Supreme Court Rejects Legal Defende Permission to File as Amicus Curiae in Employer Case

Press Release

April 13, 1953

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Loose Pages. Supreme Court Rejects Legal Defende Permission to File as Amicus Curiae in Employer Case, 1953. 9819b2b9-bb92-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/dfb9e030-ea74-4085-8a01-a043b852a273/supreme-court-rejects-legal-defende-permission-to-file-as-amicus-curiae-in-employer-case. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

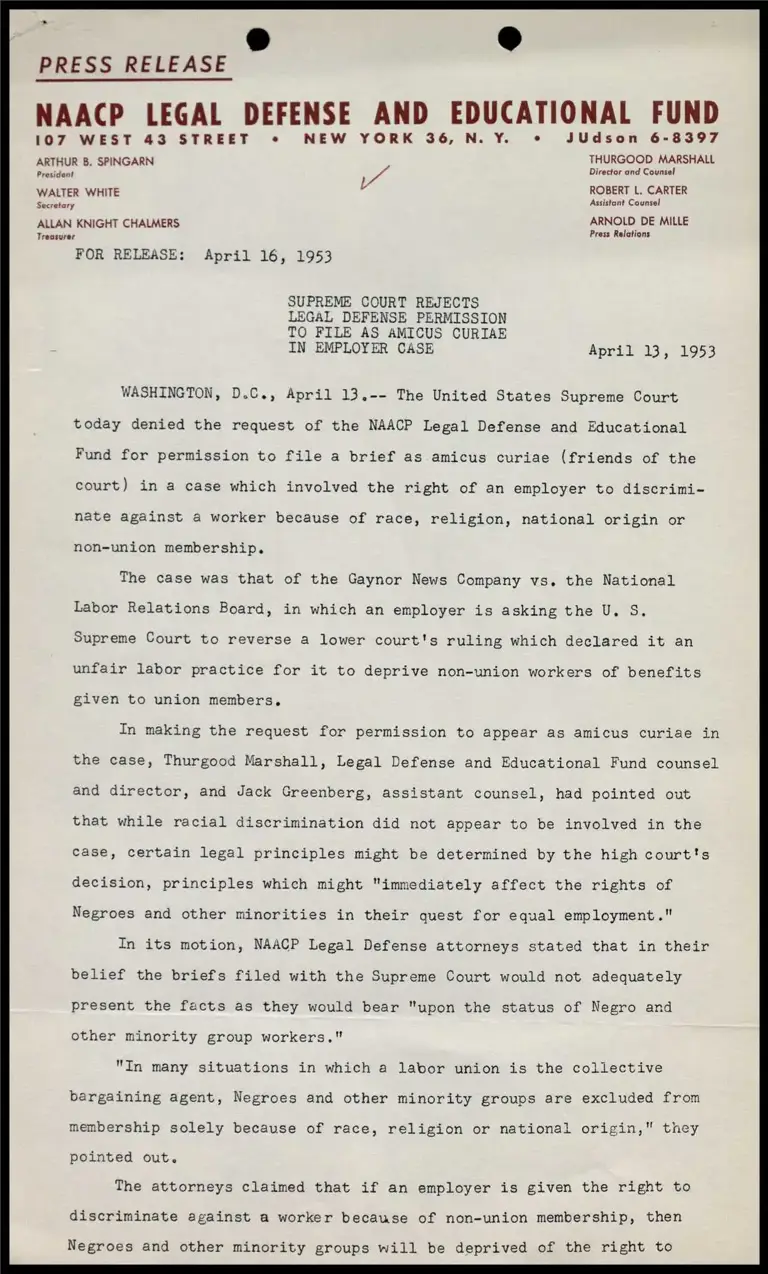

PRESS RELEASE

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND

107 WEST 43 STREET * NEW YORK 36, N. Y. © JUdson 6-8397

THURGOOD MARSHALL

ells oxo L eae Director and Counsel

ROBERT L, CARTER WALTER WHITE howe cons

ALLAN KNIGHT CHALMERS ARNOLD DE MILLE

Treasurer Press Relations

FOR RELEASE: April 16, 1953

SUPREME COURT REJECTS

LEGAL DEFENSE PERMISSION

TO FILE AS AMICUS CURIAE

IN EMPLOYER CASE April 13, 1953

WASHINGTON, D.C., April 13.-- The United States Supreme Court

today denied the request of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational

Fund for permission to file a brief as amicus curiae (friends of the

court) in a case which involved the right of an employer to discrimi-

nate against a worker because of race, religion, national origin or

non-union membership.

The case was that of the Gaynor News Company vs. the National

Labor Relations Board, in which an employer is asking the U. S.

Supreme Court to reverse a lower court's ruling which declared it an

unfair labor practice for it to deprive non-union workers of benefits

given to union members,

In making the request for permission to appear as amicus curiae in

the case, Thurgood Marshall, Legal Defense and Educational Fund counsel

and director, and Jack Greenberg, assistant counsel, had pointed out

that while racial discrimination did not appear to be involved in the

case, certain legal principles might be determined by the high court's

decision, principles which might "immediately affect the rights of

Negroes and other minorities in their quest for equal employment."

In its motion, NAACP Legal Defense attorneys stated that in their

belief the briefs filed with the Supreme Court would not adequately

present the facts as they would bear "upon the status of Negro and

other minority group workers."

"In many situations in which a labor union is the collective

bargaining agent, Negroes and other minority groups are excluded from

membership solely because of race, religion or national origin," they

pointed out.

The attorneys claimed that if an employer is given the right to

discriminate against a worker because of non-union membership, then

Negroes and other minority groups will be deprived of the right to

+ legal Defense and Educational Fund Press ee 16 Page 2

file unfair labor practice charges with the National Labor Relations

Board and will therefore be deprived of equal employment opportunity.

The Gaynor News Company had first refused the Legal Defense Fund

permission to file in connection with the case. Refusal by the Supreme

Court means that NAACP attorneys will not be able to participate in the

case in any capacity.

RESTRICTIVE COVENANT APPEAL

BEFORE SUPREME COURT April 16, 1953

WASHINGTON, D.C., April 16,-- The question as to whether a person

has the right to go into court and to sue and recover money damages from

another who failed to live up to a race restrictive covenant or "con-

tract" will be argued before the United States Supreme Court Tuesday,

April 28,

Attorney for the National Association for the Advancement of Color-

ed People, Loren Miller of Los Angeles, who has successfully argued

several other restrictive covenant cases, will argue that a court's

awarding of damages for breach of restrictive covenant clauses or con-

tracts deprives a person of his constitutional rights and is in complete

violation of the l4th Amendment of the Constitution of the United States.

The case, entitled Barrow, et al, vs. Jackson, involves Mrs. Leona

Jackson, a white resident of a Southern California community, who in

1950 sold a house to persons she allegedly knew would let Negroes occupy

it. In the deed Mrs, Jackson refused to include a racial restrictive

clause, which would restrict the occupancy of the house to "Caucasians"

only. The parties who had signed the restrictive "contract" with Mrs,

Jackson sued her for damages in the California Superior Court. The case

was dismissed and on appeal both the California District Court of Appeal

and the California Supreme Court upheld the earlier decision.

In the brief filed with the United States Supreme Court, Mr. Miller

has called upon the high court to settle this question as to whether one

has the right to recover damages against a person who sells his property

to a member of another racial group in violation of a covenant. He

pointed out that California, Michigan and Washington, D.C. have ruled

that a person cannot do so, while Oklahoma and Missouri have upheld the

right of their courts to entertain damage actions of this kind.

"The Fourteenth Amendment does not proscribe individual action,"

says Mr, Miller in quoting the California court, "but when, as here, the

aid of a court is sought to compel one of the parties to the restrictive

covenant to abide by its terms by subjecting him to an action for

~ Legal Defense and Educational Fund Press ge eo 16 Page 3

damages because of the use or occupancy of the property by non-

Causians--it is no longer a matter of individual action: it is one of

State participation in the maintenance of racial residential segre-

gation."

Attorney Miller will be assisted by Thurgood Marshall, NAACP

Legal Defense and Educational Fund counsel and director, and Franklin

H, Williams, West Coast regional director.

FLORIDA SUPREME COURT

HEARS 2ND IRVIN APPEAL April 14,1953

TALLAHASSEE, Fla., April 14.-- Arguments in the appeal of the

second conviction of Walter Lee Irvin, sole surviving defendant in the

famous Groveland case, were heard today by the Florida Supreme Court.

Presenting the argument for Irvin, twice convicted for the raping of a

white farmwife, were NAACP attorneys Thurgood Marshall, the Associa-

tion's special counsel of New York City, Jack Greenberg, also of New

York, Alex Akerman and Paul Perkins, both of Orlando, Fla.

Hearing on the appeal was twice postponed because of a hip injury

suffered by Attorney Akerman. It was first scheduled for January 27,

but when Mr. Akerman slipped and fell while getting off the plane on

his way to the courthouse, it was put off until February 17. The

second postponement was requested because the NAACP lawyer had not

recovered sufficiently to keep the date.

Irvin was first sentenced to death in 1949 when he, Samuel

Shepherd and Charles Greenlee were convicted for reaping the Groveland

farmwife. Shepherd was also given a death sentence. Greenlee, then

16, was sent to prison for life. He did not appeal and is now in the

state penitentiary. A fourth Negro, Ernest Thomas, was shot to death

by a sheriff's posse before he ever reached a courtroom.

The conviction and death sentence of Irvin and Shepherd were

taken to the United States Supreme Court by the NAACP. In April,

1951, the high court ordered a new trial, Justice Robert H. Jackson,

in his concurring opinion, stated that the events surrounding the

first trial did not "meet any civilized conception of due process of

law."

On the eve of the new trial, in November, 1951, Irvin and

Shepherd were shot down in the middle of the night on a lonely road

by the sheriff while he was transporting the two men from the state

penitentiary to the site of the new trial, Shepherd was killed and

6. Legal Defense and a ey Fund Press rede wer 16 Page 4

Irvin seriously injured.

The second trial was held in Ocala early in 1952, After one

hour and twenty-three minutes deliberation, the all-white jury brought

back a "guilty" verdict and Walter Lee Irvin was again sentenced to

death by Judge T. J. Futch.

In their argument before the Florida Supreme Court, the NAACP

attorneys cited twenty-two errors committed by the lower court in

convicting and sentencing Irvin. Most glaring were the refusal of the

trial court to admit into evidence a public opinion poll showing

prejudice against Irvin in the county of the trial, the refusal of the

trial court to order a mistrial after the State's Attorney had made

prejudicial remarks to the jury, and the introduction into evidence of

articles seized without a search warrant.

A decision is not expected to be handed down for at least several

weeks.

=30=