allen et al., Without Sanctuary (2 0 0 0 )...................... 8

Alfred Avins, The Reconstruction Amendments’

Debates (rev. ed. 1974) ........................................... 29

Marianne Bertrand & Sendhil Mullainathan, Are

Emily and Brendan More Employable

than Lakisha and Jamal? A Field Experiment

on Labor Market Discrimination (2002) . . . . 19

IX

Other Authorities (continued):

Alfred W. Blumrosen & Ruth G. Blumrosen, The

Reality of Intentional Job Discrimination in

Metropolitan America— 1999 (1999) .................... 18

Jomills Henry Braddock II & James M. McPartland,

How Minorities Continue to be Excluded

from Equal Employment Opportunities,

43 J. of Soc. Issues 27 (1987) ................................ 18

Calvin Bradford, Center for Community Change,

Risk or Race? Racial Disparities and the

SubPrime Refinance Market (2002) ...................... 13

William G. Bowen & Derek Bok, The Shape of

the River (1 9 9 8 )............................................................ 5

Mitchell J. Chang, The Positive Educational

Effects of Racial Diversity on Campus,

in Diversity Challenged (Gary Orfield

and Michael Kurlaender eds., 2001) ..................... 5

Camille Zubrinsky Charles, Socioeconomic Status

and Segregation: African Americans,

Hispanics and Asians in Los Angeles,

in Problem of the Century (Elijah Anderson

& Douglas S. Massey eds., 2001) .......................... 14

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (continued)

Page

X

Other Authorities (continued):

Civil Rights Project, Harvard U. & Lewis Mumford

Ctr. For Comparative Urban & Regional

Research, State U. of New York at Albany,

Housing Segregation (2001) .......................... 11

Sharon M. Collins, Blacks on the Bubble, 34 Soc.

Q. 429 (1993) ............................................................. 19

Sharon M. Collins, The Marginalization of Black

Executives, 36 Soc. Probs. 317 (1989) ................. 19

Joseph Dalaker, U.S. Census Bureau, Poverty in

the United States, 2000 (2001)................................ 20

Nancy A. Denton, The Persistence of Segregation:

Links Between Residential Segregation and

School Segregation, 80 Minn. L. Rev. 795

(1996) ..................................... 10

Marlese Durr & John R. Logan, Racial Submarkets

in Government Employment, 12 Soc. F.

353 (1997) ................................................................. 19

Equal Employment Advisory Council, Amicus

Curiae Brief in Support of Neither Party

in Grutter v. Bollinger (No. 02-241) .......................... 5

Horace E. Flack, The Adoption of the Fourteenth

Amendment (1908) .................................................. 29

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (continued)

Page

XI

Other Authorities (continued):

Barbara J. Flagg, “Was Blind, But Now I See,”

91 Mich. L. Rev. 953 (1993) ................................. .2 3

Erica Frankenberg et al., Harvard U., A Multiracial

Society with Segregated Schools (2 0 0 3 )......... 10,16

Erica Frankenberg & Chungmei Lee, Harvard U.,

Race in American Public Schools (2002) ............... 4

John Hope Franklin & Alfred A. Moss, Jr., From

Slavery to Freedom (6th ed. 1988) ...................... 8 ,10

Ralph Ginzburg, 100 Years of Lynchings (1988) ............. .. 8

Roxane Harvey Gudeman, Faculty Experience with

Diversity, in Diversity Challenged (Gary Orfield

and Michael Kurlaender eds., 2001)...........................5

Cheryl I. Harris, Whiteness as Property, 106 Harv.

L. Rev. 1707 (1993)........................................... 23,27

A. Leon Higginbotham, Shades of Freedom (1996) . . . . 8, 9

Arnold Hirsch, Making the Second Ghetto

(2d ed. 1998)........................ ...................................... 12

Harry J. Holzer, Race Differences in Labor Market

Outcomes Among Men, in 2 America

Becoming (Neil J. Smelser et al. eds., 2 0 0 1 )......... 18

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (continued)

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (continued)

Page

Other Authorities (continued):

Harry J. Holzer & Keith R. Ihlanfeldt, Customer

Discrimination and Employment Outcomes for

Minority Workers, 113 Q. J. of Econ. 835(1998). 18

John Iceland, et al., U.S. Census Bureau, Racial and

Ethnic Segregation in the United States: 1980-

2000(2002) ....................................... ....................... 14

Kenneth T. Jackson, Crabgrass Frontier (1985) ............... 11

Richard Kluger, Simple Justice (1975) ............................. 7, 8

Stanley Lieberson, A Piece of the Pie (1980) ................. .... 8

John R. Logan & Brian J. Stults, Racial Differences in

Exposure to Crime: The City and Suburbs of

Cleveland in 1990, 37 Criminology 251 (1999) . . 15

Joseph Lupton & Frank Stafford, Household Financial

Wealth, (Thousands of 1999 Dollars), Institute

for Social Research (Jan. 2000) ............................... 20

Janice F. Madden, Do Racial Composition and

Segregation Affect Economic Outcomes in

Metropolitan Areas? in Problem of the

Century (Elijah Anderson & Douglas S.

Massey eds., 2001 ).................................................... 21

X lll

Other Authorities (continued):

Manning Marable, The Great Walls of Democracy

(2002) ......................................................................... 16

George S. Masnick, Harvard U., Home Ownership

Trends and Racial Inequality in the United

States in the Twentieth Century (2 0 0 1 )................. 15

Douglas S. Massey & Nancy A. Denton, American

Apartheid (1993) ...................................................... 14

Douglas S. Massey & Mary J. Fischer, Does Rising

Income Bring Integration? New Results for

Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians in 1990, 28

Soc. Sci. Res. 316(1999) ......................................... 14

Messages and Papers of the Presidents, vol.

vm (1914) ........................................................ App. 2a

Ronald B. Mincy, The Urban Institute Audit Studies,

in Clear and Convincing Evidence (Michael

Fix & Raymond J. Struyk, eds. 1993) ........... .18

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

Brief as Amicus Curiae in B a kke .......................... 29

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (continued)

Page

XIV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (continued)

Page

Other Authorities (continued):

National Center for Health Statistics, Department of

Health and Human Services Table 23,Infant

Mortality Rates, Fetal Mortality Rates, and

Perinatal Mortality Rates, According to Race

(2001) ...................................................................................21

Office of Employment and Unemployment Statistics,

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Table A-19,

Usual Weekly Earnings of Employed Full-Time

Wage and Salary Workers by Occupation, Sex,

Race and Hispanic Origin, 2002 Annual Averages

(2003)......................................................................... 18

Gary Orfield, The Growth of Segregation, in Dismantling

Desegregation (Gary Orfield et al. eds., 1996) . . . 17

Gary Orfield, Harvard U., Schools More Separate (2001). 14

Gary Orfield, Segregated Housing and School

Resegregation, in Dismantling Desegregation

(Gary Orfield et al. eds., 1996) .................. 11, 12, 16

Gary Orfield & Dean Whitla, Diversity in Legal

Education, in Diversity Challenged (Gary

Orfield and Michael Kurlaender eds., 2 0 0 1 ) ...........6

Mary Pattillo-McCoy, Black Picket Fences

(1999)................................ ............ .. 14, 19, 20

XV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (continued)

Page

Other Authorities (continued):

Benjamin Quarles, The Negro in the Making of

American History (3d ed. 1987)...................................7

Franklin Raines, What Equality Would Look Like,

in The State of Black America 2002 (Lee A.

Daniels, ed.) (2 0 0 2 ).................................................. 22

David R. Roediger, The Wages of Whiteness

(rev. ed. 1999) ..................... 8

Eric Schnapper, Affirmative Action and the

Legislative History of the Fourteenth

Amendment, 61 Va. L. Rev. 753

(1985) ................................................. 29, 30, App. 2a

Brian D. Smedley et al., Institute of Medicine of the

Nat’l Academies, Unequal Treatment (2003) . 20-21

Thomas J. Sugrue, Expert Report, Grutter v. Bollinger,

No. 97-75321 (E.D. Mich. December 15,

1998) ............................................................ 11, 12, 15

Cass R. Sunstein, The AntiCaste Principle, 92 Mich.

L. Rev. 2410 (1994)................................................. 28

Jacobus tenBroek, Equal Under Law (rev. ed. 1965) . . . . 29

Melvin E. Thomas et al., Discrimination Over the Life

Course 41 Soc. Probs. 608 (1994) ................. 19

XVI

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (continued)

Page

Other Authorities (continued):

Melvin E. Thomas, Race, Class, and Personal

Income, 40 Soc. Probs. 328 (1993) ........................ 19

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Table A-2,

Employment Status of the Civilian Population

by Race, Sex and Age (2003)................................... 18

Leland Ware & Antoine Allen, The Geography of

Discrimination: Hypersegregation, Isolation and

Fragmentation Within the African-American

Community, in The State of Black America

(2002) ................................................................. 15, 16

George Wilson et al., Reaching the Top: Racial

Differences in Mobility Paths to Upper-Tier

Occupations, 26 Work & Occupations (1999) . . . . 19

BRIEF OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC. AND THE AMERICAN

CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION AS AMICI CURIAE

IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS*

Interest of Amici

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

(“LDF”) is a non-profit corporation established under the laws

of the State of New York. It was formed to assist black persons

in securing their constitutional rights through the prosecution

of lawsuits and to provide legal services to blacks suffering

injustice by reason of racial discrimination. For six decades,

LDF attorneys have represented parties in litigation before this

Court and the lower courts involving race discrimination and

various areas of affirmative action. LDF believes that its

experience in and knowledge gained from such litigation will

assist the Court in this case.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) is a

nationwide, nonprofit, nonpartisan organization with more than

300,000 members dedicated to the principles of liberty and

equality embodied in the Constitution. Since its founding in

1920, the ACLU has played an active role in the battle for

racial justice and has long supported the constitutionality of

affirmative action in appropriate circumstances, including filing

a brief as amicus curiae in Regents o f the Univ. o f Cal. v.

Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978).

Summary of Argument

This country has journeyed a long and painful road toward

racial integration that this case now threatens to destroy. For

many African Americans, the force of this nation’s sordid and

‘Letters of consent by the parties to the filing of this brief have been

lodged with the Clerk of this Court. Amici are counsel for defendant-

intervenors in the companion case, Gratz v. Bollinger. No counsel for any

party in Grutter v. Bollinger authored this brief in whole or in part, and no

person or entity, other than amici, made any monetary contribution to its

preparation.

2

all too recent history of apartheid still blocks their path. If there

is any hope for this country to continue to make racial progress,

it lies, at least in part, in the unique ability of colleges and

universities to bring together persons of all racial backgrounds

to achieve the educational benefits of diversity and, ultimately,

to create a more just, racially integrated society.

More than 300 years of slavery, segregation, and invidious

discrimination by public and private actors have produced a

systemic racial hierarchy that continues to this day. Numerous

studies document continuing widespread racial inequality in

virtually every aspect of our society, including education,

employment, income, housing, health care, life expectancy,

criminal justice, and in the accumulation of wealth. These

studies demonstrate the impact that race has in molding the

opportunities, experiences, and outlook of the overwhelming

majority of African Americans, including the black middle

class. The impact of race stretches across all economic strata

and extends even to those arguably best positioned to capture

the benefits of race-neutral policies. While class is an

important factor in accounting for opportunity, it is

demonstrably incorrect at this relatively early stage in our

country’s progress on race to assert that class alone uniquely

shapes economic, social, and political opportunity in this

country. In short, race matters, significantly — not because it

should, but because it does.

Yet the Court’s jurisprudence, including notably its

discussion of “societal discrimination” in Bakke,1 has cast a pall

over the ability of state and local actors to remedy voluntarily

the powerful imprint of racial discrimination on our society.

The Court’s affirmative action cases refer only in passing, if at

all, to our country’s undeniable and tragic history of racial

oppression. The cumulative, inter-generational consequences

of such racial subordination are dismissed as mere “societal

1Regents o f the Univ. o f Cal. v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978).

3

discrimination,” for which no institutional actor may be held

accountable, even those that have been complicit in

perpetuating racial disadvantage.

A principal objective of the Fourteenth Amendment was to

mitigate the enormous burdens of African Americans emerging

from slavery. It is a perversion of its purpose to prohibit

modest state efforts, such as the University of Michigan Law

School’s admissions program, to redress systemic racial

inequity.

ARGUMENT

It is because o f a legacy o f unequal treatment that

we now must permit the institutions o f this society

to give consideration to race in making decisions

about who will hold the positions o f influence,

affluence, and prestige in America. For fa r too

long, the doors to those positions have been shut to

Negroes. I f we are ever to become a fully

integrated society, one in which the color o f a

person’s skin will not determine the opportunities

available to him or her, we must be willing to take

steps to open those doors. I do not believe that

anyone can truly look into America’s past and still

fin d that a remedy fo r the effects o f that past is

impermissible.

Justice Thurgood Marshall, in his Bakke dissent2

I. Race-Sensitive Admissions Policies Further the

Compelling Goals of Diminishing the Effects of

Deepening Racial Segregation and of Preserving

Opportunities in Higher Education for African

Americans

Racial segregation and isolation continue to be a menace in

243 8 U.S. at 401-02.

4

this society, producing and perpetuating sharp disparities in the

quality of life and opportunities for advancement of African

Americans. Their manifestation in the continued scourge of

residential segregation leaves institutions of higher education

as one of the few venues for meaningful cross-racial

interaction.3

In the context of primary and secondary schools, this Court

has already all but abandoned the judicial task of requiring

school districts to remedy racial segregation, severely limiting

the circumstances, means, and duration of desegregation

remedies. See e.g., Missouri v. Jenkins, 515 U.S. 70 (1995);

Freeman v. Pitts, 503 U.S. 467 (1992); l3d. ofEduc. o f Okla.

City v. Dowell, 498 U.S. 237 (1991); Milliken v. Bradley, 418

U.S. 717 (1974). Even in so doing, however, it has

acknowledged that “the potential for discrimination and racial

hostility is still present in our country, and its manifestations

may emerge in new and subtle forms after the effects of de jure

segregation have been eliminated.” Freeman, 502 U.S. at 490.

Voluntary race-conscious admissions policies by colleges

and universities remain one of the sole avenues for seeking to

mitigate the stubborn vestiges of past wrongs, ameliorating the

effects of ongoing discrimination, and increasing the

participation of all members of our society. Indeed, this Court,

in Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S. 630 (1993), stated that our

Constitution encourages us to weld together various racial and

ethnic communities, and to avoid the racial balkanization that

has plagued other nations. Id. at 648-49. See also Miller v.

Johnson, 515 U.S. 900,911 (1995). Race-sensitive admissions

policies strive to do just that by fostering racial integration in

our nation’s schools and interaction between individuals from

3See generally ERICA FRANKENBERG & CHUNGMEI Lee , HARVARD U.,

Race in American Public Schools (2002), available at

http://www.civilrightsproiect.harvard.edu/research/deseg/reseg schoolsO

2.php.

http://www.civilrightsproiect

5

diverse backgrounds.

Indeed, studies show that meaningful cross-racial interaction

in institutions of higher learning has significant social and

educational benefits. The more racially diverse a student body,

the more likely that students will socialize across racial lines

and talk about racial matters.4 These interactions have a

positive impact on student retention, overall college

satisfaction, and intellectual and social self-confidence among

all students.5 Faculty have also reported that racial and ethnic

diversity in the classroom helps students broaden the sharing of

experiences, raise new issues and perspectives, confront

stereotypes relevant to social and political issues, and gain

exposure to perspectives with which they disagree or do not

understand.6

This Court noted over fifty years ago that law school

provides a particularly important environment for meaningful

cross-racial interaction:

The law school, the proving ground for legal learning and

practice, cannot be effective in isolation from the

individuals and institutions with which the law interacts.

Few students and no one who has practiced law would

choose to study in an academic vacuum, removed from the

ASee, e.g., Mitchell J. Chang, The Positive Educational Effects o f Racial

Diversity on Campus, in DIVERSITY CHALLENGED 175, 183 (Gary Orfield

and Michael Kurlaender eds., 2001). See also W illiam G. Bowen &

Derek Bok , The Shape of the River 232 (1998) (56% of white

matriculants and 88% of black matriculants of selective colleges and

universities who enrolled in 1989 indicated that they “knew well” two or

more classmates of the other race).

5See Chang, supra n. 4.

6Roxane Harvey Gudeman, Faculty Experience with Diversity, in

Diversity Challenged supra n. 4, at 251, 271. See also Brief Amicus

Curiae of the Equal Employment Advisory Council in Support of Neither

Party, Grutter v. Bollinger (No. 02-241).

6

interplay of ideas and the exchange of views in which the

law is concerned.

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629, 634 (1950). Given the deep

racial isolation that still exists in our society, such exchange of

views between individuals of diverse racial and ethnic

backgrounds is a critical life tool for all students.7

In the absence of other means for redressing systemic racial

disparity, Justice Powell’s opinion in Bakke has been crucial to

opening up opportunity for African Americans and other racial

minorities, in a way that has helped begin to create a pipeline

of racially diverse leaders and has fostered the fuller

participation of previously dispossessed segments of our

society. It is critical that colleges and universities retain the

limited ability to rely on race, not only to achieve the

educational benefits of diversity but also so that such

institutions may continue the long road toward a more just and

equitable society.

II. Historical Racial Oppression by Governmental and

Private Actors and Ongoing Discrimination Continue

To Affect Significantly the Lives and Opportunities of

African Americans

Any meaningful evaluation of the need for race-sensitive

admissions policies at the University of Michigan or at any

other college or university must first take account of the central

role that slavery, racial segregation, and systematic racial

oppression by public and private actors have played in

depriving generations of African Americans of social, political,

and economic opportunity, while concurrently according

profound advantages to whites.

’White students have been found to have a particularly enriching

experience, since they are so likely to have grown up with little interracial

contact. Gary Orfield & Dean Whitla, Diversity in Legal Education, in

Diversity Challenged supra n. 4, at 143,172.

7

A. Slavery and Jim Crow Constituted An Unbroken Chain

of Racial Oppression That Remained Intact Until the

Second Half o f the Twentieth Century

From the framing of the Constitution, governmental and

private actors legitimized and strengthened a system of

apartheid that enslaved African Americans.8 The original

Constitution sanctioned and preserved the institution of

slavery;9 Congress passed laws that bolstered slavery;10 and

federal and state courts perpetuated the subjugation and

dehumanization of even free blacks through decisions that

concretized racial oppression.11 The most abhorrent of these

cases was Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. (19 How.) 393

(1857), which eviscerated any real distinctions between slaves

and free blacks.12

sSee, e.g., Richard Kluger, Simple justice 27-28 (1975).

9See U.S. CONST, art. I, § 9 (providing for the importation of slaves until

at least 1808); U.S. CONST, art. IV, § 2 (capture and return of slaves to their

masters); U.S. CONST, art. IV § 4, art. I, § 8 (suppression of slave

rebellions); U.S. CONST, art. I, § 9 (barring taxes on exports produced by

slaves); U.S. CONST, art. I, § 2 (treating slaves as three-fifths of a person),

generally amended by U.S. CONST, amends. XIII, XIV, XV.

10The Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 empowered the federal government

to apprehend fugitives. See, e.g., BENJAMIN QUARLES, THE NEGRO IN THE

Making of American History 107 (3d ed. 1987). In most Southern states,

free blacks could not hold public office, vote, testify against a white person,

use a firearm, freely assemble, or travel freely between the states. Id. at 87-

88 .

nSee, e.g., Moore v. Illinois, 55 U.S. (14 How.) 13 (1852); Prigg v.

Pennsylvania, 41 U.S. (16 Pet.) 539 (1842); Groves v. Slaughter, 40 U.S.

(15 Pet.) 449 Roberts v. City of Boston, 59 Mass. (5 Cush.) 198,206

(1850).

i2A11 blacks were “regarded as beings of an inferior order. . . altogether

unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations;

and so far inferior, that they had no rights which the white man was bound

to respect.. . . ” 60 U.S. (19 How.) at 407.

8

Even after the abolition of slavery and the ratification of the

Fourteenth Amendment in 1868, public and private actors

maintained a strict racial caste system that subjugated African

Americans in every way.13 The Hayes-Tilden Compromise of

1877, which authorized the withdrawal of federal protection of

former slaves,14 removed the last obstacle to reinstating a

system of white supremacy in the South. Southern whites

embarked upon widespread lynching and terrorism against

blacks,15 and a campaign of voter intimidation denied blacks

the right to have any voice in the political process.16 State

legislatures approved voting requirements specifically designed

to eliminate the black vote, such as poll taxes and literacy

13In the American racial hierarchy, blacks have long endured a

particularly virulent form of antagonism and persecution unmatched by other

racial and ethnic groups. See, e.g, David R. Roediger, The W ages of

W hiteness 14 (rev. ed. 1999) ([T]he white working class, disciplined and

made anxious by fear of dependency, began. . . to construct an image of the

Black population as ‘other’—as embodying the preindustrial, erotic, careless

style of life the white worker hated and longed for.”); STANLEY LlEBERSON,

A Piece of THE P ie (1980) (focusing on particular hardships blacks faced

compared to white ethnics); T. Alexander Aleinikoff, A Case fo r Race-

Consciousness, 91 Colum . L. Rev . 1060, 1124 (1991) (“[W]hen the

ingenious American devices for excluding blacks from society are

contrasted with the assimilationist welcome accorded immigrants, one can

quickly . . . formulate a sensible answer to the question that lies deep in

many white minds: why can’t blacks do what my immigrant ancestors

did?”).

lASee A. Leon Higginbotham, Shades of Freedom 91- 93 (1996).

15From 1884-1900, there were over 2,500 lynchings, the great majority,

blacks in the South. See, e.g., John Hope Franklin & Alfred A. Moss,

Jr., From Slavery to Freedom 282 (6th ed. 1988); see also generally

Ralph Ginzburg, 100 Years of Lynchings (1988); James Allen, et al„

W ithout Sanctuary (2000).

16See, e.g., KLUGER, supra n. 8, at 59-60.

9

tests.17 Consequently, blacks lacked the power to vote out the

very governments that imposed the rigid hegemonic system that

denied them resources and full citizenship.

A series of decisions by this Court ratified the denial to

blacks of the rights of full citizenship. In the Civil Rights

Cases, 109 U.S. 3 (1883), the Court declared unconstitutional

the Civil Rights Act of 1875, which had outlawed racial

segregation in public accommodations. After more than two

hundred years of systemic white supremacy, in which

governmental resources had been routinely employed to

perpetuate the institution of slavery, the Court held that any

remedy for racial injustice was beyond Congress’s power.18 In

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896), this Court delivered

the implicit deathblow to the civil rights of African Americans,

with the “separate but equal” doctrine. This paved the way for

the extension of white supremacy to all areas of social life,

particularly education.

By 1900, every Southern state had enacted laws requiring

separate schools for blacks and whites. As blacks migrated to

the North in the first part of the twentieth century, they were

"H igginbotham, supra n. 14, at 174(1996). As one Mississippi judge

candidly commented, “there has not been a full vote and a fair count in

Mississippi since 1875... we have been preserving the ascendancy of white

people b y . . . stuffing the ballot boxes, permitting perjury and . . . carrying

the elections by fraud and violence.” Id.

18In language that resembles some of this Court’s modern affirmative

action jurisprudence, the Court observed:

When a man has emerged from slavery, and by the aid of beneficent

legislation has shaken off the inseparable concomitants of that state,

there must be some stage in the progress of his elevation when he takes

the rank of a mere citizen, and ceases to be the special favorite of the

laws, and when his rights as a citizen, or a man, are to be protected in

the ordinary modes by which other men’s rights are protected.

109 U.S. at 25.

10

urged, if not forced, to attend segregated schools. Indeed, for

the first half of the twentieth century, the majority of African-

American children were confined to impoverished, short-term

schools. By 1930, $7 was spent for whites to every $2 spent for

blacks.19 These separate and unequal schools helped to

perpetuate the mythology of white supremacy and paralyzed

any hope of black advancement.

In higher education, the disingenuous creed of “separate but

equal” restricted blacks to segregated institutions. See Sweatt,

339 U.S. 629; Sipuel v. Okla. State Regents, 332 U.S. 631

(1948); Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337

(1938). It was not until Brown v. Board o f Education, 347U.S.

483 (1954), decided two generations later, that this Court really

began to undo this nation’s sordid history of racial oppression.

Even after this momentous decision, however, it would be

years before many of this nation’s elementary and secondary

schools and colleges would readily open their doors to African

Americans.20

Meanwhile, both before and after Brown, the federal

government carried out a series of policies that created and

19Frankun & Moss, supra n. 15, at 361-62.

20Until the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, the Executive Branch

had no power to enforce Brown’s mandate for school desegregation. By

1969, the federal government virtually ceased to exercise that power, once

again leaving the responsibility for constitutional compliance to the courts.

Cfi Adams v. Richardson, 480 F.2d 1159, 1164-65 (D.C. Cir. 1973)

(observing the Executive Branch’s considerable delay in enforcing the

desegregation of higher learning institutions through Title VI). This Court’s

rulings rejecting metropolitan desegregation in Milliken, 418 U.S. 717, and

financial equalization of schools in San Antonio Indep. Sch. Dist. v.

Rodriguez, 411 U.S. 1 (1973), sharply restricted judicial authority as well.

Erica Frankenberg et al„ Harvard U„ A Multiracial Society with

S e g r e g a t e d S c h o o l s 8 ( 2 0 0 3 ) , a v a i l a b l e a t

h t tp : / /www .c iv i l r i gh t spr o jec t .harva rd .edu /r es ea rch/ re seg03/

AreWeLosingtheDream.pdf.

http://www.civilrightsproject.harvard.edu/research/reseg03/

11

perpetuated a system of residential segregation, the effects of

which are still manifest today.21 Starting with the New Deal,

“federal housing policies translated private discrimination into

public policy”22 and officially endorsed the discriminatory

practices of real estate developers, banks, mortgage brokers,

appraisers, and insurance agents.23 Blacks were confined to

overcrowded, overpriced, and deteriorating “ghettos” whose

inferior services included inadequate, segregated schools.24

Many black communities were completely isolated by an iron

curtain of legally enforceable covenants on all sides, which

created massive overcrowding, a “race tax” on housing prices,

and deterioration of housing within predominantly black

neighborhoods.25 The sorry legacy of these policies persists

long after the enactment of fair housing laws, as fears of the

“black ghetto” contribute to racial discrimination and flight

from integrated neighborhoods.26

21 See Nancy A. Denton, The Persistence o f Segregation: Links Between

Residential Segregation and School Segregation, 80 MINN, L. Rev . 795,

801-06 (1996).

22 See Expert Report of Thomas J. Sugrue, Grutter v. Bollinger, No. 97-

75321 (E.D. Mich. December 15, 1998) at 27.

22See generally KENNETH T. JACKSON, CRABGRASS FRONTIER 196-218

(1985).

2iSee, e.g., Civil Rights Project, Harvard U. & Lewis M umford

Ctr. For Comparative Urban & Regional Research, State U. ofNew

York at Albany, Housing Segregation 2-4 (2001), available at

http:ZAvww.civiMghtsproject.harvard.edu/research/metro/callJhousinggar

y.php; Gary Orfield, Segregated Housing and School Resegregation, in

Dismantling Desegregation 291, 304-330 (Gary Orfield et al. eds.,

1996).

250rfield, supra n. 24, at 304.

26Civil Rights Project & Lewis Mumford Ctr ., supra n. 24, at 2.

Even after this Court outlawed restrictive covenants in Shelley v. Kraemer,

334 U.S. 1 (1948), the FHA Underwriting Manual cautioned against the

12

Through the 1960s, federal “urban renewal” strategies

devastated black neighborhoods and pushed blacks further into

racially isolated, economically depressed areas.27 “Slum

clearance” leveled black communities to produce new

developments near downtown areas, and displaced black

families into segregated housing markets. This has created new

isolated pockets of poverty, reinforced racial ignorance and

hostility against blacks, and set in motion a catastrophic

economic avalanche that further circumscribed blacks’ access

to capital. The federal government’s calculated involvement in

these discriminatory housing policies not only reinforced

already established patterns of racial isolation and subjugation,

it lent them “a permanence never before seen” that “virtually

constituted a new form of de jure segregation”28 and

contributed to the existing racial isolation in this country’s

schools.

Predominantly black or mixed-race neighborhoods seldom

received federal mortgages and loan guarantees, a practice that

continued into the 1970s. To this day, private banks patterned

their lending policies after the FHA’s discriminatory practices,

which extended the reach of such practices deep into the private

sector.29 Private banks continue to prey on African American

homeowners through “reverse redlining” practices that offer

excessive loans at exorbitant fees. This has the effect of further

introduction of “incompatible” groups into a neighborhood and encouraged

appraisers to rely on physical barriers to guarantee the separation of whites

and blacks. See, e.g., Orfield, supra n. 24, at 305; Sugrue, supra n. 22, at

27. These federal policies paved the way for violent assaults — including

stone throwing, vandalism, arson, and physical attacks — on blacks who

moved into white neighborhoods. Sugrue, supra n. 22, at 28.

270rfield, supra n. 24, at 305-06.

28 ARNOLD HlRSCH, MAKING THE SECOND GHETTO 254-55 (2d ed. 1998).

29See, e.g., Sugrue, supra n. 22, at 27-28.

13

destabilizing black neighborhoods and impeding black

economic development.30

These systemic government actions, in concert with

discriminatory private behavior, continued to deny equal

opportunity to African Americans. The combined force of

public and private discrimination for more than 300 years has

had a devastating impact on all aspects of black social,

educational, political, and economic opportunity in America.

B. The Cumulative Effect of Generations of Racial

Subordination and Continued Discrimination Has

Produced Stark Inequality Which, By Any Measure,

Leaves African Americans Significantly Disadvantaged

Race remains the critical dividing line in American society.

More than 300 years of calculated and profound racial

persecution by public and private actors have produced an

entrenched racial hierarchy that pervades every facet of life in

this country. Twenty-five years after the Court ruled in Bakke

that race-conscious admissions policies were constitutionally

permissible, some African Americans have made significant

progress as a result of opportunities that were once denied.

Nevertheless, widespread racial inequality remains a

fundamental fact of American life, including for the current

generation of college, graduate, and professional school

applicants who have grown up in a deeply racially fragmented

society. Until race ceases to be the barometer of economic,

social, and political opportunity, it will continue to be an

essential factor in higher education admissions.

30See Calvin Bradford, Center for Community Change, Risk or

Race? Racial Disparities and the Subprime Refinance Market (2002);

see id. at vii (“Lower-income African-Americans receive 2.4 times as many

subprime loans as lower-income whites, while upper-income African-

Americans receive 3.0 times as many subprime loans as do whites with

comparable incomes.”).

14

The legacy of racial subjugation is acutely evident in the

persistence of residential segregation. Where one lives affects

one’s schooling, peer groups, safety, job options, insurance

costs, political clout, access to public services, home equity,

and, ultimately, wealth.31 While America has become

increasingly racially diverse, blacks in major metropolitan areas

continue to be extremely racially isolated in a manner unlike

any other ethnic group in this country.32 This is true for all

black Americans, regardless of income level.33 Even middle

class black Americans tend to live in areas with a higher

concentration of poverty, higher crime rates, and less access to

services than white neighborhoods.34 Blacks are also less likely

31Douglas S. Massey & Nancy A. Denton, American Apartheid

235 (1993).

32See, e.g., JOHN ICELAND, ETAL., U.S. CENSUS BUREAU, RACIAL AND

Ethnic Segregation in the United States: 1980-2000 3-4 (2002);

Massey & Denton, supra n. 31, at 77.

33See, e.g., Massey & Denton, supra n. 31, at 84-87 (noting that blacks

in Detroit are extremely racially isolated regardless of income); Douglas S.

Massey & Mary J. Fischer, Does Rising Income Bring Integration? New

Results for Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians in 1990, 28 SOC. SCI. Res. 316,

317 (1999) (finding that blacks “continue to lag well behind other groups in

achieving integration, irrespective of social class.”); Mary Pattillo-

McCoy, Black Picket Fences 27 (1999) (“African Americans have long

attempted to translate socioeconomic success into residential mobility,

making them similar to other ethnic groups. They desire to purchase better

homes, [to live in] safer neighborhoods, [and to attend] higher quality

schools . . . with their increased earnings. . . . The black middle class has

always attempted to leave poor neighborhoods, but has never been able to

get very far.”) (citation omitted).

34Camille Zubrinsky Charles, Socioeconomic Status and Segregation:

African Americans, Hispanics and Asians in Los Angeles, in PROBLEM OF

THE Century 284-85 (Elijah Anderson & Douglas S. Massey eds., 2001).

See also Gary Orfield, Harvard U., Schools More Separate 11,17

(2001) (“Even most of the middle class minority families who move their

children to the suburbs find themselves in heavily minority schools, often

15

to own homes than whites. While home ownership increased

to an overall rate of 66.8% in 1999, a disparity of 26%

remained between black and white ownership rates.35

In Michigan, the vast majority of whites and blacks live in

separate worlds. In 2000, Detroit ranked as the most racially

segregated city of the 50 largest metropolitan areas in this

nation.36 Within the last decade, four other Michigan

metropolitan areas have ranked in the nation’s top twenty-five

most racially segregated urban areas.37 This extreme racial

isolation is a direct result of a history of state-backed

discriminatory policies and practices,38 and continuing private

schools with limited educational success.”); Richard D. Alba et al., How

Segregated are Middle-Class African Americans? 47 Soc.Probs. 543,556

(2000) (“At no point do blacks attain residential parity with whites—that is,

the communities in which they reside have less affluence and other less

desirable characteristics (e.g., more crime) than the communities where

whites with similar personal and household characteristics are found.”); John

R. Logan & Brian J. Stults, Racial Differences in Exposure to Crime: The

City and Suburbs o f Cleveland in 1990, 37 CRIMINOLOGY 251, 270 (1999)

(concluding that residential segregation restricts affluent African Americans

to neighborhoods with “more than double the violent crime rate to which

poor whites are exposed.”).

35Geqrge S. M asnick, Harvard U., Home Ownership Trends and

Racial Inequality in the United States in the Twentieth Century,

22, 24 (2001) available at http://www.ichs.harvard.edu/publications/

homeown/masnick_wO 1 -4.pdf.

36Leland Ware & Antoine Allen, The Geography o f Discrimination:

Hypersegregation, Isolation and Fragmentation Within the African-

American Community, in THE STATE OF BLACK AMERICA 2002 69,74 (Lee

A. Daniels ed., 2002).

37Sugrue, supra n. 22, at 22.

38As Detroit’s white population suburbanized, opposition to racial

diversity reached into suburban communities. In Dearborn, city officials

collaborated with real estate firms to fight against mixed-income housing

which, they asserted, would become a “dumping ground” for blacks and

other minorities. Today, Dearborn is predominantly white, while Detroit,

http://www.ichs.harvard

16

discrimination.39

Such persistent racial segregation has had profound

consequences for black Americans, particularly in the area of

education. Fifty years ago, Brown signaled the promise of a

more racially inclusive society; today, however, we are more

than a decade into the continuous resegregation of American

public schools. The racial isolation of black students has

increased to levels not seen in three decades. The nation’s

largest city school systems are, almost without exception,

overwhelmingly nonwhite. White students are the most

segregated; on average, they attend schools where eighty

percent of the student body is white.40

This racial balkanization of American schools is a direct

result of the deeply rooted racial caste system that continues to

permeate our society and to wreak havoc on the life

opportunities of black children. This Court correctly ruled 50

years ago in Brown that “separate is inherently unequal.” Yet,

one-sixth of all black students in the nation and one-fourth of

black students in the Northeast and Midwest are educated in

virtually all-non-white schools that have concentrations of

enormous poverty and very limited resources.41 Segregated

schools have lower average test scores, fewer qualified

teachers, and fewer advanced courses.42 Many black students,

regardless of their family income, have markedly diminished

its neighbor, is predominantly black. See Sugrue, supra n. 22, at 29.

39Ware & Allen, supra n. 36, at 76 (at least one in four blacks seeking

housing today can expect to encounter some form of housing

discrimination).

40Frankenberg et al., supra n. 20, at 4-5.

41 Id. at 5.

42Id. at 11.

17

opportunities for educational, social, and economic

advancement.43 The same cannot be said for the majority of

poor white Americans.44

The persistence of residential segregation and these

disparate educational opportunities are compounded by the

continued exclusion of African Americans from full

participation in the political process. Even today, racially

polarized voting remains as pervasive in many parts of the

country45 as it was almost forty years ago when Congress

enacted the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C. § 1973

(2002), for the purpose of dismantling the many invidious

practices that denied the franchise to black voters.46

The specter of apartheid also haunts African Americans’

opportunity for occupational advancement. The risk of

unemployment looms larger for African Americans than for

Vvhites, both in good economic times and in bad.47 Despite the

43These inequalities also extend to the treatment of black and white

youth in the criminal justice system. Young blacks who are arrested and

charged with a crime are more than six times more likely to be sentenced to

prison than similarly situated whites. Manning Marable, The Great

Walls of Democracy 158 (2002).

^Gary Orfield, The Growth o f Segregation, in DISMANTLING

Desegregation, supra n. 24, at 53 (most segregated African-American

and Latino schools are dominated by poor children, but 96 percent of white

schools have middle-class majorities).

4SEven after the most recent round of redistricting, there continue to be

judicial findings of “highly racially polarized voting.” See, e.g.,Georgia v.

Ashcroft, 195 F. Supp. 2d 25, 88 (D.D.C. 2002), prob. juris, noted, 71

U.S.L.W. 3486, 2003 D.A.R. 698 (U.S. 2003).

46See, e.g., South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301, 308-09, 315

(1966) (describing the purpose of the Voting Rights Act); Beer v. United

States, 425 U.S. 130, 140 (1976) (quoting H.R. Rep. No. 196, 94th Cong.,

1st Sess. 57-58 (1975)) (same).

47 For example, while the white male unemployment increased from 4.6

18

enactment of federal and state anti-discrimination laws,

employment discrimination against African Americans still

exists across all regions, in all industries and in all occupations,

affecting as many as 2 million minority and female workers.48

For the 2002 year, both the mean and median weekly earnings

of whites exceeded those of blacks in virtually every

occupational group.49 All factors being equal, blacks on

average are less likely to receive job offers than whites.50 This

discrimination exacerbates the barriers already created by

segregated social networks and informational bias that infects

employment opportunity for blacks.51 Access to the highest

to 4.9 percent during the period from January, 2002 to January, 2003, black

male unemployment jumped from 8.8 to 10.3 percent over the same time

period. As of January, 2003, black teenage unemployment stood at 30.4%

compared to 15.2 for comparably aged whites. U.S. Bureau of Labor

Statistics, Table A-2, Employment Status ofthe Civilian Population

BY R a c e , S e x a n d AGE, ( 2 0 0 3 ) a v a i l a b l e a t

http://www.bls.gov/news.release/ empsit.t02.htm.

48Alfred W. Blumrosen & Ruth G. Blumrosen, The Reality of

Intentional Job Discrimination in Metropolitan America— 1999,230

(1999) available at http://www. eeol.com/1999_NR/ Chapterl7.pdf.

450 ffice of Employment and Unemployment Statistics, U.S.

Bureau of Labor Statistics, table a-19, Usual Weekly Earnings of

Employed Full-Time Wage and Salary Workers by Occupation, Sex,

Race and Hispanic Origin, 2002 Annual Averages, at 13-16, 25-28.

(Unpublished and available by contacting Bureau of Labor Statistics).

50Harry J. Holzer, Race Differences in Labor Market Outcomes Among

Men, in 2 AMERICA BECOMING 106 (Neil J. Smelser et al. eds., 2001);

Ronald B. Mincy, The Urban Institute Audit Studies, in CLEAR AND

Convincing Evidence 173-74 (Michael Fix & Raymond J. Struyk, eds.

1993).

5IJomills Henry Braddock II & James M. McPartland, How Minorities

Continue to be Excluded from Equal Employment Opportunities A3 J. OF

SOC. Issues 27 (1987); see also Harry J. Holzer & Keith R. Ihlanfeldt,

Customer Discrimination and Employment Outcomes for Minority Workers,

113Q.J.OFECON. 835-67 (1998).

http://www.bls.gov/news.release/_empsit.t02.htm

http://www

19

paying occupations is also much more restricted for African

Americans than whites both in terms of the range of positions

available, compensation, and the educational and experience

requirements for selection.52 Such racial discrimination persists

across all class levels and affects even those African Americans

with advanced skills and credentials.53

Despite modest economic progress, the black middle class

still lags overwhelmingly behind their white counterparts in

income and occupational status. The salience of race, over

class, in determining socioeconomic mobility became more

pronounced in the 1980s when “60 percent of whites but only

36 percent of African Americans from upper-white-collar

backgrounds were able to maintain their parents’ occupational

status.” Lower middle class whites also proved more upwardly

mobile, with more than half finding their way into upper middle

class jobs, “compared to only 30 percent of blacks.” African

Americans were also more downwardly mobile.54

52Marlese Durr & John R. Logan, Racial Submarkets in Government

Employment, 12 Soc. F. 353-70 (1997); Sharon M. Collins, The

Marginalization o f Black Executives, 36 SOC. PROBS. 317-31 (1989);

Sharon M. Collins, Blacks on the Bubble, 34 Soc. Q. 429-47 (1993);

Melvin E. Thomas, Race, Class and Personal Income, 40 SOC. PROBS. 328,

339-40 (1993); Melvin E. Thomas et al., Discrimination Over the Life

Course, 41 SOC. PROBS. 608-28 (1994); George Wilson et al., Reaching the

Top: Racial Differences in Mobility Paths to Upper-Tier Occupations, 26

W ork & Occupations 165,166,175 (1999).

53Marianne Bertrand & Sendhil Mullainathan, Are Emily and

Brendan More Employable than Lakisha and Jamal? A Field

Experiment on Labor Market Discrimination, 1, 14-15 (2002)

available at http://gsb.uchicago.edu/pdf/bertrand.pdf.

siSee, e.g., MARY Patitllo-McCOY, supra n. 33, at 21; see id. (“In

income, the gap between what whites earn and what African Americans earn

has not shown signs of narrowing since the early 1970s. For younger

workers, the gap may in fact be increasing. The reversal of the trend toward

earnings equality is especially pronounced among college-educated African

Americans, partly because of their concentration in declining sectors of the

http://gsb.uchicago.edu/pdf/bertrand.pdf

2 0

By 1995, the percentage of black workers in middle class

occupations had grown to half, “while 60 percent of whites had

middle class jobs.” Yet even these figures mask the significant

differences in occupational distribution between the black and

white middle class, with blacks tending to occupy lower paying

jobs with less prestige.55

Not surprisingly, this lack of black occupational opportunity

has resulted in continued racial disparities in access to capital

and in the accumulation of wealth. As of 2000, 22.1% of

African Americans lived below the federal government’s

poverty line, compared to 7.5% of white non-Hispanics.56

Between 1984 and 1999, the mean household wealth for white

families increased from $51,600 to $103,600; for black

families, it rose from a meager $6,100 to $9,100.57

African Americans also suffer from less adequate health

services and treatment relative to whites. This is true across a

variety of medical conditions, and occurs independently of

insurance status, income, and education, among other factors

that influence access to healthcare. These disparities are

markedly present in the care that African Americans receive for

cardiovascular conditions, various cancers, strokes, kidney

disease, HIV/AID8, diabetes, and mental health. Moreover,

these disparities are associated with greater mortality among

African-American patients.58 African Americans experience

economy . . . . ”).

55Mary Pattillo-McCoy, supra n. 33, at 21-22.

56Joseph Dalaker, U.S. Census Bureau, Poverty in the United

States, 2000 4 (2001).

57Joseph Lupton & Frank Stafford, Household Financial Wealth,

(Thousands o f 1999 Dollars), Institute for Social Research (Jan. 2000),

available at http://www.isr.umich.edu/src/psid/wealthcomp.pdf.

58Brian D. Smedley et al., Institute of Medicine of the Nat’l

http://www.isr.umich.edu/src/psid/wealthcomp.pdf

21

infant morality rates two to three times that of whites and have

a lower life expectancy.59

Despite significant progress by some African Americans, the

chasm between blacks and whites remains enormous.60 In the

absence of slavery, de jure segregation and persistent “societal

discrimination,” this generation of applicants might have lived

in a society where 700,000 more African Americans have jobs,

and nearly two million more African Americans hold higher

paying and managerial jobs. They might have lived in a society

where the average African-American household earns 56%

more than at present, and altogether, African-American

households earn another $190 billion.

Similarly, the wealth of black households would have risen

by $ 1 trillion. African Americans might have had $200 million

more in the stock market, $120 billion more in our pension

plans, and $80 billion more in the bank. African Americans

could have owned over 600,000 more businesses, with $2.7

trillion more in revenues. There might have been 62 African

Americans running Fortune 500 companies, rather than three.

Two million more African Americans could have high school

diplomas, and nearly two million more could have

undergraduate degrees. Close to ahalf-million more could have

master’s degrees. If racial disparities did not exist in health

Academies, Unequal Treatment, 42-79, 59 (blacks less likely to be

found eligible for transplants, to appear on transplant waiting lists, and to

undergo transplant procedures, even after controlling for patients’ insurance

and other factors) (2003).

59 N ational Center for Health Statistics, Department of Health

and Human Services, Table 23, Infant Mortality Rates, Fetal Mortality

Rates, and Perinatal Mortality Rates, According to Race (2001), available

at http://www.cdc.gov/ nchs/data /hus/tables/2001/01hus023.pdf.

mSee Janice F. Madden, Do Racial Composition and Segregation Affect

Economic Outcomes in Metropolitan Areas?, in PROBLEM OFTHECENTURY,

supra n. 34, at 314.

http://www.cdc.gov/_nchs/data_/hus/tables/

2 2

insurance rates, 2.5 million more African Americans, including

620,000 children, could have health insurance. Three million

more African Americans might have owned homes.61

The inescapable conclusion is that this is not a “color blind”

society where opportunity is singularly determined according to

individual ability. Rather, it is a socially-constructed racial

hierarchy with whites firmly on top. The only other

conceivable explanation — that this gross inequality is the

consequence of a natural order of black inferiority and white

supremacy — is, of course, wholly unacceptable.62

III. The Fourteenth Amendment Should Not Be

Interpreted to Frustrate Voluntary State Efforts,

Using Race-Conscious Remedies, to Eliminate the

C o n t in u in g E f fe c t s o f S t a t e -S p o n so r e d

Discrimination.

As detailed above, this country faces a crisis of racial

inequality, which has had the ripple effect of removing untold

numbers of African Americans from the pool of individuals

s1Franklin D. Raines, What Equality Would Look Like, in The State

of Black America, supra n. 36, at 17-20. Of course, no one would expect

exact parity even in the absence of discrimination. But, the magnitude of the

difference between actual conditions and any rough estimates of parity

suggests the kind of “manifest imbalance” that this Court has found

appropriate for race conscious remedies. Johnson v. Transp. Agency, 480

U.S. 616 (1987); see also, Hazelwood Sch. Dist. v. United States, 433 U.S.

299, 308 n. 14 (1977).

62 This was the view Justice Harlan in fact endorsed in his famous Plessy

dissent:

The white race deems itself to be the dominant race in this country. And

so it is, in prestige, in achievements, in education, in wealth, and in

power. So, I doubt not it will continue to be for all time, if it remains

true to its great heritage and holds fast to the principles of constitutional

liberty.

Plessy, 163 U.S. at 559.

23

eligible to compete for admission to selective institutions of

higher education, including the University of Michigan. See,

e.g., Bakke, 438 U.S. at 370-71 (Opinion of Brennan, White,

Marshall & Blackmun, JJ.). It has also provided unfair

advantages to whites as a group, who have disproportionately

benefitted from the racialized dimensions of economic,

political, and social opportunity in our country .63 This systemic

and systematic racial inequality, from cradle to grave, makes

consideration of race not only relevant, but essential, to public

institutions in today’s society.

Yet the Court’s jurisprudence, especially its ruling in Bakke,

has dismissed this rooted inequality as “societal discrimination”

that is beyond the power of state actors to remedy. See City o f

Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co., 488 U.S. 469 (1989); Bakke, 438

U.S. at 307. This makes it virtually impossible for a public

institution voluntarily to take account of race, short of

implicating itself in identified racial discrimination, which such

institutions, concerned about their own liability, are frequently

unwilling to do. Cfi Wygant v. Jackson Bd. ofEduc., 476 U.S.

274, 291 (1986) (O’Connor, J., concurring) (public employers

might be “trapped between the competing hazards of liability to

minorities if affirmative action is not taken . . . and liability to

non-minorities if affirmative action is taken”). The inability of

state and local institutions to act voluntarily to relieve this

continuing disparity threatens to relegate African Americans to

a permanent third class status, without legally cognizable means

for redressing systemic racial disadvantage brought on by such

institutions throughout hundreds of years of slavery,

segregation, and discrimination. It further threatens to create a

permanent drain on this country’s pool of potential talent and,

ultimately, to produce a society forever divided by race. As

63 See generally, Cheryl I. Harris, Whiteness as Property, 106 Harv. L.

Rev . 1707 (1993); Barbara J. Flagg, “Was Blind, But Now I See, ” 91 MICH.

L. Re v . 953 (1993).

24

Justice Marshall concluded in Bakke:

In light of the sorry history of discrimination and its

devastating impact on the lives of Negroes, bringing the

Negro into the mainstream of American life should be a

state interest of the highest order. To fail to do so is to

ensure that America will forever remain a divided society.

438 U.S. at 396 (Opinion of Marshall, J.). The Court’s

unwillingness to endorse race-conscious remedies aimed at

mitigating the pernicious effects of widespread discrimination

is contrary to the purpose and spirit of the Fourteenth

Amendment. See id. (“I do not believe that the Fourteenth

Amendment requires us to accept that fate. Neither its history

nor our past cases lend any support to the conclusion that a

university may not remedy the cumulative effects of society’s

discrimination---- ”); id. at 407 (Opinion of Blackmun, J.) (“In

order to get beyond racism, we must first take account of race.

There is no other way. And in order to treat some persons

equally, we must treat them differently. We cannot — we dare

not — let the Equal Protection Clause perpetrate racial

supremacy.”).

A. The Persistence of Pervasive Racial Inequality Calls For

the Court to Revisit its Conclusion In Bakke That

Redressing “Societal Discrimination” Is Not A

Compelling Interest

In an opinion authored by Justice Powell, a majority of the

Court in Bakke rejected the University of California at Davis

Medical School’s use of race to redress the effects of “societal

discrimination,” which it deemed “an amorphous concept of

injury that may be ageless in its reach into the past.”64 438 U.S.

“The Court’s rejection of the goal of eliminating “societal

discrimination,” however, was far from unanimous. Four Justices expressly

repudiated this view. Justices Brennan, White, Marshall, and Blackmun

dissented from that part of the Court’s judgment holding the UC Davis plan

25

at 307. In the “absence of judicial, legislative, or administrative

findings of constitutional or statutory violations,” id., the Court

concluded that it could not sanction a classification aimed at

assisting “persons perceived as members of relatively

victimized groups at the expense of other innocent individuals,”

id.

None of the opinions that emerged from Bakke defined

“societal discrimination.” Nor has the Court defined it since.

Cf. Croson, 488 U.S. 469; Wygant, 476 U.S. 274. But it has

placed beyond the scope of constitutionally permissible

remedies a range of actions taken by state actors to redress the

cumulative effects of past discrimination. Thus, for example,

in Wygant the Court disapproved a school board’s race-based

layoff policy that aimed to create a more diverse faculty, in

order to have role models for minority students, in the absence

of “some showing of prior discrimination by the governmental

unit involved.” 476 U.S. at 274. Similarly, the Court in Croson

rejected an ordinance adopted by the Richmond City Council

that required set-asides to minority-owned businesses in part

because findings by the City Council concerning the deep

disparity between the share of contracts awarded minority-

owned businesses and the size of Richmond’s minority

population were held insufficient. 488 U.S. at 501. The local

government could act, the Court determined, only to “eradicate

the effects of private discrimination within its own legislative

jurisdiction.” Id. at 491-92.* 65

At the same time, efforts to hold state and local institutions

accountable for the consequences of their past discrimination

unconstitutional, concluding that the University could consider race to

counter the lingering effects of “societal discrimination.” Bakke, 438 U.S.

at 362-73.

65The Court concluded that a state actor could also act to redress its

“passive participation” in a “system of racial exclusion practiced by

elements of the local construction industry .. . . ” Id. at 492.

2 6

have been hobbled by courts’ determinations that the effects of

such discrimination are too “attenuated” or “amorphous” to

justify race-conscious remedies, and that racially segregated

systems are the product of private choices, rather than state

action, and, therefore, are not legally redressable. See, e.g.,

Freeman, 503 U.S. at 494-95; cf. Jenkins, 515 U.S. 70;

(limiting federal courts’ remedial authority in school

desegregation cases); Dowell, 498 U.S. at 250-51 (Opinion of

Marshall, Blackmun, and Stevens, JJ). (school board released

from desegregation decree following period of compliance

could adopt student assignment plan that resulted in

reappearance of all-black schools in absence of a showing that

decision to implement plan was intentionally discriminatory);

Pasadena City Bd. ofEduc. v. Spangler, 427 U.S. 424 (1976);

Milliken, 418 U.S. 717; Belk v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. o f

Educ., 269 F.3d 305 (4* Cir. 2001); Manning v. Sch. Bd. o f

Hillsborough County, 244 F.3d 927 (11th Cir. 2001). These

decisions have the effect of sanctioning a range of outcomes

that originated with state and local actors and continue to

perpetuate racial disadvantage. See, e.g., Dowell, 498 U.S. at

251 (dissenting opinion)(school board maintained original dual

system by “exploiting residential segregation”).

The combined impact of the Court’s Fourteenth Amendment

jurisprudence has been to squeeze both ends against the middle

— shielding from constitutional scrutiny policies which, though

neutral on their face, have a disproportionate adverse impact on

African Americans, see, e.g., Village o f Arlington Heights v.

Metropolitan Hous. Auth., 429 U.S. 252 (1977); Washington v.

Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976); cf. Personnel Admin’ r ofMass. v.

Feeney, 442 U.S. 256 (1979) (Equal Protection violation exists

only if state policy was adopted because of, rather than merely

in spite of, its disparate impact on suspect class); Rodriguez,

411 U.S. 1 (state method of financing education through

property taxes held not to violate Equal Protection Clause

despite significant adverse impact on poor children), while at

27

the same time barring affirmative measures taken to alleviate

the impact of systemic racial inequality, see Croson, 488 U.S.

469; Wygant, 476 U.S. 274; Bakke, 438 U.S. 265.66

It is ironic, moreover, that the Fourteenth Amendment has

been interpreted to hamstring voluntary state efforts to

compensate for past discrimination, considering that state actors

have been the most determined to frustrate the mandate of

Brown. Well after the Court’s decision in Brown, Southern

states continued their vocal opposition to measures to ensure