Beer v. United States Brief for Appellees Johnny Jackson, Jr. et al.

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1974

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Beer v. United States Brief for Appellees Johnny Jackson, Jr. et al., 1974. 1e69798a-c69a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/df88b638-ca52-4f05-b298-0584f7261fe9/beer-v-united-states-brief-for-appellees-johnny-jackson-jr-et-al. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Copied!

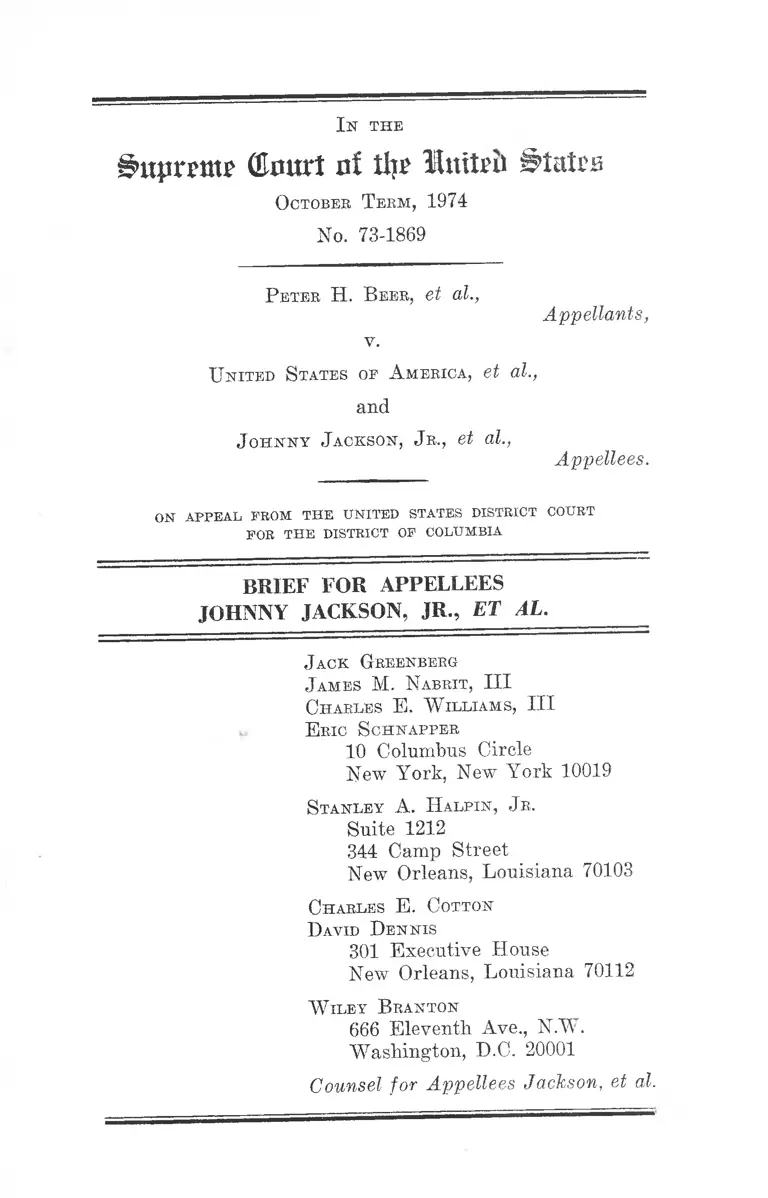

I n t h e

&upr?m? (Emtrt nf tlj£ HuitPi* States

O ctober T e e m , 1974

No. 73-1869

P eter H . B e e r , et al.,

Appellants,

v.

U n it e d S tates op A m erica , et al.,

and

J o h n n y J a ck so n , J r., et al.,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL PROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OP COLUMBIA

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

JOHNNY JACKSON, JR., ET AL.

J ack G reenberg

J am es M. N abrit , III

C h a rles E . W il l ia m s , III

E ric S c h n a p f e r

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

S ta n ley A. H a l p in , J r .

Suite 1212

344 Camp Street

New Orleans, Louisiana 70103

C h a rles E . C otton

D avid D e n n is

301 Executive House

New Orleans, Louisiana 70112

W il e y B ranton

666 Eleventh Ave., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20001

Counsel for Appellees Jackson, et al.

I N D E X

PAGE

Questions Presented .......... ........ -............................ -.... 1

Summary of Argument..... -............-.............................. 2

Argument ..................... 3

I. Plan II Would Have the Effect of Denying or

Abridging the Right to Vote on Account of Race

or Color ......................................................... 5

1. The Legal Standards......................................... 5

2. The Effect of Plan II ....... ...... . - ............... 14

II. Plaintiffs Failed to Prove That Plan II Did Not

Have the Purpose of Denying or Abridging the

Right to Vote on Account of Race........................ 22

C o n c lu sio n ............................ 27

T able of A u t h o r it ie s :

Cases:

Allen v. Board of Elections, 393 U.S. 544 (1968) .......... 4

Anderson v. Martin, 375 IJ.S. 399 (1964) ................. 20

Burnette v. Davis, 382 U.S. 42 (1965) ........................- 7

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) ..... 14

City of Petersburg v. United States, 410 U.S. 962

(1973) ........................................................................13,21

Connor v. Johnson, 11 Race Rel. Rep. 1859 (S.D. Miss.

1966) 8

11

PAGE

Connor v. Johnson, 265 F. Supp. 492 (S.D. Miss. 1967) 8

Fortson v. Dorsey, 379 TT.S. 433 (1965) ............ 7

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960) ...... 7

Katzenbach v. Morgan, 384 U.S. 641 (1966) ............ 11

Kilgarlin v. Hill, 386 U.S. 120 (1967) ........ ................... 7

Perkins v. Matthews, 400 U.S. 379 (1971) ________ 8, 9,10

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964) ......................... 19

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301 (1966) ....4,11

Taylor v. McKeithen, 499 F.2d 893 (5th Cir. 1974) ...... 12

United States v. Association of Citizens Councils of

Louisiana, 187 F. Supp. 846 (W.D. La. 1960) .......... 15

United States v. Georgia, 411 U.S. 526 (1973) ......... .10, 21

United States v. Louisiana, 380 U.S. 145 (1965) .......... 15

United States v. McElveen, 177 F. Supp. 355 (E.D. La.

1960) ........................................................................ 15

Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124 (1974) .....................7, 22

White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (1973) ........ .......... . 11

Wright v. Council of City of Emporia, 407 U.S. 451

(1972) .......................................................... ............... 13

Wright v. Rockefeller, 375 U.S. 52 (1964) ................... 7,12

Statutes and Constitutional Provisions:

United States Constitution, Fourteenth Amendment.... 11

United States Constitution, Fifteenth Amendment ..3,11, 21

Ill

PAGE

42 U.S.C. § 1973b (Section 4 of the Voting Eights Act) 3

42 U.S.C. § 1973c (Section 5 of the Voting Eights

Act) .................................... ......... -.............. ......... passim

La. Eev. Stat., Art. 18, § 358 .......................................... 20

Legislative Materials:

115 Cong. Eec. (1969) ................................................- 7

116 Cong. Eec. (1970) ................. ........................-.....— 6,7

Hearings Before a Subcommittee of the House Judi

ciary Committee, 94th Cong., 1st Sess., (1975) ......... 11

Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Constitutional

Eights of The Senate Committee on the Judiciary on

Bills to Amend the Voting Eights Act, 91st Cong.,

1st and 2d Sess., (1969-70) -................................ 7, 8, 9, 21

Hearings before Subcommittee No. 5 of the House

Committee on the Judiciary on H.E. 4249, 91st Cong.,

1st Sess. (1969) .................................. -........................ 6,8

Official Journal of the Constitutional Convention of the

State of Louisiana, 1898 ....................... .......... -......... 14

Other Authorities:

United States Commission on Civil Eights, The Voting

Eights Act: Ten Years After (1975) ............9,10,11,15

United States Commission on Civil Eights, Political

Participation (1968) ........................ .........-....5,6,7,8,15

PAGE

1961 United States Commission on Civil Rights Report:

Voting .................................. ............................... ......14,15

Hearings in Louisiana Before the U.S. Commission on

Civil Rights .................................................... ........... 14

David H. Hunter, Federal Review of Voting Charges:

How to Use Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act,

(1974) 9

I n t h e

§>ttpmnp OInurt of tl|p ImtrS i ’tairn

O ctober T e r m , 1974

No. 73-1869

P eter H . B e e r , et al.,

Appellants,

v.

U n it e d S tates of A m erica , et al.,

and

J o h n n y J a ck so n , J r ., et al.,

Appellees.

o n a p p e a l f r o m t h e u n it e d s t a t e s d is t r ic t c o u r t

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

JOHNNY JACKSON, JR., ET AL.

Questions Presented

1. Did plaintiffs prove that Plan II will not have the

effect of denying or abridging the right to vote on account

of race or color?

2. Did plaintiffs prove that Plan II did not have the

purpose of denying or abridging the right to vote on

account of race or color?

2

Summary of Argument

1. 1. Section 5 of the Voting Eights Act was adopted to

prevent states and subdivisions with a history of dis

crimination in voting from devising new schemes to disen

franchise minority voters. Section 5 was applied to re

districting laws because ordinary constitutional challenges

had proved ineffective in preventing the dilution of black

voting strength. Congress was concerned in particular to

forbid through section 5 the implementation of districting

plans which divided concentrations of black voters among

several predominantly white districts. Such plans are

impermissible under section 5 regardless of whether they

have a “rational basis.”

2. Plan II is precisely the type of districting plan which

section 5 was intended to prevent. The District Court

correctly concluded that black voters in New Orleans were

concentrated in an east-west belt. Plan II systematically

divided that black concentration among five different city

council districts with substantial numbers of white voters.

The adverse effect of this division on black voters was

aggravated by the pattern of bloc voting along racial lines

in New Orleans.

II. Plaintiffs failed to establish that Plan II was a good

faith effort to correct the undisputed defects in Plan I.

Plan II was prepared before the Attorney G-eneral objected

to Plan I, and necessarily failed to take into account the

nature of those objections. Plan II was fashioned to solve

problems regarding the predominantly white Algiers

section, and its effect on the fragmentation of the black

community was both incidental and largely insignificant.

Since Plan II was enacted by city couneilmen with a vested

interest in diluting the voting strength of the black com-

3

munity, and since Plan II had precisely that effect, the

conclusion is inescapable that such dilution was the purpose

of Plan II.

Argument

In 1965, after extensive hearings and debate, and in the

face of evidence that less drastic measures had proved

ineffective, Congress adopted the Federal Voting Rights

Act. The Act implemented Congress’ firm intention to rid

the country of racial discrimination in voting, and provided

stringent new remedies against those practices which had

most frequently denied citizens the right to vote on the

basis of race. The Act suspended for five (now ten) years

the use of certain “tests and devices” which Congress

believed had been adopted or administered so as to dis

criminate on the basis of race. 42 IJ.S.O. §1937b. Although

none of these tests or devices were unconstitutional per se,

this Court upheld the suspension as within the power of

Congress under section 2 of the Fifteenth Amendment.

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301, 333-34 (1966).

Congress was further concerned, however, that the mere

suspension of existing tests would not prove sufficient to

end the problems of discrimination that had existed for

decades in the covered states such as Louisiana. Some of

those states had in the past shown extraordinary ingenuity

in contriving new laws and procedures to perpetuate voting

discrimination, and Congress had reason to fear that those

states might resort to similar maneuvers in the future.

Under the compulsion of these unique circumstances, and

unable to foresee every discriminatory contrivance which

might in the future be concocted, Congress adopted section

5 of the Act. Section 5 requires that, prior to implementing

any “voting qualification or prerequisite to voting, or

4

standard, practice or prooednre with respect to voting

different from that in force or effect on November 1, 1964,”

the State or subdivision involved must obtain a declaratory

judgment in the United States District Court for the Dis

trict of Columbia that the new practice “does not have

the purpose and will not have the effect of denying or

abridging the right to vote on account of race or color.”

42 U.S.C. §1973c. Section 5 also establishes an alternative

and more expeditious procedure for obtaining approval of

the new law; the new law may be enforced if it is sub

mitted to the Attorney General of the United States and,

within 60 days of the submission, the Attorney General

does not formally object to the' new statute or regulation.

See South Carolina v. Katsenhach, 383 U.S. 301, 335

(1966); Allen v. Board of Elections, 393 U.S. 544, 548-49

(1968).

The subject of the instant action is Ordinance No. 5154

(hereinafter referred to as “Plan II”), which redistricts

the City Council of the City of New Orleans. Plaintiffs

submitted Plan II to the Attorney General in May, 1973;

on July 9, 1973, the Attorney General interposed an ob

jection to Plan II on the ground that plaintiffs had failed

to establish that the plan would not have the effect of dis

criminating on the basis of race.1 Thereafter plaintiffs

commenced this action in the United States District Court

for the District of Columbia, seeking a declaratory judg

ment that Plan II did not have the purpose and would

not have the effect of denying or abridging the right to

vote on account of race or color. On March 15, 1974, the

District Court concluded that Plan II would have such a

discriminatory effect, and denied the declaratory judg

ment.2 Having resolved the case on this basis, the Dis-

1 Appendix, pp. 33-35.

2 Jurisdictional Statement, pp. la-74a.

5

trict Court did not reach the question of whether Plan II

also had a discriminatory purpose.3

I.

Plan II Would Have the Effect of Denying or Abridg

ing the Right to Vote On Account o f Race or Color.

1. T he Legal S tandards

The legislative history of section 5, particularly in con

nection with the renewal of the Voting Rights Act in 1970,

makes clear the type of reapportionment with which Con

gress was concerned and which Congress adopted section 5

to stop—the division of a concentration of black voters

among several districts in which the black voters were

combined with a larger number of white voters. In 1968

the United States Civil Rights Commission reported to

Congress that district lines were being drawn in this way

in southern states to dilute the newly gained voting-

strength of Negroes.4 In Alabama state legislative dis-

stricts had been fashioned so that they “aggregated pre

dominantly Negro counties with predominantly white

counties,” thus “preventing election of Negroes to House

membership.” In Mississippi the congressional district

lines were drawn to divide the predominantly black Delta

region among three districts with white majorities.5 Senate

and House seats were also redrawn in Mississippi.

In several instances, the legislature combined counties

in which Negroes constituted a majority of the popula

tion and a majority of the registered voters in legis-

3 Jurisdictional Statement, pp. 40a-42a.

4 United States Commission on Civil Rights, Political Participa

tion, p. 177 (1968).

6 Id., p. 31.

6

lative districts with counties having white population

and voting majorities. For example, majority Negro

Claiborne County was joined in a senatorial district

with majority white Hinds County. Jefferson County,

with a 70 percent Negro population and a Negro voting

majority, was combined with Lincoln County, which

has a population 69 percent white. In both cases the

resulting district had a majority white population.6

The results of this 18 month Civil Rights Commission

study were among the factors that induced Congress in

1970 to extend the Voting Rights Act. See 116 Cong. Rec.

5521, 5526 (1970).

Concern with this problem was voiced throughout the

legislative process in 1970. At the House hearings Mr.

Glickstein of the Civil Rights Commission testified,

The history of white domination in the South has

been one of adaptiveness, and the passage of the

Voting Rights Act and the increased black registra

tion that followed has resulted in new methods to

maintain white control of the political process. . . .

For example, State legislatures [have redrawn] the

lines of districts to divide concentrations of Negro

voting strength.7

Congressman McCulloch expressed a similar concern with

the alteration of district lines.8 During the Senate hear

ings Mrs. Freeman testified for the Commission that legis

latures had done what they could to make black votes

“worth little” by drawing “lines of legislative districts

6 Id., p. 34-35.

7 Hearings before Subcommittee No. 5 of the House Committee

on the Judiciary on H.R. 4249, 91st Cong., 1st Sess., p. 17 (1969).

*Id., p. 3.

7

to divide concentrations of Negro voting strength.” 9 Other

witnesses testified to the use of this device as well as

related practices such as use of multi-member districts.10

During the House and Senate debates repeated concern

was expressed that the value of minority votes would be

diluted by submerging them in districts with white major

ities.11

The need to apply section 5 to reapportionment cases was

particularly great because, as the Civil Eights Commission

pointed out, constitutional attacks on these efforts to dilute

black votes had been largely unsuccessful.12 Although this

Court held open the possibility that multimember districts

might not be invulnerable to judicial scrutiny, this Court

rejected all such challenges prior to 1973. See Whitcomb

v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124 (1974); Kilgarlin v. Hill, 386 U.S.

120 (1967); Fortson v. Dorsey, 379 U.S. 433 (1965). A

silmilar device, the annexation of white suburbs to a city

with a large minority population, was upheld in Burnette

v. Davis, 382 U.S. 42 (1965), affirming Mann v. Davis, 245

F. Supp. 241 (E.D. Va. 1965). The possibility of a judicial

challenge to gerrymandering of district lines, first raised

in this Court in Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960),

was complicated if not dimmed by a later decision laying

great emphasis on proof of discriminatory motives. Wright

v. Rockefeller, 376 U.S. 52 (1964).

9 Hearings before the Subcommittee on Constitutional Eights of

the Senate Committee on the Judiciary on Bills to Amend the

Voting Eights Act, 91st Cong., 1st and 2d Sess., p. 47 (1969-70).

10 Id., pp. 195-96, 469 (Efforts to frustrate the Act include

“redistricting to nullify local black majorities.”)

11115 Cong. Eec. 38486 (Eemarks of Eep. McCulloch) ; 116 Cong.

Eec. 5520-21 (Eemarks of Senator Scott), 5527 (Remarks of Sen

ator Scott), 6168 (Remarks of Senator Scott), 6358 (Eemarks of

Senator Bayh) (1970).

12 Political Participation, p. 35, n.63.

8

The Commission noted with particular concern the judi

cial treatment of constitutional challenges to certain Mis

sissippi redistricting which the Commission believed was

adopted for the express purpose of diluting black votes and

evading the Voting Rights Act. The challenge to the gerry

mandering of congressional lines was summarily rejected

on the ground that the black plaintiffs had to prove dis

criminatory purpose, and could not do so merely by offer

ing newspaper reports of statements made by the relevant

legislators. Connor v. Johnson, 11 Race Rel. Rep. 1859,

1863 (S.D. Miss. 1966). A challenge to the gerrymandered

legislative districts was summarily rejected when the dis

trict court refused to even consider the racial composition

of the new districts. Connor v. Johnson, 265 F. Supp. 492,

498-99 (S.D. Miss. 1967), aff’d 386 U.S. 483 (1967). Al

though all of these districting changes had survived con

stitutional challenges, none had ever been submitted for ap

proval under section 5. The Commission called on the

Attorney General to take steps, especially with regard

to Mississippi, to enforce section 5 as it applied, inter alia,

to changes in election districts.13 During the 1969-70 hear

ings on renewal of the Voting Rights Act, the Attorney Gen

eral repeatedly testified that a ban on any discriminatory

“purpose or effect” was broader than the unelaborated

constitutional prohibition.14 The Assistant Attorney Gen

eral in charge of the Civil Rights Division told the Senate

Committee, “[T]he real innovation about section 5 . . .

was that it contained language that changes with discrimi-

13 Political Participation, p. 184. The failure of the Attorney

General to take steps to enforce section 5 in similar circumstances

was discussed in Perkins v. Matthews, 400 U.S. 379 (1971).

14 Hearing's before Subcommittee No. 5 of the House Committee

on the Judiciary on H.R. 4249, 91st Cong., 1st Sess., p. 280 (1969) ;

Hearings before the Subcommittee on Constitutional Rights of the

Senate Committee on the Judiciary on Bills to Amend the Voting

Rights Act, 91st Cong., 1st and 2d Sess., pp. 189-190 (1969-70).

9

natory effect were in violation of the law. Most of us used

to assume, and the courts, I think, pretty well held, that if

you were to attack a State law as being in violation of the

15th Amendment, you would need to prove that there was

a discriminatory legislative purpose.” 15 Thus the Commis

sion concluded that the application of section 5 was neces

sary to stop redistricting practices which could not be

dealt with effectively through ordinary litigation.

In the years immediately preceding and following the

enactment of the Voting Eights Act, the principle tactics

used to prevent black participation in the political process

were direct obstacles to registration and voting. More

recently, however, the fashioning of district lines and multi

member districts to dilute the effectiveness of minority

votes have become the “prime weapons” of those seeking to

frustrate the purposes of the Act. Perkins v. Matthews,

400 U.S. 379 (1971). In January, 1975, the Civil Eights

Commission reported that

The most serious problem for minority voters now is

practices which dilute the minority vote. The greatest

use of section 5 has been in preventing such practices.16

Between 1971 and 1974 the Attorney General interposed

objections to 51 different redistricting plans in six states

involving congressional, legislative, county supervisors,

police jury, school board, parish council, and city council

districts.17 In objecting to these plans under Section 5 the

15 Hearings before the Subcommittee on Constitutional Rights of

the Senate Committee on the Judiciary on Bills to Amend the

Voting Rights Act, 91st Cong., 1st and 2d Sess., p. 507 (1969-70).

18 The Voting Rights Act: Ten Years After, p. 345.

17 Id., pp. 400-409; David H. Hunter, Federal Review of Voting

Charges: How to Use Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, pp. 90-97

(1974).

10

Attorney General used the same standard applied in the

instant case—that district lines must not he drawn in such

a way as to divide up a concentration of minority voters

and submerge the fragments of that concentration in dis

tricts with larger numbers of white voters.18

This construction of Section 5, fashioned by the Attorney

General in a series of cases to assure that districting plans

would not have a discriminatory effect, should be accorded

the deference due “to the interpretation given the statute

by the officers or agency charged with its administration.”

Perkins v. Matthews, 400 U.S. 379, 391 (1971). Such defer

ence is particularly appropriate in the instant case, since

Congress is at this very moment considering a ten year

extension of the Voting Eights Act so as to apply the estab-

18 United States Commission on Civil Rights, the Voting Rights

Act: Ten Years After, pp. 204-327 (1975).

In opposing the district lines which were the subject of United

States v. Georgia, 411 U.S. 526 (1973), the Attorney General noted

that eight Georgia counties “form a contiguous group—of 89,626

persons, of whom 57.2 percent are nonwhite—enough to form at

least three new majority-nonwhite single-member districts. Yet the

submitted plan has only one district in the area with a slight non

white population majority (50.56 percent)—new District 59. The

other new districts (60, 63, 64, 76 and 78) are ‘border districts’

partly inside and partly outside the majority-nonwhite area and

have significant, but minority, nonwhite population percentages.

These demographic facts . . . do not permit us to conclude, as we

must under the Voting Rights Act, that this plan does not have a

discriminatory racial effect on voting”. Appendix, No. 72-75, pp.

11-12.

In 1971 the Attorney General opposed the lines defining the

supervisors’ districts in Yazoo County, Mississippi because “the

district boundary lines within the City of Yazoo unnecessarily

divide the black residential areas into each of the five districts.”

Letter of David Norman to Griffin Norquist, July 19, 1971, annexed

to Brief Amicus Curiae of the NAACP in United States v .Georgia,

No. 72-75, p. A-3. See also Letter of David Norman to Jack P. F.

Gremillion, August 20, 1971, pp. A-5 to A-10; Letter of David

Norman to Thomas Watkins, July 14, 1971, pp. A-13 to A-15.

11

lished standards to the redistricting that will follow the

1980 census.19

Plaintiffs suggest that the District Court was obligated

to uphold Plan II unless it affirmatively concluded that that

plan violated the Fourteenth or Fifteenth Amendment. But

Section 5 neither requires nor entails such a constitutional

inquiry. In adopting Section 5 Congress chose to establish

what it believed to be a clear and effective test by which

new election laws would be measured, in order to insure

that the right to vote was not denied or abridged on account

of race. Whether that test is characterized as merely man

dating an inference of unconstitutional gerrymandering

from a plaintiff’s failure to prove the absence of dis

criminatory purpose and effect, or as establishing a new

substantive rule forbidding district plans otherwise per

missible under the Constitution, Congress’ power to enact

Section 5 is beyond dispute. South Carolina v. Katzenbach,

383 U.S. 301 (1966); Katzenbach v. Morgan, 384 U.S. 641

(1966). Whatever may be the functional or substantive

relationship between the standards applied in section 5

case and in an ordinary challenge to the constitutionality of

a statute, it is the former which apply in the instant case.20

19 United States Commission on Civil Rights, The Voting Rights

Act: Ten Years After, p. 345 (1975); Hearings on H.R. 939 Be

fore a Subcommittee of the House Judiciary Committee, 94th

Cong., 1st Sess., p . ----- (1975) (Remarks of Rep. Rodino).

20 The resolution of this case does not require a delineation of

the precise differences and similarities between these standards.

Were this a constitutional challenge to the creation of a multi

member district, judicial inquiry might be appropriate into such

diverse and troublesome questions as whether blacks had sufficiently

distinct interests as to make separate representation important,

whether white councilmen had in the past been indifferent to those

interests and whether blacks would be better off as a majority of

a few districts or a substantial minority of a larger number of

districts. White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (1973). As to minority

voters in the states and subdivisions covered by Section 5, Congress,

drawing on its unique expertise and experience, has resolved these

12

Appellants ask this Court to overturn the established

construction of Section 5, claiming that it requires “maxi

mization” of black voting strength21 and urging that the

District Court was obligated to approve any districting

plan with a “rational basis”.22 The District Court opinion,

like section 5, does not require the creation of the maximum

feasible number of majority black districts;23 they merely

forbid the systematic dismemberment of black concentra

tions. Doubtless adherence to this statutory standard will,

in the instant case, result in at least two districts with

substantial majorities of black voters,24 but such a conse

quence is neither undesirable nor unforseen. Insofar as re

districting is concerned, Congress enacted section 5, not to

improve the geometric aesthetics of districting maps, but

because Congress knew—as did the draftsmen of Plan II—

that the consolidation or division of a concentration of black

voters would directly effect whether blacks from a majority

of one or more districts and whether black candidates can

be elected.25

questions in favor of creating districts in which black majorities

can elect black candidates. Although circumstances will at times

require the courts to determine such difficult political and socio

logical questions, a congressional resolution is certainly to be wel

comed. Compare Wright v. Rockefeller, 376 U.S. 52, 57-58 (1964),

with Taylor v. McKeithen, 499 F.2d 893 (5th Cir. 1974).

21 Brief for Appellants, p. 31.

22 Brief for Appellants, pp. 19-26.

23 Since blacks are now 38.2% of the voters in New Orleans, it

would probably be possible to draw district lines such that 3 out

of 5, or 4 out of 7, districts would have black majorities.

24 See Appendix, p. 626.

26 Consolidation will also affect the number of votes “diluted.”

Under Plan II, even treating District B as predominantly black,

there are 62,612 black voters in overwhelmingly white districts,

compared to only 18,694 white voters in a single marginal black

district. Appendix, p. 524. Under the Republican proposal there

would be 34,376 black voters in predominantly white districts and

28,384 white voters in predominantly black districts. Appendix,

p. 626.

13

Nothing in Section 5 or its legislative history would

require, or even permit, the Attorney General or a district

court to approve a voting change merely because it had

a “rational” or even “compelling” basis. The statute con

tains no express or tacit suggestion that the discriminatory

purpose or effect of a proposed change can be overcome

by a showing of some additional basis or effect of the

change, rational, compelling, or otherwise. Nor does the

statute distinguish between reapportionment and other

voting changes. Few* alterations in election laws and pro

cedure, particularly in the area of reapportionment,26 are

so bizarre that some rational basis for them cannot be

conjured up by a competent attorney; to require approval

of a discriminatory change because there was such a

rational basis would render section 5 a dead letter.27 See

Wright v. Council of City of Emporia, 407 U.S. 451, 462,

467-68 (1972). Once it found that Plan II had the pro

scribed discriminatory effect, the District Court’s inquiry

properly came to an end.

In light of the purpose and legislative history of section

5, plaintiffs were required to establish either that there

was no concentration of black voters in New Orleans or

that any such concentration or concentrations had not been

divided among predominantly white districts.

26 The various considerations bearing on reapportionment are so

diverse, and often inconsistent, as to afford a “basis” for virtually

any plan: compactness, continuity, respecting natural and man

made banners (which usually run in all directions), creating hetero

geneous district to avoid legislators favoring special interests (or

creating homogenous districts to achieve the opposite effect), divid

ing up black communities so they can influence several legislators

(or consolidating those communities so they have more control

over a smaller number of officials), avoiding “inadequate”' repre

sentation for a particular group (the choice of group controlling

the districting pattern), etc.

27 This Court rejected a similar contention in City of Petersburg,

Virginia V. United States, 4l0 U.S. 562 (1973); Jurisdictional

Statement in No. 74-865, p. 12.

14

2. T he Effect of P lan II

The District Court correctly concluded that the plaintiffs

had failed to establish that Plan II would not dilute the

votes of black voters. The court found that black voters

were concentrated in a east-west belt running through New

Orleans, that that concentration was divided among five dif

ferent districts and combined with large numbers of white

voters, and that bloc voting by whites rendered unlikely

if not impossible the election of black candidates from at

least four of the districts. These findings of fact were sup

ported by the record, and plaintiffs do not challenge their

correctness on appeal.

Racial discrimination in voting was for years prior to

the Voting Rights Act a serious problem in Louisiana.28

When Reconstruction ended in Louisiana there were sub

stantially more blacks registered to vote than whites, but

by 1910 blacks accounted for less than the 1% of the state

registration.29 The principle device for limiting the fran

chise to whites was a literacy test adopted in 1898 for the

express purpose of discriminating against blacks.30 After

the Second World War black registration began to rise, a

pattern accelerated by this Court’s decision in Brown v.

Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954). In the late 1950’s

a program of concerted activities was undertaken by the

Louisiana Legislature, the State Board of Registration, the

State Attorney General and the Association of Citizens

Councils of Louisiana to prevent further minority registra

tion and to remove blacks from the existing rolls.31 A series

28 See generally Hearings in Louisiana Before the U.S. Commis

sion on Civil Rights (48).

29 1961 United States Commission on Civil Rights Report: Vot

ing, pp. 40-41.

30 See Official Journal of the Constitutional Convention of the

State of Louisiana 1898, passim.

311961 United States Commission on Civil Rights Report: Vot

ing, 48-48.

15

of civil actions prosecuted by the United States failed to

bring an end to this active discrimination. See e.g. United

States v. McElveen, 177 F. Supp. 355, 180 F. Supp. 10, 11

(E.D. La. 1960), aff’d sub nom., United States v. Thomas,

362 U.S. 58 (1960); United States v. Association of Citizens

Councils of Louisiana, 187 F. Supp. 846 (W.D. La. 1960);

United States v. Louisiana, 380 U.S. 145, 148-49 (1965).

The passage of the Voting Eights Act brought a dramatic

change in black registration. In 1964 only 28.4% of eligible

blacks were registered in New Orleans, accounting for

barely 17% of the registered voters.82 During the following

three years over 24,000 blacks registered to vote, raising

black registration to 25.1% of the total.33 By May 1973

34.5% of the registered voters were black.34 In the year

between May 1972 and May 1973 minority registration rose

by 2,512, while white registration actually declined by

4,895.86 As of October, 1974, 38.2% of those voters were

black.36 New Orleans thus presents precisely the situation

in which Congress feared district lines would be drawn so

as to divide concentrations of black voters and thus dilute

the value of their vote.

The District Court correctly determined that the black

community wTas concentrated in the manner with which

Congress was concerned.

Although some black families are to be found in

most of the principal areas of New Orleans, there is no

32 1961 United States Commission on Civil Rights Report: Vot

ing, p. 267.

33 Political Participation, A Report of the United States Com

mission on Civil Rights (1968), p. 241.

34 Appendix, p. 623.

35 Compare id. 622 with id. 623.

36 United States Commission on Civil Rights, The Voting Rights

Act: Ten Years After, p. 368.

16

general geographical blending of black and white resi

dences. The black population is heavily concentrated

in a series of neighborhoods extending eastwardly and

westwardly through the central part of the City; the

areas lying north and south of this belt, with minor

exceptions, are overwhelmingly white.87

Plaintiffs do not question the correctness of this finding,

which is fully supported by the record. The vast majority

of black voters live in a belt approximately a mile wide

running the length of the city from east to west; one can

traverse the city from St. Jefferson Parish eight miles to

St. Bernard Parish without crossing more than one or two

white precincts.38 This black concentration is separated

from the predominantly white parts of New Orleans by a

variety of man made barriers, including interstate high

ways,39 limited access highways,40 divided multi-lane main

37 Jurisdictional Statement, p. 4a.

38 See Appendix, p. 620. This map, based on 1971 figures sub

stantially understates the. size of the minority vote, Blacks consti

tuted approximately 31% of the registered voters in 1971, compared

to 38.2% of the voters in October, 1974.

39 Interstate 10 separates the black Desire section (Ward 9,

precincts 28, 28-A, 28-B, 28-C) from, the white neighborhood to

the north (Ward 9, precincts 29, 29-A, 30, 30-A, 31, 31-A), and

the black portions of the central city (Ward 2, precincts 6, 6-A, 7;

Ward 17, precincts 14 and 16) from the white neighborhood to the

north (Ward 3, precincts 12, 15, 16, 18, 19, 20) ; Interstate 610

separates the black community east of Dillard University (Ward

7, precincts 27, 27-A, 27-B) from the white neighborhood north of

the Fairgrounds Race Track (Ward 7, precincts 18 and 19).

40 The Pontchartrain Parkway, U.S. 9, separates the black central

city (Ward 2, precincts 1, 2, 3, 4) from the downtown business

area (Ward 3, precinct 1).

17

thoroughfares,41 cemeteries,42 the Inner Harbor Canal43 and

City Park.44 There are virtually no black voters in certain

white parts of the city, including the northern third of the

city45 and the neighborhoods surrounding Loyola and Tu-

lane Universities.46

The effect of Plan. II, as Plan I before it, was to system

atically dismember this concentration of black votes and to

place fragments in each of 5 separate districts with larger

41 St. Claude Avenue separates the black areas to the north

(Ward 9, precincts 2, 3, 3-A, 3-B, 4, 5, 5-A, 6, 6-A, 6-B, 8, 22, 23,

24, 25, 25-A, 26, 27) from the white river front (Ward 9, precincts

1, 1-A, 7, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16); Florida Avenue separates those

same black areas from the white community north of the Avenue

and east of the Intercoastal Waterway (Ward 9, precinct 32),

and falls between the black southern portions of Wards 7 and 8

(Ward 7, precinct 8; 9, 9-A, 20, 20-A, 21; Ward 8, precincts 11

and 12) and the white portions of those wards to the north ; St.

Charles Avenue separates the black central city (Ward 1, precincts

5, 6, 7; Ward 10, precincts 10-H; Ward 11, precincts 10-19; Ward

12, precincts 11, 12, 13) from the white riverfront area to the

south (Ward 1, precincts 1-4; Ward 10, precincts 1-9; Ward 11,

precincts 1-9, Ward 12, precincts 1-8.)

42 The Metairie and Greenwood Cemeteries separate the black

neighborhood to the south (Ward 17, precincts 13, 13-A, 14, 15,

16) from the white neighborhoods to the north (Ward 17, pre

cincts 18-21).

43 The Canal separates the black Desire section (Ward 9, pre

cincts 28, 28-A, 28-B, 28-C) from the white area to the east (Ward

9, precinct 32) and separates the black development at Pontchar-

train Park (Ward 9, precincts 31-B, 31-C, 31-D and 31-E) from

the white area to the east (Ward 9, precincts 33, 42, 42.)

44 The Park separates the black community near Dillard Uni

versity (Ward 7, precincts 27-A, 27-B, 26-A, 27, 28, 28-A) from the

white portions of Ward 5 across the Park.

46 Excepting small black communities near Dillard University,

a predominantly black college, and near Pontchartrain Park, until

recent times the park used by blacks who were excluded because

of their race from City Park.

46 The Director of the City Council Staff which prepared Plan II

acknowledged the existence of these black and white concentrations.

Appendix, p. 238.

18

numbers of whites. The black neighborhood north west

of the French Quarter immediately adjoins even larger

black areas to the east and west; in District C, however,

that neighborhood is paired with the all-white neighbor

hoods of Lake Vista, 5 miles to the north across City Park,

and Aurora Gardens, 5 miles to the south across the Mis

sissippi River. The black voters in the southern portions

of wards 7 and 8 are combined, not with their black neigh

bors in Wards 6 and 9, but with the white residential area

on the shore of Lake Pontchartrain 3 miles to the north.

The black community concentrated between Florida and St.

Claude Avenues is divided betwen Districts D and E, each

of which has a larger number of white voters. The black

community along the Jefferson Parish line is separated

from the nearby central city neighborhoods, and combined

instead with white West End area miles to the north and

the Tulane area miles to the south.47 With one exception,

the districts are long and thin, crossing natural and man

made boundaries to pair fragments of black concentration

with larger but distant white areas; District C is a mile

wide and 12 miles long.

Had the district lines been drawn to reflect the natural

and man-made boundaries which separate the black con

centration from the rest of the city, or had the districts

merely been reasonably compact, two or more districts with

a substantial majority of black voters would have resulted.

The Republican plan, for example, resulted in two districts

with black majorities in excess of 60%.48 Instead, Plan II

carefully divided that black community among the five city

council districts, none receiving more than 21,000 or less

than 11,000 minority voters. Thus, the 83,588 black voters

concentrated in the center of New Orleans were divided so

47 See Appendix, p. 638.

48 Appendix, p. 626,

19

that—at the time Plan II was drawn up—every district

had a white majority. After the preparation of Plan II,

and before the decision below, a significant rise in black

registration raised the number of black voters in District

B to 52.6%.49 The next largest concentration of black voters

is in District E, which not coincidentally has the fastest

growing white population in the city.50 Given the obstacles

posed by the high concentration of black voters and the

geography of New Orleans, it would be difficult to design a

districting plan better suited to avoiding a substantial black

majority in any one district and thus preventing the election

of a black candidate.61

The District Court correctly concluded that the diluting

effect of Plan II was aggravated by a history of bloc voting

substantially along* racial lines.52 Three of the plaintiff

counoilmen conceded there was such bloc voting in New

Orleans,68 and two of defendants’ witnesses confirmed the

existence of this problem.64 Although a black candidate

49 Appendix, p. 624. Plan II was prepared in 1972 while Plan I

was still under consideration by the Attorney General. Id., pp.

350-51. Between May, 1972 and May, 1973, black registration rose

from 79,213 to 83,588, an increase of 5.5%. But for this increase

blacks would have constituted only 49.8% of District B.

60 Appendix, p. 187.

61 The effect of Plan I may have been slightly worse, but this

was accomplished by making 3 of the 5 districts non-eontinuous.

Appendix, p. 623.

Plaintiffs do not deny that it would he entirely feasible to fashion

a compact, districting plan that did not divide the black community

among white districts. Nor does such a claim appear to have

been raised in any of the other 50 cases in which the Attorney

General objected to a redistricting plan. The existence of a con

centration of black voters guarantees ipso facto that a non-dilutive

districting plan can be drawn which is compact, contiguous, and

consistent with Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964).

62 Jurisdictional Statement, pp. 18a-19a.

53 Appendix, pp. 260, 506-07, 545-46, 548.

64 Id., pp. 414, 547; see also Exhibits 29, 30, 33.

20

running against several whites in a primary might obtain

a plurality in a majority white district, state law requires

that the nominee obtain a majority and mandates a second

primary where necessary. La. Eev. Stat., Art. 18, § 358

(1966 Supp.). On several occasions blacks have won such

pluralities, only to lose the runoff election to a white

candidate due to white bloc voting.55 Although the Demo

cratic nomination is usually tantamount to election, on at

least one occasion a black Democratic candidate so nom

inated was defeated when white traditionally Democratic

wards voted in favor of a white Republican. Until

restrained from doing so by this Court, Louisiana in the

past encouraged such bloc voting by printing on the ballot

the race of each candidate. Anderson v. Martin, 375 U.S.

399 (1964).

Plaintiffs object that, in considering whether Plan II had

a discriminatory effect, the District Court was obligated

to ignore the fact that 2 of the 7 Council members were to

be chosen through an at-large election which, particularly

in view of the majority runoff and anti-single shot laws,

guaranteed the defeat of any black candidate.66 They also

suggest that, in assessing the impact of Plan II, the District

Court should have disregarded the “social, economic and

political context” in which it operated.57 The effect of a

proposed statute, however, cannot be assessed in the

abstract; it depends on the particular circumstances, legal

and otherwise, in which it is applied. The Assistant At

torney General advised Congress in 1970 that any judgment

on boundary changes would require demographic or other

55 Appendix, pp. 501, 564-6, 569; Jurisdictional Statement, pp.

19a, 64a; see also Anderson v. Martin, 375 U.S. 399, 401 (1964).

56 Brief for Appellants, pp. 10-12.

57 Brief for Appellants, p. 16.

21

information.58 A similar argument was rejected by this

Court in City of Petersburg v. United States, 410 U.S. 962

(1973)69 and United States v. Georgia, 411 U.S. 526 (1973).60

The Attorney General’s regulations regarding Section 5

submissions have long required the submission of extensive

information on the background and impact of any submis

sion, especially when redistricting is involved. 28 C.F.R.

§ 51.10. The District Court, by detailing the legal and

factual context which led it to reject Plan II, provided

guidance to the City Council in fashioning a method of

electing the Council which would be consistent with sec

tion 5.61

The Fifteenth Amendment does not require that every

racial minority must in all cases be represented by a pro

portionate number of couneilmen or legislators. But

neither does the Constitution afford any protection to a

districting plan well calculated to prevent minority repre-

68 Hearings before the Subcommittee on Constitutional Eights

of the Senate Committee on the Judiciary on Bills to Amend the

Voting Rights Act, 91st Cong., 1st and 2nd Sess., p. 507 (1969-70).

59 The City, which wished to annex a predominantly white suburb,

unsuccessfully urged that the District Court which disapproved

that annexation under seetion 5 had erred when it took into con

sideration the fact that the Petersburg City Council was chosen

at large. Jurisdictional Statement, No. 74-865, pp. 13 et seq.

60 Georgia urged that the Attorney General had erred when, in

assessing the effect of its reapportionment plan, he considered the

impact of the state’s multimember district and majority runoff laws.

See Brief for Appellants, No. 72-75, pp. 25-30. This Court held

that the Attorney General’s inquiry was so limited, “Seetion 5 is

not concerned with a simple inventory of voting procedures, but

rather with the realty of changed practices as thev affect Negro

voters.” 411 U.S. at 531.

61 In City of Petersburg, supra, the District Court advised the

plaintiffs that the annexation, though discriminatory under the

then existing circumstances, would pass muster under section 5 if

the at-large method of election were replaced by districts. 354

F.Supp. 1021, 1031 (D.D.C., 1972), a f d 410 U.S. 962 (1973).

22

sentation, or to insure no more than token representation

in a city where blacks are close to a majority of the popula

tion. In the instant case, although blacks constituted

45.0% of the population and 38.2% of the registered voters,

section 5 could not assure that ordinary “political defeat

at the polls” would not prevent the election of a substantial

number of blacks to the New Orleans City Council. Whit

comb v. Chavis, 403 IPS. 124, 153 (1971). Plan II, however,

as the District Court noted, did more than subject black

candidates to the everyday risks of the political process; it

harnessed the established pattern of white bloc voting to

create an insurmountable obstacle to the election of more

than a single black.

II.

Plaintiffs Failed to Prove That Plan II Did Not Have

the Purpose of Denying or Abridging the Right to

Vote on Account of Race.

Section 5 requires plaintiffs to establish not only that

Plan II would not have a discriminatory effect, but also

that it did not have a discriminatory purpose. In the in

stant case the District Court did not reach the latter issue,

since it ruled for defendants on the former.62 It is clear,

however, that plaintiffs failed to meet their burden of

proof with regard to the purpose of Plan II. This failure

affords an alternative ground for affirming the decision of

the District Court.

Plan II was not the first districting proposal submitted

by the City Council. On March 2, 1972 the Council adopted

Ordinance 4796, (hereinafter referred to as “Plan I”),

providing for the redistricting of the New Orleans City

62 Jurisdictional Statement, pp. 40a-42a.

23

Council. On January 15, 1973, the Attorney General ob

jected to Plan I. In Ms letter of that date, the Assistant

Attorney General spelled out the basis for the objection

so as to make clear what steps were needed to fashion a

non-discriminatory plan:

Our analysis shows that the district boundary lines

in the submitted plan are drawn in a manner which ap

pears to dilute black voting strength by combining a

number of black voters with a larger number of white

voters in each of the five districts.68

Plaintiffs do not question the correctness of the Attorney

General’s decision regarding Plan I. Four months after

the rejection of Plan I the City Council, on May 13, 1973,

adopted Plan II. The controlling question is whether, as

plaintiffs claim, Plan II represented a good faith attempt

to remedy the defects in Plan I.

The most striking evidence in this regard is that Plan II

did not alter in any significant way the defects in Plan I,

The boundaries of Districts D and E were identical in

both plans.64 The total number of black voters in District B

rose from 20,012 to 20,976, an increase of 964, but much of

this change was attributable to the increase in minority

registration between 1972 and 1973.66 White registration

in District B fell, but this too was due in large measure to

a decline in white registration in City as a whole. The

only significant effect of Plan II, outside of the Algiers

area, was to move District B to the northeast, adding to it

several thousand black voters in Wards 2 and 3 and re

moving from it an almost equal number in Ward 13. This

63 Appendix, p. 29.

64 Compare Appendix, p. 27 with p. 31,

65 Appendix, pp. 623-624. The total number of registered blacks

in Districts A, B and C rose from 44,253 on May 4, 1972 to 45,546

on May 9,1973, an increase of 1,023.

24

worked a net transfer of approximately 1,000 black voters

from District C to District A, a change of no practical sig

nificance since both districts remained at least 75% white.

In Plan II blacks continued to be divided among the five

districts, and in virtually the same proportions as before.66

The dilution worked by Plan I was carried forward virtu

ally unchanged by Plan II.

The reason why Plan II failed to remedy the defects

noted by the Attorney General is also clear from the

record. The member of the Council staff who prepared

Plan II conceded that plan had been drawn up before

Plan I was rejected,67 and the Director of the Council

staff testified that in. preparing Plan II it was the staff’s

desire to leave “undisturbed the general racial composi

tion of the districts”.68 The bill containing Plan II recites

that it was introduced by one of the councilmen on De

cember 7, 1972, a month prior to the Attorney General’s

decision. Plan II was drawn up by the Council staff, not

as a result of the Attorney General’s decision, but because

of complaints from the residents of the predominantly

white Algiers section, who objected to being divided among

three different council districts and paired in part with

District A, whose residents had a conflicting attitude re

garding proposals for a neve bridge across the Missis-

66 The proportion of New Orleans’ black voters in each of the

districts under Plans I and II was as follows:

Plan I Plan II

District A 14.59% 15.50%

District B 25.26% 25.09%

District C 16.01% 13.88%

District D 21.24% 21.89%

District B 22.89% 23.71%

67 Appendix, pp. 3,50-51, 354.

68 Id., p. 213.

25

sippi.69 The changes worked by Plan II on the borders of

Districts A, B and C were “a result of” the decision to

consolidate the fragments of Algiers and place them in

District C,70 not of any desire to remedy the defects of

Plan I.

The reasons why the Council put forward Plan II, which

it must have known to be inadequate, rather than attempt

ing to draw up a new non-discriminatory plan, are not hard

to devine. The councilmen who voted for Plan II had more

than a casual interest in preventing the election of blacks,

for any such election would cost one of the incumbents his

seat. The potential for abuse inherent in this situation was

compounded by the fact that each councilman drew the lines

of his own district in consultation with the incumbent in

the neighboring district.71 Although at-large Council

man Moreau, the ostensible author of both plans, insisted

he took no interest in the racial composition of the dis

tricts,72 the councilmen wdiose districts were at stake asked

for and were given racial breakdowns on the various options

before the plans were finally drafted.73

Over and above the danger of defeat by a black candidate,

there was another reason why the Council was unwilling to

take the steps necessary to remedy the defects in Plan I.

With a single exception, all the members of the Council

lived in the white lake-front area in the north end of the

city.74 Any meaningful solution to the failings of Plan I

would have required the council districts to run from east

69 Id , pp. 112, 197.

70 Id., p. 223.

71 Id., p. 339.

72 Id., pp. 269-279.

73 Id , pp. 144-45, 208, 339.

74 Id , pp. 125, 232, 235.

26

to west rather than north to south, which would have placed

several incumbent councilmen in the same lake-front dis

trict. Despite some equivocation by plaintiffs’ witnesses, it

was clear that the Council had no intention of considering a

plan that placed incumbents in the same district, and that

th Council staff so understood.76

Nor is there any suggestion in the record that the Coun

cil or its staff did not understand that federal law forbade

fragmentation of the black community so as to dilute

minority voting strength. The record is replete with

evidence that they fully comprehended what was required

of them.76 The lame excuses offered for their failure to

do so are unpersuasive.77 The conclusion is inescapable

that the members of the City Council failed to remedy the

defects in Plan I, not through inadvertance, nor through

blind adherence to any lofty neutral principles, but be

cause they were unwilling to give up the practical political

benefits conferred on them by continued dilution of black

voting strength.

76 Id., pp. 120-21, 146, 148-50, 152, 192, 214, 229, 230, 232, 235,

297, 337, 344, 547, 571, 575, 580.

76 Id., pp. 176, 195, 206, 245, 263, 265, 333, 352, 541.

77 One witness said the north-south districts were fashioned to

conform to the natural boundaries of the city, but virtually all the

boundaries he listed served not as the boundaries of the districts

but as internal barriers. Id. p. 185-87. Several witnesses insisted

it would be impossible to draw east-west districts without dis

rupting existing precincts, id. pp. 187, 200, 326, 514, but in view

of the fact there were over 400 precincts it was conceded that the

only east-west plan proposed had not had this effect. Id. pp.

199, 575.

27

CONCLUSION

For the above reasons the judgment of the District

Court should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack G reenberg

J am es M. N a brit , III

C h a rles E. W il l ia m s , III

E ric S c h n a p p e r

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

S ta n ley A. H a l p in , J r .

Suite 1212

344 Camp Street

New Orleans, Louisiana 70103

C h a rles E. C otton

D avid D e n n is

301 Executive House

New Orleans, Louisiana 70112

W il e y B ranton

666 Eleventh Ave., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20001

Counsel for Appellees Jackson, et al.

ME11EN PRESS IN C — N. Y. C. 219

IN THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR

THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 9 9 -2 3 8 9 , 9 9 -2 3 9 1 , 0 0 -1 0 9 8 and 0 0 -1 4 3 2

TERRY BELK, e t ah,

P lain tiffs-A p p ellan ts,

and

WILLIAM CAPACCHIONE, MICHAEL P. GRANT, e t ah,

P la in tiff-In terven ors-A p p ellees,

v.

THE CHARLOTTE-MECKLENBURG BOARD OF EDUCATION, e t ah,

D efen d an ts-A p p ellan ts.

WILLIAM CAPACCHIONE, MICHAEL GRANT, e t ah,

P la in tiff-In terven ors-A p p ellees,

and

TERRY BELK, e t ah,

P la in tiffs-A ppellan ts,

v.

THE CHARLOTTE-MECKLENBURG BOARD OF EDUCATION, e t ah,

D efen dants-A ppellants.

A ppeal From th e U n ited S ta te s D istr ic t Court

for th e W estern D istr ic t o f N orth C arolina

REPLY BRIEF IN FINAL FORM OF APPELLANTS

CHARLOTTE-MECKLENBURG BOARD OF EDUCATION, ET AL.

Allen R. Snyder

Maree Sneed

Jo h n W. Borkowski

HOGAN & HARTSON L.L.P.

555 T hirteenth Street, N.W.

W ashington, DC 20004

(202) 637-5741

Dated: May 19, 2000

Jam es G. Middlebrooks

Irving M. B renner

Amy Rickner Langdon

SMITH HELMS MULLISS

& MOORE, L.L.P.

201 N. Try on S treet

Charlotte, NC 28202

(704) 343-2051

Leslie W inner

G eneral Counsel

C harlotte-M ecklenburg

Board

of Education

Post Office Box 30035

C harlotte, NC 28230-0035

(704) 343-6275

C ounsel for A ppellants

C harlotte - M ecklenburg

Board of Education, et al.

MEILEN PRESS INC. —- N. Y. C. «̂ ggis*> 219