Plaintiffs' Proposed Findings, Conclusions and Order on Detroit-Only Desegregation Plans

Public Court Documents

March 24, 1972

15 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Plaintiffs' Proposed Findings, Conclusions and Order on Detroit-Only Desegregation Plans, 1972. b2b52e19-53e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ded11795-fbbf-49e3-afa6-4e68a59af5ca/plaintiffs-proposed-findings-conclusions-and-order-on-detroit-only-desegregation-plans. Accessed February 14, 2026.

Copied!

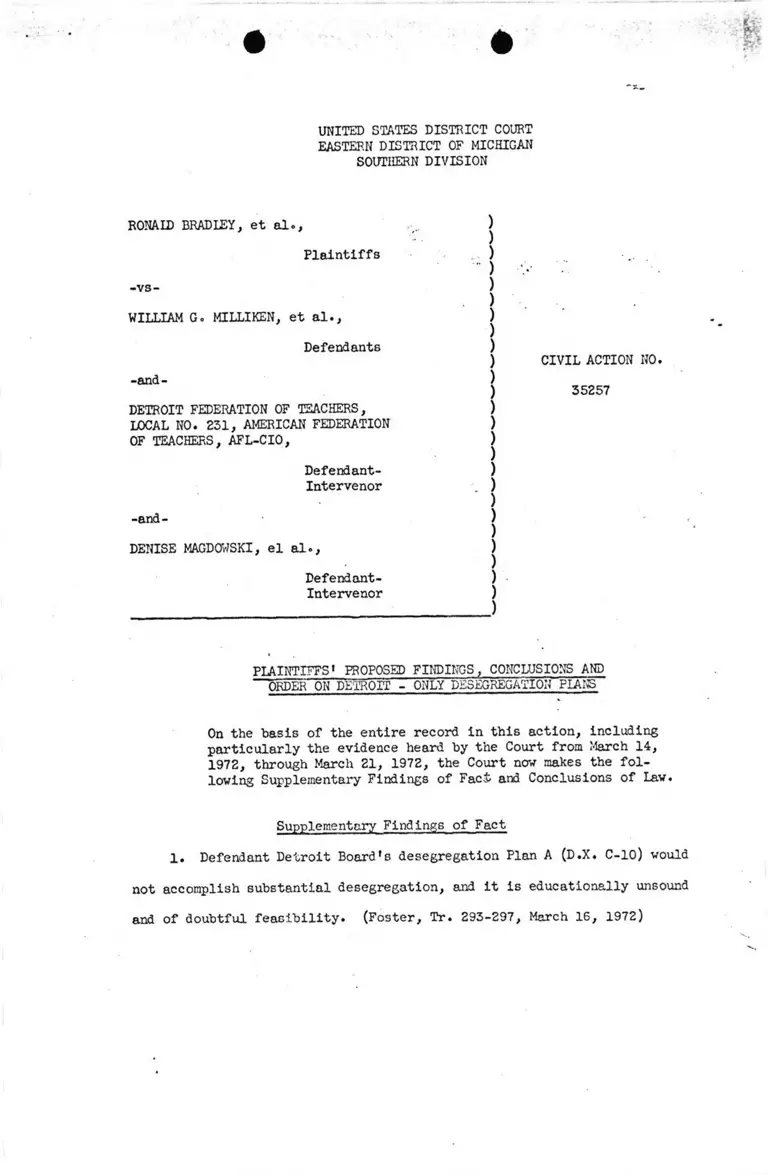

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

RONAID BRADLEY, et al.,

Plaintiffs

-vs-

WILLIAM Go MILLIKEN, et al.,

Defendants

-and-

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS,

LOCAL NO. 231, AMERICAN FEDERATION

OF TEACHERS, AFL-CIO,

•and

Defendant-

Intervenor

DENISE MAGDOWSKI, el al.,

Defendant-

Intervenor

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

. )

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

CIVIL ACTION NO.

35257

PLAINTIFFS* 1 PROPOSED FINDINGS, CONCLUSIONS AND

ORDER ON DETROIT - ONLY DESEGREGATION PLANS

On the basis of the entire record in this action, including

particularly the evidence heard by the Court from March 14,

1972, through March 21, 1972, the Court now makes the fol

lowing Supplementary Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law.

Supplementary Findings of Fact

1. Defendant Detroit Board’s desegregation Plan A (D.X. C-10) would

not accomplish substantial desegregation, and it is educationally unsound

and of doubtful feasibility. (Foster, Tr. 293-297, March 16, 1972)

1.1 Detroit's experience, like that of school systems elsewhere, has

been that freedom of choice, student option plans, and controlled transfer

have been ineffective as desegregation devices. (Foster, Tr. 295-296,

March 16, 1972; Progress Report, November 1, 1971, p. 16; McDonald, Tr.

70-72, March 14, 1972) . - -

lo2 At the high school level, Plan A proposes an enhanced version of

the specialized curriculum model which was an almost total failure, as a

desegregation plan, during 1971-72. (McDonald, Tr. 57, March 14, 1972;

Progress Report, p. 13-16; Foster, Tr. 295, March 16, 1972) No witness

for the Detroit Board was able to assure the Court that desegregation at

the high school level would be significantly improved under Plan A.

(Rankin, Tr. 598, 613, 650-651; McDonald, Tr. 61, 83, 85, 90-91, March 14,

1972; D.X. C-ll, pp. 1-2)

1.3 At the magnet middle school level, grades 3 to 8, Plan A could

affirmatively affect only 20,000 of the approximately 140,000 students in

those grades, and one side-effect has been in 1971-72, and would be,.to

intensify segregation at other schools. (Rankin, Tr. 608, 612, 615,

March 21, 1971; D.X. C-ll, p. 5; Progress Report, /Appendix, Individual

Magnet Middle Schools Transfer Reportsj) ■

1.4 The magnet middle schools component of Plan A would set up a

limited number of greater resource schools, which would be attended by a

higher proportion of the white students- in those grades, and would, by

virtue of the 50/50 or 60/40 (black/white) racial quota system, assign a

higher proportion of black students at those grade levels to lesser resource

schools. (McDonald, Tr. 98, March 14, 1971; Rankin, Tr. 607, March 21, 1971)

Such arrangements were characterized by an expert witness for the plaintiffs

as educationally unsound and by an expert witness for the Detroit defendants

as unconstitutional. (Foster, Tr. 294, 296, March 16, 1972; Guthrie, Tr.

491, March 17, 1972)

•• 2 -

would affect not more than 40,000 children on a part-time basis (approxi

mately 40 percent, at most, of their school time). Its additional cost would

approximate the additional transportation costs roughly projected for

plaintiffs' 12-grade desegregation plan. (Compare D.X. C-12, p. 3 with

Foster, Tr. 346, March 16, 1972) A variation of this Plan, also limited to

grades 3 to 6, would involve partial pairing of elementary schools for

humanities programs. - -

Such programs may be educationallj1' innovative or otherwise attractive, *

but none of the testimony on behalf of any party supported Plan C as

effective to accomplish desegregation. The Defendant Detroit Board preferred

Plan A, and, in addition to the part-time desegregation feature, it is

undisputed that Plan C would leave the "base" schools no less racially

identifiable (80 percent or more black or white, according to D.X. C-12;

and see Rankin, Tr. 616-618, March 21, 1972) than they are today. In ,

addition, the school pairing variation, by its 50/50 racial quota, would

apparently, as In the case of magnet middle schools in Plan A, assign a

disproportionate number of black pupils to nonspecial schools at grades

3 to 6. .•

The Court agrees on this question with Detroit Board member McDonald who

testified (McDonald, Tr. 50, March 14, 1972); "i don't'think that that

would accomplish the goal of either integration or desegregation." That

was also the testimony of plaintiffs' expert, Dr. Gordon Foster, and the

Court so finds. (Foster, Tr. 297-298, March 16, 1972)

3. The Court finds that neither of the defendant Detroit Board's

plans, A or C, would accomplish a significant amount of school desegregation

in the Detroit district. The Court further finds that both plans are

educationally less sound than available alternatives, including metropolitan

desegregation, and that Plan A, which is more specifically developed than

Plan C, is economically less feasible than available alternatives, including

plaintiffs' Plan. (Compare McDonald, Tr. 100, March 14, 1972; with Foster,

Tr. 346, March 16, 1972.)

- 4 -

4. Plaintiffs have also submitted to the Court a desegregation plan

(PC-2, PC-3), which has been the subject of considerable testimony. (Foster,

Tr. 302-348, March 16, 1972)

4»1 Measured by the numbers of black and white Detroit pupils who would

attend schools together, it is undisputed that plaintiffs’ plan would

accomplish more desegregation of the Detroit school system than now obtains

v •• -

or than would be achieved by any other plan proposed. (Rankin, Tr. 594, 596-7,

March 21, 1972; McDonald, Tr. 49, March 14, 1972) __

4.2 Although the advisability of implementing plaintiffs’ plan for

September of 1972, if a substantially different plan were to follow shortly

thereafter, was challenged, the preponderance of the evidence is clearly to

the effect that, assuming the availability of the necessary pupil transpor

tation equipment, it would be administratively feasible to implement plaintiff

plans for September of 1972o (Foster, Tr. 347-348, March 16, 1972; Guthrie,

Tr. 498, March 17, 1972)

4.3 Plaintiffs’ expert testified that if a plan must be limited to

Detroit, his plan is educationally sound and should be implemented in

preference to continuing the present segregation and the Court so finds.

■ 3G4- -7£5>3^,40l .

(Foster, Tr. 299-301, 312,348, 350-351, _375,jMarcb 16, 1972; Cf. Guthrie,

Tr. 498-9, March 17, 1972) The Detroit defendants have strongly challenged

plaintiffs' plan, but neither they nor any other party has presented to the

court assertedly preferable plans that could accomplish equivalent desegre

gation.

4.4 The defendants* criticism of plaintiffs’ plan may be summarized

as follows: (a) it fails to upgrade the socioeconomic status (SES) of

Detroit schools, which is an important determinant of educational quality;

(b) virtually all schools would be majority black, which would accelerate

white flight to the suburbs; (c) suburban children, mostly white, will

continue to be denied the benefits of school desegregation; (d) racial

tensions are most acute among lower SES children, so a desegregation plan

limited to such children would result in greater social friction than would

a plan involving a higher percentage of higher SES children; and (e) it

would be administratively imprudent to implement plaintiffs* plan if a

metropolitan desegregation plan, which would involve another round of adminis

trative changes, is to be adopted thereafter. (Rankin, Tr. 572-589, 620-626,

March 21, 1972; Guthrie, Tr. 461-474, March 17, 1972)

One of the defendants’ experts, Dr. Rankin, agreed that, given the

present degree of segregation in Detroit and the correlation between black

and lower SES, an intra-Detroit plan would increase somewhat the SES status

of schools attended by black children. That is, there would be a leveling

effect, but he also testified that in his opinion the increase would be

educationally insignificant. (Rankin, Tr. 620-623, March 21, 1972) Dr.

Rankin also testified that SES considerations were not a factor in the

preparation of Detroit’s own plans, and that the loss of benefits to suburban

children would be true of any plan limited to Detroit. (Rankin, Tr<> 63o-4,

March 21, 1972)

' The defendants' criticisms of plaintiffs' plan were almost entirely in

comparison to a metropolitan plan. Dro Guthrie did testify that he would

hesitate to desegregate a majority black, lower SES district because the

educational benefits at least in the achievement sense, would be dubious;

but he also testified that he would move to remedy segregation resulting

from illegal acts and practices wherever it exists. (Guthrie, Tr. 487,

443-4, 499-500, March 17, 1972)

Dr. Foster testified that the concept used in plaintiffs’ plan could

well be compatible with a metropolitan plan. (Foster, Tr. 348-350, March

16, 1972) While there would be substantial administrative changes and pupil

reassignment should a metropolitan plan of desegregation subsequently be

entered, Dr. Foster testified, and the Court so finds, that implementation of

plaintiffs' plan as an interim plan would provide educational benefits and

would be preferable to continuing the present segregation for another year.

(Foster, Tr. 340-350, March 16, 1972)

6

4o5 The defendants' transportation expert testified that new trans

portation equipment would be available for the fall, 1972 term if ordered

in March or April. Plaintiffs* experts testified that such an order should

be placed immediately. (Kuthy, Tr. 134, 144, 155, March 15, 1972; Smith,

Tr. 420, 439, 442, March 17, 1972; see also Foster, Tr. 383-384, March 16,

1972) On the basis of the present record, the Court finds that the new

transportation equipment needed to implement plaintiffs’ plan in September ,

of 1972 can be secured.

4.6 Plaintiffs* witness Foster estimated that the annual additional,

cost to the system for new transportation would be somewhat over 4 million

dollars (including amortization for capital expenditures) 2 percent or less

of.the District’s annual budget, and that the amount would be lower if buses

averaged more than two trips (which would be feasible and not uncommon) or if

kindergarden children were omitted from his plan. (Foster, Tr. 346, March

16, 1972) Plaintiffs' witness Smith's testimony indicated a lower cost

figure based upon his computation which involved more children per bus and

fewer new buses. (Smith, Tr. 417, March 17, 1972) The testimony also

indicated that, to some extent, the existing facilities of the local public

transit company (DSR) could be used and meshed with ne\r[ school busing, thus

reducing at least new capital costs still further. (Smith, Tr. 420-421,

March 17, 1972; Foster, Tr. 383, March 16, 1972)

The foregoing testimony was largely uncontroverted, and on the present

record, the Court finds it to be factual.

4.7 Taken as a whole, the testimony concerning pupil transportation

established that it is a long standing, educationally sound practice and

safer than walking to school. (Smith, Tr. 408-409, March 17, 1972; Kuthy,

Tr. 140, 156-157, March 15, 1972) There are limits on the times and distance

that children at various ageB should be transported, but nothing in the record

suggests that the additional transportation involved in plaintiffs' plan

- 7 -

' • •

(or those of the defendants) would approach such limitations, and the Court

bo finds. (Foster, Tr. 333-334, March 16, 1972) The Court also finds, as

testified by defendants* expert Kuthy, that a metropolitan pupil transpor

tation system, including Detroit, would be more economical and administra

tively more feasible than parallel systems in Detroit and its suburbs.

(Kuthy, Tro 134-136, 181, 184-187, 195-196, March 16_, 1972) •

4o8 There is a dispute among the parties about the amount of new

transportation equipment required to accomplish the desegregation called for*.

in plaintiffs’ plan. Basically, the disagreement is a function of whether

or not an average of 2 or 3 trips per bus may be routed and accomplished

under such plan. (Kuthy, Tr. 102-124 , March 16, 1972; Smith, Tr. ^|7j^3£>

March 17, 1972) The need for new transportation equipment might further

vary depending on the degree to which DSR faculties and present routes could

be utilized, the staggering of school openings, the acquisition of a yellow

bus fleet for the city of Detroit, the joint utilization by Detroit and suburban

districts of existing yellow bus equipment, and/or a combination of any of the

above.

4.9 Defendants’ expert Kuthy testified that it would take five months

to design for Detroit a 75,000 pupil transportation plan, and several

months thereafter to make it smoothly operational. (Kuthy, Tr. 188-189,

March 16, 1972) Plaintiffs’ expert Smith estimated six to ten weeks for

'designing such a plan, with a short period in September to iron out opera

tional details. (Smith, Tr. 418-419, 439-441, March 17, 1972) Based upon

the experience of newly desegregating systems elsewhere, Dr. Foster also

223-3^^-thought Mr. Kuthy’s estimate too long. (Foster, Tr. 347-24^/, March 16, 1972)

The Court finds that, even by the most pessimistic estimate, it would be .

practicable to prepare and implement for September a design for the trans

portation that would be involved in plaintiffs' plan. The Court also finds

that, while five months of design time might be desirable, the task could be

done effectively in a shorter period.

- 8 -

5. Defendants’ expert Dr. Guthrie testified that there is a fairly high

correlation between race and SES, i.e. black families are proportionately

somewhat more likely to be lower SES, because of wide ranging prior racial

discrimination in our society. He testified that school desegregation plans

that give appropriate consideration to SES factors are educationally

beneficial, in the achievement and associational senses, for all children.

He also testified that programs which would infuse large amounts of money

and educational resources into racially isolated, lower SES schools would not

be educationally productive, in the achievement or associational sense,

compared to a sound plan of desegregation. Neither Dr. Foster nor any other

witness expressed substantial disagreement with these views. (Guthrie,

Tr. , March 17, 1972)

The Court finds that compensatory education alone is inadequate to

correct the educational disadvantages of segregated education. The Court

further finds that, although it may not be constitutionally required, school

authorities may give due regard in formulating a plan of desegregation to

factors such as SES, however, consideration of such factors may not be used

to delay, impede, limit or frustrate the timing or the degree of actual

desegregation.

6. In any pairing, clustering or grouping of schools, grade structures

are altered; appropriate, and substantial reassignment of faculty is there

fore necessitated. ( R*vakiv\ ̂ Tr. 2 1 ) 1972. ) Moreover,

all experts agreed that simultaneous desegregation of faculty is educationally

sound and an important part of any plan of school desegregation. (Foster,

Tr. 312, 353, March 1972; Guthrie, Tr. 495-6, March 17, 1972; Rankin, Tr.

, March 21, 1972. See also Detroit Board "Basic Guidelines for

a Metropolitan Detroit Aj-ea Plan, p. 33; Metropolitan School District

Reorganization Plan, p. 20; Metropolitan One-way Student Movement and

Reassignment Plan, p. 22) .

- 9 -

r...

7. The Defendant Detroit Board selected, and submitted to the Court,

Plans A and C while rejecting alternative plans which would have achieved

a greater degree of actual desegregation. See, e.g., Modified Feeder Plan

C, which subsequently was developed in plaintiffs' plan. (PC-2, 3). The

default of the Board in submitting plans which previously had failed or were

not reasonably calculated to produce meaningful actual desegregation in light

of the available alternatives constitutes legal bad faith. (See Green v.

New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430(1968)). The preparation of a plan by plaintiffs

was required by the default of the Detroit Board of Education. Expenses

incurred by plaintiffs in preparation of such plan were necessitated by that

default.

- 10 -

Supplementary Conclusions of Lav

1. This court has continuing jurisdiction of this action for all

purposes, including the granting of effective relief. Ruling on Issue of

Segregation, September 27, 1971; Raney v. Board of Education, 391 U.S.

443(1968). ' • y /. ' .

2. On the basis of the Court’s prior finding of illegal school

segregation, the obligation of the defendants is to adopt and implement an y

educationally sound, practicable plan of desegregation that promises

realistically to achieve now and hereafter the greatest possible degree of

actual school desegregation. Green v. County School'Board, 391 U.S. 430(1968);

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education, 396 U.S. 19(1969); Carter v.

West Feliciana Parish School Board, 396 U.S. 290(1970); Swann v. Charlotte-

Mecklenberg Board of Education, 402 U.S. l(l97l); Davis v° Board of School

Commissioners, 402 U.So 33(l97l).

3. Defendant Detroit Board’s Plans A md C are legally insufficient

because, compared to existing alternatives, they do not promise to effect

significant desegregation. Green v. County School Board, supra, at 439-440;

U.S. v. Jefferson County Board of Education, 372 F.2d 836, 895-96(5th Cir.

1966); U.S. v. School District 151, 301 F.Supp. 201, 232-33(N.D.111., 1969);

Bivins v. Bibb County, 424 F.2d 97(1970). In Addition, to the extent that plans

A and C would maintain extra-resource schools which would be attended, on

the basis of race, by a higher proportion of the total white children, while

maintaining lesser resource schools which would be attended on the basis of

race by a high proportion of the total black children, they are prima facie

unconstitutional. Brown v. Bd. of Educ.,547 U.S. 483(1954); Hobson v. Hansen,

269 F.Supp. 40l(D.D.C. 1967); Brunson v. Bd. of Trustees, 429 F.2d 820

(4th Cir. 1970). _

- 11 -

4. The omission from the Detroit defendants' plans of kindergarden and

grades 1 and 2 is another factor in their legal insufficiency. And as indicated

in the Findings of Fact, above, the cost estimates associated with plan A

render it less practicable than existing alternatives. U.S, v. School District

151, 301 FoSupp. 201, 233(NoDoIllo, 1969); Price v. Denison School District,

348 F.2d 1010, 1012(5th Cir. 1965).

5. The adoption and implementation of an existing educationally sound

practicable plan may not be postponed upon the contingency that something

better may turn up. U.S. v. Baldwin County Board of Education, 423 F.2d

1013(5th Cir. 1970); Bradley v. Richmond School Board, 325 F.Supp. 828(E.D.VA.

1970); U.S. v. Bdo of Trustees, 424 F»2d 625, 627(5th Cir. 1970).

6. Community opposition to school desegregation, manifested by white

flight or otherwise, is an impermissible basis for limiting the requirement

of desegregation or the effectiveness of plans. Monroe"v. Bd. of Commissioners,

391 U.S. 450, 459(1968); Cooper Vo Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, 13(1958).

7. Factors such as racial tensions and socioeconomic (SES) composition

of schools may be relevant to evaluating the educational soundness and

practicability of alternative, equally effective desegregation plans. But,

the constitutionally required remedy for racial segregation is racial desegre

gation; and particularly as such factors are the legacy of prior segregation

- 12 -

and discrimination, they may not be the basis for limiting the actual

effectiveness of desegregation plans. Swann, supra, 91 S.Ct. 1267, 1280

Note 8; Brunson v. Bd. of Trustees, supra; U.S. v. School District 151,

supra, 301 F.Supp. at 231; Brewer v. Norfolk School Board, 434 F„2d 408, 411

(4th Cir. 1970).

8. Measured by the legally permissible considerations, plaintiffs’

plan is the only effective, educationally sound, practicable plan before the

Court, and the defendants should, pending further litigation, undertake all ..

necessary steps preparatory to implementing it for September 1972. Carter v.

West Feliciana Parish School Bd., supra.

9. This Court reaffirms and readopts its prior Conclusions (See Ruling

on Issue of Segregation, Sept. 27, 197l) that the state of Michigan is

constitutionally responsible for securing to all its children, including the

children of Detroit, equality of educational opportunity free from racial

segregation and discrimination. The Court also reaffirms that certain of

the state’s acts and practices were causal factors in the racial segregation

in and of Detroit, inviolation of the Constitution. Bradley v. Milliken,

438 F.2d 945(6th Cir. 197l); Ruling on Issue of Segregation.

10. As indicated in the Findings of Fact, above, no Detroit-only plan

of desegregation will provide complete and adequate relief for the constitu

tional violations found in this case. This Court and school authorities

including state educational authorities, are obliged to seek and adopt the

best available plan. Swann, supra; Green, supra; Carter, supra; Baldwin

County, supra. Considering the nature of the violation and the powers of

this Court, in both the jurisdictional and equitable sense, plans of metro

politan relief must be considered. See Bradley v. Richmond School Board _____

F.Supp. _____(C.A. 3353, decided January 5, 1972, E.D.VA.) and esses stated

therein. Moreover, the burden of coming forward with a sound, constitutionally

adequate plan remains with the defendants.

- 13

1 1 . As concluded above (No. 5), timely relief is imperative in this

action, and the asserted preferability of metropolitanism is not a basis for

continuing school segregation in Detroit. Therefore, unless the metropolitan

concept becomes a metropolitan plan for 1972-73, the Constitution requires that

plaintiffs’ plan, with appropriate final embellishments, be implemented.

Carter, supra; Baldwin County, supra.

12. In making reassignment of faculty nessitated by a system-wide

alteration of pupil assignments and grade structures, the defendant Detroit

Board and the State have the power and the continuing, present duty to insure

’ c r c r e A r l ' . r ja

that such faculty reassignment affirmatively avoids maintaining j th e racial

identification of schools "simply by reference to the racial composition of

teachers and staffo" Swann, 402 U.S. at 18. Moreover, the scope of the

Court’s equity power is broad and not limited to the precise contours of the

violation. Swann,402 UoS. at 15. Therefore, to the extent to which faculty

desegregation is essential to the effective implementation of a plan of pupil

desegregation, it may be so ordered. United States v. Montgomery County Board

of Educ., 395 U.So 225(1969). In either case no contract, union agreement or

otherwise, or Board policy or practice may impede Fourteenth Amendment

obligations. United States v. Greenwood Municipal Separate School District,

406 F .2d 1086, 1094(5th Cir.), cert, denied 395 U.S. 907(1969); Berry v.

Benton Harbor, _____F.Supp._____($.D.Mich. 1971).

13. The choice by school authorities of less effective alternatives puts

into question the "good faith" of school authorities. Green v, New Kent County,

391 U.S. 430(1968) Where school authorities choose, among alternatives,

that alternative whose natural, probable, forseeable, and reasonable effect

is to minimize desegregation, such action is intentional within the meaning

of the Fourteenth Amendment. Ruling on Issue of Segregation; Bradley v.

Richmond, slip opinion. .

Respectfully submitted,

ipAUL R. .DIMC ;5 7 ..

J. HAROLD FLANNERY .

ROBERT PRESSMAN

Center f or Law & EducatL on

Harvard University

Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138

LOUIS R. LUCAS

WILLIAM E. CALDWELL '

Ratner, Sugarmon & Lucas

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

NATHANIEL R. JONES

General Counsel, N.A.A.C.P.

1790 Broadway

New York, New York 10019

E. WINTHER HcCROOM

3245 Woodburn Avenue

Cincinnati, Ohio 45207

JACK GREENBERG

NORMAN J. CHACKKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Certificate of Service

I, Paul R. Dimond, of counsel for plaintiffs, hereby certify that I

have served the foregoing upon the defendants Detroit Board, state

officials, teachers association, and Denise Magdowski by mailing, postage

prepaid, copies to their counsel of record on'March .'- 24, 1972.

RJP.CL

PAUL R. DIMOND

J. HAROID FLANNERY

ROBERT PRESSMAN

Center for Law & Education

Harvard University

Cambridge, Mass. 02138