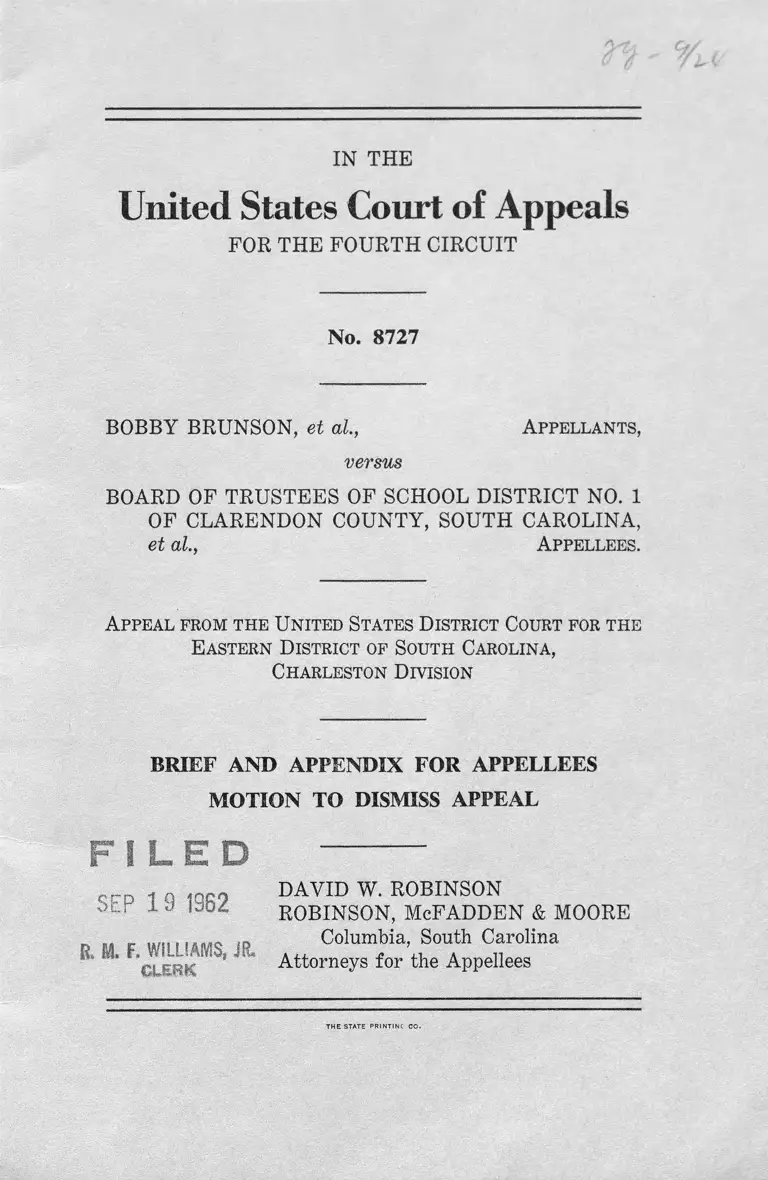

Brunson v Board of Trustees of School District No 1 of Clarendon County South Carolina Brief and Appendix for Appellees

Public Court Documents

September 19, 1962

21 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Brunson v Board of Trustees of School District No 1 of Clarendon County South Carolina Brief and Appendix for Appellees, 1962. 2e4d20f4-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/dd6d4ec0-ce6f-4e15-ad67-da37f4a4acac/brunson-v-board-of-trustees-of-school-district-no-1-of-clarendon-county-south-carolina-brief-and-appendix-for-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 8727

BOBBY BRUNSON, et al., A ppellants,

versus

BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 1

OF CLARENDON COUNTY, SOUTH CAROLINA,

et al, A ppellees.

A ppeal from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of South Carolina,

Charleston Division

BRIEF AND APPENDIX FOR APPELLEES

MOTION TO DISMISS APPEAL

F I L E D

SEP 13 1362

R, Rg. F. WILL!AMS, JR.

CLERK

DAVID W. ROBINSON

ROBINSON, McFADDEN & MOORE

Columbia, South Carolina

Attorneys for the Appellees

TH E STATE 1C CO.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Statement of the Case_______________________________ 1

I. The Order of the District Court is Not Appealable 1

II. The Suit is Not a Proper Class A ction___________ 5

Conclusion _________________________________________ 12

Appendix __________________________________________ 21a

Motion to Dismiss Appeal__________________________ lb

Cases Page

All-American Airways v. Eldred, 209 F 2d 247

(2nd Cir.) _____________________________________ 2, 3

American Broadcasting Co. v. Wahl, 121 F. 2d 412

(2nd Cir.) _____________________________________ 4

Atwater v. North American Coal Co., I l l F. 2d 125

(2nd Cir.) _____________________________________ 4

Baltimore Contractors v. Bodinger, 348 U. S. 176___ 5

Bedser v. Horton, 122 F. 2d 406 (4th Cir. 1941) ___ 9

Briggs v. Elliott, 98 F. Supp. 529 (1951), 342 U. S.

350 (1952) ; 103 F. Supp. 920 (1952) ; 347 U. S.

483 (1954; 349 U. S. 294 (1955) ; 132 Supp 776

(1955) ----------------------------------------------------- 6 ,7 ,8 ,9 ,1 0

Brown v. Board, 347 U. S. 483 (1954) ; 349 U. S. 294

(1955) _________________________________________ 7-9

Carson v. Board, 227 F. 2d 789 ____________________ 8

Carson v. Warlick, 238 F. 2d 724, c.d. _____________ 8

Clark v. Kansas City, 172 U. S. 334 (1899) _________ 4

Collins v. Metro-Goldwyn, 106 F. 2d 8 3 _____________ 9

Collins v. Miller, 252 U. S. 364 __ ______ __________ 5

Covington v. Edwards, 264 F. 2d 780 _______________ 8

Davis v. Prince Edward, 142 F. Supp. 616 _________ 8

Davis v. Yellow Cab Co., 220 F. 2d 790 (5th Cir.

1955) ___________________________________________ 9

Gillette v. Northern Oklahoma, 179 F. 2d 711 (10th

Cir. 1950) ______________________________________ 9

Henderson v. U. S., 339 U. S. 8 1 6 _________________ 7

Hohorst v. Hamburg, 148 U. S. 261__________ _____ 4

Holt v. Raleigh, 265 F. 2d 98, c .d .__________________ 8

Hood v. Board. 232 F. 2d 626, 286 F. 2d 236 ______ _ 8, 9

International Machinists v. Street, 367 U. S. 740 ___ 7

Joham v. Roger, 296 F. 2d 119 12nd Cir.) _______ 4

Jumps v. Leverone, 150 F. 2d 876 (7th Cir.) _______ 2

Kansas City v. Williams, 205 F. 2d 47 (8th Cir.) c.d. 9

TABLE OF CITATIONS

ii

TABLE OF CITATIONS— Continued

Cases Page

Kennedy v. Bethlehem Steel Co., 102 F. 2d 141

(3rd Cir.) _____________________________________ 5

Markham v. Kasper, 152 F. 2d 270 (7th Cir.) ______ 4

Martinez v. Maverick, 219 F. 2d 666 (5th C ir.)__ 9

Metropolitan v. Banion, 86 F. 2d 886 ( 10th Cir.) __ 4

McCabe v. Atcheson, 235 U. S. 151_________________ 7

McLaurin v. Oklahoma, 339 U. S. 637 _______________ 7

Missouri, ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337 ___ 7

Mitchell v. U. S., 313 U. S. 8 0 ______________________ 7

Oppenheimer v. Young, 144 F. 2d 387, 3 F.R.D.

(2nd Cir.) _____________________________________ 2

Reddix v. Lucky, 252 F. 2d 930 (5th Cir. 1958) ____ 8

Rogers v. Alaska Steamship Lines, 249 F. 2d 646

(9th Cir.) ______________________________________ 2

Shultz v. Manufacturers & Traders, 103 F. 2d 771

(2nd Cir.) _____________________________________ 4

Shuttleworth v. Birmingham, 358 U. S. 101 (1958)__ 8

Skirvin v. Mesta, 141 F. 2d 668 (10th Cir.) _________ 4

U. S. v. Shaughnessy, 178 F. 2d 756 (2nd Cir.) ____ 4

U. S. Plywood Corp. v. Hudson, 210 F. 2d 462

(2nd Cir.) _____________________________________ 5

Whiteman v. Pitrie, 220 F. 2d 914 (5th Cir. 1955) __ 9

Statutes

Fair Labor Standards A c t _________________________ 3

South Carolina Code 1952

Section 21-230 ________________________________ 21a

Section 21-230(9) _____________________________8-21a

Section 21-230.2 _____________________________ 21a

Section 21-247 ________________________________ 8-21a

Section 21-247.2 _____________________________ 22a

Section 21-247.3 _____________________________ 22a

Section 21-247.4 _____________________________ 22a

Section 21-247.5 _____________________________ 22a

28 U.S C A. 1291__________________________________ 2-5

28 U.S.C.A. 1292__________________________________ 2

iii

IN THE

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 8727

BOBBY BRUNSON, et al, A ppellants,

versus

BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 1

OF CLARENDON COUNTY, SOUTH CAROLINA,

et al., A ppellees.

A ppeal from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of South Carolina,

Charleston Division

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The plaintiffs appeal from the order of the District Court

in which it determined that “ this action is not properly-

brought as a class action under Rule 23 (a) 3.” It there

fore struck from the complaint the names of all of the

plaintiffs except the one first named and all allegations

in the complaint inappropriate to a personal cause of action

in behalf of that plaintiff. The plaintiff was given leave

to file an amended complaint. (18a-19a) I

I

The Order of the District Court is Not Appealable

It is our position that the order of the District Court is

not a final decision from which an appeal is authorized

2 Bobby Brunson, et al. v. Board of T rustees, et al.

under Title 28 Section 1291.1 Since the appellate jurisdic

tion of this Court is statutory, the appeal does not lie un

less this Court concludes that the District order is a final

judgment. Orders striking the class character of pleadings

are not final decisions within the meaning of Section 1291.

Oppenheimer v. Young, 144 F. 2d 387, 3 F.R.D. (2nd Cir.) ;

Jumps v. Leverone, 150 F. 2d 876, 877 (7th Cir.) ; All-

American Airways v. Eldred, 209 F. 2d 247 (2nd Cir.) ;

Rogers v. Alaska Steamship Lines, 249 F. 2d 646 (9th

Cir.).

In Oppenheimer the Court stated the facts of that case

and the applicable law in these words:

This suit was brought as a spurious class action

and is sought to be sustained under Federal Rule

23(a) (3) 28 U.S.C.A. following section 723c. The

plaintiffs, after two unsuccessful attempts to set forth

their claim in the form of a spurious class action, filed

a second amended complaint which was dismissed by

the District Court on the ground that the plaintiffs

and the parties whom they sought to represent had

divergent interests, with leave, however, to serve a

further amended complaint in their own behalf; but,

because of failure to amend, as permitted, a judgment

was entered dismissing the second amended complaint

in its entirety. The plaintiffs have appealed from

both the order and the judgment. Inasmuch, however,

as the order provided for an amendment, it did not

dispose of the litigation and it was not final. The in

dividual claims of the tivo plaintiffs asserted in the

second amended complaint, and sustained by the inter

locutory order, arose out of the same matters as those

upon which the class action was founded, and there

must be finality in the disposition of both in order that

an appeal may lie.1 2 Audi Vision, Inc. v. RCA Mfg.

1 While appeals from some interlocutory orders are permitted, the order

here in issue does not come within the purview of 28 U. S. C. A. 1292.

2 Emphasis supplied in this brief.

Bobby Brunson, et al. v. Board of T rustees, et al. 3

Co., 2 Cir., 136 F. 2d 621, 147, A.L.R. 574; Western

Elec. Co. v. Pacent Reproducer Corp., 2 Cir., 37 F. 2d

14. The appeal from the interlocutory order must,

therefore, be dismissed.

In the Jumps case the five plaintiffs sued for themselves

and as representatives of a great number of other

employees to recover wages and overtime under the provi

sions of the Fair Labor Standards Act. The Seventh Cir

cuit in dismissing an appeal questioning the District

Court’s order striking from the complaint “ all reference

to other establishments and to employees therein,” said:

Whether the proceeding be looked upon as a statu

tory proceeding to liberalize the joinder of parties un

der Section 16 of the Fair Labor Standards Act, or

as a spurious class suit pursuant to the Federal Rules

of Civil Procedure, Rule 23(a) (3), the District Court

had a wide discretion in shaping up the limits of the

suit.

Congress intended to liberalize and relax the pro

cedure for bringing suits to enforce the sanctions of

the Act. The procedure was left to the Court’s discre

tion in order that they might control the limits of such

suits in the interest of justice to the parties under the

Act. When one contemplates the scope of the suit en

visaged by the attorneys for the plaintiffs, and the

ramifications of a suit of that size, purporting to affect

the rights of thousands of persons in ten or more

states, we think that where the Court attempted to

reasonably limit the scope of the suit it was exercising

its discretion and the order made and sought to be

appealed from is interlocutory and not final, and

therefore is not appealable. The motion of the defend

ants to dismiss this appeal is sustained and the appeal

is dismissed.

In the All-American Airways case ten airlines sued the

officials of the town of Cedarhurst to have its ordinance

4 Bobby Brunson, et al. v . Board of T rustees, et al.

prohibiting low flying of planes taking off and landing at

Idlewild declared invalid and for appropriate injunctive

relief. These town officials in behalf of themselves indi

vidually as property owners and in behalf of other property

owners counterclaimed to enjoin low flying by the plain

tiffs.

The District Court granted the plaintiffs’ motion “ to dis

miss the counterclaims as to the so-called ‘related defend

ants’ and order the answer amended accordingly, i.e., by

the elimination of all allegations of a class suit.” From a

reading of the opinion it is obvious that the Court of Ap

peals disagreed with the merits of the District order. How

ever the Court held: “ In any event the non-appealability of

the order in this type of class action is apparent.”

These decisions as to the non-appealability of orders re

lating to class actions are consistent with the holding of the

various circuits that orders granting motions to dismiss

with leave to plead anew are not appealable. (Atwater v.

North American Coal Co., I l l F. 2d 125 (2nd Cir.) ; Amer

ican Broadcasting Co. v. Wahl, 121 F. 2d 412 (2nd Cir.) ;

U. S. v. Shaughnessy, 178 F. 2d 756, 757 (2nd Cir.) ; Clark

v. Kansas City, 172 U.S. 334 (1899).) An order dismissing

a complaint unless the plaintiff produced its managing of

ficer for examination within ninety davs is not an appeal-

able final judgment even at the end of the ninety-day pe

riod. (Joham v. Roger, 296 F. 2d 119 (2nd Cir.).)

Orders granting or denying consolidation under Rule

42 (a) where there is a common question of law or fact are

not appealable. Skirvin v. Mesta, 141 F. 2d 668, 671 (10th

Cir.). Orders striking allegations of a complaint are not

appealable since they are not final judgments. (Metro

politan v. Banion, 86 F. 2d 886 (10th Cir.) ; Shultz v. Man

ufacturers & Traders, 103 F. 2d 771 (2nd Cir.) ; Markham

v. Kasper, 152 F. 2d 270 (7th Cir.).) Unappealable are

orders determining the issues as to some but not all of the

parties. (Atwater v. North American Coal, 111 F. 2d

125 (2nd Cir.) ; Hohorst v. Hamburg, 148 U. S. 261.) An

Bobby Brunson, et al. v. Board of T rustees, et al. 5

order granting summary judgment for the plaintiff on the

defendant’s counterclaim is not appealable. ( U. S. Ply

wood Corp. v. Hudson, 210 F. 2d 462 (2nd C ir.).) An order

dismissing a petition to intervene is not appealable. [Ken

nedy v. Bethelhem Steel Co., 102 F. 2d 141, 142 (3rd C ir.).)

There Circuit Judge Maris pointed out that, “ Not only is

it a discretionary order but it leaves the petitioner at full

liberty to assert his rights in any other appropriate form

of proceeding.”

Section 22 of the Judiciary Act of 1789, 1 Stat., 73,

84 provided that appeals in civil actions should be

taken to the circuit courts only from final decrees and

judgments. That requirement of finality has remained

a part of our law ever since, and now appears as Sec

tion 1291 of the Judicial Code.

Baltimore Contractors v. Bodinger, 348 U. S. 176, 178. Cf.

7ollins v. Miller, 252 U. S. 364, 370.

When we consider the district order in the light of these

Gcisions it is clear that it lacks the finality contemplated

b Section 1291. The cause has not been terminated. The

piintiff Bobby Brunson is still in court with the right to

fil an amended complaint. The order does two things: (1)

It'trikes from the body of the complaint certain allega-

tios. Such an order is clearly not appealable. (2) It

str-es from the caption and the body of the complaint eer-

taimamed plaintiffs. Since these plaintiffs are free to

purie an appropriate remedy in another action and since

Bobr Brunson’s cause is still before the court, the order

is indocutory. Therefore the appeal should be dismissed.

II

The Suit Is Not a Proper Class Action

Theefendant School District No. 1 (Summerton) of

Clarentn County is a rural school district in lower South

Carolinlying along the Santee-Cooper reservoir and the

6 Bobby Brunson, et al. v. Board of T rustees, et al.

lower Santee River. The latest available figures of school

enrollment (1961-1962) showed 326 white pupils, 2,572

Negro.

It is the same school district before the Court in Briggs v.

Elliott.3 Brunson v. Board is a companion case to Briggs.

The defendants in both are the school authorities in the

Summerton District. The complaint in Brunson alleges

that some but not all of the plaintiffs are the same. (8a ).

Both Briggs and Brunson seek relief from alleged discrimi

nation in the providing of school facilities. While Briggs

is still on the district calendar the issue as to whether a

class action under Rule 23(a) (3) is presented here in

Brunson. On that issue, however, it is important to see

what the Court has said in Briggs.

On remand from the Supreme Court, the District Court

thus stated the “governing constitutional principles” for

the guidance of the Summerton trustees:

Having said this, it is important that we point ou'

exactly what the Supreme Court has decided and wha

it has not decided in this case. It has not decided ths

the federal courts are to take over or regulate the pu-

lic schools of the states. It has not decided that te

states must mix persons of different races in te

schools or must require them to attend schools or mst

deprive them of the right of choosing the sch>ls

they attend. What it has decided, and all iat

it has decided, is that a state may not deny tomy

person on account of race the right to attend any siool

that it maintains. This, under the decision othe

Supreme Court, the state may not do directly oindi-

rectly; but if the schools which it maintains aropen

to children of all races, no violation of the Constfition

is involved even though the children of differerffaces

voluntarily attend different schools, as they attd dif-

8 Briggs V. Elliott, 98 F. Supp. 529 (1951); 342 U. S. 350 (195,103 F.

Supp. 920 (1952); 347 U. S. 483 (1954); 349 U. S. 294 (1955); i f 7- Supp.

776 (1955).

Bobby Brunson, et al. v. Board of T rustees, et al.

ferent churches. Nothing in the Constitution or in

the decision of the Supreme Court takes away from

the people freedom to choose the schools they attend.

The Constitution, in other words, does not require in

tegration. It merely forbids discrimination. It does

not forbid such segregation as occurs as the result of

voluntary action. It merely forbids the use of govern

mental power to enforce segregation. The Fourteenth

Amendment is a limitation upon the exercise of power

by the state or state agencies, not a limitation upon

the freedom of individuals. 132 F. Supp. 766, 767

(1955).

Admittedly the constitutional right of equal protection

is a personal individual right which the person entitled

thereto may enforce or waive as he sees fit. No one else

can enforce it for him. “ It was as an individual that he

was entitled to the equal protection of the laws. . . .” Mis

souri, ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337, 351; Mc-

Laurin v. Oklahoma, 339 U. S. 637, 642. McCabe v. Atche-

son, 235 U. S. 151, Mitchell v. U. S., 313 U. S. 80, Hender

son v. U. S., 339 U. S. 816, International Machinists v.

Street, 367 U. S. 740, 774. Indeed the “ spurious” class

action authorized by the third subdivision of Rule 23 (a)

which the plaintiffs here invoke applies only where the right

of each member of the class is “ several.” The class action

joinder is allowed only when there is “ a common question

of law or fact.”

When the Supreme Court in the companion cases (of

which Briggs v. Elliott was one), generally cited as Brown

v. Board, 347 U. S. 483 (1954); 349 U. S. 294 (1955), de

cided that a state could not satisfy its obligation to provide

equal protection by requiring pupils of different races to

seek education in separate public schools, it invalidated

South Carolina laws to the contrary. In so doing it resolved

any question of law common to the several plaintiffs. In

fact, in limiting relief to the “ parties to these cases” (349

U. S. 301), the Court ended the availability of the spurious

8 Bobby Brunson, et al. v. Board of T rustees, et al.

class action insofar as this school district is concerned.

There is left for decision only the factual question of

whether the school trustees have, in assigning one of the

plaintiffs, deprived him of equal protection. This factual

question depends on many non-racial criteria and must be

resolved separately as to each pupil asking reassignment.

Shuttleworth v. Birmingham, 358 U. S. 101 (1958).4

On remand the District Court held that the common ques

tion of law had been resolved in the Briggs litigation and

since this last order of the District Court spelled out the

rights and obligations of the parties there is no unresolved

common question of law present in the Brunson case. (17a).

Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F. Supp. 776-777 (1955). Confirma

tion is found in the order dissolving the three-judge district

court in Davis v. Prince Edward, 142 F. Supp. 616, 619.

As we read plaintiffs’ brief it does not question the cor

rectness of our view that the common question of law (sep

arate schools vel non) has been resolved by the decisions in

Briggs v. Elliott, supra. Seemingly it claims that the ade

quacy of the administrative remedy provided in South Car

olina raises a common question of law justifying a spurious

class action.

In order to assure to every child aggrieved by his assign

ment to a particular school an adequate administrative

remedy for the resolution of his request for a different as

signment, South Carolina provides an appropriate proce

dure. 1952 Code 21-230 (9), 21-247. (21a-22a) Hood

v. Board, 232 F. 2d 626, 286 F. 2d 236.5 The plaintiffs’

brief seems to recognize that this procedure is fair and ade

4 Circuit Judge Tuttle recognized the applicable principle in Reddix v.

Lucky, 252 F. 2d 930, 938 (5th Cir 1958), where he said: “We think this

is not a proper case for a class action. Obviously the right of each voter

depends upon the actions taken with respect to his own case.”

'T h e South Carolina procedure is similar to that of North Carolina which

has been sustained here in numerous cases. Carson v. Board, 227 F 2d 789

Carson v. Warlick, 238 F. 2d 724, c. d., Covington v. Edwards, 264 F. 2d 78o’,

Holt v. Raleigh, 265 F. 2d 98, c. d. The Supreme Court has found that such

administrative procedures are valid in the field of pupil placement Shuttle-

worth v. Birmingham, 358 U. S. 101 (1958) affirming 162 F. Supp. 372.

Bobby Brunson, et al. v . Board of T rustees, et al. 9

quate on its face and that this Court has so ruled in Hood.

(Brief 10, footnote 2.)

The question of whether school trustees will fairly admin

ister such a statute cannot be reached under a complaint

asserting that the plaintiffs “have not exhausted the admin

istrative remedy provided by the South Carolina School

L a w s ....” (9a)

In the administration of the Buies of Civil Procedure it

was contemplated that the District Courts would exercise

broad discretion in applying these rules and that discretion

will not be disturbed here unless there is an abuse. This

policy of leaving the application of the rules to district

courts is particularly appropriate in the field of permissive

joinder contemplated by Rule 23(a) (3). Martinez v. Mav

erick, 219 F. 2d 666, 673 (5th Cir.) ; Kansas City v. Wil

liams, 205 F. 2d 47 (8th Cir.), c. d.®

Finally, it should be borne in mind that it is the District

Court to whom the Supreme Court entrusted the review of

school board action in applying the principles of Briggs v.

Elliott, 349 U. S. 294, 299. This is so because “ of their

proximity to local conditions.” It is obvious that the gov

erning constitutional principles must be applied differently

to a rural school district where the Negro school children

are a majority of eight to one, than in a cosmopolitan com

munity like Norfolk or Baltimore or New Orleans or to an

area where the Negro is a small minority.

The reasoning of the Court in Brown v. Board, 347 U. S.

483, 493-4, is that state law requiring the racial minority

to go to a school separate from the majority may create in

the members of this minority an inferiority complex, there

fore such law deprives the members of the minority of equal

protection. Here we have members of the majority race

attempting through the prayer of this class action to force

_8 The District Court’s discretion here is similar to that exercised under

kindred rules 42, 20, 22, 24. Collins v. Metro-Goldwyn, 106 F. 2d 83, 85,

Bedser v. Horton, 122 F. 2d 406, 407 (4th Cir. 1941), Gillette v. Northern

Oklahoma, 179 F. 2d 711 (10th Cir. 1950), Davis v. Yellow Cab Co., 220

F. 2d 790 (5th Cir. 1955), Whiteman v. Pitrie, 220 F. 2d 914 (5th Cir. 1955).

10 Bobby Brunson, et ai. v . Board of T rustees, et al.

the minority to be engulfed in the eight to one majority.

Such relief ( lOa-lla) would necessarily injure the person

ality of the minority and so deprive them of equal protec

tion.

As stated above, this is the school district before the

Court in Briggs v. Elliott, supra. 347 U. S. 495. In the

opinion filed May 31, 1955, the Court stated:

Full implementation of these constitutional principles

may require solution of varied local school problems.

School authorities have the primary responsibility for

elucidating, assessing and solving these problems;

courts will have to consider whether the action of school

authorities constitutes good faith implementation of

the governing constitutional principles. Because of

their proximity to local conditions and the possible

need for further hearings, the courts which originally

heard these cases can best perform this judicial ap

praisal. 349 U. S. 249.

On remand the three judge District Court, on July 15,

1955, in an opinion intended for the guidance of the trus

tees of the school district here involved, after observing

that “ no violation of the Constitution is involved even

though the children of different races voluntarily attend

different schools,” and that the Constitution [and, of course,

the Court] “ does not forbid such segregation as occurs as

the result of voluntary action,” but “merely forbids the use

of governmental power to enforce segregation,” filed an

order pursuant to the mandate from the Supreme Court in

which the defendants were “ enjoined from refusing on ac

count of race to admit to any school under their supervision

any child qualified to enter such school.” 132 F. Supp.

777, 778.

The problem of desegregation in this school district, while

not unique, was and is as difficult of solution as any in the

country. Without the understanding and cooperation of

the parents of both races in the district, it appeared in

Bobby Brunson, et al. v. Board of Trustees, et al. 11

surmountable. There was no immediate crisis because the

parents of the district continued to send their children to

the schools which they were attending, and to enroll new

students in the schools in which they would formerly have

been enrolled.

It thus appears that the trustees were warranted in per

mitting the parents of the district to continue voluntarily to

patronize its schools as they had in the past. In the mean

time, the placement procedure amended in 1956 provided

an efficient remedy to any who claimed the personal right

to attend a different school.

The three schools which the Negro children continued to

attend were and are the largest, the last constructed, and

most modern in the district. In location they cover the dis

trict’s area. By means of these schools the Negro school

children of the district have been receiving educational ad

vantages apparently still satisfactory to the overwhelming

majority of the Negro parents. The one white school is

smaller, older and located in the town of Summerton. The

majority of the white school children live in the town, and

nearer this school. The other three are more conveniently

located for the greater number of the Negro children.

Under the three judge Court’s order dated July 15, 1955,

the district’s school authorities were warranted in contin

uing to operate the schools as they had theretofore been

operated, in accordance with the demonstrated wishes of

the parents, and in relying upon the State’s placement pro

cedure legislation to afford an effective remedy for any

who claimed the right to attend another school. Such rem

edy has not as yet been invoked by a single school child or

parent, not even by the plaintiffs.

The District Judge, under these circumstances, was not

required to entertain another class action attack upon the

district’s school system; and his holding that the personal

rights claimed by the several plaintiffs should be asserted

by them severally and not jointly finds abundant support

in the history of the past litigation.

12

CONCLUSION

We submit that this cause is not a final judgment now

i eviewable here. Therefore the appeal should be dismissed.

In the alternative we ask affirmance.

DAVID W. ROBINSON

ROBINSON, McFADDEN & MOORE

Columbia, South Carolina

Attorneys for the Appellees

September 1962

Bobby Brunson, et al. v. Board of T rustees, et al.

21a

APPENDIX

Code of Laws of South Carolina 1952

Section 21-230. General powers and duties of school trus

tees.

The board of trustees shall also:

# * • * # * #

(9) Transfer pupils and designate schools attend.

Transfer any pupil from one school to another so as to

promote the best interests of education and determine the

school within its district in which any pupil shall enroll.

Section 21-230.2 Rules and regulations; hearings.

The boards of trustees of the several school districts may

prescribe such rules and regulations not inconsistent with

the statute law of this State as they may deem necessary

or advisable to the proper disposition of matters brought

before them. This rulemaking power shall specifically

include the right, at the discretion of the board, to desig

nate one or more of its members to conduct any hearing

in connection with any responsibility of the board and to

make a report on this hearing to the board for its deter

mination.

Section 21-247. May appeal decision of trustees to county

board of education.

Subject to the provisions of §21-230, any parent or per

son standing in loco parentis to any child of school age,

the representative of any school or any person aggrieved

by any decision of the board of trustees of any school dis

trict in any matter of local controversy in reference to the

construction or administration of the school laws or the

placement of any pupil in any school within the district

may appeal the matter in controversy to the county board

of education by serving a written petition upon the chair

man of the board of trustees, the chairman of the county

board of education and upon the adverse party within ten

22a

days from the date upon which a copy of the order or

directive of the board of trustees was delivered to him by

mail or otherwise. The petition shall be verified and shall

include a statement of the facts and issues involved in the

matter in controversy.

Section 21-21*7.2. Hearing; dispose of each school age

child separately.

The parties shall be entitled to a prompt and fair hearing

by the county board of education which shall try the matter

de novo and in accordance with its rules and regulations.

The county board of education may designate one of its

members to conduct the hearing and report the matter to

it for determination. When individual children of school

age are involved in the matter in controversy, the case of

each child shall be heard and disposed of separately.

Section 21-21*7.3. Appearance of parties; evidence.

At any such hearing the parties may appear in person

or through an attorney licensed to practice in this State and

may submit such testimony, under oath, or other evidence

as may be pertinent to the matter in controversy.

Section 21-21*7.1*. Decision of board; service.

After the parties have been heard, the county board of

education shall issue a written order disposing of the mat

ter in controversy, a copy of which shall be mailed to each

of the parties at interest.

Section 21-21*7.5. Appeal from decision of board to circuit

court.

Any party aggrieved by the order of the county board

of education may appeal to the court of common pleas of

the county by serving a written verified petition upon the

chairman of the county board of education and upon the

adverse party within ten days from the date upon which

copy of the order of the county board of education was

mailed to the petitioner. The parties so served shall have

23a

twenty days from the date of service, exclusive of the date

of service, within which to make return to the petition or

to otherwise plead, and the matter in controversy shall be

tried by the circuit judge de novo with or without reference

to a master or special referee. The county board of edu

cation shall certify to the court the record of the proceed

ings upon which its order was based and the record so cer

tified shall be admitted as evidence and considered by the

court along with such additional evidence as the parties

may desire to present. The court shall consider and dis

pose of the cause as other equity cases are tried and dis

posed of, and all parties at interest shall have such rights

and remedies, including the right of appeal, as are provided

by law in such cases.

lb

IN THE

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 8727

BOBBY BRUNSON, et al, A ppellants,

versus

BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 1

OF CLARENDON COUNTY, SOUTH CAROLINA,

et A ppellees.

A ppeal from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of South Carolina,

Charleston Division

MOTION TO DISMISS APPEAL

The defendants move that this appeal be dismissed be

cause the order from which the appeal is taken is not a

final decision within the meaning of 28 U. S. C. A. 1291

and is not the type of interlocutory order from which an

appeal may be taken under 28 U. S. C. A. 1292.

September 1962

DAVID W. ROBINSON

ROBINSON, McFADDEN & MOORE

Columbia, South Carolina

Counsel for the Defendants