Brief on Behalf of Defendants-Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1972

191 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Brief on Behalf of Defendants-Appellants, 1972. ba1738a6-53e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e03c60c1-7b56-4db2-8dc9-98db25a5fd49/brief-on-behalf-of-defendants-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

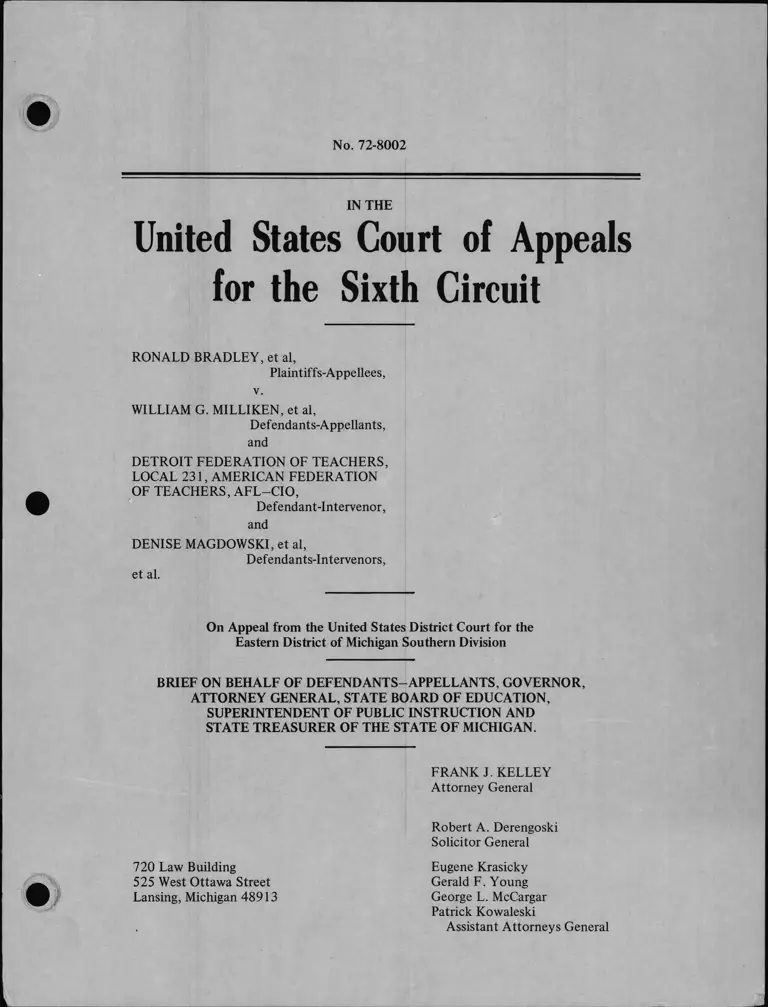

No. 72-8002

IN THE

United States Court of Appeals

for the Sixth Circuit

RONALD BRADLEY, et al,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

v.

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al,

Defendants-Appellants,

and

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS,

LOCAL 231, AMERICAN FEDERATION

OF TEACHERS, AFL-CIO,

Defendant-Intervenor,

and

DENISE MAGDOWSKI, et al,

et al.

Defendants-Intervenors,

On Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Michigan Southern Division

BRIEF ON BEHALF OF DEFENDANTS-APPELLANTS, GOVERNOR,

ATTORNEY GENERAL, STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION,

SUPERINTENDENT OF PUBLIC INSTRUCTION AND

STATE TREASURER OF THE STATE OF MICHIGAN.

FRANK J. KELLEY

Attorney General

720 Law Building

525 West Ottawa Street

Lansing, Michigan 48913

Robert A. Derengoski

Solicitor General

Eugene Krasicky

Gerald F. Young

George L. McCargar

Patrick Kowaleski

Assistant Attorneys General

No. 72-8002

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

RONALD BRADLEY, et al,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

v.

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al,

Defendants-Appellants,

and

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS,

LOCAL 231, AMERICAN FEDERATION

OF TEACHERS, AFL-CIO,

Defendant-Intervenor,

and

DENISE MAGDOWSKI, et al,

et al.

Defendants-Intervenors,

- ____________________________________________________________________/

On Appeal from the United States District

Court for the Eastern District of Michigan

Southern Division

BRIEF ON BEHALF OF DEFENDANTS-APPELLANTS, GOVERNOR,

ATTORNEY GENERAL, STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION, SUPER

INTENDENT OF PUBLIC INSTRUCTION AND STATE TREASURER

OF THE STATE OF MICHIGAN.

720 Law Building

525 West Ottawa Street

Lansing, Michigan 48913

FRANK J. KELLEY

Attorney General

Robert A. Derengoski

Solicitor General

Eugene Krasicky

Gerald F. Young

George L. McCargar

Patrick Kowaleski

Assistant Attorneys General

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Table of Cases ------------------------------------

Statement of Questions Involved---------- --------

Statement of Case ---------------------------------

Argument

I. Under Michigan law, local school districts

are created by the legislature as local

state agencies and bodies corporate

governed by locally elected boards of

education having such powers as are

conferred by statute -----------------------

II. Based on the record in this case, the

District Court's findings of fact and

conclusions of law of de jure segregation

in the public schools of the Detroit

School District is erroneous ---------------

III. The lower court erred in admitting into

evidence and relying upon evidence of

alleged racial discrimination in housing

by persons not parties to this cause, in

finding de jure segregation in the

Detroit Public Schools -------------------------

IV. The lower court's legal conclusion of de jure

segregation by these defendants in the matter

site selection for school construction is

erroneous as a matter of law -------------------

V ' Iwi,?'OWer-court erred in denying these defendants'

41(b) motions to dismiss made at the close of

plaintiffs' case in chief ----------------------

VI. The lower court erred in making findings

against tnese defendants based on evidence

introduced after these defendants had made

their 41(b) motions and elected to stand on

such motions at the close of plaintiffs'

case in c h i e f ---------------------- ------------

iv

xiii

2

9

34

40

47

51

65

'

VII.

VIII.

IX.

X.

XI.

The lower court's legal conclusion of

systematic educational inequality between

Detroit and the surrounding mostly white

suburban school districts, based upon

transportation funds, bonding limitations,

and the state school aid formula, is

erroneous as a matter of l a w ------------- ■— 6 8

Based on the record in this cause, the

Detroit public schools are not de jure

segregated schools as a result of the

conduct of any of the state defendants

h e r e i n----------- ---- -— --- ------------------ gg

A finding of de jure segregation as to some

schools within the Detroit school district

does not warrant a desegregation remedy for

all schools in the school district. Only

those schools within the school district

found to be de jure segregated schools

must be desegregated------------------------ 97

Based on the record in this case, a

constitutionally adequate unitary school

system can be established within the

geographical limits of the Detroit school

district-------------------------------------- 3_02

Where only the Detroit school district has

been found to have committed acts of de jure

segregation, and in the absence of any claims,

proofs or findings concerning either the

establishment of the boundaries of the 86

public school districts in Wayne, Oakland and

Macomb counties or whether any of these 86

school districts, except Detroit, have

committed any acts of de jure segregation, the

District Court may not adopt a metropolitan

remedy including at least 53 school districts

and 780,000 pupils------------------ --------- 113

XII. State officials may not be compelled by a

District Court in a school desegregation

remedial order to perform acts beyond

their lawful authority to perform under

state l a w ------------ ----------------------

XIII. The expenditures of state funds from the

state treasury required by the District

Court in this case are not authorized by

the appropriation acts of the Michigan

legislature as required by the Michigan

Constitution-------------- ------------------- 134

XIV. Section 803 of the education amendments of

1972, Pub. L. No. 92-318, applies to

metropolitan transportation orders which

have been or may be entered by the District

Court in this c a s e -------------------------- 149

XV. Section 80 3 is constitutional---------------- igg

Addendum------------------------------------------- 270

Conclusion-------------------- ^71

INDEX OF AUTHORITIES

Page

A & N Club v Great American Insurance Co,

404 F2d 100, 103-104 (CA 6 , 19 6 8 )------------ 51, 52,

65, 6 6 , 78, 95*

Airport Community Schools v State Board of

Education, 17 Mich 574 (1969) ---------------- 30

Alexander v Holmes County Board of Education,

396 US 19, 20 --------------------------------- 105

Attorney General, ex rel. Zacharias v Board of

Education of City of Detroit, 154 Mich 584 (1908) 19

Bacon v Kent-Ottawa Metropolitan Water Authority,

354 Mich 159 (1958) --------------------------- H

Baker v Carr, 369 US 186, pp 194-195 Footnote 15,

(1962 -------- ----- ----------------------------- 59

Beech Grove Investment Company v Civil Rights

Commission, 380 Mich 405 (1968) -------------- 4 3 , 44

Board of Education v City of Detroit,

30 Mich 505 (1875) ---------------------------- 1 4 , 32

Board of Education of Presque Isle Township

School District No. 8, Presque Isle County

Board of Education, 357 Mich 148 (1959) ----- 13, 20

Board of Education of the City of Detroit v

Superintendent of Public Instruction, 319

Mich 436 (19 47) ------------------------------- 9

Bradley, et al v Milliken, et al, 433 F2d

897 (1970) ------------------------------------ 21

Bradley, et al v School Board of the City of

Richmond, Virginia, et al, 51 FRD 139, 142

Bradley v School Board of City of Richmond

Virginia (CA 4, No 72-1058, February 8, 1972)

Bradley, et al v School Board of the City of

Richmond,___F 2 d _____ (CA 4, decided ~

June 5, 1972) ---- --------- ------------------ 104, 120

Brown v Board of Education, 347 US 483 (1954)- 34

Burruss v Wilkerson, 310 F Supp 572, 574

(WD Va 1969) affirmed 397 US 44 (1970)------ 80, 83,

Child Welfare Society of Flint v Kennedy

School District, 220 Mich 290 (1922) ------- 19

Common Council of the City of Detroit v

Engel, 202 Mich 536 (1918) ----------------— 19

Corpus Christi Independent School District v 169

Cisneros, 404 US 1211 (1971) ----------------

Cotton v Scotland Neck City Board of Education,

92 S Ct 2214 (1972) -------------------------- H O

Dandrige v Williams, 397 US 471, 485 (1970) — 74

Davis v School District of City of Pontiac, Inc,

443 F2d 573, 575 (CA 6, 1971), cert den

404 US 913 (1971) ----------- -----------------

Deal v Cincinnati Board of Education, 369 F2d

55, 60-61 (CA 6, 1966) cert den 389 US

847 (1967) -----------------------------------

Deal v Cincinnati Board of Education, 419 F2d

1387, 1392 (CA 6, 1969), cert den 402 US

962 (1971) --------- --------------------------

Duplex Printing Press Co v Derring,

254 US 443 (1921) ----------------------------

Edgar v United States, 404 US 1206 (1971) ----

Fox v Employment Security Commission, 379 Mich

579, 588 (1967) -------------------------------

Gentry v Howard, 288 F Supp 495, 498

(ED Tenn, 1969)

40, 46,

40,

40, 41,

162

124

58

121, 129

36

84, 95

50, 128, 169

128

128

v

Green v School Board of New Kent County,

391 US 430 (1968) -------- — ------- ------ 110, ISO, 168

Griffin v County School Board of Prince

Edward County, 377 US 218, 228 (1964) ---- 53, 133

Iliers v Detroit Superintendent of Schools,

376 Mich 225 (1965) ---------- -------------- 16, 31, 47, 91

Hobson v Hansen, 269 F Supp 401, 495

(D.D.C. 1967) modified sub.nom. ---------- 90, 92

Imlay Township Primary School District No. 5

v State Board of Education, 359 Mich 478

(I960) --------- --------------________----- 20

In re School District No. 6 , Paris and

Wyoming Townships, Kent County, 284 Mich

132 (1938) — ------------------------------- 19

In re State of New York, 256 US 490, 497 (1921) 53

Ira School District No. 1 Fractional v

Chesterfield School District No. 2

Fractional, 340 Mich 678 (1954) ---------- 19

Jipping v Lansing Board of Education, 15

Mich App 441 (1968), Leave to Appeal denied

382 Mich 760 (1969) ----------------------- 1 7 , 35

Jones v Grand Ledge Public Schools, 349 Mich 1,

(1957) ------------------------------------- 20, 32, 89,

90, 122

Kent County Board of Education v Kent County

Tax Allocation Board, 350 Mich 327 (1957)— 11

Keyes v School District No. 1, Denver Colorado,

313 F Supp 61, 74-75 (D Colo, 1970),

modified 445 F2d 990, 1006, (CA 10, 1971),

cert granted 804 US 1036 (1972) ---------- 90, 92, 98, 99,

1 0 0 , 128

Gordon v Lance, 403 US 1 ( 1 9 7 1 ) ------------ - 77

vi

Lockerty v Phillips, 319 US 182, 187 (1942) ----

MacQueen v City Commission of City of

Port Huron, 194 Mich 328 (1916) ---------------

Marathon School District No. 4 v Gage, 39 Mich

484 (1878) — --------------------- 1-------------

Margeta v Ambassador Steel Co, 380 Mich 513 (1968)

Mason v Board of Education of the School District

of the City of Flint, 6 Mich App 364 (1967) — -

Mclnnis v Ogilvie, 394 US 322 (1969) ------------

Mclnnis v Shapiro, 293 F Supp 327, 335-336

(ND 111 1968) -----------------------------------

King v Smith, 392 US 309 (1968) -----------------

McKibbin v Corporation and Securities Commission,

369 Mich 69 (1963) ------------------------------

Michigan Education Association, et al v

State Board of Education, Michigan Court of

Appeals, No. 11,900 -----------------------------

Milliken v Kelley, et al v Allison Green, et al,

Supreme Court, No. 53,809 ------------------------

Munro v Elk Rapids Schools, 383 Mich 661 (1970) -

Northcross v Board of Education of Memphis,

Tenn, 420 F2d 546, 548 (1969) ------- ----------

Penn Scnool District No. 7 v Lewis Cass Inter

mediate School District Board of Education,

14 Mich App 109, 120 (1968) --------------------

People, ex rel. Tibbals v Board of Education of

of Port Huron, 39 Mich 635 ---------------------

Plessy v Ferguson, 163 US 537 (1896)-------------

vii

84

Ranjel v City of Lansing, 417 F2d 321, 324 (CA 6 ,

1969), cert den 397 US 980 (1970), reh den

397 US 1059 (1970) -----------------------------

Rehberg v Board of Education of Melvindale,

Ecorse Township School District No. 11, Wayne

County, 330 Mich 541, 548 (1951) — ------------

School District for the City of Holland v

Holland Education Association, 380 Mich 314

(1968)------------------------------ -----------

School District Number Three of the Township of

Everett v School District Number One of the

Township of Wilxox, et al, 63 Mich 51 (1886) —

School District of the City of Lansing v State

Board of Education, 367 Mich 591 (1962) -------

Schwan v Lansing Board of Education, 27 Mich

App 391 (1970) ----------------------------------

Sengnas v L'Anse Creuse Public Schools, 368

Mich 557 (1962) ---------------------------------

Smith v North Carolina State Board of Education,

444 F2d 6 (CA 4, 1971) --- ----------------------

Smith, et al v State Board of Education, Ingham

County Circuit Court, No. 12167C ---------------

Smuck v Hobson, 408 F2d 175 (DC Circuit, 1969) —

Sparrow v Gill, 304 F Supp 8 6, (MD NC 1969) -----

Spencer v Kugler, 326 F Supp 1235, 1242-1243

(DC NJ, 1971) , affirmed on appeal 404 US

1027 (1972) -------------------------------------

Sturgis v County of Allegan, 343 Mich 209 (1955)-

State Board of Agriculture v Auditor General

226 Mich 417, 425 (1924) -----------------------

26

27, 31

13

11, 12, 20

26, 32

15

131, 132

79

90, 92

74

36, 41, 46, 50,

103, 104, 105,

119, 129

20

142

V l l l

Swann v Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 US 1, 15-18 ( 1971) — ----------------------- 35, 37, 40

50, 99, 100, 106, 117, 120, 128, 129

151

Taylor v Board of Education of City School

District of City of New Rochelle, 191 F Supp

181 (SD, NY, 1961), appeal dismissed 288 F2d

600 (CA 2, 1961), 195 F Supp 231 (SD, NY, 1961)

affirmed 294 F2d 36 (CA 2, 1961), cert den 368

US 940 (1961) ----------------------------------- 98

The People, ex rel Workman v Board of Education

of Detroit, 18 Mich 399, 408-409 (1869) ------- 34

Township of Saginaw v School District No. 1 of the

City of Saginaw, 9 Mich 540 (1862) --------------- 14

United States v Board of Education (CA 10, 1922) ,

459 F2d 720 -------------------------------------

United States v School District 151 of Cook County,

Illinois, 301 F Supp 201 (ND 111, 1969), affirmed

as modified 432 F2d 1147 (CA 7, 1970) cert den

402 US 943 (1971) ---------------------------------- 132

United States v State of Texas, 321 F Supp 1043

(ED Tex, 1970), 330 F Supp 235 (ED Tex, 1971),

affirmed and modified 447 F2d 441 (CA 5, 1971) 123, 124

United States of America v Texas Education

Agency, ___ F2d _____ (CA 5, August 2, 1972) - 100

Van Fleet v Oltman, 244 Mich 241 (1928)---------- 19

Weinberg v Regent of University, 97 Mich 246,

254 (1893) ---------- ---------------------------- 142

Welling v Livonia Board of Education, 382 Mich

620, 623 (1969) --------------------------------- 9, 22, 23,

24, 25, 26, 28, 31

Williams v Primary School District #3,

Green Township, 3 Mich App 468 (1966) --------- 12

xx

Wright v Council of City of Emporia US

92 S Ct 2196 (1972), 40 US LW 4806 US June 20,

1972 ------------ ------------------------------ 33, 38,

122, 123

Wright v Rockefeller, 376 US 52 (1964) -------- 55

109,

x

Michigan Constitution

1835, art 1 0 , § 3

1850, art 13, § 4

1908, art 5, §; 13

1908, art 1 0 , § 2 1

1908, art 1 0 , § 23

1908, art 1 1 , § 2

1908, art 1 1 , § 6 •

1908, art 1 1 , § 9 •

1963, art 1 , § 2 -

1963, art 5, § 19 -

1963, art 5, § 29 -

1963, art CO > 073 2 —

1963, art 073CO 3 —

1963, art 9, § 6 —

1963, art 9, § 1 1 -

1963, art 9, § 17 -

Michigan Public Acts

1937 PA 120 ------

1962 PA 175 ------

1969 PA 306 ------

1969 PA 307 ------

9

136

11

9

20 ,22

20

9, 20

58, 59

54, 144

43

9

■ 9, 2 1 , 34, 58, 59, 70

•2 1 , 2 2 , 23, 24, 31, 48

60, 93, 142

71, 122

31, 145

131

135, 136, 137, 138, 139

49

31, 43, 48, 49

143

xx

1970 PA 48, § 12 94

1970 PA 84 -------------------------------------- 143

1970 PA 100 ------------------------------------- 72,

77,

1971 PA 1 2 0 ----------------------------------- - 143

1972 PA 225 -------------- ---------------------- 137,

1972 PA 246 ----------- — ---------------------- - 140,

1972 PA 258 -------- ---------------------------- 29,

147,

MCLA 16.400-402; MSA 3.29(300)-29(302) ------- 25

MCLA 24.201 et seq; MSA 3.560(101) et seq ---- 23

MCLA 3 40.1 et seq; MSA 15.3001 et s e q -------- 9,

15, 16, 18, 25,

30, 34, 76, 133

MCLA 388.621; MSA 15.1919(61) ------- ---------- 72,

MCLA 564.101 et seq; MSA 26.1300(101) et seq -

73, 74,

85

138, 140

143, 144, 148

144, 145,

148

146

1 1 , 14,

26, 28,

77

FR Civ P 41(b) ------------------------------------- 51, 65

Journal of the House No. 98, p 2705 ------- ------ 137

Journal of the Senate No. 96, p 1 8 1 4 ------------ 137

Michigan Manual, 1971-1972, pp 366-408 ---------- 73

Opinions of the Attorney General

1928-30, pp 498, 502 ---------- ---------------- 14

1960, Vol 2, p 138-139 — --------------------- 89

1960, Vol 2, p 140-142 ------------------------ 89

1963-64, p 1 4 2 ------------- ----------- -------- 44

1969-70, p 1 5 6 ------------------- --------------- 27

1971, May 5, No. 4707------------ ---- --------- 27

xii

STATEMENT OF QUESTIONS INVOLVED

II.

III.

IV.

WHAT IS THE PRECISE LEGAL STATUS UNDER STATE

LAW OF LOCAL SCHOOL DISTRICTS AND BOARDS OF

EDUCATION VIS-A-VIS THE STATE OF MICHIGAN?

The lower court did not answer this question.

These defendants say that under Michigan law,

local school districts are created by the

legislature as independent local state agencies

and bodies corporate governed by locally elected

boards of education having such powers as are

conferred by statute.

WHETHER, BASED ON THE RECORD IN THIS CASE, THE

DISTRICT COURT'S FINDINGS OF FACT AND CONCLUSIONS

OF LAW OF DE JURE SEGREGATION IN THE PUBLIC

SCHOOLS OF THE DETROIT SCHOOL DISTRICT IS ERRONEOUS?

The lower court answered "no."

These defendants say the answer is "yes."

WHETHER THE LOWER COURT ERRED IN ADMITTING INTO

EVIDENCE AND RELYING UPON EVIDENCE OF ALLEGED

RACIAL DISCRIMINATION IN HOUSING BY PERSONS NOT

PARTIES TO THIS CAUSE, IN FINDING DE JURE

SEGREGATION IN THE DETROIT PUBLIC SCHOOLS?

The lower court answered "no."

These defendants say the answer is "yes."

WHETHER THE LOWER COURT'S LEGAL CONCLUSION OF

DE JURE SEGREGATION BY THESE DEFENDANTS IN THE

MATTER OF SITE SELECTION FOR SCHOOL CONSTRUCTION

IS ERRONEOUS AS A MATTER OF LAW?

The lower court answered "no."

These defendants say the answer is "yes."

Xiii

V. WHETHER THE LOWER COURT ERRED IN DENYING THESE

DEFENDANTS' 41(b) MOTIONS TO DISMISS MADE AT

THE CLOSE OF PLAINTIFFS' CASE IN CHIEF?

The lower court answered "no."

These defendants say the answer is "yes."

VI. WHETHER THE LOWER COURT ERRED IN MAKING FINDINGS

AGAINST THESE DEFENDANTS BASED ON EVIDENCE

INTRODUCED AFTER THESE DEFENDANTS HAD MADE

THEIR 41(b) MOTIONS AND ELECTED TO REST AND

STAND ON SUCH MOTIONS AT THE CLOSE OF PLAINTIFFS'

CASE IN CHIEF?

The lower court answered "no."

These defendants say the answer is "yes."

VII. WIETHER THE LOWER COURT'S LEGAL CONCLUSION

OF SYSTEMATIC EDUCATIONAL INEQUALITY BETWEEN

DETROIT AND THE SURROUNDING MOSTLY WHITE

SUBURBAN SCHOOL DISTRICTS, BASED UPON TRANS

PORTATION FUNDS, BONDING LIMITATIONS, AND THE

STATE SCHOOL AID FORMULA, IS ERRONEOUS AS A

MATTER OF LAW?

The lower court answered "no."

These defendants say the answer is "yes."

VIII. WHETHER, BASED ON THE RECORD IN THIS CAUSE,

THE LOWER COURT ERRED IN RULING THAT THE

DETROIT PUBLIC SCHOOLS ARE DE JURE SEGREGATED

SCHOOLS AS A RESULT OF THE CONDUCT OF ANY OF

THESE DEFENDANTS HEREIN?

The lower court answered "no."

These defendants say the answer is "yes."

xiv

IX.

X.

XI.

WHETHER THE LOWER COURT ERRED IN RULING,

BY IMPLICATION, THAT A FINDING OF DE JURE

SEGREGATION AS TO SOME SCHOOLS WITHIN THE

DETROIT SCHOOL DISTRICT WARRANTS A DESEGRE

GATION REMEDY FOR ALL SCHOOLS IN THE SCHOOL

DISTRICT?

The lewer court, by implication, answered "no.

These defendants say the answer is "yes."

WHETHER, BASED ON THE RECORD IN THIS CASE,

A CONSTITUTIONALLY ADEQUATE UNITARY SYSTEM

OF SCHOOLS CAN BE ESTABLISHED WITHIN THE

GEOGRAPHICAL LIMITS OF THE DETROIT SCHOOL

DISTRICT?

The lower court answered "no."

These defendants say the answer is "yes.

WHETHER THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN RULING

THAT, WHERE ONLY THE DETROIT SCHOOL DISTRICT

HAS BEEN FOUND TO HAVE COMMITTED ACTS OF

DE JURE SEGREGATION, AND IN THE ABSENCE OF

ANY CLAIMS, PROOFS OR FINDINGS CONCERNING

EITHER THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE BOUNDARIES

OF THE 86 PUBLIC SCHOOL DISTRICTS IN WAYNE,

OAKLAND AND MACOMB COUNTIES, OR WHETHER ANY

OF THESE 86 SCHOOL DISTRICTS, EXCEPT DETROIT,

HAVE COMMITTED ANY ACTS OF DE JURE SEGREGATION,

IT MAY ADOPT A METROPOLITAN REMEDY INCLUDING

AT LEAST 53 SCHOOL DISTRICTS AND 780,000 PUPILS?

The lower court answered "no."

These defendants say the answer is "yes."

xv

XII.

XIII .

XIV.

XV.

WHETHER THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN RULING

THAT THESE DEFENDANT STATE OFFICIALS MAY BE

COMPELLED BY A DISTRICT COURT IN A SCHOOL

DESEGREGATION REMEDIAL ORDER TO PERFORM

ACTS BEYOND THEIR LAWFUL AUTHORITY TO

PERFORM UNDER STATE LAW?

The lower court answered "no."

These defendants say the answer is "yes."

WHETHER THE LOWER COURT ERRED IN REQUIRING

THESE DEFENDANTS TO MAKE EXPENDITURES FROM

THE STATE TREASURY THAT ARE NOT AUTHORIZED

BY THE APPROPRIATION ACTS OF THE MICHIGAN

LEGISLATURE AS REQUIRED BY THE MICHIGAN

CONSTITUTION?

The lower court answered "no."

These defendants say the answer is "yes."

WHETHER SECTION 803 OF THE EDUCATION

AMENDMENTS OF 1972, PUB. L. No. 92-318,

APPLIES TO METROPOLITAN TRANSPORTATION

ORDERS WHICH HAVE BEEN OR MAY BE ENTERED

BY THE DISTRICT COURT IN THIS CASE?

The lower court did not answer this question

These defendants say the answer is "yes."

WHETHER SECTION 803 OF THE EDUCATION

AMENDMENTS OF 1972, PUB. L. No. 92-318,

AS APPLIED TO METROPOLITAN TRANSPORTATION

ORDERS IN THIS CAUSE, IS CONSTITUTIONAL?

The lower court did not answer this question

These defendants say the answer is "yes."

xvi

No. 72-8002

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

RONALD BRADLEY, et al,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

v.

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al,

Defendants-Appellants,

and

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS,

LOCAL 231, AMERICAN FEDERATION

OF TEACHERS, AFL-CIO,

Defendant -Intervenor,

and

DENISE MAGDOWSKI, et al,

Defendants-Intervenors

et al.

/

On Appeal from the United States District

Court for the Eastern District of Michigan

Southern Division

BRIEF ON BEHALF OF DEFENDANTS-APPELLANTS

GOVERNOR, ATTORNEY GENERAL, STATE BOARD

OF EDUCATION, SUPERINTENDENT OF PUBLIC

INSTRUCTION AND STATE TREASURER OF THE

STATE OF MICHIGAN

STATEMENT OF CASE

(References to the record herein are references to the pages

of the Appendix unless otherwise indicated by TR for trans

cript and EX for exhibits.)

Plaintiffs filed their class action complaint on

August 18, 1970, alleging (a) the constitutional invalidity

of Sec. 12 of 1970 PA 48 ( iaio ) and (b) that the

policies and practices of the defendants have the purpose and

effect of perpetuating a racially segregated system of public

schools in which both pupils and school personnel are assigned

to particular schools on the basis of race. (Ial7)

Plaintiffs' complaint sought declaratory relief and temporary

and permanent injunctive relief limited to remedying alleged

racial segregation in the Detroit public schools by the establish

ment of a system of unitary public schools therein. (Ial9~21)

The plaintiffs in this cause are parents and their

children attending schools in the Detroit School District

which has a 63„8%black student body. The defendants included

tlie Detroit Board of Education, three of its members and its

Superintendent, the Governor, Attorney General, State Board

of Education and Superintendent of Public Instruction of the

State of Michigan. The Detroit Board of Education, a body

corporate, has been represented throughout this cause by

private counsel of its own choosing.

-2-

On October 13, 1970, this Court held Section 12

of 1970 PA 48 unconstitutional, affirmed the lower court's

denial of a preliminary injunction to, inter alia, implement

the Detroit Board of Education's April 7 plan, which would

have altered the attendance zones of twelve high schools

to effect a more balanced ratio of Negro and white students

at those 12 schools over a 3 year period, and reversed the

lower court's order dismissing the Governor and Attorney

General as parties "at least at the present stage of the

proceedings." 433 F2d 897, 905.

On December 3, 1970, in response to plaintiffs'

motion for immediate implementation of the April 7 plan and

the Detroit Board of Education's alternate McDonald and

Campbell plans, the lower court entered an order directing

trie implementation of the McDonald Plan in September, 1971.

The McDonald Plan involved providing specialized curriculums

at certain high schools that would serve two of the eight

regions within the school system with the expectation of

attracting students from a wider area, on a voluntary basis,

thereby achieving a greater degree of integration. This plan,

which was implemented in September, 1971, also provided for

establishing certain middle or junior high schools having

racially balanced enrollments. (Ial04-112 ) This Court,

on appeal, denied plaintiffs' motion for summary reversal of

-3-

such order and directed the District Court to set the case

for hearing forthwith. 438 F2d 945.

Prior to the trial on the merits, the District Court

permitted the intervention, as defendants, of the Detroit

Federation of Teachers, the collective bargaining organi

zation representing all teachers within the Detroit school

system, and Magdowski, et al, a group of parents with children

attending the Detroit public schools.

The trial on the merits concerning the allegations

of de jure segregation in the Detroit public schools commenced

on April 6 , 1971. On September 27, 1971, the lower court

issued its "Ruling on Issue of Segregation" holding:

" . . . [T]hat both the State of Michigan and

the Detroit Board of Education have committed

acts which have been causal factors in the

segregated condition of the public schools

of the City of Detroit. . (Ia21Q)

These defendants respectfully submit that such

holding is erroneous. The Detroit Board of Education, found

innocent by the trial court of any racial discrimination as

to faculty and staff, has not, on the basis of the trial

record, conducted the operation of the school district with

the purpose and effect of segregating children by race in the

public schools under its jurisdiction. As to these defendants,

-4-

it will be demonstrated that the lower court's adverse

ruling is not supported by either the facts or the applicable

law in this matter. These defendants, in the course of their

conduct as elected or appointed public officials, have not,

based on the record in the cause, committed any acts with

the purpose and effect of segregating children by race in

the Detroit public schools.

On November 5, 1971, the District Court entered its

order directing the defendants to prepare and submit both

intra-district and metropolitan plans of desegregation .

(Ia220-221)

The school districts of Allen Park, et al,

Grosse Pointe, Royal Oak and Southfield, each a body corporate

under Michigan law and represented by private counsel of its

own choice, were allowed to intervene, as defendants. In

addition, Green, et al, Tri-County Citizens for Intervention

in Federal School Action No. 35257, was permitted to intervene

as a defendant. These interventions were pursuant to the

lower court's order of March 15, 1972. (Ia407-410)

The lower court entered various rulings and orders

in the process of shaping a metropolitan remedy involving

Detroit and 52 other school districts having approximately

780,000 students or 1/3 of the public school pupils in the

-5-

state of Michigan. ( Ia539 ) . Eighteen of the

affected school districts, each a body corporate, with

the power to sue and be sued under Michigan law and the

authority to retain private counsel of its own choosing,

have never been parties to tnis litigation. Further, the

lower court directed these defendants to pay for the

acquisition of at least 295 buses, at an approximate cost

of 3 million dollars, to implement an interim or partial

metropolitan remedy in September, 1972, and added the State

Treasurer as a party defendant for purposes of affording

such relief. ( ia576-579)

A metropolitan remedy was decreed by the lower

court in the absence of any proofs or findings concerning

either the establishment of the boundaries of the 53 affected

school districts or whether, with the exception of Detroit,

any of the other 52 school districts has committed any acts

of de jure segregation, ( ia497-498 ) Further, although

the lower court had expressly found no de jure segregation

as to faculty and staff in the Detroit public schools

( Ia2Q5-209 ) r each school within the judicially created

metropolitan desegregation area must have at least 1 0%

black faculty. (Ia540-541)

-6-

On July 20, 1972, the lower court entered an order

directing that each of the following enumerated orders:

"1. Ruling on Issue of Segregation,

September 27, 1971;

"2. Ruling on Propriety of Considering a

Metropolitan Remedy to Accomplish

Desegregation of the Public Schools

of the City of Detroit,

March 24, 1972;

"3. Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law

on Detroit-Only Plans of Desegregation,

March 28, 1972;

"4. Ruling on Desegregation Area and

Development of Plan, and Findings of

Fact and Conclusions of Law in Support

thereof, June 14, 1972; and

"5. Order for Acquisition of Transportation,

July 11, 1972

"shall be deemed final orders under Rule 54(b)

of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure and

the court certifies the issues presented therein

under the provisions of 28 U.S.C. 1292(b)."

(Ia59Q-591)

On the same date, this Court entered its order

granting both the motion of these defendants under 28 USC

1292(b) for leave to appeal from the five orders set forth

above and the motion of these defendants for a stay of

proceedings, other than planning proceedings, pending

appeal ( Ia592-593 ) . On August 1, 1972, these

defendants also filed a Notice of Appeal from these same

five orders.

-7-

In the interests of facilitating a clear

presentation and conserving space by avoiding repetition,

the remaining facts relevant to each question presented

for review will be set forth in connection with the argument

on each question.

-8-

ARGUMENT

I.

UNDER MICHIGAN LAW, LOCAL SCHOOL DISTRICTS

ARE CREATED BY THE LEGISLATURE AS LOCAL

STATE AGENCIES AND BODIES CORPORATE GOVERNED

BY LOCALLY ELECTED BOARDS OF EDUCATION HAVING

SUCH POWERS AS ARE CONFERRED BY STATUTE

A. The legal nature of Michigan School Districts

In Michigan, as authorized by the Michigan Con

stitution of 1963, art 8, § 2, the legislature has provided

for the organization of school districts, pursuant to the

provisions of 1955 PA 269, MCLA 340.1 et seq; MSA 15.3001

sometimes

et seq, hereinafter/referred to as the school code of 1955.

Welling v Livonia Board of Education, 382 Mich 620, 623 (1969).

Previous constitutional authority is found in Const 1908,

art 11, § 9 •, Const 1850, art 13, § 4 and Const 1835, art 10,

§ 3.

The meaning of the term "school district" came before

the Michigan Supreme Court for decision in Board of Education

of the City of Detroit v Superintendent of Public Instruction,

319 Mich 436 (1947). The people had adopted the term "school

district" in Const 1908, art 10, § 23, setting up a constitutional

fund for the support of school districts and other governmental

units. Thereafter the legislature passed an act designating

the state as one school district and making appropriation from

such fund to such single, state-wide school district. The

-9-

court rejected the formation of a single, state-wide school

district empowered only to receive appropriation.

". . . I n Board of Metropolitan Police of

the City of Detroit v. Board of Auditors of

Wayne Countyj 68 Mich. 576, 5*79, it was said:

"'Our State Constitution has provided for

local municipalities, embracing counties,

cities, villages, townships, and school

districts, which it has been held mean such

bodies of those names as were of a nature

familiar and understood.'

"The school district is commonly regarded as

a State agency. Attorney General, ex rel.

Kies, v. Lowrey, 131 Mich. 639; Attorney General,

ex rel. McRae, v. Thompson, 168 Mich. 511. Such

concept is scarcely consistent with the idea of

the State making itself a school district and

treating such district as an agency of the State

for the purpose involved in the instant case.

Webster's New International Dictionary (2d Ed.),

defines the term 'district' as:

"'A division of territory; a defined portion of

a state, county, country, town, or city, etc.,

made for administrative, electoral, or other

purposes; as, a Congressional, federal, judicial,

land, militia, magisterial, or school district.'

"Other dictionaries contain similar definitions,

thereby indicating the common understanding of

the word. It is, generally speaking, something

less than the whole. We think it may fairly be

said that the term 'school district' is commonly

regarded as a legal division of territory, created

by the State for educational purposes, to which the

State has granted such powers as are deemed

necessary to permit the district to function as a

State agency. Stuart v. School District No. 1 of

the Village of Kalamazoo, 30 Mich. 69"; Daniels v.

Board of Education of "the City of Grand.Rapids’,

191 Mich. 339 (L.R.A. 1916 F, 468); MacQueen v

City Commission of Port Huron, 194 Mich. 328;

Public Schools.of the city of Battle Creek v.

Kennedy, 245 Mich. 585.

-10-

"It should be noted also that under Act No. 331

the State school district is not vested with

powers and duties of the character commonly

delegated to school districts. It is declared

a school district for one purpose only, namely,

as indicated in the title of the act, 'to

receive, administer and disburse' certain

appropriations. Under chapter 3, §61, specific

authority with reference thereto is vested in

existing boards and commissions. In other words,

the State school district as such exercises no

prerogatives. . . . " pp 449-450 [Emphasis supplied]

School districts have also been held to be municipal

corporations. Marathon School District No. 4 v Gage, 39 Mich

484 (1878). In Kent County Board of Education v Kent County

Tax Allocation Board, 350 Mich 327 (1957), the Michigan

Supreme Court expressly held that school districts are "municipal

corporations" for the purpose of the tax limitation contained

in Const 1908, art 10, § 21. For the purpose of property tax

imposition, school districts possess the authority of "municipal

corporations." Bacon v Kent-Ottawa Metropolitan Water Authority,

354 Mich 159 (1958) .

More recently the Michigan Supreme Court in School

District of the City of Lansing v State Board of Education, 367

Mich 591 (1962), held that school districts are local state

agencies organized with plenary powers to carry out the delegated

functions given by the legislature.

The Michigan Court of Appeals has sought to harmonize

-11-

this apparent inconsistency by recognizing that for purposes

of tort liability school districts are considered state

agencies but they remain "municipal corporations" for

"purposes of property tax imposition." Williams v Primary'

School District #3, Green Township, 3 Mich App 468 (1966).

Thus, it is clear that for some purposes school

districts are agencies of the state and for other purposes

tney are municipal corporations. Under either designation,

it is abundantly clear that school districts are organized

by the legislature with plenary powers to carry out the

delegated functions given them by the legislature. School

District of tne City of Lansing v State Board of Education,

supra.

More importantly, the legislature has defined the

legal status of a school district in § 352 of the school

code, supra:

"Every school district shall be a body corporate

under the name provided in this act, and may sue

and be sued in its name. . . . "

In the case of first and second class school districts,

§ 192 and § 154 of the school code of 1955, supra, the legis

lature has designated the respective board of education to be

a body corporate with authority to "sue and be sued."

Tnus, Michigan school districts, by legislative

-12-

mandate, have been bodies corporate with power to sue and

be sued since at least 1881.

As a body corporate, a school district had the

right to invoke the aid of a court of equity to prevent an

illegal levy of taxes upon taxable property within the school

district. School District Number Three of the Township of

Everett v School District Number One of the Township of Wilcox,

et al, 63 Mich 51 (1886). It is noted that the litigant school

districts were neither represented by the Attorney General of

Michigan, Moses Taggart, nor by the Newaygo Prosecuting Attorney

but by private practitioners.

In fact the legal status of a school district

continues,even after the forced annexation of a closed school

district, to seek judicial aid or review so long as its pleadings

fairly present a justiciable controversy in some meritorious

respect. Board of Education of Presque Isle Township School

District No. 8 v Presque Isle County Board of Education, 357

Mich 148 (1953).

The legislature has also provided in § 609 of the

school code of 1955, supra:

-13-

"The board shall have authority to employ an

attorney to represent the school district or

board in all suits brought for or against the

district, and to render such other legal service

as may be for the welfare of the school district."

This express grant of power to hire its own attorneys to sue

or represent a school district or board of education when sued

was conferred by 1927 PA 319, Part II, Chap. 5, § 24, the

school code of 1927 supplanted by 1955 PA 269, the school

code of 1955, supra.

In OAG 1928-30, pp 498, 502, the Attorney General

ruled that the Prosecuting Attorney was not required to

represent school districts when sued because they were

empowered by law to employ their own attorneys.

The reported cases decided by the Michigan Supreme

Court since the time that Michigan became one of the states of

the United States list inumerable cases in which school districts

have been parties. A review of a broad sampling of these cases

reveals that the Attorney General of Michigan has not represented

school districts in such litigation. Rather, they have been

consistently represented by private attorneys selected by them.

See, for example: Township of Saginaw v School District No. 1

of the City of Saginaw, 9 Mich 540 (1862); Board of Education v

City of Detroit, 30 Mich 505 (1875); People, ex rel. Tibbals v

Board of Education of Port Huron, 39 Mich 635 (1878).

-14-

Generally, school districts are established by the

legislature pursuant to the appropriate provisions of the

school code of 1955, supra, as fourth class, third class,

second class and first class school districts, depending upon

school population census. Fourth class school districts are

provided for in §§ 51-77; third class school districts in

§§ 101-122; second class school districts in §§ 141-166; and

first class school districts in §§ 181-230 of the school code

of 1955, supra. Michigan also has primary school districts

(operating grades K-8 only) and special act school districts

established by the legislature, but since none of these classes

of school districts are within the metropolitan desegregation

area designated by the District Court, no further discussion

of such classes of school districts appears warranted.

Fourth class, third class, second class and first

class school districts are each governed by a board of education

elected by school electors of the respective districts. The

number of members of the board of education varies with the class

of the district.

Boards of education have such powers, express or by

reasonably necessary implication, as have been conferred by the

legislature. Senghas v L'Anse Creuse Public Schools, 368 Mich

557 (1962).

The powers of the various school districts are set forth

-15-

specifically in enumerated sections of the school code of 1 9 5 5 ,

supra, listed above as pertaining to the specific class school

district as well as generally in the appropriate provisions of

the school code of 1 9 5 5 , supra.

It must be stressed that each board of education is

expressly empowered by the legislature to locate and acquire

sites for schoolhouse or school buildings. Fourth Class, § 77;

Third Class, § 1 1 3 ; Second Class, § 1 6 5 ; and First Class, § 192

of the school code of 1 9 5 5 , supra

The legislature has expressly empowered boards of

education to hire teachers and staff (§569, §574), determine

curriculum (§ 583), control attendance of nonresident pupils

(§582), acquire transportation on title retaining contracts

(§ 594), consent to annexation of other school districts (§ 431),

to consolidate with other school districts (§ 402), and to

determine attendance areas (§ 589). These powers are conferred

by the cited sections of the school code of 1955, supra.

The M ic h ig a n Suprem e C o u r t h a s p a s s e d upon t h e p o w e r

o f a b o a r d o f e d u c a t i o n t o d e t e r m i n e a t t e n d a n c e a r e a s i n H i a r s

v D e t r o i t S u p e r i n t e n d e n t o f S c h o o l s , 376 M ich 2 2 5 ( 1 9 6 5 ) , a s u i t

b r o u g h t and d e c i d e d a f t e r t h e e f f e c t i v e d a t e o f t h e 1 9 6 3

C o n s t i t u t i o n . The C o u r t u p h e l d t h e a u t h o r i t y o f t h e D e t r o i t

B o a r d o f E d u c a t i o n t o e s t a b l i s h a t t e n d a n c e a r e a s i n t h e s c h o o l

d i s t r i c t , p a s s e d upon t h e n a t u r e o f t h e p o w e r l e g i s l a t i v e l y

-16-

conferred and ruled:

"In this case, the authority was ample

for what the school board intended.

School boards are authorized by statute

to establish attendance areas within the

school district (CLS 1961, §340.589

[Stat Ann 1959 Rev §15.3589].) A school

board is empowered to 'establish and carry

on such grades, schools and departments as

it shall deem necessary or desirable for

the maintenance and improvement of the

schools.' (CLS 1961, §340.583 [Stat Ann

1959 Rev §15.3583].) In addition, defen

dant board as a school district of the

first class is specifically empowered 'to

adopt bylaws, rules and regulations for

its own government and for the control

and government of all schools, school

property and pupils.' (CLS 1961, §340.192

[Stat Ann 1959 Rev §15.3192].) We conclude,

therefore, that defendants not only are

given broad powers by the legislature but

specific powers embracing the establishing

of schools and attendance areas within

the district...." p 235

Moreover, in Mason v Board of Education of the

School District of the City of Flint, 6 Mich App 364

(1967) and Jipping v Lansing Board of Education, 15 Mich

App 441 (1968) Leave to Appeal Denied 382 Mich 760 (1969)

Michigan's appellate courts have sustained the discretionary

power of local boards of education, as provided by statute,

-17-

to change attendance areas within the school districts

under their jurisdiction. Further, in these two Michigan

cases Michigan's appellate courts have held that, in the

exercise of such discretionary statutory authority, local

boards of education may establish or alter attendance

areas to provide increased racial balance within the

schools.

Most importantly, the power to certify and

levy taxes within the appropriate tax limitations provided

by the people in Const 1963, art 9, §6, is conferred by

§§564, 615 and 643a of the school code of 1955, supra.

Thus, it must be concluded that the legislature

has organized school districts or boards of education of

first and second class school districts as bodies corporate

with the power to sue and be sued. Even a forcibly

annexed school district has legal authority to sue to ques

tion the validity of the annexation proceedings. As bodies

corporate, school districts or boards of education have

express statutory authority to retain their own attorneys

to advise them and to represent them in all courts.

-18-

In this regard, it must be stressed that the complaint filed

by appellees herein listed the Board of Education of the City

of Detroit, organized under the laws of this state, as one of

the defendants herein. From the very first the Detroit Board

of Education has been ably represented by attorneys of their

own choosing. Certainly there should not be one rule for the

Detroit Board of Education in this regard and another rule for

the remaining 52 school districts within the desegregation area.

Further, whether designated as agencies of the state or municipal

corporations, school districts possess plenary powers as are con

ferred by the legislature to carry out the delegated functions

entrusted to them by the legislature.

B . The power of control over school districts

There is a vast body of case law issued by the Michigan

Supreme Court that subject only to the provisions of the Michigan

Constitution, the legislature has the entire control over public

schools in the state of Michigan. Attorney General, ex rel.

Zacharias v Board of Education of City of Detroit, 154 Mich 584

(1908); MacQueen v City Commission of City of Port Huron, 194

Mich 328 (1916); Common Council of the City of Detroit v Engel,

202 Mich 536 (1918); Child Welfare Society of Flint v Kennedy

School District, 220 Mich 290 (1922); Van Fleet v Pitman, 244

Mich 241 (1928); In re School District No. 6, Paris and Wyoming

Townships, Kent County, 284 Mich 132 (1938); Ira School District

No. 1 Fractional v Cnesterfieia School District No. 2

Fractional, 340 Mich 678 (1954); Sturgis v County of Allegan,

343 Mich 209 (1955); Jones v Grand Ledge Public Schools, 349

Mich 1 (1957); Board of Education of Presque Isle Township

School District No. 8 v Presque Isle County Board of Education,

357 Mich 148 (1959); Imlay Township Primary School District

No. 5 v State Board of Education, 359 Mich 478 (1960).

It must be noted that the Michigan constitutional

provisions in effect during this time were:

Const 1908, art 11, § 9:

"The legislature shall continue a system of

primary schools, whereby every school district

in the state shall provide for the education

of its pupils without charge for tuition;

II

Const 1908, art 11, § 2:

"A superintendent of public instruction shall

be elected . . . He shall have general super

vision of public instruction in the state. . .

His duties and compensation snail be orescribed

by law."

Const 1908, art 11, § 6:

"The state board of education shall consist of

four members. . . . The state board of education

shall have general supervision of the state

normal college and the state normal schools,

and the duties of said board shall be prescribed

by law."

Thus, the controlling law can be summarized by quoting

from School District of the City of Lansing v State Board of

-20-

Education, 367 Mich 591 (1962);

"Unlike the delegation of other powers by the

legislature to local governments, education is

not inherently a part of the local self

government of a municipality except insofar

as the legislature may choose to make it such.

Control of our public school system is a State

matter delegated and lodged in the State legis

lature by the Constitution. The policy of the

State has been to retain control of its school

system, to be administered throughout the

State under State laws by local State agencies

organized with plenary powers to carry out the

delegated functions given it by the legislature."

p 595

Indeed, this Court, in Bradley v Milliken, 433 F2d

897 (1970), has recognized the plenary power of the legislature

over school districts as arms and instrumentalities of the state,

including local boards of education, subject to federal consti

tutional provisions.

In 1963 tiie people revised the Michigan Constitution,

effective January 1, 1964. Provisions pertinent to this case are

"Const 1963, art 8, § 2:

"The legislature shall maintain and support a

system of free public elementary and secondary

schools as defined by law. Every school district

shall provide for the education of its pupils

without discrimination as to religion, creed,

race, color or national origin."

Const 1963, art 8, § 3:

"Leadership and general supervision over all

public education, . . . is vested in a state

board of education. It shall serve as the

general planning and coordinating body of all

public education, including higher education,

-21-

and shall advise the legislature as to the

financial requirements in connection therewith.

"The state board of education shall appoint a

superintendent of public instruction whose term

of office shall be determined by the board.

He shall be the chairman of the board without the

right to vote, and shall be responsible for the

execution of its policies. He shall be the

.principal executive officer of a state department

of education which shall have powers and duties

provided by law. . . . "

Comparing the controlling provisions of the 1908 and

1963 Michigan constitutions, cited in pertinent part above, it

is clear that under both constitutions, the power of "general

supervision" of public instruction (Const 1908, art 11, § 2)

and of "public education" (Const 1963, art 8, § 3) was vested

in the superintendent of public instruction, and is now reposed

in the state board of education. In addition, a new power of

"leadership" is vested in the State Board of Education. The role

of the legislature in maintaining and supporting a system of free

public schools "as defined by law" is virtually unchanged under

both constitutions.

The meaning and inter-relationship of Const 1963,

art 8, §§ 2 and 3 came before the Michigan Supreme Court in

Welling v Livonia Board of Education, supra. At issue in Welling

was the power of the board of education to provide half-day

instruction for its pupils because of lack of funds. Relying

upon Const 1963, art 8, § 2 and quoting the first sentence

thereof, the court unanimously held:

-22-

"The legislature has set up a system of free

public elementary and secondary schools by

enacting the provisions of the school code."

(1955 PA 269, supra.) p 623

The Court then considered the grant of power to the

State Board of Education as conferred by the people in the first

sentence of Const 1963, art 8, § 3, and held that as a part of the

responsibility of the state board of education it was empowered

to promulgate regulations to specify the number of hours to

constitute the school day. The unanimous per curiam opinion of

the Court in Welling emphasized the exercise by the State Board

of Education of its constitutional authority to specify the number

of hours of the school day through the promulgation of rules or

regulations. Promulgation of rules or regulations by the State

Board of Education must be in compliance with the provisions of

1969 PA 306, MCLA 24.201, et seq; MSA 3.560(101) et seq, which

require public inspection of proposed rules, notice of hearing

to the public, public hearing, filing with the secretary of state

and publication in the state administrative code as a minimum

to valid promulgation. The predecessor act, 1943 PA 88, also

contained comparable requirement for promulgation of rules.

In the absence of the promulgation of such a regulation, a

board of education did not abuse its discretion in providing

half-day instruction to its pupils because of lack of funds to

operate a full day. Such a holding was responsive to the issue

in tiie case and, it is emphasised, represents a unanimous

-23-

We stress the unanimous holding in Welling because

of the concurring opinion of Mr. Justice Black in Welling,

supra, joined by only two other justices and thus a minority

view of the Court, in which Mr. Justice Black held that the

overall power of the legislature over public education had been

transferred by the people to the state board of education in

Const 1963, art 8, § 3, supra. He reasoned that the powers of

the state board of education were unfettered by the limitation

of "prescribed by law" or "provided by law." It must be noted

that the decision in Welling was rendered only two days after

oral argument, possibly explaining the brevity of the two

opinions.

However, it is not difficult to understand why the

concurring opinion of Mr. Justice Black failed to receive a

majority of signatures of the Court. It is abundantly clear

that the concurring opinion of Mr. Justice Black failed to

consider the second paragraph of Const 1963, art 8, § 3,

particularly the plain intent of the people expressed therein

to create a "state department of education which shall have

powers and duties "provided by law" as well as art 5, § 2,

which requires all executive and administrative offices, agencies

and instrumentalities and their respective functions, powers and

duties to be allocated by law within 20 principal departments.

decision of the Michigan high court.

-24-

Under the mandate of 1963, art 5, § 2, the legislature

has created a department of education, designated the state

board of education as the head of the department and transferred

all of its powers, duties and functions to such department.

See 1965 PA 380, §§ 300, 301 and 302, MCLA 16.400-402? MSA

3.29(300)-29(302).

Thus, the decision in Welling stands for the following

propositions:

1. The power of the legislature to set up and organize

school districts, as provided in the school code of 1955, supra,

is undiminished.

2. The state board of education has the constitutional

authority to promulgate rules and regulations in accordance with

law to prescribe the number of hours of the school day. In the

absence of the promulgation of such a rule or regulation, and the

imposition of a clear duty upon the local board of education by the

state board of education, the local board of education did not

abuse its discretion when it provided half-day instruction to its

pupils because of lack of funds.

The decision in Welling does not stand for the proposition

that the people have transferred all the authority over public

education from the legislature to the state board of education.

Such a reading of Welling is supported by the decision

-25-

of the Michigan Court of Appeals in Schwan v Lansing Board of

Education, 27 Mich App 391 (1970), leave to appeal denied in

384 Mich 797 (1971), where the Court found broad authority in

a board of education to establish and operate nongraded school

programs in elementary schools as conferred by § 583 of the

school code of 1955, supra, the Court not being appraised of

any action by the state board of education prohibiting establish

ment of nongraded programs.

Subsequent to the decision in Welling, the Michigan

Supreme Court in Munro v Elk Rapids Schools, 383 Mich 661 (1970)

construed the Tenure of Teachers Act as it affects school districts

and their relationship with their teachers and administrators

and quoted with approval the following language from Rehberg v

Board of Education of MeIvindale, Ecorse Township School District

No. 11, Wayne County, 330 Mich 541, 548 (1951):

"School districts, though state agencies, are

governed locally and their controlling boards

are chosen by the electorate. (See PA 1927,

No. 319 [CL 1948, § 341.1 et seq. (Stat Ann

§15.1 et seq.)].) If the legislature intended

to deprive local governing bodies of adminis

trative control of teachers, that intent should

have been definitely stated in the tenure act."

(p 674)

On rehearing, the majority reversed and ruled that the legislature

had indeed placed such limitation upon school districts. 385 Mich

618 (1971). Thus Munro holds that the legislature has the power

to place limitations upon school districts in their relationships

-26-

with teachers and other educational personnel. Further, the

authority of the legislature to proscribe the strike of or with

holding of services of public school teachers from Michigan

school districts was upheld in School District for the City

of Holland v Holland Education Association, 380 Mich 314 (1968),

even though the Court disagreed under what circumstances

injunctive relief would be granted to prevent teachers not

under contract with the school district to withhold their

services.

The Attorney General has ruled that the State Board

of Education has constitutional and statutory rule-making power

for procedural safeguards in the suspension or expulsion of

pupils. OAG 1969-70, p 156.

". . . The State Legislature has not required

the STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION to act in this

area, either by a grant of power to suspend or

expel, or by a mandatory requirement to offer

an appeal procedure. An opinion of the Attorney

General of the State of Michigan that the STATE

BOARD has discretionary powers adds nothing to

the statute."

Slip Opinion of Judge Cornelia Kennedy in Claus

v State Board of Education, et al, U.S. District

Court, ED Mich SD, decided on July 12, 1972.

The Attorney General has also ruled that the State Board of

Education has constitutional authority to establish a program

for the accrediting of Michigan public schools but is under no

constitutional duty to do so. OAG No. 4707, dated May 5, 1971.

-27-

Under these decisions of the Michigan Supreme

Court and the Court of Appeals, it must be concluded that

the power of the legislature to set up and organize school

districts, and to prescribe their powers and duties is

undiminishea. Welling v Livonia Board of Education, supra,

Senghas v L'Arise Creuse School District, supra.

Tnere is a suggestion by the District Court in

tire latter portion of paragraph 13 of the Conclusions of

Law in the Ruling on Segregation (la 213-214) that the State

Board of Education possesses plenary power over school

districts because it may ratify, reject, amend or modify

actions of school districts under certain cited statutes.

Even a cursory examination of such statutes reveals that the

District Court's inferences are unwarranted.

MCLA 340.442; MSA 15.3442, authorizes the State

Board of Education to review the annexation or attachment

of a closed school district not operating any schools for

any two year period but only if one or all of the affected

districts specifically request such review.

MCLA 340.467; MSA 15.3467, confers authority upon

the State Board of Education to review requests for the

transfer of territory between school districts and to confirm,

modify or set aside orders of intermediate boards of education,

-28-

but only if requested by appeal of one or more resident

owners of lana considered for transfer or by the board of

any district that is affected by the proposed transfer.

Reference was also made to MSA 15.1919(61), which imposes

a statutory duty only upon the superintendent of public

instruction to review bus routes.

MCLA 388.628(a); MSA 15.1919(68b) provides for addi

tional state aid allotments to school districts that had been

reorganized and imposes only ministerial duties upon the

superintendent of public instruction. These provisions have

been repealed by 1972 PA 258, § 179. (ixa 640)

MCLA 388.681 et seq; MSA 15.2299(1) et seq, provides

- - . . antor the reorganization of school districts by/intermediate

district committee for the reorganization of school districts

Neither the state board of education nor the superintendent

of public instruction has any authority under this act. It

is noted that the act expired on the filing of a final report

of the state commission on or before September 1, 1968. The

authority of the superintendent of public instruction over

the construction of school buildings, as set forth in 1937

PA 306, Sec. 1, MCLA 388.851; MSA 15.1961, is discussed infra

-29-

There is no authority in this act to ratify, reject,

amend or modify the action of inferior state agencies.

The District Court also cites MCLA 340.402; MSA

15.3402. This section authorizes the superintendent of

public instruction to approve or deny a proposal to

initiate proceedings to effect a proposed consolidation,

but no consolidation can take effect without the approval

of the electors as set forth in MCLA 340.409; MSA 15.3409.

Finally, the District Court relied upon MCLA

388.717 et seq; MSA 15.2299(57). The limited authority

of the state board of education to reorganize a district,

if an emergency warrants such reorganization, exists solely

by file autnority conferred by the legislature. Airport

Community Schools v State Board of Education, 17 Mich

574 (1969).

Thus, it must follow that the suggestion of plenary

authority is totally unwarranted since the legislature, in

specified grants of authority, has imposed certain duties

upon the state board of education and superintendent of

public instruction to be exercised within the limits specified

by the legislature.

-30-

Clearly, the legislature has the authority to:

(1) alter school dxstrict boundaries, Penn School District

N o . 7 v Lewis Cass Intermediate School District Board of

Education, 14 Mich App 109, 120 (1968); (2) appropriate

money for the support of public school districts, Mich

Const 1963, art 8, § 2 and art 9, § 11; (3) establish

schools and attendance areas, Iiiers v Detroit Superintendent

of Schools, supra; (4) govern the relationships of school

districts and their teachers and other educational personnel,

Munro v Elk Rapids Schools, supra, and (5) control the

labor relationships of the school district and its teachers

as well as to prohibit strikes by teachers, School District

for City of Holland v Holland Education Association, supra.

The decided Michigan cases hold that in accorcance

with rules and regulations promulgated under the provisions

of 1969 PA 306, supra, the state board of education has consti

tutional authority to prescribe the length of the school day, Welling

v Livonia Board of Education, supra, and arguably to prohibit the

-31-

establishment of ungraded programs in elementary schools.

Schwan v Lansing Board of Education, supra. Until the State

Board of Education promulgates such rules and regulations,

boards of education do not abuse their discretion when they,

under broad authority conferred by the legislature, offer

half-day programs to their pupils for lack of funds or when

they establish nongraded programs in elementary schools.

There is no appellate decision of a Michigan court extending

the constitutional authority of the State Board of Education

beyond these limits.

Moreover, the Michigan Supreme Court in Jones v

1 ~

Grand Ledge Public Schools, 349 Mich 1 (1957), has clearly

recognized school districts as independent governmental

agencies, separate and distinct from other municipal

corporations and separate and distinct from other school

districts so that the Grand Ledge Board of Education was not

required to educate pupils residing in other school districts.

School districts are distinct governmental agencies independent

of townships, cities and counties in which they may be located.

Board of Education v City of Detroit, 30 Mich 505 (1875).

Thus, in Michigan, school districts are governmental entities

independent of other governmental entities, including other

school districts. See dissenting opinion of Mr. Chief Justice

lrPhis case is consistent with Const 1963, art 8, § 2 which

requires every school district to “provide for the education

Cj- ^ -s, pupirs without discrimination." [Emphasis supplied]

-32-

Burger, Wright v Council of City of Emporia, ___ US ___;

92 S Ct 2196, 2211 (1972), also cited herein as 40 US LW 4806,

(US, June 20, 1972)

In all candor these appellants must inform this

Court that the State Board of Education does not possess

constitutional authority to organize school districts, to

designate the legal status of school districts or their

boards of education as bodies corporate with power to sue or

to be sued, to determine what attorneys shall represent them,

to alter school district boundaries, to appropriate money for

the support of school districts, Michigan Education Association,

et al v State Board of Education, Michigan Court of Appeals

No. 11,900, decided and order issued July 8, 1971, to establish

schools and determine attendance areas, to govern the relation

ships of school districts and their teachers and other educational

personnel, and to control labor relations of school districts

and its teachers, as well as to prohibit strikes by teachers,

under the decisions of the Michigan Supreme Court and Court

of Appeals cited herein. The people have reposed these

powers in the Michigan legislature under the Constitution

of 1963.

-33-

II.

BASED ON THE RECORD IN THIS CASE, THE DISTRICT

COURT’S FINDINGS OF FACT AND CONCLUSIONS OF

LAW OF DE JURE SEGREGATION IN THE PUBLIC SCHOOLS

OF THE DETROIT SCHOOL DISTRICT IS ERRONEOUS_____

Michigan, unlike some other states, has a strong legal

tradition of prohibiting, by positive law, de jure dual school

systems. In The People, ex rel Workman v Board of Education of

Detroit, 18 Mich 399, 408-409 (1869), the Michigan Supreme Court

held, based on statutory enactments of the legislature, that the

Detroit Board of Education could not lawfully maintain separate

schools for black and white children. In doing so, the Court re

cognized, at p. 412, that the Detroit Board of Education could

lawfully establish geographical attendance areas for its schools,

provided all children within each attendance area have an equal

right to attend school irrespective of race. It must be observed

that this decision, which is still the law in Michigan, was handed

down 27 years before the United States Supreme Court enunciated the

pernicious doctrine of separate but equal in Plessy v Ferguson,

163 US 537 (1896), and 85 years before Brown v Board of Education,

347 US 483 (1954).

Section 355 of 1955 PA 269, as amended, supra, provides:

"No separate school or department shall be kept

for any person or persons on account of race or

color..."

In Const 1963, art 8, §2, the people of the State of

Michigan have provided:

-34-

"The legislature shall maintain and support a

system of free public elementary and secondary

schools as defined by law. Every school district

shall provide for the education of its pupils

without discrimination as to religion, creed,

race, color or national origin."

The Address to the People accompanying this constitutional

provision provides, in pertinent part, as follows:

"The anti-discrimination clause is placed in

this section as a declaration which leaves no

doubt as to where Michigan stands on this

question."

Thus, it is beyond dispute that Michigan is not a de jure

state with a dual school system mandated by state law.

Moreover, it must be emphasized that some Michigan school

boards in large city school districts have altered school attendance

areas to achieve racial balance although there is no constitutional

duty to achieve racial balance. See Mason v Board of Education

g l ._the School District of the City of Flint, 6 Mich App 364

; -lipping v Lansing Board of Education, 15 Mich App 441 (1968);

leave to appeal denied 382 Mich 760 (1969); and Swann v Charlotte-

Meek lenburg Board of Education, 402 US 1, 15-18, (1971). These

two Michigan cases negative any suggestion that Michigan is, in

the operation of its school districts, a de jure state with a dual

school system.

Thus, the question of whether the Detroit public schools are

de jure segregated must be answered by reference to the conduct of

-35-

the original defendants relating to the operation of such schools.

These defendants v/ould strongly emphasize that the district court

erred in finding de jure segregation in the Detroit public schools.

The lower court obliterated the firm legal distinction between

de jure segregation by school authorities (Brown v Board of Educa

tion , supra) and racial imbalance in the public schools as a result

of housing patterns which school authorities have no affirmative

duty to overcome. Spencer v Kugler, 326 F Supp 1235, 1242-1243

(DC NJ, 1971) affirmed on appeal 404 US 1027 (1972).

This contention is vividly illustrated by the following

language from the "Ruling on Issue of Segregation" as follows:

. . As we assay the principles essential to

a finding of de jure segregation, as outlined in

rulings of the United States Supreme Court, they

are:

1. The State, through its offices and agencies,

and usually, the school administration, must have

taken some action or actions with a purpose of

segregation. 2 3

2. This action or these actions must have

created or aggravated segregation in the schools

in question.

3. A current condition of segregation exists.

"We find these tests to have been met in this case.

We recognize that causation in the case before us

is both several and comparative. The principal

causes undeniably have been population movement

and housing patterns, but state and local governmental

actions, including school board actions, have played

a substantial role in promoting segregation. It is,

the Court believes, unfortunate that we cannot deal

-36-

with public school segregation on a no-fault basis,

for if racial segregation in our public schools is

an evil, then it should make no difference whether

we classify it de jure or de facto. Our objective,

logically, Tt seems to us” iHouldbe to remedy a

condition which we believe needs correction. In

the most realistic sense, if fault or blame must

be found it is that of the community as a whole,

including, of course, the black components. We

need not minimize the effect of the actions of

loaning~Tnstitutions and real estate firms, in

fe5ira~XT~ state and"ToeaT.gbvernmental.officers

and agencies, and the actions".ofT the e s t ab11 "sfiment

and maintenance of segregated resl^entlaX'laabterni' -

which lead to schooT~~segregatibn . . T 11

(Emphasis supplied). ("l a 194, 210-211}

These defendants agree with the three principles enunciated

by the lower court as essential to a finding of de ;jure segregation,

with the caveat that the first principle must be limited to the

actions of school authorities. Swann v Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Board of Education, 22-23, supra. However, these defendants *

respectfully submit that the lower court's opinion is not consistent